Abstract

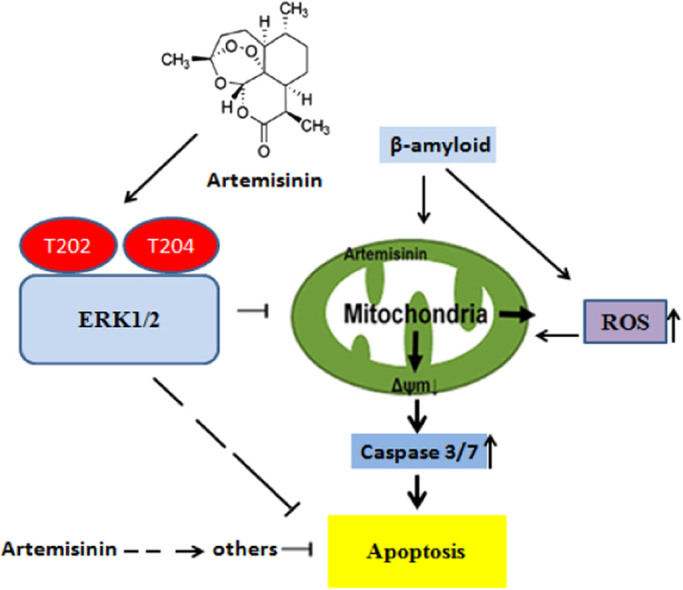

Accumulating evidence displays that an abnormal deposition of amyloid beta-peptide (Aβ) is the primary cause of the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD). And therefore the elimination of Aβ is regarded as an important strategy for AD treatment. The discovery of drug candidates using culture neuronal cells against Aβ peptide toxicity is believed to be an effective approach to develop drug for the treatment of AD patients. We have previously showed that artemisinin, a FDA-approved anti-malaria drug, has neuroprotective effects recently. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effects and potential mechanism of artemisinin in protecting neuronal PC12 cells from toxicity of β amyloid peptide. Our studies revealed that artemisinin, in clinical relevant concentration, protected and rescued PC12 cells from Aβ25–35-induced cell death. Further study showed that artemisinin significantly ameliorated cell death due to Aβ25–35 insult by restoring abnormal changes in nuclear morphology, lactate dehydrogenase, intracellular ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential and activity of apoptotic caspase. Western blotting analysis demonstrated that artemisinin activated extracellular regulated kinase ERK1/2 but not Akt survival signaling. Consistent with the role of ERK1/2, preincubation of cells with ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor PD98059 blocked the effect of artemisinin while PI3K inhibitor LY294002 has no effect. Moreover, Aβ1-42 also caused cells death of PC12 cells while artemisinin suppressed Aβ1-42 cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. Taken together, these results, at the first time, suggest that artemisinin is a potential protectant against β amyloid insult through activation of the ERK1/2 pathway. Our finding provides a potential application of artemisinin in prevention and treatment of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, PC12 cells, Aβ25–35, Artemisinin, ERK1/2

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

β-amyloid induced apoptosis in PC12 cells.

-

•

Artemisinin protected PC12 cells against β-amyloid-induced apoptosis.

-

•

Artemisinin activated ERK1/2 signaling pathway in PC12 cells.

-

•

Artemisinin protected PC12 cells against β-amyloid toxicity by ERK1/2 signaling pathway.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases refer to a range of neuronal disabilities associated with massive neuronal loss at the late stages of the diseases [1]. These neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Parkinson's disease (PD), and Huntington's disease (HD), are major problems worldwide [2]. NDs can cause by various reasons, including oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, inflammation, and apoptosis [3]. Along with the raise of extended life-expectancy and rapidly increasing prevalence in aging society, AD, the most common forms of NDs, is becoming a major economic, social, and healthcare burden throughout the world, and has been identified as a public health priority by the World Health Organization [4].

AD is the most common cause of dementia as well as the leading lethal disease among the elderly. It is characterized by the deposition of β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) and neuronal loss [5]. Aβ is produced in all neurons with significant non-pathological activity [6]. However, its aggregates are believed to be the principal component of senile plaques found in the brains of patients with AD [7], [8]. Therefore, the abnormal deposition of Aβ in plaques of brain tissue leads to a high diversity of toxic mechanisms, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial diffusion, and excitotoxicity through interactions with neurotransmitters receptors [9]. These effects could cause the loss of neurons, and synaptic lesions, all of which are considered to affect the memory [10]. Modulation of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity has emerged as a possible therapeutic approach to ameliorate AD onset and progression [11]. Development of safe and effective therapies for AD is of the highest priority for our aging society. Results of clinical trials with neurotrophic factors, however, have been rather disappointing because of the difficulty in delivering therapeutic proteins to the central nervous system [12]. The development of small molecules acting on neuronal cells has been proposed as an alternative [13]. Thus, identification of potential protective candidates to prevent and eliminate of excessive accumulation of Aβ is considered an important strategy for the treatment of AD.

Artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone, was originally isolated from the qinghao (the Chinese name of plant Artemisia annua L.) by Chinese scientists [14]. At present, artemisinins are among the most effective therapies for malaria with great safety and the preferred first-line treatment for the disease [15]. Except these effects, accumulated studies indicate that artemisinin and its derivatives have neuroprotective effect, therefore be potential candidates for treatment of AD [16], [17], [18]. Artemisinin easily penetrate the blood–brain barrier and we have previously showed that artemisinin was able to protect PC12 cells and cortical neurons from free radical/oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) [17], [19]. Free radical/oxidative stress is believed as a key player in Aβ peptide neuronal toxicity and it is most possible that artemisinin also can protect neuronal cells from Aβ induced injury. However, the action of artemisinins on Aβ-induced cell apoptosis which mimics the Aβ burden in vivo is not known.

Based on these observations, the purpose of this study was to assess whether artemisinins could protect against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells and the underlying mechanisms. In the present study, we found that the protective effect of artemisinin against Aβ-induced damage in PC12 cells was via restoring abnormal changes in nuclear morphology, intracellular ROS, mitochondrial membrane potential and caspase activation. We also investigated the roles of the ERK1/2 and Akt pathway in the protective effect of artemisinin. All of these may provide an interesting view of the potential application of artemisinins in future research for AD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Analytical grade artemisinin was purchased from Chengdu Kangbang Biotechnology Ltd. China. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro- 1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-benzimidazolyl-carbocyanineiodide (JC-1), and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Aβ25–35, Aβ1–42 and DMSO were obtained from Sigma (Sigma, US). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbi, anti-phospho-ERK1/2, anti-ERK1/2, anti-phospho-Akt473, anti-Akt,anti-GAPDH and anti-Tublin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Woburn, USA). PD98059 and LY294002 were obtained from Merck Millipore. Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate was purchased from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA). Gibcos fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin (PS) were purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY, USA).

2.2. Cell culture

PC12 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Gordon Guroff (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Cells were cultured in 75-cm2 flasks in DMEM supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% horse serum, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The medium was replaced every 2–3 days, and cells were sub-cultured by trypsin treatment twice a week, at a split of 1:4. Cells were seeded into 96-well, 48-well, or 6-well plates coated with 10 µg/ml poly-D-lysine and allowed to grow for at least 24 h.

2.3. MTT assay

PC12 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (coated with 10 μg/ml poly-D-lysine) at a density of 4–8×105 cells/-well in 1% serum medium for 24 h as previously described [20]. After serum starvation, the cultures were incubated with drugs or inhibitors for appropriate time, and then treated with Aβ; 24 h later MTT assay was performed. Then the cells were incubated with MTT (0.5 mg/ml) for additional 3 h. The medium was aspirated from each well and DMSO (200 μl) (Sigma, USA) was added. The absorbance of each well solution was obtained with a Multiskan Ascent Revelation Plate Reader (Thermo, USA) and the data are presented as Optical Density (OD) at wavelength of 570 nm. Assays were repeated at least three to six times in quadruplicate.

2.4. LDH assay

Cell cytotoxicity was measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the incubation medium when cellular membranes were destroyed. PC12 cells were seeded into 96-well plates (5×103 cells/-well). After appropriate treatment, the activity of released LDH in the medium was determined according to instructions of CytoTox-ONE™ Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay (Promega, USA). The fluorescent intensity was measured using Infinite M200 PRO Multimode Microplate at an excitation wavelength of 560 nm and emission at 590 nm. All values of % LDH released were normalized to the control group.

2.5. Detection of apoptotic nuclei by Hoechst 33342 staining

Apoptosis of cells was examined by staining with the DNA binding dye, Hoechst 33342 as previously described [21]. PC12 cell cultures were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 4 °C. Cells were then incubated with 10 µg/ml of Hoechst 33342 for 20 min to stain the nuclei. After washing with PBS for two times, the apoptotic cells were observed under a Fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan). Cells exhibiting condensed chromatin or fragmented nuclei were scored as apoptotic cells. For each Hoechst staining experiment, at least 200 cells in 5 random fields were collected and quantified. The data is presented as percentage of apoptotic cells (apoptotic cells/total cells×100).

2.6. Measurement of intracellular ROS levels

Intracellular ROS generation was assessed using CellROXs Deep Red Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). After appropriate treatment,the PC12 cells were incubated with CellROXs Deep Red Reagent (5 mM) in DMEM for 1 h in the dark, rinsed twice with 1x PBS solution and the fluorescence was observed and recorded using a fluorescent micro-scope at an excitation wavelength of 640 nm and an emission wavelength of 665 nm. Semiquantification of ROS level was evaluated by using Image-J software. All values of % ROS level were normalized to the control group.

2.7. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (△ψm)

JC-1 dye was used to monitor mitochondrial integrity. In brief, PC12 cells were seeded into black 96-well plates (1×104 cells/-well). After appropriate treatment, the PC12 cells were incubated with JC-1 (10 μg/ml in medium) at 37 °C for 15 min and then washed twice with PBS. For signal quantification, the intensity of red fluorescence (excitation 560 nm, emission 595 nm) and green fluorescence (excitation 485 nm, emission 535 nm) were measured using a Infinite M200 PRO Multimode Microplate. Mitochondrial membrane potential (△ψm) was calculated as the ratio of JC-1 red/green fluorescence intensity and the value was normalized to the control group. The fluorescent signal in the cells was also observed and recorded with a fluorescent microscope.

2.8. Caspase 3/7 activity assay

After treatment, the activity of caspase 3/7 was measured using the commercially available Caspase-Glos 3/7 Assay (Invitrogen, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, PC12 cells were lysed in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 12,500×g for 5 min 15 ml of cell lysate was incubated with 50 ml of 2X substrate working solution at room temperature for 30 min in 96-well plates. The fluorescence intensity was then determined by Infinite M200 PRO Multimode Microplate at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and emission at 520 nm. The fluorescence intensity of each sample was normalized to the protein concentration of sample. All values of % caspase 3/7 activities were normalized to the control group.

2.9. Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as previously described [22]. Cells from different experimental conditions were lysed with ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer. Protein concentration was measured with a BCA protein assay kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples with equal amounts of proteins were separated on 10% polyacrylamide gels, then were transferred to PVDF membrane, and probed with selective antibody respectively. The intensity of the bands was quantified using ImageJ software.

2.10. Data analysis and statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 statistical software (GraphPad software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Artemisinin concentration-dependently suppressed Aβ25-35 induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells

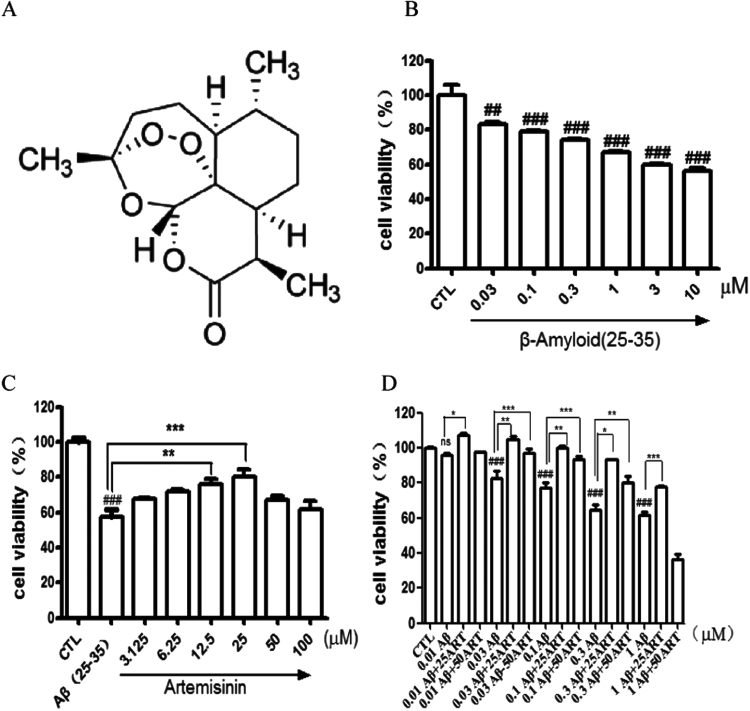

Aβ-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells was a common and reliable cellular toxicity model for AD related studies in vitro [23], [24], [25]. We first tested the cytotoxicity of the most usual used peptide Aβ25–35 (active component of Aβ peptides) on PC12 cells by MTT assay in our laboratory conditions. As shown in Fig. 1B, exposure of cells to different concentrations of Aβ25–35 for 24 h resulted in a notable decrease of the cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner, which indicated that Aβ25–35 could induce toxicity in PC12 cells. The toxicity was observed in the lowest dose of 0.03 μM and maximal in 3–10 μM. 0.3 μM Aβ25–35 was chosen in following experiment because of the 30–40% cell death was observed.

Fig. 1.

Artemisinin concentration-dependently suppressed Aβ25-35-induced cell viability lose in PC12 cells. (A) The structure of artemisinin. (B) Cells were treated with Aβ25-35 (0.03–10 μM) or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 24 h and cell viability was measured using the MTT assay(N=3). (C) Cells were pre-treated with artemisinin (3,125–100 μM) or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 1 h and then incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for a further 24 h and cell viability were measured by MTT assay (N=3). (D) PC12 cells were incubated with 0.1, 0.3, 1 μM Aβ25-35 for 30 min and post-treated with artemisinin (25 or 50 μM) for 24 h and cell viability were measured by MTT assay (N=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01,***P<0.005 versus the control or Aβ25-35 treated group as indicated; ###P<0.005 versus control group was considered statistically significant differences.

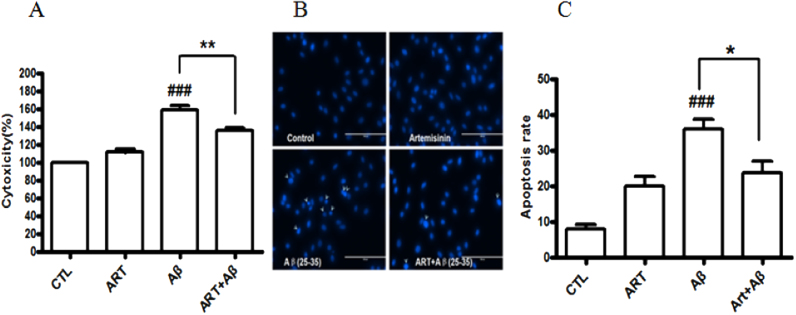

To evaluate the protective effects of artemisinin, PC12 cells were treated with artemisinin for 1 h before exposure to Aβ25-35 for 24 h. The result of MTT assay (Fig. 1C) revealed that the treatment of 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 resulted in dominant cell death (43%), whereas pretreatment with 12.5 and 25 μM of artemisinin significantly attenuated Aβ25-35- induced cell death. To clarify whether artemisinin could rescue cell from toxicity of Aβ25-35, PC12 cells were incubated with 0.1, 0.3, 1 μM Aβ25-35 for 30 min and post-treated with artemisinin (25 or 50 μM) for 24 h. The results (Fig. 1D) demonstrated that artemisinin not only can protected but also rescue PC12 cells against Aβ25-35-induced cell death. The protective activity of artemisinin was also confirmed by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. As shown in Fig. 2A, pre-treated cells with 25 μM of artemisinin for 1 h significantly reduced Aβ25-35-induced LDH leakage (from 160% to 135%). Nuclei condensation was observed in PC12 cells after exposure to Aβ25-35 in Hoechst 33342 staining assay (Fig. 2B). However, a pretreatment of 25 μM artemisinin definitely improved these changes (from 36% to 23%) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Artemisinin suppressed Aβ25-35-induced LDH release and apoptosis in PC12 cells. After pre-treatment with 25 μM artemisinin or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 1 h, PC12 cells were incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for another 24 h the release of LDH (A) was measured by LDH assay and the apoptosis cells (N=3) (B) was detected by staining with Hoechst 33342 and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. The number of apoptotic nuclei with condensed chromatin (C) was counted from the photomicrographs and presented as a percentage of the total number of nuclei (N=3). ###P<0.005 versus control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.005 versus the Aβ-treated group were considered statistically significant differences.

3.2. Artemisinin prevented Aβ25-35 induced ROS production in PC12 cells

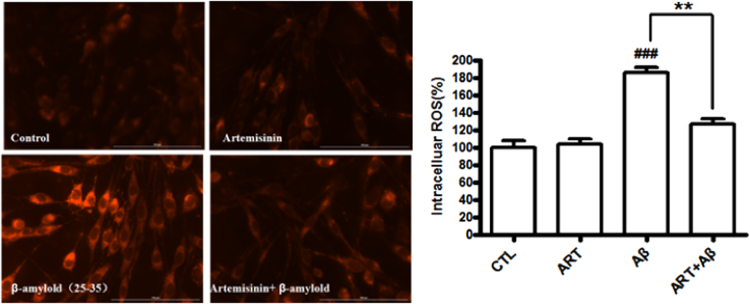

Previous studies reported that the toxicity of Aβ25-35 was mediated through the generation of ROS and our group also reported artemisinin can quench the ROS production [26], [27], [28]. Therefore, we investigated whether artemisinin blocked Aβ25-35-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Cellular oxidative stress was determined by the CellROXs Deep Red Reagent. PC12 cells were pretreated with or without 25 μM artemisinin for 1 h and then treated with Aβ25-35 for 24 h. As expected (Fig. 3), artemisinin significantly reduced the intracellular production of ROS induced Aβ25-35 (from 185.4% to126.6%).

Fig. 3.

Artemisinin reduced the increase of Aβ25-35-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells. After pre-treatment with 25 μM artemisinin or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 1 h, PC12 cells were incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for another 24 h. Intracellular ROS level was determined by the CellROXs Deep Red Reagent (N=3). ###P<0.005 versus control group; **P<0.01 versus Aβ-treated group was considered significantly different.

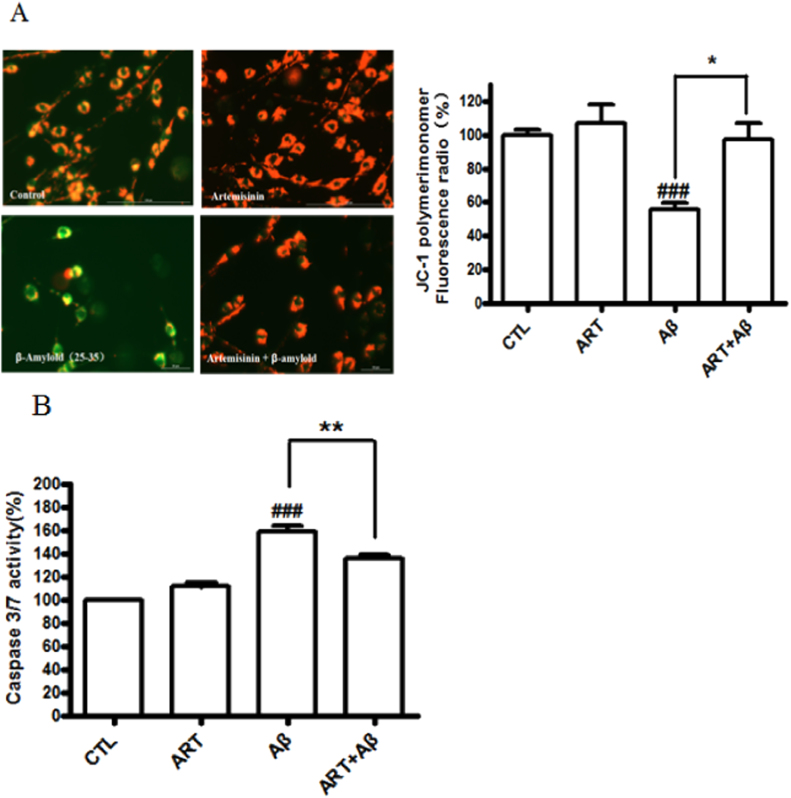

3.3. Artemisinin restored Aβ25-35 induced change of mitochondrial membrane potential and caspase 3/7 activity

Mitochondrial inhibition lead to the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (△ψm) involved in the progression of AD and neuron apoptosis caused by Aβ25-35 [29], [30], [31]. We elucidated whether artemisinin could reduce Aβ25-35-induced △ψm loss in further study. The △ψm in PC12 cells was assessed by analyzing the red/green fluorescent intensity ratio of JC-1 staining. The results (Fig. 4A) revealed that 25 μM artemisinin pretreatment significantly prevented the declined of mitochondrial membrane potential induced by Aβ25-35 (from 55.4% to 97.1%). Caspase 3/7 activation is a main biomarker in the apoptosis progress of neuronal cells [32]. As shown in Fig. 4B, treatment of cells with 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for 24 h increased caspase 3/7 activity to 159% compared to the control group. In contrast, pre-treatment with artemisinin significantly reduced caspase 3/7 activation to 135%.

Fig. 4.

Artemisinin attenuated Aβ-induced mitochondrial membrane potential (△ψm) loss and caspase 3/7 activity increase in PC12 cells. After pre-treatment with 25 μM artemisinin or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 1 h, PC12 cells were incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for another 24 h, △ψm was determined by the JC-1 assay (N=3) (Fig. 4A) and quantification of caspase 3/7 activity was determined by caspase 3/7 activity assay (N=3) (Fig. 4B). ###P<0.005 versus control group; *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus Aβ-treated group were considered significantly different.

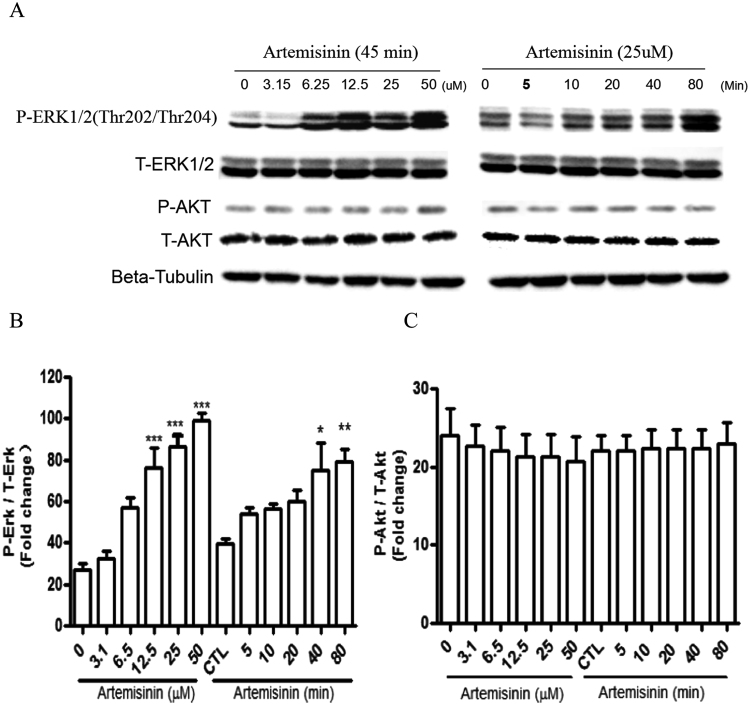

3.4. Artemisinin stimulated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in a time- and concentration-dependent manner in PC12 cells

It was widely accepted that ERK pathway phosphorylation is a key biochemical event responsible for cell survival and apoptosis [33], [34]. Previous studies indicated that artemisinin was able to activate ERK/CREB signaling in various cells [17], [18], [28], [35], [36]. We therefore tested whether ERK and Akt pathways are involved in artemisinin-induced neuroprotective effects in PC12 cells. As shown in Fig. 5A–C, phosphorylation of ERK1/2 but not Akt, gradually increased after the addition of artemisinin in a time- and dose-dependent fashion.

Fig. 5.

Artemisinin stimulated the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in a time- and concentration-dependent manner in PC12 cells. (A) The PC12 cells were collected with artemisinin treatment for different times (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 min) at 25 μM, or at different concentrations (3.15, 6.25, 12.5, 25 and 50 μM) for 45 min. The expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2, total ERK1/2, phosphorylated Akt, total Akt and beta-tubulin (A) were detected by Western blotting with specific antibodies. Quantification of representative protein band from Western blotting (B and C N=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005 versus the control group was considered significantly different.

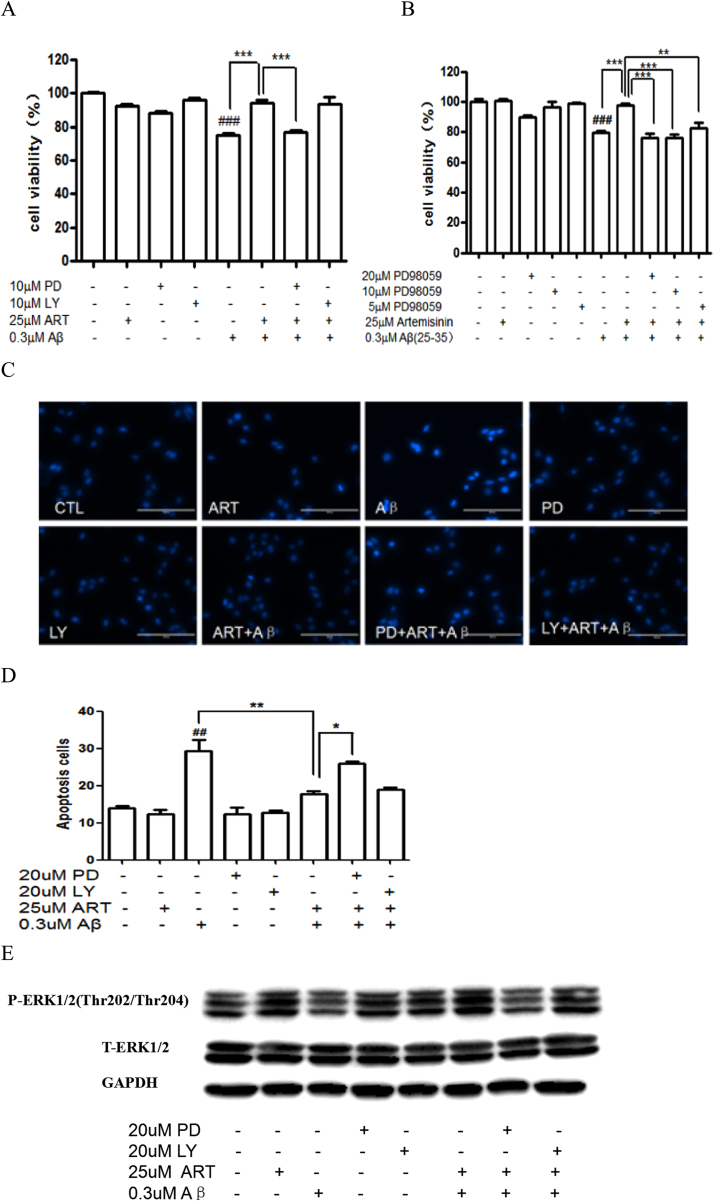

3.5. ERK 1/2 pathway mediated the protect effects of artemisinin in PC12 cells

We have previously reported that ERK1/2 pathway rather than PI3K pathway mediated the neuroprotective effects of artemisinin in cells against H2O2 or NO insult [18], [28]. In order to examine whether the up regulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is involved in the survival promoting effect of artemisinin on cell apoptosis induced by Aβ25-35, we investigated the effects of specific inhibitors for the ERK1/2 and PI3K pathways (the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor PD98059 and PI3K inhibitor LY294002) and we found that the ERK1/2 pathway inhibitor blocked the effects of artemisinin while LY294002, a PI3K kinase inhibitor had no effect (Fig. 6A). To further confirm the effects of ERK/1/2 pathway inhibitor PD98059 in more detail, the cultures preincubated with different concentrations of the ERK inhibitor PD98059 (5, 10, 20 μM) for 30 min were treated with artemisinin (25 μM) for 1 h, and the viability of cells was determined by the MTT assay after another 24 h. As shown in Fig. 6B, the protective effect of artemisinin was blocked in the presence of appropriate concentration of ERK inhibitor PD98059. Nuclei condensation was observed in PC12 cells treated with Aβ25-35 along in Hoechst 33342 staining assay, while pretreatment of cells with artemisinin (25 μM) for 1 h reversed the effect of Aβ25-35 (Fig. 6C). However, a pretreatment of PD98059 definitely abolished the effect of artemisinin (Fig. 6D). Western blot in Fig. 6E showed that Aβ25-35 was able to significantly down regulation the phosphorylation of ERK1/2, and artemisinin reversed decreased phosphorylation of ERK1/2, while PD98059 pretreatment blocked the reversed effects of artemisinin. The concentrations of inhibitors themselves used in the current experiments, had no effect on the cell death as shown. Thus these data put together suggested that the ERK1/2 pathway rather than the Akt pathway is mediating the protective effect of artemisinin.

Fig. 6.

ERK 1/2 pathway mediated the protect effects of artemisinin in PC12 cells. PC12 cells were pre-treated with10 μM PD98059 or 10 μM LY294002 (A), or 5, 10, 20 μM PD98059 (B) for 30 min, and treated with 25 μM artemisinin for 1 h, then incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for a further 24 h, and the cell viability was determined by MTT assay (N=3). PC12 cells were pre-treated with the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (20 μM) or PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM) for 30 min, and afterward treated with 25 μM artemisinin for 1 h, then incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35 for a further 24 h; the apoptosis cells was detected by staining with Hoechst 33342 and visualized by fluorescence microscopy (C). The number of apoptotic nuclei with condensed chromatin was counted from the photomicrographs and presented as a percentage of the total number of nuclei (N=3) (D). PC12 cells were pre-treated with the ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (20 μM) or PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (20 μM) for 30 min, and afterward treated with 25uM artemisinin for 1 h, then incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ25-35, The expression of phosphorylated ERK1/2, total ERK1/2; and GAPDH were detected by Western blotting with specific antibodies (N=3). ###P<0.005 versus control group; **P<0.01, ***P<0.005 versus the artemisinin or artemisinin plus Aβ25-35-treated group as indicated were considered significantly different.

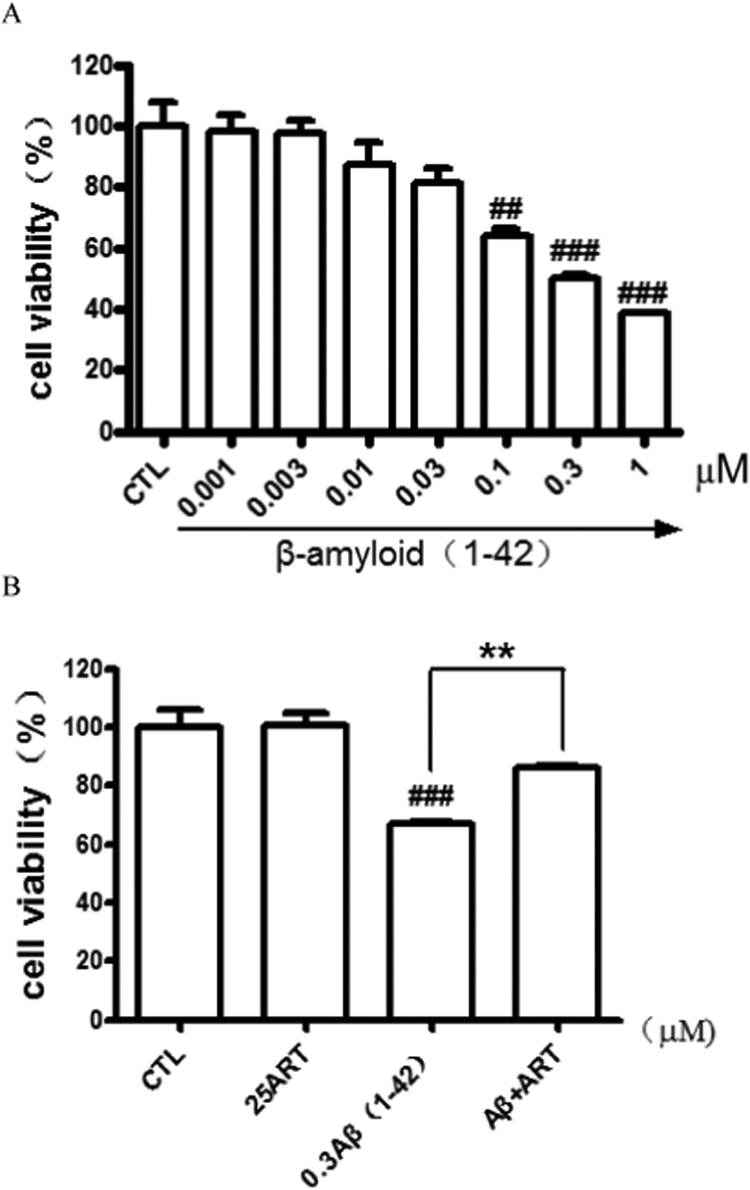

Because Aβ25–35 is a shorter toxic fragment (active component of Aβ1–42), people will desire to see the effect of Aβ1-42 itself on the PC12 cells and the protection of artemisinin on the toxic effect of Aβ1-42. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 7A, cells exposed to Aβ1-42 for 24 h resulted in a remarkable cell viability reduction, and as shown in Fig. 7B, artemisinin significantly protected PC12 cells from toxicity of Aβ1-42.

Fig. 7.

Artemisinin suppressed Aβ1-42-induced cell viability lose in PC12 cells. (A) Cells were treated with Aβ1-42 (0.001–1 μM) or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 24 h and cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. (B) Cells were pre-treated with artemisinin(25 μM) or 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) for 1 h and then incubated with or without 0.3 μM Aβ1-42 for a further 24 h and cell viability were measured by MTT assay (N=3). ###P<0.005 versus control group; **P<0.01 versus the Aβ1-42 treated group was considered statistically differences.

4. Discussion

At present study, we investigated protective effect of atemisinin on the toxic effect of beta amyloid on neuronal PC12 cells. Our results at the first time, showed that artemisinin, at therapeutic relevant concentration, protected and rescued neuronal cells from toxicity of beta amyloid peptides. Further experiments with various kinase inhibitors showed that the effect of artemisnin was mediated with the ERK1/2 pathway.

AD is a common and devastating neurodegenerative disorder, and its hallmark pathologic characteristics are β-amyloid plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and neuron progressive death [37]. Currently, due to rapidly aging populations, the prevalence of AD is growing exponentially and it becomes a huge burden on society and patients’ families [38], [39]. However, the pathogenesis of AD has not yet clearly been explained despite great progress in basic research, and there remains a dearth of effective treatments and cures. It is widely accepted that the formation and deposition of Aβ is one of the main typical pathological characteristics of AD brain [40]. Aβ is an amino acid peptide fragment derived by proteolysis from the integral membrane protein known as Aβ precursor protein [41]. The neurotoxicity of Aβ, including different Aβ fragments, has been widely reported [6]. Therefore how to inhibit the cell apoptosis induced by Aβ was attracting considerable and increasing concern of the public.

Recent reports indicate that artemisinin has neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects in PC12 cells [17], [18]. Firstly, artemether, a lipid-soluble derivative of artemisinin has been reported to possess anti-inflammatory properties by activated Nrf2 activity [16]. As we know, neuroinflammation played a major role in the formation of Aβ; besides, activated Nrf2 activity also shows benefits to AD in reports [42]. In addition, the reports have showed that artemisinin decreased BACE1 expression, and suppressed NF-kB activity and NALP3 activation [43]. Furthermore, it just reported that artemisinin was able to modulate GABA (A) receptor signaling, while the GABA(A) receptor signaling was seriously altered in aging and AD [44], [45]. In our present experiment, we explored whether artemisinin treatment could attenuate PC12 cells apoptosis due to Aβ25–35 exposure. In line with other reports, we found that Aβ25–35 was cytotoxicity to PC12 cells and showed a concentration-dependent manner [27]. In addition, data from Hoechst 33342 staining assay showed that the Aβ25–35 also induced the apoptosis of PC12 cells. When pretreated with artemisinin, the cell viability of PC12 cell incubated with Aβ25–35 was strikingly increased (Fig. 1). Additionally, artemisinin also attenuated the apoptosis in PC12 cells induced by Aβ25–35, which further implies that artemisinin confer protective effects on PC12 cells insult with Aβ25–35 (Fig. 2).

It's widely accepted that ROS was one of the indicators of oxidative stress and associated with a large array of neurological diseases and brain ageing itself [10]. Reports confirmed that the presence of diffuse ROS resulted in oxidative stress of the entire brain in AD cases [46]. Our previous study showed that H2O2 increased the oxidative stress injury through elevating ROS production and artemisinin significantly attenuated H2O2-induced ROS accumulation [28]. Here, we found that Aβ25–35 resulted in the collapse of the △ψm and increase of ROS in PC12 cells while pretreatment of artemisinin significantly suppress these abnormal changes in PC12 cells (Fig. 3). The decrease of cell viability and the increase of LDH release caused by Aβ25–35 were significantly suppressed by artemisinin, suggesting that antioxidant activity of artemisinin contributes to its protective effects.

Increased mitochondrial DNA damage and protein loss of election transport chain in neuron have been found in AD patients, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in the process of AD [10], [29]. Mitochondrial apoptotic pathway due to mitochondria deficiency plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of AD [47]. It has been reported that strategies to block mitochondrial apoptotic pathway are potential therapeutics to prevent cells death. In this study, our results showed that Aβ25–35-induced △ψm loss could be suppressed by pretreatment with artemisinin. The increase of intracellular ROS induced by Aβ25–35, leads to damage to the mitochondrial membrane and results in the collapse of the △ψm and activation of the apoptotic cascade. Pre-treatment with artemisinin was able to suppress the activation of caspase 3/7 (Fig. 4).

ERK1/2 pathway is a key signaling component that plays a crucial role in the initiation and regulation of most of stimulated cellular processes such as proliferation, survival and apoptosis [34]. This pathway is reported as a key signaling to induce cellular antioxidant mechanism [48]. Our data suggest that activation of ERK 1/2 pathway plays a critical role in artemisinin-induced neuron protective effects against Aβ25–35 insult; artemisinin stimulated phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 (Fig. 5), which is consistent with activation of the ERK1/2 classes, artemisinin triggered neuroprotective effects against cell viability lose and cell apoptosis was attenuated by specific pharmacological inhibitors of MEK, an upstream kinase of ERK1/2 kinase (Fig. 6). Therefore, these results provide mechanistic evidence to support the notion that artemisinin-regulated protective effects against Aβ25–35 injury occur via ERK 1/2 activation.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that artemisinin is able to reduce Aβ-induced insult in PC12 cells through the regulation of multiple mechanisms including (1) suppressing the LDH release; (2) restraining the production of intracellular ROS; (3) modulating △ψm and caspase 3/7 dependent pathway; (4) activating ERK1/2 signaling. The protective effects of artemisinin to attenuate Aβ-mediated intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway are, at least in part, mediated via the activation of ERK1/2 kinase signaling rather than Akt signaling. Our results offer support for the potential development of artemisinin to prevent neuronal cells death in the process of AD, although the effects of artemisinin in vivo required further investigations.

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the Guangdong Provincial Project of Science and Technology (2011B050200005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371088), SRG2015-00004-FHS and MYRG2016–00052-FHS from University of Macau, and the Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) of Macao (FDCT 021/2015/A1 and FDCT 016/2016/A1).

References

- 1.Vila M., Przedborski S. Targeting programmed cell death in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4(5):365–375. doi: 10.1038/nrn1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forman M.S., Trojanowski J.Q., Lee V.M. Neurodegenerative diseases: a decade of discoveries paves the way for therapeutic breakthroughs. Nat. Med. 2004;10(10):1055–1063. doi: 10.1038/nm1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor J.P., Hardy J., Fischbeck K.H. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 2002;296(5575):1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colucci L. Alzheimer's disease costs: what we know and what we should take into account. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(4):1311–1324. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selkoe D.J. Alzheimer's disease is a synaptic failure. Science. 2002;298(5594):789–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1074069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esteban J.A. Living with the enemy: a physiological role for the beta-amyloid peptide. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wisniewski T., Ghiso J., Frangione B. Biology of A beta amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 1997;4(5):313–328. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1997.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng W.H. Amyloid beta peptide induces tau phosphorylation and loss of cholinergic neurons in rat primary septal cultures. Neuroscience. 2002;115(1):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00404-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han S.H., Park J.C., Mook-Jung I. Amyloid beta-interacting partners in Alzheimer's disease: from accomplices to possible therapeutic targets. Prog. Neurobiol. 2016;137:17–38. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cavallucci V., D'Amelio M., Cecconi F. Abeta toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012;45(2):366–378. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo J. Cross-interactions between the Alzheimer disease amyloid-beta peptide and other amyloid proteins: a further aspect of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291(32):16485–16493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.714576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartus R.T., Johnson E.M., Jr. Clinical tests of neurotrophic factors for human neurodegenerative diseases, part 1: where have we been and what have we learned? Neurobiol. Dis. 2017;97(Pt B):156–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraldo E. Abeta and tau toxicities in Alzheimer's are linked via oxidative stress-induced p38 activation: protective role of vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2014;2:873–877. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tu Y. The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 2011;17(10):1217–1220. doi: 10.1038/nm.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Visser B.J., van Vugt M., Grobusch M.P. Malaria: an update on current chemotherapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2014;15(15):2219–2254. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.944499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okorji U.P. Antimalarial drug artemether inhibits neuroinflammation in BV2 microglia through Nrf2-dependent mechanisms. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53(9):6426–6443. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9543-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarina Induction of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells by artemisinin through activation of ERK and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Brain Res. 2013;1490:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng W. Artemisinin conferred ERK mediated neuroprotection to PC12 cells and cortical neurons exposed to sodium nitroprusside-induced oxidative insult. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;97:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gautam A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of endoperoxide antimalarials. Curr. Drug Metab. 2009;10(3):289–306. doi: 10.2174/138920009787846323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng Z. Lithium ions attenuate serum-deprivation-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells through regulation of the Akt/FoxO1 signaling pathways. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(5):785–794. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4168-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H. The role of Akt/FoxO3a in the protective effect of venlafaxine against corticosterone-induced cell death in PC12 cells. Psychopharmacology. 2013;228(1):129–141. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng Z. The atypical antipsychotic agent, clozapine, protects against corticosterone-induced death of PC12 cells by regulating the Akt/FoxO3a signaling pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9904-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang Y.W. Maslinic acid protected PC12 cells differentiated by nerve growth factor against beta-amyloid-induced apoptosis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015;63(47):10243–10249. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li R.C. Neuroglobin protects PC12 cells against beta-amyloid-induced cell injury. Neurobiol. Aging. 2008;29(12):1815–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ivins K.J. Multiple pathways of apoptosis in PC12 cells. CrmA inhibits apoptosis induced by beta-amyloid. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274(4):2107–2112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jang J.H., Surh Y.J. Protective effect of resveratrol on beta-amyloid-induced oxidative PC12 cell death. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34(8):1100–1110. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu P. Triptolide inhibited cytotoxicity of differentiated PC12 cells induced by amyloid-Beta25-35 via the autophagy pathway. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chong C.M., Zheng W. Artemisinin protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage through activation of ERK/CREB signaling. Redox Biol. 2016;9:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abramov A.Y., Canevari L., Duchen M.R. Beta-amyloid peptides induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in astrocytes and death of neurons through activation of NADPH oxidase. J. Neurosci. 2004;24(2):565–575. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4042-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang C.P. Beneficial effect of Astragaloside on Alzheimer's disease condition using cultured primary cortical cells under beta-amyloid exposure. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53(10):7329–7340. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9623-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan A. Attenuation of Abeta-induced neurotoxicity by thymoquinone via inhibition of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2012;369(1–2):55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang D. The steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone promotes the cytoplasmic localization of Yorkie to suppress cell proliferation and induce apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291(41):21761–21770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.719856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darling N.J., Cook S.J. The role of MAPK signalling pathways in the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1843(10):2150–2163. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miloso M. MAPKs as mediators of cell fate determination: an approach to neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15(6):538–548. doi: 10.2174/092986708783769731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu J.J. Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis in HL-60 leukemia cells dependent of iron and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation but independent of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7(7):1017–1023. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee I.S. Artesunate activates Nrf2 pathway-driven anti-inflammatory potential through ERK signaling in microglial BV2 cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;509(1):17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marotta C.A., Majocha R.E., Tate B. Molecular and cellular biology of Alzheimer amyloid. J. Mol. Neurosci. 1992;3(3):111–125. doi: 10.1007/BF02919403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shah H. Research priorities to reduce the global burden of dementia by 2025. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(12):1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh S. Current therapeutic strategy in Alzheimer's disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;16(12):1651–1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hubin E. Transient dynamics of Abeta contribute to toxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71(18):3507–3521. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1634-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukatsu R. Biological characteristics of amyloid precursor protein and Alzheimer's disease. Rinsho Byori. 1996;44(3):213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jan A. eEF2K inhibition blocks Abeta42 neurotoxicity by promoting an NRF2 antioxidant response. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1634-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi J.Q. Antimalarial drug artemisinin extenuates amyloidogenesis and neuroinflammation in APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice via inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2013;19(4):262–268. doi: 10.1111/cns.12066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rissman R.A., De Blas A.L., Armstrong D.M. GABA(A) receptors in aging and Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2007;103(4):1285–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li J. Artemisinins target GABAA receptor signaling and impair alpha cell identity. Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim G.H. The role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 2015;24(4):325–340. doi: 10.5607/en.2015.24.4.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Onyango I.G., Khan S.M. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and stress signaling in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(4):339–349. doi: 10.2174/156720506778249489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu Q. The antioxidant, immunomodulatory, and anti-inflammatory activities of Spirulina: an overview. Arch. Toxicol. 2016;90(8):1817–1840. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1744-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]