Abstract

Background and purpose

Little is know about patterns of sick leave in connection with total hip and knee joint replacement (THR and TKR) in patients with osteoarthritis (OA).

Patients and methods

Using registers from southern Sweden, we identified hip and knee OA patients aged 40–59 years who had a THR or TKR in the period 2004–2012. Patients who died or started on disability pension were excluded. We included 1,307 patients with THR (46% women) and 996 patients with TKR (56% women). For the period 1 year before until 2 years after the surgery, we linked individual-level data on sick leave from the Swedish Social Insurance Agency. We created a matched reference cohort from the general population by age, birth year, and area of residence (THR: n = 4,604; TKR: n = 3,425). The mean number of days on sick leave and the proportion (%) on sick leave 12 and 24 months before and after surgery were calculated.

Results

The month after surgery, about 90% of patients in both cohorts were on sick leave. At the two-year follow-up, sick leave was lower for both cohorts than 1 year before surgery, except for men with THR, but about 9% of the THR patients and 12–17% of the TKR patients were still sick-listed. In the matched reference cohorts, sick leave was constant at around 4–7% during the entire study period.

Interpretation

A long period of sick leave is common after total joint replacement, especially after TKR. There is a need for better knowledge on how workplace adjustments and rehabilitation can facilitate the return to work and can postpone surgery.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common reasons for chronic musculoskeletal pain (Arden and Nevitt 2006, Vos et al. 2012). OA is among the top 10 disabling diseases in the western world (OECD 2013). It is not only a disease of the elderly, but also affects the working-age population. In Sweden, where we conducted this study, the prevalence of doctor-diagnosed hip OA and knee OA in individuals aged 45 years or more has been reported to be 6% and 14%, respectively (Turkiewicz et al. 2014a,b). During the progression of OA, pain—both during activity and at rest—often occurs more frequently and with increased intensity. This may cause both loss of work productivity (presenteeism) and sick leave (absenteeism). Indeed, women with knee OA have an almost doubled risk of sick leave in comparison to a general population (Hubertsson et al. 2013).

With severe OA, a total hip replacement (THR) or total knee replacement (TKR) may be necessary to obtain sufficient pain relief, and to improve physical function and maintain the same activity level (Zhang et al. 2012, McAlindon et al. 2014). The number of patients who have a THR or a TKR is steadily increasing (Losina et al. 2012). The same trend is apparent in all OECD countries (OECD 2013). Still, we know very little about the patterns of sick leave (as a measure of absenteeism) before and after joint replacement surgery. Thus, we determined how hip and knee OA patients are sick-listed before and after a THR or TKR using individual-level data from an entire geographic region. We also related the sick leave to the level of sick leave in the general population.

Patients and methods

Study design

We conducted an observational study on patients with hip OA and knee OA who had had a THR or a TKR. The setting was the Skåne region in southern Sweden. The region is one of the largest counties in Sweden and contains both rural and urban areas. The population of 1,274,069 inhabitants (2013) accounts for approximately one-eighth of the Swedish population. We crosslinked data at the individual level from 2 registers using the Swedish 10-digit personal identification number.

The Skåne Healthcare Register (SHR)

Healthcare in Sweden is financed by taxes, and all healthcare providers (both public and private) must register each consultation using the patient’s unique personal identification number. Each single healthcare consultation generates data that are transferred to a central database (the SHR). Since 1997, diagnoses have been classified according to the Swedish translation of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 10 system (WHO, 2015), and surgical codes are classified according to the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures (NCSP 96).

The Swedish Social Insurance Agency

According to Swedish legislation, all residents aged 16 to 64 years are insured by the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SSIA) and can be granted economic security if the ability to work is limited by least 25% due to sickness, disability, or injury (Borg et al. 2006). Different forms of benefits are sick leave, sick leave in prevention, sick leave for rehabilitation, and also—when having more permanent work disability—sickness compensation. The first day that sickness is reported is a qualifying day where no compensation is provided. The 13 days that follow are compensated for by the employer, at a slightly lower level than the ordinary salary. After this, the benefits are paid by the SSIA. Thus, sick periods of 14 days or shorter are therefore not registered by the SSIA, except for students and unemployed individuals.

Sick leave compensation can be provided as full, three-quarters, half, or one-quarter benefit depending on the limitation in work ability. From the eighth day reporting sick, a doctor’s certificate is required, to verify the need for sick leave. Sickness compensation (before 2003, referred to as disability pension) can be granted to insured individuals with a permanent or long-term (at least 1 year) full or partial work disability, based on a medical condition due to illness or injury. Sickness compensation is payable as full, three-quarters, half, or one-quarter benefit, depending on the extent of the reduction in work ability. In the present study, sick leave is defined as days with sickness benefit registered at the SSIA. Patients with sickness compensation were not included in this study.

Patient cohorts

Using ICD-10 codes, we identified all patients diagnosed with hip OA (M16) who had a THR (surgical code NFB49), and all patients diagnosed with knee OA (M17) who had a TKR (surgical code NGB49), registered in the SHR during the period January 2004 to December 2012. The first time the surgical code (NFB49 or NGB49) appeared (date of surgery) was selected as day 0. For them to be eligible for the study, we also required that all patients to be included were resident in the Skåne region 1 year before surgery, and that they were 40–59 years old at the time of surgery. Subjects who died or received disability pension/sickness compensation were excluded. For each patient, we linked data from the SSIA on sick leave for the period of 360 days before the date of surgery and up to a maximum of 719 days after the date of surgery. We created 2 different cohorts, 1 for THR patients and 1 for TKR patients.

Reference cohorts

A reference cohort was identified for each of the 2 patient cohorts, by random sampling of matched subjects (with a case-reference ratio of 1:4) who had had any kind of healthcare contact that was registered in the SHR during the period 2004–2012. The matching variables were same sex, same year of birth, and same area of residence. Day 0 was set to be the day corresponding to the day of TKR/THR for the joint replacement patients. In line with the 2 case cohorts, subjects in the reference cohorts who died or received any kind of disability pension/sickness compensation during the study period were excluded.

Statistics

The month of the THR or TKR was set as month 0 (surgery month) for the THR and TKR cohorts and for the reference cohorts. Based on all patients who were on any type of sick leave in a particular month, we calculated mean number of days of sick leave with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for each month, and for each cohort. 2 half-days on sick leave were counted as 1. For each cohort (THR or TKR), we calculated the proportion of patients with sick leave in 30-day intervals from 360 days before until 719 days after day 0. When calculating the proportion of individuals on sick leave, subjects with any ongoing sick leave during that particular month (irrespective of extent) were counted to the nominator. We also calculated the length of the sick leave periods that started around surgery (on day 7 before surgery or later) in patients in both cohorts (THR/TKR) who had had no ongoing sick leave on day 30 to day 8 before surgery.

Ethics

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Lund University (entry no. 301-2007).

Results

THR and reference cohort—characteristics

We identified 1,581 working-age THR patients. After exclusion of 274 patients, the final THR cohort had 1,307 individuals (Table 1). There were more men (54%) than women (46%) in the final THR cohort, but there was no statistically significant difference in mean age relative to the original cohort. Mean age was 53 (SD 5.0) years in women and 53 (SD 5.1) years in men. Of the individuals who were excluded, there were more women (69%) than men (31%), and the mean age was 54 (SD 4.7) years in women and 54 (SD 5.1) years in men. The reference cohort had 4,604 individuals, after exclusion of 1,702. There were more men (56%) than women (44%) in the reference cohort also, with a mean age for both men and women of 53 (SD 5.1) years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients who underwent total hip replacement (THR) or total knee replacement (TKR), and their reference cohorts

| THR n = 1,307 |

THR reference cohort n = 4,604 |

TKR n = 996 |

TKR reference cohort n = 3,425 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n (%) | 712 (54) | 2,572 (56) | 433 (44) | 1,543 (45) |

| Women, n (%) | 595 (46) | 2,032 (44) | 563 (56) | 1,882 (55) |

| Mean age (SD) | ||||

| All | 53 (5.1) | 53 (5.1) | 55 (3.9) | 55 (3.9) |

| Men | 53 (5.1) | 53 (5.1) | 53 (3.9) | 55 (4.0) |

| women | 53 (5.0) | 53 (5.1) | 53 (3.8) | 55 (3.9) |

TKR and reference cohort—characteristics

1,296 TKR patients were identified. We then excluded 300 patients and the TKR cohort ended up with 996 patients, of whom 563 were women (56%) and 433 were men (44%) (Table 1). The sex distribution differed from that of the group that was excluded (78% women and 22% men). In the TKR cohort, both women and men had a mean age of 55 (SD 3.8 and 3.9) years, and this was not significantly different from the group of patients who were excluded, where women had a mean age of 55 (SD 3.9) years and men 56 (SD 3.1) years.

A reference population of 5,146 individuals was identified and 1,721 individuals were excluded. In the final reference population (n = 3,425), 55% were women and 45% were men. There was no significant difference in mean age compared to the TKR cohort.

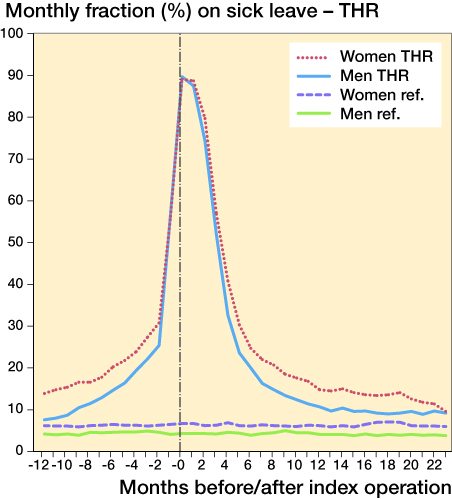

Sick leave in the THR cohort and the corresponding reference population

At month 12 before THR, more women (14%) than men (8%) were on sick leave (Figure 1). In relation to the matched reference individuals, more hip OA patients were on sick leave throughout the entire study period. This was apparent already at 1 year before surgery, but also 2 years after surgery. Close to the time of surgery when sick leave peaked, the proportion of women and men who were sick-listed was similar (89% and 90%, respectively), but during the postoperative period, women generally had a slightly delayed return to work compared to men (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patterns of sick leave (percentage on sick leave during a particular month) in men and women who underwent total hip replacement (THR) and their reference cohort.

The mean number of days on sick leave was equally distributed among men and women in the month after surgery and at 2-year follow-up. In relation to the reference population, both men and women had more days on sick leave 1 year before surgery, in the month of surgery, and at 2-year follow-up (Table 2). For THR patients who started a new episode of sick leave from day 7 before surgery and who had had no ongoing sick leave from day 30 to day 8 before surgery (n = 698), the median postoperative sick leave period in women lasted for 89 (IQR: 69–124) full days and in men it lasted for 88 (IQR: 61–110) full days.

Table 2.

Mean number of days of sick leave (95% CI) per month in men and women who underwent THR, and in their reference population

| THR |

Reference population |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 712 |

Women n = 595 |

Men n = 2,572 |

Women n = 2,032 |

|

| Months before THR | ||||

| 12 | 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | 2.9 (2.3–3.4) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 6 | 3.1 (2.6–3.6) | 4.2 (3.6–4.9) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| 3 | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 5.9 (5.1–6.6) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| Month of surgery | 26.4 (25.8–26.9) | 26.3 (25.6–26.9) | 0.9 (0.8–1.1) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

| Months after THR | ||||

| 3 | 10.4 (9.6–11.2) | 11.9 (11.1–12.8) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| 6 | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 5.1 (4.5–5.8) | 0.8 (0.7–0.9) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 12 | 2.4 (1.9–2.9) | 3.1 (2.5–3.6) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| 18 | 1.9 (1.5–2.3) | 2.8 (2.3–3.3) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | 1.5 (1.3–1.7) |

| 24 | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 2.0 (1.5–2.4) | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

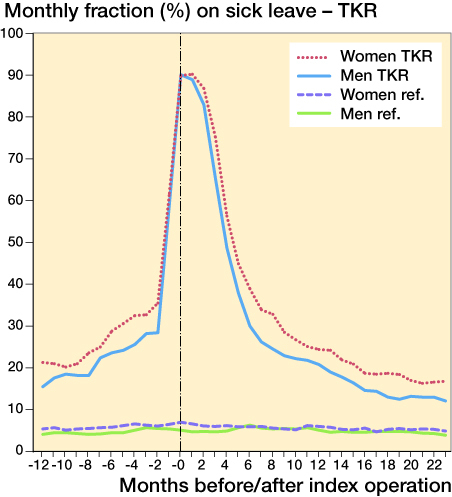

Sick leave in the TKR cohort and the corresponding reference population

1 year before TKR, 21% of the women were on sick leave (Figure 2) and in the month of surgery, 90% were on sick leave. After surgery, sick leave decreased and 2 years after TKR, 17% of the women were still on sick leave. In men, 16% were on sick leave 1 year before TKR and in the month of surgery, 90% were sick-listed. Sick leave decreased during the 2-year follow-up, but 12% of men were still sick-listed 2 years after TKR. In comparison to the reference population, a greater proportion of both men and women who underwent TKR were on sick leave during the entire period (Figure 2). The mean number of days on sick leave were higher in both men and women in the TKR cohort 1 year before TKR, in the month of surgery, and 2 years after TKR, compared to the reference population (Table 3). Mean number of days on sick leave were slightly lower 2 years after surgery than 1 year before. Regarding the patients who started a new episode of sick leave in connection with surgery (from day 7 before TKR) and had had no ongoing sick leave from day 30 to day 8 before surgery (n = 493), the median period of sick leave was 117 (IQR: 90–183) full days for women and 96 (IQR: 82–153) full days for men.

Figure 2.

Patterns of sick leave (percentage on sick leave during a particular month) in men and women who underwent total knee replacement (TKR) and their reference cohort.

Table 3.

Mean number of days of sick leave (95% CI) per month in men and women who underwent TKR, and in their reference population

| TKR |

Reference population |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men n = 433 |

Women n = 563 |

Men n = 1,543 |

Women n = 1,882 |

|

| Months before TKR | ||||

| 12 | 3.5 (2.8–4.3) | 4.4 (3.8–5.1) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 6 | 5.3 (4.5–6.1) | 6.2 (5.5–7.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) |

| 3 | 6.8 (5.9–7.7) | 7.6 (6.8–8.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 1.4 (1.1–1.6) |

| Month of surgery | 26.5 (25.8–27.3) | 26.6 (26.0–27.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.4 (1.2–1.6) |

| Months after TKR | ||||

| 3 | 14.8 (13.8–15.9) | 16.9 (16.0–17.8) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) |

| 6 | 6.9 (5.9–7.8) | 7.9 (7.1–8.7) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| 12 | 4.9 (4.1–5.8) | 5.2 (4.5–5.9) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) |

| 18 | 3.1 (2.4–3.8) | 3.7 (3.1–4.4) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) |

| 24 | 2.8 (2.1–3.4) | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

Discussion

We have determined the patterns of sick leave before and after total hip or knee joint replacement in Sweden. Compared to our reference cohorts, patients who underwent THR or TKR had more sick leave during the entire study period. This can be interpreted as hip and knee OA having a substantial impact on patients’ work participation over an extended period of time. This is in line with a recent study on determinants of return to work by Leichtenberg et al. (2016). Interestingly, patients who undergo TKR have more sick leave in the year before surgery than patients who undergo THR, and they also have a slower return to work. Women generally have more sick leave before surgery and a slower return to work after both THR and TKR.

Total joint replacement is an effective treatment for severe joint pain and disability due to hip and knee OA. Patient education programs are recommended for OA patients with mild to moderate OA, but they can also be beneficial before surgery (Villadsen et al. 2014). Skou et al. (2015) compared TKR in combination with a 12-week patient education program with the patient education program only (nonoperative treatment), and found that surgery was favorable concerning the degree of pain relief and functional improvements at 12-month follow-up. However, it is important to notice that the group that was treated nonoperatively also showed substantial improvement, such as a clinically relevant increase in health-related quality of life. Furthermore, surgery was associated with 4 times the number of serious adverse events compared to nonoperative treatment. Kleim et al. (2015) have suggested that offering a THR/TKR at an earlier stage might limit the loss of work ability, but in the trial by Skou et al. (2015) only 26% of the patients who did not undergo surgery actually had a TKR within the 1-year follow-up period. This highlights the importance of discussing the relative advantages or disadvantages of surgery compared to nonoperative treatment options.

There is very little literature on how return to work can be facilitated after THR/TKR (Kuijer et al. 2009). Individuals who have been employed before surgery (Tilbury et al. 2014) or who have had no previous sick leave (Kleim et al. 2015, Kuijer et al. 2016, Leichtenberg et al. 2016) have been found to be more likely to return to work. In our study, around half of the patients started the episode of sick leave close to surgery and had had no heavy burden of sick leave before surgery. We have no information on why these patients were less sick-listed. There could be several reasons such as better general health, psychosocial factors, less demanding work, better possibility of making adjustments at work or of changing work tasks. Wilkie and Pransky (2012) concluded that it is important to involve the employer in the return to work process. This calls for a closer collaboration between patient, healthcare system, and employer, in order to arrange for a sustainable return to work. A safe return to work can often be ensured by awareness of modifiable risk factors (Leichtenberg et al. 2016).

We corroborate previous findings that postoperative results regarding work performance are better for THR than for TKR (Kleim et al. 2015). The results of a systematic review (2011) suggested that individuals with hip and knee OA generally manage to stay at work (Bieleman et al. 2011). However, it is important to identify individuals who are at risk of developing work disability due to OA at an early stage, to prevent early retirement (Wilkie et al. 2014).

When identifying the study cohorts, subjects with sickness compensation/disability pension were excluded. In both the THR and TKR cohort, in the subjects who were excluded there was a higher proportion of women (69% and 78%, respectively). This may indicate that women with hip or knee OA receive sickness compensation to a greater degree than men. Since there are differences in how women and men are employed on the labor market, and consequently how they are exposed for different risk factors at work, further attention should be payed to this question.

Hip and knee OA is associated with heavy workload (Andersen et al. 2012). Knee-demanding work, such as kneeling and squatting, is associated with knee OA (Klussman et al. 2010) and a slower return to work (Kuijer et al. 2016). The prevalence of hip OA is reported to be higher in farmers (Thelin and Holmberg 2007), and men in occupations with a heavy workload have an increased risk of requiring a THR (Rubak et al. 2013, 2014)—and also of having a slower return to work (Kleim et al. 2015). In men especially, a heavy work load is associated with an increased risk of both THR and TKR (Franklin et al. 2010). In this study, we did not have information on patient employment before or after surgery, whether present or previous. This would have been important information, and the lack of it may also have had a confounding effect on the results. We also lacked information on whether the patient returned to the same workplace and the same occupation as before surgery, and whether any adjustments to the workplace had been carried out.

We studied all-cause sick leave. Thus, we do not know whether individuals were sick-listed for reasons other than their hip or knee OA. Comorbid conditions will of course have an influence on sick leave (Carstensen et al. 2012, Jämsen et al. 2013).

We conclude that patients who undergo THR or TKR are sick-listed to a much greater extent than the general population, both before and after surgery. Since a substantial part of knee and hip OA patients are of working age (Turkiewicz et al. 2014a,b), it is important to not only focus on sick leave but also on presenteeism, which has a substantial influence on work productivity (Hermans et al. 2012, Kingsbury et al. 2014). There is a need for more knowledge regarding whether different types of interventions, such as patient education programs and/or adjustments to the workplace, can prohibit or delay surgery—or facilitate a faster return to work. Long-term prospective health economy studies should be undertaken, which focus on the cost to society of alternative treatments, in addition to joint replacement.

KS interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. ME designed the study, interpreted the results, and revised the manuscript. CZ performed data management, did the analyses, and revised the manuscript. LD, IP, and HL interpreted the results and revised the manuscript.

We thank the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Sweden, for financial support.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the King Gustaf V 80-Year Birthday Fund, the Kock Foundations, the Faculty of Medicine of Lund University, governmental funding of clinical research within National Health Service (ALF), and Region Skåne. The sources of funding had no influence on the study design; on collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- Andersen S, Thygesen L C, Davidsen M, Helweg-Larsen K.. Cumulative years in occupation and the risk of hip or knee osteoarthritis in men and women: a register-based follow-up study. Occup Environ Med 2012; 69(5): 325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arden N, Nevitt M C.. Osteoarthritis: epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2006; 20(1): 3–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieleman H J, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Oosterveld F G, Reneman M F, Verhagen A P, Groothoff J W.. The effect of osteoarthritis of hip or knee on work participation. J Rheumatol 2011; 38(9): 1835–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg K, Goine H, Söderberg E, Marnetoft S U, Alexanderson K.. Comparison of seven measures of sickness absence based on data from three counties in Sweden. Work 2006; 26(4): 421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen J, Andersson D, André M, Engström S, Magnusson H, Borgquist L A.. How does comorbidity influence healthcare costs? A population-based cross-sectional study of depression, back pain and osteoarthritis. BMJ Open 2012; 25: 2(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin J, Ingvarsson T, Englund M, Lohmander S.. Association between occupation and knee and hip replacement due to osteoarthritis: a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12(3): R102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans J, Koopmanschap M A, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, van Linge J H, Verhaar J A N, Reijman M, Burdorf A.. Productivity costs and medical costs among working patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012; 64(6): 853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubertsson J, Petersson IF, Thorstensson C A, Englund M.. Risk of sick leave and disability pension in working-age women and men with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72(3): 401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jämsen E, Peltola M, Eskelinen A, Letho M U.. Comorbid diseases as predictor of survival of primary total hip and knee replacements: a nationwide register-based study of 96,754 operations on patients with primary osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72(12): 1975–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury S R, Gross HJ, Isherwood G, Conaghan P G.. Osteoarthritis in Europe: impact on health status, work productivity and use of pharmacotherapies in five European countries. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014; 53(5): 937–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleim B D, Malviya A, Rushton S, Bardgett M, Deehan D J.. Understanding the patient-reported factors determining time taken to return to work after hip and knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23(12): 3646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klussman A, Gebhardt H, Nübling M, Liebers F, Quirós Perea E, Cordier W, von Engelhardt L V, Schubert M, Dávid A, Bouillon B, Rieger M A.. Individual and occupational risk factors for knee osteoarthritis: results of a case-control study in Germany. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12(3): R88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijer P P, de Beer M J, Houdijk J H, Frings-Dresen M H.. Beneficial and limiting factors affecting return to work after total knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil 2009; 19(4): 375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijer P P F M, Kievit A J, Pahlplatz T M J, Hooiveld T, Hoozemans M J M, Blankevoort L, Schafroth MU, van Geenen R C I, Frings-Dresen M H W.. Which patients do not return to work after total knee arthroplasty? Rheumatol Int 2016; 36(9): 1249–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichtenberg C S, Tilbury C, Kuijer P P F M, Verdegall S H M, Wolterbeek R, Nelissen R G H H, Frings-Dresen M H W, Vliet Vlieland T P N.. Determinants of return to work 12 month after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2016; 98(6): 387–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losina E, Thornhill T S, Rome B N, Wright J, Katz J N.. The dramatic increase in total knee replacement utilazation rates in the United States cannot be fully explained by growth in population size and the obesity epidemic. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(3): 201–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlindon T E, Bannuru R R, Sullivan M C, Arden K K, Berenbaum F, Bierma-Zeinstra S M, Hawker SA, Henrotin Y, Hunter D J, Kawaguchi H, Kwoh K, Lohmander S, Rannou F, Roos E, Underwood M.. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014; 22(3): 363–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Health at a glance 2013. OECD indicators. Cited: 2015-11-20. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rubak T S, Svendsen S W, Søballe K, Frost P.. Risk and rate advancement periods of total hip replacement due to primary osteoarthritis in relation to cumulative physical workload. Scand J Work Environ Health 2013; 39(5): 486–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak T S, Svendsen S W, Søballe K, Frost P.. Total hip replacement due to primary osteoarthritis in relation to cumulative occupational exposures and lifestyle factors: a nationwide nested case-control study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014; 66(10): 1496–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skou S T, Roos E M, Laursen M B, Rathleff M S, Arednt-Nielsen L, Simonsen O, Rasmussen S.. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1597–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelin A, Holmberg S.. Hip osteoarthritis in a rural male population: A prospective population-based register study. Am J Ind Med 2007; 50(8): 604–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbury C, Schaasberg W, Plevier J W, Fiocco M, Nelissen R G, Vliet Vlieland T P.. Return to work after total hip and knee artopasty: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2014; 53(3): 512–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiewicz A, Gerhardsson De Verdier M, Enström G, Nilsson P M, Mellström C, Lohmander L S, Englund M.. Prevalence of knee pain and knee OA in southern Sweden and the proportion that seeks medical care. Rheumathology (Oxford) 2014a; 54(5): 827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkiewicz A, Petersson IF, Björk J, Hawker G, Dahlberg LE, Lohmander LS, Englund M.. Current and future impact of osteoarthritis on health care: a population-based study with projections to year 2032. Osteoartritis Cartilage 2014b; 22(11): 1826–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villadsen A, Overgaard S, Holsgaard-Larsen A, Christensen R, Roos E M.. Post-operative effect of neuromuscular exercise prior to hip or knee arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73(6): 1130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T, Flaxman A D, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 disease and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380(9859): 2163–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie R, Pransky G.. Improving work participation for adults with musculoskeletal conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012; 26(5): 733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie R, Philipson C, Hay E M, Pransky G.. Anticipated significant work limitation in primary care consulters with osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2014; 4(9): e005221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases and related health problems. Version 10. Available at: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/index.html. Cited: 2015-01-30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz R W, Abramson S, Altman R D, Arden N, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Brandt K D, Croft P, Doherty M, Dougados M, Hochberg M, Hunter DJ, Kwoh K, Lohmander L S, Tugwell P.. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 18(4): 476–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]