Abstract

Background: The optimum therapy for Graves' disease (GD) is chosen following discussion between physician and patient regarding benefits, drawbacks, potential side effects, and logistics of the various treatment options, and it takes into account patient values and preferences. This cohort study aimed to provide useful information for this discussion regarding the usage, efficacy, and adverse-effect profile of radioactive iodine (RAI), antithyroid drugs (ATDs), and thyroidectomy in a tertiary healthcare facility.

Methods: The cohort included consecutive adults diagnosed with GD from January 2002 to December 2008, who had complete follow-up after treatment at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Data on treatment modalities, disease relapses, and adverse effects were extracted manually and electronically from the electronic medical records. Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed to evaluate the association of treatments with relapse-free survival.

Results: The cohort included 720 patients with a mean age of 49.3 years followed for a mean of 3.3 years. Of these, 76.7% were women and 17.1% were smokers. The initial therapy was RAI in 75.4%, ATDs in 16.4%, and thyroidectomy in 2.6%, while 5.6% opted for observation. For the duration of follow-up, ATDs had an overall failure rate of 48.3% compared with 8% for RAI (hazard ratio = 7.6; p < 0.0001). Surgery had a 100% success rate; 80% of observed patients ultimately required therapy. Adverse effects developed in 43 (17.3%) patients treated with ATDs, most commonly dysgeusia (4.4%), rash (2.8%), nausea/gastric distress (2.4%), pruritus (1.6%), and urticaria (1.2%). Eight patients treated with RAI experienced radiation thyroiditis (1.2%). Thyroidectomy resulted in one (2.9%) hematoma and one (2.85%) superior laryngeal nerve damage, with no permanent hypocalcemia.

Conclusions: RAI was the most commonly used modality within the cohort and demonstrated the best efficacy and safety profile. Surgery was also very effective and relatively safe in the hands of experienced surgeons. While ATDs allow preservation of thyroid function, a high relapse rate combined with a significant adverse-effect profile was documented. These data can inform discussion between physician and patient regarding choice of therapy for GD.

Keywords: : Graves' disease, hyperthyroidism, antithyroid drugs (ATDs), radioactive iodine (RAI), thyroidectomy, comparative effectiveness

Introduction

Graves' disease (GD) is the most common form of hyperthyroidism in the United States (1). Standard management options for overt hyperthyroidism include antithyroid drugs (ATDs), radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy, and thyroidectomy, although some patients with mild or subclinical disease may elect to be monitored or use beta-blockers alone (2). Despite the use of these three treatments for decades, selection of the optimal therapy for GD still poses a challenge for both the physician and the patient. Each therapy has its unique advantages and disadvantages, and there is no single best therapy for all patients. A prudent approach is to make a selection after a thoughtful discussion with the patient regarding advantages, risks, and cost-effectiveness, taking into consideration the values and preferences of the patient.

The goal of this study was to determine the effectiveness of ATDs compared to the definitive treatment options (RAI and surgery) in a historical cohort of patients at a tertiary referral center in the United States. In addition, the study determined whether there were any changes in treatment preference within a group of physicians over the time of the study. This information will strengthen the current evidence and will be a useful resource for physicians to involve patients in the shared decision-making process.

Methods

Overview and study design

A historical single-cohort study was conducted involving adults diagnosed and treated for Graves' hyperthyroidism between January 1, 2002, and December 31, 2008, at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. The effectiveness and adverse effects of treatment with ATDs, RAI, and surgery were evaluated, as well as the change in trend of practice over the time of the study.

Setting and participants

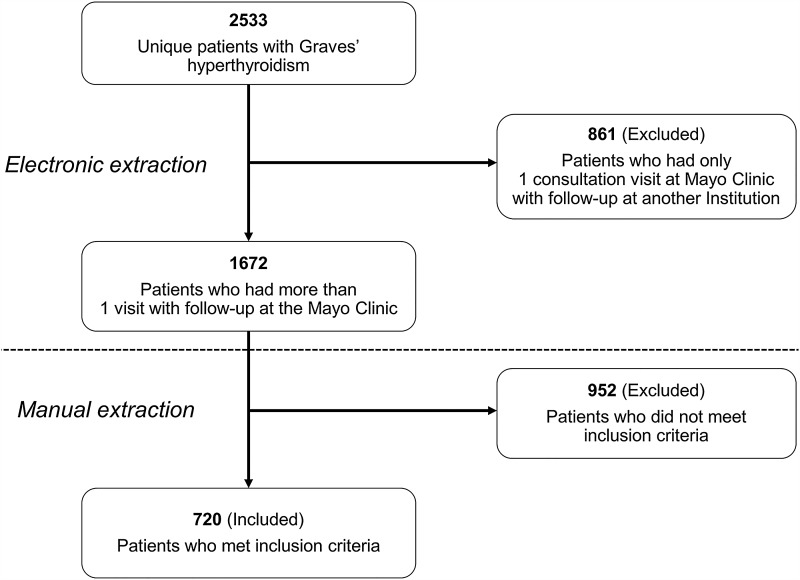

The electronic medical records of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, were reviewed to identify all patients with GD who were diagnosed and treated at the institution between January 1, 2002 and December 31, 2008. As the Mayo Clinic is a tertiary referral center, patients included in this study originated from various geographic locations, both within and outside the United States. The validated Data Discovery and Query Builder (DDQB v2.1; IBM Corp.) was utilized to build the initial cohort and to extract the data (3). From 2533 unique patients diagnosed with GD, 861 were excluded, since they had a single visit to the institution (Fig. 1). A single investigator (V.S.) then identified the final cohort of 720 patients meeting all the following inclusion criteria: adult patient (aged ≥18 years), new diagnosis of GD, first treatment evaluation performed at the Mayo Clinic, and at least one follow-up visit at the Mayo Clinic after the completion of therapy. Patients who were treated with ATDs for two months or less prior to presenting to the Mayo Clinic were also included. Women who were pregnant or lactating were excluded, as they are not candidates for RAI therapy. Demographic information (age at diagnosis, sex, race/ethnicity, and zip code) and laboratory data (thyroid function tests and thyrotropin receptor antibody titer [TRAb]) were extracted electronically using the DDQB, while other clinical variables were collected manually.

FIG. 1.

Cohort selection.

Patients were treated with ATDs, RAI, or thyroidectomy, or were monitored with or without beta-blockers. Methimazole (MMI) or propylthiouracil (PTU) were the ATDs used on a titration regimen to achieve a euthyroid state. Block and replace therapy was not used. RAI therapy was given as a single oral dose of 131I labeled sodium iodide (Na 131-I) in liquid or capsule form. The treatment dose was calculated using the formula: [gland size (g) × 200 μCi/g × 100]/% uptake at 24 h (4). The surgical procedure was either a total or near total thyroidectomy. A small fraction of the patients with mild disease were treated with beta-blockers, at least initially, and monitored with regular follow-up visits.

Outcomes

Treatment failure was defined as continued hyperthyroidism, despite a maximum tolerable dose of ATDs; adverse effects necessitating a change in ATD to a different therapy (RAI or thyroidectomy); recurrence of hyperthyroidism after attaining remission; or persistence of biochemical hyperthyroidism six months after a dose of RAI or following thyroidectomy. If none of these criteria was met, the treatment was considered successful. Remission was defined as being euthyroid for 12 months after stopping ATD therapy. Some patients changed to an alternate ATD due to minor side effects and some to a definitive therapy based on personal preferences. Since it was not possible to categorize the initial ATD therapy as a failure or success, it was excluded from the analysis.

Adverse effects of ATDs, including gastrointestinal (nausea, gastric distress, dysgeusia, dysosmia, sialadenitis), cutaneous (pruritus, macular rash, urticaria), and rheumatological (arthralgia, polyarthritis, ANCA-positive vasculitis), were obtained from the clinical notes, as documented by the treating physician. Hematological adverse effects were confirmed using the following criteria: agranulocytosis—absolute granulocyte count <500/μL (5); thrombocytopenia—platelet count <150,000/μL (6); and aplastic anemia—pancytopenia with bone-marrow hypocellularity (7). Hepatic adverse effects were confirmed as follows: hepatocellular—aminotransferases >3 upper limit of normal (ULN); and cholestatic—alkaline phosphatase >3 ULN.

Radiation thyroiditis was defined as pain and tenderness over the thyroid gland 5–10 days after RAI therapy, as documented by the physician. Postsurgical complications (bleeding/hematoma, laryngeal nerve injury, and hypoparathyroidism) were collected from clinic notes, as documented by the surgeon/physician.

To test the reliability of the data extraction, a second investigator re-abstracted 10% (72 patients) of randomly selected patients from the cohort that had been previously abstracted. Based on the number of abstraction differences between the two investigators, the data extraction process (electronic and manual) was determined to be 98.7% reliable.

Ethical approval

Patients were followed in the study for the whole period of care at the Mayo Clinic, as documented in the electronic medical records. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the protocol without the need for informed consent. Records of patients who had not given prior authorization to have their medical records reviewed for research purposes were excluded in compliance with Minnesota State Law. The authors have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical Publishing (8).

Statistical analysis

Group statistics for the continuous variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and range, depending on the normalcy of the distribution. Categorical variables are summarized as percentages. Comparison between groups was based on a two-sample t-test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi square test for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier analyses are represented as time-to-failure plots. Univariate and multivariate analyses to identify potential predictors of failure were performed with the logistic regression model using SAS software v9.2. Results of these analyses are summarized as odds ratios (OR), confidence intervals (CI), and p-values. p-Values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant and are reported with three digits if p < 0.1.

Results

Choice of therapy

The cohort initially consisted of 2533 unique patients diagnosed with GD, from which 1813 were excluded, since they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Among the 720 patients included, 22 were already on ATD therapy initiated by the referring providers within two months of their initial visit to the Mayo Clinic. Hence, only 698 patients had their first-line therapy initiated at the Mayo Clinic.

The mean age of participants was 49.3 years, with a mean follow-up duration of 3.3 years. There were 76.7% women, and 17.1% were smokers. Baseline characteristics are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of the Cohort

| Variable | ATD 118 (16.4%) | RAI 543 (75.4%) | Surgery 19 (2.6%) | Observation 40 (5.6%) | Total 720 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 47.8 (14.5) | 49.4 (14.8) | 44.9 (14.8) | 53.8 (15.8) | 49.3 (14.9) |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| <40 | 34 (17.8) | 142 (74.3) | 8 (4.2) | 7 (3.7) | 191 (26.5) |

| 40–60 | 59 (15.9) | 283 (76.7) | 8 (2.2) | 19 (5.1) | 369 (51.3) |

| >60 | 25 (15.6) | 118 (73.75) | 3 (1.9) | 14 (8.75) | 160 (22.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 93 (16.8) | 413 (74.8) | 15 (2.7) | 31 (5.6) | 552 (76.7) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 11 (8.9) | 101 (82.1) | 7 (5.7) | 4 (3.25) | 123 (17.08) |

| Goiter size, n (%) | |||||

| <20 g | 19 (23.75) | 46 (57.5) | 0 | 15 (18.75) | 80 (11.1) |

| 20–50 g | 92 (15.7) | 454 (77.6) | 14 (2.4) | 25 (4.3) | 585 (81.3) |

| >50 g | 5 (15.6) | 25 (78.1) | 2 (6.3) | 0 | 32 (4.4) |

| Orbitopathy, n (%) | 16 (21.62) | 49 (66.21) | 4 (5.40) | 5 (6.75) | 74 (10.3) |

| fT4, M (SD) | 3.2 (1.9) | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.9) | 1.8 (0.8) | 3.4 (2.1) |

| fT3,aM (SD) | 7.3 (4.3) | 8.0 (4.7) | 8.1 (6.2) | 4.3 (1.0) | 7.7 (4.6) |

| TT3,aM (SD) | 298.7 (191.2) | 345.4 (200.1) | 265.3 (103.5) | 174.0 (53.6) | 319.7 (194.0) |

| TRAb, n (%)a | |||||

| Absent (<10% inhibition) | 5 (23.8) | 13 (61.9) | 0 | 3 (14.3) | 21 (6.6) |

| Indeterminate (10–14%) | 6 (22.2) | 13 (48.1) | 2 (7.4) | 6 (22.2) | 27 (8.5) |

| Positive (≥15%) | 51 (18.9) | 204 (75.6) | 7 (2.6) | 8 (2.9) | 270 (84.9) |

| 24 h RAI uptake, M (SD) | 48.9 (21.1) | 52.2 (18.9) | 46.6 (26.9) | 33.4 (11.8) | 50.7 (19.5) |

| Mean follow-up, years (SD) | 1.5 (2.2) | 3.8 (3) | 4.3 (3.1) | 2.5 (2.6) | 3.3 (3) |

Date available in ≤80%.

ATD, antithyroid drugs; RAI, radioactive iodine; fT4, free thyroxine; fT3, free triiodothyronine; TT3, total triiodothyronine; TRAb, thyrotropin receptor antibody.

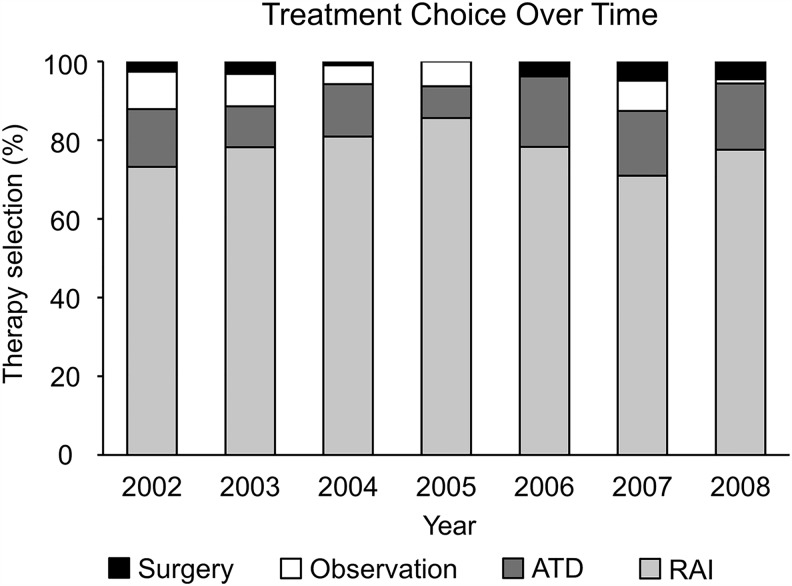

The most commonly used therapy was RAI, followed by ATDs, and surgery. There was no significant change over time in the relative proportions of patients who received each treatment modality (Fig. 2). Additionally, no sex-specific differences in choice of therapy were identified either: 74.8% (413/552) of women were treated with RAI and 16.8% (93/552) received ATD therapy compared with 77.4% (130/168) and 14% (25/168) of men receiving RAI and ATDs, respectively. Surgery was chosen by 2.7% (15/552) of women and 2.4% (4/168) of men, and observation without initial treatment in 5.6% (31/552) of women and 5.4% (9/168) of men.

FIG. 2.

Treatment choice over time.

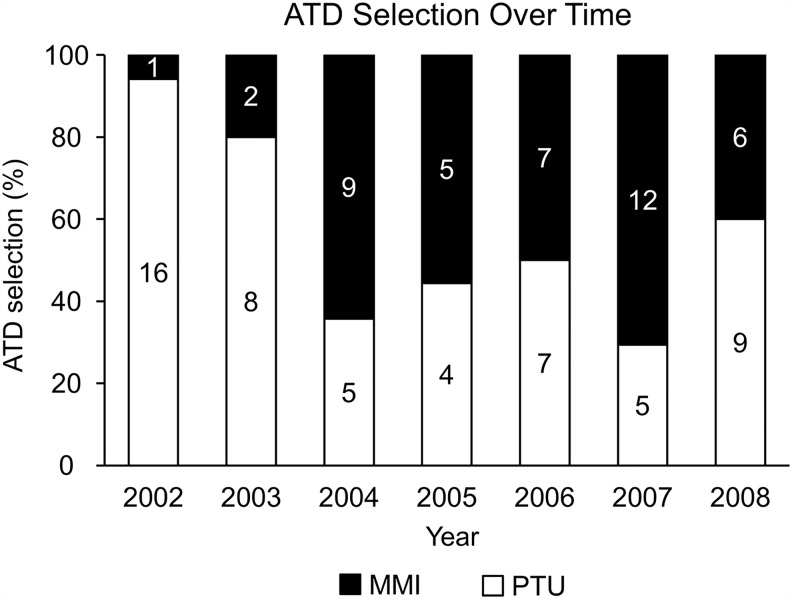

A trend was found for an increasing use of MMI and decreasing use of PTU after 2003 (Fig. 3). The choice of therapy based on the geographic location of the patient was also evaluated (Table 2). Overall, RAI was the preferred therapy for patients from all locations.

FIG. 3.

Antithyroid drug (ATD) selection over time.

Table 2.

Preference of Therapy Based on Geographic Location of Patients

| Geographic location | ATD | RAI | Surgery | Observation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwesta | 93 | 490 | 16 | 39 | 638 |

| Other 44 states | 3 | 48 | 2 | 1 | 54 |

| Outside the United States | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 96b | 543 | 19 | 40 | 698b |

Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Michigan.

Twenty-two patients were initiated on ATDs by their physicians outside the Mayo Clinic and hence excluded: 118 – 22 = 96 and 720 – 22 = 698.

Treatment failure rates and prediction of failure

First-line therapy

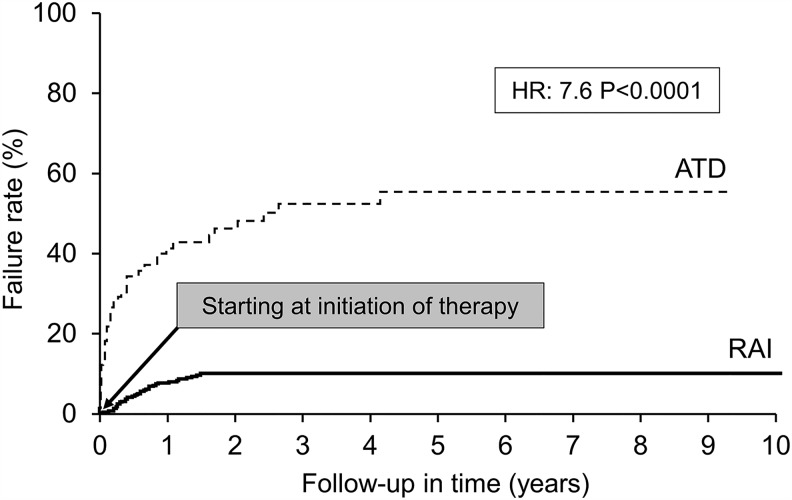

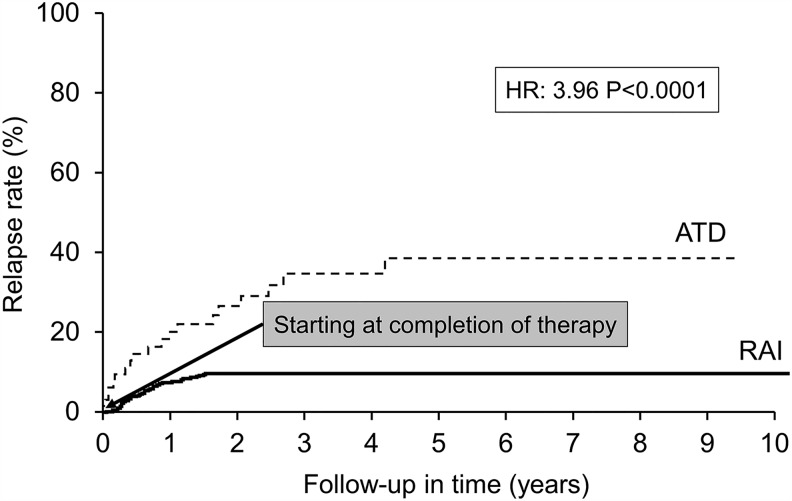

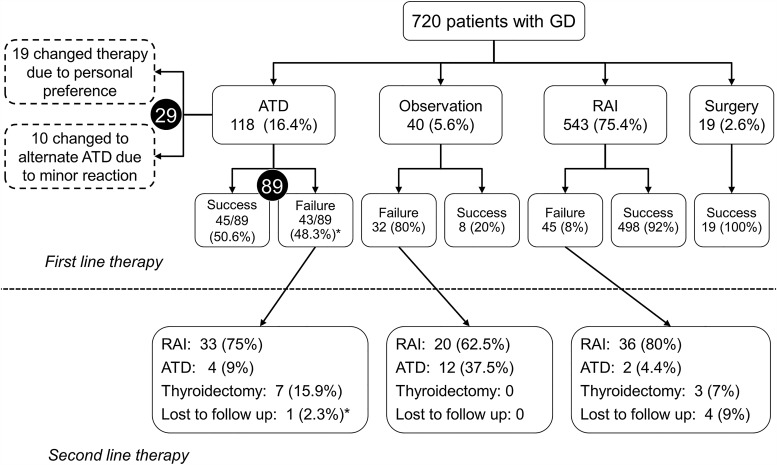

ATDs had an overall failure rate of 48.3% compared with 8% for RAI (hazard ratio [HR] = 7.6; p < 0.0001) for the duration of follow-up (Fig. 4). Among the 118 patients who were treated with ATDs, 29 changed therapy due to personal preferences, and 10 changed to a different ATD due to a minor adverse effect. Among the remaining 89 patients, 25 were considered failures due to premature cessation of ATDs for two reasons: (i) persistent hyperthyroidism on maximal dose of ATD, and (ii) adverse effect necessitating a change to RAI or surgery. Sixty-four patients completed long-term therapy (>12 months) to attain remission, and 17 (27.4%) among them suffered a relapse (HR = 3.96; p < 0.0001; Fig. 5). No patient who underwent thyroidectomy had recurrent hyperthyroidism. Eighty percent of the 40 patients with mild or subclinical hyperthyroidism, who were initially observed, worsened during follow-up and were treated with either RAI or ATDs. The therapies opted for by patients who failed first-line therapies are represented in Figure 6.

FIG. 4.

ATD versus radioactive iodine (RAI)—failure.

FIG. 5.

ATD versus RAI—relapse.

FIG. 6.

Treatment selection (success vs. failure).

Second-line therapy

A total of 101 patients opted for RAI after relapse following previous RAI or other treatment. In this group, 84 (83.2%) patients experienced a successful result while 11 (10.9%) failed treatment, and 6 (5.9%) were lost to follow-up. The most commonly chosen therapy for those failing RAI therapy was another dose of RAI (81.8%; 9/11).

Among the 28 patients treated with ATDs, 11 were successful, 12 failed, and five changed to a different therapy because of personal preference. Again, RAI was the most commonly chosen therapy for those who failed ATDs (75%; 8/12).

Thirteen patients underwent thyroidectomy as second-line therapy with a 100% success rate.

Third-line therapy

Nineteen patients received RAI, among whom 18 (94.7%) had a successful outcome. Among the five patients treated with ATDs, three were successful. Three patients underwent thyroidectomy with a 100% success rate.

Fourth-line therapy

Two patients were treated: one with RAI and one with ATD. Both achieved a successful outcome.

A multivariate analysis was conducted that included sex, goiter size, free thyroxine (fT4) value, and 24-hour RAI uptake to determine whether risk factors for RAI failure could be identified. After adjusting for sex, the odds for being in the failure group were found to be increased by 28% for each unit increase in the fT4 level. Similar predictive modeling for the ATD group included the variables of goiter size, smoking status, fT4, and RAI uptake; none was significant in the univariate analysis. However, the probability of failure after treatment with ATDs was significantly higher for patients with an elevated TRAb level at diagnosis (p = 0.008). No significant association was found between treatment failure and TRAb level for the RAI group. Overall TRAb titers were available in only 44% of the cohort.

Graves' orbitopathy

The cohort included 73 patients with a diagnosis of Graves' orbitopathy (GO) prior to the initiation of treatment. Their disease was recorded as mild in severity and inactive. Therapies selected for those patients were ATD (15; 20.5%), RAI (49; 67.1%), and surgery (4; 5.5%), while one patient with mild hyperthyroidism was initially observed and subsequently treated with ATD. Among the 647 patients without GO at the time of initiation of therapy, 43 (6.6%) developed GO after treatment. This included 7/647 (1%) treated with ATDs, 35/647 (5.9%) treated with RAI, and one patient who was observed. No association was found between the development of GO after RAI therapy and sex or smoking status in this cohort.

Adverse effects

ATD therapy

Forty-five adverse effects were noted secondary to ATDs in 43 patients among 248, as detailed in Table 3 (118 underwent long-term therapy and 130 were treated with ATDs for a short term in preparation for RAI or surgery). This included minor reactions of dysgeusia (4.4%), rash (2.8%), nausea/gastric distress (2.4%), pruritus (1.6%), urticaria (1.2%), arthralgia (0.4%), polyarthritis/antithyroid arthritis syndrome (0.4%), headache (0.4%), and dizziness (0.4%). Major reactions included elevated liver enzymes (2.4%), cholestasis (0.8%), and agranulocytosis (0.8%). Among the 43 patients, 34 were on long-term ATD therapy, while nine were treated for a short duration. Of the 43 patients in whom adverse effects occurred, 25 opted for a change in therapy (another ATD in 10, RAI in 10, and surgery in 5). The remainder continued on with the same ATD, while one patient was lost to follow-up.

Table 3.

Adverse Effects of Thionamides

| Adverse effects (%) | Methimazole (n = 110) | Propylthiouracil (n = 138) |

|---|---|---|

| Urticaria | 1.8 | 0.7 |

| Rash | 5.5 | 0.7 |

| Pruritus | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Arthralgia | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Gastric distress | 1.8 | 3.0 |

| Dysgeusia | 3.6 | 8.0 |

| Dizziness | 0.9 | 0 |

| Headache | 0.9 | 0 |

| Severe neutropenia | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Transaminitis | 0 | 0.7 |

| Cholestasis | 0.9 | 0 |

Sixty percent (27/45) of the adverse effects were secondary to MMI, while 40% (18/45) were attributed to PTU. The rate of adverse effects for MMI was higher at 24.5% (27/110) compared with PTU at 13% (18/138). Almost all (22/27) adverse effects on MMI occurred in patients taking ≥20 mg/day, while two events occurred at lower doses. For three patients, the dose could not be ascertained, yet the adverse effects occurred on the initiation dose (within two to five weeks of starting therapy). Nine adverse effects occurred in patients treated with ATDs outside the institution prior to referral. One was agranulocytosis due to PTU and another was MMI-related polyarthralgia.

RAI therapy

Radiation thyroiditis developed in 8/664 (1.2%) patients who underwent RAI therapy.

Thyroidectomy

A total of 35 patients underwent thyroidectomy either as first-, second-, or third-line therapy. Of these, one (2.9%) patient developed postoperative hematoma, and another one (2.9%) suffered a permanent superior laryngeal nerve injury. Ten (28.6%) patients experienced transient hypocalcemia, eight of which resolved in a mean follow-up time of two months (range 1–4 months). Two patients were still hypocalcemic at two months follow-up, but the final outcome could not be ascertained due to lack of further follow-up data.

A total of seven thyroid malignancies were diagnosed in patients who underwent thyroidectomy. Three were papillary thyroid microcarcinomas identified incidentally on postoperative surgical pathology, while the other four were diagnosed preoperatively by fine-needle aspiration cytology (three stage II and one stage III).

Discussion

This study presents the largest cohort of GD patients treated at a single institution. Their demographics were identified as being fairly consistent with the literature (9) regarding their age (51.25% aged 40–60 years, 26.5% <40 years, and 22.2%> 60 years). There was slightly less female predominance in the cohort (female:male ratio of 3.3:1) compared to other cohorts reporting a female preponderance ratio of 5–10:1 (10).

RAI was the most commonly used first-line treatment, selected by approximately 75% of the patients in the cohort, followed by ATDs and thyroidectomy. This finding was close to the 69% rate of RAI use as first-line therapy reported by U.S. endocrinologists in 1990 (11) but significantly higher than the more recent rate of 60% obtained in a similar survey (12). The high rate of RAI use in this population may be explained by the ease of treatment, high success rate, low adverse-effect profile, and decreased frequency of follow-up, particularly convenient for a population that has to travel a significant distance to reach its endocrinologist. These beneficial features may be more important to some patients and physicians than the expected inconvenience of permanent hypothyroidism requiring lifelong levothyroxine replacement. Also, the possibility of developing new GO, or worsening of preexisting GO as occurs for between 13% and 33% of patients following RAI, is a concern for some, but this seems to be less important for the majority of patients (13–15). In addition to patient values, physician comfort and experience with a particular treatment likely plays an important role in treatment selection. Interestingly, the cohort identifies a trend toward an increasing use of ATDs compared with RAI therapy from 2006 onwards. From 2006 to 2008, more patients opted for ATDs (ATD:RAI ratio of 1:4.4), which was a definite increase compared to the years 2002–2005 (ATD:RAI ratio of 1:6.8; Table 3). This trend coincides with the trend mentioned earlier (12). An additional reason why physicians might have considered ATDs more frequently may be due to a study reporting higher rates of radiation-induced malignancies related to RAI therapy (16).

Avoidance of permanent hypothyroidism, which requires lifelong levothyroxine replacement with variable impact on quality of life, continues to be a concern based on the multitude of trials testing alternative approaches (17,18). The fact that a subgroup of patients on levothyroxine replacement alone does not enjoy a good quality of life may be an important deciding factor for patients in their choice of therapy. Also, patients may be steered away from RAI by questionable information obtained from some patient-oriented Web sites. On the other hand, a follow-up study on the quality of life in GD patients 14–21 years following randomization to RAI, ATD, and surgery revealed no significant differences among the three treatment groups (19). While this was not identified in this study, it should also be mentioned that there is a group of patients who prefer long-term ATD therapy when they are not able to reach remission after 18 months. The safety of this approach has been documented by a number of studies (20–23), and if quality of life and economic data were to be better understood, this might become a part of the discussion surrounding the choice of therapy in the future.

Among the 543 patients who were treated with RAI therapy (average dose 16.5 mCi; 200 μCi/g), 92% had a successful outcome, and only 45 patients required a second form of treatment. This success rate is higher than the rates seen in previous studies. As such, a U.S. study reported the highest success rate of 86% previously using an average dose of 14.6 mCi (173 μCi/g) (24). At the other end of the spectrum, a German study reported a success rate of 71%, despite using a comparable dose of 15 mCi (25). Radiation thyroiditis occurred in 1.2% of patients, which is consistent with the 1% reported in the literature (26).

ATDs were the second most common therapy used in 99 (14%) of patients. In contrast, a number of European and South American studies found ATDs to be the most commonly chosen treatment used for 45–77% of patients (27,28). An almost equal proportion of patients opted for surgery (46% in one study) (29), and a close percentage chose RAI (36% in another study) (27). This reflects the huge disparity in the selection of therapy in different continents for various reasons (30–33).

In this study, 64 patients successfully completed long-term ATD therapy with a relapse rate of 27.4% after a mean follow-up of 2.64 years. The outcome is highly successful compared with a relapse rate of 64% as reported in a Cochrane systematic review (34), and comparable to a Swedish study (37% at three years) (35) and a Greek study (39% at four years) (36). The success rate in this study may be attributed to judicious selection of patients prior to initiating ATDs. Also, 25 patients discontinued ATDs prematurely due to adverse effects or persistent hyperthyroidism on the highest tolerable dose, resulting in an overall failure rate of 48%.

While in other studies relapse was generally found to occur within the first three to six months after ATDs were stopped (37), in the present study, the majority of patients (11) relapsed between 24 and 48 months, with the last documented relapse between 60 and 72 months, highlighting the importance of long-term follow-up.

The incidence of minor gastrointestinal, dermatologic, and rheumatologic adverse effects were consistent with the literature (38). Dysgeusia (an abnormal sense of taste), which has been reported to be rare, was seen in 11 patients (PTU: 7; MMI: 4). The incidence of transaminitis was 0.8%, which is consistent with the literature (39). Cholestasis developed in 0.8% of patients in this study, remaining a rare event, mainly due to MMI (38,40). No patient in the cohort developed severe liver failure, which is known to be associated with PTU with a frequency of 0.01% (41). Two patients in this study developed agranulocytosis, with an incidence of 0.8% that is comparable to other studies (0.1–0.6%) (42,43). One was due to PTU that resolved after drug discontinuation (the patient later underwent successful surgery), while the other was due to MMI, which also resolved after discontinuation (the patient was then successfully treated with RAI). Overall, ATD therapy resulted in a higher rate of adverse reactions (17.3%) compared with RAI (1.2%) and surgery (5.7%). This led to discontinuation of ATDs and a change of therapy in 58% of these patients. ATD therapy was also associated with a higher relapse rate (30%) compared with RAI therapy (8.3%).

Thyroidectomy, selected for 19 patients (first-line therapy by 2.6% of the cohort), had a 100% success rate and was relatively safe.

One (2.85%) patient who underwent thyroidectomy for GD had persistent hoarseness after injury of the superior laryngeal nerve. This compares with 3.7% in a multicenter Italian study reporting results of 14,934 surgeries (various types of thyroidectomy) over seven years for various thyroid diseases (44). No patient suffered injury of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN), although the incidence of temporary and permanent RLN injury in patients operated for GD has been reported to be 3.7–11.5% and 0–0.8%, respectively (45–47).

Postoperative hematoma can be a life-threatening complication requiring prompt surgical exploration. In the present cohort, only one (2.9%) patient experienced cervical hematoma that did not require surgical intervention. That compares favorably with the reported incidence of 1–3.7% of postoperative hematoma requiring surgical exploration (47,48) in similar patient populations. The incidence of permanent hypoparathyroidism following total thyroidectomy has been reported to be about 1% (49). No patient in this small cohort developed this complication, although two patients did not have adequate follow-up, and 8/35 (23%) patients experienced transient hypocalcemia. This latter finding is in line with the literature, which reports an incidence of 14–25% (47,50).

The incidence of postoperative complications varies widely between centers, reflecting the importance of surgical technique and patient selection. Ultimately, individual surgeon experience has a major impact on postoperative morbidity, with high-volume surgeons providing superior outcomes compared to low-volume surgeons (51).

Cost-effectiveness is another important factor for patients to consider while deciding treatment. In general, ATDs are more cost-effective, while total thyroidectomy is the least cost-effective (52). Since international differences in cost and health-insurance policies vary, physicians must discuss cost-effectiveness as pertinent to the region of practice.

The Mayo Clinic is a tertiary referral center and prone to referral bias. Hence, it is likely that some patients with favorable outcomes were not seen again at the institution after treatment of their GD, electing instead to be followed by their local physicians. In contrast, some patients who were lost to follow-up, especially those residing a long distance from the Mayo Clinic, may have been treated for relapse or adverse effects locally without the authors' knowledge. To attenuate these possible biases, the largest cohort reported to date has been used, and an attempt has been made to collect extensive follow-up data as much as possible.

In conclusion, RAI was the most commonly used modality within this cohort and demonstrated a good efficacy and safety profile. Surgery, while chosen infrequently, was also highly effective and relatively safe in the hands of experienced surgeons. While ATDs allow preservation of thyroid function while controlling hyperthyroidism, a high relapse rate combined with a significant adverse-effect profile was documented. While the goal of treatment for GD is to eliminate the hyperthyroid state, the choice of therapy for a particular patient not only depends on the clinical scenario, but also should reflect the patient's expectations of the disease course and treatment outcome. This requires in-depth discussion between physician and patient regarding the logistics, costs, recovery time, potential side effects, benefits, and drawbacks of each treatment option as it relates to that patient's medical circumstances, values, and preferences regarding therapy. The observations made in this large cohort study can inform this discussion.

Acknowledgments

NIH/NCRR CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024150 supported this study. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Brent GA. 2008. Clinical practice. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med 358:2594–2605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahn RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Garber JR, Greenlee MC, Klein I, Laurberg P, McDougall IR, Montori VM, Rivkees SA, Ross DS, Sosa JA, Stan MN; American Thyroid Association; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2011. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid 21:593–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh B, Singh A, Ahmed A, Wilson GA, Pickering BW, Herasevich V, Gajic O, Li G. 2012. Derivation and validation of automated electronic search strategies to extract Charlson comorbidities from electronic medical records. Mayo Clinic Proc 87:817–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peters H, Fischer C, Bogner U, Reiners C, Schleusener H. 1995. Radioiodine therapy of Graves' hyperthyroidism: standard vs. calculated 131iodine activity. Results from a prospective, randomized, multicentre study. Eur J Clin Invest 25:186–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tajiri J, Noguchi S. 2004. Antithyroid drug-induced agranulocytosis: special reference to normal white blood cell count agranulocytosis. Thyroid 14:459–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konkle B. 2012. Disorders of platelets and vessel wall. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. (eds) Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Eighteenth edition. McGraw Hill, New York, NY, pp 965–973 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young NS. 2012. Aplastic anemia, myelodysplasia, and related bone marrow failure syndromes. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J. (eds) Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. Eighteenth edition. McGraw Hill, New York, NY, pp 887–897 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shewan LG, Coats AJ. 2012. Adherence to ethical standards in publishing scientific articles: a statement from the International Journal of Cardiology. Int J Cardiol 161:124–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weetman AP. 2000. Graves' disease. N Engl J Med 343:1236–1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manji N, Carr-Smith JD, Boelaert K, Allahabadia A, Armitage M, Chatterjee VK, Lazarus JH, Pearce SH, Vaidya B, Gough SC, Franklyn JA. 2006. Influences of age, gender, smoking, and family history on autoimmune thyroid disease phenotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4873–4880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon B, Glinoer D, Lagasse R, Wartofsky L. 1990. Current trends in the management of Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 70:1518–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burch HB, Burman KD, Cooper DS 2012 A 2011. survey of clinical practice patterns in the management of Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:4549–4558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stan MN, Durski JM, Brito JP, Bhagra S, Thapa P, Bahn RS. 2013. Cohort study on radioactive iodine-induced hypothyroidism: implications for Graves' ophthalmopathy and optimal timing for thyroid hormone assessment. Thyroid 23:620–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Träisk F, Tallstedt L, Abraham-Nordling M, Andersson T, Berg G, Calissendorff J, Hallengren B, Hedner P, Lantz M, Nyström E, Ponjavic V, Taube A, Törring O, Wallin G, Asman P, Lundell G; Thyroid Study Group of TT 96 2009. Thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy after treatment for Graves' hyperthyroidism with antithyroid drugs or iodine-131. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:3700–3707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartalena L, Marcocci C, Bogazzi F, Manetti L, Tanda ML, Dell'Unto E, Bruno-Bossio G, Nardi M, Bartolomei MP, Lepri A, Rossi G, Martino E, Pinchera A. 1998. Relation between therapy for hyperthyroidism and the course of Graves' ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 338:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metso S, Auvinen A, Huhtala H, Salmi J, Oksala H, Jaatinen P. 2007. Increased cancer incidence after radioiodine treatment for hyperthyroidism. Cancer 109:1972–1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Fraser A, Nahshoni E, Weizman A, Leibovici L. 2006. Thyroxine–triiodothyronine combination therapy versus thyroxine monotherapy for clinical hypothyroidism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:2592–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nygaard B, Jensen EW, Kvetny J, Jarlov A, Faber J. 2009. Effect of combination therapy with thyroxine (T4) and 3,5,3′-triiodothyronine versus T4 monotherapy in patients with hypothyroidism, a double-blind, randomised cross-over study. Eur J Endocrinol 161:895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham-Nordling M, Törring O, Hamberger B, Lundell G, Tallstedt L, Calissendorff J, Wallin G. 2005. Graves' disease: a long-term quality-of-life follow up of patients randomized to treatment with antithyroid drugs, radioiodine, or surgery. Thyroid 15:1279–1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elbers L, Mourits M, Wiersinga W. 2011. Outcome of very long-term treatment with antithyroid drugs in Graves' hyperthyroidism associated with Graves' orbitopathy. Thyroid 21:279–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laurberg P, Berman DC, Andersen S, Bulow Pedersen I. 2011. Sustained control of Graves' hyperthyroidism during long-term low-dose antithyroid drug therapy of patients with severe Graves' orbitopathy. Thyroid 21:951–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mazza E, Carlini M, Flecchia D, Blatto A, Zuccarini O, Gamba S, Beninati S, Messina M. 2008. Long-term follow-up of patients with hyperthyroidism due to Graves' disease treated with methimazole. Comparison of usual treatment schedule with drug discontinuation vs continuous treatment with low methimazole doses: a retrospective study. J Endocrinol Invest 31:866–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Villagelin D, Romaldini JH, Santos RB, Milkos AB, Ward LS. 2015. Outcomes in relapsed Graves' disease patients following radioiodine or prolonged low dose of methimazole treatment. Thyroid 25:1282–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander EK, Larsen PR. 2002. High dose of (131)I therapy for the treatment of hyperthyroidism caused by Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:1073–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters H, Fischer C, Bogner U, Reiners C, Schleusener H. 1997. Treatment of Graves' hyperthyroidism with radioiodine: results of a prospective randomized study. Thyroid 7:247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross DS. 2011. Radioiodine therapy for hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med 364:542–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pineda G, Arancibia P, Mejía G. 1998. [Treatment of Basedow–Graves' hyperthyroidism: retrospective analysis after 30 years]. Rev Med Chil 126:953–962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tütüncü NB, Tütüncü T, Ozgen A, Erbas T. 2006. Long-term outcome of Graves' disease patients treated in a region with iodine deficiency: relapse rate increases in years with thionamides. J Natl Med Assoc 98:926–930 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sugrue D, McEvoy M, Feely J, Drury MI. 1980. Hyperthyroidism in the land of Graves: results of treatment by surgery, radio-iodine and carbimazole in 837 cases. Q J Med 49:51–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medeiros-Neto G, Romaldini JH, Abalovich M. 2011. Highlights of the guidelines on the management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid 21:581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita S, Amino N, Shong YK. 2011. The American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis guidelines: viewpoints from Japan and Korea. Thyroid 21:577–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearce EN, Hennessey JV, McDermott MT. 2011. New American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines for thyrotoxicosis and other forms of hyperthyroidism: significant progress for the clinician and a guide to future research. Thyroid 21:573–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kahaly GJ, Bartalena L, Hegedüs L. 2011. The American Thyroid Association/American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists guidelines for hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: a European perspective. Thyroid 21:585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abraham P, Avenell A, McGeoch SC, Clark LF, Bevan JS. 2010. Antithyroid drug regimen for treating Graves' hyperthyroidism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Mohlin E, Filipsson Nyström H, Eliasson M. 2014. Long-term prognosis after medical treatment of Graves' disease in a northern Swedish population 2000–2010. Eur J Endocrinol 170:419–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anagnostis P, Adamidou F, Polyzos SA, Katergari S, Karathanasi E, Zouli C, Panagiotou A, Kita M. 2013. Predictors of long-term remission in patients with Graves' disease: a single center experience. Endocrine 44:448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitti P, Rago T, Chiovato L, Pallini S, Santini F, Fiore E, Rocchi R, Martino E, Pinchera A. 1997. Clinical features of patients with Graves' disease undergoing remission after antithyroid drug treatment. Thyroid 7:369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper DS. 2005. Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med 352:905–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams KV, Nayak S, Becker D, Reyes J, Burmeister LA. 1997. Fifty years of experience with propylthiouracil-associated hepatotoxicity: what have we learned? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:1727–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Woeber KA. 2002. Methimazole-induced hepatotoxicity. Endocr Pract 8:222–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cooper DS, Rivkees SA. 2009. Putting propylthiouracil in perspective. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:1881–1882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Zhu YJ, Zhong JJ, Zhang J, Weng WW, Liu ZF, Xu Q, Dong MJ. 2016. Characteristics of antithyroid drug-induced agranulocytosis in patients with hyperthyroidism: a retrospective analysis of 114 cases in a single institution in China involving 9690 patients referred for radioiodine treatment over 15 years. Thyroid 26:627–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe N, Narimatsu H, Noh JY, Yamaguchi T, Kobayashi K, Kami M, Kunii Y, Mukasa K, Ito K, Ito K. 2012. Antithyroid drug-induced hematopoietic damage: a retrospective cohort study of agranulocytosis and pancytopenia involving 50,385 patients with Graves' disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosato L, Avenia N, Bernante P, De Palma M, Gulino G, Nasi PG, Pelizzo MR, Pezzullo L. 2004. Complications of thyroid surgery: analysis of a multicentric study on 14,934 patients operated on in Italy over 5 years. World J Surg 28:271–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barakate MS, Agarwal G, Reeve TS, Barraclough B, Robinson B, Delbridge LW. 2002. Total thyroidectomy is now the preferred option for the surgical management of Graves' disease. ANZ J Surg 72:321–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chiang FY, Lin JC, Wu CW, Lee KW, Lu SP, Kuo WR, Wang LF. 2006. Morbidity after total thyroidectomy for benign thyroid disease: comparison of Graves' disease and non-Graves' disease. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 22:554–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palestini N, Grivon M, Carbonaro G, Durando R, Freddi M, Odasso C, Sisto G, Robecchi A. 2005. [Surgical treatment of Graves' disease: results in 108 patients]. Ann Ital Chir 76:13–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cichoń S, Anielski R, Orlicki P, Krzesiwo-Stempak K. 2002. [Post-thyroidectomy hemorrhage]. Przegl Lek 59:489–492 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palit TK, Miller CC, Miltenburg DM. 2000. The efficacy of thyroidectomy for Graves' disease: a meta-analysis. J Surg Res 90:161–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barczyński M, Konturek A, Hubalewska-Dydejczyk A, Gołkowski F, Nowak W. 2012. Randomized clinical trial of bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy versus total thyroidectomy for Graves' disease with a 5-year follow-up. Br J Surg 99:515–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, Powe NR, Gordon TA, Udelsman R. 1998. The importance of surgeon experience for clinical and economic outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg 228:320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.In H, Pearce EN, Wong AK, Burgess JF, McAneny DB, Rosen JE. 2009. Treatment options for Graves disease: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Am Coll Surg 209:170–179.e1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]