Abstract

AIM

To identify the factors influencing cecal insertion time (CIT) and to evaluate the effect of obesity indices on CIT.

METHODS

We retrospectively reviewed the data for participants who received both colonoscopy and abdominal computed tomography (CT) from February 2008 to May 2008 as part of a comprehensive health screening program. Age, gender, obesity indices [body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip circumference ratio (WHR), waist circumference (WC), visceral adipose tissue (VAT) volume and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) volume on abdominal CT], history of prior abdominal surgery, constipation, experience of the colonoscopist, quality of bowel preparation, diverticulosis and time required to reach the cecum were analyzed. CIT was categorized as longer than 10 min (prolonged CIT) and shorter than or equal to 10 min, and then the factors that required a CIT longer than 10 min were examined.

RESULTS

A total of 1678 participants were enrolled. The mean age was 50.42 ± 9.931 years and 60.3% were men. The mean BMI, WHR, WC, VAT volume and SAT volume were 23.92 ± 2.964 kg/m2, 0.90 ± 0.076, 86.95 ± 8.030 cm, 905.29 ± 475.220 cm3 and 1707.72 ± 576.550 cm3, respectively. The number of patients who underwent abdominal surgery was 268 (16.0%). Colonoscopy was performed by an attending physician alone in 61.9% of cases and with the involvement of a fellow in 38.1% of cases. The median CIT was 7 min (range 2-56 min, IQR 5-10 min), and mean CIT was 8.58 ± 5.291 min. Being female, BMI, VAT volume and involvement of fellow were significantly associated with a prolonged CIT in univariable analysis. In multivariable analysis, being female (OR = 1.29, P = 0.047), lower BMI (< 23 kg/m2) (OR = 1.62, P = 0.004) or higher BMI (≥ 25 kg/m2) (OR = 1.80, P < 0.001), low VAT volume (< 500 cm3) (OR = 1.50, P = 0.013) and fellow involvement (OR = 1.73, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of prolonged CIT. In subgroup analyses for gender, lower BMI or higher BMI and fellow involvement were predictors for prolonged CIT in both genders. However, low VAT volume was associated with prolonged CIT in only women (OR = 1.54, P = 0.034).

CONCLUSION

Being female, having a lower or higher BMI than the normal range, a low VAT volume, and fellow involvement were predictors of a longer CIT.

Keywords: Visceral obesity, Difficult colonoscopy, Cecal insertion time, Body mass index, Female

Core tip: There are well known predictive factors of longer cecal intubation time (CIT). Old age, female, poor quality of bowel preparation, history of prior abdominal surgery, trainee, diverticulosis and constipation are associated with longer CIT. A low visceral adipose tissue (VAT) volume, female, having a lower or higher body mass index, and fellow involvement were predictors of a longer CIT based on the present study. Especially, low VAT volume was associated with prolonged CIT in only women.

INTRODUCTION

Colonoscopy is widely used for the diagnosis and treatment of colon disorders and is one of the recommended options for colorectal cancer screening[1]. Although the success rate of complete colonoscopy is reported to be as high as 95% to 99%, cecal insertion time (CIT) varies greatly in different cases and is considered a surrogate measure for difficult colonoscopy[2-4]. The mean CIT by experienced colonoscopists has been reported to be between 10 and 20 min[5]. The authors of another study insisted that experienced endoscopists should intubate the cecum in > 90% of cases in < 15 min[6]. Although there is no standard definition of a difficult colonoscopy, procedure times with more than 10 min for insertion or more than two attempts to reach the cecum, or finally failed insertion are often considered difficult[4,7,8].

Identifying the factors predicting longer CIT is important to colonoscopists, especially for recognition of patients who may need a longer scheduled interval, sedation and vital monitoring requirements, and better colonoscopic expertise[9]. Various factors have been implicated in influencing CIT. These factors included age, gender, quality of bowel preparation, history of prior abdominal surgery, experience of the colonoscopist, diverticulosis and constipation[4,10-14]. In addition, research on the relationship between CIT and obesity indices, such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), visceral adipose tissue (VAT) area and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) area, has been reported[9,13,15-17]. However, the results of previous studies are conflicting. A few studies on the association between VAT and CIT were reported based on the visceral fat amount using abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan[4,13]. In these previous studies, visceral fat was calculated on the basis of only one slice of abdominal CT at the umbilical level.

The aims of this study were to identify the factors influencing CIT and to evaluate the effect of obesity indices on CIT. For reflecting the effects of visceral fat on CIT more accurately, visceral fat was calculated as volume in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

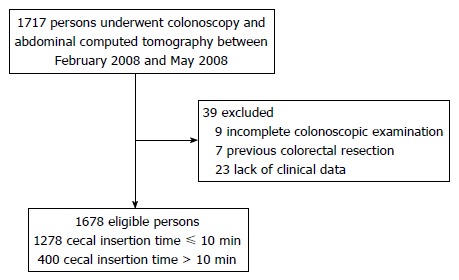

We selected participants who received colonoscopy, abdominal CT, and questionnaire assessment from February 2008 to May 2008 among persons enrolled in our previous study on the association between abdominal VAT volume and colorectal adenoma[18]. Participants who previously had undergone surgery for colorectal disease including malignancy, or had incomplete examination, inflammatory bowel disease or lack of clinical data were excluded. Surgical history and constipation were investigated through a questionnaire. Between February 2008 to May 2008, 1717 participants received colonoscopy and abdominal CT in a health screening program. Of the 1717 persons, 1678 participants met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion of study participants.

Data were collected in a prospectively maintained database that was further supplemented by a retrospective chart review. This study was approved by the institutional review board (NCC2016-0217).

Anthropometric measurements

BMI was calculated as body weight by height squared (kg/m2) and then divided into three categories as in previous studies: BMI < 23 kg/m2, 23-24.9 kg/m2, and ≥ 25 kg/m2[9,13]. WC was measured at the midpoint between the lower -costal margin and the upper pole of the iliac crest. Patients were classified into two categories by WC according to WHO criteria: normal WC (≤ 102 cm for men, ≤ 88 cm for women) and high WC (> 102 cm for men, > 88 cm for women). Hip circumference (HC) was measured using the greatest circumference between the iliac crest and thighs. The waist-to-hip circumference ratio (WHR) was calculated as WC divided by HC. Two levels of WHR were classified as follows according to WHO criteria: normal WHR (≤ 0.9 for men, ≤ 0.8 for women) and high WHR (> 0.9 for men, > 0.8 for women).

Measurement of abdominal adipose tissue volume

Adipose tissue volume was calculated using 20 slices covering 100 mm from 50 mm above to 50 mm below the umbilicus as previously mentioned[18]. VAT volume was measured as intra-abdominal fat bound by parietal peritoneum or transversalis fascia, excluding the vertebral column and paraspinal muscles. The SAT volume was calculated by subtracting the VAT volume from the total adipose tissue volume. The participants were classified into 3 groups according to VAT volume (< 500 cm3, 500-1499 cm3, and ≥ 1500 cm3) and according to SAT volume (< 1000 cm3, 1000-1999 cm3, and ≥ 2000 cm3) based on a previous study[18].

Colonoscopy

All colonoscopies were performed with an Olympus CF-Q260AL video colonoscope (Olympus Optical, Co, Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) after preparatory bowel cleansing with a 4-L of aqueous Fleet Phospho-soda (Fleet Company, Inc, Lynchburg, VA, United States). All colonoscopy procedures were performed by attending physicians specializing in endoscopy and fellows under the direction of attending physicians. Patients who chose to have sedation were given intravenous midazolam before colonoscopy initiation. The dosages were adjusted according to the patient’s age and weight. The quality of bowel preparation was graded by the colonoscopist according to the Aronchick scale[19] and reclassified into two classes as excellent to fair and poor to inadequate for statistical analysis. The presence of diverticular disease was recorded by the colonoscopist. CIT was categorized as longer than 10 min (prolonged CIT) and shorter than or equal to 10 min[4,7,8].

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of study participants and colonoscopic data were reported as the mean ± SD or number (percentage). Pearson’s χ2 testing was performed for the statistical comparison of proportions among groups in univariate analysis. Only factors with P values < 0.05 in univariable analysis were subsequently estimated with odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CI using logistic regression multivariable analysis. We performed the further subgroup analysis according to the gender. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of study participants and colonoscopic data are shown in Table 1. The mean age of 1678 participants was 50.42 ± 9.93 years and 60.3% were male. The mean BMI, WHR, WC, VAT volume, and SAT volume were 23.92 ± 2.96 kg/m2, 0.90 ± 0.08, 86.95 ± 8.03 cm, 905.29 ± 475.22 cm3 and 1707.72 ± 576.55 cm3, respectively. The number of participants who received abdominal surgery was 268 (16.0%). Colonoscopy was performed by an attending physician alone in 61.9% of cases and with the involvement of a fellow in 38.1% of cases. The median CIT was 7 min (range 2-56 min, IQR 5-10 min), and mean CIT was 8.58 ± 5.29 min. Four hundred (23.8%) of participants required longer than 10 min.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants n (%)

| Baseline characteristics (n = 1678) | |

| Age (yr) (mean ± SD) | 50.42 ± 9.93 |

| < 65 | 1518 (90.5) |

| ≥ 65 | 160 (9.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male/female | 1012 (60.3)/666 (39.7) |

| Obesity indices (mean ± SD) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.92 ± 2.96 |

| WHR (n =1674) | 0.90 ± 0.08 |

| WC (cm) (n =1676) | 86.95 ± 8.03 |

| VAT volume (cm3) | 905.29 ± 475.22 |

| SAT volume (cm3) | 1707.72 ± 576.55 |

| History of abdominal surgery | |

| Gynecological surgery | 231 (13.8) |

| Gastrectomy | 163 (9.7) |

| Other abdominal surgery | 5 (0.3) |

| Constipation | |

| Yes/no | 182 (10.8)/1496 (89.2) |

| Experience | |

| Attending physicians/Fellow | 1039 (61.9)/639 (38.1) |

| Bowel preparation | |

| Excellent to fair/Poor to inadequate | 1209 (72.1)/469 (27.9) |

| Diverticulosis on colonoscopy | |

| Yes/no | 95 (5.7)/1583 (94.3) |

| CIT (min) | |

| Median CIT (range) | 7 (2-56) (IQR, 5-10) |

| Mean CIT (SD)1 | 8.58 ± 5.29 |

| ≤ 10 min | 1278 (76.2) |

| > 10 min | 400 (23.8) |

One hundred thirty one patients were undergone multiple surgeries and duplicated with other type operation. BMI: Body mass index; WHR: Waist-to-hip circumference ratio; WC: Waist circumference; VAT: Visceral adipose tissue; SAT: Subcutaneous adipose tissue; CIT: Cecal insertion time.

Predictors of prolonged CIT

The univariable analysis for predictors of prolonged CIT is shown in Table 2. Gender, BMI, VAT volume and involvement of a fellow were significantly associated with a prolonged CIT. Among these variables, being female (OR = 1.29, 95%CI: 1.00-1.67, P = 0.047), BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.62, 95%CI: 1.16-2.25, P = 0.004) or greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.80, 95%CI: 1.31-2.49, P < 0.001), VAT volume smaller than 500 cm3 (OR = 1.50; 95%CI: 1.09-2.07, P = 0.013) and fellow involvement (OR = 1.73; 95%CI: 1.38-2.19, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis (Table 2). When BMI and VAT volume were considered separately by multivariable analysis in total cohort (Supplement Table 2), being female, BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.84, 95%CI: 1.35-2.50, P < 0.001) or greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.34-2.50, P < 0.001), VAT volume smaller than 500 cm3 (OR = 1.57, 95%CI: 1.18-2.09, P = 0.002) or greater than or equal to 1500 cm3 (OR = 1.45, 95%CI: 1.00-2.09, P = 0.047) and fellow involvement were independently associated with prolonged CIT.

Table 2.

Cecal insertion time according to study variables, with odd ratios estimated by multivariable logistic regression analysis n (%)

|

Cecal insertion time (min) |

P value | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | P value | ||

| ≤ 10 (n = 1278) | > 10 (n = 400) | OR (95%CI) | |||

| Age (yr) | 0.125 | ||||

| < 65 | 1164 (76.7) | 354 (23.3) | |||

| ≥ 65 | 114 (71.3) | 46 (28.7) | |||

| Gender | 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 800 (79.1) | 212 (20.9) | Ref | 0.047 | |

| Female | 478 (71.8) | 188 (28.2) | 1.29 (1.00-1.67) | ||

| Obesity indices | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 23 | 457 (72.2) | 176 (27.8)a | 1.62 (1.16-2.25) | 0.004 | |

| 23-24.9 | 388 (83.6) | 76 (16.4)b | Ref | ||

| ≥ 25 | 433 (74.5) | 148 (25.5) | 1.80 (1.31-2.49) | < 0.001 | |

| WHR (n = 1674) | 0.060 | ||||

| Normal (≤ 0.9 for men, ≤ 0.8 for women) | 257 (72.4) | 98 (27.6) | |||

| High | 1018 (77.2) | 301 (22.8) | |||

| WC (cm) (n = 1676) | 0.316 | ||||

| Normal (≤ 102 cm for men, ≤ 88 cm for women) | 1098 (76.6) | 335 (23.4) | |||

| High | 179 (73.7) | 64 (26.3) | |||

| VAT volume (cm3) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 500 | 237 (68.3) | 110 (31.7)c | 1.50 (1.09-2.07) | 0.013 | |

| 500-1499 | 906 (78.9) | 242 (21.1) | Ref | ||

| ≥ 1500 | 135 (73.8) | 48 (26.2) | 1.27 (0.86-1.88) | 0.223 | |

| SAT volume (cm3) | 0.848 | ||||

| < 1000 | 107 (78.1) | 30 (21.9) | |||

| 1000-1999 | 831 (75.9) | 264 (24.1) | |||

| ≥ 2000 | 340 (76.2) | 106 (23.8) | |||

| History of abdominal surgery | 0.626 | ||||

| No | 1077 (76.4) | 333 (23.6) | |||

| Yes | 201 (75.0) | 67 (25.0) | |||

| Constipation | 0.112 | ||||

| No | 1148 (76.7) | 348 (23.3) | |||

| Yes | 130 (71.4) | 52 (28.6) | |||

| Experience | < 0.001 | ||||

| Attending physicians | 833 (80.2) | 206 (19.8) | Ref | ||

| Fellow | 445 (69.6) | 194 (30.4) | 1.73 (1.38-2.19) | < 0.001 | |

| Bowel preparation | 0.919 | ||||

| Excellent to fair | 920 (76.1) | 289 (23.9) | |||

| Poor to inadequate | 358 (76.3) | 111 (23.7) | |||

| Diverticulosis | 0.099 | ||||

| No | 1199 (75.7) | 384 (24.3) | |||

| Yes | 79 (83.2) | 16 (16.8) | |||

P < 0.001 vs BMI 23-24.9 kg/m2,

P < 0.001 vs BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2,

P < 0.001 vs VAT volume 500-1499 cm3. BMI: Body mass index; WHR: Waist-to-hip circumference ratio; WC: Waist circumference; VAT: Visceral adipose tissue; SAT: Subcutaneous adipose tissue.

We performed a subgroup analysis by gender. In the subgroup analysis of men (n = 1012), BMI and fellow involvement were associated with a prolonged CIT in univariable analysis (Table 3). Among these variables, BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.69; 95%CI: 1.10-2.60, P = 0.017) or greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.88; 95%CI: 1.28-2.75, P = 0.001), and fellow involvement (OR = 1.92, 95%CI: 1.41-2.63, P < 0.001) were significant predictors of prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis (Table 4). In the subgroup analysis of women (n = 666), BMI, VAT volume and fellow involvement were associated with a prolonged CIT in univariable analysis (Table 3). Among these variables, BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.02-2.69, P = 0.041) or greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.02-3.13, P = 0.042), VAT volume smaller than 500 cm3 (OR = 1.54, 95%CI: 1.03-2.31, P = 0.034) and fellow involvement (OR = 1.53, 95%CI: 1.08-2.16, P = 0.016) were significant predictors of prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis (Table 4). When BMI and VAT volume were considered separately by multivariable analysis for gender, in men, BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.69, 95%CI: 1.10-2.60, P = 0.017) or greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.88, 95%CI: 1.28-2.75, P = 0.001) and fellow involvement were independently associated with prolonged CIT. VAT volume, however, was not associated with prolonged CIT. In women, BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.96, 95%CI: 1.25-3.10, P = 0.004), VAT volume smaller than 500 cm3 (OR = 1.66, 95%CI: 1.17-2.35, P = 0.005) and fellow involvement were independently associated with prolonged CIT. BMI greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.71, 95%CI: 0.99-2.96, P = 0.053) was marginally associated with prolonged CIT.

Table 3.

Cecal insertion time according to study variables, by gender, with P values estimated by univariable analysis n (%)

|

Male (n = 1012) |

Female (n = 666) |

|||||

|

Cecal insertion time (min) |

P value |

Cecal insertion time (min) |

P value | |||

| ≤ 10 (n = 800) | > 10 (n = 212) | ≤ 10 (n = 478) | > 10 (n = 188) | |||

| Age (yr) | 0.089 | 0.619 | ||||

| < 65 | 726 (90.8) | 184 (86.8) | 438 (91.6) | 170 (90.4) | ||

| ≥ 65 | 74 (9.3) | 28 (13.2) | 40 (8.4) | 18 (9.6) | ||

| Obesity indices | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.007 | 0.013 | ||||

| < 23 | 202 (25.3) | 58 (27.4) | 255 (53.3) | 118 (62.8)b | ||

| 23-24.9 | 261 (32.6) | 46 (21.7)a | 127 (26.6) | 30 (16.0) | ||

| ≥ 25 | 337 (42.1) | 108 (50.9) | 96 (20.1) | 40 (21.3) | ||

| WHR | 0.414 | 0.332 | ||||

| Normal | 118 (14.8) | 36 (17.1) | 139 (29.1) | 62 (33.0) | ||

| High | 680 (85.2) | 175 (82.9) | 338 (70.9) | 126 (67.0) | ||

| WC (cm) | 0.396 | 0.508 | ||||

| Normal | 768 (96.1) | 201 (94.8) | 330 (69.0) | 134 (71.7) | ||

| High | 31 (3.9) | 11 (5.2) | 148 (31.0) | 53 (28.3) | ||

| VAT volume (cm3) | 0.123 | 0.020 | ||||

| < 500 | 73 (9.1) | 24 (11.3) | 164 (34.3) | 86 (45.7)c | ||

| 500-1499 | 606 (75.8) | 146 (68.9) | 300 (62.8) | 96 (51.1) | ||

| ≥ 1500 | 121 (15.1) | 42 (19.8) | 14 (2.9) | 6 (3.2) | ||

| SAT volume (cm3) | 0.511 | 0.082 | ||||

| < 1000 | 90 (11.3) | 23 (10.8) | 17 (3.6) | 7 (3.7) | ||

| 1000-1999 | 575 (71.9) | 146 (68.9) | 256 (53.6) | 118 (62.8) | ||

| ≥ 2000 | 135 (16.9) | 43 (20.3) | 205 (42.9) | 63 (33.5) | ||

| History of abdominal surgery | 0.087 | 0.213 | ||||

| No | 687 (85.9) | 172 (81.1) | 390 (81.6) | 161 (85.6) | ||

| Yes | 113 (14.1) | 40 (18.9) | 88 (18.4) | 27 (14.4) | ||

| Constipation | 0.480 | 0.350 | ||||

| No | 740 (92.5) | 193 (91.0) | 408 (85.4) | 155 (82.4) | ||

| Yes | 60 (7.5) | 19 (9.0) | 70 (14.6) | 33 (17.6) | ||

| Experience | < 0.001 | 0.015 | ||||

| Attending physicians | 552 (69.0) | 115 (54.2) | 281 (58.8) | 91 (48.4) | ||

| Fellow | 248 (31.0) | 97 (45.8) | 197 (41.2) | 97 (51.6) | ||

| Bowel preparation | 0.561 | 0.462 | ||||

| Excellent to fair | 561 (70.1) | 153 (72.2) | 359 (75.1) | 136 (72.3) | ||

| Poor to inadequate | 239 (29.9) | 59 (27.8) | 119 (24.9) | 52 (27.7) | ||

| Diverticulosis | 0.135 | 0.966 | ||||

| No | 734 (91.8) | 201 (94.8) | 465 (97.3) | 183 (97.3) | ||

| Yes | 66 (8.3) | 11 (5.2) | 13 (2.7) | 5 (2.7) | ||

WHR: male n = 1009, female n = 665; WC: male n = 1011, female n = 665.

P = 0.004 vs BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2,

P = 0.009 vs BMI 23-24.9 kg/m2,

P = 0.015 vs VAT volume 500-1499 cm3. BMI: Body mass index; WHR: Waist-to-hip circumference ratio; WC: Waist circumference; VAT: Visceral adipose tissue; SAT: Subcutaneous adipose tissue.

Table 4.

Predictive parameters of prolonged cecal insertion time according to gender by multivariable logistic regression analysis when body mass index and visceral adipose tissue volume were considered simultaneously or separately

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Male | BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| < 23 | 1.58 | 1.00-2.50 | 0.049 | 1.69 | 1.10-2.60 | 0.017 | ||||

| 23-24.9 | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| ≥ 25 | 1.82 | 1.22-2.71 | 0.003 | 1.88 | 1.28-2.75 | 0.001 | ||||

| VAT volume (cm3) | ||||||||||

| < 500 | 1.40 | 0.80-2.43 | 0.236 | 1.41 | 0.86-2.33 | 0.178 | ||||

| 500-1499 | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| ≥ 1500 | 1.24 | 0.81-1.90 | 0.323 | 1.42 | 0.96-2.12 | 0.082 | ||||

| Experience | ||||||||||

| Attending physicians | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Fellow | 1.93 | 1.41-2.63 | < 0.001 | 1.92 | 1.41-2.63 | < 0.001 | 1.88 | 1.38-2.57 | < 0.001 | |

| Female | BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| < 23 | 1.66 | 1.02-2.69 | 0.041 | 1.96 | 1.25-3.10 | 0.004 | ||||

| 23-24.9 | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| ≥ 25 | 1.79 | 1.02-3.13 | 0.042 | 1.71 | 0.99-2.96 | 0.053 | ||||

| VAT volume (cm3) | ||||||||||

| < 500 | 1.54 | 1.03-2.31 | 0.034 | 1.66 | 1.17-2.35 | 0.005 | ||||

| 500-1499 | Ref | Ref | ||||||||

| ≥ 1500 | 1.31 | 0.47-3.64 | 0.606 | 1.47 | 0.55-3.96 | 0.446 | ||||

| Experience | ||||||||||

| Attending physicians | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||||

| Fellow | 1.53 | 1.08-2.16 | 0.016 | 1.52 | 1.08-2.14 | 0.016 | 1.54 | 1.10-2.17 | 0.013 |

BMI: Body mass index; VAT: Visceral adipose tissue.

DISCUSSION

We found that being female, lower or higher BMI, low VAT volume and fellow involvement were predictors of a longer CIT. In subgroup analysis by gender, lower or higher BMI and fellow involvement were predictors for prolonged CIT in both genders. However, a low VAT volume was associated with a longer CIT in only women.

In this study, female gender was identified as a predictor of longer CIT. In addition, ninety three patients of CIT more than 15 min were all women in our study. The female pelvis is deeper and more rounded than the male pelvis, which may predispose to loop formation in the sigmoid colon[16,20]. Saunders et al[20] reported total colonic length was greater in women compared to men (155 cm vs 145 cm, P = 0.005). Transverse colon length is, especially, longer in women than in men (48 cm vs 40 cm, P < 0.0001) and redundancy of the transverse colon is more frequent in women compared with that in men (62% vs 26%, P < 0.0001), which predisposes to loop formation and difficulty in passing the colonoscope in women[20]. Arcovedo et al[21] suggested that the peritoneal cavity is smaller in women, which causes a more convoluted packaging of the entire colon, which eventually forms an acute angle at the colonic flexure. A longer and more slender colonoscope could overcome those factors (longer colon length and more acute angle at the flexure) in women during colonoscopy insertion.

BMI was reported to be one of the predicting factors of prolonged CIT, with lower BMI was being associated with a difficult procedure[17,22]. These studies explained that this finding may be because of the relatively lower amount of visceral fat in patients with lower BMI. Visceral fat may allow for easier passage of the colonoscopy by supporting the colon in the pelvis and thus reducing loop formation[22]. However, another study has shown conflicting results. Jain et al[15] recently reported that BMI had a positive association with CIT for women, but had a negative association with CIT for men. The discrepancy in the association of BMI and CIT might be that the enrolled patients’ characteristics were different among studies. Jain et al[15] study excluded the patients with poor bowel preparation, a history of abdomino-pelvic surgery, and procedure done by trainees but the present study included these types of cases. In our study, when higher BMI (≥ 25 kg/m2) group was divided into overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) group, not obese group but overweight group was associated with prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis. Even though high BMI (≥ 30 kg/m2) was not significant association in univariable and multivariable analysis, there was a trend of association with prolonged CIT. The cause of these result might be the low number of high BMI (n = 45) (data not shown). BMI was used as a measure of obesity, but this may not be an accurate measure of abdominal visceral fat. BMI is an overall obesity index[23]. Men have more abdominal and visceral fat than women, in whom fat is distributed in more femoral and gluteal regions[24]. In our study, while in women BMI and VAT volume both showed an association with CIT, in men BMI could absorb the association between VAT volume and CIT.

In this study, lower VAT volume was a significant predictive factor of prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis in women. Visceral fat may provide a direct support for the colon in the pelvis, assisting for the easier passage of the colonoscope[25]. However, the association between VAT volume and prolonged CIT was not statistically significant in men. A plausible explanation about this discrepancy between the genders may be that loop formation in the sigmoid colon is more frequent without supporting visceral fat in women owing to their anatomical feature of a deeper and rounded pelvis. In addition, the increased abdominal wall musculature in men may provide more external resistance and act as an external splint to the colonoscope, preventing loop formation[17,20].

A study demonstrated that smaller WC was associated with prolonged CIT[9]. In contrast, consistent with our result, Chung et al[16] reported that there was no direct correlation between WC and CIT. It might be because WC does not seem to reflect real volume of the peritoneal cavity.

In our study, fellow involvement was significantly associated with prolonged CIT both in univariable and multivariable analysis (P < 0.001). Similar results were obtained in a few previous studies[13,17]. This can be explained by the learning curve for trainees performing the colonoscopy. Park et al[26] reported that CIT was inversely proportional to the number of colonoscopies the trainee had performed; CIT was 12 min and 8.7 min for 150 cases and 250 cases, respectively. They analyzed the factors affecting cecal intubation based on the pre- and post- colonoscopic competency of trainees. Park et al[26] reported low BMI, inadequate bowel preparation and history of stomach surgery influenced cecal intubation during the pre-competency period and a previous history of gastric operation and inadequate bowel preparation also affected cecal intubation. The present study did not completely discriminate the status of colonoscopic competency of fellow trainees. However, our training program has rules of changing the trainee when patients suffer pain or colonoscope is sluggish at the same segment.

In subgroup analysis by experience of the colonoscopist, patient age of 65 years or over (OR = 2.08, 95%CI: 1.13-3.82, P = 0.018), BMI of 25 kg/m2 or over (OR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.21-3.12, P = 0.006), and VAT volume less than 500 cm3 (OR = 1.70, 95%CI: 1.02-2.86, P = 0.044) were associated with prolonged CIT in fellow group in multivariable analysis (Supplement Table 1). Several studies have reported different results whether older age associate with prolonged CIT. A prospective study by Zuber-jerger et al[27] showed CIT was not related with age. However, consistent with our results of fellow group, a study for colonoscopy learning curves of gastroenterology fellows reported an older age was associated with a longer insertion time[28]. Length of the entire colon has been reported to increase with age, resulting in increased redundancies and loop formation[29]. Also, decreased elasticity of the colon associated with advanced age predisposes to loop formation during colonoscopy[9]. These might impede the advancement of the colonoscope, especially among fellows who lack the skills. In the attending physician group, being female (OR = 1.42, 95%CI: 1.01-2.00, P = 0.043), BMI less than 23 kg/m2 (OR = 1.79, 95%CI: 1.15-2.79, P = 0.010) and greater than or equal to 25 kg/m2 (OR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.07-2.64, P =0.024) were associated with prolonged CIT in multivariable analysis (Supplement Table 1).

In previous studies, poor bowel preparation prolonged CIT[13,30,31]. However, quality of bowel preparation was not associated with prolonged CIT in our study and several other studies[4,16]. This discrepancy might be due to different criteria for the bowel preparation state[16]. In subgroup analysis by experience of the colonoscopist, poor bowel preparation was marginally associated with prolonged CIT in the fellow group but not in the attending physician group in multivariable analysis (P = 0.056, Supplement Table 1). Consistent with our study, it was reported that poor bowel preparation was a predictive factor of difficult colonoscopy in colonoscopy trainees who lacked techniques for insertion[26].

The advantage of this study is its large sample size including various obesity indices and prospectively collected data that was retrospectively analyzed. However, there were some limitations. First, the present study was performed by a single center. However, seven expert colonoscopists performed the endoscopy and analyzed a large number colonoscopy cases. Second, factors such as pain tolerance and use of narcotic agents, which may affect difficult colonoscopy, were not assessed. Colonoscopy provokes anxiety and discomfort in some patients. Patient stress may result in increased sympathetic outflow, an increase in bowel sensitivity with a greater need for sedative medication, and decreased procedure tolerance, resulting thereby in prolonged CIT[32]. These factors should be evaluated in future studies.

In conclusion, Prediction of potentially difficult patient may help the colonoscopist decide on scheduling, sedation and vital monitoring requirements, and the need for better colonoscopic expertise. Being female, lower or higher BMI than the normal range, low VAT volume and fellow involvement were predictors of longer CIT. Among obesity indices, lower or higher BMI than the normal range and low VAT volume were associated with longer CIT. Our findings suggest a role of VAT volume, not VAT area, in colonoscope insertion for the first time.

COMMENTS

Background

Colonoscopy has been the standard examination for the screening and surveillance of colorectal cancer. Cecal insertion time (CIT) varies greatly in different cases and is considered a surrogate measure for difficult colonoscopy. It is important to identify the factors predicting longer CIT. These factors included age, gender, quality of bowel preparation, history of prior abdominal surgery, experience of the colonoscopist, diverticulosis and constipation. In addition, research on the relationship between CIT and obesity indices, such as body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), visceral adipose tissue (VAT) area and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) area, has been reported. However, the results of previous studies are conflicting. The aims of this study were to identify the factors influencing CIT and to evaluate the effect of obesity indices on CIT.

Research frontiers

Being female, lower or higher BMI than the normal range, low VAT volume and fellow involvement were predictors of longer CIT. Among obesity indices, lower or higher BMI than the normal range and low VAT volume were associated with longer CIT.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this study, its large sample size including various obesity indices (BMI, WHR, WC, VAT volume and SAT volume) and prospectively collected data that was retrospectively analyzed. Visceral fat was calculated as volume for precise evaluating the effects of VAT on CIT. They performed a subgroup analysis by gender.

Applications

The patients with female gender, lower or higher BMI than the normal range, low VAT volume may need a longer scheduled interval, sedation and vital monitoring requirements, and better colonoscopic expertise.

Terminology

Prolonged CIT: defined as longer than 10 min in CIT. VAT volume: measured as intra-abdominal fat bound by parietal peritoneum or transversalis fascia, excluding the vertebral column and paraspinal muscles.

Peer-review

The authors retrospectively reviewed the data of patients who underwent colonoscopy at a single Endoscopy Unit and retrieved data about various obesity indices, as well as specific data about the exams.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This study was approved by the institutional review board of National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC2016-0217).

Informed consent statement: This study is exempt from informed consent, since it is a retrospective study and the data collection and analysis were carried out without disclosing patient’s identity.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that there are no potential conflicting interests related to the submitted manuscript.

Data sharing statement: There are no available additional data.

Peer-review started: November 23, 2016

First decision: December 28, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2017

P- Reviewer: Christodoulou DK, Hosoe N, Zorzi M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Davila RE, Rajan E, Baron TH, Adler DG, Egan JV, Faigel DO, Gan SI, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Lichtenstein D, et al. ASGE guideline: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:546–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rex DK, Goodwine BW. Method of colonoscopy in 42 consecutive patients presenting after prior incomplete colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1148–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:169–174. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung YW, Han DS, Yoo KS, Park CK. Patient factors predictive of pain and difficulty during sedation-free colonoscopy: a prospective study in Korea. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson DB, McQuaid KR, Bond JH, Lieberman DA, Weiss DG, Johnston TK. Procedural success and complications of large-scale screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:307–314. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.121883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi Y, Tanaka H, Kinjo M, Sakumoto K. Prospective evaluation of factors predicting difficulty and pain during sedation-free colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1295–1300. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0940-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chutkan R. Colonoscopy issues related to women. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia H, Wang L, Luo H, Yao S, Wang X, Zhang L, Huang R, Liu Z, Kang X, Pan Y, et al. Difficult colonoscopy score identifies the difficult patients undergoing unsedated colonoscopy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2015;15:46. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0273-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsieh YH, Kuo CS, Tseng KC, Lin HJ. Factors that predict cecal insertion time during sedated colonoscopy: the role of waist circumference. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:215–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu CM, Lin WP, Su MY, Chiu CT, Ho YP, Chen PC. Factors that influence cecal intubation rate during colonoscopy in deeply sedated patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:76–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh SY, Sohn CI, Sung IK, Park DI, Kang MS, Yoo TW, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Jeon WK, et al. Factors affecting the technical difficulty of colonoscopy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1403–1406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein C, Thorn M, Monsees K, Spell R, O’Connor JB. A prospective study of factors that determine cecal intubation time at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:72–75. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagata N, Sakamoto K, Arai T, Niikura R, Shimbo T, Shinozaki M, Noda M, Uemura N. Predictors for cecal insertion time: the impact of abdominal visceral fat measured by computed tomography. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1213–1219. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dafnis G, Granath F, Påhlman L, Ekbom A, Blomqvist P. Patient factors influencing the completion rate in colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain D, Goyal A, Uribe J. Obesity and Cecal Intubation Time. Clin Endosc. 2016;49:187–190. doi: 10.5946/ce.2015.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung GE, Lim SH, Yang SY, Song JH, Kang HY, Kang SJ, Kim YS, Yim JY, Park MJ. Factors that determine prolonged cecal intubation time during colonoscopy: impact of visceral adipose tissue. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2014;49:1261–1267. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2014.950695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krishnan P, Sofi AA, Dempsey R, Alaradi O, Nawras A. Body mass index predicts cecal insertion time: the higher, the better. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:439–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nam SY, Kim BC, Han KS, Ryu KH, Park BJ, Kim HB, Nam BH. Abdominal visceral adipose tissue predicts risk of colorectal adenoma in both sexes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:443–450.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346–352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saunders BP, Fukumoto M, Halligan S, Jobling C, Moussa ME, Bartram CI, Williams CB. Why is colonoscopy more difficult in women? Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:124–126. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(06)80113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arcovedo R, Larsen C, Reyes HS. Patient factors associated with a faster insertion of the colonoscope. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:885–888. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JC, Messina CR, Cohn W, Gottfried E, Ingber S, Bernstein G, Coman E, Polito J. Factors predictive of difficult colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:558–562. doi: 10.1067/mge.2001.118950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Björntorp P. Obesity. Lancet. 1997;350:423–426. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04503-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krotkiewski M, Björntorp P, Sjöström L, Smith U. Impact of obesity on metabolism in men and women. Importance of regional adipose tissue distribution. J Clin Invest. 1983;72:1150–1162. doi: 10.1172/JCI111040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JC, Gonzalez JD, Messina CR, Pollack BJ. Factors that predict incomplete colonoscopy: thinner is not always better. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2784–2787. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park HJ, Hong JH, Kim HS, Kim BR, Park SY, Jo KW, Kim JW. Predictive factors affecting cecal intubation failure in colonoscopy trainees. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuber-Jerger I, Endlicher E, Gelbmann CM. Factors affecting cecal and ileal intubation time in colonoscopy. Med Klin (Munich) 2008;103:477–481. doi: 10.1007/s00063-008-1071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung JI, Kim N, Um MS, Kang KP, Lee D, Na JC, Lee ES, Chung YM, Won JY, Lee KH, et al. Learning curves for colonoscopy: a prospective evaluation of gastroenterology fellows at a single center. Gut Liver. 2010;4:31–35. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sadahiro S, Ohmura T, Yamada Y, Saito T, Taki Y. Analysis of length and surface area of each segment of the large intestine according to age, sex and physique. Surg Radiol Anat. 1992;14:251–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01794949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HL, Eun CS, Lee OY, Jeon YC, Han DS, Sohn JH, Yoon BC, Choi HS, Hahm JS, Lee MH, et al. Significance of colonoscope length in cecal insertion time. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang CM, Chiu YC, Wu KL, Tam W, Tai WC, Hu ML, Chou YP, Chiu KW, Chuah SK. Impact factors for difficult cecal intubation during colonoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:443–446. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182611c69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williams OA. Patient knowledge of operative care. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:328–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]