Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To estimate the proportion of older adults in the emergency department (ED) who are willing and able to use a tablet computer to answer questions.

DESIGN

Prospective, ED-based cross-sectional study.

SETTING

Two U.S. academic EDs.

PARTICIPANTS

Individuals aged 65 and older.

MEASUREMENTS

As part of screening for another study, potential study participants were asked whether they would be willing to use a tablet computer to answer eight questions instead of answering questions orally. A custom user interface optimized for older adults was used. Trained research assistants observed study participants as they used the tablets. Ability to use the tablet was assessed based on need for assistance and number of questions answered correctly.

RESULTS

Of 365 individuals approached, 248 (68%) were willing to answer screening questions, 121 of these (49%) were willing to use a tablet computer; of these, 91 (75%) were able to answer at least six questions correctly, and 35 (29%) did not require assistance. Only 14 (12%) were able to answer all eight questions correctly without assistance. Individuals aged 65 to 74 and those reporting use of a touchscreen device at least weekly were more likely to be willing and able to use the tablet computer. Of individuals with no or mild cognitive impairment, the percentage willing to use the tablet was 45%, and the percentage answering all questions correctly was 32%.

CONCLUSION

Approximately half of this sample of older adults in the ED was willing to provide information using a tablet computer, but only a small minority of these were able to enter all information correctly without assistance. Tablet computers may provide an efficient means of collecting clinical information from some older adults in the ED, but at present, it will be ineffective for a significant portion of this population.

Keywords: elderly, emergency department, data collection, aged

Older adults in the United States make more than 20 million emergency department (ED) visits annually.1 Many older adults have unmet and often undiagnosed needs that negatively affect quality of life and health outcomes.2,3 Developing tools to identify and address these needs efficiently is a priority of geriatric emergency medicine research.4,5 Collecting accurate clinical information from older adults in the ED is vital to these efforts, but it is a labor-intensive process.

Mobile computing devices with a touchscreen interface have the potential to reduce the time required of ED personnel in collecting clinical information from older adults. These devices have been adopted for collecting information in a wide variety of commercial settings, including healthcare, and the feasibility of this approach has been demonstrated in the ED,6 primary care,7 and specialty clinics,8,9 with accuracy comparable with that of self-completed paper surveys.10,11 In the ED, these interventions are acceptable to most individuals,12 with more than 90% of adults in the ED preferring a technology-based approach in one study,13 and 93% reporting comfort using a computer for an alcohol use reduction program,14 but older adults differ from younger adults with regard to their familiarity with the use of electronic devices and in the prevalence of physical and cognitive impairments that might make these devices hard to use. Although it has been demonstrated that individuals with mild dementia,15 arthritis,11 and visual impairment16 can learn to use tablet computers, the extent to which older adults in the ED who have not received specific training are willing and able to use such devices to provide clinical information is unknown. The current study was designed to estimate the proportion of older adults in the ED who were willing and able to use a touchscreen tablet computer to provide answers to basic demographic and clinical questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Selection of Participants

This was a cross-sectional study of adults aged 65 and older receiving care at two academic EDs (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Cooper University Hospital, Camden, New Jersey) in the United States that serve a racially and economically diverse population of older adults. EDs were located in two regions (southeast, northeast). The primary purpose of the study was to obtain estimates of the proportion of older adults in the ED who were willing and able to use a tablet computer to provide clinical information. Enrollment occurred between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. 7 days a week for 2 months at each site. Individuals aged 65 and older were identified by review of each ED’s electronic tracking board. Individuals were excluded if they were critically ill, had altered mental status, were on a psychiatric hold, or did not speak English. Individuals were considered critically ill if their emergency severity index triage score was 1 or based on the judgment of the treating emergency provider. Altered mental status was considered present if the individual had a chief complaint of altered mental status, confusion, or delirium; a cognitive test was not used to determine eligibility. (The Six Item Screener was administered in a subset of individuals, but this information was collected after the tablet was offered to the individuals and was not used as an exclusion criterion.) The institutional review boards at both sites approved the study. Data presented here were collected as part of an assessment of eligibility for another study assessing accuracy of self-reported ability to complete a simple mobility task.17 Accordingly, all individuals in this sample had orally expressed a willingness to be screened to determine eligibility to be in a study. Consent to participate did not occur until after the tablet questions were offered to the individual, and consent was not a requirement for inclusion in this study.

Data Collection

Research assistants (RAs) collected data in in-person interviews. Before beginning the study, RAs were required to complete training in clinical research and demonstrate understanding of the study protocol. After this training, study investigators (SB, VAB) observed each RA until he or she demonstrated proficiency.

Each person who agreed to answer screening questions was asked, “Are you willing to use the tablet computer to answer these questions?” to determine whether he or she was willing to answer eight questions on a tablet. Participants were not informed that this was an important question in the study. Rather, the question was presented as, “We need this information. Are you willing to use the tablet?” For participants who agreed to use the tablet, the first two questions were designed to ensure that the person could use the tablet (e.g., mark the letter C). The next three questions assessed basic demographic information (age, sex, race). The final three questions assessed orientation (day of week, month, year). If participants were not willing to answer questions using the tablet, the relevant questions were asked orally. At the end of each survey, each participant who was willing to attempt to use the tablet was asked whether he or she would prefer to complete surveys such as this in an in-person interview or on a tablet computer. Tablet computers were chosen for data collection because they are small, portable, and lightweight. Additionally, because there is no physical keyboard, it is easier to clean than a conventional laptop computer; tablet computers were sanitized after each use using alcohol-based disinfectant wipes. Three tablets were used to collect data in this study: one ASUS Transformer TF101 (ASUSTeK Computer, Inc., Taipei, Taiwan), one Apple iPad Mini, and one Apple fourth-generation iPad (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA). Tablet questions were presented, and participant responses were recorded using an online survey instrument (Qualtrics, Provo, Utah). Responses were then transferred manually to a secure database (REDCap).

Outcomes and Analysis

The primary outcomes were willingness and ability to use a tablet. Willingness to use the tablet was determined based on the participant’s yes or no response to the above question. Ability to use a tablet was characterized by use of the tablet without assistance, how many of the eight assessment survey questions were answered correctly, whether six or more of eight questions were answered correctly, and whether all eight questions were answered correctly without assistance. The RAs observed each participant the entire time they used the tablet and indicated whether participants needed assistance in operating the device. Examples of assistance included the RA holding the tablet for the participant, reading the survey to the participant, or explaining to the participant how to scroll down on the screen to see the next question. RAs were instructed not to enter responses on behalf of participants or tell participants the answer to a question (i.e., this level of assistance was not allowed). Regardless of whether the participant was willing or able to use the tablet, the RA collected information about each participant’s prior experience using computing devices.

The Six-Item Screener for cognitive assessment was administered to a subset of participants in this study. A post hoc subgroup analysis was conducted on the subset of participants with a Six-Item Screener score of 4 or more, indicating no or mild cognitive impairment.18

Results are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or percentages with 95% confidence intervals overall, according to sociodemographic characteristics, and according to prior exposure to technology. The chi-square test was used to examine differences in willingness of specific participant subgroups to use a tablet computer. Results significant at the P ˂ .05 level are reported in the results without adjustment for multiple testing. Assuming that approximately 20% of study participants would be willing and able to use the tablet for data entry, enrolling at least 240 participants would provide 95% confidence intervals (CIs) within 5% of the point estimate for the percentage of participants willing and able to use the tablet. All data analysis was conducted using Stata version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

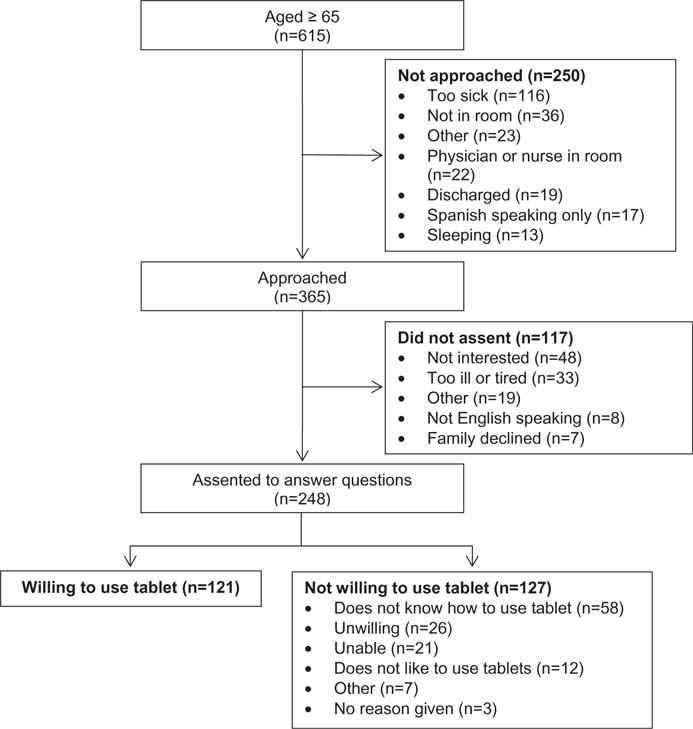

Of the 365 individuals who were approached, 248 (69%) were willing to participate (Figure 1). Of these 248 individuals, 121 (49%, 95% CI = 43–55%) were willing to use a tablet to answer the questions. Older adults were less likely to agree to use a tablet (P = .002; Table 1). Individuals who reported using a computer or touchscreen device at least once a week were more likely to agree to use a tablet (P < .001).

Figure 1.

Enrollment and eligibility of participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of All Participants and According to Willingness to Use a Tablet Computer to Provide Clinical Information

| Characteristic | All, N = 248 | Unwilling, n = 127 | Willing, n = 121 |

|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||

| Age | |||

| 65–74 | 46 (40–53) | 35 (27–44) | 58 (49–67) |

| 75–84 | 38 (31–44) | 45 (36–54) | 30 (21–38) |

| ≥85 | 16 (12–21) | 20 (13–27) | 12 (6–18) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 40 (34–46) | 33 (25–41) | 48 (39–57) |

| Female | 60 (54–66) | 67 (59–75) | 52 (43–61) |

| Race (n = 153) | |||

| White | 63 (55–70) | 57 (46–68) | 70 (59–81) |

| Black | 27 (20–35) | 30 (20–40) | 24 (13–34) |

| Hispanic | 8 (4–12) | 10 (4–17) | 5 (0–10) |

| Other | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–4) |

| Technology useda,b | |||

| Computer | 40 (34–46) | 24 (16–31) | 57 (48–66) |

| Touchscreen devicec | 30 (24–36) | 20 (13–27) | 41 (32–50) |

| None | 37 (31–43) | 50 (41–58) | 24 (16–32) |

Used at least once a week.

Not mutually exclusive.

Smart telephone or tablet.

For the 121 individuals willing to use a tablet, median completion time was 3 minutes (IQR 1 minute, 50 seconds-5 minutes, 5 seconds); 29% (95% CI = 21–37%) did not require assistance, 75% (95% CI = 67–83%) answered six or more questions correctly; 32% (95% CI = 23–49%) answered all eight questions correctly, and 12% (95% CI = 7–19%) answered all questions correctly without assistance. Individuals aged 85 and older took longer to answer the questions. The percentage of participants who answered six or more of the eight questions correctly was higher in whites than blacks (P = .02) and higher in those who reported weekly use of a touchscreen device than those who did not (P < .001) (Table 2). Of the initial 248 individuals who agreed to answer questions, only 39 (32%, 95% CI = 23–40%) were willing to use the tablet and able to answer all eight questions without assistance.

Table 2.

Of Participants Willing to Use a Tablet, Time Required to Complete Survey, Whether Assistance Required, and Accuracy of Data Input

| Characteristic | n | No Assistance Required | ≥6/8 Questions Correct | All Questions Correct | Time, Seconds, Median (Interquartile Range)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (95% Confidence Interval) | |||||

| All participants | 121 | 29 (21–37) | 75 (67–83) | 32 (23–40) | 180 (195) |

| Age | |||||

| 65–74 | 70 | 33 (22–44) | 80 (70–90) | 32 (21–43) | 160 (151) |

| 75–84 | 36 | 31 (15–46) | 72 (57–87) | 26 (11–41) | 183 (201) |

| ≥85 | 15 | 7 (0–20) | 60 (34–86) | 47 (20–73) | 296 (276) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 58 | 33 (20–45) | 76 (65–87) | 38 (25–50) | 180 (180) |

| Female | 63 | 25 (14–36) | 75 (64–86) | 27 (16–38) | 195 (223) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 47 | 25 (13–38) | 77 (64–89) | 40 (25–55) | 176 (199) |

| Black | 16 | 19 (0–39) | 44 (18–69) | 13 (0–30) | 277 (208) |

| Hispanic | 3 | 0 (0–56) | 100 (44–100) | 33 (6–79) | 271 (333) |

| Other | 1 | 0 (0–79) | 0 (0–79) | 0 (0–79) | 260 (0) |

| Technology usedb,c | |||||

| Computerd | 69 | 43 (32–55) | 81 (72–91) | 39 (27–51) | 150 (171) |

| Touchscreen devicee | 50 | 56 (42–70) | 98 (94–100) | 45 (31–59) | 126 (113) |

| None | 29 | 7 (0–16) | 55 (37–74) | 10 (0–22) | 262 (213) |

| Willing to use tablet again | |||||

| Yes | 104 | 33 (24–42) | 77 (69–85) | 31 (22–40) | 174 (191) |

| No | 16 | 0 (0–19) | 63 (38–87) | 40 (14–66) | 235 (316) |

| Preference in future | |||||

| Tablet | 31 | 45 (27–63) | 90 (80–100) | 39 (21–56) | 151 (204) |

| Oral interview | 90 | 23 (14–32) | 70 (60–80) | 30 (20–39) | 211 (197) |

n = 115.

Used at least once a week.

Not mutually exclusive.

Desktop or laptop computer.

Smart telephone or tablet.

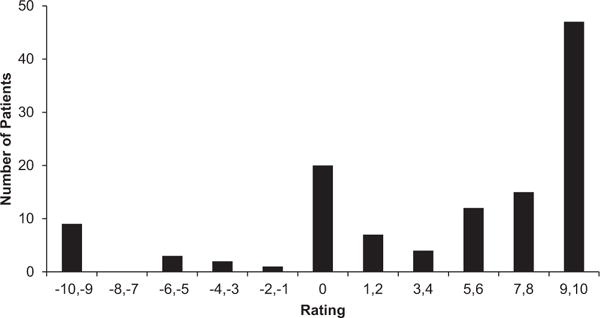

Overall, 87% of individuals who used a tablet indicated they were willing to use a tablet again for data entry, but if given the choice, 75% of those who used a tablet stated they would prefer a verbal interview rather than tablet entry in the future. The preference for a verbal interview was particularly strong in individuals aged 85 and older (93%). The majority of participants indicated that they liked using the tablet computer for data entry (71%), although 16% were neutral, and 13% disliked using the tablet, including nine (8%) participants who indicated that they strongly disliked it (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Of those willing to use a tablet computer, responses to the question “How much did you dislike or like using the tablet computer today (−10 = strongly disliked, 10 = strongly liked)?” (n = 120).

Of the 248 study participants, 153 had cognition assessed using the Six Item Screener. Of these 153, 140 (92%) had a score of 4 or more, indicating no or mild cognitive impairment, and 85 (56%) had a score of 6. Of the 140 participants with no or mild cognitive impairment, 63 (45%) were willing to try to use the tablet, and 20 (32%) of the 63 answered all tablet questions correctly (Appendix Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, 56% of this subset of participants with no or mild cognitive impairment entered an age using the tablet computer that matched their orally reported age. Eighty-two percent of these participants would be willing to use a tablet again to answer questions, but, as with the entire sample, 78% stated that they would prefer to provide information in an interview.

DISCUSSION

Approximately half of this sample of individuals in the ED aged 65 and older approached for participation in the parent study were willing to use a tablet. Of the willing, the majority required assistance in completing the questionnaire and were unable to answer all eight questions correctly. Participant factors associated with better performance included younger age, white race, and prior technology use. Overall, participants liked using the tablet for data entry, but the majority would prefer a traditional face-to-face interview in the future. These results are consistent with those of prior studies of data entry using tablet computers, which found worse data accuracy in older individuals and differences based on race and prior technology use.6,7

Fifty-one percent of older adults in the current study were willing to use a tablet, and many of those had difficulty providing correct responses, with 32% correctly answering all questions. Of participants with mild or no cognitive impairment, 45% were willing to try to use the tablet, and 32% answered all questions correctly. Of the subset of participants who were cognitively intact, 56% correctly reported their age, suggesting that these participants had difficulty using the tablet to enter this information. These findings indicate the presence of substantial barriers to incorporation of this technology in the routine care of older adults. Observed reasons for participants marking the wrong answer included difficulty touching the desired spot on the screen and difficulty getting the tablet to register when they touched the screen. In some cases, it appeared the person had difficulty reading the question but did not feel comfortable asking the RA for assistance. Individuals aged 65 to 74 were more willing to use a tablet, less likely to require assistance, more likely to get answers right, and more likely to state they would be willing to use this technology again than those aged 75 and older. Similar to previous findings,15 these differences based on participant age may represent a greater comfort with and exposure to handheld technology of younger elderly adults, because this age group was more likely to use technology weekly. It is likely that the observed unwillingness or inability of many of the oldest adults to use tablet computers may be related to factors associated with age, particularly prior exposure to this technology, rather than age itself. Over the next two decades, as the current middle-aged population become older adults, it is likely that a larger proportion of older adults will be comfortable with this technology, although other problems that increase with age, such as visual problems and loss of dexterity, are likely to remain present in this next generation of older adults and may restrict use of this technology for some individuals.

The use of tablet computers for direct data entry by individuals for clinical assessments or data collection in a study has several advantages. First, this approach reduces time required of clinical providers or research assistants. Second, people are generally more likely to disclose sensitive personal information when answering self-administered questions than in a face-to-face interview.19,20 Thus, assessments of common but sensitive problems of older adults in the ED such as elder abuse or neglect, depression, or unmet nonmedical needs may be more accurate using tablet computers.3 Third, the use of tablet computers for assessments has the potential to facilitate broad, consistent dissemination of screening instruments or questionnaires. Furthermore, if older adults can provide accurate information using tablet computers, they may be able to provide self-supplied information such as demographic and medical history directly into electronic health records.

This study has several limitations. First, there were slight differences between the tablets. The devices had displays that differed slightly in size, contrast, resolution, and sensitivity of the screen to touch. The two Apple iPad tablets offered a zoom function within the survey that the ASUS Transformer did not; this may have assisted participants with visual impairment. The iPad Mini was slightly smaller, which resulted in smaller final rendered text, whereas the iPad Mini was lighter and presumably easier for participants to handle. Additionally, although both had contrasting text and background, the Apple devices had dark text on white background, and the ASUS device had the opposite. This difference may have affected legibility.21 Tablet computers with large-text options and easy-to-use operating systems have been developed specifically for use by older adults.22 Use of such tablets may have yielded different results. One participant had difficulty using the tablet because she had long acrylic nails. Providing a stylus, which was not done in this study, may make the tablet easier for some people to use. Level of formal education, which has been shown to affect performance on electronic questionnaires, was not assessed.6,7 Study subjects were predominantly white, which may limit generalizability to more ethnically diverse populations. Delirium,23,24 which may have been present in some participants and may have contributed to unwillingness or inability to use the tablet, was not assessed for. Only English-speaking people seeking care between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. at two academic EDs in the United States were included. Willingness and ability to use tablets computers may be different for non-English speakers and for older adults seeking care in other settings. Participants who were unwilling to use the tablet were also less likely to use technology on a regular basis. This would not affect the estimate of the percentage of people who are willing and able to use a tablet but would limit the generalizability of the estimate of the percentage of people who are able to use a tablet to those who are willing to use it. This study was conducted in 2014, at which time an estimated 18% of U.S. adults aged 65 and older and 49% of adults aged 35 to 44 owned tablets. It is likely that, when younger generations turn 65, a larger percentage of these individuals will be comfortable with tablets and other forms of electronic data entry than the current population of older adults.

Finally, there was neither penalty nor reward attached to using the tablet device. In other settings, such as selfcheckout lines in a grocery store and automated voice response systems for telephone calls, people make choices regarding the use of the system based on penalties and rewards. One might choose to use the self-checkout lane in a grocery store because it is quicker even though it requires more effort, but might choose to pay a premium to speak to a human agent rather than endure frustration with an automated voice response system. Similarly, if use of a tablet was associated with some other improved service (e.g., completion expedites access to a physician), the willingness of people to use these devices (or find someone to help them use these devices) might change. Similarly, penalties or rewards for accurate data entry might also influence the quality of the information obtained.

Approximately half of this sample of older adults in the ED were willing to provide clinical information using a tablet computer, but only a small portion of these were able to enter all information correctly without assistance. Tablet computers may provide an efficient means of collecting clinical information from some older adults in the ED, but at present will likely be ineffective for a significant portion of this population. Nonetheless, if a substantial subset of older adults is willing and able to use these devices, it would result in significant labor savings for some clinical processes and research studies.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Among Patients with No or Only Mild Cognitive Impairment (Six-Item Screener Score ≥4) Characteristics of All Patients and Those Unwilling and Willing to Use a Tablet Computer to Provide Clinical Information

Table S2. Among patients with Six-Item Screener Score ≥4 and willing to use a tablet, need for assistance, accuracy or responses, and time required to complete survey (N = 63).

Acknowledgments

Dr. Platts-Mills is supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23AG038548. Dr. Jones and Dr. Braz are investigators on a study performed under a grant from Roche Diagnostics, Inc. and a study performed under a grant from AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Platts-Mills, Brahmandam, Mangipudi,, Jones. Data collection: Brahmandam, Holand, Mangipudi, Braz. Interpretation of data: Brahmandam, Holland, Hunold, Platts-Mills. Preparation of manuscript: Brahmandam, Holland, Mangipudi, Braz, Medlin, Hunold, Jones, Platts-Mills.

Sponsor’s Role: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content, accuracy, errors, or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2011 Emergency Department Summary Tables. 2015 [on-line]. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/emergency-department.htm Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 2.Pereira GF, Bulik CM, Weaver MA, et al. Malnutrition among cognitively intact, noncritically ill older adults in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens TB, Richmond NL, Pereira GF, et al. Prevalence of nonmedical problems among older adults presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:651–658. doi: 10.1111/acem.12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter C, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: introducing multidisciplinary geriatric emergency department guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:806–809. doi: 10.1111/acem.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter CR, Shah MN, Hustey FM, et al. High yield research opportunities in geriatric emergency medicine: Prehospital care, delirium, adverse drug events, and falls. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A:775–783. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herrick DB, Nakhasi A, Nelson B, et al. Usability characteristics of self-administered computer-assisted interviewing in the emergency department: Factors affecting ease of use, efficiency, and entry error. Appl Clin Inform. 2013;4:276–292. doi: 10.4338/ACI-2012-09-RA-0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hess R, Santucci A, McTigue K, et al. Patient difficulty using tablet computers to screen in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:476–480. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0500-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams CA, Templin T, Mosley-Williams AD. Usability of a computer-assisted interview system for the unaided self-entry of patient data in an urban rheumatology clinic. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2004;11:249–259. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salaffi F, Gasparini S, Ciapetti A, et al. Usability of an innovative and interactive electronic system for collection of patient-reported data in axial spondyloarthritis: Comparison with the traditional paper-administered format. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:2062–2070. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter JG, Becker A, Koch T, et al. Self-assessments of patients via tablet PC in routine patient care: Comparison with standardised paper questionnaires. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1739–1741. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.090209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenwood MC, Hakim AJ, Carson E, et al. Touch-screen computer systems in the rheumatology clinic offer a reliable and user-friendly means of collecting quality-of-life and outcome data from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:66–71. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choo EK, Ranney ML, Aggarwal N, et al. A systematic review of emergency department technology-based behavioral health interventions. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:318–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ranney ML, Choo EK, Wang Y, et al. Emergency department patients’ preferences for technology-based behavioral interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy MK, Bijur PE, Rosenbloom D, et al. Feasibility of a computer-assisted alcohol SBIRT program in an urban emergency department: patient and research staff perspectives. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim FS, Wallace T, Luszcz MA, et al. Usability of tablet computers by people with early-stage dementia. Gerontology. 2013;59:174–182. doi: 10.1159/000343986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crossland MD, Silva RS, Macedo AF. Smartphone, tablet computer and ereader use by people with vision impairment. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2014;34:552–557. doi: 10.1111/opo.12136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roedersheimer KM, Pereira GF, Jones CW, et al. Self-reported versus performance-based assessments of a simple mobility task among older adults in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, et al. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–781. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005;27:281–291. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Jamieson E, et al. Approaches to screening for intimate partner violence in health care settings: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:530–536. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.5.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greco M, Stucchi N, Zavagno D, et al. On the portability of computer-generated presentations: The effect of text-background color combinations on text legibility. Hum Factors. 2008;50:821–833. doi: 10.1518/001872008X354156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TrioBest. Best Tablets for Seniors and Elderly Senior Citizens. :2015. [online]. Available at http://www.triobest.com/best-tablets-for-seniors-and-eldery-senior-citizens/ Accessed September 2, 2016.

- 23.Carpenter CR, Griffey RT, Stark S, et al. Physician and nurse acceptance of technicians to screen for geriatric syndromes in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2011.1.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hustey GM, Meldon SW. The prevalence and documentation of impaired mental status in elderly emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:248–253. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.122057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Among Patients with No or Only Mild Cognitive Impairment (Six-Item Screener Score ≥4) Characteristics of All Patients and Those Unwilling and Willing to Use a Tablet Computer to Provide Clinical Information

Table S2. Among patients with Six-Item Screener Score ≥4 and willing to use a tablet, need for assistance, accuracy or responses, and time required to complete survey (N = 63).