Abstract

Advanced head and neck (H&N) tumors have a poor prognosis, and this is worsened by the occurrence of hypoxia and ischemia in the tumors. Ozonetherapy has proved useful in the treatment of ischemic syndromes, and several studies have described a potential increase of oxygenation in tissues and tumors. The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the clinical effect of ozonetherapy in patients with advanced H&N cancer in the course of their scheduled radiotherapy. Over a period of 3 years, 19 patients with advanced H&N tumors who were undergoing treatment in our department with non-standard fractionated radiotherapy plus oral tegafur. A group of 12 patients was additionally treated with intravenous chemotherapy before and/or during radiotherapy. In the other group of seven patients, systemic ozonetherapy was administered twice weekly during radiotherapy. The ozonetherapy group was older (64 versus 54 years old, P = 0.006), with a higher percentage of lymph node involvement (71% versus 8%, P = 0.019) and with a trend to more unfavorable tumor stage (57% versus 8% IVb + IVc stages, P = 0.073). However, there was no significant difference in overall survival between the chemotherapy (median 6 months) and ozonetherapy (8 months) groups. Although these results have to be viewed with caution because of the limited number of patients, they suggest that ozonetherapy could have had some positive effect during the treatment of our patients with advanced H&N tumors. The adjuvant administration of ozonetherapy during the chemo–radiotherapy for these tumors merits further research.

Keywords: altered fractionation, alternative medicine, cancer, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, tegafur

Introduction

Advanced head and neck (H&N) tumors have poor prognoses. In advanced stages, patients can die as a result of systemic metastases but most of the patients will die as a direct effect of the main tumor, or from regional node involvement. In this situation, regional disease is not, generally, amenable to surgical resection and radical treatment is usually radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy.

A way to improve the efficacy of the radiotherapy is to use altered (non-standard) fractionations that allow a higher final dose of radiation to be administered, or the same final dose but administered over a shorter time. Hyperfractionated radiotherapy (two small fractions of radiotherapy every day) and the technique of concurrent boost (one standard fraction plus another small fraction in a reduced field, every day) are the most usual altered fractionations that have produced improved clinical outcomes (1).

Another way to improve the efficiency of the radiotherapy in H&N tumors is to decrease the ischemia and hypoxia associated with the tumors. Tumor hypoxia can increase radioresistance by up to 2.5–3 times (2). Additionally, tumor hypoxia predisposes cancer cells to a physiologic selection that results in tumor cells that are more aggressive, have decreased apoptotic potential and also have additional resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy (3). In H&N cancer, tumor hypoxia has been shown to be predictive of the response to radiotherapy (4–6) and our experience to date is in concordance with these data (7). As has been demonstrated by Overgaard and Horsman's meta-analysis (8), improving tumor oxygenation can lead to better local control and increased overall survival rates following radiotherapy.

Ozonetherapy is a technique that has been used in the treatment of ischemic syndromes (9–11). In previous studies we have described a relationship between oxygenation in H&N cancer and in anterior tibialis muscles (12), as well as ozonetherapy-induced improvement in the oxygenation of the ‘most-hypoxic’ anterior tibialis muscles (13), together with improvements in the most hypoxic tumors (14).

The aim of the present prospective study was to evaluate the clinical effect, if any, of ozonetherapy administered to patients with advanced H&N cancer who were undergoing scheduled treatment with altered fractionated radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Subjects and Methods

Patients

Nineteen patients were recruited into the study. All were male with H&N tumors and were being treated in our department with altered fractionated radiotherapy over a period of 3 years. The tumors were histologically confirmed and were not suitable for surgical resection. The malignancies were advanced H&N tumors, classified as stage IV on the TNM classification (15): tumor size T4 and/or lymph node N2 or N3 (diameter ≥3 cm or multiples). The patients' performance status was required to be >70% on the Karnofsky scale. The experimental nature of the study was fully explained to the patients and written consent was obtained prior to their recruitment. The study had the full approval of the Institutional Ethical Committee.

The altered radiotherapy consisted of hyperfractionated radiotherapy (120 cGy/fraction, two fractions/day) or hypofractionated radiotherapy (dose/fraction higher than the standard 200 cGy/fraction). Hyperfractionated radiotherapy provides the option of administering a total dose that is 15% higher than standard radiotherapy while hypofractionated radiotherapy offers a quicker and more comfortable schedule of radiotherapy, but with a lower total dose. The hypofractionated schedule is applied, usually, in older patients or those with very poor performance status, or when palliative treatment is the only option. Radiotherapy was from a Cobalt60 source. Daily chemotherapy with tegafur (oral pro-drug of 5-fluorouracil, 800 mg/day) as radiosensitizer was administered to all patients (except two; see ozonetherapy group, below) during the period of radiotherapy.

For the purposes of the present study, there were two treatment groups. In addition to the scheduled radiotherapy, one group had the ozonetherapy and the other had the scheduled chemotherapy. Table 1 summarizes the relevant clinical characteristics of the patients.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients in the study

| Treatment group* | Age | Location | Stage† | T* | N* | M* | Node size ≥5 cm+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo | 48 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2a | – | – |

| Chemo | 49 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2a | – | – |

| Chemo | 52 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2c | – | – |

| Chemo | 61 | Hypopharynx | IVa | 4 | 0 | – | – |

| Chemo | 61 | Hypopharynx | IVa | 3 | 2c | – | – |

| Chemo | 53 | Hypopharynx | IVa | 3 | 2a | – | – |

| Chemo | 52 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2c | – | – |

| Chemo | 48 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2b | – | – |

| Chemo | 58 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 0 | – | – |

| Chemo | 61 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 1 | – | – |

| Chemo | 57 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2c | – | – |

| Chemo | 51 | Oropharynx | IVb | 2 | 3 | – | 6 × 4 |

| Ozone | 52 | Nasopharynx | IVa | 4 | 2c | – | 5 × 5 |

| Ozone | 68 | Hypopharynx | IVc | 3 | 2b | Yes | – |

| Ozone | 53 | Hypopharynx | IVc | 4 | 3 | Yes | 12 × 10 |

| Ozone | 74 | Oropharynx | IVa | 4 | 2c | – | 5 × 3.5 |

| Ozone | 63 | Supraglottis | IVb | 2 | 3 | – | 8.5 × 5.5 |

| Ozone | 67 | Oral cavity | IVb | 4 | 3 | – | 8.5 × 5.5 |

| Ozone | 70 | Oropharynx | IVa | 2 | 2c | – | – |

*Abbreviations: Chemo, chemotherapy group; Ozone, ozonetherapy group; T, tumor; N, lymph node; M, systemic metastases.

†Tumor stage according to AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 5th Edn (15): stage IVc, systemic metastases; stage IVb, lymph node >6 cm; stage IVa, T4 without features from IVb or IVc.

+Node largest diameters clinically measured when lymph node size ≥5 cm.

Chemotherapy Group

There were 12 patients in this group, with an age range between 48 and 61 years. They had been referred to our hospital by the Medical Oncology Department from other hospitals without radiotherapy facilities. Intravenous chemotherapy was administered as neoadjuvant (before radiotherapy) in 11 patients and concurrent (during radiotherapy) in two patients, one of whom received neoadjuvant chemotherapy as well. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy consisted of combinations of intravenous taxotere, platinum and 5-fluorouracil over four cycles (range 3–5 cycles). Concurrent chemotherapy was taxotere administered weekly over the 8 weeks of radiotherapy. All 12 patients received tegafur daily (800 mg/day, orally) as radiosensitizer over the period of the radiotherapy. All the patients were treated with hyperfractionated radiotherapy, with a mean final dose of 78.6 Gy (range 74.4–82.8 Gy)

Ozonetherapy Group

There were seven patients in this group with an age range between 52 and 74 years. These patients represent the H&N cancer patients from among those with a variety of other cancers receiving ozonetherapy in our Department. Ozonetherapy was administered twice weekly over the course of the radiotherapy. Of the seven patients, four were treated with the planned hyperfractionated radiotherapy (two fractions/day) and, due to the advanced stage of the disease and patient preference, the other three patients were treated with hypofractionated radiotherapy (one fraction/day; a higher-than-standard-dose/fraction and a lower total dose). Overall, the seven patients in this group received a mean final dose of 75.3 Gy (range 65–81.6 Gy). Of these seven patients, two did not complete the oral tegafur treatment over the period of the radiotherapy because of limited tolerance.

Ozonetherapy Technique (OT)

Ozonetherapy was administered twice a week over the period of the radiotherapy. Using clinical-grade O2, the O3/O2 gas mixture was prepared with an OZON 2000 device (Zotzmann + Stahl GmbH, Plüderhausen, Germany) and sterilized by passage through a sterile 0.20 μm filter. Systemic OT was by autologous autohemotransfusion or by rectal insuflation. The autohemotransfusion procedure involved the extraction of 200 ml venous blood into heparin (25 IU/ml) and CaCl2 (5mM). In a sterile single-use 300 ml container, the blood was mixed with 200 ml of the O3/O2 gas mixture at a concentration of 60 μg/ml and then slowly re-introduced into the patient. The blood was extra-corporeal for 15–30 min and there were no adverse reactions except hematoma formation in the area of venous injection. Rectal insuflation was employed when the performance status was low, or at the preference of patient. This procedure consisted in rectal insuflation of 300 ml of O3/O2 gas mixture at a concentration of 60 μg/ml. The main side effects were transient meteorism and constipation in some patients. In three patients, the intravenous route alone was used, in one patient the rectal insuflation route alone was used and in the other three patients we began the ozonetherapy using autohemotransfusion but then changed to rectal insuflation. Among the seven patients, there were 49 (mean of seven per patient) autohemotransfusion procedures, and 41 (mean of six per patient) rectal insuflations.

Statistical Analyses

The SPSS software package (version 11.0 for Windows) was used for all analyses. Two-sided tests were applied for significance. Data are expressed as means with their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Age between groups was compared by the two-sided non-paired Student's t-test. Nominal group data were compared by chi-square test. Overall survival was evaluated by actuarial analysis using the log-rank test of Kaplan–Meier estimates. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The patients in the ozonetherapy group were significantly older than the chemotherapy group: 64 years (range 56–72) and 54 years (range 51–57), respectively (P = 0.006).

The ozonetherapy group had more advanced lymph node involvement. All patients had multiple nodes and/or nodes ≥6 cm, while in the chemotherapy group only 50% of the patients had this advanced node involvement (P = 0.080). In the ozonetherapy group, 71% of patients had large nodes ≥5 cm, while in the chemotherapy group only one patient (8%) had a node ≥5 cm (P = 0.019).

Additionally, there was a trend towards the most unfavorable stages IVb (nodes >6 cm) or IVc (systemic metastasis) in the ozonetherapy group than in the chemotherapy group (57% versus 8%; P = 0.073).

The percentages of clinically complete response in the irradiated areas were 29% versus 50% in the ozonetherapy and chemotherapy groups, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

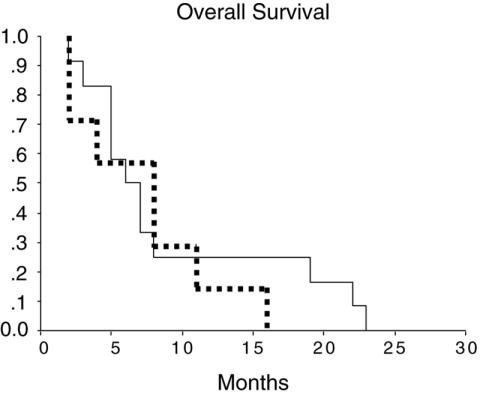

Median overall survival in the ozonetherapy group was 8 months (median 3–13 months) while the median overall survival in the chemotherapy group was 6 months (median 4–8 months). These differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overall survival was not statistically different between the ozonetherapy (dotted line) and the chemotherapy (solid line) groups of patients. The median survival was 8 (3–13) and 6 (4–8) months, respectively.

Discussion

Tumor hypoxia is a poor prognostic factor for response to radiotherapy in patients with H&N carcinomas (4–7). Modification of the levels of hypoxia with therapy has been shown to have an improved effect on therapeutic outcomes (8). A special workshop sponsored by the National Cancer Institute established the need to investigate methods to overcome tumor hypoxia (16). In a previous study we were able to demonstrate that ozonetherapy could increase oxygenation in the most poorly oxygenated H&N tumors (14). An increase in common carotid blood flow and diastolic velocities, as measured by Doppler, as a result of ozonetherapy suggested a regional vascular effect (17) and was an added incentive for us to explore the clinical benefit of ozonetherapy administered to our patients during their scheduled radiotherapy.

Systemic ozonetherapy by autohemotransfusion, or by rectal insuflation, precludes airway involvement and, as such, avoids the possibility of lung toxicity. At the appropriate concentration, ozonetherapy leads to a transient oxidative stress. This has been postulated to induce an up-regulation of antioxidants in the circulation not only in the autohemotransfusion procedure (18,19) but also using rectal insuflation (20,21).

The various oxidized molecules and the specific antioxidants generated are the basis of ozonetherapy. Several mechanisms have been postulated to interact in the observed improvement in blood flow and oxygenation. These include: (i) a displacement to the right in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve, leading to a higher oxygen release in the tissues secondary to a pH decrease in erythrocytes (the ‘Bohr effect’) (22) with or without an increase in the production of 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (23); (ii) an improvement in erythrocyte flexibility resulting in a decrease in blood viscosity and resistance (11,24); (iii) nitric oxide and vasoactive substance release could result in an additional decrease in vascular resistance (25).

However, tumor vessels have structural and functional abnormalities with decreased or near-absent auto-regulatory mechanisms (26) and, as such, the effects of ozonetherapy on tumor vasculature need to be evaluated in specifically designed in vivo and in vitro studies.

Our ozonetherapy patient group had a poorer prognosis. The patients were older, with larger tumor nodes, at more advanced stages of the disease and with a less-optimized radiotherapy schedule, i.e. lower mean final doses, and three of seven patients were treated with hypofractionated instead of hyperfractionated radiotherapy. Despite this, the patients in this group were not disadvantaged, as evidenced by the observation that overall survival was not lower than the chemotherapy group even though the latter received a more aggressive chemotherapy and a higher final dose of radiotherapy. These results suggest that ozonetherapy, when applied during radiotherapy, could have had some beneficial effect in these patients with advanced H&N tumors. Further studies are under way in our Department to extend the numbers and types of cancer patients receiving ozonetherapy with a view to making more detailed comparisons of the benefits of ozonetherapy as adjuvant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy together with other adjuvant treatment such as carbogen breathing.

It is of note that an isolated report in the early 1970s had indeed postulated the potential improvement in the effects of radiotherapy by ozonetherapy in advanced gynecological tumors (27). We tend to favor the explanation of the potential positive effect during chemo–radiotherapy as being due to the effects on ischemia–hypoxia, as described above, as well as an increase in sensitivity of tumor cells to chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (28). Other potential contributions to the mechanism-of-action that have been described include increase in cytokine production (29,30) among others (31).

In conclusion, tumor hypoxia and ischemia are known to limit treatment efficacy and, hence, the alleviation of such a predisposition to poorer treatment outcome is seen as beneficial. Ozonetherapy can produce an improvement in blood flow and oxygenation in some tissues and although our findings need to be viewed with caution because of the limited number of patients enrolled, ozonetherapy appears to have had some positive effect during the treatment of patients with advanced H&N tumors. The potential usefulness of ozonetherapy as an adjuvant in chemo–radiotherapy for these tumors warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Dr Peter R. Turner of t-SciMed (Reus, Spain). This work was partially supported by a grant (FUNCIS 98-31) from the Health and Research Foundation of the Autonomous Government of the Canary Islands (Spain).

References

- 1.Nguyen LN, Ang KK. Radiotherapy for cancer of the head and neck: altered fractionation regimens. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:693–701. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00906-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, Hornsey S, Scott OCA. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1953;26:638–648. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-312-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Graeber TG, Osmanian C, Jacks T, Housman DE, Koch CJ, Lowe SW, et al. Hypoxia-mediated selection of cells with diminished apoptotic potential in solid tumours. Nature. 1996;379:88–91. doi: 10.1038/379088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatenby RA, Kessler HB, Rosenblum JS, Coia LR, Moldofsky PJ, Hartz WH, et al. Oxygen distribution in squamous cell carcinoma metastases and its relationship to outcome of radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1988;14:831–838. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordsmark M, Overgaard M, Overgaard J. Pretreatment oxygenation predicts radiation response in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Radiother Oncol. 1996;41:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(96)91811-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, Scher RL, Dewhirst MW. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavo B, Lloret M, Perez JL, Lopez L, Suarez G, Macias D, et al. Association of tumor oxygenation with complete response, anemia and erythropoietin treatment. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol (ASCO) J Clin Oncol. 2002;21:443. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overgaard J, Horsman MR. Modification of Hypoxia-Induced Radioresistance in Tumors by the Use of Oxygen and Sensitizers. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1996;6:10–21. doi: 10.1053/SRAO0060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rovira G, Galindo N. La ozonoterapia en el tratamiento de las úlceras crónicas de las extremidades inferiores. Angiologia. 1991;2:47–50. [in Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero A, Menéndez S, Gómez M, Ley J. La Ozonoterapia en los estadios avanzados de la aterosclerosis obliterante. Angiologia. 1993;45:146–148. [in Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giunta R, Coppola A, Luongo C, Sammartino A, Guastafierro S, Grassia A, et al. Ozonized autohemotransfusion improves hemorheological parameters and oxygen delivery to tissues in patients with peripheral occlusive arterial disease. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:745–748. doi: 10.1007/s002770100377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clavo B, Perez JL, Lopez L, Suarez G, Lloret M, Morera J, et al. Influence of haemoglobin concentration and peripheral muscle pO2 on tumour oxygenation in advanced head and neck tumours. Radiother Oncol. 2003;66:71–74. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00391-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clavo B, Perez JL, Lopez L, Suarez G, Lloret M, Rodriguez V, et al. Effect of ozone therapy on muscle oxygenation. J Altern Complement Med. 2003;9:251–256. doi: 10.1089/10755530360623365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clavo B, Perez JL, Lopez L, Suarez G, Lloret M, Rodriguez V, et al. Ozone therapy for tumor oxygenation: A pilot study. eCAM. 2004;1:93–98. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming ID, Cooper JS, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Kennedy BJ, Murphy GP, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 5th Edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone HB, Brown JM, Phillips TL, Sutherland RM. Oxygen in human tumors: correlations between methods of measurement and response to therapy. Radiat Res. 1993;136:422–434. Summary of a workshop held November 19–20, 1992, at the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Maryland. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clavo B, Catala L, Perez JL, Rodriguez V, Robaina F. Effect of ozone therapy on cerebral blood flow: A preliminary report. eCAM. 2004;1:315–320. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez F, Menendez S, Wong R. Decrease of blood cholesterol and stimulation of antioxidative response in cardiopathy patients treated with endovenous ozone therapy. Free Radic Biol Med. 1995;19:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00201-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bocci V. Does ozone therapy normalize the cellular redox balance? Implications for therapy of human immunodeficiency virus infection and several other diseases. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leon OS, Menendez S, Merino N, Castillo R, Sam S, Perez L, et al. Ozone oxidative preconditioning: a protection against cellular damage by free radicals. Mediators Inflamm. 1998;7:289–294. doi: 10.1080/09629359890983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peralta C, Leon OS, Xaus C, Prats N, Jalil EC, Planell ES, et al. Protective effect of ozone treatment on the injury associated with hepatic ischemia-reperfusion: antioxidant-prooxidant balance. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:191–196. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppola L, Giunta R, Verrazzo G, Luongo C, Sammartino A, Vicario C, et al. Influence of ozone on haemoglobin oxygen affinity in type-2 diabetic patients with peripheral vascular disease: in vitro studies. Diabetes Metab. 1995;21:252–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bocci V, Valacchi G, Corradeschi F, Aldinucci C, Silvestri S, Paccagnini E, et al. Studies on the biological effects of ozone: 7. Generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) after exposure of human blood to ozone. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 1998;12:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verrazzo G, Coppola L, Luongo C, Sammartino A, Giunta R, Grassia A, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen, oxygen-ozone therapy, and rheologic parameters of blood in patients with peripheral occlusive arterial disease. Undersea Hyperb Med. 1995;22:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valacchi G, Bocci V. Studies on the biological effects of ozone: 11. Release of factors from human endothelial cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2000;9:271–276. doi: 10.1080/09629350020027573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaupel P, Kallinowski F, Okunieff P. Blood flow, oxygen and nutrient supply, and metabolic microenvironment of human tumors: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6449–6465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernuss P, Muller-Tyl E, Dimopoulos J. Ozone-oxygen injection in gynecological radiotherapy. Strahlentherapie. 1974;148:242–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bocci V, Luzzi E, Corradeschi F, Paulesu L, Di Stefano A. Studies on the biological effects of ozone: 3. An attempt to define conditions for optimal induction of cytokines. Lymphokine Cytokine Res. 1993;12:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanker KS, Kroczek R. In vitro synergistic activity of 5-fluorouracil with low-dose ozone against a chemoresistant tumor cell line and fresh human tumor cells. Chemotherapy. 1990;36:147–154. doi: 10.1159/000238761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bocci V, Paulesu L. Studies on the biological effects of ozone 1. Induction of interferon gamma on human leucocytes. Haematologica. 1990;75:510–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bocci V. Ozonetherapy as a possible biological response modifier in cancer. Forsch Komplementarmed. 1998;5:54–60. doi: 10.1159/000021077. (Research Complementary Medicine, German/English) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]