Abstract

Mammalian cells have evolved specialized mechanisms to sense and repair double-strand breaks (DSBs) to maintain genomic stability. However, in certain cases, the activity of these pathways can lead to aberrant DNA repair, genomic instability and tumorigenesis. One such case is DNA repair at the natural ends of linear chromosomes, known as telomeres, which can lead to chromosome-end fusions. Here, we review data obtained over the past decade and discuss the mechanisms that protect mammalian chromosome ends from the DNA damage response. We also discuss how telomere research has helped to uncover key steps in DSB repair. Last, we summarize how dysfunctional telomeres and the ensuing genomic instability drive the progression of cancer.

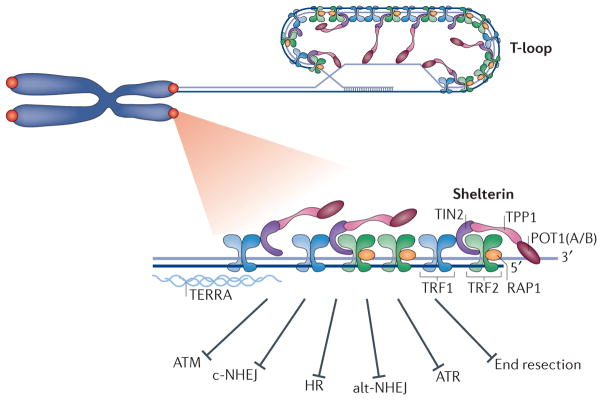

Linear chromosomes pose a challenge to eukaryotic cells. This problem was first recognized by Barbara McClintock and Herman Muller1,2, who postulated that specialized structures named ‘telomeres’ distinguish chromosome ends from sites of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). Since then, extensive research has revealed the composition, structure and function of telomeres (FIG. 1). Mammalian telomeres consist of arrays of TTAGGG repeats that range from 5 kb in human cells to 100 kb in mice, which are polymerized by telomerase, a specialized reverse transcriptase3. Telomeres end with a single-stranded G-rich overhang4,5 that can invade the preceding double-stranded region to generate a special lariat-like structure called the telomere loop or t-loop6,7. Telomere DNA is transcribed by RNA polymerase II into a long non-coding telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA)8. The function of TERRA is not fully understood, but the emerging view is that it functions as a molecular scaffold for proteins that assist in proper telomere function (for a review, see REF. 9).

Figure 1. Overview of telomere composition and function.

Mammalian telomeres are composed of long stretches of TTAGGG repeats that range from 5 kb in human cells to 100 kb in mice and end with a single-stranded 3′ overhang of up to a few hundred nucleotides in length4,5. Telomeric DNA is bound by the specialized shelterin complex, transcribed into a long non-coding telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) and packaged into a t-loop (telomere loop) configuration. Shelterin subunits include TRF1 (telomere repeat-binding factor 1), TRF2, TIN2 (TRF1-interaction factor 2), RAP1 (repressor activator protein 1), TPP1 and POT1 (protection of telomere 1; POT1A and POT1B in mice). The six-subunit complex protects chromosome ends from DNA damage signalling by ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related), and from DNA repair by c-NHEJ (classical non-homologous end joining), alt-NHEJ (alternative non-homologous end joining), HR (homologous recombination) and DNA end resection.

Telomeres are bound by shelterin, a six-subunit protein complex that protects chromosome ends from aberrant activation of the DNA damage response (DDR)10 (FIG. 1). Shelterin recognizes TTAGGG repeats through the binding of its TRF1 (telomere repeat-binding factor 1; also known as TERF1)11 and TRF2 (REFS 12,13) subunits to duplex DNA. TRF1 and TRF2 co-interact with TIN2 (TRF1-interacting nuclear factor 2), which in turn binds the TPP1 (PTOP, PIP1 or TINT1)–POT1 (protection of telomere 1) heterodimer14–18. POT1 is the third DNA-binding component within shelterin. It is recruited to telomeres by interacting with TPP1 and coats the single-stranded part of the TTAGGG repeats with its oligonucleotide/oligosaccharide binding folds19,20. Rodents express two POT1 paralogues — POT1A and POT1B — that are structurally similar yet functionally divergent21,22. RAP1 (repressor activator protein 1) is the sixth and most conserved shelterin component; it is recruited to telomeres by interacting with TRF2 (REFS 23–25). The current view is that shelterin can form as a six-subunit complex as well as subcomplexes lacking TRF1 or TRF2–RAP1 (REFS 14,15,18,26). The telomere proteome comprises additional telomere-associated proteins27–30, including DNA damage factors (Ku, MRN (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1)), nucleases (structure-specific endonuclease subunit SLX4, Apollo), helicases (Bloom syndrome, RecQ helicase-like (BLM), Werner syndrome, RecQ helicase-like (WRN), regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1 (RTEL1)) and chromatin modifiers (α-thalassaemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX)). A key complex that is central for telomere function is the trimeric CST complex, which is composed of the DNA polymerase α (Pol α)–primase accessory factors CTC1, STN1 and TEN1 (REFS 31,32). Interestingly, recent data suggest that in mouse germ cells, a meiosis-specific telomere complex, composed of TERB1 (telomere repeats-binding bouquet formation protein 1), TERB2 and membrane-anchored junction protein (MAJIN), replaces the shelterin complex to facilitate the attachment of telomeres to the inner nuclear membrane33,34.

When shelterin function is compromised, the outcome is rapid telomere deprotection, activation of the DDR leading to cellular death (apoptosis) or irreversible cell cycle arrest (senescence), and, in certain cases, induction of genomic instability. Shelterin function is lost in cells with critically short telomeres, as chromosome ends in these cells lack sufficient binding sites for this protective complex. In other cases, loss of function of shelterin is caused by genetic alterations in components of the complex, leading to alteration in binding and/or function. In this Review, we discuss recent discoveries that have shed light on how chromosome ends are protected by the shelterin proteins to avoid genomic instability, and on how telomere deprotection has been used to identify novel DSB repair factors.

Peeling back layers of end protection

Cells detect DNA breaks with the help of two surveillance pathways, driven by the signalling kinases ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related), which are activated in response to the formation of DSBs and single-strand breaks, respectively (for a review, see REF. 35). DNA damage signalling triggers cell cycle arrest, which allows cells to repair the breaks, if possible, or to undergo senescence or apoptosis. Repair of DSBs involves either the error-free pathway of homologous recombination, or one of the two error-prone, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathways, classical NHEJ (c-NHEJ) or alternative NHEJ (alt-NHEJ) (BOX 1). In addition, DSBs are subject to nucleolytic processing, which is a key step that can influence the choice of repair pathway. During the past two decades, genetic studies have helped to delineate how telomeres use shelterin to silence the DDR.

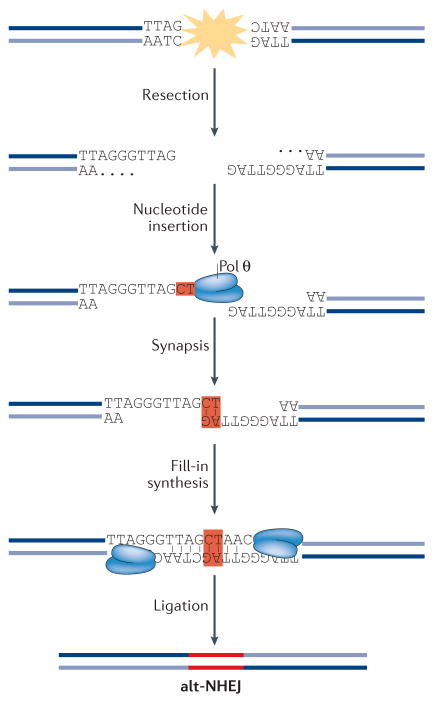

Box 1. Classical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ) versus alternative NHEJ (alt-NHEJ).

Cells use two mechanistically distinct end-joining pathways to repair DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)194,195. C-NHEJ leads to minimal sequence alterations at the repair junctions, whereas alt-NHEJ (also known as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ)) causes extensive deletions (as well as insertions) that scar the break sites following repair (see the figure). C-NHEJ is active throughout the cell cycle and is initiated when the Ku70–Ku80 heterodimer binds to DNA ends with high affinity. Ku then recruits the Ser/Thr kinase DNA-PKcs (DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit) to phosphorylate a number of downstream targets, including the terminal end-processing enzyme Artemis that cleaves single-stranded overhangs, and DNA ligase 4 (LIG4) and the scaffold protein XRCC4, which catalyse the ligation of DNA ends. Alt-NHEJ, which is most active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle, is dependent on signalling by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) and relies on 5′–3′ resection of DNA by MRN (MRE11–RAD50–NBS1) and CtBP-interacting protein (CtIP). Base pairing at the resected ends drives their annealing to promote synapsis of opposite ends of a DSB. Annealed ends are subject to fill-in synthesis by the low-fidelity DNA polymerase θ (Pol θ), which stabilizes the annealed intermediates and promotes end joining, primarily by LIG3. Alt-NHEJ introduces deletions and insertions that scar the break sites following repair. The deletions are caused by extended nucleolytic processing, whereas the insertions result from the activity of Pol θ.

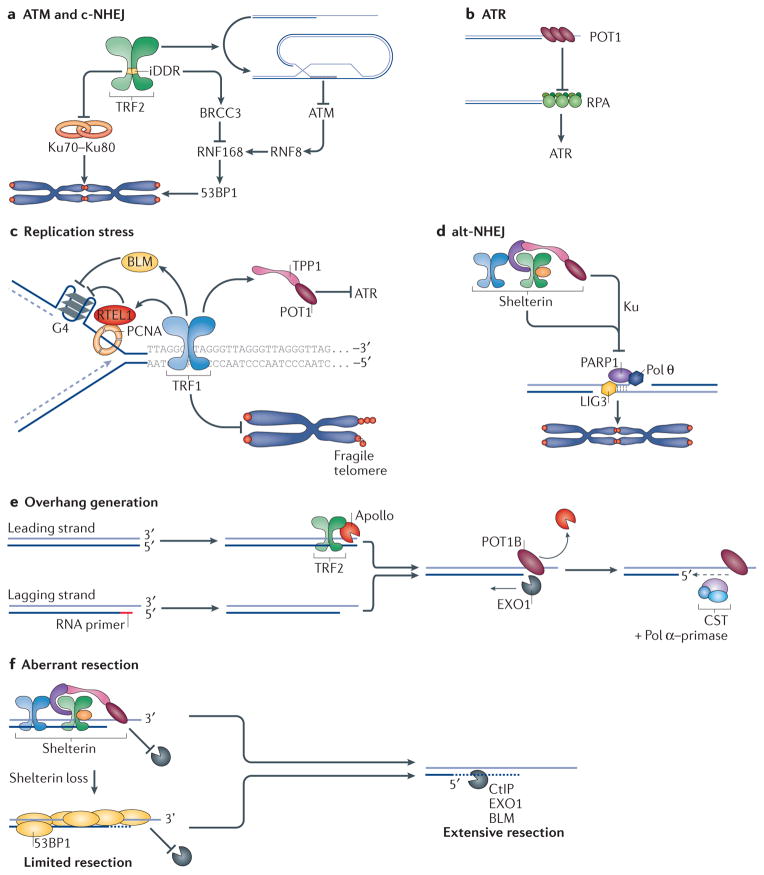

TRF2, the bouncer at the gate

DNA damage signalling by ATM is primarily repressed at telomeres by TRF2 (REFS 36,37). TRF2 inhibition activates ATM, which phosphorylates the downstream effectors Ser/Thr protein kinase CHK2 and p53 (REF. 24), thereby inducing the formation of telomere dysfunction-induced foci (TIFs). These are marked domains of telomere-associated DNA damage factors, including 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1) and the histone variant H2AX38. The underlying mechanism by which TRF2 inhibits ATM-dependent repair pathways is complex and not fully understood. The current view emphasizes two levels of control; the first involves the t-loop configuration, and the second consists of direct inhibition of the ATM signalling cascade (FIG. 2a). TRF2 binding to DNA in vitro stimulates strand invasion, forming structures that resemble t-loops39. Furthermore, the frequency of t-loops in vivo is significantly reduced in cells lacking TRF2, implicating this shelterin subunit in their formation and/or stabilization7. When telomere ends are engaged in a t-loop configuration, they are unlikely to be detected by the MRN complex, which is essential for ATM activation. In addition, TRF2 inhibits ATM signalling directly by inhibiting the kinase itself36, as well as crucial downstream effectors of the ATM pathway40 (FIG. 2a). A motif within TRF2, termed the iDDR (inhibitor of the DDR pathway), inhibits the activity of the E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF168, thereby preventing the accumulation of 53BP1, which is a key effector of ATM40. The two-step mechanism by which TRF2 inhibits ATM activation may be crucial for telomere protection during the S phase of the cell cycle. The progression of the replication fork through telomeric DNA triggers transient unwinding of t-loops and renders chromosome ends susceptible to the DDR. Direct inhibition of the ATM signalling pathway by TRF2 will therefore ensure end protection. Finally, biochemical analysis and atomic force microscopy has highlighted a topological mechanism of TRF2-mediated repression of ATM. Specifically, the wrapping of DNA around the TRFH domain of TRF2 was recently proposed to promote t-loop formation and inhibit ATM signalling39,41.

Figure 2. How shelterin protects telomeres.

a | TRF2 (telomere repeat-binding factor 2) represses ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) signalling and classical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ). TRF2 promotes the formation of the protective telomere loop (t-loop) structure, which hides chromosome ends from ATM and c-NHEJ. In addition, TRF2 inhibits 53BP1 (p53-binding protein 1) accumulation by blocking RNF168-mediated ubiquitylation by activating the deubiquitylase BRCC3 (BRCA1/BRCA2-containing complex, subunit 3). Last, TRF2 blocks the dimerization of the Ku complex, thereby preventing the activation of c-NHEJ. b | POT1 (protection of telomere 1) represses ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related) signalling by competing with RPA (replication protein A) for single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding at telomeres. c | TRF1 inhibits ATR activity during telomere replication with the help of TPP1–POT1. TRF1 also counteracts replication fork stalling at telomeric secondary DNA structures (such as quadruplex DNA (G4)) with the help of RTEL1 (regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1) and BLM (Bloom syndrome, RecQ helicase-like), thereby protecting against telomere fragility. RTEL1 is recruited to replicating telomeres by interacting with PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen). d | Alt-NHEJ (alternative-NHEJ), which is dependent on DNA ligase 3 (LIG3), PARP1 (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1) and DNA polymerase θ (Pol θ), is repressed in a redundant manner by shelterin and the Ku70–Ku80 complex. e | The generation of telomere 3′ overhang involves TRF2-dependent recruitment of the nuclease Apollo to resect double-stranded ends. Leading and lagging ends are then resected by EXO1 (exonuclease 1) to generate long single-stranded overhangs, which are subsequently filled in by Polα–primase and the CST (CTC1–STN1–TEN1) complex. f | Aberrant resection of uncapped telomeres is carried out by the enzymatic machinery that processes double-strand breaks (DSBs)—the nucleases CtIP (CtBP-interacting protein) and EXO1 and the helicase BLM — and is repressed redundantly by shelterin and 53BP1. iDDR, inhibitor of the DNA damage response.

The struggle to keep ends apart

The most deleterious outcome of telomere dysfunction is the formation of chromosome end-to-end fusions, resulting in dicentric chromosomes, which can lead to breakage–fusion–bridge cycles and induce extensive chromosomal instability. Mammalian cells have evolved sophisticated mechanisms to prevent such events from occurring. The major factor suppressing chromosome end-to-end fusions is TRF2. When telomeres are depleted of TRF2, they become substrates for c-NHEJ24,42. Artificial tethering of TRF2 to non-telomere loci inhibits break repair, suggesting that TRF2 is both necessary and sufficient to suppress c-NHEJ43. TRF2 forms a stable 1:1 complex with its interacting partner RAP1 (REFS 44,45), and RAP1 protein is rapidly destabilized upon deletion of TRF2 (REF. 24). Interestingly, tethering of RAP1 to telomere DNA in cells lacking TRF2 was reported to reduce the frequency of telomere fusions46. However, depletion of RAP1 from human and mouse telomeres is not sufficient to trigger c-NHEJ25,47,48. A recent study provides a plausible explanation for the contrasting data by suggesting that RAP1 provides a redundant mechanism to block c-NHEJ when the function of TRF2 is partially compromised41.

Paradoxically, components of the c-NHEJ pathway, most notably the Ku70–Ku80 complex, are constitutively present at telomeres49. Ku has a crucial role in protecting telomeres in human cells, and its depletion leads to rapid deletion of telomeric repeats50. By contrast, deleting Ku in mice does not trigger major telomeric defects51,52, hinting at alternative solutions to achieve telomere protection in rodents. Nevertheless, the strong impact of Ku depletion on telomere stability in human cells raises the obvious question of how TRF2 is able to disengage Ku without compromising telomere stability (FIG. 2a). A possible mechanism invokes a recently described interaction between TRF2 and the α5 region of Ku70, which prevents Ku70–Ku80 heterotetramerization53. The TRF2–Ku interaction is thought to block the ability of Ku70–Ku80 to tether opposite DNA ends, which could explain why Ku70–Ku80 association with functional telomeres does not unleash c-NHEJ.

Intriguingly, recent reports suggest that during mitosis, telomeres are highly susceptible to c-NHEJ-mediated fusion54–56. Mitotic cells attenuate c-NHEJ globally by preventing the phosphorylation of RNF8 and 53BP1 by mitotic kinases such as Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1)55. When this regulation is bypassed, telomeres are fused in an Aurora kinase B-dependent manner. These data corroborate a previous report showing that prolonged mitotic arrest leads to telomere uncapping following the eviction of TRF2 from telomeres, in a process that is dependent on Aurora kinase B54. Future work is likely to shed light on telomere protection in mitosis and reveal why mammalian cells opt for a global shutdown of c-NHEJ, as opposed to simply configuring an extra layer of protection at telomeres.

Blocking ATR signalling

The activity of ATR at telomeres is primarily repressed by POT1. Deleting POT1, or blocking its recruitment to telomeres by inhibiting TPP1 or TIN2, induces the formation of ATR-dependent TIFs37,57–60. POT1 binds to telomeric single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), thus preventing the recruitment of RPA (replication protein A), which is a crucial factor for the activation of ATR61 (FIG. 2b). Although POT1 affinity for ssDNA does not exceed the binding affinity of RPA, it has been proposed that the increased local concentration of POT1 at telomeres excludes RPA binding59,60. An alternative model for POT1-mediated inhibition of ATR invokes a cell cycle-regulated RPA-to-POT1 switch mediated by hnRNPA (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A) and TERRA62. According to this model, accumulation of hnRNPA at replicated telomeres promotes the displacement of RPA and the subsequent recruitment of POT1. ATR activation in S phase is also inhibited, by TRF1, which is dedicated to counteracting replication defects at telomeres63 (FIG. 2c). Notably, tethering of TPP1–POT1 to telomeres lacking TRF1 is sufficient to inhibit the TIF response, suggesting that ATR inhibition by TRF1 is dependent on the recruitment of TPP1 and POT1 to telomere DNA64.

A joint effort to suppress alt-NHEJ at chromosome ends

Early evidence for the activation of the alt-NHEJ pathway at mammalian telomeres emerged from the analysis of telomerase-deficient mice. Specifically, chromosome end-to-end fusions following telomere attrition were evident even when core components of the c-NHEJ pathway (DNA ligase 4 and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs)) were deleted65. These experiments hinted that alt-NHEJ could be responsible for processing dysfunctional telomeres in the early stages of tumorigenesis. Analysis of telomere fusion junctions in human tumours revealed hallmarks of alt-NHEJ repair — frequent microhomologies and extensive deletions66–68 — further implicating this error-prone repair pathway as operating at dysfunctional telomeres. Genetic manipulation of shelterin in mouse cells indicated that alt-NHEJ is repressed in a redundant manner69–71. Specifically, ligase 3-mediated telomere fusions were maximally observed when the shelterin complex was completely depleted in Ku70–Ku80 deficient mouse cells69 (FIG. 2d). The mechanism by which redundant suppression of alt-NHEJ is achieved has not been fully established. It is possible that the activity of alt-NHEJ is dependent on signalling by both ATM and ATR, which manifests when the entire shelterin complex is lost. In agreement with this idea, co-depletion of TRF2 and TPP1 — which activate the two kinases, respectively — is sufficient to trigger efficient alt-NHEJ activity70. Similarly, the mechanism by which Ku inhibits alt-NHEJ remains unknown. It has been proposed that Ku has a higher binding affinity to DSBs than PARP1 (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1) and could therefore block alt-NHEJ by repressing PARP1-mediated signalling72,73. Alternatively, Ku might exert its effect by inhibiting 5′ end resection74,75, which is a prerequisite for alt-NHEJ-mediated repair76.

Polishing the end: the art of making overhangs

Telomere ends are subject to two forms of nucleolytic processing, each of which is carried out by independent machineries and regulated differently (FIG. 2e). Following telomere replication, physiological processing of telomere ends generates a 3′ overhang, a crucial structure for telomere protection. This is mediated by a number of factors, including the shelterin subunits TRF2 and POT1B (in mice)21,22,77,78. TRF2 recruits the Apollo nuclease to resect blunt leading-strand ends and create short overhangs, whereas lagging-strand overhangs result from the removal of the RNA primer from the terminal Okazaki fragment78,79. Subsequently, a long-range resection step is carried out by EXO1 (exonuclease 1), which acts on both leading and lagging strands and transiently elongates the overhang77. Finally, overhang length is fine-tuned to an optimal length (~50–300 nucleotides80) with the help of the CST complex, which, in the case of mouse telomeres, is recruited by POT1B to assist during fill-in synthesis77. It is important to note that the genetic analysis of 3′ overhang generation was primarily carried out in mouse cells, and whether human POT1 functions similarly to mouse POT1B remains to be determined.

In addition to the aforementioned physiological processing of telomeres, dysfunctional telomeres are subject to aberrant degradation. Hyper-resection of uncapped telomeres is inhibited by shelterin and by 53BP1, which is a general repressor of DNA end resection at DSBs. Deletion of TRF2 in 53BP1-null cells leads to an extended telomere overhang, mediated by ATM and dependent on the endonuclease CtIP (CtBP-interacting protein)81. A more substantial resection takes place following the deletion of both TRF1 and TRF2 and the creation of shelterin-free telomeres in 53BP1-deficient cells69 (FIG. 2f). The unmitigated resection of shelterin-free telomeres is executed by CtIP and EXO1 and is aided by the helicase BLM69.

How the replication machinery navigates TTAGGG repeats

TTAGGG repeats are prone to forming stable secondary structures (including quadruplex (G4) DNA)82 that challenge the replication machinery as it progresses through telomeric DNA. Among the various shelterin subunits, TRF1 has a major role in assisting the semi-conservative replication of telomeres63,83 (FIG. 2c), and its function is similar to that of the fission yeast orthologue, Taz1 (REF. 84). Deletion of TRF1 from mouse cells induces the formation of fragile telomeres63, a phenomenon that is reminiscent of fragile sites and attributed to DNA replication defects. The protective function of TRF1 is achieved with the help of two helicases, RTEL1 and BLM, which unwind spurious secondary structures and allow faithful duplication of telomeres63. The function of RTEL1 during telomere replication is mediated by an interaction with the replication clamp PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen). Inhibiting the RTEL1–PCNA interaction increases the incidence of replication fork stalling and telomere fragility85. BLM is recruited to telomeres by direct binding to TRF1 and suppresses telomere fragility64,86. Studies have also implicated WRN, another RecQ helicase, in facilitating lagging-strand telomere synthesis87,88, although WRN does not function in the same pathway as TRF1 (REF. 63). A parallel pathway that assists in the replication of telomeres is executed by CST. Inhibition of individual CST components compromises replication fork restart and leads to telomere fragility89,90. The activity of CST is independent of TRF1 (REF. 89), and the complex functions by assisting Pol α–primase activity at telomeres. Last, TRF2 is also thought to facilitate telomere replication by relieving topological constraints that would otherwise hinder replication-fork progression91.

We currently know many of the players that assist telomere replication and counteract telomere fragility, but the dynamic interplay between the different factors assisting the replisome to progress through telomere DNA is unknown. In addition, the nature of the fragile aberrancy itself, and whether it is the result of altered packaging of the chromatin or actual DNA breaks and chromatin gaps, remains a mystery that in the future may be solved by super-resolution microscopy.

Homologous recombination at telomeres: keeping up with the neighbours

The activity of the homologous recombination pathway at telomeres may seem to be less harmful than that of NHEJ, but it can affect cellular survival when it alters telomere length. Homologous recombination at telomeres manifests in three major forms: exchange of sequence between sister (chromatid) telomeres (telomere sister chromatid exchange (T-SCE)), aberrant excision of t-loops (t-loop homologous recombination), and recombination that leads to alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT).

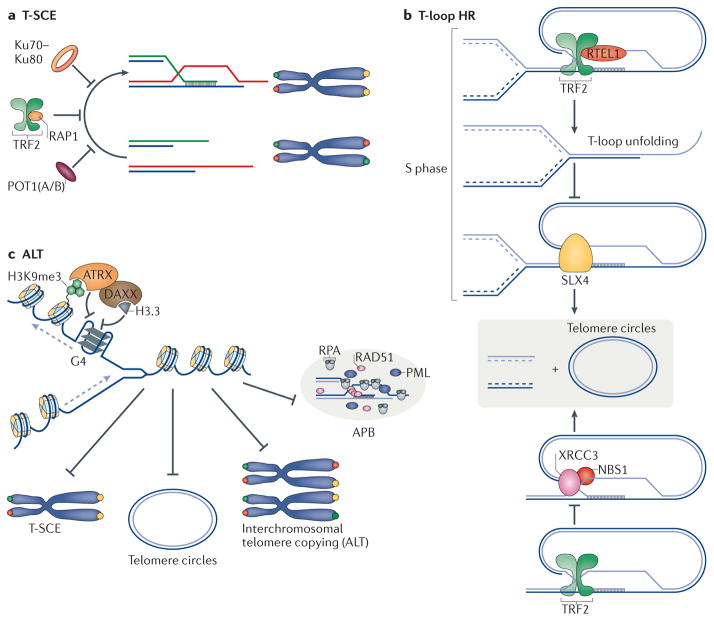

T-SCE has detrimental consequences when an unequal exchange happens, in which case a daughter cell inherits a short telomere and suffers the deleterious impact of telomere uncapping. Loss-of-function analysis in mouse cells revealed that shelterin contributes to the repression of T-SCE together with the Ku complex, which is a general repressor of recombination in mammalian cells92 (FIG. 3a). Depletion of TRF2, RAP1 or POT1 in the context of Ku70–Ku80 complex deficiency stimulates exchange of sequences between telomeres on sister chromatids69,93,94. The mechanism by which these factors inhibit T-SCE is unknown. With regards to POT1, it is conceivable that its binding to telomere ssDNA counteracts the loading of homologous recombination factors — RPA and, subsequently, RAD51 — thereby inhibiting recombination. RAP1 and TRF2 possibly stabilize the telomeric double-stranded DNA (dsDNA)–ssDNA junction and block strand invasion during homologous recombination. Consistent with this idea, in vitro studies indicate that TRF2 has a greater preference for binding to junction sites when bound to RAP1 (REF. 95).

Figure 3. The three facets of telomere homologous recombination: T-SCE (telomere sister chromatid exchange), t-loop (telomere loop) homologous recombination and ALT (alternative lengthening of telomeres).

a | Exchange of sequence between sister chromatid telomeres (marked in red and green) is inhibited by RAP1 (repressor activator protein 1), POT1 (protection of telomere 1) and Ku70–Ku80. b | T-loop homologous recombination is blocked by TRF2 (telomere repeat-binding factor 2). TRF2 recruits RTEL1 (regulator of telomere elongation helicase 1) during S phase to unwind the t-loop and therefore protect it from being cleaved by structure-specific endonuclease subunit SLX4. In addition, TRF2 inhibits t-loop excision by inhibiting the activity of NBS1–XRCC3 (Nijmegen breakage syndrome 1–X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 3). c | Telomere repeats have the propensity to form stable quadruplex (G4) DNA structures, which would impede replication fork progression. It has been proposed that ATRX (α-thalassaemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked) unwind G4 DNA, enabling the deposition of histone H3.3 and ultimately assisting replication fork progression. The activity of ATRX at telomeres inhibits various ALT (alternative lengthening of telomeres) phenotypes including T-SCEs, formation of telomere circles, intrachromosomal telomere recombination and formation of APBs (ALT-associated promyelocytic leukaemia nuclear bodies). DAXX, death domain-associated protein; HR, homologous recombination; PML, promyelocytic leukaemia; RPA, replication protein A.

Aberrant telomere homologous recombination leads to t-loop excision owing to the activity of DNA repair protein XRCC3, NBS1 and SLX4 (FIG. 3b). The t-loop configuration poses a challenge to the replication machinery, as it needs to be unfolded for the replication fork to progress through telomeres, otherwise it could be excised. In addition to promoting t-loop formation, TRF2 protects t-loops from illegitimate homologous recombination. TRF2 recruits RTEL1 to unwind t-loops in S phase96. Deleting RTEL1 or inhibiting its interaction with TRF2 allows SLX4-mediated t-loop excision, resulting in the formation of double-stranded telomere circles (t-circles) and rapid telomere loss96,97. TRF2 also protects the t-loop from XRCC3- and NBS1-mediated cleavage98,99. Notably, telomere trimming by XRCC3 occurs in normal cells that possess long telomeres, including in the male germ line100,101. This mechanism has been proposed to provide an additional layer of telomere length regulation, although how it is kept in check to avoid rampant telomere shortening remains elusive.

ALT is activated in a subset of human tumours that lack telomerase activity102 to maintain the length of the telomere repeats103. Telomeres maintained by ALT typically cluster in ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs)104, have increased expression of TERRA105 and display elevated levels of T-SCE106. A hallmark of ALT is recombination between telomeres on separate chromosomes, which was demonstrated experimentally by interchromosomal copying of a telomere-embedded neomycin tag103. ALT telomeres are highly heterogeneous in length107 and are littered with non-canonical repeats, probably owing to recombination with subtelomeric regions108. Survival of ALT cells is compromised when homologous recombination factors (RAD51, MRN, RAD9, RAD17, RPA and others) are inhibited, confirming their dependency on ALT for telomere maintenance (for a review, see REF. 109).

What triggers ALT and why it is activated in a subset of tumours remains unknown. A strong candidate is the histone chaperone ATRX, which is mutated in a large majority of cells and tumours that exploit the ALT pathway110,111. Reintroducing ATRX into ALT cells suppresses T-SCE, APB and c-circle formation, and inter-chromosomal telomeric recombination112,113 (FIG. 3c). ATRX is part of the SWI/SNF family of ATP-dependent helicases114 and associates with chromatin by binding to sites of histone H3 Lys9 trimethylation (H3K9me3), which are enriched at telomeric DNA115. ATRX also interacts with the histone chaperone DAXX (death domain-associated protein), allowing the deposition of the histone variant H3.3 at repetitive sequences of telomeres and pericentromeres116,117. The mechanism by which ATRX protects TTAGGG repeats from aberrant recombination remains unclear. However, several lines of evidences suggest that it may relate to telomere replication. First, in vitro studies indicate that ATRX binds to and unwinds G4 DNA118. Second, ATRX-deficient ALT cells accumulate increased levels of RPA at telomeres117,119. Last, re-expression of ATRX in ALT cell lines reduces the frequency of replication fork stalling112. Taken together, these studies suggest that both the helicase-unwinding activity of ATRX and the histone chaperone properties of the ATRX–DAXX complex are likely to counteract telomere recombination by resolving stable secondary structures that would otherwise impede fork progression. It is important to emphasize that ATRX depletion by itself is not sufficient to induce ALT112,113, indicating that additional genetic alteration(s) are necessary. Interestingly, deletion of the gene encoding the histone chaperone ASF1A is sufficient to trigger ALT-like phenotypes in telomerase-positive cells120, and binding of the nucleosome-remodelling deacetylase (NuRD) complex to variant repeats found at telomeres in ALT cells creates a permissive environment for recombination121. Such observations reinforce the notion that alteration in chromatin status renders telomeres conducive to homologous recombination. In addition to chromatin environment, the presence of TERRA–telomeric DNA hybrids was proposed to affect ALT — reduced levels of these RNA–DNA hybrids leads to a significant reduction in homologous recombination-mediated telomere elongation105.

In order for ALT telomeres to engage in interchromosomal recombination, they must first disengage from their cohered sister chromatid and move across the nucleus to meet a telomere on another chromosome. ATRX was proposed to regulate this choice between inter- and intratelomeric recombination. In the absence of ATRX, cohesion between sister telomeres persists, prompting an increase in T-SCE122. In addition, HOP2 (homologous-pairing protein 2 homologue), a protein that is normally required for synapsis of meiotic chromosomes, was recently shown to promote rapid and directional movement of telomeres over micrometre distances before their synapsis with recipient telomeres during ALT123.

Using telomeres to discover DDR genes

The realization that inhibition of shelterin activity marks telomeres as sites of DSBs provides an opportunity to interrogate various aspects of the DDR using telomeres as an experimental system. As discussed above, removal of particular shelterin components activates specific DNA damage signalling pathways and repair mechanisms. Accordingly, shelterin manipulation provides a tractable system that has been used to gain insight into the mechanistic basis of DSB repair in mammalian cells.

Ingredients to make sticky ends

Different approaches have been used over the years to isolate factors that bind to functional as well as dysfunctional telomeres. A quantitative telomeric chromatin isolation protocol (QTIP) was applied to identify differences in telomeric chromatin composition between cells with functional telomeres and cells with telomeres depleted of TRF2 and POT1 (REF. 28). In a similar approach, proteomics of isolated chromatin segments (PICh)27 was used to compare functional telomeres to those rendered dysfunctional following the removal of TRF2 (REF. 29). These approaches confirmed that dysfunctional telomeres are recognized as site of DNA damage and recruit the same repair factors that are associated with DSBs at other sites in the genome. Moreover, these methods and others helped to identify novel factors that contribute to the cellular response to telomere dysfunction. For instance, the Polycomb protein Ring1b was found to promote NHEJ at TRF2-depleted telomeres29; a genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) screen identified factors (such as RNF8) that mediate the response to telomere dysfunction124; and isolation of TERRA-interacting proteins led to the identification of a Lys-specific demethylase (LSD1) as a factor that binds to dysfunctional telomeres and stimulates the nuclease activity of MRE11 (REF. 125).

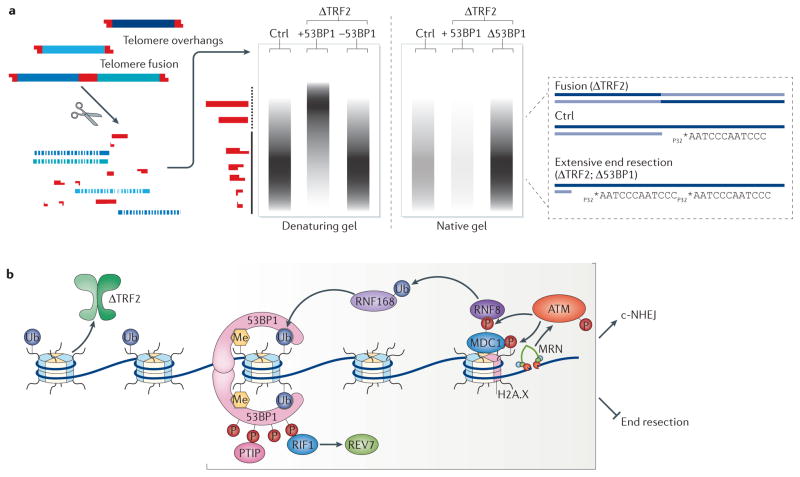

Resecting DSBs — the way it’s done at telomeres

DSB end resection is a crucial processing step that influences DSB repair pathway choice and can commit cells to repairing the break by homologous recombination. The underlying basis of end resection is a subject of intense investigation, and experiments carried out using dysfunctional telomeres have contributed to our understanding of key regulatory steps. 53BP1 is central to the process of DSB resection in mammalian cells. A seminal publication in 2010 reported that the loss of 53BP1 rescues embryonic lethality associated with loss of BRCA1 (breast cancer type 1 susceptibility protein)126,127. This phenotype was due to the reactivation of homologous recombination, which was in turn attributed to the restoration of 5′ end resection upon co-depletion of 53BP1 and BRCA1. DNA end resection at genome-wide DSBs is typically assessed by measuring the accumulation of RAD51 and phosphorylated RPA126. A more accurate measurement can be achieved by analysing telomeres. In that respect, the role of 53BP1 in end resection was confirmed in a direct manner by analysing dysfunctional telomeres, in which the length of ssDNA can be accurately quantified using native gels (FIG. 4a). Specifically, depleting 53BP1 in TRF2-deficient cells blocks telomeres fusions by c-NHEJ and leads to increased end resection81,128. The identification of 53BP1 as a key regulator for resection triggered a race to highlight downstream effectors, and the first to be identified was the 53BP1 partner, RIF1 (RAP1-interacting factor 1)129. Loss of RIF1 in TRF2-null cells lead to an increase in overhang length at telomere termini, and epistasis analysis confirmed that RIF1 and 53BP1 function in the same pathway129 (FIG. 4b). Interestingly loss of RIF1 in the context of shelterin depletion yielded less resection than 53BP1 loss, implying that RIF1 is unlikely to be the only downstream effector of 53BP1 (REF. 129). Subsequently, PAX-interacting protein 1 (PTIP) was identified as a second 53BP1-binding partner and a potential regulator of 5′ end resection. Deleting PTIP, or inhibiting its binding to 53BP1, delays the appearance of fusions in TRF2-null cells130, presumably owing to increased telomere end resection130. Uncovering the role of RIF1 (REFS 129,131–133) and PTIP130 in DSB processing brings us a step closer to understanding the molecular basis of end resection, and further investigation will uncover downstream factors. The first hints were provided by an RNAi screen for genes that mediate the response to TRF2 depletion134. This approach revealed REV7 (also known as MAD2L2) as a key inhibitor of end resection downstream of RIF1 (REF. 134).

Figure 4. Telomeres as a tool to investigate DNA end resection and classical non-homologous end joining (c-NHEJ).

a | An overview of the assay to monitor c-NHEJ and DNA end resection at telomeres. Southern blot analysis allows the visualization of telomere fusion events. Genomic DNA is cleaved with frequently cutting restriction enzymes, resolved on a denaturing gel and hybridized with a radiolabelled telomere probe. As TTAGGG repeats are not cut by restriction enzymes, they are resolved according to their length (in range of the solid vertical line). Telomere fusions that occur following telomere repeat-binding factor 2 (TRF2) depletion are delineated as slow-migrating restriction fragments (dotted vertical line). Inhibition of factors that promote end joining, one example being p53-binding protein 1 (53BP1), prevents the accumulation of these long restriction fragments. This assay can be adjusted to quantify the length of the 3′ overhang, which is generated by 5′ end resection. Specifically, in-gel hybridization is carried out using a radiolabelled telomere probe in native conditions, in which the probe only hybridizes to the terminal single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) telomere overhang. The overhang signal in the native gel is quantified and normalized to the total telomeric DNA. Depletion of factors, including 53BP1 and RAP1-interacting factor 1 (RIF1), that block end resection will lead to excess overhang signal and can be readily examined with this assay. b | A schematic representing key players that promote c-NHEJ and block DNA end resection, focusing on factors that were studied in the context of dysfunctional telomeres in TRF2-deficient cells. Double-strand break (DSB) sensing by the MRE11–RAD50–NBS1 (MRN)196–198 complex triggers a signalling cascade by recruiting autophosphorylated ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM)37. ATM then phosphorylates the histone variant H2A.X at Ser139 (REF. 197), which recruits MDC1 (mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein 1) to sites of breaks199. The phosphorylation of MDC1 by ATM leads to the sequential recruitment of the E3 ubiquitin ligases RNF8 (REF. 124) and RNF168. One substrate of RNF168 is H2AK15 (histone 2A Lys15), which, together with mono- and dimethylated H4K20, serves as a platform to recruit 53BP1 (REFS 128,200), which then recruits the effector proteins RIF1 (RAP1-interacting factor 1)129 and PTIP (Pax transactivation domain-interacting protein)130, both of which bind to phosphorylated 53BP1. RIF1 functions in part by recruiting REV7 (also known as MAD2L2) to sites of breaks, where it inhibits end resection134.

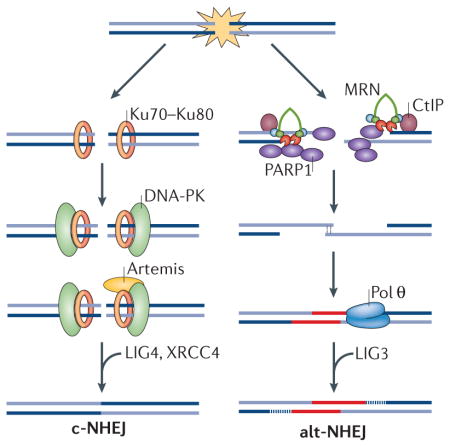

A promiscuous polymerase for a sloppy repair pathway

The robust fusions observed in shelterin-free and Ku70–Ku80-deficient cells enabled investigation of the basis of the increased mutagenicity of alt-NHEJ. Using deep sequencing, non-TTAGGG nucleotide insertions were identified at the junction between two fused telomeres135 (FIG. 5). Such random insertions had previously been identified in other cells in which alt-NHEJ is active136 and provide a molecular signature for this repair pathway. To identify the enzymatic activity responsible for these insertions, a number of low-fidelity DNA polymerases were inhibited in shelterin-free, Ku80-null cells. This led to the identification of the translesion DNA polymerase Pol θ137 as a key alt-NHEJ factor that catalyses the addition of random nucleotides at fusion junctions135 and stimulates the joining of opposing ends of a broken DNA138 (FIG. 5). Depletion of mammalian Pol θ hinders alt-NHEJ at uncapped telomeres, blocks non-reciprocal chromosomal translocations in mouse embryonic stem cells135 and inhibits repair of endonuclease-induced DNA breaks138–140. The function of this translesion polymerase is conserved in Drosophila melanogaster141 and Caenorhabditis elegans142. Notably, Pol θ inhibition in mammalian cells was marked by an increase in homologous recombination135,139, indicating that the erroneous polymerase potentially influences the choice of DSB repair pathway in S phase, when both homologous recombination and alt-NHEJ are most active76.

Figure 5. The mechanism by which DNA polymerase θ (Pol θ) promotes alternative non-homologous end joining (alt-NHEJ).

Sequence analysis of shelterin-free telomeres in Ku-deficient cells identified random nucleotide insertions at telomere fusion junctions. Subsequent genetic studies identified Pol θ as a key alt-NHEJ factor that promotes the joining of dysfunctional telomeres. Following double-strand break (DSB) formation or telomere uncapping, DNA ends are resected to create short 3′ overhangs. On the basis of in vitro experiments, genetic studies and sequence analysis of fusion junctions, Pol θ seems to be capable of extending the 3′ single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) using a combination of template-dependent as well as template-independent activities, the latter potentially mediated through a snap-back intermediate. The incorporation of random nucleotides as sites of breaks is predicted to increase the level of microhomology, thereby promoting the synapsis of opposite ends of a DSB. Annealed intermediates are then subject to fill-in synthesis by Pol θ, a step that would stabilize the duplexed DNA. Ultimately, the DNA is joined by DNA ligase 3.

Pol θ is overexpressed in several human cancers143,144, especially those with homologous recombination deficiency139. Interestingly, depletion of Pol θ in BRCA-mutant tumour cells resulted in significant accumulation of chromosomal aberrations and unrepaired breaks, and compromised cellular survival135,139. Given the increased mutagenicity of alt-NHEJ, it is tempting to speculate that this compensatory mechanism shapes the genome of homologous recombination-defective cancers and therefore influences tumour progression and resistance to therapy.

Telomeres gone bad

Alterations in the activity of telomere-associated proteins are important factors in the onset of human diseases. Dyskeratosis congenita, the prototypical telomere biology disorder (TBD), is caused by mutations in genes involved in telomere length regulation. To date, known mutations causing dyskeratosis congenita have been found in telomerase genes (telomerase RNA template component (TERC) and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)), the TERC-regulating gene H/ACA ribonucleoprotein complex subunit 4 (also known as dyskerin), and the genes encoding the shelterin component TIN2 and the helicase RTEL1, as well as in TCAB1 (also known as WRAP53), NOP10 and NHP2 (REFS 145–154). Dyskeratosis congenita patients have critically short telomeres and display a plethora of symptoms that range from impaired tissue regeneration capacity to cognitive defects. Severe variants of dyskeratosis congenita include Hoyeraal–Hreidarsson syndrome and Revesz syndrome. Less clinically severe variants, such as subsets of apparently isolated aplastic anaemia or pulmonary fibrosis, have also been recognized as TBDs. The genetic basis of TBDs, as well their clinical manifestations and implications, have recently been discussed in an excellent review155. Here, we focus exclusively on how alterations in telomere length and in telomere-associated proteins affect genomic stability and have an impact on cancer development.

The good the bad and the ugly: telomeres and cancer

In certain types of cancer, telomere dysfunction is considered to be a key trigger for chromosomal instability and a promoter of tumorigenesis (FIG. 6a). Rapid proliferation of pre-neoplastic cells leads to gradual telomere shortening, which ultimately triggers a DDR, inducing cellular senescence and/or apoptosis. This illustrates the tumour suppressor function of telomere shortening that limits the proliferative potential of cancer cells156–158. It is estimated that the accrual of five dysfunctional telomeres in a cell is sufficient to elicit a DDR and induce senescence159. Despite losing their end protection, telomeres in senescent cells remain non-fusogenic, and it has been reasoned that this is due to the retention of few molecules of TRF2 that block end joining160. Inactivation of p53 and/or RB pathways allows cells to bypass senescence, leading to telomere attrition and formation of dicentric chromosomes. This is known as telomere crisis, and it is estimated that ~50% of chromosome end-to-end fusions are completely devoid of TTAGGG repeats161. Although most cells succumb to telomere crisis, rare survivors reactivate telomerase (or engage ALT) to replenish telomere repeats and proliferate indefinitely.

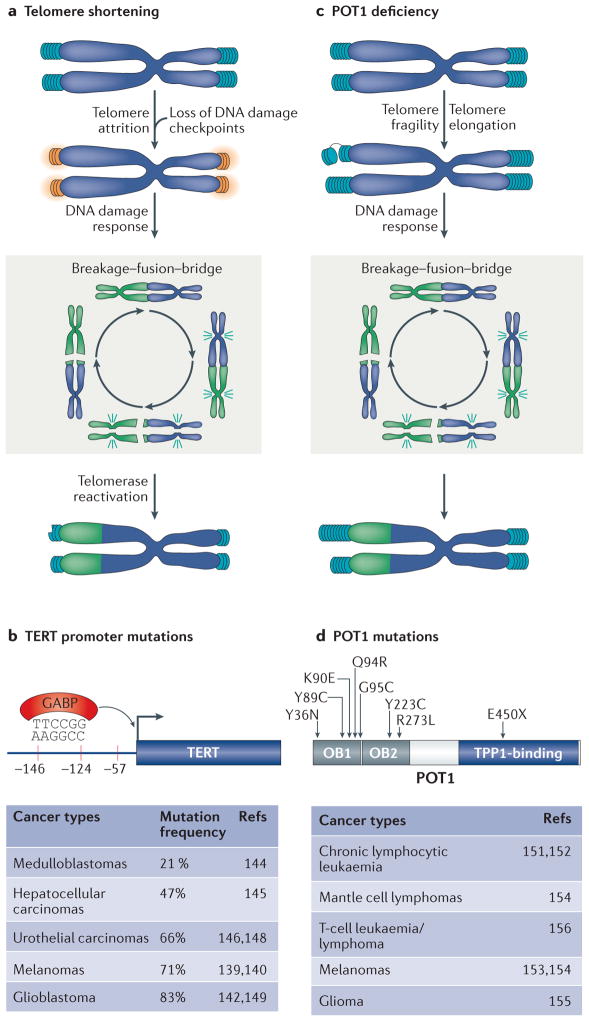

Figure 6. Two independent pathways trigger telomere dysfunction in cancer.

a | Telomere attrition induces telomere dysfunction and promotes gross chromosomal rearrangement due to breakage–fusion–bridge cycles (a non-reciprocal translocation is shown). Telomerase reactivation is a key event that stabilizes chromosome ends and supports the proliferation of tumours. b | Recurrent mutations in the TERT promoter are common in many cancers and seem to create a de novo binding site for the transcription factor GABP (GA-binding protein transcription factor). c | Deficiency in the shelterin subunit POT1 (protection of telomere 1) represent a novel mechanism that triggers telomere dysfunction in cancer. POT1 mutations induce telomere fragility and are associated with considerable telomere elongation. POT1 mutations also manifest in a mild chromosome fusion phenotype, which is predicted to induce chromosomal instability and augment tumour progression. d | POT1 mutations cluster primarily in its oligonucleotide-binding (OB) fold domains and are widespread across many tumour types.

It was first proposed by McClintock1 that dicentric chromosomes undergo repeated cycles of breakage–fusion–bridge leading to chromosomal rearrangements. Almost eight decades later, the fate of human dicentric chromosomes derived from telomere fusions162 was traced using live-cell imaging. Surprisingly, dicentric chromosomes form anaphase bridges that persist through mitosis and are processed by the cytoplasmic nuclease TREX1 (three prime repair exonuclease 1). Clones that survive this crisis stage display chromothripsis and kataegis, which are localized hypermutation events often found in cancer genomes. Interestingly, previous work suggested a crucial role for DNA ligase 3 in the survival of cells undergoing telomere dysfunction163. It is therefore possible that DNA ligase 3 is required for processing of TREX1-generated DNA breaks, leading to hypermutagenesis.

This paradigm of telomere dysfunction and cancer has been tested in vivo using the telomerase-knockout mouse. When combined with p53 mutations, later generations of telomerase-null mice display accelerated tumour formation and a shift in the tumour spectrum towards mostly carcinomas164,165, characterized by non-reciprocal translocations and chromosome fusions164. One caveat with the telomerase-knockout mouse model is that constitutive telomerase deficiency constrains tumour progression. In order to firmly establish the function of telomere dysfunction in malignancy and metastasis, an inducible telomerase allele was studied in the context of a PTEN mouse model of prostate cancer. Reactivation of telomerase in tumour cells that have already experienced telomere dysfunction was sufficient to suppress DNA damage signalling, and, importantly, resulted in the formation of highly metastatic tumours that invade the bone166.

In addition to these animal studies, evidence in support of a role for telomere dysfunction during tumorigenesis came from the analysis of telomeres in cells derived from cancer patients at different stages of the disease167–169. Specifically, telomere fusions, which were detected molecularly using a PCR-based method, were evident in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and breast cancers, and were found to be predictive of poor prognosis66,67.

The reactivation of human telomerase is crucial for malignant progression. Telomerase activity has been detected in ~90% of human cancers170, and its inhibition limits the survival of human cancer cells171. Mutations in the promoter region of TERT are among the most prevalent mutations in cancers. The first mutations identified in a genome-wide association study of melanoma patients are in close proximity to the TERT transcription start site and create a binding motif for the ternary complex factor (TCF) and E-twenty-six (ETS)-domain transcription factors172,173. Subsequent sequence analysis identified similar point mutations in the TERT promoter in a wide range of cancers172–182; in glioblastomas, the mutations facilitate the recruitment of the multimeric GA-binding protein (GABP) transcription factor to the TERT promoter region182 (FIG. 6b). In many cases, the mutations correlate with increased TERT transcription and enhanced telomerase activity174,180. The TERT promoter mutations were recently engineered into human embryonic stem cells (hES cells) using the CRISPR–Cas9 editing system. In pluripotent cells, which already express TERT, the mutations did not increase telomerase activity, but they prevented telomerase silencing upon differentiation of hES cells183. Whether such mutations can lead to telomerase reactivation in somatic cells remains to be addressed. It is worth noting that a significant number of telomerase-positive tumours do not carry mutations in the TERT promoter, suggesting that additional TERT-activating pathway(s) may exist and are yet to be determined.

A novel way in which cancer cells do business

The sequencing of cancer genomes highlighted a potentially novel mechanism capable of inducing telomere dysfunction and promoting genomic instability in tumours (FIG. 6c). Acquired mutations in POT1 were noted in CLL (chronic lymphocytic leukaemia)184,185, and shortly thereafter, mis-sense variants of POT1 were identified in familial melanoma186,187, gliomas188, mantle cell lym-phomas187, and T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma189 (FIG. 6d). Interestingly, analysis of the clonal evolution of several mutations in CLL patients suggested that POT1 mutations arise early in CLL development and are likely to contribute to disease progression190. Despite their prevalence among many different cancer types, the mechanism by which POT1 mutations induce telomere dysfunction and influence tumour progression is not fully understood. Limited functional analyses indicate that POT1 mutations lead to telomere elongation, increased telomere fragility and mild telomere fusion phenotype185,191. Chromosome end-to-end fusions can instigate breakage–fusion–bridge cycles, leading to increased genomic instability in POT1-mutated tumours. The observed telomere fragility suggests that replication defects triggered by POT1 alterations constitute a novel type of tumour-promoting mechanism. Future experiments are necessary to reveal how the identified cancer-associated POT1 mutations induce telomere fragility.

The identification of POT1 mutations raises the question of whether other shelterin subunits, especially ones that induce telomere fragility, are mutated in cancers. Nonsense mutations in TPP1 and RAP1 were recently detected in melanoma192. Although no TRF1 mutations have been detected so far, it is noteworthy that mice with reduced TRF1 levels have increased incidence of lymphoid tumours193, and deletion of TRF1 in p53-null keratinocytes leads to squamous cell carcinomas83. In the same way, mice carrying a mutation in RTEL1, which affects telomere replication, display accelerated tumorigenesis85.

But humans are not mice!

A recurrent concern in evaluating mouse models of human diseases is that humans, after all, are not mice. Telomere biology is not an exception and there are significant differences between human and mouse telomeres that need to be taken into consideration when evaluating mouse models of telomere dysfunction. Two key differences are the length of telomeres and the regulation of telomerase. Mice have significantly longer telomeres compared with humans, and they express telomerase in most cell types. As a result, telomere shortening is not a limiting factor in the lifespan of a mouse cell or in murine tumours. The composition of shelterin is also different in that mice have two POT1 orthologues, POT1A and POT1B. POT1A is more closely related to human POT1 in its ability to prevent DDR activation, whereas POT1B is mainly involved in preventing resection at chromosomes22. Additional differences in the composition of telomeric chromatin between mouse and human telomeres might exist. The use of CRISPR–Cas9-mediated gene editing is likely to highlight the function of individual telomere-associated proteins in human cells and may provide additional insights into the differences between mouse and human telomeres.

Conclusions

It is now clear that there is a great degree of specialization within the shelterin complex in suppressing different DDR pathways. However, we still do not have a full understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which the shelterin subunits silence the DDR. Furthermore, how fragile telomeres lead to genomic instability and tumour formation remains unknown and merits further investigation. Thus far, manipulating shelterin to trigger telomere uncapping has been successfully used to identify novel factors involved in DSB processing and repair. Deprotected telomeres continue to be used to improve our understanding of the DDR; for instance, telomeres may provide a powerful tool in which the role of histone modifications and chromatin remodelling factors in the DDR can be addressed. Sequencing of cancer genomes has provided a wealth of information on recurrent mutations in genes involved in telomere maintenance and protection. Continued investigation into how these mutations promote tumour progression and how cancerous cells evade the detrimental effect of telomere dysfunction will provide a greater understanding of the role of telomere biology in cancer progression and, hopefully, will guide the development of new and better therapies for cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to the colleagues whose work they could not cite owing to space constraints. They thank A. Penev, S. K. Deng, Lynda Groocock, F. Lottersberger and D. Conomos for comments on the manuscript. Research in the authors’ laboratories is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (DP2CA195767 and DK102562 to A.S., and AG038677 to E.L.D.) and the American Cancer Society (RSG-14-186) to E.L.D. A.S. is a Pew-Stewart Scholar, a Damon Runyon-Rachleff grant recipient and a fellow of the David and Lucille Packard foundation.

Glossary

- DNA damage response (DDR)

A collection of pathways that sense, signal and repair DNA lesions.

- Dicentric chromosomes

Aberrant chromosomes with two centromeres, resulting from the fusion of two chromosomes.

- Breakage–fusion–bridge

A mechanism producing chromosomal instability, triggered by the fusion of deprotected telomeres, which leads to repeating cycles of chromosome breakage and fusion.

- Fragile telomeres

Breaks or gaps at telomeres of metaphase chromosomes, caused by replication stress.

- Fragile sites

Genomic regions that appear as gaps or breaks on metaphase chromosomes when DNA replication is partially inhibited.

- ALT-associated PML bodies (APBs)

Promyelocytic leukaemia (PML) bodies are dynamic protein aggregates within the nuclei of some cells that contain the PML protein. Alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT)-associated PML bodies are found exclusively in cancer cells, which rely on the ALT pathway to maintain telomeres.

- Quantitative telomeric chromatin isolation protocol (QTIP)

A telomere-protein purification method used to quantify changes in the content of telomeric chromatin.

- Proteomics of isolated chromatin segments (PICh)

A method to identify proteins associated with specific genomic loci that are rich in repetitive DNA.

- Telomere biology disorder (TBD)

One of a set of pathologies that are defined by the presence of short telomeres.

- Chromothripsis

A mutational phenomenon that involves catastrophic shattering and rebuilding of chromosomes, leading to multiple clustered chromosomal rearrangements.

- Kataegis

Clustered point mutations that localize to particular regions of certain cancer genomes.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.McClintock B. The stability of broken ends of chromosomes in Zea mays. Genetics. 1941;26:234–282. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meier R, Muller R. A new arrangement for the registration of diaphragm movements. J Physiol. 1938;94:227–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1938.sp003675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greider CW. Telomerase and telomere-length regulation: lessons from small eukaryotes to mammals. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:719–723. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makarov VL, Hirose Y, Langmore JP. Long G tails at both ends of human chromosomes suggest a C strand degradation mechanism for telomere shortening. Cell. 1997;88:657–666. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McElligott R, Wellinger RJ. The terminal DNA structure of mammalian chromosomes. EMBO J. 1997;16:3705–3714. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffith JD, et al. Mammalian telomeres end in a large duplex loop. Cell. 1999;97:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80760-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doksani Y, Wu JY, de Lange T, Zhuang X. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of telomeres reveals TRF2-dependent T-loop formation. Cell. 2013;155:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azzalin CM, Reichenbach P, Khoriauli L, Giulotto E, Lingner J. Telomeric repeat containing RNA and RNA surveillance factors at mammalian chromosome ends. Science. 2007;318:798–801. doi: 10.1126/science.1147182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzalin CM, Lingner J. Telomere functions grounding on TERRA firma. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chong L, et al. A human telomeric protein. Science. 1995;270:1663–1667. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broccoli D, Smogorzewska A, Chong L, de Lange T. Human telomeres contain two distinct Myb-related proteins, TRF1 and TRF2. Nat Genet. 1997;17:231–235. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilaud T, et al. Telomeric localization of TRF2, a novel human telobox protein. Nat Genet. 1997;17:236–239. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ye JZ, de Lange T. TIN2 is a tankyrase 1 PARP modulator in the TRF1 telomere length control complex. Nat Genet. 2004;36:618–623. doi: 10.1038/ng1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye JZ, et al. POT1-interacting protein PIP1: a telomere length regulator that recruits POT1 to the TIN2/TRF1 complex. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1649–1654. doi: 10.1101/gad.1215404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Houghtaling BR, Cuttonaro L, Chang W, Smith S. A dynamic molecular link between the telomere length regulator TRF1 and the chromosome end protector TRF2. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1621–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SH, Kaminker P, Campisi J. TIN2, a new regulator of telomere length in human cells. Nat Genet. 1999;23:405–412. doi: 10.1038/70508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu D, et al. PTOP interacts with POT1 and regulates its localization to telomeres. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ncb1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumann P, Cech TR. Pot1, the putative telomere end-binding protein in fission yeast and humans. Science. 2001;292:1171–1175. doi: 10.1126/science.1060036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loayza D, De Lange T. POT1 as a terminal transducer of TRF1 telomere length control. Nature. 2003;423:1013–1018. doi: 10.1038/nature01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu L, et al. Pot1 deficiency initiates DNA damage checkpoint activation and aberrant homologous recombination at telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hockemeyer D, Daniels JP, Takai H, de Lange T. Recent expansion of the telomeric complex in rodents: two distinct POT1 proteins protect mouse telomeres. Cell. 2006;126:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Oestreich S, de Lange T. Identification of human Rap1: implications for telomere evolution. Cell. 2000;101:471–483. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80858-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celli GB, de Lange T. DNA processing is not required for ATM-mediated telomere damage response after TRF2 deletion. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:712–718. doi: 10.1038/ncb1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sfeir A, Kabir S, van Overbeek M, Celli GB, de Lange T. Loss of Rap1 induces telomere recombination in the absence of NHEJ or a DNA damage signal. Science. 2010;327:1657–1661. doi: 10.1126/science.1185100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye JZ, et al. TIN2 binds TRF1 and TRF2 simultaneously and stabilizes the TRF2 complex on telomeres. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47264–47271. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dejardin J, Kingston RE. Purification of proteins associated with specific genomic loci. Cell. 2009;136:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grolimund L, et al. A quantitative telomeric chromatin isolation protocol identifies different telomeric states. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2848. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartocci C, et al. Isolation of chromatin from dysfunctional telomeres reveals an important role for Ring1b in NHEJ-mediated chromosome fusions. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1320–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nittis T, et al. Revealing novel telomere proteins using in vivo cross-linking, tandem affinity purification, and label-free quantitative LC-FTICR-MS. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1144–1156. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900490-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyake Y, et al. RPA-like mammalian Ctc1–Stn1–Ten1 complex binds to single-stranded DNA and protects telomeres independently of the Pot1 pathway. Mol Cell. 2009;36:193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surovtseva YV, et al. Conserved telomere maintenance component 1 interacts with STN1 and maintains chromosome ends in higher eukaryotes. Mol Cell. 2009;36:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shibuya H, et al. MAJIN links telomeric DNA to the nuclear membrane by exchanging telomere cap. Cell. 2015;163:1252–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shibuya H, Ishiguro K, Watanabe Y. The TRF1-binding protein TERB1 promotes chromosome movement and telomere rigidity in meiosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:145–156. doi: 10.1038/ncb2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiloh Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:155–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karlseder J, et al. The telomeric protein TRF2 binds the ATM kinase and can inhibit the ATM-dependent DNA damage response. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E240. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denchi EL, de Lange T. Protection of telomeres through independent control of ATM and ATR by TRF2 and POT1. Nature. 2007;448:1068–1071. doi: 10.1038/nature06065. In this publication, the authors demonstrate that ATM and ATR signalling are repressed by TRF2 and POT1, respectively, and that efficient end joining of deprotected telomeres is dependent on DNA damage signalling. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takai H, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1549–1556. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amiard S, et al. A topological mechanism for TRF2-enhanced strand invasion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:147–154. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamoto K, et al. A two-step mechanism for TRF2-mediated chromosome-end protection. Nature. 2013;494:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature11873. This publication highlights a mechanism by which TRF2 inhibits ATM signalling and identifies the iDDR domain of TRF2 as important for RNF168 inhibition. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benarroch-Popivker D, et al. TRF2-mediated control of telomere DNA topology as a mechanism for chromosome-end protection. Mol Cell. 2016;61:274–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Steensel B, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. TRF2 protects human telomeres from end-to-end fusions. Cell. 1998;92:401–413. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80932-0. This report demonstrates that deprotection of telomeres by inhibiting the function of human TRF2 leads to chromosome fusions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fumagalli M, et al. Telomeric DNA damage is irreparable and causes persistent DNA-damage-response activation. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:355–365. doi: 10.1038/ncb2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu D, O’Connor MS, Qin J, Songyang Z. Telosome, a mammalian telomere-associated complex formed by multiple telomeric proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51338–51342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takai KK, Hooper S, Blackwood S, Gandhi R, de Lange T. In vivo stoichiometry of shelterin components. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1457–1467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarthy J, Bae NS, Scrafford J, Baumann P. Human RAP1 inhibits non-homologous end joining at telomeres. EMBO J. 2009;28:3390–3399. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kabir S, Hockemeyer D, de Lange T. TALEN gene knockouts reveal no requirement for the conserved human shelterin protein Rap1 in telomere protection and length regulation. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martinez P, et al. Mammalian Rap1 controls telomere function and gene expression through binding to telomeric and extratelomeric sites. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:768–780. doi: 10.1038/ncb2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu HL, Gilley D, Blackburn EH, Chen DJ. Ku is associated with the telomere in mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12454–12458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang Y, Ghosh G, Hendrickson EA. Ku86 represses lethal telomere deletion events in human somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12430–12435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903362106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gu Y, et al. Growth retardation and leaky SCID phenotype of Ku70-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:653–665. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80386-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samper E, Goytisolo FA, Slijepcevic P, van Buul PP, Blasco MA. Mammalian Ku86 protein prevents telomeric fusions independently of the length of TTAGGG repeats and the G-strand overhang. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:244–252. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ribes-Zamora A, Indiviglio SM, Mihalek I, Williams CL, Bertuch AA. TRF2 interaction with Ku heterotetramerization interface gives insight into c-NHEJ prevention at human telomeres. Cell Rep. 2013;5:194–206. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayashi MT, Cesare AJ, Fitzpatrick JA, Lazzerini-Denchi E, Karlseder J. A telomere-dependent DNA damage checkpoint induced by prolonged mitotic arrest. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:387–394. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Orthwein A, et al. Mitosis inhibits DNA double-strand break repair to guard against telomere fusions. Science. 2014;344:189–193. doi: 10.1126/science.1248024. This publication identifies the molecular mechanism that allows mammalian cells to inhibit DSB repair during mitosis. The authors show that restoring mitotic DSB repair results in severe genomic instability owing to the accumulation of telomere fusions. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayashi MT, Cesare AJ, Rivera T, Karlseder J. Cell death during crisis is mediated by mitotic telomere deprotection. Nature. 2015;522:492–496. doi: 10.1038/nature14513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo X, et al. Dysfunctional telomeres activate an ATM-ATR-dependent DNA damage response to suppress tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2007;26:4709–4719. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kibe T, Osawa GA, Keegan CE, de Lange T. Telomere protection by TPP1 is mediated by POT1a and POT1b. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1059–1066. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01498-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takai KK, Kibe T, Donigian JR, Frescas D, de Lange T. Telomere protection by TPP1/POT1 requires tethering to TIN2. Mol Cell. 2011;44:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gong Y, de Lange TA. Shld1-controlled POT1a provides support for repression of ATR signaling at telomeres through RPA exclusion. Mol Cell. 2010;40:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zou L, Elledge SJ. Sensing DNA damage through ATRIP recognition of RPA-ssDNA complexes. Science. 2003;300:1542–1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1083430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flynn RL, et al. TERRA and hnRNPA1 orchestrate an RPA-to-POT1 switch on telomeric single-stranded DNA. Nature. 2011;471:532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature09772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sfeir A, et al. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell. 2009;138:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.021. This publication identifies telomere replication defects as the major consequence of TRF1 loss in mouse cells and defines telomere fragility as a hallmark of replication stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmermann M, Kibe T, Kabir S, de Lange T. TRF1 negotiates TTAGGG repeat-associated replication problems by recruiting the BLM helicase and the TPP1/POT1 repressor of ATR signaling. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2477–2491. doi: 10.1101/gad.251611.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong KK, et al. Diminished lifespan and acute stress-induced death in DNA-PKcs-deficient mice with limiting telomeres. Oncogene. 2007;26:2815–2821. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin TT, et al. Telomere dysfunction and fusion during the progression of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: evidence for a telomere crisis. Blood. 2010;116:1899–1907. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-272104. In this study, the authors carry out single-molecule telomere analysis in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and report the incidence of telomere erosion and, subsequently, telomere fusions in advanced stages of the disease. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Simpson K, et al. Telomere fusion threshold identifies a poor prognostic subset of breast cancer patients. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:1186–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Letsolo BT, Rowson J, Baird DM. Fusion of short telomeres in human cells is characterized by extensive deletion and microhomology, and can result in complex rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1841–1852. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sfeir A, de Lange T. Removal of shelterin reveals the telomere end-protection problem. Science. 2012;336:593–597. doi: 10.1126/science.1218498. This publication delineates the process of end protection by removing all six subunits of the shelterin complex and identifying the various DNA damage signalling and repair pathways activated at deprotected chromosome ends. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rai R, et al. The function of classical and alternative non-homologous end-joining pathways in the fusion of dysfunctional telomeres. EMBO J. 2010;29:2598–2610. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Badie S, et al. BRCA1 and CtIP promote alternative non-homologous end-joining at uncapped telomeres. EMBO J. 2015;34:410–424. doi: 10.15252/embj.201488947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheng Q, et al. Ku counteracts mobilization of PARP1 and MRN in chromatin damaged with DNA double-strand breaks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9605–9619. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang M, et al. PARP-1 and Ku compete for repair of DNA double strand breaks by distinct NHEJ pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6170–6182. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clerici M, Mantiero D, Guerini I, Lucchini G, Longhese MP. The Yku70-Yku80 complex contributes to regulate double-strand break processing and checkpoint activation during the cell cycle. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:810–818. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mimitou EP, Symington LS. Ku prevents Exo1 and Sgs1-dependent resection of DNA ends in the absence of a functional MRX complex or Sae2. EMBO J. 2010;29:3358–3369. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Truong LN, et al. Microhomology-mediated end joining and homologous recombination share the initial end resection step to repair DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7720–7725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213431110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3′ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell. 2012;150:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu P, van Overbeek M, Rooney S, de Lange T. Apollo contributes to G overhang maintenance and protects leading-end telomeres. Mol Cell. 2010;39:606–617. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lam YC, et al. SNMIB/Apollo protects leading-strand telomeres against NHEJ-mediated repair. EMBO J. 2010;29:2230–2241. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chai W, Shay JW, Wright WE. Human telomeres maintain their overhang length at senescence. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2158–2168. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2158-2168.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lottersberger F, Bothmer A, Robbiani DF, Nussenzweig MC, de Lange T. Role of 53BP1 oligomerization in regulating double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:2146–2151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222617110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Parkinson GN, Lee MP, Neidle S. Crystal structure of parallel quadruplexes from human telomeric DNA. Nature. 2002;417:876–880. doi: 10.1038/nature755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martinez P, et al. Increased telomere fragility and fusions resulting from TRF1 deficiency lead to degenerative pathologies and increased cancer in mice. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2060–2075. doi: 10.1101/gad.543509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miller KM, Rog O, Cooper JP. Semi-conservative DNA replication through telomeres requires Taz1. Nature. 2006;440:824–828. doi: 10.1038/nature04638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vannier JB, et al. RTEL1 is a replisome-associated helicase that promotes telomere and genome-wide replication. Science. 2013;342:239–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1241779. This publication describes an interaction between RTEL1 and PCNA. Blocking this interaction affects genome-wide replication, induces telomere fragility and accelerates the onset of tumorigenesis in p53-deficient mice. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Drosopoulos WC, Kosiyatrakul ST, Schildkraut CL. BLM helicase facilitates telomere replication during leading strand synthesis of telomeres. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:191–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201410061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crabbe L, Verdun RE, Haggblom CI, Karlseder J. Defective telomere lagging strand synthesis in cells lacking WRN helicase activity. Science. 2004;306:1951–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.1103619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnoult N, Saintome C, Ourliac-Garnier I, Riou JF, Londono-Vallejo A. Human POT1 is required for efficient telomere C-rich strand replication in the absence of WRN. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2915–2924. doi: 10.1101/gad.544009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stewart JA, et al. Human CST promotes telomere duplex replication and general replication restart after fork stalling. EMBO J. 2012;31:3537–3549. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kasbek C, Wang F, Price CM. Human TEN1 maintains telomere integrity and functions in genome-wide replication restart. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:30139–30150. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.493478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ye J, et al. TRF2 and Apollo cooperate with topoisomerase 2α to protect human telomeres from replicative damage. Cell. 2010;142:230–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pierce AJ, Hu P, Han M, Ellis N, Jasin M. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3237–3242. doi: 10.1101/gad.946401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Celli GB, Denchi EL, de Lange T. Ku70 stimulates fusion of dysfunctional telomeres yet protects chromosome ends from homologous recombination. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ncb1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]