Abstract

Background and purpose

To achieve a common understanding when dealing with long bone fractures in children, the AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (AO PCCF) was introduced in 2007. As part of its final validation, we present the most relevant fracture patterns in the upper extremities of a representative population of children classified according to the PCCF.

Patients and methods

We included children and adolescents (0–17 years old) diagnosed with 1 or more long bone fractures between January 2009 and December 2011 at the university hospitals in Bern and Lausanne (Switzerland). Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed and fractures were classified from standard radiographs.

Results

Of 2,292 upper extremity fractures in 2,203 children and adolescents, 26% involved the humerus and 74% involved the forearm. In the humerus, 61%, and in the forearm, 80% of single distal fractures involved the metaphysis. In adolescents, single humerus fractures were more often epiphyseal and diaphyseal fractures, and among adolescents radius fractures were more often epiphyseal fractures than in other age groups. 47% of combined forearm fractures were distal metaphyseal fractures.

Only 0.7% of fractures could not be classified within 1 of the child-specific fracture patterns. Of the single epiphyseal fractures, 49% were Salter-Harris type-II (SH II) fractures; of these, 94% occurred in schoolchildren and adolescents. Of the metaphyseal fractures, 58% showed an incomplete fracture pattern. 89% of incomplete fractures affected the distal radius. Of the diaphyseal fractures, 32% were greenstick fractures. 24 Monteggia fractures occurred in pre-school children and schoolchildren, and 2 occurred in adolescents.

Interpretation

The pattern of pediatric fractures in the upper extremity can be comprehensively described according to the PCCF. Prospective clinical studies are needed to determine its clinical relevance for treatment decisions and prognostication of outcome.

In 2007, a new classification for long bone fractures in children and adolescents, the AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF) (Slongo et al. 2007b) was developed and evaluated according to a 3-phase concept proposed by Audige et al. (2005). Following the initial validation phase and during its development (Audigé et al. 2004, Slongo et al. 2006), the classification was found to be reliable and accurate among a panel of experienced pediatric trauma surgeons (Slongo et al. 2006), and a large group of surgeons with various levels of experience in treating children’s fractures (Slongo et al. 2007a).

This study is part of the third and final PCCF validation phase, where the classification was applied in the context of a retrospective clinical study and using new specialized AO Comprehensive Injury Automatic Classifier (AOCOIAC) software (www.aofoundation.org/aocoiac). Epidemiological data relating to this patient cohort have been published recently (Joeris et al. 2014).

In 2 papers, the morphological patterns of fractures of the upper and lower extremity are presented (this paper and Joeris et al. (2016), in this issue of Acta Orthopaedica). In addition, following a previous publication by Slongo et al. (2007c), a third paper specifically covers the occurrence and distribution of multifragmentary fractures (Audigé et al. (2016), also in this issue). This first paper presents the pediatric fracture patterns in the upper extremity coded according to the PCCF.

Patients and methods

All the patients included in this study were diagnosed with 1 or more long bone fractures between January 2009 and December 2011, in 2 (primary and tertiary care) university hospitals in Lausanne and Bern. Both hospitals treat approximately 80% of children and adolescents in their respective areas of provision of fracture care (Joeris et al. 2014). We included all fractures with open physes that were documented in the patient information system of each clinic. Open physes were confirmed by an experienced child trauma surgeon in each clinic, at the time of classifying the fractures from standard anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs. No inclusion criteria relating to fracture management/therapy were set.

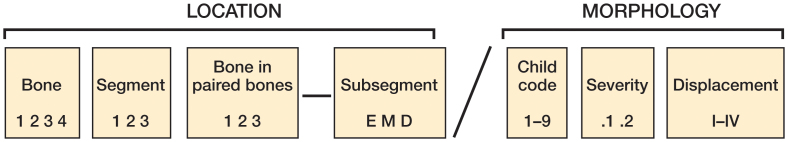

Patient charts were retrospectively reviewed for data extraction, documentation, and fracture classification according to the AO PCCF system (Slongo et al. 2006). The AO PCCF is based on the Müller AO classification of fractures (Müller et al. 1990), and it was adapted specifically for the needs of the growing skeleton—including several dimensions related to location and morphology (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall structure of the AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (AO PCCF). Fracture location is identified by the fractured long bone (1 = humerus, 2 = radius/ulna, 3 = femur, and 4 = tibia/fibula) and its injured segments (1 = proximal, 2 = shaft, 3 = distal). If only a single bone of the forearm or the lower leg is fractured, a small letter, describing the bone ("r", "u", "t", or "f") is added after the segment code. The capital letter that follows identifies the fracture type as epiphyseal (E) or metaphyseal (M) for proximal or distal fractures, or diaphyseal (D) for shaft fractures. Fracture morphology is identified by a code for specific child patterns related to the fracture type, a severity code (occurrence of multifragmentation, distinguishing between simple and wedge or complex fractures), and—if required—an additional displacement code for supracondylar or radial head fractures.

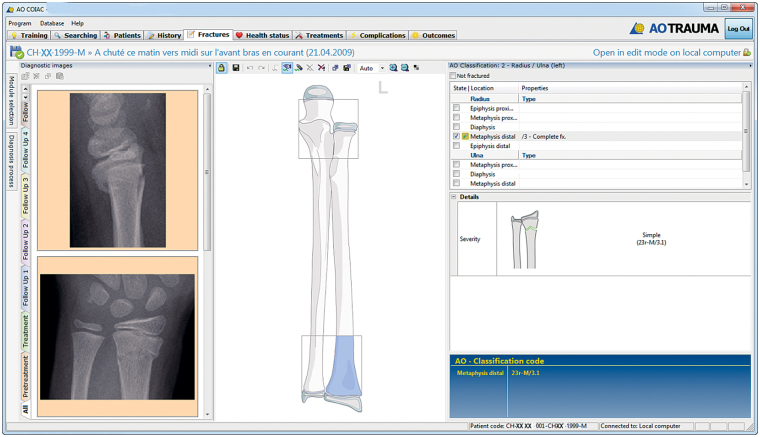

Patient and fracture data, including radiographs, were collected using the AOCOIAC software (Figure 2). AOCOIAC is PC-based software with a skeleton interface facilitating fracture classification and coding via specific modules, including the Müller AO classification system (Müller et al. 1990) and the AO pediatric classification system (Slongo et al. 2007b) for long bone fractures, and it also has a newly developed CMF fracture classification system (Audige et al. 2014) in version 4.0.

Figure 2.

Screen shot of the AOCOIAC interface with documentation of a distal radius fracture caused by a fall.

Patient demographics included age, sex, and BMI. The BMI was only available for 80% of patients (643 of 801) from the Children’s Hospital in Bern who were older than 2 years. The children were categorized in 1 of the 5 following categories, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) BMI-for-age percentiles for boys and girls: "severely thin", "thin", "normal", "overweight" and "obese" (www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/bmi_for_age/en/). Furthermore, 4 age groups were considered: (1) infants and toddlers (< 2 years), (2) pre-school children (2 to <6 years), (3) schoolchildren (6 to <11 years), and (4) adolescents (11 to 17 years). The date of occurrence of the injuries, as well as their causes, were also documented; these are presented and discussed elsewhere (Joeris et al. 2014).

The whole study cohort had 2,716 patients with 2,730 trauma events and 2,840 fractured long bones. For this study, 2,203 patients with 2,268 trauma events and 2,292 documented fractured long bones in the upper extremity were identified.

Statistics

After anonymization, data were transferred into intercooled Stata software version 12 for analysis. Fracture location (bone, segment, and type) and child-specific morphological patterns (child code) within each location, including both combined fractures of the radius and the ulna (hereon referred to as "combined fractures in paired bones") and fracture displacement (supracondylar and radial head fractures), were cross-tabulated with absolute and relative frequencies according to patient age group. The distributions of fracture characteristics (e.g. location according to subtype) across age groups were assessed using the chi-square test.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval from both local authorities was obtained (Lausanne: protocols 118/13 and 374/15; Bern: registry 23-10-12). As this was a retrospective study involving a large patient cohort, and data were anonymized and collected centrally, no patient consent was required.

Results

Demographics

Patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with 2,292 upper extremity fractures

| Parameter | Patients n (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 2,203 |

| Agea, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.8 (3.7) |

| Median (range) | 8 (0–17) |

| Age classes | |

| Infants and toddlers (< 2 years) | 98 (4) |

| Pre-school children (2 to <6 years) | 570 (26) |

| Schoolchildrenb (6 to <11 years) | 938 (43) |

| Adolescents (11 to 17 years) | 597 (27) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 896 (41) |

| Male | 1,307 (59) |

| BMI classesc | |

| Severely thin | 28 (4) |

| Thin | 50 (8) |

| Normal | 399 (62) |

| Overweight | 94 (15) |

| Obese | 72 (11) |

Age at the time of event, truncated.

Corresponds to middle childhood.

The BMI range according to the WHO could only be calculated for Bern patients aged 2 years and older, for whom height and weight measurements were available.

Fracture location

Of all fractured long bones in the upper extremity, 26% (602 of 2,292) involved the humerus and 74% (1,690 of 2,292) involved the forearm (Table 2). In the humerus, single distal fractures involving the metaphysis accounted for 61% (366 of 602), and in the radius for 80% (689 of 858). Adolescent humerus fractures were the only group where all segments and sub-segments were approximately equally affected (Table 2), and more epiphyseal fractures (proximal and distal; 37%, 40 of 107) and diaphyseal fractures (12%, 13 of 107) were documented than in other age groups (p < 0.001). Epiphyseal radius fractures were more frequent in adolescents than in other age groups (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Distribution of fractures according to segment and type within bones. Values are n (%)

| Infants/ | Pre-school | School | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | Type | toddlers | children | children | Adolescents | Total |

| Humerus (1) | 25 | 227 | 243 | 107 | 602 | |

| Proximal | E | 0 | 3 | 7 | 18 | 28 |

| M | 2 | 14 | 31 | 30 | 77 | |

| Shaft | D | 2 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 29 |

| M | 19 | 156 | 168 | 23 | 366 | |

| Distal | E | 2 | 43 | 30 | 22 | 97 |

| Multilevela | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | |

| Radius/Ulna (2) | 74 | 364 | 735 | 517 | 1,690 | |

| Radius | 35 (47) | 120 (33) | 430 (59) | 273 (53) | 858 (51) | |

| Proximal | E | 0 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 18 |

| M | 1 | 1 | 20 | 11 | 33 | |

| Shaft | D | 2 | 10 | 14 | 7 | 33 |

| M | 32 | 106 | 351 | 200 | 689 | |

| Distal | E | 0 | 1 | 34 | 50 | 85 |

| Ulna | 4 (5) | 41 (11) | 30 (4) | 24 (5) | 99 (6) | |

| Proximal | E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 1 | 25 | 9 | 14 | 49 | |

| Shaft | D | 0 | 16 | 17 | 5 | 38 |

| M | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 11 | |

| Distal | E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Combined | 35 (47) | 203 (56)b | 275 (37)c | 220 (43)d | 733 (44) | |

| Total | 99 | 591 | 978 | 624 | 2,292 |

D: diaphysis; E: epiphysis; M: metaphysis.

All 5 fracture events included 2 fracture locations.

Including 1 fracture event with 2 fracture locations in the ulna.

Including 2 fracture events with 2 fracture locations in the radius and 1 event with 3 fracture locations in the radius and ulna.

Including 1 fracture event with 2 fracture locations in the radius and 2 events with 3 locations in the radius and ulna.

The majority of combined fractures in the forearm (including only 1 fracture per bone) occurred distally, with combined distal metaphyseal fractures accounting for 47% (343 of 726). There were more combined epiphyseal fractures in the radius and ulna in schoolchildren and adolescents than in infants/toddlers and pre-school children (p < 0.001) (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Fracture morphology

0.7% of fractures (15 of 2,292) could not be classified in 1 of the child-specific fracture patterns and were therefore classified as "other -/9" (e.g. 21u-M/9). "Other" fracture patterns were most frequently observed in the distal humerus (10 of 15).

The most frequently encountered patterns in single epiphyseal fractures were Salter-Harris type-II (SH II) fractures (49%, 108 of 222). 94% (102 of the 108) occurred in schoolchildren and adolescents (mostly in the distal radius) (Table 4, see Supplementary data). Of all the SH IV fractures, 36 of 66 affected the distal humerus in pre-school children, representing three-quarters of the epiphyseal fractures in this age group.

58% of metaphyseal fractures (702 of 1,200) were classified as "incomplete" (including torus/buckle or greenstick fractures) (Table 5). Regardless of age, 89% of these fractures (626 of 702) affected the distal radius. The majority of incomplete fractures were documented in schoolchildren and adolescents. Of all complete fractures, 72% (332 of 458) were found in the distal humerus.

Greenstick fractures were the most frequent diaphyseal fractures (31 of 96), representing 13 of 35 in schoolchildren and 9 of 23 in adolescents (Table 6).

26 Monteggia fractures were diagnosed and, of those, 24 occurred in pre-school children and schoolchildren. Monteggia fractures with the ulna fractured in the diaphysis were distributed approximately equally across pre-school children (n = 8) and schoolchildren (n = 7), whereas Monteggia fractures with the ulna fractured in the proximal metaphysis were diagnosed 8 times in pre-school children and only once in schoolchildren (Tables 5 and 6, see Supplementary data).

Of all the documented combined fractures of the radius and ulna, distal metaphyseal fractures were most frequent; of those, incomplete fractures accounted for 63% (218 of 345) (Table 7, see Supplementary data). Of the 164 diaphyseal fractures, 33% (54 of 164) were greenstick fractures of the radius and the ulna. The complete oblique fracture pattern occurred 3 times more often in the ulna than in the radius.

Discussion

Fracture classification is necessary to improve the communication about fractures, to improve research documentation on fractures, and to allow comparability of data. A fracture classification can also be used for teaching purposes, and can aid the treating physician in planning fracture management (Martin and Marsh 1997, Audige et al. 2005, Kamphaus et al. 2015). Large-scale epidemiological studies, like this study, are essential to gain a better understanding of similarities and differences in fracture patterns among age groups and sexes, and to identify injury mechanisms and risk factors (Landin 1983, Meling et al. 2009, Schalamon et al. 2011, Joeris et al. 2014).

A valid classification must be reliable and accurate, clinically useful, and comprehensive (so that any fracture can be classified)—and yet it should be easy to use. The PCCF showed high reliability and accuracy (Slongo et al. 2006, 2007a), and was used successfully for this large retrospective cohort (Joeris et al. 2014). For the upper extremity, only 0.7% of fractures could not be diagnosed within 1 of the specific child fracture patterns and had to be classified as "other", highlighting the comprehensiveness of the PCCF.

For epiphyseal fractures, Salter-Harris is the most frequently used classification (Carson et al. 2006), but due to a lack of detail, several improvements have been suggested over the years (Salter and Harris 1963, Ogden 1981, Peterson 1994a, b, Peterson et al. 1994). In 2014, the Ogden and Petersen classifications were applied to 292 physeal fractures of the distal radius, and after finding 96 cases that could not be classified into a specific category, 5 additional fracture types were proposed (Sferopoulos 2014). In our large-scale classification, only 5 epiphyseal fractures had to be classified as "other", indicating that the Salter-Harris—forming the basis of the classification of physeal fractures in the AO PCCF—is sufficient and comprehensive enough to classify epiphyseal fractures.

As children grow, their bone quality and activities change, and therefore fracture types also change. In accordance with previously published reports, schoolchildren and adolescents were the most affected groups; and the forearm was the most common fracture location (either radius alone or in combination with the ulna), with the distal segment being mostly affected (Cheng and Shen 1993, Kraus and Wessel 2010, Schalamon et al. 2011). Single epiphyseal fractures occurred most frequently in adolescents and schoolchildren, with a predominance of the SH II pattern, as shown previously (Mann and Rajmaira 1990, Brown and DeLuca 1992, Hart et al. 2006).

The distribution of the different Monteggia-type fractures was also found to be age-specific (Bado 1967). Of Bado type-II or -III Monteggia fractures, 8 of 10 occurred in pre-school children, whereas Bado type-I Monteggia fractures occurred equally often in pre-school children and schoolchildren. Overall, type-I Bado fractures occurred most often (62%), which corresponds to previously published data showing a prevalence of up to 70% of Bado type-I fractures (Stanley and de Ia Garza 2001).

Galeazzi fractures or Galeazzi-equivalent fractures are rare lesions in children (Landfried et al. 1991, Waters 2001). This was confirmed in our study, as not a single fracture of this type was observed among 1,690 forearm fractures.

Our study had some limitations, in particular its retrospective study design. The quality of the data was dependent on the completeness of the patient charts, specifically regarding the availability of the radiographs for classification. Relevant treatment and outcome data were not collected in a uniform format, which would allow assessment of the prognostic value of the classification. Thus, validation of the classification is not yet completed.

In conclusion, the PCCF is a comprehensive classification system for long bone fractures of the upper extremity. It can easily be used routinely in clinics, assisted by the AOCOIAC software. Further prospective clinical studies are required to fully validate the PCCF and to determine its clinical relevance in terms of support for treatment decisions and prognostication of outcome.

Supplementary data

Tables 3–7 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2016.1258532.

AJ collected all the clinical data from the Children’s Hospital in Bern and was involved in overall data analysis and interpretation. He provided input for all manuscript drafts. NL collected all the clinical data from the Children’s Hospital in Lausanne, contributed to data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript. AB reviewed all data, prepared the first draft of the manuscript, and did the final copy editing and formatting. TS was the initiator of the development of the PCCF and AOCOIAC. He was involved in data analysis and interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. LA was an employee of AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation (AOCID) at the time of data collection and most of the analyses, and the overall project methodologist and coordinator included in the development and introduction of AOCOIAC in the participating clinics. He was the mentor of AJ during his fellowship at AOCID and supervised this project. He performed the majority of data analyses, and participated in preparation of the manuscript.

This investigation was performed with the support of the AO Foundation via the AO Trauma Network. We thank Anahi Hurtado (AOCID) for her scientific input.

AJ and AB are employed by AOCID, an institute of the AO Foundation, which is a medically guided not-for-profit foundation. LA declares consultancy payments from AOCID for the completion of this manuscript. NL and TS have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary Material

References

- Audigé L, Hunter J, Weinberg A, Magidson J, Slongo T.. Development and evaluation process of a paediatric long-bone fracture classification proposal. European Journal of Trauma 2004; 30 (4): 248–54. [Google Scholar]

- Audige L, Bhandari M, Hanson B, Kellam J.. A concept for the validation of fracture classifications. J Orthop Trauma 2005; 19 (6): 401–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audige L, Cornelius C P, Kunz C, Buitrago-Tellez C H, Prein J.. The Comprehensive AOCMF Classification System: classification and documentation within AOCOIAC Software. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr 2014; 7 (Suppl 1): S114–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audigé L, Slongo T, Lutz N, Blumenthal A, Joeris A.. The AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF). Part III: Multifragmentary long bone fractures in children—a retrospective analysis of 2716 patients from 2 Swiss tertiary pediatric hospitals. Acta Orthop 2016.[Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- Bado J L. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967; 50: 71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J H, DeLuca S A.. Growth plate injuries: Salter-Harris classification. Am Fam Physician 1992; 46 (4): 1180–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson S, Woolridge D P, Colletti J, Kilgore K.. Pediatric upper extremity injuries. Pediatr Clin North Am 2006; 53 (1): 41–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J C, Shen W Y.. Limb fracture pattern in different pediatric age groups: a study of 3,350 children. J Orthop Trauma 1993; 7 (1): 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart E S, Grottkau B E, Rebello G N, Albright M B.. Broken bones: common pediatric upper extremity fractures–part II. Orthop Nurs 2006; 25 (5): 311–23; quiz 24-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joeris A, Lutz N, Blumenthal A, Slongo T, Audigé L.. The AO Pediatric Comprehensive Classification of Long Bone Fractures (PCCF). Part II: Location and Morphology of 548 Lower Extremity Fractures in Children and Adolescents. Acta Orthop 2016. [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- Joeris A, Lutz N, Wicki B, Slongo T, Audige L.. An epidemiological evaluation of pediatric long bone fractures - a retrospective cohort study of 2716 patients from two Swiss tertiary pediatric hospitals. BMC Pediatr 2014; 14: 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphaus A, Rapp M, Wessel L M, Buchholz M, Massalme E, Schneidmuller D, Roeder C, Kaiser M M.. [LiLa classification for paediatric long bone fractures. Intraobserver and interobserver reliability]. Unfallchirurg 2015; 118 (4): 326–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus R, Wessel L.. The treatment of upper limb fractures in children and adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107 (51-52): 903–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landfried M J, Stenclik M, Susi J G.. Variant of Galeazzi fracture-dislocation in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1991; 11 (3): 332–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landin L A. Fracture patterns in children. Analysis of 8,682 fractures with special reference to incidence, etiology and secular changes in a Swedish urban population 1950-1979. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1983; 202: 1–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann D C, Rajmaira S.. Distribution of physeal and nonphyseal fractures in 2,650 long-bone fractures in children aged 0-16 years. J Pediatr Orthop 1990; 10 (6): 713–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J S, Marsh J L.. Current classification of fractures. Rationale and utility. Radiol Clin North Am 1997; 35 (3): 491–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meling T, Harboe K, Soreide K.. Incidence of traumatic long-bone fractures requiring in-hospital management: a prospective age- and gender-specific analysis of 4890 fractures. Injury 2009; 40 (11): 1212–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M E, Nazarian S, Koch P, Schatzker J.. The Comprehensive Classification of Fractures of Long Bones. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, London, Paris, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Barcelona: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden J A. Injury to the growth mechanisms of the immature skeleton. Skeletal Radiol 1981; 6 (4): 237–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson H A. Physeal fractures: Part 2. Two previously unclassified types. J Pediatr Orthop 1994a; 14 (4): 431–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson H A. Physeal fractures: Part 3. Classification . J Pediatr Orthop 1994b; 14 (4): 439–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson H A, Madhok R, Benson J T, Ilstrup D M, Melton L J 3rd.. Physeal fractures: Part 1. Epidemiology in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979-1988. J Pediatr Orthop 1994; 14 (4): 423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salter R B, Harris W R.. Injuries Involving the Epiphyseal Plate. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1963; 45-A (3): 587–622. [Google Scholar]

- Schalamon J, Dampf S, Singer G, Ainoedhofer H, Petnehazy T, Hoellwarth M E, Saxena A K.. Evaluation of fractures in children and adolescents in a Level I Trauma Center in Austria. J Trauma 2011; 71 (2): E19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sferopoulos N K. Classification of distal radius physeal fractures not included in the salter-harris system. Open Orthop J 2014; 8: 219–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slongo T, Audige L, Schlickewei W, Clavert J M, Hunter J, International Association for Pediatric Traumatology. Development and validation of the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures by the Pediatric Expert Group of the AO Foundation in collaboration with AO Clinical Investigation and Documentation and the International Association for Pediatric Traumatology. J Pediatr Orthop 2006; 26 (1): 43–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slongo T, Audige L, Clavert J M, Lutz N, Frick S, Hunter J.. The AO comprehensive classification of pediatric long-bone fractures: a web-based multicenter agreement study. J Pediatr Orthop 2007a; 27 (2): 171–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slongo T F, Audige L, Group A O P C. . Fracture and dislocation classification compendium for children: the AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF). J Orthop Trauma 2007b; 21 (10 Suppl): S135–S60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slongo T, Audige L, Lutz N, Frick S, Schmittenbecher P, Hunter J, Clavert J M.. Documentation of fracture severity with the AO classification of pediatric long-bone fractures. Acta Orthop 2007c; 78 (2): 247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley E A, de Ia Garza J F.. Monteggia fracturedislocation in children In: Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. (Ed. Beaty JH, Kasser JR). Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Waters P M. Distal radius and ulna fractures In: Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. (Ed. Beaty JH, Kasser JR). Lippincott-Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.