Abstract

Background and purpose

Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has been used in recent years in the hope of improving the alignment and positioning of the implant, thereby achieving a better functional outcome and durability. However, the role of computer navigation in TKA is still under debate. We used radiostereometric analysis (RSA) in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine whether there are any differences in migration of the tibial component between CAS- and conventionally (CONV-) operated TKA.

Patients and methods

54 patients (CAS, n = 26; CONV, n = 28) with a mean age of 67 (56–78) years and with osteoarthritis or arthritic disease of the knee were recruited from 4 hospitals during the period 2009–2011. To estimate the mechanical stability of the tibial component, the patients were examined with RSA up to 24 months after operation. The following parameters representing tibial component micromotion were measured: 3-D vector of the prosthetic marker that moved the most, representing the magnitude of migration (maximum total point motion, MTPM); the largest negative value for y-translation (subsidence); the largest positive y-translation (lift-off); and prosthetic rotations. The precision of the RSA measurements was evaluated and migration in the 2 groups was compared.

Results

Both groups had most migration within the first 3 months, but there was no statistically significant difference in the magnitude of the migration between the CAS group and the CONV group. From 3 to 24 months, the MTPM (in mm) was 0.058 and 0.103 (p = 0.1) for the CAS and CON groups, respectively, and the subsidence (in mm) was 0.005 and 0.011 (p = 0.3).

Interpretation

Mean MTPM, subsidence, lift-off, and rotational movement of tibial trays were similar in CAS- and CONV-operated knees.

Computer navigation has been used over the past decade in TKA, in the hope of improving the alignment and positioning of the implant and acheiving a better functional outcome, less loosening, and a reduced need for revision (Bauwens et al. 2007, Spencer et al. 2007, Kim et al. 2009, Longstaff et al. 2009, Lad et al. 2013, Lützner et al. 2013, Dyrhovden et al. 2013, Blakeney et al. 2011, 2014, Gøthesen at al. 2014). Several authors have reported improved alignment and better component positioning with computer-assisted surgery (CAS) (Chauhan et al. 2004, Lüring et al. 2006, Dyrhovden et al. 2013, Gøthesen at al. 2014, Lad et al. 2013, Cip et al. 2014), but the role of computer navigation in TKA is still under debate (Gøthesen et al. 2014, de Steiger et al. 2015).

One meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) has concluded that CAS does improve the mechanical leg axis and component orientation in TKA (Cheng et al. 2012). Another meta-analysis by Shi et al. (2014) found fewer outliers when comparing mechanical axis in the CAS group to that in the CONV group, but this was not statistically significant. The operation time was 17 min longer in the CAS group, and there were fewer complications observed in patients who were operated with CAS.

It is known that alignment is important for good clinical results and longevity (Ritter et al. 1994, Fehring et al. 2001). Choong et al. (2009) concluded in their study that neutral alignment correlates with good function. They suggested that this correlation was due to the use of CAS. However, they did not compare CAS with CONV, but rather, well-aligned TKA with malaligned TKA. Based on other studies, however, it remains controversial whether improved alignment, as obtained by CAS, gives better function (Bauwens et al. 2007, Kim et al. 2009, Longstaff et al. 2009, Gøthesen et al. 2014) or longevity of TKA (Parratte et al. 2010). To make this issue even more complex, some researchers question the aim of neutral alignment in all knees following TKA (Bellemans 2011).

In a registry-based study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty registry (NAR) (Gøthesen et al. 2011), the main conclusion was that the short-term risk of revision was either the same or increased for CAS, and depended on the brand of prosthesis. The use of CAS in Norway peaked at 21% in 2008, but declined to 8% in 2015 (NAR 2015). In another study, from the Australian registry (AOA), CAS was found to reduce the overall rate of revision as well as the rate of revision for loosening/lysis in patients less than 65 years of age (de Steiger et al. 2015). In Australia, the use of CAS increased from about 3% in 2004 to 27% in 2014 (AOA 2015).

Radiostereometric analysis (RSA) can be used to evaluate migration of arthroplasty implants in the bone with high precision. Implants that migrate more than a certain limit within 1 or 2 years are at risk of aseptic loosening at a later stage. Thus, RSA findings can be used to predict mechanical loosening of knee prostheses (Nilsson et at. 1991, Ryd et al. 1995, Valstar et al. 2005, Kärrholm et al. 2006). The initial migration, mostly occurring during the first 3 months, probably represents both bone remodeling and creep of the plastic component. Thereafter, there is a clear association between early migration, expressed as MTPM at 1 year, and the 5-year revision rate (Ryd et al. 1995, Pijls et al. 2012). The use of a migration limit of 2 mm at 2 years indicated that revision due to loosening could be predicted with a sensitivity of 58% and a specificity of 93% (Ryd et al. 1995). Pijls et al. (2012) found that for every mm increase in migration at 1 year, there was an 8% increase in revision rate at 5 years.

To our knowledge, there has been only 1 published RCT using RSA analysis to compare CT-free and CT-based CAS-operated TKA (van Strien et al. 2009). These authors also matched the CAS-operated patients from the RCT and 21 TKAs with RSA markers from another study and compared the 2 groups. The main finding was that there was more subsidence of the tibial component in the CONV group than in both CAS groups at 2-year follow-up. There was, however, no significant difference in alignment between CAS- and CONV-operated TKA.

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether there are any differences between CAS- and CONV-operated TKA in terms of early migration. Repeated RSA examinations during the first 2 postoperative years were performed to measure implant migration.

Patients and methods

This RSA study was part of a larger RCT investigating clinical and radiological outcome after total knee replacement operated with either CAS or CONV technique (Gøthesen et al. 2014).

192 patients were included in the trial, allocated randomly to CAS (n = 97) or CONV (n = 95). The first 54 patients operated were marked with RSA markers.

Patients were randomly parallel-assigned to either CAS or CONV (allocation ratio: 1:1). Due to the slow recruitment rate, the age criteria for inclusion were changed after 6 months, from 60–80 years to 50–85 years. Ultimately, eligible patients were men and women 50–85 years of age who were in need of a TKA, with primary, secondary, or inflammatory arthritis of the knee and with ASA category 1–3.

Exclusion criteria included severe systemic disease, severe neurological disorder, a history of cancer, dementia, BMI >35, previous fractures of the shaft of the tibia or femur, severe preoperative valgus position of the knee (> 15° from the mechanical axis of the knee), previous osteotomy of the tibia or femur, knee injury less than a year preoperatively, severe stiffness of the ipsilateral hip, ipsilateral hip replacement, and allergy to metals. For patients with bilateral knee replacements, only the first knee evaluated in the recruitment period was included in the trial.

The recruitment period was 2009–2011, and patients were identified in 4 orthopedic clinics in Norway. 8 surgeons performed the knee replacements. They were all experienced in TKA (defined as having performed >100 CONV procedures), and each surgeon had carried out at least 10 TKAs using CAS before recruiting patients into the trial. We used a block randomization method in order to ensure that each surgeon operated an equal number of patients in each of the 2 study groups.

The trial was designed and conducted according to the CONSORT statement guidelines for reporting of parallel-group randomized trials (Schulz et al. 2010).

Intervention

A cemented cruciate retaining (CR) Profix total knee prosthesis (Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN) was implanted in all patients using Palacos R + G cement (Heraeus, Hanau, Germany). We used keeled implants in all patients with tibia size 3 or more; smaller sizes had a 5-cm metaphyseal stem (Table 1). We used the “measured bone resection” femur first technique (Whiteside and Arima 1995,Dennis et al. 2010) in all cases, and the principles of TKA and ligament balancing according to Whiteside (2002) were applied. No patellar resurfacing was performed. The tibial component was implanted with a view to achieving a 4° posterior slope and neutral alignment in the frontal plane. In the CONV group, conventional instruments and intramedullary rods were used, both in the femur and tibia. The femoral component was inserted in neutral alignment in the frontal plane (referring to the mechanical axis, the surgeon could choose between 5° and 7° valgus cutting blocks with reference to the intramedullary rod) and the sagittal plane (referring to the anatomical axis), or optionally with 4° flexion of the femoral component. In the CAS group, neutral alignment was aimed for in the frontal plane, and an individualized flexion of the femoral component and 4° slope of the tibia was allowed in the sagittal plane. The CAS technology used was the VectorVision knee software, version 1.6.93616, with the Kolibri system (Brain-LAB, Munich, Germany).

Table 1.

Demographic data and preoperative characteristics of the patients

| CAS n = 24 |

CONV n = 24 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Men, n | 8 | 9 |

| Mean age, years | 67 | 66 |

| Charnley category, n | ||

| 1 | 8 | 7 |

| 2 | 14 | 16 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Diagnosis, n | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 17 | 19 |

| Other | 7 | 5 |

| Tibial component, n | ||

| Metaphyseal stem | 0 | 1 |

| Keeled | 24 | 23 |

Tranexamic acid (10 mg/kg) was administered intravenously 10 min before surgery and repeated 10 min before release of the tourniquet. No drains were used. The operated knee was positioned in 90° flexion for 2 h to minimize bleeding. Antithrombotic medication was administered 4 h postoperatively and once daily for 17 days (5000 IE dalteparin by subcutaneous injection). Antibiotic prophylaxis (cephalotin, 2 g) was administered intravenously 30 min before surgery, then after 4, 8, and 12 h. The skin incision was closed with staples. All patients started weight bearing and standardized exercises on the first postoperative day. Postoperative epidural catheter was used for pain control in the first 2 days.

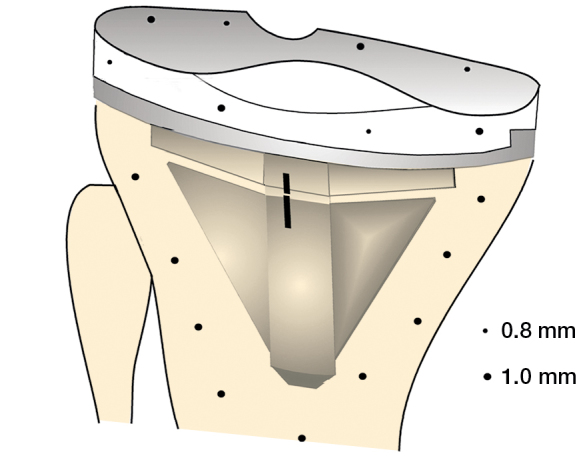

For the RSA analysis, 6 tantalum-sphere markers (diameter 0.8 and 1.0 mm) were inserted at operation into the plastic component of the tibia. 9 markers (1.0 mm in diameter) were spread out into the tibial metaphysis before the tibial base was cemented (Figure 1). As the CAS procedure requires extra incision in the mid-tibia, a sham incision was used in patients operated with the CONV technique

Figure 1.

Distribution of the 0.8-mm and 1.0-mm tantalum markers in the polyethylene component of the prosthesis.

Objectives and outcomes

The patients and observers (physiotherapists and radiologist) were blinded as to which surgical procedure was used. The follow-up period was 24 months, with scheduled follow-up visits at 3, 12, and 24 months.

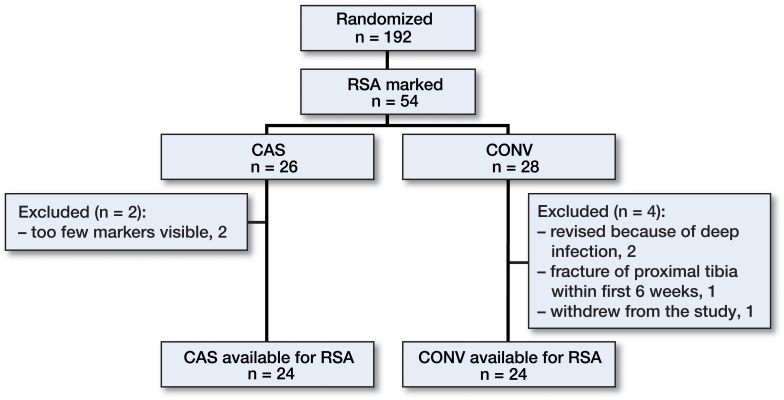

192 patients were included in the main study. Of those, 54 were enrolled in the present RSA study. 6 patients were excluded: 1 withdrew from the study, 3 were revised (all CONV), 1 because of fracture of the proximal tibia and 2 because of deep infection. 2 could not be analyzed further with RSA (both CAS) because of an insufficient number of visible markers on the radiographs (Figure 2). In all, 48 patients were available for final RSA analysis at 2 years (Table 1). 3 patients did not show up at the 3-month RSA follow-up and 4 patients did not show up at the 1-year RSA follow-up. Due to inferior quality of stereo radiographs, 4 patients could not be analyzed at 3 months postoperatively.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of the patients.

Clinical outcome was evaluated with Knee Society score (KSS), knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS), EQ-5D, and a visual analog scale (VAS) for pain. Clinical outcome at 1 year has been published together with radiographic findings for the main study (Gøthesen et al. 2014).

The index RSA examination was done on day 6 or 7 and RSA examinations were repeated at 3, 12, and 24 months after surgery. The patient was supine with the knee positioned inside a biplane calibration cage (cage 10; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) according to the technique described earlier (Henricson et al. 2008). 1 gantry-mounted X-ray tube and 1 portable X-ray tube were used to obtain 2 simultaneous exposures at a 90° angle. For radiographic imaging, we used high-definition digital plates (Agfa CR MD 4.0) and for plate reading we used the ADC compact digitizer (Agfa).

The investigator involved in the RSA measurements (KH) was blind regarding patient allocation. Sometimes, however, the holes in the tibia and femur made by the fixator pins used to secure the navigation towers were revealed on the images being measured. RSA measurements were possible if 3 or more markers could be identified in each segment from repeated examinations.

Translation and rotation of the tibial component relative to tibial bone was calculated using the markers in the tibia as the fixed reference segment and the markers in the polyethylene insert as the moving segment (UmRSA Digital Measure version 6.0; RSA Biomedical). The movements of the implant were measured along and around a medially directed axis (x-axis, anteroposterior rotation (AP)), longitudinal axis (y-axis, internal-external rotation), and sagittal axis (z-axis, varus-valgus rotation) of the knee. To ensure proper stability and distribution of the tantalum markers, the upper limit for the mean error of rigid-body fitting was set at 0.25 and the upper limit for the condition number was set at 100 (Valstar et al. 2005, Henricson et al. 2008). To ensure identical points of measurement of the translation, standardized positions on the tibial tray were defined as described previously (Nilsson et al. 1991). Translations were expressed as the maximum total point motion (MTPM), subsidence, and lift-off. MTPM represents the 3-D vector of the prosthetic marker that moved the most and corresponds to the magnitude of the migration only (Ryd et al. 1995). For each implant, the largest negative value for y-translation was called maximum subsidence and the largest positive y-translation was called lift-off. The calculations were performed according to the orthogonal right-hand coordinate system.

Statistics

The numbers included in the study were determined by power analyses, claiming 0.1 mm as a clinically relevant between-group difference, with a repeatability of 0.1 mm in the RSA measurements. A group sample size of 17 would achieve 80% power to detect a difference of 0.1 between groups with an estimated standard deviation of 0.1 and with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05, using a 2-sided, 2-sample t-test. To ensure proper sample sizes at 2 and 5 years, we chose to include 54 patients, with 28 in each group.

To evaluate the precision of the RSA measurements, the difference between double measurements was computed after 1 year. Secondly, we calculated the standard deviation (SD) of the differences with respect to zero (Ranstam et al. 2000).

Only absolute values were analyzed, since the main interest of the study was the amount and progression of migration, where both negative and positive values were possible (the sign indicates the direction of movement).

We compared the CAS and CONV groups regarding migration by using the Mann-Whitney test. The migration data were tested with the Shapiro-Wilk and Pearson tests for normality and were not normally distributed. Thus, both the median and interquartile range (IQR) are given. For statistical analysis, the median difference and the corresponding CI for the median difference for each migration and clinical parameter were calculated as described by Campbell and Gardner (1988). Differences in age, sex, Charnley category, and diagnosis were assessed by Pearson’s chi-squared test. Any p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Statistical evaluation was performed using SPSS software version 21.0 and the R package.

Ethics and registration

The study was registered in the trial database at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT00782444) on October 30, 2008. The trial was approved by the regional committee for medical and health research ethics, Bergen, Norway, on September 29, 2007 (ref. no. 2007/12587-ARS).

Results

Implant migration

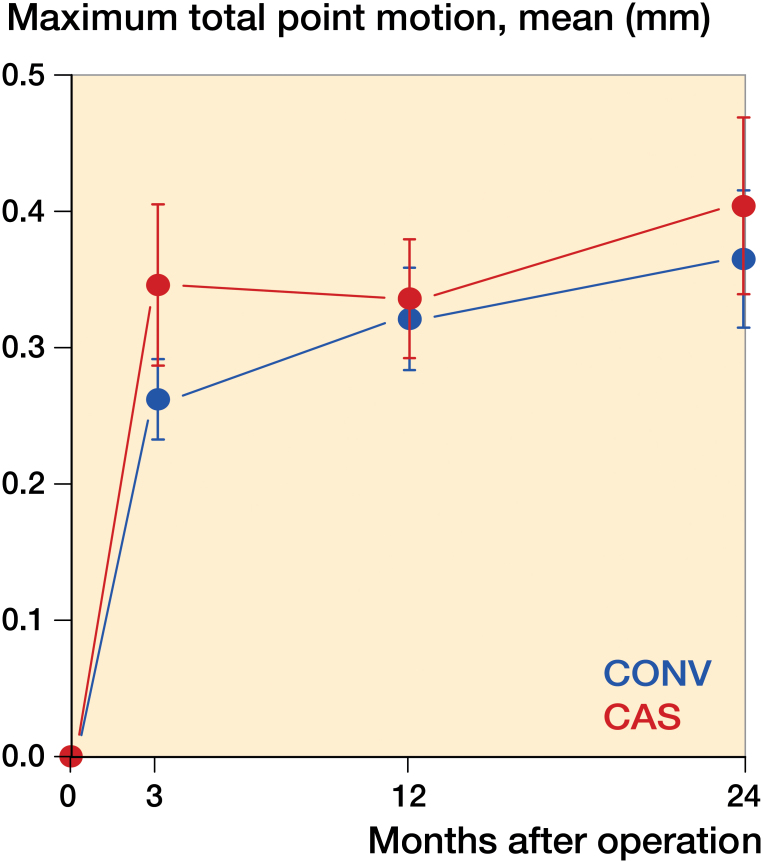

The tibial components in both groups migrated most during the first 3 months after surgery (Tables 2 and 3) and then appeared to stabilize. The difference in MTPM during the first 3 months, and between 3 months and 2 years was not statistically significantly different between the study groups (p = 0.8 and p = 0.1, Mann-Whitney test) (Figure 3).

Table 2.

Median differences in migration between CAS and CONV cemented tibial components, up to 2 years

| Median difference |

(95% CI) |

p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS vs. CONV at 12 months | |||

| x rotation | 0.01 | (−0.07 to 0.12) | 0.7 |

| y rotation | 0.03 | (−0.05 to 0.13) | 0.4 |

| z rotation | −0.02 | (−0.06 to 0.03) | 0.4 |

| MTPM | −0.02 | (−0.09 to 0.15) | 0.6 |

| Maximum lift-off | 0.01 | (−0.06 to 0.09) | 0.9 |

| Maximum subsidence | −0.01 | (−0.07 to 0.03) | 0.6 |

| CAS vs. CONV at 24 months | |||

| x rotation | 0.02 | (−0.06 to 0.10) | 0.6 |

| y rotation | 0.02 | (−0.03 to 0.10) | 0.4 |

| z rotation | 0.02 | (−0.07 to 0.10) | 0.7 |

| MTPM | −0.02 | (−0.11 to 0.09) | 0.6 |

| Maximum lift-off | −0.02 | (−0.09 to 0.06) | 0.8 |

| Maximum subsidence | 0.01 | (−0.05 to 0.06) | 0.6 |

Table 3.

Migration up to 2 years

| CAS |

CONV |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median |

IQR |

Mean |

95% CI |

Median |

IQR |

Mean |

95% CI |

|

| x-axis rotation [flexion-extension] (degrees, absolute value) | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.11 | 0.02–0.29 | 0.19 | 0.09–0.29 | 0.11 | 0.04–0.19 | 0.12 | 0.08–0.16 |

| 12 months | 0.15 | 0.08–0.24 | 0.18 | 0.12–0.23 | 0.13 | 0.04–0.22 | 0.19 | 0.09–0.28 |

| 24 months | 0.17 | 0.07–0.26 | 0.21 | 0.11–0.31 | 0.11 | 0.06–0.24 | 0.22 | 0.07–0.38 |

| y-axis rotation [internal-external] (degrees, absolute value) | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.14 | 0.07–0.29 | 0.20 | 0.11–0.29 | 0.13 | 0.04–0.24 | 0.13 | 0.08–0.18 |

| 12 months | 0.13 | 0.05–0.26 | 0.15 | 0.10–0.21 | 0.10 | 0.03–0.32 | 0.16 | 0.08–0.23 |

| 24 months | 0.16 | 0.07–0.21 | 0.21 | 0.10–0.32 | 0.12 | 0.05–0.19 | 0.12 | 0.09–0.15 |

| z-axis rotation [varus-valgus] (degrees, absolute value) | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.09 | 0.05–0.15 | 0.12 | 0.07–0.17 | 0.12 | 0.07–0.13 | 0.14 | 0.09–0.19 |

| 12 months | 0.09 | 0.05–0.30 | 0.17 | 0.09–0.25 | 0.10 | 0.05–0.17 | 0.13 | 0.08–0.19 |

| 24 months | 0.13 | 0.04–0.31 | 0.18 | 0.10–0.27 | 0.11 | 0.05–0.22 | 0.14 | 0.09–0.19 |

| MTPM (maximum total point motion, mm) | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.22 | 0.16–0.53 | 0.33 | 0.22–0.45 | 0.24 | 0.20–0.31 | 0.27 | 0.21–0.33 |

| 12 months | 0.30 | 0.19–0.44 | 0.34 | 0.25–0.42 | 0.28 | 0.22–0.37 | 0.31 | 0.25–0.39 |

| 24 months | 0.27 | 0.21–0.51 | 0.40 | 0.27–0.52 | 0.32 | 0.25–0.41 | 0.37 | 0.27–0.47 |

| Maximum lift-off, mm | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.11 | 0.04–0.25 | 0.14 | 0.09–0.19 | 0.10 | 0.03–0.16 | 0.14 | 0.07–0.20 |

| 12 months | 0.10 | 0.07–0.21 | 0.15 | 0.09–0.22 | 0.11 | 0.05–0.24 | 0.18 | 0.10–0.26 |

| 24 months | 0.10 | 0.06–0.28 | 0.18 | 0.10–0.25 | 0.16 | 0.06–0.21 | 0.19 | 0.10–0.29 |

| Maximum subsidence, mm | ||||||||

| 3 months | 0.08 | 0.04–0.15 | 0.10 | 0.06–0.15 | 0.08 | 0.00–0.11 | 0.07 | 0.05–0.11 |

| 12 months | 0.08 | 0.01–0.18 | 0.09 | 0.04–0.14 | 0.06 | 0.00–0.08 | 0.06 | 0.03–0.09 |

| 24 months | 0.05 | 0.00–0.15 | 0.10 | 0.04–0.16 | 0.07 | 0.04–0.14 | 0.09 | 0.06–0.13 |

IQR: interquartile range.

Figure 3.

Maximum total point motion.

No tibial components migrated more than 0.1 mm between 12 and 24 months. The component that migrated most had an MTPM of 0.09 mm during the second year of observation. There were no outliers.

The total rotational migration (in degrees) was similar between groups at all 4 follow-up times (Tables 2 and 3). There was no trend of any 1-directional migration pattern; we found an even distribution between positive and negative migration values in both groups.

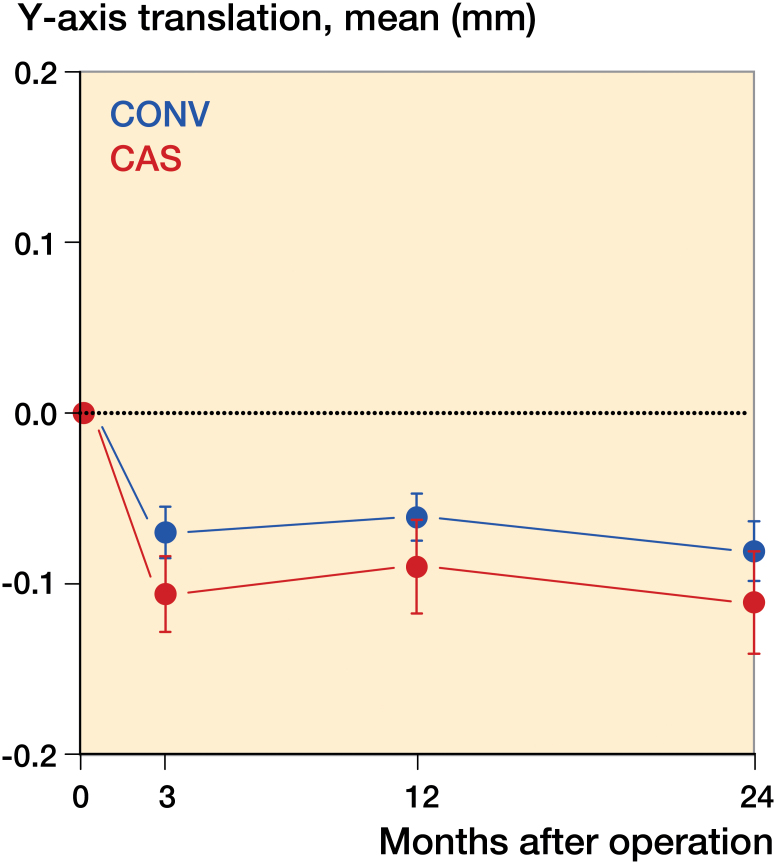

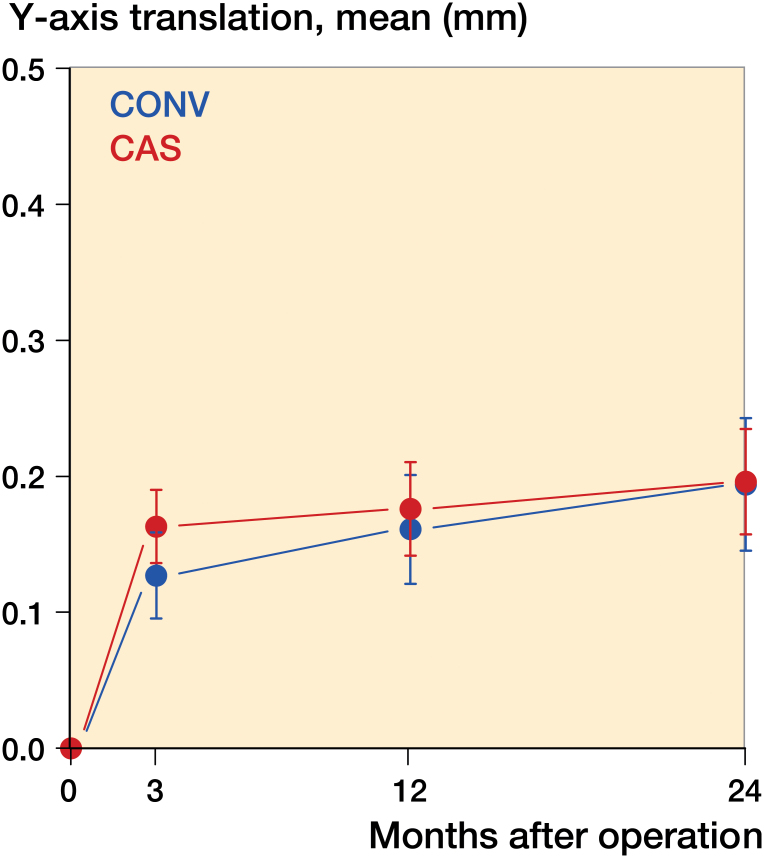

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups for maximal subsidence and lift-off between 3 months and 2 years (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Subsidence, i.e. largest negative value for y-axis translation.

Figure 5.

Lift-off, i.e. largest positive value for y-axis translation.

The mean error of rigid-body fitting was 0.12 (95% CI: 0.11–0.13) and the condition number was 30 (95% CI: 34–40).

Radiographic findings

The main aim was to achieve a neutral alignment on long-axis radiographs. 10 patients ended up with a mechanical axis that deviated more than 3° into varus or valgus from this axis. 4 of these were CAS-operated TKAs and 6 were CONV-operated TKAs. These 10 patients were classified as outliers. When comparing outliers to neutrally aligned knees, we found no significant difference in MTPM between 3 months and 2 years (p = 1.0).

Discussion

We measured the degree of migration for TKA operated using CAS or CONV technique and we found no statistically significant differences in mean MTPM, subsidence, lift-off, or rotational movements between the 2 groups. Earlier studies have indicated that early migration correlates with later loosening of TKA. Our results indicate that the risk of loosening should be similar in both groups. Neither of these techniques is superior. According to Valstar et al. (2012), there is growing awareness that new joint replacement prostheses, cement, and surgical techniques should be thoroughly evaluated before general release onto the market and that RSA studies should play an important role in this evaluation.

Strengths and limitations

To date, no RCTs have directly compared CAS and CONV technique using radiostereometry. The main strength of our study is that it was an RCT designed to directly compare migration of CAS- and CONV-operated TKAs. The number of patients was sufficient for us to evaluate whether there was a statistically significant difference in implant migration between the 2 groups (Kärrholm et al. 1994, Ryd et al. 1995, Valstar et al. 2005). The trial was designed to study migration in TKAs in patients aged 50–85 years. The main limitation is that the number of patients was too low for us to evaluate subgroups (age groups, implant sizes, and alignment) within the study population.

Current knowledge

Ryd et al. (1995) used RSA as a predictor of mechanical knee implant loosening. Migration of more than 2 mm between 1 and 2 years was considered to be “continuous migration”, with an increased risk of aseptic loosening. Pijls et al. (2012) confirmed that migration measurements from RSA tests can predict subsequent loosening of knee prostheses.

A recent Cochrane review concluded that cemented implants migrate less than uncemented ones, with lower displacement in cemented implants when evaluating MTPM at 2 years (Nakama et al. 2012). However, cemented implants showed a higher risk of aseptic loosening due to a continuous migration pattern. The uncemented components stabilized after an initial period of early and greater migration, whereas the cemented components showed no tendency to stabilize over time. 1 publication found a cemented tibial component to be stable without continuous migration after 5 years (Henricson et al. 2013), and another after 2 years (Tjørnild et al. 2014). In the present study, all the implants were cemented. No implant migrated more than 0.2 mm between 1 and 2 years. All implants showed early migration and stabilization, with similar migration patterns.

In a registry-based study, de Steiger et al. (2015) found that computer navigation reduced the overall rate of revision and the rate of revision for loosening/lysis following TKA in patients less than 65 years of age. We found higher MTPM in patients younger than 65 who were operated with CAS rather than CONV, but this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.2), probably due to low power.

In a study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty registry (NAR), the main conclusion was that the short-term risk of revision was either the same or higher for CAS, and depended more on prosthesis brand (Gøthesen et al. 2011). The frequency of use of CAS in Norway peaked at 21% in 2008, but it was 8% in 2015 (NAR 2015).

Clinical relevance

This is the first RSA study to have directly compared CAS- and CONV-operated TKAs. RSA studies play an important role in the documentation of new techniques in joint replacement surgery, and some authors propose that this should be mandatory before larger clinical trials can be initiated.

Conclusion

We found similar migration of the tibial component in TKAs operated using computer-aided surgery and in TKAs operated using conventional technique.

GP, ØG, AA, KGN, and OF planned the study and analyzed the data. AMF and OF supervised the analyses. KH analyzed RSA images. All the authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

No competing interests declared. The study was financially supported by the Research Council of Norway and South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority.

We thank orthopedic surgeons H. Luhr, T. Jervidalo, A. Skredderstuen, and C. Jacobsen for participating in this trial by recruiting and operating patients, and we give a special thanks to all participating patients. We also acknowledge our radiographer for all the work that was done, spending many hours on RSA images.

References

- Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report. Adelaide: AOA; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens K, Matthes G, Wich M, Gebhard F, Hanson B, Ekkernkamp A, Stengel D.. Navigated total knee replacement. A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007; 89 (2):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellemans J. Neutral mechanical alignment: a requirement for successful TKA: opposes. Orthopedics 2011; 34: 507–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney W G, Khan R J K, Wall S J.. Computer-assistet technique versus conventional guides for component alignment in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011; 93: 1377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeney W G, Khan R J, Palmer J L.. Functional outcomes following total knee arthroplasty: a randomised trial comparing computer-assisted surgery with conventional techniques. Knee 2014;21(2): 364–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M J, Gardner M J.. Calculating confidence intervals for some non-parametric analyses. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988; 296(6634): 1454–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan S K, Scott R G, Breidahl W, Beaver RJ .. Computer-assisted knee arthroplasty versus a conventional jig-based technique. A randomised, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86-B: 372–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Shao S, Peng X, Shang X.. Does computer-assisted surgery improve postoperative leg alignment and implant positioning following total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20: 1307–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choong P F, Dowsey M M, Stoney J D.. Does Accurate anatomical alignment result in better function and quality of life? Comparing conventional and computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24: 560–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis DA, Komistek RD, Kim RH, Sharma A.. Gap balancing versus measured resection technique for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 102–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrhovden G S, Gøthesen Ø, Lygre S H L, Fenstad A M, Sørås T E, Halvorsen S, Jellestad T, Furnes O.. Is the use of computer navigation in total knee arthroplasty improving implant positioning and function? A comparative study of 198 knees operated at a Norwegian district hospital. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013; 14: 321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring T K, Odum S, Friffin W L, Mason J B, Nadaud M.. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; 392: 315–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gøthesen Ø, Espehaug B, Havelin L, Petursson G, Furnes O.. Short-term outcome of 1,465 computer-navigated primary total knee replacements 2005-2008. A report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(3): 293–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gøthesen Ø, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Petursson G, Hallan G, Strøm E, Dyrhovden GS, Furnes O.. Functional Outcome and alignment in computer assisted and conventionally operated total knee replacements. A multicenter parallel group randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B: 609–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricson A, Linder L, Nilsson K G.. A trabecular metal tibial component in total knee replacement in patients younger than 60 years. A two-year radiostereophotogrammetric analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90: 1585–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricson A, Rösmark D, Nilsson K G.. Trabecular metal tibia still stable at 5 years. An RSA study of 36 patients aged less than 60 years. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(4): 398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F.. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-years stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994; 76:912–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kärrholm J, Gill R H S, Valstar E R.. The History and Future of Radiosterometric Analysis. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2006: 448: 10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y H, Kim J S, Choi Y, Kwon O R.. Computer-assisted surgical navigation does not improve the alignment and orientation of the components in total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91(1): 14–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lad D G, Thilak J, Thadi M.. Component alignment and functional outcome following computer assisted and jig based total knee arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop 2013; 47(1): 77–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longstaff L M, Sloan K, Stamp N, Scaddan M, Beaver R.. Good alignment after total knee arthroplasty leads to faster rehabilitation and better function. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24(4): 570–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüring C, Bäthis H, Tingart M, Perlick L, Grifka J.. Computer assistance in total knee replacement – a critical assessment of current health care technology. Comput Aided Surg 2006; 11: 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lützner J, Dexel J, Kirschner S.. No difference between computer-assisted and conventional total knee arthroplasty: five-year results of a prospective randomised study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013; 21(10): 2231–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K G, Kärrholm J, Ekelund L, Magnusson P.. Evaluation of micromotion in cemented vs uncemented knee arthroplasty in osteoarthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Arthroplasty 1991; 6: 265–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Arthroplasty Register Norwegian National Advisory Unit on Arthroplasty and Hip Fractures. Helse Bergen HF, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Haukeland University Hospital 2015: http://nrlweb.ihelse.net. [Google Scholar]

- Parratte S, Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T, Berry D J.. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92-A: 2143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pijls B G, Valstar E R, Nouta K A, Plevier J W M, Fiocco M, Middeldorp S, Nelisson R G G H.. Early migration of tibial components is associated with late revision. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 21,000 knee arthroplasties. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(6): 614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter M A, Faris P M, Keating E M, Meding J B.. Postoperative alignment of total knee replacement. Its effect on survival. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994; 299: 153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryd L, Albrektsson B E J, Carlsson L, Dansgård F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, Regnèr L, Toksvig-Larsen S.. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995; 77-B: 377–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz K F, Altman D G, Moher D, CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010; 340: 332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Wei Y, Wang S, Chen F, Wu J, Huang G, Chen J, Wei L, Xia J.. Computer navigation and total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2014; 37(1): e39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J M, Chauhan S K, Sloan K, Taylor A, Beaver R J.. Computer navigation versus conventional total knee replacement: no difference in functional results at two years. J Bone Joint Surg Br: 2007; 89(4): 477–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Steiger R N, Liu Y L, Graves S E.. Computer navigation for total knee arthroplasty reduces revision rate for patients less than Sixty-five years of age. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2015; 97: 635–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjørnild M, Søballe K, Hansen P M, Holm C, Stilling M.. Mobile- vs. fixed-bearing total knee replacement. A randomized radiostereometric and bone mineral density study. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(2): 208–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valstar E R, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J.. Guidelines for standardization of radiosterometry (RSAI of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76: 563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valstar E R, Kaptein B, Nelissen R. Guest editorial . Radiosterometry and new prostheses. Acta Orthop 2012; 83(2): 103–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien T, van der Linden-van der Zwaag E, Kaptein B, van Erkel A, Valstar E, Nelissen R.. Computer assisted versus conventional cemented total knee prostheses alignment accuracy and micromotion of the tibial component. Int Orthop 2009; 33(5): 1255–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside L A. Soft tissue balancing the knee. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17 (4 Suppl1): 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside L A, Arima J.. The anteroposterior axis for femoral rotational alignment in valgus total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995; 321: 168–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]