Abstract

Background

Age is suggested as a triage criteria for transfer to a trauma center, despite poor outcomes after similar injury regardless of trauma center level. The effect of differential triage based on age to a trauma center has not been evaluated. We hypothesized that there would be a difference in the admission rates of geriatric patients compared to the rest of the adult trauma population independent of injury severity.

Methods

Records of 1970 adult patients evaluated by the trauma team at a Level 1 trauma center and discharged directly from the ED were reviewed. Data abstracted included demographics, injuries, and physiologic information. These data were compared to 3232 trauma patients admitted over the same time period who had similar information abstracted via record review. Chi-squared analysis of the admission rates of geriatric patients was performed, followed by a binomial logistic regression to determine factors that affected the odds of admission.

Results

8.68% (451) of the patients were age 65 or older. 62.2% of the total population was admitted. Significantly more geriatric patients (82%) were admitted (χ2=126.24, p<0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that age, head injury, ISS, GCS, and initial blood pressure were significant independent factors in predicting hospital admission (p <0.001).

Conclusions

Age alone is associated with increased odds of being admitted to the hospital, independent of injury severity and other physiologic parameters. This has implications for trauma centers that see a significant proportion of geriatric trauma patients, as well as for trauma systems that must prepare for the “aging of America”.

Keywords: Geriatric Trauma, Trauma admission criteria

Introduction

As America ages, and the proportion of the elderly population increases, the overall utilization of health resources will also continue to rise. This will affect trauma centers, an area of health care system that has typically been considered a disease primarily of the young. Based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, over 21.9 million people suffered traumatic injury in 2008, of which approximately 3.3 million (roughly 15%) were age 65 or older1. Between the increasing proportion of elderly in the population and advances in health care improving quality and quantity of life, the proportion of elderly patients suffering traumatic injury will only continue to increase.

Many studies have investigated how advanced age may influence patient outcomes and ultimately what role age should play in the management of trauma patients. These have covered a broad range of topics and not surprisingly controversy still remains. For example, the role age plays in early pre-hospital triage decisions is important in determining where a patient is sent following trauma2–3. Some studies promote age of >704, or even >555, as an activation criteria for transfer to a trauma center, while others indicated inclusion of age a criterion causes “inappropriate” activations6 and that it should be considered a lower tier criteria at best. There is evidence to support early intervention in geriatric patients2,3, and contradictory evidence suggesting intervention is futile due to low probability of recovery in even moderate chest and abdominal injuries7. Comorbidities, much more prevalent in the older population, may affect the mortality of these patients following trauma, again with some supporting evidence8 and some opposing9.

Despite these differences, there are fairly consistent recommendations that special considerations should be given to geriatric trauma patients2,10. However, there has been little investigation into the impact that a cautious approach to geriatric trauma will have on health care resources. Obviously, improved patient outcomes should be of primary concern and in many cases caution and extended observation may be the best policy. However, with appropriate selection, discharge home directly from the emergency department following traumatic injury in the elderly can result in good outcomes11. The goal of this study was to examine the geriatric admission practices of a single Level 1 Trauma Center, with the specific aim of determining whether age independently increased the likelihood of admission. In addition, the specific reasons for admission of geriatric patients were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A database of directly discharged trauma patients was developed retrospectively through systematic chart reviews of 1970 patients seen at Froedtert Memorial Lutheran Hospital (FMLH), a Level 1 Trauma Center. The electronic records of all patients seen as either trauma alerts or calls, indicating full or partial trauma team activation, who were discharged directly from the Emergency Department (ED) between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2006, were reviewed. Over 50 data points were recorded for each patient including demographic information, initial hospital vital signs, injuries, pre-existing comorbidities, and aspects of their initial trauma evaluation such as presence of a staff trauma surgeon and radiologic studies performed. Based on the documented injuries, abbreviated injury scale scores (AIS) and injury severity scores (ISS) were assigned to each patient. Moderate injury was defined as an ISS >15 and severe as an ISS >2512. This information was then used in conjunction with 3232 patients from the institution’s trauma registry, which records data on all admitted trauma patients, over the same time period.

To evaluate whether or not there was a statistically significant difference between the admission rates of elderly patients compared to the rest of the adult trauma population, chi-squared analysis was performed. Our cut off age for “elderly” patients was defined as age 65 or older based on current US Medicare standards. Multivariate logistic regression was then used on a subset of 4390 patients, which included those patients in whom all relevant data points including patient age, admission status, presence of head injury, arrival GCS13, ISS, and systolic BP were available. These were considered to be our clinically significant factors that needed to be corrected for in order to determine which would be correlated with increased or decreased odds of admission. Length of stay and days in the surgical intensive care unit were analyzed for all admitted patients as markers of whether or not the admission was for continued high level of care or short term observation.

RESULTS

Demographics

5202 injured patients were evaluated by the trauma service at FMLH during the 2 year study period. Of the 1970 discharged patients, 2 patients were excluded as they were either admitted or transferred to a different institution and 2 were excluded as there was no verified documentation of their age. Of the 3232 admitted patients, 1 was excluded as there was no verified age documented. Overall, 451 patients, or 8.68% of the population, were age 65 or over. Further age break down and trauma mechanisms for the overall population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overall Demographics

| Number of Patients | Percent of Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5197 | 100.0 | |

| Mechanism | Blunt | 4000 | 77.0 |

| Penetrating | 1197 | 23.0 | |

| Age (yrs) | ≤24 | 1332 | 25.6 |

| 25–34 | 1179 | 22.7 | |

| 35–44 | 1029 | 19.8 | |

| 45–54 | 815 | 15.7 | |

| 55–64 | 391 | 7.5 | |

| ≥65 | 451 | 8.7 |

Of the remaining 1966 discharged patients, 1876 originally presented to FMLH as trauma calls and 90 as trauma alerts. The majority of patients, 1335, were male and most, 1525, suffered blunt trauma. The ages of discharged patients ranged from 17 to 88, with an average of 34.34 yrs and median of 31.5 yrs. Elderly patients made up 3.05% of the total discharged population (Table 2).

Table 2.

Discharged Demographics

| Number of Patients | Percent of Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1966 | 100.0 | |

| Trauma Status | |||

| Alerts | 90 | 4.6 | |

| Calls | 1876 | 95.4 | |

| Sex | Male | 1335 | 67.9 |

| Female | 631 | 32.1 | |

| Mechanism | Blunt | 1525 | 77.6 |

| Penetrating | 441 | 22.4 | |

| Age (yrs) | ≤24 | 601 | 30.6 |

| 25–34 | 511 | 26.0 | |

| 35–44 | 416 | 21.2 | |

| 45–54 | 262 | 13.3 | |

| 55–64 | 116 | 5.9 | |

| ≥65 | 60 | 3.1 | |

| Mean | 34.34 yrs | — | |

| Median | 31.5 yrs | — |

Of the 3231 admitted patients, the majority, 2475, suffered blunt trauma. The age of admitted patients ranged from 13 to 99, with an average of 40.8 yrs and median of 38.2 yrs. Elderly patients made up 12.1% of the admitted population (Table 3).

Table 3.

Admitted Demographics

| Number of Patients | Percent of Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 3231 | 100.0 | |

| Mechanism | Blunt | 2475 | 76.6 |

| Penetrating | 756 | 23.4 | |

| Age (yrs) | ≤24 | 731 | 22.6 |

| 25–34 | 668 | 20.7 | |

| 35–44 | 613 | 19.0 | |

| 45–54 | 553 | 17.1 | |

| 55–64 | 275 | 8.5 | |

| ≥65 | 391 | 12.1 | |

| Mean | 40.8 yrs | — | |

| Median | 38.2 yrs | — |

Admission

Over the two year period, approximately 62.2%, of the overall trauma population were admitted for further care. That number was significantly higher for patients age 65 or older (86.7%;χ2 = 126.64, p <0.001). Binomial regression indentified several independent factors that had significant correlation (p<0.001) predicting hospital admission including age greater than 64 (OR 3.76), presence of head injury (OR 5.3), moderate (≥15) ISS (OR 17.5), GCS on arrival to hospital (OR 0.753), and initial hospital systolic blood pressure (OR 0.987) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors Correlated with Hospital Admission

| Discharged | Admitted | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older than 64 (%) | 3.05 | 12.1 | 3.761 | 2.646 – 5.350 |

| Head Injury (%) | 1.58 | 28.07 | 5.302 | 3.490 – 8.053 |

| ISS moderate (%) | 0.86 | 24.69 | 17.526 | 10.570 – 29.079 |

| GCS on arrival | 14.87 | 12.55 | 0.749 | 0.702 – 0.801 |

| ED systolic BP | 135.2 | 124.87 | 0.988 | 0.984 – 0.992 |

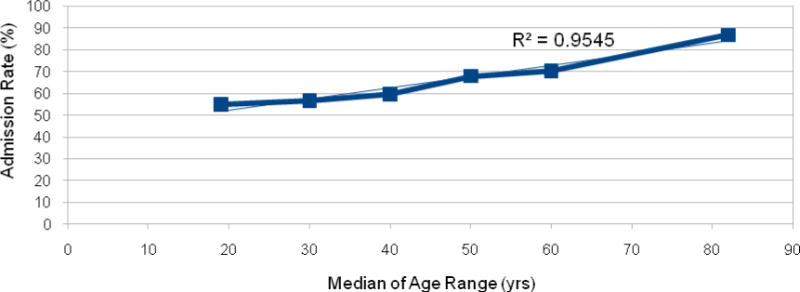

Examination of specific age groups, treating age as a continuous variable, also showed a trend correlating with increasing admission rate as age increased (R2 = 0.95), (Table 5; Figure 1).

Table 5.

Admission Rates for Defined Age Groups

| Age Range (yrs) | Median of Age Range (yrs) | Discharged Patients | Admitted Patients | Total Patients | Admission Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤24 | 19 | 601 | 731 | 1332 | 54.9 |

| 25–34 | 30 | 511 | 668 | 1179 | 56.7 |

| 35–44 | 40 | 416 | 613 | 1029 | 59.6 |

| 45–54 | 50 | 262 | 553 | 815 | 67.9 |

| 55–64 | 60 | 116 | 275 | 391 | 70.3 |

| ≥65 | 82 | 60 | 391 | 451 | 86.7 |

Figure 1.

Admission Rate vs. Median of Age Range

Hospital Stay

For the admitted population, the average ISS was 12.92 (SD 9.74), Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission rate was 41.2% and length of hospital stay (LOS) was 6.85 days (SD 9.27). Elderly patients had a higher ISS (14.87 vs. 12.66) and longer LOS (8.03 days vs. 6.69 days) than those < 65. Elderly patients were also admitted to the SICU at a higher rate (60.9 vs. 38.5, χ2 = 69.92, p<0.001) and were more likely to remain there for a longer period of time (Table 6).

Table 6.

Aspects of Hospitalization

| <65 yrs | ≥65 yrs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Average ISS (+/−st. deviation) |

12.66 (+/−9.74) |

14.84 (+/−5.18) |

|

|

SICU Admission (%) |

38.5 | 60.9 | |

| 1 ICU day (%) | 50.3 | 42.9 | |

| ≤2 ICU days (%) | 63.7 | 57.6 | |

| ≥3 ICU days (%) | 36.0 | 42.4 | |

|

Length of Stay (days, average +/− st. deviation) |

6.69 (+/−9.42) |

8.03 (+/−8.08) |

|

| 1 day (%) | 22.3 | 16.1 | |

| ≤2 days (%) | 36.7 | 22.5 | |

| ≥3 days (%) | 63.0 | 77.5 | |

DISCUSSION

America is aging, and as we do diseases historically associated with the young–such as trauma–will play a major role in the health care needs of our “new” old. The recommendation that age function as a criterion for triage to a trauma center has significant consequences for trauma centers and system resources. Once transferred, we found that patients age 65 or greater are nearly 4 times more likely to be admitted than younger patients with similar injuries. Additionally, the admission trends we discovered seem to indicate that age may be more of a continuous variable than just a specific cut off at age 65. This effect was found to be independent of several other factors including presence of a head injury, GCS at initial trauma evaluation, ISS, and other physiologic parameters. This is especially important as this trend exists despite the fact that trauma centers do not provide the same outcome benefit for the elderly as they do for younger patients14. Our data also demonstrate that geriatric patients are admitted to the ICU at a greater frequency. Over 60% of geriatric trauma patients were admitted to the ICU compared to 38.5% of the rest of the adult population. This may be the result of specific practice patterns related to geriatric patients. For instance, rib fractures are known to increase mortality in geriatric populations compared with younger patients, so our practice is to admit geriatric patients with rib fractures to the ICU independent of their physiologic status15. However, over 40% of patients in both age cohorts were transferred to the floor after 1 day which supports the idea that intense observation for rapid deterioration is the initial reason for many ICU admissions.

It has been previously established that age, in addition to multiple other non clinical factors, is an independent predictor of increased length of hospital stay16. Therefore, a higher percentage of short stays among elderly patients would support the hypothesis that many are admitted for observation rather than for care. This pattern was not observed in our population. In fact, elderly patients not only had longer hospital stays on average, but fewer were discharged on hospital day 1 or 2, with over 75% remaining 3 days or more. This may be explained by factors including social issues related to care after discharge, such as family support or lack thereof, deconditioning, as well as the time spent in the ICU.

If geriatric patients are more likely to be admitted to the ICU and for a longer period of time, the additional ICU days would skew their overall LOS. It is highly unlikely a geriatric patient would be discharged directly home from the ICU, rather transitioning to the general floor first. This would increase the LOS compared to a patient initially admitted to the general surgical floor. It should be pointed out that ICU days related to mechanical ventilation would also affect these trends, and carry with it their own morbidity, but were not part of the focus of this analysis. Another concern surrounding the practice of hospitalizing elderly patients is the risk of deconditioning unrelated to their original injury17. The time in the SICU and hospital itself may lead to additional hospital days for physical or occupational therapy and management of chronic conditions due to the hospital-associated deconditioning.

There are many limitations to this study. First, as a retrospective study, we are left to infer from available records what the original providers’ thought processes were during evaluation of patients when they presented. It is felt that geriatric patients are more likely to be admitted partly due to less physiologic reserve than younger patients, and the concern that they may have delayed signs and symptoms of traumatic injury2. This seems to be part of the reasoning behind admission for “observation” in geriatric patients who appear to only have minor injuries. Determining if this was the reason for admission is inherently challenging, raises possibility for incorrect inferences, and further supports the fact that more research, especially prospective when possible, is needed in the area of geriatric trauma. Though the study size was fairly large, it is single institution data and therefore represents the practices of a single trauma center. In addition, we were unable to account for specific comorbities because of the lack of data in our admitted patients. However, prior investigation into this topic has found that age is a predictor of worsened outcomes independent of comorbidities8. Finally, our study population includes all trauma patients, including those suffering from blunt and penetrating mechanisms of injury. Despite the fact that penetrating injury, typically due to gunshot wounds or stabbing, tend to occur more frequently in a younger population, patients with both mechanisms were used for our final analysis. When analysis of blunt trauma patients only was performed, we found no difference when compared to the population that included penetrating injuries. For that reason we decided to analyze the entire population in order to maintain the power given by the larger size of our study population. In spite of this, trauma in the elderly will likely continue to be a result of primarily blunt mechanisms and therefore the most beneficial focus for future investigations.

It was never the intent of this investigation to advocate how to treat geriatric patients, rather to provide information on geriatric trauma admission rates. Increased rates of overall and ICU geriatric admissions will likely have larger implications on trauma centers as this age demographic increases in proportion. We have established that age alone is an independent predictor of admission after traumatic injury. It is not clear whether these admissions were for observation or intervention in this retrospective study. Ultimately, in order to make sure we are providing the best possible care, further investigation is needed ensure we are admitting these patients because they need to be, and not solely based on their age. This should eventually help us to properly select patients that are safe to go home after minor trauma to save them the morbidity of hospitalization and the cost to the hospital while appropriately treating those who do require higher levels of inpatient care.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Disclosure: Research reported in this publication was supported in part by a training grant from the National Institute On Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T35AG029793. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This paper was podium presentation at the 69th AAST conference in Boston.

There is nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Jacob Peschman, Medical College of Wisconsin.

Todd Neideen, Medical College of Wisconsin.

Karen Brasel, Medical College of Wisconsin.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2008. Available at: http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/nfirates2001.html html. Accessed October 14, 2009.

- 2.Jacobs D, Plaiser B, Barie P, et al. Practice Management Guidelines for Geriatric Trauma: The EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. J Trauma. 2003;54:391–416. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000042015.54022.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehmann R, Beekley A, Casey L, et al. The impact of advanced age on trauma triage decisions and outcomes: A statewide analysis. Am J Surg. 2009;197:571–575. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Old Age as a Criterion for Trauma Team Activation. Demetriades D, et al. J Trauma. 2001;51:754–757. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips S, Rond P, Kelly S, Swartz P. The Failure of Triage Criteria to Identify Geriatric Patients with Trauma: Results from the Florida Trauma Triage Study J Trauma: Injury. Infection, and Critical Care Issue. 1996;40(2):278–283. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199602000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trauma Team Activation Criteria as Predictors of Patient Disposition from the Emergency Department. Kohn M, et al. Acad Emerg Med Clinical Investigations. 2004;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb01364.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nirula R, Gentilello L. Futility of Resuscitation Criteria for the “Young” Old and “Old” Old Trauma Patient: A National Trauma Bank Analysis. J Trauma. 2004;57:37–41. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000128236.45043.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mortality in elderly injured patients: the role of comorbidities. Camilloni L, et al. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion. 2008;15(1):25–31. doi: 10.1080/17457300701800118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hollis S, Lecky F, Yates D, et al. The effect of pre-existing medical conditions and age on mortality after injury. J Trauma. 2006;61:1255–1260. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000243889.07090.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs D. Special considerations in geriatric injury. Cur Opin Crit Care. 2003;9:535–539. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200312000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrera P, Bartfield J, D’Andrea C. Geriatric Trauma: Outcomes of Elderly Patients Discharged From the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:629–632. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon W, Long WB. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;14:187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore L, Lavoie A, Camden S, et al. Statistical Validation of the Glasgow Coma Score. J Trauma. 2006;60:1238–1244. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195593.60245.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie W, et al. The National Study on Costs and Outcomes of Trauma. J Trauma. 2007;63:S54–S67. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815acb09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergeron E, Lavoie A, Clas D, et al. Elderly Trauma Patients with Rib Fractures Are at Greater Risk of Death and Pneumonia. J Trauma. 2003;54:478–485. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000037095.83469.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasel K, Lim H, Nirula R, Weigelt J. Length of Stay: An Appropriate Quality Measure? Arch Surg. 2007;142:461–466. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kortebein P. Rehabilitation for hospital-associated deconditioning. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:66–77. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181838f70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]