Abstract

Background

The rehabilitation of depressed stroke patients is more difficult because poststroke depression is associated with disruption of daily activities, functioning, and quality of life. However, research on depression in stroke patients is limited. The aim of our study was to evaluate the interaction of demographic characteristics including gender, age, education level, the presence of a spouse, and income status on depressive symptoms in stroke patients and to identify groups that may need more attention with respect to depressive symptoms.

Methods

We completed a secondary data analysis using data from a completed cross-sectional study of people with stroke. Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale.

Results

In this study, depressive symptoms in women living with a spouse were less severe than among those without a spouse. For those with insufficient income, depressive symptom scores were higher in the above high school group than in the below high school group, but were lower in patients who were living with a spouse than in those living without a spouse.

Conclusion

Assessing depressive symptoms after stroke should consider the interaction of gender, economic status, education level, and the presence/absence of a spouse. These results would help in comprehensive understanding of the importance of screening for and treating depressive symptoms during rehabilitation after stroke.

Keywords: Depression, Demographic characteristic, Moderating effect, Stroke

Background

Depression is reportedly the most common mental disorder following stroke [1–4], with an incidence ranging from 10 to 64% [4–6]. Poststroke depression has an adverse effect on functional recovery and increases the mortality rate [7]. Furthermore, the rehabilitation of depressed stroke patients is more difficult because poststroke depression is associated with disruption of daily activities, function, and quality of life [8, 9].

Depressive symptoms may be a psychological consequence of low levels of physical functioning and different life experiences after a stroke [10]. Indeed, one study found that there was no significant association between depression levels and the pathological development of stroke such as type of stroke, side of stroke, and comorbidity [10]. Furthermore, a study on comorbidity and primary care costs found that depression was a stroke comorbidity associated with increased costs [11].

Demographic characteristics are one of factors that affect depressive symptoms in stroke patients. A meta-analysis in stroke patients reported that education level, income, and age showed significant effects on depressive symptoms [12]. Other studies have found that depressive symptoms are significantly related to presence of a spouse [13] and higher levels of education [14], while low economic status has also been associated with a higher prevalence of depression at any level of morbidity [15]. Stroke patients were also shown to receive care and emotional and physical support from their family members [16]. Support from the family was a protective factor affecting poststroke depression [17]. Indeed, the severity of depressive symptoms has been found to be associated with lower levels of certain relational variables, such as social support and satisfaction thereof [18]. The literature has shown that depressive symptoms can be reduced through interventions that aim to improve the self-concept and self-esteem, such as positive thinking, as well as social/family support [19–21]. Functional independence was also found to be a crucial factor contributing to the level of depressive symptoms [22]. Overall, the literature has found evidence for relationships between gender, age, education level, presence of a spouse, income status, and poststroke depressive symptoms.

Demographic characteristics including gender roles, family role, caregiving support, and socioeconomic status make up a shared environment and are interdependent and interaction dynamics [23–25]. There is, however, some controversy regarding the relationships between demographic characteristics and depressive symptoms: namely, one study found no significant differences or correlations between depression score and these demographic characteristics [17]. Given the chronic nature and long-term care after stroke, it seems necessary to precisely understand how depressive symptoms result from this pathology, which can be done through attending to the moderating effects of demographic variables on psychological status.

To our knowledge, little is known about the potential role of demographic factors in depression following a stroke. The aim of our study was to evaluate the interaction of demographic characteristics including gender, age, education level, the presence of a spouse, and income status on depressive symptoms after stroke and to identify groups of patients that may be at risk of depressive symptoms after stroke.

Methods

Participants

We completed a secondary data analysis using data from a completed cross-sectional study in stroke patients. The sample was a convenience sample derived from a study that aimed to create a model for participation restriction in chronic stroke survivors [26]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was reviewed and approved by the Ethic Review Board of Y University in Korea. Inclusion criteria for this study were (1) having a confirmed diagnosis of stroke based on hospital records, (2) experiencing their first stroke based on hospital records, (3) having a stroke diagnosis at least 12 months prior to data collection, (4) having sufficient communication and cognitive abilities to answer questions, and (5) living in the community. Cognitive function was assessed by using the validated Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-K) [27]; the scores can range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better cognition. In this study, subjects whose MMSE-K scores were 18 and below were excluded.

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). The reliability and validity has been verified in stroke patients [28, 29] and this scale is often used in studies of stroke outcomes [30, 31]. The CES-D scale consists of 20 items scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all the time); four items are reverse scored. The total score is calculated by summing the item scores. The Korean version of the CES-D scale has total scores ranging from 0 to 60 points. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms, with a score of 16 or greater suggesting the presence of clinical depressive symptoms [32]. The Cronbach’s α coefficient in stroke patients has been found to be 0.87 with a 95% confidence interval of 0.84–0.89 [29].

The presence of a spouse

Marital status was classified as the presence or absence of a spouse (including not married, divorced, widowed, and separated). The answers were then recoded into a dichotomous variable whether the spouse lived with the stroke patient or not.

Income status

Income status was classified as sufficient and insufficient income categories. This variable was measured subjectively by asking participants, “What was your economic status?” Participants answered on a five-point scale with answer options of “very sufficient,” “sufficient,” “average,” “somewhat insufficient,” and “very insufficient.” Participants’ answers were then recoded into a dichotomous variable indicating whether participants had experienced subjective income hardship or not. Average or above income was classified as “sufficient income” and “somewhat insufficient” and “very insufficient income” were classified as insufficient income.

Statistical analysis

The mean differences in the demographic characteristics were analyzed using independent t tests. The general linear model (GLM) is a generalization of multiple linear regression models that can flexibly measure the relationship between normally distributed dependent variables and some combination of categorical or continuous independent variables. The GLM can be used to analyze the mean differences when there is more than one independent variable. The results of the GLM can reveal the moderating effects among the independent variables. In this study, we used the univariate GLM (which involves conducting an analysis of variance for variables with two or more factors) because there was one dependent variable. A full factorial design was selected and type III sums of squares were used [33]. The parametric tests were used from an ordinal scale of the CES-D in data because Likert scales are often viewed as an interval scale [34].

Here, we determined whether there were significant main effects of gender, education level, age, income status, and the presence of a spouse on depressive symptoms. We also examined the interactions between gender, education level, age, income status, and the presence of a spouse. Specifically, we measured the interactions of gender × education level, gender × age, gender × income status, education level × age, education level × the presence of a spouse, education level × the presence of a spouse, and education level × income status, age × the presence of a spouse, age × income status, and the presence of a spouse × income status on depressive symptoms. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 23.0.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

Data from 166 stroke patients (57 women and 109 men) were analyzed. Their mean age was 53.40 years (SD = 13.47). The general characteristics of the patients and the group differences are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the number of participants according to age or presence of spouse. There were, however, significantly more male participants, participants with an education level of above high school, and participants with a sufficient income.

Table 1.

General characteristics of participants

| Category | n | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 109 | 19.38 | 10.86 | −2.12 | .036 |

| Female | 57 | 23.28 | 12.05 | ||

| Age | |||||

| < 60 | 120 | 20.92 | 10.85 | .36 | .717 |

| ≥ 60 | 46 | 20.20 | 12.84 | ||

| the presence of spouse | |||||

| yes | 108 | 20.22 | 11.35 | −.76 | .447 |

| no | 58 | 21.64 | 11.54 | ||

| Education | |||||

| Below high school | 47 | 21.26 | 12.64 | 2.56 | .012 |

| Above high school | 119 | 19.32 | 10.61 | ||

| Household income | |||||

| Sufficient income | 120 | 18.43 | 11.40 | −4.39 | .000 |

| Insufficient income | 46 | 26.67 | 9.11 | ||

Moderating effects of demographic characteristics on depression

Patients’ mean scores on the CES-D according to their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. The depressive symptoms score was not associated with education or the presence of a spouse. However, females, participants with less than a high school education, and participants with an insufficient income had significantly higher depressive symptom scores. The main effects of gender, age, education level, presence of a spouse, and income status on depressive symptoms are presented in Table 2. The main effects of gender and age were significant.

Table 2.

The moderating effects of general characteristics on depression

| df | SS | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 1 | 666.794 | 6.645 | .011 |

| Education level (below high/above high) | 1 | .107 | .001 | .974 |

| Age (< 60/≥ 60) | 1 | 417.839 | 4.164 | .043 |

| Income status (general/low) | 1 | 34.242 | .341 | .560 |

| The presence of spouse (yes/no) | 1 | 381.870 | 3.805 | .053 |

| Gender × Education level | 1 | 25.642 | .256 | .614 |

| Gender × Age | 1 | 2.099 | .021 | .885 |

| Gender × The presence of spouse | 1 | 493.127 | 4.914 | .028 |

| Gender × Income status | 1 | 165.172 | 1.646 | .202 |

| Education level × Age | 1 | .749 | .007 | .931 |

| Education level × The presence of spouse | 1 | 22.879 | .228 | .634 |

| Education level × Income status | 1 | 496.013 | 4.943 | .028 |

| Age × The presence of spouse | 1 | 78.361 | .781 | .378 |

| Age × Income status | 1 | 17.688 | .176 | .675 |

| The presence of spouse × Income status | 1 | 413.696 | 4.123 | .044 |

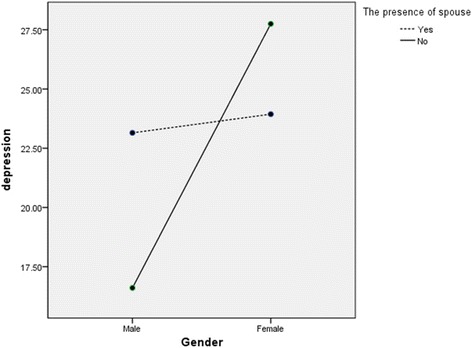

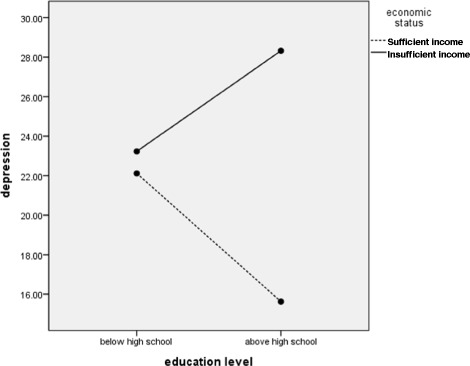

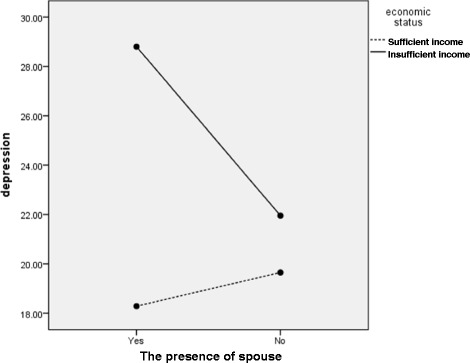

The interaction effects of gender × presence of a spouse, education level × income status, and presence of a spouse × income status on depressive symptoms were also significant. More specifically, the depressive symptom scores of women living with a spouse were significantly lower than were those of women without a spouse (Fig. 1). Furthermore, among participants with an insufficient income, the depressive symptoms scores were higher among those in the above high school group than among those in the below high school group. Furthermore, among participants in the above high school group, depressive symptom scores were lower (16.48) in the sufficient income group than in the insufficient income group (27.73). There was a trivial difference in depressive symptoms by income status among participants in the below high school group (insufficient income, 24.03; sufficient income, 24.69; Fig. 2). Finally, in the insufficient income group, the depressive symptoms of stroke patients living with a spouse were more severe than were those of patients living without a spouse. Conversely, economic status had a larger effect on stroke patients living with a spouse (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Interaction effect of gender × the presence of spouse on depression

Fig. 2.

Interaction effect of education level × income status on depression

Fig. 3.

Interaction effect of the presence of spouse education level × income status on depression

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we investigated the relationships of various demographic characteristics—including gender, age, education level, income status, and the presence of a spouse—with depressive symptoms among stroke patients, as well as the interaction effects of these variables.

In this study, the depressive symptoms scores of women living with a spouse were lower than were those of women without a spouse. By contrast, the difference in depressive symptoms scores according to the presence of a spouse was trivial among male patients. Past studies have similarly shown gender-based differences in stroke outcomes, including daily activity independence and quality of life [35]. Female stroke patients appear to be less likely to achieve independence in daily activities and have poorer physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning (manifesting as problems such as thinking difficulties, language difficulties, and less energy) after discharge [36]. Considering that spouses are the primary caregivers for most patients are physically dependent on others [37], it is possible that there are partner effects on emotional functioning, such as the development of depressive symptoms, among female stroke patients.

Family support has been reported as a protective factor for major depression in chronic diseases such as cancer [38]. Research has similarly shown that depressive symptoms are negatively correlated with social support [17]; thus, it is logical to suggest that stroke patients who do not have a spouse might be more depressed than those with a spouse. In terms of the social contextual model, which accounts for the transactional and interdependent nature of social relationships, a diagnosis of chronic illness might lead to changes that influence one’s partner as well [23–25]. However, this model cannot explain why depressive symptoms were found among male stroke patients who had a spouse in our study. There are studies suggesting gender differences in partner effects [13]. Thus, our results are also supported by a study reporting that there are no partner effects in male patients. In other words, husbands’ depressive symptoms do not appear to be influenced by the wives’ characteristics, whereas the husband’s characteristics can contribute to women’s somatic symptoms and depressive symptoms [13].

In our results, the depressive symptoms of stroke patients with an education level above high school and insufficient income were higher than were those in the sufficient income group. Education has been found to be negatively associated with general depressive symptoms [13, 14, 39, 40], likely because of its relationship with future income, socioeconomic status, and life satisfaction [41]. However, education did not have a protective role in the insufficient income group; it was only protective in the sufficient group in our study. This might be because material deprivation is an important variable in stroke patients. Patients with stroke are long-term users of health services and typically have high health care costs [42]. Low income has been found to be associated with less participation following stroke [43]. Additionally, around 20% of stroke survivors are unemployed post-stroke and around half must change jobs [37]. Thus, under conditions of material deprivation, higher levels of education do not guarantee higher income. Because there was a strong association between low income and depression among patients [15], further studies should be conducted to examine economic status changes after a stroke.

Note that this study employed a subjective measure of income status. Subjective income status is an integral aspect of one’s economic well-being because it can improve one’s assessment of one’s capacity to meet financial needs, including maintaining independent community-based living [44]. Perceived income adequacy has been reported in the literature in various ways and has been verified as a predictor of other outcome measures such as self-rated health [45], life satisfaction [46], and depressive symptoms [47].

In the same line of reasoning, with insufficient income, the presence and support of a spouse did not have positive effects on depressive symptoms in stroke patients. In our study, the depressive symptoms scores of stroke patients living with a spouse in the insufficient income bracket were higher than were those living without a spouse. Overall decline in social function and burden for both the stroke survivors and their caregivers [37] would be much greater among those with a low income status.

Stroke is a complex condition that can have multiple comorbidities [48]. Because managing complex patients requires greater clinical effort, a better understanding of this complex patient population is needed [49]. The complexity of these patients increases the need for healthcare resources and substantial family and community support; in particular, healthcare systems and services need to be redesigned to better meet the needs of these patients [49]. Personal characteristics, social determinant factors, and social/family support have been reported as some of the elements that contribute to the complexity of stroke patients [48]. Because depressive mood leads to a lowered likelihood of help-seeking intention [50], identifying the risk factors of depressive symptoms after a stroke is necessary. This study showed that assessment of risk factors should consider the interactions between gender, economic status, education level, and presence/absence of a spouse. This would also be relevant for interventions aiming to reduce depressive symptoms during stroke rehabilitation.

The results of this study help in comprehensive understanding of the importance of screening for and treating depressive symptoms during rehabilitation after stroke. In particular, our results showed that the researcher took into account the interaction between general characteristics such as gender, socioeconomic status, and the presence/absence of a spouse. It might be noted, however, that researchers must be cautious in generalizing our findings, as the sample may not be fully representative of all stroke patients, especially those who are institutionalized or have cognitive deficits. Furthermore, our sample size was rather small, which increases the likelihood of spurious associations among a large number of interactions. Investigating such a large number of potential interactions indeed presents a statistical challenge for studies with relatively small sample sizes. Moreover, the probability of making a type II error could increase due to lack of adjustment for multiple comparisons. There was a need to be cautious when interpreting these results from the point of view that chance could increase with each subsequent test. Finally, the data were all collected through a self-report questionnaire, and some of the variables, in particular income status, were subjectively measured. These facts suggest that the validity of our results might have been influenced by social desirability bias and intrinsic self-reporting bias.

Acknowledgements

No funding resources in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the first author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

JK contributed to the conception and design of the study, data collection, statistical analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. EP contributed to the statistical analysis, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethic Review Board of Yonsei University, Republic of Korea. All participants provided written consent to take part in the study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CES-D

Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale

- EP

Eun-young Park

- GLM

General linear model

- JK

Jung-Hee Kim

- MMSE-K

Mini-mental state examination

Contributor Information

Eun-Young Park, Email: eunyoung@jj.ac.kr.

Jung-Hee Kim, Phone: 82-2-2258-7816, Email: jhee90@catholic.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Astrom M, Adolfsson R, Asplund K. Major depression in stroke patients: a 3-year longitudinal study. Stroke. 1993;24:976–982. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.7.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gainotti G, Antonucci G, Marra C, Paolucci S. Relation between depression after stroke, antidepressant therapy, and functional recovery. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;7:258–261. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS. Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005;36:1330–1340. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000165928.19135.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kotila M, Numminen K, Waltimo O, Kaste M. Depression after stroke: results of the FINNSTROKE study. Stroke. 1998;29:368–372. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen G, Vestergaard K, Riis J, Lauritzen L. Incidence of post-stroke depression during the first year in a large unselected stroke population determined using a valid standardized rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90:190–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg A, Palomäki H, Lehtihalmes M, Lönnqvist J, Kaste M. Poststroke depression: an 18-month follow-up. Stroke. 2003;34:138–143. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000048149.84268.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spalletta G, Robinson RG. How should depression be diagnosed in patients with stroke? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(6):401–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chau JP, Thopson DR, Twinn S, Chang AM, Woo J. Determinants of participation restriction among community dwelling stroke survivors: a path analysis. BMC Neurol. 2009;9(49):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teoh V, Sims J, Milgrom J. Psychosocial predictors of quality of life in a sample of community-dwelling stroke survivors: a longitudinal study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2009;16(2):157–166. doi: 10.1310/tsr1602-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam SC, Lee LY, To KW. Depressive symptoms among community-dwelling, post-stroke elders in Hong Kong. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57(2):269–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brilleman SL, Purdy S, Salisbury C, Windmeijer F, Gravelle H, Hollinghurst S. Implications of comorbidity for primary care costs in the UK: a retrospective observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:274–282. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X665242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park EY, Shin IS, Kim JH. A meta-analysis of the variables related to depression in Korean patients with a stroke. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(4):537–548. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2012.42.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayotte BJ, Yang FM, Jone RN. Physical health and depression: a dyadic study of chronic health conditions and depressive symptomatology in older adult couples. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(4):438–448. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townsend AL, Miller B, Guo S. Depressive symptomatology in middle-aged and older married couples: a dyadic analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56B:S352–S364. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.S352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlton J, Rudisill C, Bhattarai N, Gulliford M. Impact of deprivation on occurrence, outcomes and health care costs of people with multiple morbidity. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(4):215–223. doi: 10.1177/1355819613493772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sit JW, Wong TK, Clinton M, Li LS, Fong YM. Stroke care in the home: the impact of social support on the general health of family caregivers. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:816–824. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li SC, Wang KY, Lin JC. Depression and related factors in elderly patients with occlusion stroke. J Nurs Res. 2003;11(1):9–18. doi: 10.1097/01.JNR.0000347614.44660.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grav S, Hellzèn O, Romild U, Stordal E. Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(1-2):111–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kneebone II, Dunmore E. Psychological management of post-stroke depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2000;39(1):53–65. doi: 10.1348/014466500163103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lincoln N, Flannaghan T, Sutcliffe L, Rother L. Evaluation of cognitive behavioural treatment for depression after stroke: a pilot study. Clin Rehabil. 1997;11(2):114–122. doi: 10.1177/026921559701100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vickery CD, Gontkovsky ST, Wallace JJ, Caroselli JS. Group psychotherapy focusing on self-concept change following acquired brain injury: a pilot investigation. Rehabil Psychol. 2006;51(1):30. doi: 10.1037/0090-5550.51.1.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badaru UM, Ogwumike OO, Adeniyi AF, Olowe OO. Variation in functional independence among stroke survivors having fatigue and depression. Neurol Res Int. 2013;2013:842980. doi: 10.1155/2013/842980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hays JC, Krishnan KR, George LK, Pieper CF, Flint EP, Blazer DG. Psychosocial and physical correlates of chronic depression. Psychiatry Res. 1997;72:149–159. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siegel MJ, Bradley EH, Gallo WT, Kasl SV. The effect of spousal mental and physical health on husbands’ and wives’ depressive symptoms, among older adults: longitudinal evidence from the health and retirement survey. J Aging Health. 2004;16:398. doi: 10.1177/0898264304264208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tower RB, Kasl SV. Depressive symptoms across older spouses: longitudinal influences. Psychol Aging. 1996;11:683–697. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi YI, Park JH, Jung M, Yoo EY, Lee JS, Park SH. Psychosocial predictors of participation restriction poststroke in Korea: a path analysis. Rehabil Psychol. 2015;60(3):286–294. doi: 10.1037/rep0000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park JH, Kwon YC. Korean version of Mini-mental state examination (MMSE-K): development of the test for the elderly. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1989;28(1):125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Park EY. Rasch analysis of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale used for the assessment of community-residing patients with stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(21-22):2075–2083. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.560333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JH, Park EY. The factor structure of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in stroke patients. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2012;19(1):54–62. doi: 10.1310/tsr1901-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim P, Warren S, Madill H, Hadley M. Quality of life of stroke survivors. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:293–301. doi: 10.1023/A:1008927431300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickard AS, Johnson JA, Feeny DH, Shuaib A, Carriere KC, Nasse AM. Agreement between self- and proxy assessment in stroke: a comparison of generic HRQL measures. Stroke. 2004;35:607–612. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110984.91157.BD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell DC. Statistical method for psychology. 7. CA: Cengage Wadwworth; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carifio J, Perla RJ. Ten common misunderstandings, misconceptions, persistent myths and urban legends about Likert scales and Likert response formats and their antidotes. J Soc Sci. 2007;3(3):106–116. doi: 10.3844/jssp.2007.106.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saini M, Shuaib A. Stroke in women. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2008;3(3):209–221. doi: 10.2174/157489008786264032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gargano JW, Reeves MJ. Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Michigan Prototype Investigators. Sex differences in stroke recovery and stroke-specific quality of life: results from a statewide stroke registry. Stroke. 2007;38(9):2541–2548. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.485482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sreedharan SE, Unnikrishnan JP, Amal MG, Shibi BS, Sarma S, Sylaja PN. Employment status, social function decline and caregiver burden among stroke survivors. A South Indian study. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332(1-2):97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarthy MJ, Sucharew HJ, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, Flaherty ML, Khatri P, Ferioli S, Adeoye O, Kleindorfer DO, Kissela BM. Age, subjective stress, and depression after ischemic stroke. J Behav Med. 2016;39(1):55–64. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9663-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiske A. The nature of depression in later life. In S. Qualls & B. Knight (Eds.), psychotherapy for depression in older adults (pp. 29–44) Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whyte EM, Mulsant BH, Vanderbilt J, Dodge HH, Ganguli M. Depression after stroke: a prospective epidemiological study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):774–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blazer DC, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;11:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity’s many challenges. BMJ. 2007;334:1016–1017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39201.463819.2C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egan M, Kubina LA, Dubouloz CJ, Kessler D, Kristjansson E, Sawada M. Very low neighbourhood income limits participation post stroke: preliminary evidence from a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:528. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1872-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Litwin H, Sapir EV. Perceived income adequacy among older adults in 12 countries: findings from the survey of health, ageing, and retirement in Europe. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):397–406. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cairney J. Socio-economic status and self-rated health among older Canadians. Can J Aging/Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement. 2000;19:456–478. doi: 10.1017/S0714980800012460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coke MM. Correlates of life satisfaction among elderly African-Americans. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 1992;47:P316–P320. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.5.P316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.St. John PD, Blandford AA, Strain LA. Depressive symptoms among older adults in urban and rural areas. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:1175–1180. doi: 10.1002/gps.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nelson ML, Hanna E, Hall S, Calvert M. What makes stroke rehabilitation patients complex? Clinician perspectives and the role of discharge pressure. J Comorbidity. 2016;6(2):35–41. doi: 10.15256/joc.2016.6.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant RW, Ashburner JM, Hong CS, Chang Y, Barry MJ, Atlas SJ. Defining patient complexity from the primary care physician's perspective: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(12):797–804. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-12-201112200-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suka M, Yamauchi T, Sugimori H. Help-seeking intentions for early signs of mental illness and their associated factors: comparison across four kinds of health problems. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):301. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2998-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during the current study is available from the first author on reasonable request.