Abstract

A range of risk factors lead to opioid use and substance-related problems (SRP) including childhood maltreatment, elevated impulsivity, and psychopathology. These constructs are highly interrelated such that childhood maltreatment is associated with elevated impulsivity and traumarelated psychopathology such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and impulsivity—particularly urgency—and PTSD are related. Prior work has examined the association between these constructs and substance-related problems independently and it is unclear how these multifaceted constructs (i.e., maltreatment types and positive and negative urgency) are associated with one another and SRP. The current study used structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the relations among childhood maltreatment, trait urgency, PTSD symptoms, and SRP in a sample of individuals with a history of opioid use. An initial model that included paths from each type of childhood maltreatment, positive and negative urgency, PTSD and SRP did not fit the data well. A pruned model with excellent fit was identified that suggested emotional abuse, positive urgency, and negative urgency were directly related to PTSD symptoms and only PTSD symptoms were directly related to SRP. Furthermore, significant indirect effects suggested that emotional abuse and negative urgency were related to SRP via PTSD symptom severity. These results suggest that PTSD plays an important role in the severity of SRP.

Keywords: PTSD, opioid addiction, childhood maltreatment

1. Introduction

Opioid use and misuse is a serious public health problem that is associated with chronic infectious disease (e.g., hepatitis B and C, HIV), high mortality rates, and significant functional impairment (Volkow et al., 2014). People who use opioids, including misusing prescription opioids and heroin, often report extensive histories of childhood maltreatment (Daigre et al., 2015; Kessler et al., 2010). The severity of such maltreatment is correlated to the severity of substance use broadly and substance use related problems (SRP) specifically (Conroy et al., 2009; Heffernan et al., 2000). SRP are defined as emotional, physical, financial, and biological impairment that are attributed to the use of substances, which are substantial for those who use opioids (Kiluk et al., 2013). For example, increased guilt, shame, and decrements to one’s physical health because of opioid use are considered SRP. Not all adults who were victimized as children, however, use opioids or experience SRP. This variability suggests that there are important intermediary factors that influence how maltreatment affects later opioid use and problems (Hovdestad et al., 2011). Understanding such pathways are necessary to improve prevention and treatment efforts for problematic opioid use.

Childhood maltreatment refers to the range of abuse and neglect children experience from caregivers, including emotional abuse, emotional neglect, physical abuse, physical neglect, and sexual abuse. Although there is considerable co-occurrence of abuse types, there is evidence that each confers unique risk for future maladaptive outcomes, such as substance use (Senn and Carey, 2010). For example, the type of abuse experienced was associated with the type of substance used and the severity of impairment in a sample of adults with substance use disorder (Tonmyr et al., 2010). Few studies, however, have examined how different types of childhood maltreatment are associated with SRP among those who use opioids. Instead, the majority of studies have either treated maltreatment as a unidimensional construct—ignoring the potential differences between maltreatment types—or focused on a single maltreatment type (Clemmons et al., 2007; De Bellis, 2002; Higgins, 2004; Higgins and McCabe, 2001; Simpson and Miller, 2002). It therefore remains unclear if and how specific types of childhood maltreatment are related to SRP.

A proposed pathway by which early traumatic experiences, such as childhood maltreatment, leads to substance use problems (e.g., SRP) is via trait impulsivity (Beauchaine and Gatzke-Kopp, 2012). That is, exposure to child maltreatment may contribute to systematic patterns of rash behavior that increase risk for opioid use and SRP. Impulsivity is not unitary, however, and a growing evidence supports the presence of multiple impulsivity-related traits (e.g., Depue and Collins, 1999; Sharma et al., 2014; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). A prominent model (Whiteside and Lynam, 2001) describes impulsivity-related traits including negative urgency (rash action under conditions of negative affect), lack of premeditation (acting without forethought or consideration of consequences), lack of perseverance (difficulty persisting on boring or challenging tasks), sensation seeking (pursuit of novel, exciting experiences even when dangerous), and positive urgency (rash action under conditions of positive affect). The literature on how these impulsivity traits are related to opioid use and SRP lags behind the study of other substances (Mitchell and Potenza, 2014; Verdejo-García et al., 2007), partly due to including opioid use as part of generic “substance use” or “illicit drug use” measures rather than as a specific outcome. Prior work has indicated that positive and negative urgency may be most relevant to psychopathology and substance use (Peters et al., 2012; Weiss et al., 2015). Others have suggested that urgency may be more strongly related to SRP than other impulsivity-related constructs. In two studies where impulsivity was measured via performance on behavioral tasks, those with a history of opioid use performed more poorly on tasks involving affect-related decision making relative to controls (Baldacchino et al., 2015; Passetti et al., 2008). There were no other notable differences on measures of impulsivity between these groups. These data suggest that SRP may be more closely tied to urgency than other facets of impulsivity.

Childhood maltreatment and urgency are also associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Contractor et al., 2016). It is proposed that an inability to cope with the strong negative emotions that results from childhood maltreatment markedly increases risk for PTSD. In an effort to cope with PTSD symptoms and these other risk factors, the individual may turn to using substances (Weiss et al., 2013). Indeed, estimates of the comorbidity between PTSD and those with a history of substance use disorder for opioids is as high as 62% (Dore et al., 2012; Mills et al., 2006). Furthermore, PTSD is associated with more severe substance-related impairment and poorer response to substance use disorder treatment (Mills et al., 2007; Weiss et al., 2015).

Taken together, the current literature supports relations between childhood maltreatment, urgency, PTSD, and SRP. There are important nuances to these relations, however. The type of maltreatment experienced may be relevant to impulsivity severity, PTSD symptom severity, and SRP. Furthermore, there are likely indirect effects among these variables (e.g., the effect of childhood maltreatment types on SRP via urgency). Yet it is unclear as to how these associations manifest. Structural equation modeling (SEM) can evaluate this set of relations in that multiple paths can be tested simultaneously and variables can serve as both outcomes and predictors within the same model.

The present study used SEM to examine the relation between types of childhood maltreatment, types of urgency, PTSD, and SRP in those who have used opioids. The initial model hypothesized that all types of childhood maltreatment would be associated with impairments in positive and negative urgency and PTSD. Furthermore, both types of urgency would be associated with PTSD and SRP. Finally, PTSD was hypothesized to be related to SRP.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were 84 individuals with a history of opioid use, defined as having used heroin or misused prescription opioids for > 1 year (Heroin: M = 4.87 years, SD = 5.87; Prescription opioids: M = 6.98 years, SD = 6.02), met lifetime DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse: opioid, and identified opioids as their substance of choice. The majority of participants used opioids in the past month (n = 62, 73.8%), excluding use related to a treatment program. A portion of the sample 28.6% (n = 24) was currently enrolled in methadone maintenance treatment (MMT). Exclusion criteria included active psychosis and non-English speaking. Participants were included if they used other substances. Historical use of substances (in years of regular use) were as follows: Alcohol: M = 5.64, SD = 7.90; Cocaine: M = 5.01, SD = 7.20; Cannabis: M = 10.98, SD = 11.83.

Participants were M = 35.27, SD = 8.26 years old. The majority were male (n = 45, 53.6%). The majority of the sample was at or below the federal poverty level, earning less than $10,000 per year (n = 46, 54.8%). The sample was representative of Northern New England in that the majority self-identified as White (n = 72, 85.7%). The remaining participants selfidentified as African-American (n = 2, 2.4%), Asian American (n = 2, 2.4%), Native American (n = 4, 4.8%), Bi-Racial (n = 2, 2.4%), and “Other-group” (n = 2, 2.4%). Two participants (2.4%) self-identified as Latino. Participants were recruited from the community through a series of targeted internet advertisements (e.g., Craigslist and Facebook) and through flyers posted in local businesses.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ: Bernstein and Fink, 1998)

The CTQ is a 28-item self-report scale that assesses five categories of negative childhood experiences: emotional neglect, emotional abuse, physical neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. Each item is assessed on 1 to 5 scale with subscale scores ranging from 5–25 with higher scores indicating greater abuse. Internal consistency for the subscales was excellent, ranging from α = .80 to .96.

2.2.2 Short Inventory of Problems-Revised (SIPS-R; Kiluk et al., 2013)

The SIPS-R is a 17-item measure of the negative consequences of drug use or drinking. The current study specified that the SIPS-R is associated with currents problems related to substances, which are defined as those experienced in the last three months. Items are rated on a scale from 0=never to 3=daily or almost daily, with total scores ranging from 0 to 51. Higher scores indicate greater impairment due to substances. Examples of problems include feeling guilt or shame when using substances, having their physical health harmed by using substances, or having their social life negatively affected by using substances. Internal consistency for the total scale was excellent, α = .98.

2.2.3 Addiction Severity Index Lite (ASI-Lite; McLellan et al., 1997)

The ASI-Lite is 169-item structured interview that was adapted from the ASI-5. It is a shorter alternative to the ASI-5. It assesses the severity of an individual’s drug or alcohol addiction as well as different domains that may be impacted (McLellan et al., 1992). The ASI-Lite determined the frequency of the substance use for each participant.

2.2.4 Short Form of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (SUPPS-P; Cyders et al., 2014)

The SUPPS-P is a 20-item self-report questionnaire derived from the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006). Items are rated on a 1–4 scale with higher scores indicating less impulsivity. The negative urgency and positive urgency scales were used for the current study. Internal consistency for the scales were adequate, Negative Urgency α = .77; Positive Urgency α = .65.

2.2.5 PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure of severity of current PTSD symptoms in the past month. The total score for the PCL-5 ranges from 0 to 80 with items scored on a 1–5 scale. Higher scores represent more severe PTSD symptoms. Internal consistency was excellent, α = .96.

2.2.6 Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-5 Disorders (SCID; First et al., 2015)

The SCID-5 is a semistructured interview used to diagnosis psychopathology according to DSM-5 criteria. For the current study, the SCID-5 was used to determine if an individual met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD.

2.2.7 MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV (MINI; Sheehan et al., 1998)

The MINI is a semistructured interview used to evaluate the presence of mental health disorders. The current study used the non-alcohol psychoactive substance use disorder section to determine eligibility for the study. Specifically, the four questions pertaining to substance abuse were asked of participants to determine if they met criteria for substance abuse according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV criteria in their lifetime.

2.3 Data Analytic Plan

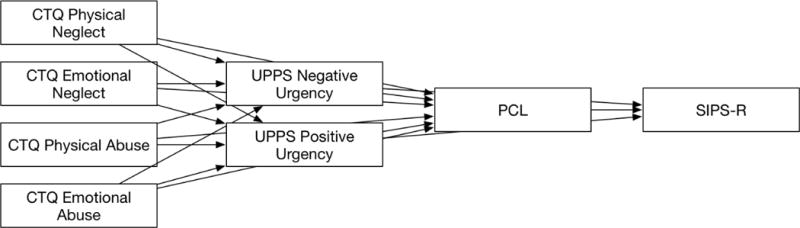

Bivariate correlations were conducted to determine the strength of the relation among all variables. Data were fitted to an initial path model that included paths for the following: all CTQ scales to the urgency scales; all CTQ scales to the PCL-5; urgency scales to the PCL-5; all urgency scales to the SIPS-R; and PCL-5 to the SIPS-R (Figure 1). Fit was evaluated using the guidelines specified by (Hu and Bentler, 1999). Specifically, a well-fitting model is defined as: a non-significant chi-square difference test, RMSEA < .08, CFI > 0.95, and SRMR < .08. After an initial model was fitted, a pruning strategy was used in which paths were removed. First, nonsignificant paths from the CTQ scales to PCL-5 were removed. Second, non-significant paths from the CTQ scales to the urgency scales were removed. Third, the paths from the urgency scales to the PCL-5, and SIPS-R were removed. Fit for nested models was evaluated with a chi-square difference test. Fit for non-nested models was evaluated with the difference in BIC, with the lower value having better fit.

Figure 1.

Initial model evaluating childhood trauma exposure, impulsivity sub-types, PTSD symptoms and substance-related problems. Fit statistics were: χ2 (2) = 12.09, p = .002; RMSEA = 0.25, 95% CI [0.13 to 0.393]; CFI = 0.87; SRMR = 0.06; BIC = 2217.88.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics suggested that the sample reported overall moderate PTSD symptoms with (M = 37.53, SD = 19.45) and moderate exposure to childhood maltreatment (Table 1). The majority of the sample met criteria for current PTSD (n = 57, 67.9%) according to the SCID-5. Those who met criteria for PTSD had significantly higher PCL-5 scores (M = 46.21, SD = 14.85) than those who did not meet criteria for PTSD (M = 21.18, SD = 15.09), F (1, 82) = 51.55, p < .001. Bivariate correlations between the variables of interest suggested that the PCL-5 was significantly related to all CTQ scales, Positive Urgency, Negative Urgency, and the SIPS-R (Table 1). The SIPS-R was associated with Positive Urgency, Negative Urgency, and PCL-5, however. Preliminary comparisons indicated there were no significant differences between those in MMT and those not in MMT across all measures (p’s = .208 to .986).

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations of all variables in the model.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| 1. PCL-5 Total | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. CTQ Physical neglect | .25* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. CTQ Emotional neglect | .23* | .65** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. CTQ Sexual abuse | .31** | .26* | .29** | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. CTQ Physical abuse | .38** | .44** | .49** | .43** | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. CTQ Emotional abuse | .42** | .56** | .74** | 4.2** | .69** | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Negative urgency | − .44** | .01 | −.13 | −.07 | −005 | −.14 | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Positive urgency | −.22* | .10 | −.07 | −.01 | .01 | −.05 | .52** | 1.00 | |

| 9. SIPS Total | .49** | .06 | −.02 | .03 | .05 | .17 | −.34** | −.29** | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||||

| Mean | 37.53 | 10.44 | 14.00 | 10.67 | 10.71 | 12.26 | 8.97 | 11.62 | 20.72 |

| SD | 19.45 | 4.39 | 5.70 | 1.16 | 5.76 | 5.52 | 2.93 | 5.53 | 17.73 |

Note:

= p < 0.05.

= p < 0.01. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. SIPS-R = Short Inventory of Problems - Revised.

An initial model was fitted to the data that proposed the CTQ scales were associated with the urgency scales and PCL-5. Direct paths from the urgency scales to the SIPS-R and PCL-5 were included (Figure 1). This model demonstrated poor fit, χ2 (2) = 12.09, p = .002; RMSEA = 0.25, 95% CI [0.13 to 0.393]; CFI = 0.87; SRMR = 0.06; BIC = 2217.88. The model was then pruned by removing non-significant paths. First, non-significant paths from CTQ scales to the PCL-5 were removed. Second, non-significant paths from the CTQ scales to the urgency scales were removed. Third, the relations among the urgency scales, PCL-5, and SIPS-R were removed.

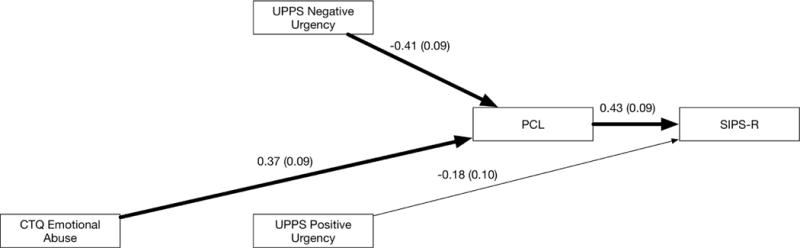

The previously described steps yielded a model that fit the data well (Figure 2); χ2 (5) = 2.12, p =0.83; RMSEA < 0.01, 95% CI [<0.01 to 0.09]; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.04; BIC = 2143.38. A chi-square difference test suggested that this model was a significant improvement in fit, χ2 (6) = 35.37, p < .001. The reduction in BIC scores was greater than 10, which suggests “very strong” evidence that this model is a better fit than the higher BIC model (Rafferty, 1995). This model accounted for 25% of the variance in drug-related problems, R2 = 0.25, p = .002. The final model retained CTQ-emotional abuse, but supported the removal of other the other CTQ scales. This model suggested that CTQ-emotional abuse (β = 0.37, p < .001) and negative urgency (β = −0.41, p < .001) were related to the PCL-5. Only the PCL-5 had a significant direct effect on the SIPS-R (β = 0.43, p < .001). The association between positive urgency and SIPS-R approached significance (β = −0.18, p = 0.071). Removing this relation from the model significantly reduced fit, which suggests it was meaningful towards the overall model.

Figure 2.

Final model of childhood trauma, impulsivity, PTSD, and substance-related problems. All paths shown are standardized estimates. Bolded lines are significant at the p < .01. Unbolded lines are not significant. Values in parentheses are standard errors. Fit statistics were: χ2 (5) = 2.12, p =0.83; RMSEA < 0.01, 95% CI [<0.01 to 0.09]; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.04; BIC = 2143.38.

An alternative model was evaluated in which the position of the SIPS-R and PCL-5 were switched to determine if SRP led to elevated PTSD symptoms. This model demonstrated poor overall fit and worse fit than the previous model: χ2 (5) = 26.41, p < .01; RMSEA = 0.23, 95% CI [0.15to 0.32]; CFI = 0.58; SRMR = 0.11; BIC = 2167.67. Therefore, the data suggest that PTSD symptom severity is indicative of SRP rather than the reverse.

The indirect effects of CTQ-emotional abuse, positive urgency, and negative urgency on SIPS-R were evaluated (Table 2). There was a significant indirect effect of CTQ-emotional abuse on SIPS-R via the PCL-5 (β = 0.16, p = 0.002, 95% CI [0.06, 0.27]). This indirect effect suggested elevated emotional abuse increased SRP via PTSD symptoms. Additionally, there was a significant indirect effect of negative urgency on SIPS-R via the PCL-5 (β = −0.18, p = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.07]). That is, elevated negative urgency was associated with SRP via elevated PTSD symptoms.

Table 2.

Indirect effects obtained in final model.

| 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Indirect Effect | Standardized Coefficient |

Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

| Positive urgency → PCL-5 | −0.04 | −0.10 | 0.01 |

| CTQ-Emotional abuse → PCL-5 | 0.13** | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| Negative urgency → PCL-5 | −0.19** | −0.30 | −0.09 |

Note:

= p < 0.01;

= p < .01. PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist. CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. SIPS-R = Short Inventory of Problems - Revised.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study provided a framework for understanding how childhood maltreatment is associated with SRP among those who used opioids. There was statistical evidence to suggest that emotional abuse and negative urgency exacerbate PTSD symptoms, which in turn increases SRP. Additional experimental research is needed, however, to confirm this pathway. There was evidence to suggest that positive urgency may have an important role in this model, but this path did not attain statistical significance. These results suggest that the effect of positive urgency on SRP may be relatively small. Interestingly, other types of maltreatment did not significantly contribute to this model. This suggests that emotional abuse may be the most relevant form of abuse with regards to SRP. This is not to say that other forms of maltreatment are not relevant to SRP, but that their contribution is smaller such that their effects were not detected in the current study. A replication of the current model in a larger sample is needed to determine the contribution of other types of maltreatment. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of PTSD symptoms and urgency in those with a history of opioid use.

The results of the present study are consistent with the differential effects model of childhood maltreatment (Senn and Carey, 2010). The differential effects model suggests that specific types of abuse are more closely associated with specific outcomes. The results of the present study suggested that emotional abuse was more closely related to SRP than any other type of abuse. There are several explanations for this finding. Burns and colleagues (Burns et al., 2010) propose that chronic emotional abuse during childhood can limit an individual’s ability to regulate emotions. Avoidance is a commonly used strategy in adults with significant childhood emotional abuse to protect themselves from strong emotions (Reddy et al., 2006). Consistent with this rationale, the current study suggests that those who experienced greater childhood emotional abuse experience more severe PTSD symptoms, which includes avoidance of trauma cues and reminders, and that this could drive SRP.

The impulsivity components of negative urgency and positive urgency contributed to the overall model. The present study suggested that negative urgency exacerbates PTSD symptoms, which further exacerbates SRP. PTSD is proposed to reflect a deficit in inhibiting reactions towards fearful stimuli (Norrholm et al., 2011). This deficit in inhibition towards fearful stimuli may be magnified by negative urgency. Prior work has also shown that deficits in emotional regulation during negative experiences increase motivation to use substances (Barahmand et al., 2016) and SRP for other substances (Verdejo-García et al., 2007). The support for this pathway in the current study further highlights the important role of PTSD symptoms in substance-related difficulties.

The results of the study have implications for clinical assessment and practice. It may be beneficial to help those in treatment learn to recognize the role that negative urgency plays in their SRP. Specifically, that they are prone to engage in rash behavior when they are distressed and that this rash behavior, which, may involve the use of opioids, contributes to other problems such as emotional, social, and health-related difficulties. The presence of these SRP may then exacerbate their negative mood, which perpetuates a cycle of use, psychopathology, and impairment. The current model suggested that PTSD is a critical variable in the severity of SRP in those with a childhood maltreatment history. Providing comprehensive interventions that address both substance use, PTSD symptoms, and improved emotion regulation strategies may prove beneficial. Although such treatments exist (Mills et al., 2004), there is need for dissemination given the high rate of trauma exposure among those who regularly use opioids (McCauley et al., 2014).

The current study had several limitations of note. First, all of the constructs in the current study were assessed via self-report, although substance use history and PTSD diagnoses were assessed with clinical interviews. Self-report measures are prone to bias and that may have affected the strength of the reported relations. The model supported in the current study should be replicated in studies that use behavioral measures of these constructs. Furthermore, the study focused on substance-related problems given that participants had an extensive history of using multiple substances despite endorsing opioids as their substance of choice. Thus, it is difficult to tease apart specific problems that are directly related to the use of opioids. Subsequent work is needed to determine to the extent to which certain problems are tied specifically to opioid use as opposed to the use of other substances or poly-substance use. Second, these results were obtained from a cross-sectional study such that the directionality of the relations can only be inferred via model fit. Longitudinal and experimental studies are needed to further evaluate the indirect relations that were proposed in the current study (MacKinnon et al., 2007). The current study also included a range of opioid users including those who have misused prescription medication, were prescribed opioids via a treatment program, and used illegal opioids such as heroin. Despite participants having extensive histories of opioid use, the nature of the identified relations may vary among type of opioid used, presence of addiction, frequency of use, and other descriptive variables. Future work should quantify the severity of a substance use disorder using the most recent diagnostic criteria. A portion of the current sample was involved in MMT, which may have affected their responses in the current study. No significant differences on demographic or key study variables – including SRP – were found between participants currently enrolled in an MMT program and those not in such a program. Further work should determine whether MMT mitigates the role of early child maltreatment, mental health symptoms, and trait impulsivity on substance-related problems. The sample size of the current study was modest relative to the number of paths tested in the model. The current study was unable to examine the potential moderating role of gender on the relations reported, which is important given the role gender plays in PTSD severity (Stein et al., 2000). There may be an important alteration in this set of relations between males and females that would inform our understanding of SRP and guide treatment. Finally, a majority of the sample was classified as living in poverty, which itself carries substantial risk for maladaptive behavior. For example, participants may have engaged in impulsive or risky behavior to address a relevant financial need. The findings of the current model may not generalize to those with greater economic means.

The current study contributed to knowledge of how childhood maltreatment, trait-impulsivity and PTSD contribute to SRP. Results suggest that PTSD explains, in part, how abuse suffered as a child is associated with SRP as an adult. It is suggested that impulsivity in the context of negative emotions may be more related to impairment than other forms of impulsivity. These findings highlight the importance of assessing the trauma history and PTSD symptom severity of those with problematic opioid use to better understand the factors that may contribute to substance-related impairment. Furthermore, it contributes to the growing call for the treatment of co-occurring psychopathology as a way to address substance use disorders (Mills et al., 2006).

Highlights.

Emotional abuse, negative urgency, positive urgency and PTSD were indicators of ORP.

Other types of abuse were not related to PTSD or ORP in the model.

PTSD was the only variable to have a significant direct relation to ORP.

Negative urgency and emotional abuse had significant indirect paths to ORP via PTSD.

Acknowledgments

Rebecca Mirhashem was supported by the University of Vermont Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship. Matthew Price, Katherine van Stolk-Cooke, and Alison Legrand were supported by 1K08MH107661-01A1 (PI: Price). Zachary Adams was supported by K23DA038257 (PI: Adams). This research was supported by a University of Vermont College of Arts & Sciences Small Grant Research Award (PI: Price). The authors would like to acknowledge Ryan Payne, Bethany Harris, and Robert Motley for their contribution to this project.

Role of Funding Source:

Nothing Declared

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Disclosures

The views expressed in the article are that of the authors and do not necessarily reflect that of the funding agencies.

Contributors:

Each author contributed to the manuscript. Rebecca Mirhashem conceptualized the study and was involved in the writing. Holley Allen, Zachary Adams, Katherin van Stolk-Cooke, Alison Legrand, and Matthew Price were involved in the writing of the study. Matthew Price obtained the funding that allowed the study to be conducted.

Conflict of Interest:

No conflict declared.

References

- Baldacchino A, Balfour DJK, Matthews K. Impulsivity and opioid drugs: differential effects of heroin, methadone and prescribed analgesic medication. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1167–1179. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barahmand U, Khazaee A, Hashjin GS. Emotion Dysregulation Mediates Between Childhood Emotional Abuse and Motives for Substance Use. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Gatzke-Kopp LM. Instantiating the multiple levels of analysis perspective in a program of study on externalizing behavior. Dev Psychopathol. 2012;24:1003–1018. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender RE, Griffin ML, Gallop RJ, Weiss RD. Assessing Negative Consequences in Patients with Substance Use and Bipolar Disorders: Psychometric Properties of the Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) Am J Addict. 2007;16:503–509. doi: 10.1080/10550490701641058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahuvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an Adolescent Psychiatric Population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Fink. Manual for the childhood trauma questionnaire. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Burns EE, Jackson JL, Harding HG. Child Maltreatment, Emotion Regulation, and Posttraumatic Stress: The Impact of Emotional Abuse. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2010;19:801–819. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2010.522947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreat. 2007;12:172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy E, Degenhardt L, Mattick RP, Nelson EC. Child maltreatment as a risk factor for opioid dependence: Comparison of family characteristics and type and severity of child maltreatment with a matched control group. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor AA, Armour C, Forbes D, Elhai JD. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder’s Underlying Dimensions and Their Relation With Impulsivity Facets: J. Nerv. Ment Dis. 2016;204:20–25. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Littlefield AK, Coffey S, Karyadi KA. Examination of a short English version of the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1372–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daigre C, Rodríguez-Cintas L, Tarifa N, Rodríguez-Martos L, Grau-López L, Berenguer M, Casas M, Roncero C. History of sexual, emotional or physical abuse and psychiatric comorbidity in substance-dependent patients. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:743–749. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bellis MD. Developmental traumatology: a contributory mechanism for alcohol and substance use disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:155–170. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behav Brain Sci. 1999:491–517. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore G, Mills K, Murray R, Teesson M, Farrugia P. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suicidality in inpatients with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:294–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Research Version (SCID-5-RV) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heffernan K, Cloitre M, Tardiff K, Marzuk PM, Portera L, Leon AC. Childhood trauma as a correlate of lifetime opiate use in psychiatric patients. Addict Behav. 2000;25:797–803. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ. The Importance of Degree Versus Type of Maltreatment: A Cluster Analysis of Child Abuse Types. J Psychol. 2004;138:303–324. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.138.4.303-324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. The Development of the Comprehensive Child Maltreatment Scale. J Fam Stud. 2001;7:7–28. doi: 10.5172/jfs.7.1.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hovdestad WE, Tonmyr L, Wekerle C, Thornton T. Why is Childhood Maltreatment Associated with Adolescent Substance Abuse? A Critical Review of Explanatory Models. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2011;9:525. doi: 10.1007/s11469-011-9322-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alhamzawi AO, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Benjet C, Bromet E, Chatteiji S, de Girolamo G, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gal G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Karam EG, Kawakami N, Lee S, Lépine JP, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Tsang A, Üstün TB, Vassilev S, Viana MC, Williams DR. Childhood adversities and adult psychopathology in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:378–385. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Dreifuss JA, Weiss RD, Morgenstern J, Carroll KM. The Short Inventory of Problems - Revised (SIP-R): Psychometric properties within a large, diverse sample of substance use disorder treatment seekers. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:307–314. doi: 10.1037/a0028445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation Analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCauley J, Mercer MA, Brady KT, Back SE. Trauma histories of non-treatment-seeking prescription opioid-dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;140:e139–e140. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan, Cacciola, Zanis . The Addiction Severity Index-“Lite” (ASI-“Lite”) 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Darke S, Ross J, Lynskey M. Young people with heroin dependence: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on treatment outcomes for heroin dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:447–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Peters L. Trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders: findings from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Well-Being. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:652–658. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell MR, Potenza MN. Addictions and Personality Traits: Impulsivity and Related Constructs. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s40473-013-0001-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norrholm SD, Jovanovic T, Olin IW, Sands LA, Karapanou I, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Fear Extinction in Traumatized Civilians with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Relation to Symptom Severity. Biol Psychiatry, Genes and Anxiety. 2011;69:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passetti F, Clark L, Mehta MA, Joyce E, King M. Neuropsychological predictors of clinical outcome in opiate addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JR, Upton BT, Baer RA. Brief Report: Relationships Between Facets of Impulsivity and Borderline Personality Features. J Personal Disord. 2012;27:547–552. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MK, Pickett SM, Orcutt HK. Experiential Avoidance as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Childhood Psychological Abuse and Current Mental Health Symptoms in College Students. J Emot Abuse. 2006;6:67–85. doi: 10.1300/J135v06n01_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP. Child Maltreatment and Women’s Adult Sexual Risk Behavior: Childhood Sexual Abuse as a Unique Risk Factor. Child Maltreat. 2010;15:324–335. doi: 10.1177/1077559510381112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma L, Markon KE, Clark LA. Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: A meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:374–408. doi: 10.1037/a0034418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Janavs J, Baker R, Harnett-Sheehan K, Knapp E, Sheehan M, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Amorim P, et al. MINI-Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-English Version 5.0. 0-DSM-IV. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Miller WR. Concomitance between childhood sexual and physical abuse and substance use problems: A review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:27–77. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00088-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Walker JR, Forde DR. Gender differences in susceptibility to posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:619–628. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonmyr L, Thornton T, Draca J, Wekerle C. A Review of Childhood Maltreatment and Adolescent Substance Use Relationship. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2010;6:223–234. doi: 10.2174/157340010791792581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdejo-García A, Bechara A, Recknor EC, Pérez-García M. Negative emotion-driven impulsivity predicts substance dependence problems. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-Assisted Therapies — Tackling the Opioid-Overdose Epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2063–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [WWW Document] 2013 URL http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp.

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Anestis MD, Gratz KL. The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Sullivan TP, Dixon-Gordon KL, Gratz KL. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and risky behaviors among trauma-exposed inpatients with substance dependence: The influence of negative and positive urgency. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;155:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.07.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal Individ Differ. 2001;30:669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]