Abstract

AIM

To quantify the risk of gastric cancer in first-degree relatives of patients with the cancer.

METHODS

A comprehensive literature search was performed. Case-control trials comparing the frequency of a positive family history of gastric cancer in patients with gastric cancer, vs non-gastric cancer controls were retrieved. Studies with missed or non-extractable data, studies in children, abstracts, and duplicate publications were excluded. A meta-analysis of pooled odd ratios was performed using Review Manager 5.0.25. We performed subgroup analysis on Asian studies and a sensitivity analysis based on the quality of the studies, type of the outcome, sample size, and whether studies considered only first-degree relatives.

RESULTS

Thirty-two relevant studies out of 612 potential abstracts (n = 80690 individuals) were included. 19.0% of the patients and 10.9% of the controls had at least one relative with gastric cancer (P < 0.00001). The pooled relative risk for the development of gastric cancer in association with a positive family history was 2.35 (95%CI: 1.96-2.81). The Cochran Q test for heterogeneity was positive (P < 0.00001, I² = 92%). After excluding the three outlier studies with the highest relative risks, heterogeneity remained significant (P < 0.00001, I² = 90%). The result was not different among Asian studies as compared to others and remained robust in several sensitivity analyses. In the 26 studies which exclusively analysed the history of gastric cancer in first-degree relatives, the relative risk was 2.71 (95%CI: 2.08-3.53; P < 0.00001).

CONCLUSION

Individuals with a first-degree relative affected with gastric cancer have a risk of about 2.5-fold for the development of gastric cancer. This could be due to genetic or environmental factors. Screening and preventive strategies should be developed for this high-risk population.

Keywords: Gastric cancer; Risk, Relatives; Family history; Meta-analysis

Core tip: Several case-control studies have found a familial predisposition for gastric cancer. Most studies suggest that first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer are at higher risk. In this meta-analysis we aimed to quantify this risk by including case-control trials comparing the frequency of a positive family history of gastric cancer in patients with gastric cancer, vs non-gastric cancer controls were retrieved. We showed that the pooled relative risk for the development of gastric cancer in association with a positive family history was 2.35 (95%CI: 1.96-2.81). We concluded that the individuals with a first-degree relative affected with gastric cancer have a risk of about 2.5-fold for the development of gastric cancer. This could be due to genetic or environmental factors. Screening and preventive strategies should be developed for this high-risk population.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide and is the second most frequent cause of death from cancer, accounting for 10.4% of all cancer deaths[1]. Approximately 700000 people die from gastric cancer each year[2]. In 2008, about three-quarters of cases and deaths from stomach cancer occurred in low- and middle-income and middle-income countries (LMIC). Rates are also elevated in Eastern Europe including Russia, as well as certain parts of Latin America and East Asia[3]. Both environmental and genetic factors are believed to play a part in the development of gastric cancer. Environmental factors include diet and infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) have been shown to contribute to gastric cancer[4]. The incidence of gastric cancer is declining globally, principally because of the improvements in socio-economic status and partly due to widespread use of eradication therapy for H. pylori[2]. An increased intake of nitrites and nitrosamines, as well as of salted foods have also been other suggested environmental factors[5,6]. Familial predisposition has also long been considered an important factor. Several case-control studies have reported a higher rate of gastric cancer among relatives of patients than among relatives of controls, however, no guideline defines the assessment of the family history in patients with gastric cancer. A systematic review on the studies investigating the rates of genetic assessment and referral for 11 different types of familial cancer did not include gastric cancer[7]. This indicates an apparent lack of awareness of the extent of genetic susceptibility to gastric cancer. The only meta-analysis on the risk of gastric cancer in the first degree relatives of patients scrutinized the role of H. pylori concluded that first-degree relatives of patients with gastric cancer may be at higher risk of developing gastric cancer, due to indirect evidence such as higher prevalence of H. pylori, gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia[8]. We have shown an increased risk of developing gastric cancer in first degree relatives of patients by systematically reviewing the literature, however, we did not aim to perform a statistical analysis to estimate the risk[9]. The goal of this study was to measure the risk of gastric cancer in family members, by conducting a meta-analysis of published case-control studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

Electronic searches were conducted using OVID MEDLINE (1946 to December 2013), EMBASE (1980 to December 2013) and Cochrane library, and ISI Web of knowledge from 1980 to December 2013. Articles were selected using a highly sensitive search strategy, with a combination of MeSH headings and text words that included (1) gastric cancer; (2) risk factor; or (3) family history. Recursive searches and cross-referencing were carried out using a “similar articles” function; bibliography of the articles identified after an initial search were also manually reviewed. The search was not restricted to any specific language.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Case-control studies were included if they included cases diagnosed with gastric cancer and controls with diagnoses other than gastric cancer. The outcome of interest was a positive family history of gastric cancer in first or second-degree relatives. Studies with missed or non-extractable data, studies in children, abstracts, and duplicate publications were excluded.

Publication bias

No restrictions were applied in terms of language, geographical location or quality of studies. A funnel plot model was applied to explore the likelihood of publication bias. Asymmetry of funnel plot implies likelihood of publication bias.

Reliability

One of the a priori concerns was the possibility of selection bias in retrieving and evaluating the included studies. In order to reduce this bias, two independent reviewers performed the search, quality assessment and data extraction. A third reviewer was involved when a consensus could not be achieved.

Heterogeneity

Variation in the patient populations and the quality of studies was considered as an a priori source of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were predicted a priori to investigate each source.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers retrieved the data. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses was applied to evaluate the quality of observational studies[10]. The total score for this assessment tool ranged from 0 to 9. No studies were excluded based on the quality score. Studies with a score of > 5 were considered as of higher quality.

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis of pooled relative risk was performed using the Mantel-Haenszel method and Review Manager 5.0.25. The random effect model was applied. A P value of 0.05 was applied as criterion for statistical significance. I2 was generated to assess heterogeneity and was interpreted as previously described[11]. Test of heterogeneity was considered significant if the P value less than 0.10. All results are reported with 95%CI when applicable. Subgroup analysis was done on studies in patients with Asian ethnicity vs studies of patients with non-Asian origins. The following sensitivity analyses were also conducted: (1) studies with higher quality score vs those with lower quality score; (2) studies with the question of family history in gastric cancer as the primary objective vs studies in which it was a secondary objective; (3) Studies with a sample size of more than 1000; and (4) Studies on positive family history of gastric cancer in first degree relatives.

RESULTS

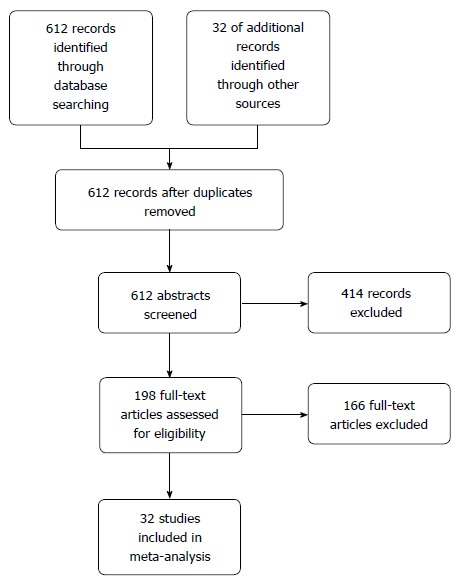

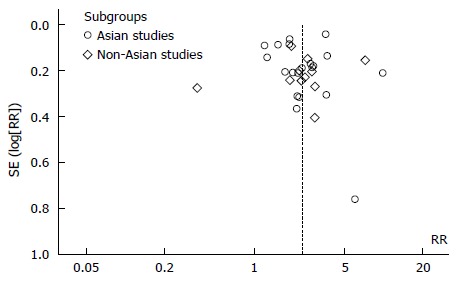

A total of 612 potential studies were identified. Thirty two studies were found to be eligible and were included in the meta-analysis (nine from Europe, nineteen from East Asian countries, one from India, one from Iran, one from Peru and one from the United States). Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram. All but three of the studies were published in English, one in Spanish and one was in Korean. The results of one of the included studies were published separately for siblings and parents[12,13] and one publication included two different studies on hospital- and community-based populations[14]. The primary objective of seventeen studies was to estimate the risk of gastric cancer in relatives of patients. This was a secondary objective in fifteen other studies. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the included studies. Figure 2 depicts the Funnel plot of the study. No visual asymmetry was observed in the Funnel plot.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Ref. | Year | Country | Controls | Type of outcome | Family history | Quality score (0-9) |

| Bakir et al[11,12] | 2000 | Turkey | HB, NC, NGC | Primary | 1st | 4 |

| 2003 | ||||||

| Brenner et al[25] | 2000 | Germany | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 5 |

| Chen et al[26] | 2004 | Taiwan | HB, NC, GC, NGI | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Chirinos et al[27] | 2012 | Peru | HB, NC | Primary | Unclear | 5 |

| Chow et al[28] | 1999 | Poland | CB, Healthy | Secondary | Unclear | 7 |

| Chung et al[29] | 2010 | South Korea | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 5 |

| Dhillon et al[30] | 2001 | United States | PB, Healthy | Primary | 1st | 7 |

| Ennishi et al[31] | 2011 | Japan | HB, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 6 |

| Eto et al[32] | 2006 | Japan | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 4 |

| Foschi et al[33] | 2008 | Italy | HB, NC | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Gajalakshmi et al[34] | 1996 | India | HB, NGC | Secondary | Unclear | 5 |

| Garcia-Gonzalez et al[35] | 2012 | Spain | CB, NGI | Secondary | 1st | 6 |

| Gong et al[36] | 2013 | South Korea | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 5 |

| García-González et al[37] | 2007 | Spain | HB, NC, NGC | Secondary | 1st/2nd | 6 |

| Hong et al[38] | 2006 | South Korea | HB, NC, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 4 |

| Huang et al[39] | 1999 | Japan | HP, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 5 |

| Ikeguchi et al[40] | 2001 | Japan | HB, NC, NGC, NGI | Primary | 1st-3rd | 4 |

| La Vecchia et al[41] | 1992 | Italy | HB, NC, NGC, NGI | Primary | 1st | 3 |

| Lee et al[42] | 2009 | South Korea | HB, NGC | Primary | Unclear | 5 |

| Li et al[43] | 2010 | China | HB, NGI | Secondary | 1st | 6 |

| Mao et al[44] | 2011 | China | HB, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 5 |

| Minami et al[45] | 2003 | Japan | HP, NC, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 5 |

| Nagase et al[46] | 1996 | Japan | HB, NC, NGC | Primary | 1st | 5 |

| Palli et al[47] | 1994 | Italy | CB, healthy | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Presson et al[13] | 2009 | Sweden | HB, CB, NC | Secondary | 1st/2nd | 7 |

| Safaee et al[48] | 2011 | Iran | HB, Healthy | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Shen et al[49] | 2009 | China | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Shin et al[50] | 2010 | South Korea | HB, NGC | Primary | 1st | 6 |

| Wen et al[51] | 2014 | China | HB + CB, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 7 |

| Yi et al[52] | 2010 | China | HB, NGC | Secondary | 1st | 5 |

| Zhang et al[53] | 2009 | China | HB, NC | Secondary | 1st | 6 |

| Zhang et al[54] | 2008 | China | HB, NC | Secondary | 1st | 6 |

HB: Hospital-based; CB: Community-based; NC: Non-cancer; NGI: Non gastrointestinal disorder; NGC: Non-gastric cancer.

Figure 2.

Funnel plot of included studies (n = 19).

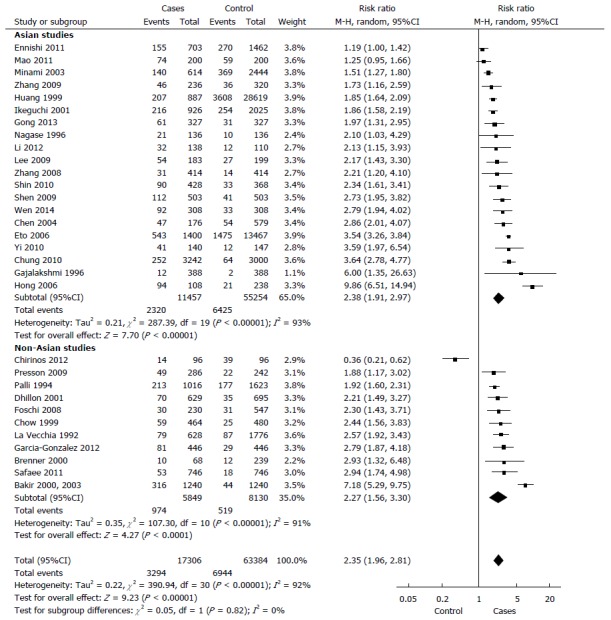

In total, 17306 cases with gastric cancer and 63384 controls. 19.0% of the cases and 10.9% of the controls had at least one relative with a diagnosis of gastric cancer (P < 0.00001). The random model Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis showed a relative risk for the development of gastric cancer in individuals with a positive family history in a first- or second-degree relative, compared to controls was 2.35 (95%CI: 1.96-2.81) (Figure 3). The Cochran Q test for heterogeneity was positive (P < 0.00001, I² = 92%).

Figure 3.

The Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis of all included studies (n = 32) with subgroup analysis of Asian vs non-Asian population.

After excluding the three outlier studies with the highest relative risks, heterogeneity remained significant (P < 0.00001, I² = 90%). When we considered the 26 studies which exclusively analysed the history of gastric cancer in first-degree relatives, the relative risk was 2.71 (95%CI: 2.08-3.53; P < 0.00001).

Subgroup analysis

Asian and non-Asian populations: There was no significant difference in studies on Asian as compared to those on non-Asian population in random model Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis (P = 0.82). The relative risk in Asian studies was 2.38 (95%CI: 1.91-2.97, P < 0.00001). The test of heterogeneity was significant within this subgroup of seven studies (P < 0.00001, I² = 93%). In non-Asian population, the relative risk was 2.27 (95%CI: 1.56-3.30; P < 0.00001). There was evidence for heterogeneity in this analysis (P < 0.00001, I² = 91%).

A sensitivity analysis was performed after excluding all studies with a total number of included individuals less than 1000 and showed that the difference between two groups remained unchanged (P = 0.31).

Sensitivity analyses

High quality vs low quality studies: Heterogeneity persisted among thirteen studies that were scored as high quality (P < 0.00001, I² = 73%) as well as among studies with lower quality scores (P < 0.00001, I² = 95%). Random model Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis showed no significant difference (P = 0.50) between the high quality [RR = 2.21 (95%CI: 1.84-2.64)] as compared to low quality studies [RR = 2.47 (95%CI: 1.87-3.27)].

Family history being the primary vs secondary outcome: Heterogeneity persisted among seventeen studies that used family history as the primary outcome (P < 0.00001, I² = 91%) as well as among studies that used it as secondary outcome (P < 0.00001, I² = 89%). Random model Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis showed no significant difference (P = 0.66) between two subgroups [RR = 2.43 (95%CI: 1.95-3.05) and RR = 2.26 (95%CI: 1.75-2.91)], respectively.

Effect of the sample size on outcome: Heterogeneity persisted among thirteen studies with a total included individuals greater than 1000 (P < 0.00001, I² = 96%). Random model Mantel-Haenszel meta-analysis showed a relative risk of 2.68 (95%CI: 2.08-3.45, P < 0.00001).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis exploring the relative risk for the development of gastric cancer among the relatives of patients. Overall, the risk is approximately 2.5 times greater in those with an affected first-degree relative than in relatives of unaffected controls. However, we observed significant heterogeneity between studies. This heterogeneity could be the result of variations in population sampling or in experimental design, but could also reflect inherent differences in the genetic composition of the studied populations. The relative risk of gastric cancer is elevated to a similar extent for first-degree relatives of patients in the different studies, but the actual risk will depend on the ethnic group and the country of residence. For example, the lifetime risk of gastric cancer is approximately 1% in Canada and the United States, but exceeds 4% in regions of China, Japan and Korea[15]. Rates are also high in Colombia, Ecuador and Costa Rica and in parts of southern and Eastern Europe, including Italy, Portugal, Latvia and Estonia. In parts of Japan, the lifetime risk of gastric cancer exceeds 10% in males and 4% in females and if the relative risk of 2.5 is applied to relatives of patients in these populations, the lifetime risk may approach 25%. In contrast, in Canada a male with a first-degree relative with gastric cancer faces a lifetime risk of about 3%[2].

Among environmental factors H. Pylori infection is directly related to gastric cancer. In a meta-analysis of prospective (cohort) studies, the OR for the association between H. Pylori infection and the subsequent development of gastric cancer was 2.36 (95%CI: 1.98-2.81)[16]. A comprehensive literature search identified 16 qualified studies with 2284 cases and 2770 controls. H. pylori and cagA seropositivity significantly increased the risk for gastric cancer by 2.28- and 2.87-fold, respectively. Among H. pylori -infected populations, infection with cagA-positive strains further increased the risk for gastric cancer by 1.64-fold (95%CI: 1.21-2.24) overall and by 2.01-fold (95%CI: 1.21-3.32) for noncardiac gastric cancer[17]. Another meta-analysis of three randomized controlled studies also showed a reduction in the risk of gastric cancer following the eradication of H. pylori infection (OR = 0.67; 95%CI: 0.42-1.07)[4]. Other environmental risk factors include a high intake of foods containing nitrite and nitrosamine, salted foods as well as decreased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables[5,6].

The genetic factors which are responsible for the familial aggregation of gastric cancer are largely unknown. Gastric cancer is one of several inherited cancer predisposition syndromes, including hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer, familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden disease, and the Li-Fraumeni syndrome[18,19]. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC) is a rare, form of gastric cancer with an autosomal dominant inheritance, which presents with early-onset, poorly differentiated, high-grade, diffuse gastric cancer that can be caused by germline mutations in CDH1 or p53 in half to two thirds of the cases[20,21]. Microsatellite instability was significantly associated with antral tumors and a positive family history of gastric cancer[20]. Increased gastric cancer risk has also been associated with polymorphic variants in interleukin-1-beta (IL-1β) and N-acetyltransferase-1 (NAT1). In one study, individuals carrying the IL-1β-31 T polymorphism were at a higher risk of gastric cancer after H. pylori infection[22,23]. This might indicate the potential interaction between environmental and genetic factors.

Our study has the limitations inherent to most case-control studies. We could not completely exclude publication bias. Although we did not limit the language of study publication and we used several search sources, all but one of our included studies is in English and some publications may have been overlooked. Unpublished data might be another source of bias. We have also provided a funnel plot to visually assess this possibility. Several studies adjusted their analyses for the effects of known or presumed environmental factors. However, in our meta-analysis it was not possible to consider possible confounders because we did not have access to the original data.

Although different case-control studies have shown a higher rate of gastric cancer among relatives of patients, no guidelines have been developed to assess systematically the family histories of individual patients with gastric cancer. In 2008 Asia-Pacific consensus guideline on preventing gastric cancer considered a positive family history of gastric cancer an important risk factor[24]. A systematic review on cancer genetic assessment provided risk assessment and referral rates for 11 types of cancer known to show evidence of familial clustering but did not include gastric cancer[7]. This indicates a possible lack of awareness of the extent of genetic susceptibility for gastric cancer.

In summary, there is strong evidence that gastric cancer has a familial component. The relative risk of 2.5 reported here is larger than that observed for most adult forms of solid cancers, with the exception of ovarian cancer. Improving socioeconomic status and eradication of H. pylori infection might, in long term, decrease the risk however molecular epidemiology studies, such as genome-wide association studies, may help to identify the responsible genetic factors.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide and is the second most frequent cause of death from cancer responsible for approximately 700000 death each year. The risk of development of gastric cancer in relatives of patients with this cancer is not clear.

Research frontiers

The estimated risk of gastric cancer will help in development of preventive and screening strategies for the relatives of patients.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first meta-analysis in quantifying the risk of developing gastric cancer in relatives of patients with this cancer.

Applications

The obtained information could be used in developing screening guidelines.

Peer-review

Congratulations for the quality of the work. In my opinion there was an overestimation of Helicobacter pylori and no reference to alcohol abuse and the tobacco dependency.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Canada

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data sharing statement: No additional data is available.

Peer-review started: November 2, 2016

First decision: December 19, 2016

Article in press: March 15, 2017

P- Reviewer: Bang YJ, Caboclo JLF S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Parkin DM. International variation. Oncogene. 2004;23:6329–6340. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Agency for Research on Cancer. GLOBOCAN database. IARC, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Minardi ME, Bazzoli F. Systematic review: Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:133–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsugane S, Sasazuki S. Diet and the risk of gastric cancer: review of epidemiological evidence. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:75–83. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0420-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakszyn P, Gonzalez CA. Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4296–4303. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Featherstone C, Colley A, Tucker K, Kirk J, Barton MB. Estimating the referral rate for cancer genetic assessment from a systematic review of the evidence. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:391–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rokkas T, Sechopoulos P, Pistiolas D, Margantinis G, Koukoulis G. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric histology in first-degree relatives of gastric cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1128–1133. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283398d37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yaghoobi M, Bijarchi R, Narod SA. Family history and the risk of gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:237–242. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells GA, Shea B, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakir T, Can G, Erkul S, Siviloglu C. Stomach cancer history in the siblings of patients with gastric carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000;9:401–408. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakir T, Can G, Siviloglu C, Erkul S. Gastric cancer and other organ cancer history in the parents of patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003;12:183–189. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200306000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson C, Engstrand L, Nyrén O, Hansson LE, Enroth H, Ekström AM, Ye W. Interleukin 1-beta gene polymorphisms and risk of gastric cancer in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:339–345. doi: 10.1080/00365520802556015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Volume ViII. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helicobacter and Cancer Collaborative Group. Gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori: a combined analysis of 12 case control studies nested within prospective cohorts. Gut. 2001;49:347–353. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Sumanac K, Irvine EJ, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between cagA seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1636–1644. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch HT, Smyrk T. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome). An updated review. Cancer. 1996;78:1149–1167. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6<1149::AID-CNCR1>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson P, Lynch HT. Extracolonic cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1993;71:677–685. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930201)71:3<677::aid-cncr2820710305>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilford P, Hopkins J, Harraway J, McLeod M, McLeod N, Harawira P, Taite H, Scoular R, Miller A, Reeve AE. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392:402–405. doi: 10.1038/32918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamada H, Shinmura K, Okudela K, Goto M, Suzuki M, Kuriki K, Tsuneyoshi T, Sugimura H. Identification and characterization of a novel germ line p53 mutation in familial gastric cancer in the Japanese population. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2013–2018. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottini L, Palli D, Falchetti M, D’Amico C, Amorosi A, Saieva C, Calzolari A, Cimoli F, Tatarelli C, De Marchis L, et al. Microsatellite instability in gastric cancer is associated with tumor location and family history in a high-risk population from Tuscany. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4523–4529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Omar EM, Carrington M, Chow WH, McColl KE, Bream JH, Young HA, Herrera J, Lissowska J, Yuan CC, Rothman N, et al. Interleukin-1 polymorphisms associated with increased risk of gastric cancer. Nature. 2000;404:398–402. doi: 10.1038/35006081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fock KM, Talley N, Moayyedi P, Hunt R, Azuma T, Sugano K, Xiao SD, Lam SK, Goh KL, Chiba T, et al. Asia-Pacific consensus guidelines on gastric cancer prevention. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:351–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner H, Arndt V, Stürmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Dhom G. Individual and joint contribution of family history and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:274–279. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000115)88:2<274::aid-cncr5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen MJ, Wu DC, Ko YC, Chiou YY. Personal history and family history as a predictor of gastric cardiac adenocarcinoma risk: a case-control study in Taiwan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1250–1257. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chirinos JL, Carbajal LA, Segura MD, Combe J, Akiba S. [Gastric cancer: epidemiologic profile 2001-2007 in Lima, Peru] Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2012;32:58–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chow WH, Swanson CA, Lissowska J, Groves FD, Sobin LH, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A, Radziszewski J, Regula J, Hsing AW, Jagannatha S, et al. Risk of stomach cancer in relation to consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, tea and coffee in Warsaw, Poland. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:871–876. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990611)81:6<871::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung HW, Noh SH, Lim JB. Analysis of demographic characteristics in 3242 young age gastric cancer patients in Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:256–263. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dhillon PK, Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Chow WH, Risch HA, Gammon MD, Mayne ST, Stanford JL, Schoenberg JB, Ahsan H, et al. Family history of cancer and risk of esophageal and gastric cancers in the United States. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:148–152. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ennishi D, Shitara K, Ito H, Hosono S, Watanabe M, Ito S, Sawaki A, Yatabe Y, Yamao K, Tajima K, et al. Association between insulin-like growth factor-1 polymorphisms and stomach cancer risk in a Japanese population. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:2231–2235. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02062.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eto K, Ohyama S, Yamaguchi T, Wada T, Suzuki Y, Mitsumori N, Kashiwagi H, Anazawa S, Yanaga K, Urashima M. Familial clustering in subgroups of gastric cancer stratified by histology, age group and location. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foschi R, Lucenteforte E, Bosetti C, Bertuccio P, Tavani A, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Family history of cancer and stomach cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1429–1432. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gajalakshmi CK, Shanta V. Lifestyle and risk of stomach cancer: a hospital-based case-control study. Int J Epidemiol. 1996;25:1146–1153. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-González MA, Quintero E, Bujanda L, Nicolás D, Benito R, Strunk M, Santolaria S, Sopeña F, Badía M, Hijona E, et al. Relevance of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 gene polymorphisms to gastric cancer susceptibility and phenotype. Mutagenesis. 2012;27:771–777. doi: 10.1093/mutage/ges049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gong EJ, Ahn JY, Jung HY, Lim H, Choi KS, Lee JH, Kim DH, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, et al. Risk factors and clinical outcomes of gastric cancer identified by screening endoscopy: a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:301–309. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.García-González MA, Lanas A, Quintero E, Nicolás D, Parra-Blanco A, Strunk M, Benito R, Angel Simón M, Santolaria S, Sopeña F, et al. Gastric cancer susceptibility is not linked to pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokine gene polymorphisms in whites: a Nationwide Multicenter Study in Spain. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1878–1892. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong SH, Kim JW, Kim HG, Park IK, Ryoo JW, Lee CH, Sohn YK, Lee JY. [Glutathione S-transferases (GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1) and N-acetyltransferase 2 polymorphisms and the risk of gastric cancer] J Prev Med Public Health. 2006;39:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang X, Tajima K, Hamajima N, Inoue M, Takezaki T, Kuroishi T, Hirose K, Tominaga S, Xiang J, Tokudome S. Effect of life styles on the risk of subsite-specific gastric cancer in those with and without family history. J Epidemiol. 1999;9:40–45. doi: 10.2188/jea.9.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeguchi M, Fukuda K, Oka S, Hisamitsu K, Katano K, Tsujitani S, Kaibara N. Clinicopathological findings in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma with familial aggregation. Dig Surg. 2001;18:439–443. doi: 10.1159/000050190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.La Vecchia C, Negri E, Franceschi S, Gentile A. Family history and the risk of stomach and colorectal cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:50–55. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920701)70:1<50::aid-cncr2820700109>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DS, Yang HK, Kim JW, Yook JW, Jeon SH, Kang SH, Kim YJ. Identifying the risk factors through the development of a predictive model for gastric Cancer in South Korea. Cancer Nurs. 2001;32:135–142. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181982c2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, He W, Liu T, Zhang Q. A new cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene variant in the Han Chinese population is associated with an increased risk of gastric carcinoma. Mol Diagn Ther. 2010;14:351–355. doi: 10.1007/BF03256392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mao XQ, Jia XF, Zhou G, Li L, Niu H, Li FL, Liu HY, Zheng R, Xu N. Green tea drinking habits and gastric cancer in southwest China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:2179–2182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minami Y, Tateno H. Associations between cigarette smoking and the risk of four leading cancers in Miyagi Prefecture, Japan: a multi-site case-control study. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagase H, Ogino K, Yoshida I, Matsuda H, Yoshida M, Nakamura H, Dan S, Ishimaru M. Family history-related risk of gastric cancer in Japan: a hospital-based case-control study. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:1025–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb03104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palli D, Russo A, Ottini L, Masala G, Saieva C, Amorosi A, Cama A, D’Amico C, Falchetti M, Palmirotta R, et al. Red meat, family history, and increased risk of gastric cancer with microsatellite instability. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5415–5419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Fatemi SR, Maserat E, Zali MR. Family history of cancer and risk of gastric cancer in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:3117–3120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen X, Zhang J, Yan Y, Yang Y, Fu G, Pu Y. Analysis and estimates of the attributable risk for environmental and genetic risk factors in gastric cancer in a Chinese population. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2009;72:759–766. doi: 10.1080/15287390902841599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shin CM, Kim N, Yang HJ, Cho SI, Lee HS, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Stomach cancer risk in gastric cancer relatives: interaction between Helicobacter pylori infection and family history of gastric cancer for the risk of stomach cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e34–e39. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a159c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wen YY, Pan XF, Loh M, Yang SJ, Xie Y, Tian Z, Huang H, Lan H, Chen F, Soong R, et al. Association of the IL-1B +3954 C/T polymorphism with the risk of gastric cancer in a population in Western China. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:35–42. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283656380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yi JF, Li YM, Liu T, He WT, Li X, Zhou WC, Kang SL, Zeng XT, Zhang JQ. Mn-SOD and CuZn-SOD polymorphisms and interactions with risk factors in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4738–4746. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i37.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q, Li Y, Li X, Zhou W, Shi B, Chen H, Yuan W. PARP-1 Val762Ala polymorphism, CagA+ H. pylori infection and risk for gastric cancer in Han Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:1461–1467. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9336-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang P, Di JZ, Zhu ZZ, Wu HM, Wang Y, Zhu G, Zheng Q, Hou L. Association of transforming growth factor-beta 1 polymorphisms with genetic susceptibility to TNM stage I or II gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:861–866. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyn111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]