Abstract

We are interested in the kind of well-being that can occur as a person approaches death; we call it “existential maturity.” We describe a conceptual model of this state that we felt was realized in an individual case, illustrating the state by describing the case. Our goal is to articulate a generalizable, working model of existential maturity in concepts and terms taken from fundamentals of psychodynamic theory. We hope that a recognizable case and a model-based way of thinking about what was going on can both help guide care that fosters existential maturity and stimulate more theoretical modeling of the state.

Keywords: : existential maturity, human development, psychodynamic perspective, terminal illness

Introduction

Our Purpose

Sometimes patients say striking things. Phrases such as “Cancer is the best thing that ever happened to me” are sometimes encountered. Similarly, patients' loved ones sometimes say things such as “Accompanying him on his last journey is the most inspiring thing I have ever done.” Sometimes palliative care clinicians say equally arresting things such as “I could never find the vitality that we have in palliative care in another medical discipline; it comes from the people we care for.” We think that the phenomena deserve direct inquiry.

Cicely Saunders and other pioneers founded the modern field of hospice and palliative care on the conviction that the “total pain” that characterized too many people's last stage of life was treatable. She also observed that how a person dies can make a difference to the bereaved people for the rest of their lives.1 In the same generation, Elizabeth Kubler-Ross2 identified stages of adjustment to dying, and Joan and Erik Erikson identified chronology-based stages including the final stages. When Jimmie Holland and others started the field of psychooncology, they set about finding ways to help seriously ill people find psychosocial well-being alongside the physical aspects that palliative care was beginning to treat effectively.3,4 Research has been able to develop quality of dying scales5,6 as well as theory-based empirically tested protocols and approaches such as Harvey Chochinov's internationally tested Dignity Therapy7 and William Breitbart's Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy,8 and Vicki Jackson9 has described prognostic awareness as a feature of quality dying.

We are interested in what this state of well-being is as a whole. Is it a state or a stage with innate developmental capacities and triggers? Can anyone achieve it? How is it achieved and by whom and how and what happens if it goes missing or awry? For ease of reference, we call this way of being “existential maturity.”10 Yet, even with a name, the phenomenon of existential maturity is, at the moment, perceived in unique persons. Therefore, we now describe a conceptual model we felt particularly was realized in an individual case with a goal of articulating a generalizable model that could form the basis for future research. The model is drawn from observations and conversations from colleagues, patients, family members, and others, and it is described in concepts and terms taken from fundamentals of psychodynamic theory. It is intended as a working model; that is, it is a set of hypothetical constructs subject to modification based on new insight. Our hopes for this article are that a recognizable case and a model-based way of thinking about what was going on in one case can both help guide effective care and generate new perceptions that will create modified, improved modeling and caring.

What Is Existential Maturity?

We suggest that existential maturity is a state that is triggered by facing mortality, one's own or others', or from the culture or a combination. We observe that it can occur in all ages, including children. Wordsworth arguably captured this state in a young girl in his poem “We are Seven”11; and one of the few cases in the psychoanalytic literature dealing with a child who had to face his own mortality can be interpreted as the child struggling toward existential maturity.12 It is rendered differently in each person, and it can occur in someone healthy and in someone terminally ill or accompanying someone terminally ill. In this sense, we think of it as not only a state but also a stage like developmental stages. Developmental stages such as latency or adolescence or generativity are characterized by recognizable ways of being (e.g., obedience in latency, rebellion in adolescence, and giving from the self in generativity) and seem to depend on critical “ingredients,” relational and individual, but they are rendered differently in each person.13,14

We think of existential maturity as a type of steady state or dynamic integration of key aspects of a person's being and of personal interactions—dyadic, in family groupings, and in community. In keeping with foundational thinking by Kubler-Ross,2 we see that death is a central part of this balance. That reality can be unspeakably painful, but it is also integrated with the rest of life and the greater world. This way of being also seems particularly capable of love and finds or creates meaningful value, tenderness, and acceptance, even along with other emotions that may be passionate, turbulent, and pained. We have wondered whether expecting death lifts inhibitions that impeded loving relationships before leaving people free to relate and love fully. We have also observed that often people have not known how to think about, feel around, and relate to death; as they learn, they seem to achieve needed skills in approaching it.

In this article, we draw from many such observations and offer this model by describing features and potential mechanisms as they seem evident in one couple's experience. Our hope is that this generates discussion and attention within the scholarly and clinical community as all features are subject to adjustment based on further experience and theoretical analysis. But as with other hermeneutic aspects of life, although some underlying principles may be discernable, they are rendered uniquely in the lived experiences of different patients and families. The uniquely lived experience is contributed by the writings of the surviving member (S.B.S.) of this couple. The underpinning principles are offered by the rest of us.

The Case

Alan was diagnosed with stage IV pancreas cancer within two years of marriage to Sarah. They had little preparation for what was to quickly change their lives. Alan was 36 years old, a regular runner in excellent shape. Alan experienced constipation on a four-day hiking trip, so he went to a local ER on the advice of his doctor who wondered whether he might have kidney stones. Within two weeks, they had moved states for treatment at a major cancer center. Over the next nine months, Alan and Sarah spent more than 40 nights in hospitals over the course of eight admissions. He entered home hospice on January 3, 2015 and died on February 21, 2015.

The Process and Conceptual Perspective

L.L.E. was one among others who accompanied Alan and Sarah during this time as a friend and confidant. From diagnosis on, we stayed in touch by phone and in person and through a website designed for use by friends and family (Caringbridge). Sarah and L.L.E. worked closely together in what emerged as the present writing project, and L.L.E. engaged with her colleagues J.H. and N.R. during the writing process. Sarah and Alan chose to share their experience with the awareness that an article such as this might result that could contribute to the field and ultimately help others. It was not a “good” journey in that they would never have wished the disease upon themselves or anyone else, nor was it easy—“and yet it was a blessing,” as Sarah later put it. Sarah and Alan set their intention to make it the best journey it could be for them, and—with all its difficulties—they accomplished that. As we reviewed what transpired with a view to describing our model through it, we refined our construct and adjusted our ideas about how existential maturity is reached and what functions it serves for the dying people and their loved ones. This process of experience, conceptual formulation, and revision that we did for this article is the beginning of our anticipated longer process.

Choosing Psychodynamic Theory To Frame the Model

We have chosen a psychodynamic perspective to frame this model because psychodynamic theory provides a constellation of theoretical perspectives about how the mind works. It includes classical and ego psychology, self-psychology, object relations, developmental and attachment theory, as well as neuropsychoanalysis and neuropsychology. Behaviors, ways of thinking, and affect states are not so much managed as understood and reworked. Psychodynamic psychotherapists work with patients to foster transferential relationships that become the milieu from which self-understanding and reworked development and healing from psychological injury can occur. Psychoanalysts have successfully used the psychoanalytic process to support patients facing terminal illness.15,16 Although psychodynamic approaches may not be suited to all people, a comprehensive review of the literature suggests that perceptions of its outdatedness are incorrect and its outcomes are generally better and longer lasting than behavioral approaches.17 Although efficacy is one reason for choosing this area of psychology for our model, we also choose it for its ability to identify underlying dynamic processes in the human mind; as if one can understand that, tailoring to the particular needs, strengths, and challenges of each person in his or her own context is possible. At the same time, we recognize that such personalized approaches based on a psychodynamic model may include behavioral work or medication management that can also be crucial.

Attaining Existential Maturity

We think that existential maturity is attained in much the same way that other stages or states of being are attained. That is, from a triggering and fostering of an innate potential for that state. Development of innate capacity does not occur by superimposition or even by guidance as much as by discovery within a suitable environment. Donald Winnicott talked about the “good enough mother” and optimal frustration as a way to understand how manageable challenges prompt a level of response that does not overwhelm a child and shut down processing nor leave the child unengaged but that engenders adaptation and development.18 This model of developing innate capacity to cope with reality seems to apply to adults too.

How It Begins

Existential maturity seems to start with confronting and figuring out how to think and feel about death. For some this starts early; perhaps death was integrated into cultural or religious rituals that they took in and understood, or perhaps they experienced a death early on, taking part in related activities. Children seem to have a natural interest in death around three to five years old, noticing dead insects, birds, plants, and so on. It seems there is a natural priming of a thoughtful relationship with life's finitude. How much it is developed by experience, culture, and conversation, and how much it is avoided by culture or personal dispositions varies widely.

But for those who have not much faced death and even for those who have, when it comes up in a personal way, people are often plunged into grappling with the reality as they never have before. It is often a “wordless state” in which people can feel deeply, terrifyingly alone. It can even seem somehow offensive when people try to reach out to the person who is struggling using ordinary words of sympathy or inquiry. Weeks after Alan was diagnosed, Sarah expressed her experience of this by quoting in a message to family and friends from a poem by Carole Satyamurti:

“How are you?

When he asked me that

what if I'd said

rather than ‘very well,’

‘dreadful—full of dread’?

Since I have known this

language has cracked …”

Such a reaction to finding oneself in a terrible situation is both well known and little understood. People describe it as like bootstrapping from nothing, like “holding blackness,” like “being jelly.” Often, we hear a patient's greatest agony in words as simple as “What's happening?” This state threatens to be overwhelming. And some do not manage to find words or to adapt to the harsh reality; they take a road of denial, avoidance, or use some related effort to make it disappear. It is not easy to reach a person in a way that is ego syntonic—in synch with what he or she can take in—and does not create counter-therapeutic defensive reactions such as withdrawal or projection of blame. But it is possible and it is tremendously therapeutic because this is a state of great suffering.

This state may be what Kubler-Ross described as “immobilization.” But we think it possible to interpret her next three phases of denial, anger, and bargaining—and perhaps immobilization too—as psychological defenses; as efforts to make mortality go away, be someone else's problem, or something that the superego will solve. The core self has been mortally injured and some repair is needed; the usual defenses are tried. How they are engaged and how they are matched by other responses is all important.

For Alan and Sarah, confronting their situation was navigated between the two of them in a manner partly captured by Sarah's recollection of their first exchange about cancer in the emergency room. Sarah's first response was a kind of acknowledged naivety or something like “disavowal”; Alan, who had worked in the medical industry, seemed to be clear eyed and drawing already from a deeply engaged kind of loving care—perhaps his primary way of coping:

[H]e had thought maybe he had kidney stones […, but the ER doctor] said “I have bad news. You have stage four pancreatic cancer.” [H]e turned and he looked at me and he said “Sarah, do you have any idea what that means?” And I said: “No.” He looked back at the doctor and said: “Could you explain it to her?” He knew what pancreatic cancer meant. I didn't.

How It Continues

We think this state of wordless anxiety, experienced as something like falling aloneness, freezing or dread, has common features with the state humans are in when we confront other stark realities of life. Moving from the initial confrontation to working with it seems to have two necessary parts. One part entails taking in the experience by having feelings and thoughts about it. Having feelings and thoughts means knowing the feeling and being able to think about it enough to express it—in pictures, in words, in sounds, body language, actions, or other ways—a kind of mental representation of experienced reality that can be communicated and returned to in one's mind. The other part entails connecting this to an experience of relatedness; the sensation stays one of falling aloneness until someone (and/or perhaps some dialogic relatedness of an inner nature) can together create and hold some kind of understanding.

These are states that Melanie Klein and Winnicott delineated using their work with infants and children. Klein emphasized the aggression and Winnicott the terror. How aggression and terror relate at a deep level need not concern us here. Because, out of these deeply thoughtful ways of understanding how our minds respond to harsh realities come some remarkably elegant, simple notions that explain a lot about how we humans are and how we adapt and grow, not only in infancy and childhood but also throughout life.

Oscillating

First, as Klein set out for infants, humans approach existential matters—life and death, togetherness and separation, and identity and difference—in a binary manner. She noted that we oscillate between comfort and horror, contentment and anxiety, togetherness and isolation, synthesis and fragmentation, feeling replete and longing, and being at ease and aggressively activated. This is our fundamental process for taking in an experienced reality. By oscillating back and forth, we seem to create a representation of the reality in our mind that we can settle into and use.

One example of this high-energy seeking followed by acceptance and “working with” was described by Sarah, recalling their phase after the diagnosis:

From his professional work in the healthcare industry, Alan knew how serious this diagnosis was and the efficacy of existing treatments. He was terrified, and used the energy generated to activate a network to identify all options. Between the midnight when we heard the CT results in the ER and 2am that morning as we were being transferred to an inpatient room, Alan made probably 20 phone calls to identify ongoing trials and treatment options. Within 2 weeks, we had made appointments at 4 cancer centers and booked a complex set of travel logistics. The night before the first, we spoke with yet another expert who I clearly remember saying: “You are in crisis. When people are in crisis, they fall back on whatever they do best, and for you it's finding experts. Get 2 or maybe 3 opinions, think about what is right for you and your family right now, and then let yourself be the patient.”

Except for the times when he was actively using the enormous energy generated from the terrible set of limited choices we were facing, Alan was able to be just a person, let himself relax into being taken care of. He partnered with and listened to the doctors he respected and came to feel a great deal of closeness with. Alan only ever used the words “pancreatic” or “cancer” when reaching out for experts (both initial treatment and upon exploring second-line options). I never ever heard him use either word in any other context, or ever with a friend.

A holding presence

Second, as Winnicott and John Bowlby understood, we do this oscillation in relation to someone to whom we are attached.19 This attachment and interaction create continuity between the two states of comfort and horror. Without a relationship in which both experiences are witnessed and cared for, the back and forth is less successful; existential development is arrested. Attachment studies have also starkly demonstrated that primate infants are psychosocially severely damaged if they are only provided with physical needs and not relational contact.20 The need for someone—someone safe, understanding, and caring—with whom to do this deep existential work parallels how important it is to have a fellow journeyer for those facing life-threatening illness. Perhaps for people with a developed “I-thou” internal life, some of the product of accompaniment can come from internal dialogue in solitude.21 But some safe “containing environment” that allows the oscillation to process is needed. Perhaps this was the oscillation that Sigmund Freud observed in his grandson who was missing his mother and who comforted himself in his grandfather's presence by playing a game of throwing and reeling back in his toy, coming to terms with how return follows loss and so on.22 This aspect of our model of human nature can explain part of why dying alone is among the greater fears held by many.

Acting intuitively, Sarah and Alan proactively created a circle of people “on the inside” as they called it, and politely but assertively kept others out. This was a time for people who could be emotionally poised and available but not invasive in the presence of aggressive illness and gentle dying. Sarah wrote later:

We were incredibly fortunate to dwell inside the power of loving conversations. We had “third ear” in the early whirlwind when emotions are so high that we know you can't trust your own ability to process–someone we trusted to guide us through the intensity of a powerful decision rubric, creating space for tender, honest, and clarifying discussions about how to name and whole-heartedly continue pursuing life goals should prognosis, burdens of illness, and level of independence shift; encouragement, from the very beginning, to find our own voice. We sought and created a path of bringing in and holding love, of entering into treatment that would minimize the burdens of disease and maximize our ability to be in the world.

Finding expression

A third profound notion has been described by Wilfred Bion about the importance of expression.23 This phenomenon was crucial for Sarah and Alan. In the interaction between the sufferer and the accompanier, something important happens when expression of the experienced state occurs. The process of expression seems to allow a way of living with the reality. It is perhaps encoded, and the mind can handle it. Being able to articulate and communicate the experience, usually verbally but perhaps in some other artistic or enacted way that is received, seems to allow a connection between the raw affective state and the integrated articulate state. Whatever the mechanism, Sarah described exchanges she and Alan had with friends and relatives where she had a

palpable remembrance of words and phrases that were shockingly wrong and then the exquisitely considered, significantly shifted, re-embodied kind of space I needed to go into to find words and phrases that could gesture towards a reality that somehow was not captured quickly.

Still early in the process, Sarah and Alan used those emerging expressions and understandings to create a rubric to guide them. From this rubric of goals and values and scenarios, they were able to generate advance care plans that guided current as well as later decisions and to generate spreadsheets of needs that friends could meet—and that ended up bringing them new and precious friends who rapidly joined their “inner circle” of fellow journeyers.

What It Entails

It is one thing to describe and another to find in oneself what it takes or to allow oneself to do the work of becoming existentially mature. Here, we try to identify what is entailed in doing the oscillating, being held, and finding expression.

Facing mortality entails experiencing ultimate vulnerability. The mortal threat to the self that is presented by terminal illness seems to trigger a dramatic return to elemental states or fundamental personal structures and an urgent need for a trustworthy person with whom to process, especially early on in the process of attaining existential maturity.

The person expecting death faces loss of everything he or she has known in life. The accompanying person has anticipatory grief and then bereavement. Freud described mourning as a desired and needed adaptation to loss that allowed forward movement and its absence or defective process he called melancholia that left people stuck with some debilitating psychological symptom.24 Understanding what constitutes the actual process of mourning to avoid melancholic maladaptive responses is important.

“Regressing” to find capacity to adapt

Psychotherapists have long observed that when a therapeutic relationship is underway, the person is “regressed” to earlier stages of development; this is the state that allows the therapist to understand what psychological resources the person has been using and to help repair and develop their resources. The therapist is able to work with the person in the regressed state to cocreate more developed ways of experiencing and coping.25 Initially considered a kind of movement along a linear developmental line, it developed into a more useful appreciation of how people turn inward to their emotional and relational resources, including empathy and to the capacity to create expressions and reconstruct themselves.26–28

The vulnerability of facing mortality may not entail exactly the same regression as that which appears in the psychodynamic therapeutic relationship by which different needs emerge for care; indeed all regressions are different. The similarity is that a need triggers the person's coping approaches; some may be well evolved, others less or not. Existential challenge from mortality triggers the need for coping in the most profound and global way of all.

Whatever a person's coping structures are, that is the equipment he or she must use to face mortality. Every person arrives at his or her personal state according to the inevitable combined ingredients of inherent capacity and the experiences that fostered or stunted development of those capacities. The skills used to pilot a person's life of assumed health are brought to bear in facing death. We particularly refer to the emotional and experiential and relational skills.

This way of thinking about where a person is can be of great importance as the practitioner or a loved one tries to “find” and care for him or her. For instance, if an ordinarily skilled person is struggling to take in what is happening, leaving him or her to make a decision in the effort to be respectful may instead feel to the person like abandonment; walking the person through step-by-step explanations might work better. Or if a person is relying on early defenses of splitting and externalizing, trying to make peace by explaining the viewpoint of the other may feel like criticism; sympathizing with how hard everything is right now may allow the person the resilience to use those coping mechanisms less.

Alan was sometimes the one who “found” Sarah, and held her, often with humor, while she adjusted yet one more time to the harshness. Sarah wrote of one such time in their online updates:

Alan is transitioning. When he rests, his sight rests though his lids no longer have the energy to completely cover the eyes. Walking is strenuous. Gathering gumption to stand takes ten or twenty seconds. Rolling from back to side in bed is sometimes just too complicated. It's an effort to talk. Alan sleeps many hours at night and wakes for an hour or so four or five times during the day.

Alan to me, just before bed: “How are you?” Me: “Sad.”

I am sad. I should be sad, we are sad. Now, I know “sad” is such a simple word, but you all know how much it contains and you who know Alan know how he brings forth so much from simple words used simply and sincerely.

Alan, concerned. Me, revised: “Sad but ok.”

Also true. Ok because we are where we are and aren't pretending to be somewhere else. Ok because this time is actually an incredible gift. Ok because I hope all of us, everyone everywhere, has the blessing Alan is experiencing—living a full life; having the opportunity to and actually putting affairs in order; having the conversations that matter; being able to say intentional goodbyes; knowing fully that you are surrounded by love and, in leaving this world, being in a special position to call forth, name and share love; being relatively free from pain and discomfort. And, for me: ok, because I know these are true for Alan and that they will be a foundation to which I can always return and from which I will go forward.

Alan, probing: “Are you sad about Bruno?” Me: “Yes, but no.”

Ah, Bruno. I give us so much credit for being willing to try something new now. Bruno didn't work out. Perhaps not unexpected. We were supposed to get a dog back in October, but there were issues. We are left to imagine the scene: The day after someone officially enters into hospice, they adopt a dog who had lived seven years in various circumstances then raced through two impressive-but-wholly-insufficient-weeks preparing to be a certified service animal (which he was). Nice idea, but at the end of the day, it was a lot to handle for any one and any dog (let alone a sweet but stubborn basset hound).

Alan: “So, are you sad about the laundry?” Me: “No.”

Now I know Alan is just trying to goad smiles out of me. Laundry isn't my favorite thing of course, but it's certainly not making me sad. Happy, rather, since I finally got a chance to do a load today. I get the game.

Alan: “Well, then… what's there to be sad about?”

Well, good point, my dear. Good point.

In another journal entry, Sarah wrote:

How is he? Alan eats, but his body can't fully absorb the nutrients. He drinks, but fluid collects in his belly with thirst unsated. He folds thin thigh over thin thigh that once were thickly muscled; his numb hands fumble. He walks with labored breath and easily lulls to rest. He is sad, deeply fearful, devastated that the averages he adds up are all painfully too short. The questions he asks hurt yet also ring true and are open-eyed and brave; they cut to the heart of mortality.

Until Alan's struggles, I had never understood a prayer in Judaism one says after relieving oneself. It begins with a blessing “Who fashioned the human being intricate in design/created many orifices and cavities” and continues with an acknowledgment of what is impossible “were one of them to be ruptured or blocked…” Sometimes I go to the bathroom and hardly pay attention, then am pierced by guilt. I'm of-course-grateful but fiercely angry that my body can just do things we all wish so fervently his could.

In this entry, we can see that Alan's ability to return to the coping strength offered by Sarah's “wrap around” love allowed him to be clear eyed about the totality of his life's end. Sarah, for her part, drew coping strength from acknowledging the tentativeness of life and from the ability to be grateful (for her life) and angry (for his dying).

Other moments would likely capture different states of need and coping resources. But these two paragraphs capture something unique about Alan in his task and Sarah in hers. Alan faced the prospect of total loss in the embrace that perhaps only love can offer—from infants who face their first existential fears in their mother's embrace to children being tucked in after a nightmare sent them to the parental bed in fear, to friends listening to one another's distresses and “getting it,” and to adults holding each other in tenderness—love can make staring at mortality bearable. In those embraces, people can be utterly vulnerable and without capacity and yet fully vital and safe. Sarah, for her part, faced the horribleness that she was going to live on when Alan died. She could not afford the complete vulnerability that Alan could not avoid; she was going to need strength in anger and passionate longing. This was the psychological place that allowed her to do what she needed to do, which was to love Alan. More and different challenges with their own necessary psychological responses lay ahead for her.

Creating the internal structures

Heinz Kohut's ground-breaking work to describe how the self develops its structure can be very helpful to the fellow journeyer in meeting the person where he or she is at and in offering a helpful response, as can writings by Margaret Mahler and Winnicott.29,30

Within the context of a holding relationship or containing environment—a safe space in which it is alright to explore fearsome possibilities, to fragment and come together, and to regress and regrow—a person can do what we can call “transitional work.” By calling this transitional work, we make deliberate allusion to the Winnicottian notion of a transitional space to experience new realities. The person facing mortality must experiment, bit by bit, again and again, with how the reality plays out before returning to the tenderness of the personal space to “digest” what has been found.

This can be found in a person, in rituals, and in community events. However, an essential component appears to be a person who is admired and who reciprocally has empathic appreciation—a kind or loving eye for the exploring person. This person who is coming to understand arriving death derives strength, calmness, and wisdom from that admired, empathic person. Perhaps this emotional posture in the exploring person that Kohut called an idealizing transference allows the level of trust that is necessary for this vulnerable work. If the trusted person listens and reflects back to or mirrors for the exploring person the new experience that is being expressed, then the work of “metabolizing” or processing in a dialectical relationship the emotions and new or difficult reality is helped.

For adults, a “transitional object” or endorsed “transitional space” can be created by a blessing or endorsement to do something. The person in need of a transitional object to have the strength to go from the security of before to the next phase finds that strength in the words or meaning held in mind.

Alan and Sarah were probably one another's transitional object, as were other members of their “inner circle,” each in different ways and at different times. For Alan the transitional space was often created through play. As Sarah wrote:

In some ways, the anxiety was gone by now and things were just at the center, which for Alan was such a playful place. I'm not sure people are used to hearing such rawness described in a way that is both simple and deeply human-connecting. He was funny, that one. And he helped bring the love and the fun out in all of us. […]

In February after 10+ inches of snow, we went outside and made wheelchair wheelies and looked at tracks into the snow.

Doing the work

Taking in the new reality of mortality and the reality of each accumulating loss—loss of hopes and ambitions, loss of physical functions, capacities, roles, and relationships—is extraordinarily hard psychological work. The work is to understand, give expression to, and play out the new reality of what is or is no longer and how it all fits in a larger scheme of things. This can also be seen as akin to the process of practicing and returning to tenderness that Mahler described as part of psychological differentiation.

Existential maturity is the state that corresponds to the external tasks of a dying person and caring for a dying person.31 In the same way that the tasks of, say, adolescence include making space for oneself in the world by getting out into it and creating or acting in their own ways, there are specific tasks for the dying. They include practical preparations, settling relationships, coming to terms with the limitations that come with declining capacity, and so on.32 We think that these tasks are both triggers for existential maturity development and facilitated by existential maturity. In turn, the work can consolidate the integrated nature of the state. For instance, making a will may trigger and then consolidate some of its development, and having some existential maturity may make it easier to make a will.

Joan and Erik Erikson, Robert Butler and Kohut all noted that people facing aging and dying have a great need for synthesis and continuity.14,33,34 People facing their own immanent death often dream or vividly daydream that dead loved ones are visiting them. People recently bereaved often dream that their lost person is so palpably present that they are shaken to find no one actually there. During mourning periods, many traditions encourage telling stories that involve the person who died so that memories become shared narrative and create continuity that way. Investment in others of things of value that had to do with the person who died is part of that continuity too, whether by giving things or passing on roles.

Continuity is aided by the kinds of transitional space already noted. Importantly, creation of small but inspiring moments by the person dying creates transitional spaces not only for the person but also for those losing him or her. Memory of them can create continuity.

Alan inspired those around them in a way that allowed them to realize death, feel it terribly, and yet move forward with a sense of loving life. We can see that Alan provided continuity for his close friend from an excerpt from the eulogy Matt gave at his funeral:

I will not forget these last months either, however unpleasant, because they say so much about who [Alan] was, what he valued, and how he lived his life. He fought with determination, but knew when to let go. He was brave not because he wasn't afraid but precisely because he was, and chose to fight hard anyway, chose to approach his battle with eyes wide open. In some of his very last words to his people, Moses instructs: “See, I have placed before you today the life and the good, the death and the evil… and you shall choose life.” And so he did.

He was never bitter, despite plenty of reason to be. He said the things that needed saying. He remained gracious and funny to the last, finding humor even in what he knew awaited. When he first decided to end his chemotherapy, he related how the doctors explained he would sleep more and more until there was nothing but. I muttered a line from a Catullus poem that somehow found its way to my throat, nox est perpetua una dormienda, “night is one eternal sleeping” but immediately stopped to correct myself—what I wanted to say was that we don't accept that the soul's life is bound up in the body's…

But Alan interrupted me: “You're right,” he said. “It's not one eternal sleeping. There's always getting up to pee.”

When we say we will think of you [Alan] always, draw inspiration from you always, love you always, we know that always is not limited by time, always is not bound up in the frailties of human breath.

When the process does not complete

Degree and timing are important. Sudden immersion in the tasks of dying could be overwhelming and traumatic. Just as a child with a nonfunctioning parent may take on some parenting roles because its the best available option but it carries costs because the child was not prepared, so too a person facing mortality may be more or less well prepared. A person without adequate prior or current processing or support may not have enough existential maturity and so may have to cope without it, and that person may be traumatized by the mismatched timing as well.

Some people for whom facing mortality is too difficult may choose instead to use death denial as a coping mechanism; we think these people might attain aspects of existential maturity but are less likely to attain it fully. We also recognize that everyone is probably this person some of the time and it is important that people find their own readiness if possible. Forced development tends to go poorly.

A characteristic feature of facing mortality through predictably progressive illness is that physical and sometimes cognitive and emotional or relational capacities are lost. So the development occurs in the face of increasing loss for the ill person. For some, the losses hasten existential maturity; for others, the losses hamper it.

People with substantial existential maturity are less likely to experience mortality—their own or a loved one's—as traumatizing, we think. Similarly, we hypothesize that grief and bereavement after the patient has died are less likely to be complicated, stuck, or melancholic if a person has existential maturity. If existential maturity is underdeveloped, death is likely to be traumatic for the dying person and/or for the bereaved. For those who do not have the time or the psychological or relational wherewithal, they will cope with whatever skills they have used for the rest of their lives. Those accompanying people facing their own or their loved one's mortality must support whatever is there and supplement with what they can. In the end, we all die as best we can.

What Emerges

In the foregoing, we described how it seems to happen and what it takes to develop existential maturity. It is also important to understand what results. What does someone with existential maturity have?

Resolving death anxiety, the death drive, fear of disintegration

The psychologists Freud, Klein, and Becker each discuss anxiety around death and how that affects people. Freud hypothesized the existence of a death instinct as a drive toward the inorganic state of not life; a kind of closing down of life, a submission to inorganic chaos that returns in the absence of eros or vitality.22 Later in his works, he argued that perhaps the same instinct projected outward is the aggression toward others that history documents in every era among groups and in territorial contests.35 Klein's delineation of the oscillation between states of apoplexy and serenity drew on this notion. Ernst Becker argued that death anxiety is so fundamental and driving that everything in life can be seen as an effort to soften the reality of death.41 Self-psychologists talk more in terms of fear of disintegration.

We see all these theories as compatible with what we observed. The process of accepting mortality both entails motivation to act in life-cycle fitting ways—creating or finalizing a material or relational legacy through teaching, reaching closure, making a will, etc.—as might fit with Becker's way of thinking—and involves moving back and forth from fearsome to embracing states as Klein and as Winnicott and others have variously described. Perhaps Freud's notion that the externally projected death instinct is the drive to destructive aggression corresponds to what we see among people facing mortality who “rage, rage against the dying of the light.”36

Kubler-Ross was the one to describe how, for many, there is a transition from aggressive pursuit of curative intervention to acceptance of death's inevitability and the body's closing down. This happened to Alan. We see this as a yielding of the fighting spirit to the internal facing death instinct in a manner that feels as fitting as every other major developmental achievement to the acceptance of death.

As Sarah wrote on behalf of the two of them to their loved ones and wider circle:

Thus it is with love and sadness that I share the news that Alan feels it is time for his body to rest. The new chemotherapy had intensified fatigue and vomiting. It was too much. Since he stopped, Alan has been able to relax into a tiredness that is more peaceful. We have started to bring the intimate circle close, working to let his and our own senses guide us.

Some days later Sarah wrote again on line for their community and loved ones:

The past few days have been delightful. Really.

Our modes have morphed over the last month: We went into crisis with the sudden change to hospice, then crash managed a new reality, then hovered in a suspended state where everything-must-be-important-because-what-if-this-is-the-last-[fillintheblank]. That was exhausting, obviously unsustainable, and—with reflection—largely self-imposed.

So, to say it again: the last few days have been delightful. Fun. Filled with only-the-punchline jokes. We're on our fifth new book (we recommend ‘The Little Prince’ and ‘Phantom Tollbooth’ to those like us who amazingly haven't yet read them). Visits are shorter and fewer; we're staking claim to a sense of home (as of last month we celebrated one full year of actually living together). A new doc visited, tweaking meds and fluids which built strength and cut vomiting in half. (To be fair, he still needs the wheelchair to get from couch to bed at nighttime and vomits two or three times a day which may seem like a lot to you but feels fantastic from here.)

Now seems as good as ever to share something Alan said to a friend back in the fall:

- The friend asked for Alan's advice.

- Alan posed back the question: “Are you buoyant with how you spend your time?”

Buoyant. I love it. I've been thinking about that perhaps slightly misplaced but fabulously vibrant word ever since.

Love and spiritual comfort

Existential maturity is an achievement beyond other major developmental achievements. The continuity that people seek is with those who have died. The serenity that they find is by having a sense of place in relation to the universe. Serenity for most entails having comfort with what that place is. For some, it is concrete and explained in terms of the transformation from living to lifeless material—the body dies and decays. For others, it is a sense of participation in the greater forces of life in which our mortal life is just one part. For some, its mystery is of great consequence—negative or positive. For others, it seems acceptable that human understanding is insufficient. For some, it is spiritual in the sense of feeling awe and smallness within grandeur, something some atheists and humanists emphasize. For others, it is religious.37 But people, each in their own way, seek some way to come to terms with place and continuity in the larger universe.38

Access to and integration of a way to feel part of, connected to, or comfortable with our place in the universe are a principal feature of existential maturity. For many this state has a lot to do with love. Sometimes it is much focused on love between the dying person and a primary other, as for Sarah and Alan. Sometimes it is a different kind of love—between the dying person and other relatives, friends or colleagues, or professional caregivers. It can also be a love between a person and the internal representation of someone deceased. Often it is a combination.

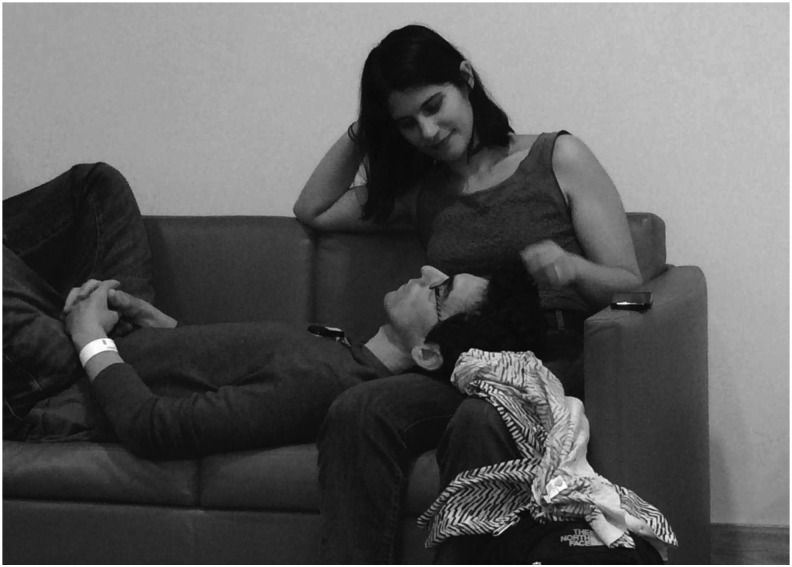

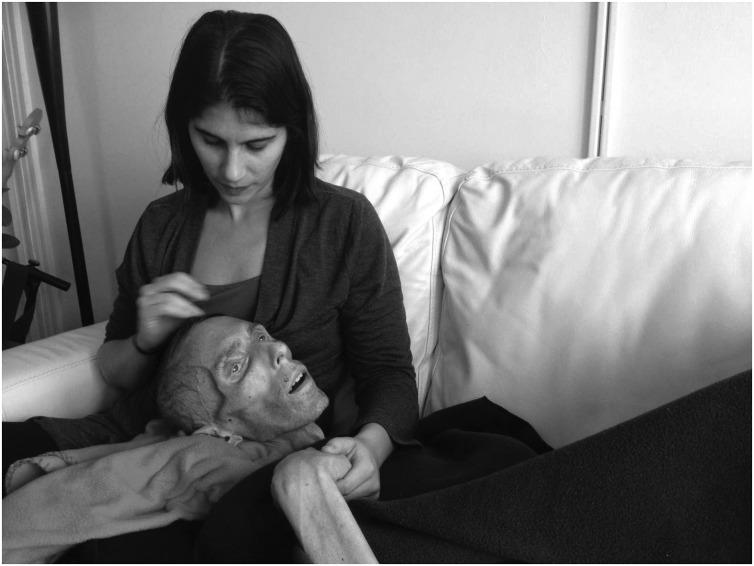

Sarah captured how this effort happened and happened again and again through their journey, shared together and with others. Alan did not describe himself as spiritual, but others saw him as spiritual (his hospice doctor said, talking of how she thought about his prognosis; “when he opened his mouth and talked, there was a spiritual strength and some sort of resilience and not-willingness to die that made me clearly understand that he has much more time to live.”) and he was observant of ritual—he did feel that “it matters how one does things.” Alan's spirituality came through in his love, his humor, and his forthright living. Sarah captured a moment that seems filled with love and down-to-earth spirituality (Figs. 1 and 2):

FIG. 1.

Alan and Sarah in waiting room before his first treatment. (This photo is not covered by the CC-BY-NC license and may not be re-used in any form.)

FIG. 2.

Alan and Sarah at home. (This photo is not covered by the CC-BY-NC license and may not be re-used in any form.)

July 2014

Alan and I were awaiting his first treatment. As he rested, I met eyes with a fellow [patient] across the way who silently asked if she could take a photo. She told me later that being loved and touched was so important and that she was glad to see us together. I was so moved by her gesture, especially as it turned out she herself was returning for her first bout of post-remission treatment. We texted throughout the day:

To: Thank you for noticing and capturing that sweet moment. Your friend gave us your number. I'm glad since I wanted to say you have such a lovely smile. My name is Sarah and my husband is Alan. He will be having his first treatment this morning. We wish you much health and comfort in yours.

From: first day of treatment is scary because you don't know what to expect, so just be strong, rub him, and be sure to keep him hydrated these next few days! [heart symbol]

To: How kind of you—scary is exactly how he says it feels. Thanks for sharing your wisdom (:

From: it's my first time getting chemo today since fall of 2013 so i fully understand:) it gets simpler and you feel better sooner (i have breast cancer so the pain is severe and constant, chemo helps stop it in its tracks!).

July 2014

From: hi, this is the mother of the young lady that took the pic of you and your husband. she passed away this summer. she lost her battle. I just wanted to know how he was doing? she thought of ya'll a lot. i miss her a lot.

From: i was there that day. i gave you the number. i'm just looking through her phone.

To: Oh, I'm so sorry to hear of your loss. Your daughter was so special to us and gave us a huge gift that day in her noticing us and sharing the photo. That was our first day at Dana Farber and he ended up being admitted to the hospital that day instead of starting chemo. Subsequently he has been doing much better but wow it is tough. Your daughter was young, too, I think I remember.

To: She brought a moment of love and joy to our life as I'm sure she did to yours and so many others. I wish you much comfort and may her memory be for a blessing.

February 2015

A friend recently sent Fig. 2. We now have continuous support to make sure that Alan is comfortable and feels surrounded by love. We have been learning a lot from the nurses about how to provide this. Just now, the nurse said: “Put your hand here, on his forehead. He likes it there.”

Each of these moments was seen by another—the first taken by a fellow patient they had never before met and would never meet again who was sitting across a waiting room, the second taken by a close friend visiting them in their home—and given to them as a gift.

The reader may ponder the photograph of Alan being held gently by Sarah when he was so close to death. Perhaps it is alarming. Perhaps it invokes envy. Perhaps it invokes awe. Sarah described her own different reactions. When she first received the picture, she recalled the experience of sitting together with Alan in a moment of tenderness and calm. Months later, a friend admitted being deeply disturbed. Sarah looked again and was suddenly scared: “I hadn't seen it before. The face was so hollow. That's not what I saw then, and it's not what I remember.” One relative willfully tried to put aside the pain of a seeing a body dying while holding onto the evidence of a loved one being embraced. Whatever is seen, these images show real moments inside a relationship, witnessed by others and seen as worthy of a gift.

Existential maturity unfolds in life, in relationships, in homes and in hospitals, in whatever situations we find ourselves. Journeying to death is the closest we living get to the end of life. It can feel enormous and ultimately intimate. Awareness of our mortality activates a powerful need to relate to what is larger than our life. Existential maturity places no frame on what kind of way a person finds to being at ease with his or her place in the grand scheme. A common adage is that the worst way to die is alone. But at the same time sometimes the dying say it's hard to die in the company of loved ones. People who find oneness with the universe may seek whatever relationship works for them – in their spiritual practice, in nature, with a person, or however. For many people, dying in the company of loved ones is the way both the dying and the living find a connection that carries them. However it is done, finding a way does seem to be part of the successful work of achieving existential maturity.

Psychological structures of existential maturity and existing theoretical constructs of the mind

Our inner selves and ways of relating can be thought of as having structure, that is, the pathways of thinking and feeling and relating that make up our nature. Earlier we describe processes that create structure and what results; processes that adjust our ways of thinking and feeling and relating and how we are changed by that. We are aware that our next task is to discern how the structures of existential maturity, or their lack or misdirection, are explained within the major models that exist in psychodynamic theory. Models we note at the outset include classical and ego psychology, self-psychology, object relations, developmental and attachment theory, as well as neuropsychoanalytic and neuropsychological theory. These constructs coexist in a ne'er too easily reconciled manner among psychodynamic psychologists; some adhere to one model, whereas others seek to synthesize them.42 However, each has strong explanatory power and clinical utility. Therefore, we see our next job is to show how existential maturity fits with each one. This, along with a visual model for existential maturity, is intended for a forthcoming article.

Implications for Palliative Care Professionals

This notion that existential maturity is a developmental state has implications for clinicians and others who seek to help. It may be particularly distinct from, although not entirely incompatible with, some of the prevailing conceptions of the place of death in life that analysts have espoused in which death anxiety is a negative force to acknowledge and work with but not integrate as a positive possibility.39,40 We see our notion as consistent with more recent psychoanalytic approaches.15,16 Our model suggests that the best way to help is the same as for other forms of sometimes difficult development that occur in the usual course of life. Presence, understanding, listening, and appreciating, as well as role modeling, awareness of how the process can go awry, and thoughtfully tailored suggestion or guidance, provide the most powerful psychological milieu for developing any innate state. We think this is true for developing what it takes to face mortality. For some, there are enough resources and capacity without professional help; for many, professional assistance is critical.

So if existential maturity is an innate capacity, developed or not developed just like other stages, it will not lend itself well to being learned only cognitively or by adopting behaviors unless these aspects are connected to affective experience and worked through within the individual and in relationship. That means that protocol-based or other formulaic interventions will likely be effective only if they incorporate the person's own experience, needs, and relationships. Both the leading interventions currently rendered in stepwise procedures do allow extensively for the person's unique narrative, needs, and relationships.7,8

People who have serious illness often have declining cognitive and physical capacity and perhaps not a lot of time, which may make things complicated. Our impression is that existential maturity may emerge surprisingly rapidly and against the odds. But it does not always, and perhaps when it does, there was some prior development in a latent form. Given the importance of existential maturity to quality of dying and quality of bereavement and recovery, people may wish to consider how a culture of death awareness and optimal exposure through multigenerational living and inclusion of illness care in normal life could foster the development of existential maturity for many in our society. Providers of care who have themselves developed existential maturity will be able to offer a steadier, wiser containing relationship in which a dying person and his or her loved ones can develop theirs. Palliative care providers should be clear about their own relationship to mortality and how it impacts their provision of care.

This model offers a way to understand where the person facing death is psychologically and how to support and foster their well-being. This thinking through involves making hypotheses and testing them by offering something fitting, then adjusting depending on what emerges. Researchers too should be able to use the model to generate hypotheses and potentially from there new approaches or new studies that, in turn, may modify the model.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Emanuel LL, von Gunten CF, Ferris FD, Hauser J. (eds): The Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care (EPEC) Curriculum: © The EPEC Program, 1999–2011. “Plenary 3: Elements and models of end-of-life care; Cicely Saunders trigger tape.” http://bioethics.northwestern.edu/programs/epec/ (Last accessed November20, 2016)

- 2.Kubler-Ross E: On Death and Dying. New York: MacMillan, 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland JC, Breitbart WS, Jacobsen PB, et al. :. Psycho-Oncology, 3rd Edition Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN: 9780199363315 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark D: ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of cicely Saunders, 1958–1967. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, et al. : Measuring quality of life at the end of life: Validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Clipp EC, et al. : ‘Are you at peace?’: One item to probe spiritual concerns at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:101–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chochinov HM: Dignity Therapy. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Applebaum AJ, Kulikowski JR, Breitbart W: Meaning-centered psychotherapy for cancer caregivers (MCP-C): Rationale and overview. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:1631–1641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson VA, Jacobsen J, Greer JA, et al. : The cultivation of prognostic awareness through the provision of early palliative care in the ambulatory setting: A communication guide. J Palliat Med 2013;16:894–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emanuel L, Scandrett KG: Decisions at the end of life: Have we come of age? BMC Med 2010;8:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed ML: A Bibliography of William Wordsworth 1787–1930. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopkins J: Living under the threat of death: The impact of a congenital Illness on an eight-year-old boy. J Child Psychother 1977;4:5–21 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freud S: Three essays on the theory of sexuality. In: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume VII (1901–1905): Chapter II: Infantile Sexuality. London, Hogarth Press; 1905 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erikson EH: The Life Cycle Completed. London: W.W. Norton &.Co, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Straker N. (ed): Facing Cancer and the Fear of Death: A Psychoanalytic Perspective on Treatment. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slavin MO: Lullaby on the dark side: Existential anxiety, making meaning and the dialectic of self and other. In: Aron L, Harris A. (ed): Relational Psychoanalysis. Vol. 4 New York: Routledge, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shedler J: The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. Am Psychol 2010;65:98–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winnicott DW: The use of an object. Int J Psychoanal 1969;50:711–716 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowlby J: A Secure Base: Parent-child Attachment and Healthy Human Development. New York: Basic, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlow HF, Dodsworth RO, Harlow MK: Total social isolation in monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1965;54:90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buber M: I and Thou. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freud S: Beyond the pleasure principle. In: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVIII (1920–1922). London, Hogarth Press, 1920, pp 14–17 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bion WR: The psycho-analytic study of thinking. II. A theory of thinking. Int J Psychoanal 1962;43:306–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freud S. Mourning and melancholia. In: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914–1916). London, Hogarth Press; 1917 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kohut H: In: Goldberg A. (ed): How Does Analysis Cure? Chicago: University of Chicago, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balint M: The Basic Fault: Therapeutic Aspects of Regression. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothenberg A, Hausman CR: The Creativity Question. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laing RD: The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise. London, Penguin, 1984, p. 137 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohut H: The Analysis of the Self; a Systematic Approach to the Psychoanalytic Treatment of Narcissistic Personality Disorders. New York: International Universities, 1971 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahler MS: A study of the separation-individuation process: And its possible application to borderline phenomena in the psychoanalytic situation. Psychoanal Study Child 1971;26:403–424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knight SJ, Emanuel L: Processes of adjustment to end-of-life losses: A reintegration model. J Palliat Med 2007;10:1190–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emanuel L, Bennett K, Richardson VE: The dying role. J Palliat Med 2007;10:159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Erikson JM: In: Erikson EH. (ed): The Life Cycle Completed. Extended Version with New Chapters on the Ninth Stage of Development by Joan M. Erikson. New York: W.W. Norton, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butler RN: The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry 1963;26:65–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freud S: Civilization and its Discontents. In: The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XXI (1927–1931). London, Hogarth Press; 1930 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas D: Do not go gentle into that good night. In: Country Sleep: And Other Poems. New York: James Laughlin, 1952 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pargament KI: Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy: Understanding and Addressing the Sacred. New York: Guilford, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emanuel L, Handzo G, Grant G, et al. : Workings of the human spirit in palliative care situations: A consensus model from the chaplaincy research consortium. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker E: The Denial of Death. New York: Free, 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski TA: The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life. New York: Random House, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Becker E: The Denial of Death. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1973 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilson A, Gedo JE: Hierarchical Concepts in Psychoanalysis. New York: Guilford Press, 1992 [Google Scholar]