Abstract

Five bacterial strains were isolated from the hemocoel of the greater wax moth larvae (Galleria mellonella) infected with the entomopathogenic nematodes: Heterorhabditis bacteriophora HP88, Heterorhabditis indicus RM1 and Heterorhabditis sp (S1), Steinernema abbasi and Steinernema sp. (S II). Strains were identified as Photorhabdus luminescens HRM1, P. luminescens HS1, P. luminescens HP88, Xenorhabdus indica and X. nematophila ATTC19061 using 16S rDNA sequence analysis. To reveal the genetic diversity among these strains, three molecular markers (RAPD, ISSR and SRAP) were employed. RAPD analysis showed 73.8 and 54.5 polymorphism percentages for the Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus strains, respectively. ISSR analysis resulted in 70.1 and 75.2 polymorphism percentages among the Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus strains, respectively. The SRAP analysis indicated that 75.6 and 61.2% genetic polymorphism was detected among Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus strains, respectively. The cluster analysis grouped the three Photorhabdus strains together in one cluster and the two Xenorhabdus strains together in another cluster indicating the phylogenetic relationships among them. The genotype-specific markers detected from the three molecular markers (RAPD, ISSR and SRAP) were sufficient to distinguish between the different bacterial strains tested and can be used in the future IBM program that could be built on the use of these strains.

Keywords: Photorhabdus, Xenorhabdus, 16S rDNA, Molecular markers, Genetic diversity

Introduction

Xenorhabdus spp. and Photorhabdus spp. are motile, Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. These bacteria are symbiotically associated with nematodes of the families, Steinernematidae and Heterorhabditidae, respectively (Forst et al. 1997; Sheets et al. 2011; Ferreira et al. 2014). These symbiotic complexes are highly pathogenic for a wide range of insects and are, therefore, used worldwide as biological agents in crop control (Ehlers 2003; Goodrich-Blair and Clarke 2007; Del Valle et al. 2013).

Many symbiotic bacterial species and isolates are still to be identified or described. Several identification techniques are now available that range from total protein, isozyme profiles to DNA/DNA hybridization and sequence analysis of the 16S rDNA region (Akhurst and Boemare 1990; Boemare and Akhurst 2007; Lee and Stock 2010).

The availability of molecular markers such as 16S rDNA (Christensen et al. 1998), RAPD (Williams et al. 1990; Welsh et al. 1991), ISSR (Zietkiewicz et al. 1994) facilitates the development of phylogenetic relationships, identification and characterization of bacterial species.

The sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) system was developed by Li and Quiros (2001) to target overlapping coding and non-coding regions of the genome. Depending on the amplification of Open-Reading Frames (ORFs) using the GC-rich exons and the promoter (Li and Quiros 2001), SRAP not only amplifies the interval between genes and their non-coding flanking regions, but also tightly links to actual genes, which would generate a fingerprint of the coding sequences and permit easy isolation of these bands for sequencing (Yu et al. 2008). SRAP is used in genetic map construction, genealogical classification, gene tagging and cloning, population structure, genetic diversity and genetic linkage map of plants (Li et al. 2007; Zheng et al. 2010; Jiang and Liu 2011; Lu et al. 2012; Alghamdi et al. 2012). Furthermore, it was used to study genetic diversity in parasites of human and animal health (Li et al. 2009; Song et al. 2011).

In the present work, five bacterial isolates (three Photorhabdus and two Xenorhabdus) were identified at the molecular level based on the 16S rDNA region. Furthermore, the genetic polymorphism among the five bacterial isolates was investigated at the molecular levels using RAPD, ISSR and SRAP analyses. The obtained data were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. The genotype-specific markers were also determined.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture

Five bacterial isolates were isolated from the hemocoel of the greater wax moth larvae (Galleria mellonella) infected with different entomopathogenic nematode strains (Steinernema abbasi, Steinernema sp. (S II), Heterorhabditis bacteriophora HP88, Heterorhabditis indicus RM1 and Heterorhabditis sp. (S1)). The bacterial isolates were plated on Nutrient Bromothymol Blue Agar (NBTA) medium (Akhurst 1980). On which Phase I is distinguished from Phase II by its adsorption of bromothymol blue to produce a red core colony overlaid by dark blue and surrounded by a clear zone after 3–4 days of incubation at 25 °C (Wang et al. 2008). The NBTA medium contained 20 g nutrient agar (Difco), 25 mg bromothymol blue (s.d. FiNE_CHEM ltd), and 40 mg tripheyltetrazolium (BDH, England) in 1 L distilled water. The Phase I colony was selectively transferred to 5 mL LB broth (Difco), and incubated at 25 °C for 48 h with gentle agitation (100 rpm).

16S rDNA analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the nucleic acid extraction kit (Solgent, Korea) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated symbiotic bacteria were identified by nucleotide sequence analysis of 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA). The universal primer set used was a forward 27F (5′-AGA GTT TGA TCC TGG CTC AG-3′) and a reverse 1492R (5′-GGT TAC CTT GTT ACG ACT T-3′) (Ibrahim et al. 1993). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with genomic DNA as a template in a total volume of 50 μl containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.2 pmol of each primer, and Taq DNA polymerase (Promega®). The amplification was carried out in a DNA thermocycler (MWG BIOTECH Primuse) programmed as follows: (94 °C/4 min) 1, (94 °C/1 min, 58 °C/1 min and 72 °C/1 min) 35, (72 °C/7 min) 1 (Jiang et al. 2006; Shrestha and Lee 2012). The PCR products were eluted from agarose gels using Promega®’s Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified DNA fragments from each sample were sent for DNA sequencing.

RAPD analysis

RAPD-PCR was carried out according to the procedure reported by Williams et al. (1990). Eleven primers were used in this study (Table 1). Amplification reaction was carried out in 25 μL volume containing 50 ng of genomic DNA template, 2.0 μM primer (Operon Technology, Inc., Almeda, CA, USA), and 2.0 μM each of dNTPs mix, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase. The amplification was carried out in a DNA thermocycler (MWG-BIOTECH Primuse) programmed as follows: (94 °C/4 min) 1, (94 °C/1 min, 35 °C/1 min, and 72 °C/1 min) 35, (72 °C/7 min) 1.

Table 1.

The nucleotide sequences of RAPD, ISSR and SRAP primers used

| RAPD primer sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| OPE-L04 | GACTGCACAC | OPE-B04 | GGACTGGAGT |

| OPE-M15 | GACCTACCAC | OPE-P09 | GTGGTCCGCA |

| OPE-P15 | GGAAGCCAAC | OPE-F12 | ACGGTACCAG |

| OPE-E06 | AAGACCCCTC | OPE-K02 | GTCTCCGCAA |

| OPE-D20 | ACCCGGTCAC | OPE-Q14 | GGACGCTTCA |

| OPE-B10 | CTGCTGGGAC | ||

| ISSR primer sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| UBC807 | (AG)8T | UBC818 | (CA)8G |

| UBC808 | (AG)8C | IS3 | TTT(TCC)5 |

| UBC809 | (AG)8G | IS4 | CAT(CA)7T |

| UBC810 | (GA)8T | IS5 | ACA(TG)7 |

| UBC811 | (GA)8C | IS10 | (TCC)5AC |

| UBC815 | (CT)8G | UBC827 | (TG)8A |

| SRAP primer sequences | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Forward primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Reverse primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

| Me1 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGATA | Em2 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGC |

| Me2 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAGC | Em3 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGAC |

| Me5 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGAAG | Em4 | GACTGCGTACGAATTTGA |

| Me6 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGTAG | Em5 | GACTGCGTACGAATTAAC |

| Me10 | TGAGTCCAAACCGGGAC | Em6 | GACTGCGTACGAATTGCA |

ISSR analysis

ISSR amplification was performed according to Kafkas et al. (2006) using 12 primers (Table 1). Amplification reaction was carried out in 30 μL volume containing 50 ng of genomic DNA template, 2.0 μM primers, 2.0 μM each of dNTPs mix, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase. The amplification was carried out in a DNA thermocycler (MWG-BIOTECH Primuse) programmed as follows: (94 °C/4 min) 1, (94 °C/1 min, 40–60 °C/1 min, 72 °C/1 min) 40, and (70 °C/5 min) 1.

SRAP analysis

Twenty-five SRAP combinations of five forward and five reverse primers were used (Table 1). The polymerase chain reaction was carried out according to Li and Quiros (2001) and the modification of Baloch et al. (2010). Amplification reaction was carried out in 30 μL volume containing 50 ng of genomic DNA template, 2.0 μM forward primer, 2.0 μM reverse primer, and 2.0 μM each of dNTPs mix, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 1× buffer and 2 units of Taq DNA polymerase. The amplification was carried out in a DNA thermocycler (MWG-BIOTECH Primuse) programmed as follows: (94 °C/4 min) 1, (94 °C/1 min′, 35 °C/1 min, 72 °C/1 min) 5, (94 °C/1 min, 50 °C/1 min, 72 °C/1 min) 35, and (70 °C/5 min) 1.

Data analysis

All the genotypes were scored for the presence and absence of the RAPD, ISSR and SRAP bands. And the data were entered into a binary matrix as discrete variables, 1 for presence and 0 for absence of the character and this data matrix was subjected to further analysis.

The Excel file containing the binary data was imported into NT Edit of NTSYS-pc 2.02J. The 0/1 matrix was used to calculate similarity as DICE coefficient using SIMQUAL subroutine in SIMILARITY routine. The resultant similarity matrix was employed to construct dendrogram using sequential agglomerative hierarchical nesting (SAHN) based on the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic means (UPGMA) to infer genetic relationships and phylogeny (Sneath and Sokal 1973).

Results and discussion

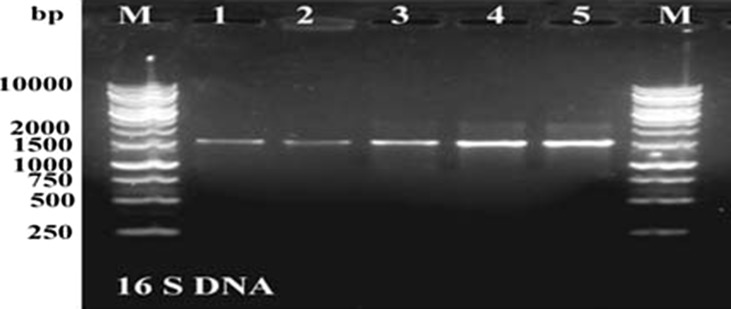

In the present study, three symbiotic bacterial strains isolated from Heterorhabditis family and two from Steinernema family were identified using 16S rDNA sequence analysis. The data indicated that 1530 bp fragment was amplified; these bands were eluted and sequenced (Fig. 1). The complete 16S rDNA gene sequences of all strains (1530 nucleotides) were aligned to the homologous sequences of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus using the BLASTN program in the NCBI (Altschul et al. 1990). The data indicate that the three symbiotic bacterial strains that have been isolated from Heterorhabditis family were highly similar to Photorhabdus. The identified bacterial strains were registered on the GeneBank under the accession number KC237382 to P. luminescens HRM1 and KC237383 for the P. luminescens HS1, while the third sequence was identical with P. luminescens HP88. The data of the two symbiotic bacteria which have been isolated from Stinernema family indicate that one of them was identical to X. indica and the second sequence was similar to X. nematophila ATTC19061 16S rDNA gene sequence with the score of 96%.

Fig. 1.

PCR profile of the 16S rDNA for the five bacterial isolates. M the 1 kb ladder. Lanes 1–5 the bacterial strain (lane 1: p.HP88, lane 2: p.RM1, lane 3: p.S1, lane 4: x. Ab, lane 5: x.s2)

The five bacterial strains identified were characterized at the molecular levels using three molecular markers (RAPD, ISSR and SRAP) to determine the genetic polymorphism among them and also to determine the genotype-specific markers for each strain.

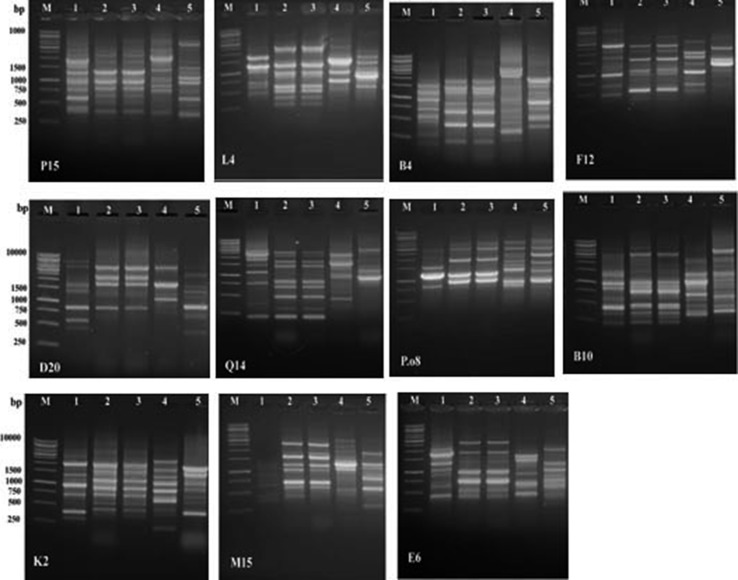

Eleven random RAPD primers were used to detect the genetic polymorphism among these five bacterial strains. All the primers tested resulted in clear bands (Fig. 2). The three Photorhabdus strains generated 126 bands: 93 bands out of them were polymorphic and can be considered as useful bands for the three bacterial isolates with 73.8 polymorphism percentages. The Xenorhabdus strains showed 123 total bands and 76 bands out of the total bands were polymorphic with 54.5% polymorphism (Table 2). The RAPD genotype-specific bands as presented in Table 3 indicate that the three Photorhabdus strains showed 41 genotype-specific markers that represent 44% from the polymorphic band detected and 32.5% from the total band numbers (Tables 2, 3). The highest genotype-specific number was recorded for the bacterial strain P. luminescens HP88 (37 markers) followed by P. luminescens HS1 (2 markers) and P. luminescens RM1 (2 markers). Xenorhabdus strains showed 76 specific markers: 39 markers of them are specific to X. nematophila S2 and 37 for X. indica AB. The genotype-specific markers obtained for Xenorhabdus strains represent 61.7% of the total band number and 100% of the polymorphic bands (Tables 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

RAPD profiles of the five bacterial strains. Lanes 1–3 are Photorhabdus and lanes 4–5 are Xenorhabdus strains. M DNA ladder

Table 2.

Genetic polymorphism among three Photorhabdus and two Xenorhabdus strains as revealed by RAPD, ISSR and SRAP analyses

| Photorhabdus strains | Xenorhabdus strains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAPD | ISSR | SERAP | RAPD | ISSR | SERAP | ||

| Total number of bands | 126 | 95 | 230 | Total number of bands | 123 | 113 | 191 |

| Polymorphic bands | 93 | 67 | 174 | Polymorphic bands | 76 | 85 | 117 |

| Polymorphism % | 73.8 | 70.1 | 75.6 | Polymorphism % | 54.5 | 75.2 | 61.2 |

Table 3.

RAPD genotype-specific markers

| Strain | Marker | Total |

|---|---|---|

| P. luminescens HP88 | L4(1750, 1200, 700), M15(400), P15(1700, 800, 500, 350, 200), E6(1600, 1200, 900, 800, 600, 400), D20(1500, 600, 400), B4(900, 500, 350), P.09(1500), F12(4000, 2400, 700, 500), Q14(4000, 400), K2(2500, 1200, 750, 250), B10(2000, 1400, 1200, 600, 450) | 37 |

| P. luminescens RM1 | K2(100), B10(3000) | 2 |

| P. luminescens HS1 | P15(2000), P.09(5000) | 2 |

| Total | 41 | |

| X. indica AB | M15(1550, 600, 500), P15(2000, 1700, 1500, 1400, 1200,950, 700, 500), E6(1200, 1000, 250), D20(3000, 1750, 1200), B4(3000, 2200, 400, 250), P.09(2000, 1500, 800), F12(3000, 2400, 1700, 700, 500), Q14(4000, 2000, 1750, 600, 450), B10(800, 700, 400) | 37 |

| X. nematophila S2 | L4(1750, 1200, 900, 600,450, 350, 200), M15(2000, 100, 700, 350), P15(3000, 1000, 900, 750, 350, 250, 100), E6(2000, 1600, 900, 500, 400, 350, 150), D20(2000, 1500, 800, 700, 400), B4(900, 700, 650, 500, 450), F12 (3500), Q14(3000), B10(2500, 750) | 39 |

| Total | 76 |

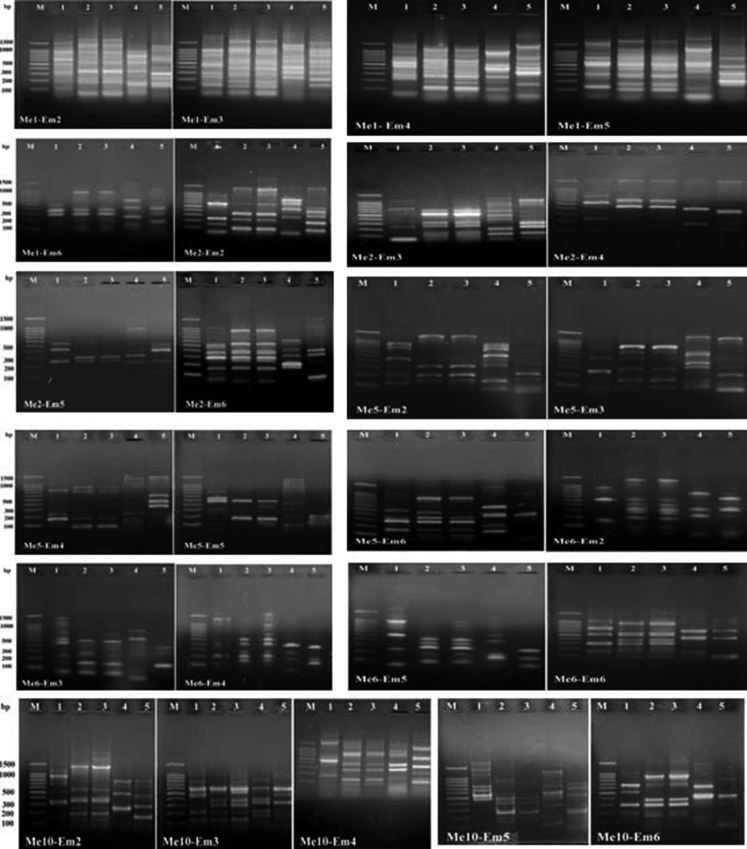

The presence of simple sequence repeats (SSR) in prokaryotes is well documented (Gur-Arie et al. 2000), and some SSRs show extensive length polymorphisms (Yang et al. 2003; Sreenu et al. 2006). Successful use of PCR-based SSR amplification followed by amplicon size determination to analyze the spread of microbial pathogens has been reported for Haemophilus influenzae and Candida albicans (Bretagne et al. 1997; van Belkum et al. 1997). Furthermore, the utility of inter-simple sequence repeat-PCR (ISSR-PCR) assay in the characterization and elucidation of the phylogenetic relationship between the pathogenic and nonpathogenic isolates of Vibrio cholerae was demonstrated (Kumar et al. 2007). They proposed that ISSR-PCR is an efficient tool in phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic genomes in general and diagnostic genotyping of microbial pathogens in particular. A DNA sample representing the five bacterial strains was subjected to PCR analysis using twelve ISSR primers. The primers used show stable and repeatable banding pattern for the strain tested (Fig. 3). Data presented in Table 2 indicate that 95 ISSR bands were generated among the three Photorhabdus strains; 28 bands out of total band numbers were monomorphic bands representing a common band in the genus Photorhabdus and 67 bands which are polymorphic can be considered as useful bands for the three bacterial isolates with 70.1 polymorphism percentages. The primers showed different polymorphism percentages that ranged from 33% for the primer IS3 to 100% for UBC815. The Xenorhabdus strains showed 113 total bands; 85 bands out of the total bands were polymorphic with 75.2% polymorphism (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

ISSR profiles of the five bacterial strains. Lanes 1–3 are Photorhabdus and lanes 4–5 are Xenorhabdus strains. M DNA ladder

The ISSR genotype-specific bands were determined. Data presented in Table 4 show that ISSR marker can distinguish between the different bacterial strains. The three Photorhabdus strains showed 34 genotype-specific ISSR markers that represent 50.7% from the polymorphic band detected and 75.2% from the total band numbers (Table 4). The highest genotype-specific number was recorded for the bacterial strain P. luminescens HP88 (21 markers) followed by P. luminescens RM1 (9 markers) and P. luminescens HS1 (4 markers). Xenorhabdus strains showed 85 specific markers: 45 markers of them are specific to X. nematophila S2 and 40 for X. indica AB. The genotype-specific markers obtained for Xenorhabdus strains represent 75.2% of the total band numbers and 100% of the polymorphic bands (Table 4).

Table 4.

ISSR genotype-specific bands among Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus strains

| Strain | Marker | Total |

|---|---|---|

| P. luminescens HP88 | IS3(1200, 500), IS4(900, 750, 400), IS5(1200), UBC807(1000, 400), UBC808(900, 750, 650, 600, 400, 200), UBC827(3000, 1050), UBC809(800, 600), IS10(700), UBC810(2500, 2200) | 21 |

| P. luminescens RM1 | UBC809(1600), IS10(1400, 1100, 1000), UBC810(2000, 1000, 800, 750, 100), | 9 |

| P. luminescens HS1 | IS5(300),UBC827(1250), IS10(260), UBC810(1250) | 4 |

| Total | 34 | |

| X. indica AB | IS3(3500, 2200, 1200), IS5(400, 300), UBC807(2500, 2000, 1800, 1000, 900, 530, 400), UBC808(360, 250), UBC827(670, 220), UBC809(2000, 1500, 650, 520, 500, 230, 150), IS10(2000, 1100, 900, 700), UBC810(1500, 1250, 1000, 800, 750,100), UBC811(1500, 1350, 1550, 1500, 350, 300, 100) | 40 |

| X. nematophila S2 | IS3(4000, 1800, 1000, 900, 600), IS4(3000, 300, 200, 150), IS5(3500, 1100, 780), UBC815(1900, 750, 350), UBC807(1400, 1200, 800, 500, 150), UBC808(1200, 900, 750,650, 600, 500, 450,350,300), UBC827(1050, 750, 490), UBC809(350, 250, 200), IS10(1400, 600, 550, 300, 250, 150), UBC810(2000, 1550, 350), UBC811(1350, 250) | 45 |

| Total | 85 |

Li and Quiros (2001) reported that the SRAP forward primer preferentially amplified exonic regions and the reverse primer preferentially amplified intronic regions. Therefore, the SRAP technique could detect polymorphisms arising from variations in the length of introns, promoters, and spacers, among both genotypes and species when different forward and reverse primers are randomly combined (Li et al. 2014).

In the present study, twenty-five SRAP combinations of five forward and five reverse primers were used for fingerprinting the five bacterial strains. All the SRAP primer combinations resulted in a scorable and reproducible bands. The data presented in Fig. 4 illustrate the SRAP banding pattern of the five bacterial strains.

Fig. 4.

SRAP profiles of the five bacterial strains. Lanes 1–3 are Photorhabdus and lanes 4–5 are Xenorhabdus strains. M DNA ladder

Data presented in Table 2 indicated that 230 bands were generated among the three Photorhabdus strains: 174 bands out of the total band numbers were polymorphic and can be considered as useful bands for the three bacterial isolates with 75.6 polymorphism percentages. The primer combinations showed different polymorphism percentages. The Xenorhabdus strains showed 191 total bands: 117 bands out of the total bands were polymorphic with 61.2% polymorphism (Table 2).

The SRAP genotype-specific bands were determined. Data presented in Table 5 indicate the possibility of identifying the five bacterial strains based on the SRAP-specific markers. The three Photorhabdus strains showed 69 genotype-specific markers that represent 39.6% from the polymorphic band detected and 30% from the total band numbers (Tables 2, 5). The highest genotype-specific number was recorded for the bacterial strain P. luminescens HP88 (56 markers) followed by P. luminescens HS1 (9 markers) and P. luminescens RM1 (4 markers). Xenorhabdus strains showed 117 specific markers: 45 markers of them are specific to X. nematophila S2 and 72 for X. indica AB. The genotype-specific markers obtained for Xenorhabdus strains represent 61.2% of the total band number and 100% of the polymorphic bands (Tables 2, 5).

Table 5.

SRAP genotype-specific markers

| Strain | Marker | Total |

|---|---|---|

| P. luminescens HP88 | Me1* Em2(750, 700, 500,280), Me1* Em3(1600, 100), Me1* Em4(1500, 1200, 700, 500), Me1* Em5(120), Me1* Em6(420), Me2* Em2(150,50), Me2* Em3(1200, 700), Me2* Em4(800, 600 200), Me2* Em5(650, 500), Me2* Em6(1100, 500, 100), Me5* Em2(800, 600, 100), Me5* Em3(600, 50), Me5* Em4(600), Me5 *Em5(800, 600,300, 250, 100), Me5* Em6(1000, 500), Me6* Em3 (1300, 1100, 700, 200), Me6* Em4(1200), Me6* Em5(800, 600), Me6* Em6(1000), Me10* Em2(1100, 900, 800, 150), Me10* Em3(450), Me10* Em5(1000, 900, 850,600, 500), Me10* Em6(500) | 56 |

| P. luminescens RM1 | Me2* Em5(700), Me10* Em5(800, 150, 100) | 4 |

| P. luminescens HS1 | Me1* Em5(900, 700, 150), Me5* Em3(350), Me5 *Em5(350), Me6* Em4(1600, 600), Me10* Em3(1000), Me10* Em4(500) | 9 |

| Total | 69 | |

| X. indica AB | Me1* Em2(750, 650, 300, 100), Me1* Em3(1300, 1200, 700, 600, 180, 100), Me1* Em4(800, 300), Me1* Em5(120), Me1* Em6(1600, 600, 260, 100), Me2* Em2(800, 600,500 300, 50), Me2* Em3(1200, 600,150), Me2* Em5(900, 300), Me2* Em6(600, 300, 200), Me5* Em2(800, 700, 600, 500, 400, 300, 150), Me5* Em3(500, 400, 350, 300), Me5* Em4(1500, 200, 150), Me5 *Em5(1200, 1000, 900, 850, 800, 700, 600, 500, 350, 300, 1200), Me5* Em6(700, 200), Me6* Em3(900, 700), Me6* Em5(1200, 600), Me6* Em6(180), Me10* Em3(800, 350, 200), Me10* Em4(800,300), Me10* Em5(400, 300), Me10* Em6(1400, 500, 200) | 72 |

| X. nematophila S2 | Me1* Em2(1000, 700, 450, 280), Me1* Em3(80), Me1* Em4(1500, 700, 350), Me1* Em5(300, 250), Me1* Em6(180), Me2* Em2(400, 350, 150, 100), Me2* Em3(100, 300, 220), Me2* Em4(400, 150), Me2* Em5(650, 550), Me2* Em6(350, 100), Me5* Em2(200), Me5* Em4(1600, 700, 600, 500, 250(,Me5 *Em5(150, 100), Me5* Em6(550), Me6* Em3(150), Me6* Em6(1000), Me10* Em2(450, 150), Me10* Em3(1000, 450), Me10* Em4(500, 250), Me10* Em5(800, 700, 200, 150) | 45 |

| Total | 117 |

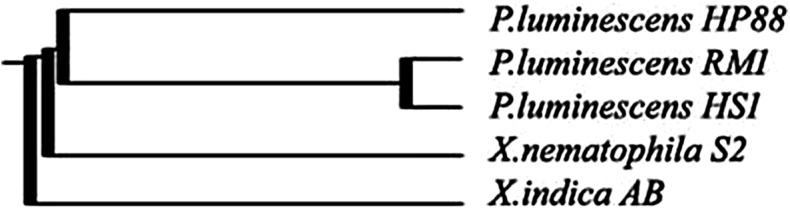

The data obtained from the three molecular markers used were pooled together and were used to construct the phylogenetic tree that shows the genetic relationship among the five bacterial strains. The cluster analysis is divided into three clusters: the first cluster has X. indica AB, the second cluster has the strain X. nematophila S1 while the third cluster is divided into two sub-clusters. The first P. luminescens HRM1 and P. luminescens HS1 are close together and the other sub-cluster has P. luminescens HP88 (Fig. 5). From the cluster analysis, it is clear that the three molecular markers used can distinguish between the five bacterial strains. The Photorhabdus strain was grouped together at the same cluster (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree based on the data obtained from RAPD, ISSR and SRAP analyses

Conclusion

Based on the data obtained from the present study, the three molecular markers (RAPD, ISSR and SRAP) in addition to the 16S rDNA could be efficiently used to identify and characterize the five bacterial strains. The genotype-specific markers were sufficient to distinguish between the different bacterial strains and can be used in the future IBM program that could be built on the use of these strains.

Acknowledgements

The authors express deep sense of gratitude to the staff members of the Genetic Engineering Research Center, Cairo University for all the support, assistance and constant encouragements to carry out this work.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Akhurst RJ. Morphological and functional dimorphism in Xenorhabdus spp., bacteria symbiotically associated with the insect pathogenic nematodes Neoaplectana and Heterorhabditis. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;121:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Akhurst RJ, Boemare NE. Biology and taxonomy of Xenorhabdus. In: Gaugler R, Kaya HK, editors. Entomopathogenic nematodes in biological control. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1990. p. 7590. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi S, Al-Faifi S, Migdadi H, Khan M, El-Harty E, Ammar M. Molecular diversity assessment using sequence related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) markers in Vicia faba L. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:16457–16471. doi: 10.3390/ijms131216457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E, Lipman D. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baloch FS, Kurt C, Arioglu H, Ozkan H. Assaying of diversity among soybean (Glycin max (L.) Merr.) and peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes and DNA level. Turk J Agric For. 2010;34:285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Boemare NE, Akhurst RJ. The genera Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus. In: Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt, editors. The Prokaryotes. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 473–488. [Google Scholar]

- Bretagne S, Costa JM, Besmond C, Carsique R, Calderone R. Microsatellite polymorphism in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 gene of Candida albicans as the basis for a typing system. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1777–1780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1777-1780.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Nordentoft S, Olsen JE. Phylogenetic relationships of Salmonella based on rRNA sequences. J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:605–610. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-2-605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Valle EE, Dolinski C, Barreto EL, Souza RM. Time period between infection of Heterorhabditis baujardi LPP7 (Nematoda: Rhabditida) and soil application of Galleria mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) cadavers on the emergence of infective juveniles. Nematol Bras. 2013;37(1/2):26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers RU. Entomopathogenic nematodes in the European biocontrol market. Commun Agric Appl Biol Sci. 2003;68:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira T, van Reenen CA, Endo A, Tailliez P, Pagès S, Spröer C, Dicks LM. Photorhabdus Heterorhabditis sp. nov., a symbiont of the entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis zealandica. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(Pt 5):1540–1545. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.059840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forst S, Dowds B, Boemare N, Stackebrandt E. Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus spp.: bugs that kill bugs. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1997;51:47–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich-Blair H, Clarke DJ. Mutualism and pathogenesis in Xenorhabdus and Photorhabdus: two roads to the same destination. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64:260–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur-Arie R, Cohen CJ, Eitan Y, Shelef L, Hallerman EM, Kashi Y. Simple sequence repeats in Escherichia coli: abundance, distribution, composition, and polymorphism. Genome Res. 2000;10:62–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim A, Goebel BM, Liesack W, Griffiths M, Stackebrandt E. The phylogeny of the genus Yersinia based on 16S rDNA sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Liu JP. Evaluation of genetic diversity in Piper spp. using RAPD and SRAP markers. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10:2934–2943. doi: 10.4238/2011.November.29.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Dong H, Zhang G, Yu B, Chapman LR, Fields MW. Microbial diversity in water and sediment of Lake Chaka, an athalassohaline lake in northwestern China. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:3832–3845. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02869-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafkas S, Ozkan H, Ak BE, Acar I, Atli HS. Detecting DNA polymorphism and genetic diversity in a wild pistachio germplasm: comparison of AFLP, ISSR and RAPD markers. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 2006;131:522–529. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AR, Sathish V, Nair GB, Nagaraju J. Genetic characterization of Vibrio cholerae strains by inter simple sequence repeat-PCR. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;272(2):251–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MM, Stock SP. A multigene approach for assessing evolutionary relationships of Xenorhabdus spp. (γ-proteobacteria), the bacterial symbionts of entomopathogenic Steinernema nematodes. J Invertebr Pathol. 2010;104(2):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Quiros CF. Sequence related amplified polymorphism (SRAP), a new marker system based on simple PCR reaction: its application to mapping and gene tagging in Brassica. Theor Appl Genet. 2001;103:455–461. doi: 10.1007/s001220100570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Shen JX, Wang TH, Fu TD, Ma CZ. Construction of a linkage map using SRAP, SSR and AFLP markers in Brassica napus L. Sci Agric Sin. 2007;40:1118–1126. [Google Scholar]

- Li QY, Dong SJ, Zhang WY, Lin RQ, Wang CR, Qian DX, Lun ZR, Song HQ, Zhu XQ. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism, an effective molecular approach for studying genetic variation in Fasciola spp. of human and animal health significance. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:403–409. doi: 10.1002/elps.200800411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XY, Li J, Zhao ZJ, Yang F, Fu QW, Liu HS, Wang RY. Sequence-related amplified polymorphism (SRAP) for studying genetic diversity and population structure of plants and other living organisms: a protocol. J Anim Plant Sci. 2014;24(5):1478–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Lu JJ, Wang S, Zhao HY, Liu JJ, Wang HZ. Genetic linkage map of EST-SSR and SRAP markers in the endangered Chinese endemic herb Dendrobium (Orchidaceae) Genet Mol Res. 2012;11:4654–4667. doi: 10.4238/2012.December.21.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets JJ, Hey TD, Fencil Burton KJ, Ni SL, Lang WAE, Aktories K. Insecticidal toxin complex proteins from Xenorhabdus nematophilus structure and pore formation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):22742–22749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.227009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha YK, Lee KY. Oral toxicity of Photorhabdus culture media on gene expression of the adult sweet potato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci. J Invertebr Pathol. 2012;109:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy. The principles and practices of 17 numerical classification. San Francisco: WH Freeman and Co.; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Song HQ, Mo XH, Zhao GH, Li J, Zou FC, Liu W, Wu XY, Lin RQ, Weng YB, Zhu XQ. Electrophoretic detection of genetic variability among Schistosoma japonicum isolates by sequence-related amplified polymorphism. Electrophoresis. 2011;32:1364–1370. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreenu VB, Kumar P, Nagaraju J, Nagarajaram HA. Microsatellite polymorphism across the M. tuberculosis and M. bovis genomes: implications on genome evolution and plasticity. BMC Genom. 2006;7:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Belkum A, Melchers WJ, Ijsseldijk C, Nohlmans L, Verbrugh H, Meis JF. Outbreak of amoxycillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae type b: variable number of tandem repeats as novel molecular markers. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1517–1520. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1517-1520.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YH, Li YP, Zhang Q, Zhang X. Enhanced antibiotic activity of Xenorhabdus nematophila by medium optimization. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:1708–1715. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh J, Petersen C, McClelland M. Polymorphisms generated by arbitrarily primed PCR in the mouse: application to strain identification and genetic mapping. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;20:303–306. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JGK, Kubelik AR, Livak KJ, Rafalski JA, Tingey SV. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucl Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Wang J, Chen YuJ, Dong J, Yao Z, Shen Y, Jin Q, Chen R. Identification and characterization of simple sequence repeats in the genomes of Shigella species. Gene. 2003;322:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Ma B, Luo X, Zheng L, Xu X, Yang Z. Molecular diversity of Auricularia polytricha revealed by inter-simple sequence repeat and sequence-related amplified polymorphism markers. Curr Microbiol. 2008;56:240–245. doi: 10.1007/s00284-007-9067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Qi JM, Fang PP, Su JG, Xu JT, Tao AF. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship of castor germplasm as revealed by SRAP analysis. J Wuhan Bot Res. 2010;1:002. [Google Scholar]

- Zietkiewicz E, Rafalski A, Labuda D. Genome fingerprinting by simple sequence repeat (SSR)-anchored polymerase chain reaction amplification. Genomics. 1994;20:176–183. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]