Abstract

Globally, blue carbon (i.e., carbon in coastal and marine ecosystems) emissions have been seriously augmented due to the devastating effects of anthropogenic pressures on coastal ecosystems including mangrove swamps, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows. The greening of aquaculture, however, including an ecosystem approach to Integrated Aquaculture-Agriculture (IAA) and Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) could play a significant role in reversing this trend, enhancing coastal ecosystems, and sequestering blue carbon. Ponds within IAA farming systems sequester more carbon per unit area than conventional fish ponds, natural lakes, and inland seas. The translocation of shrimp culture from mangrove swamps to offshore IMTA could reduce mangrove loss, reverse blue carbon emissions, and in turn increase storage of blue carbon through restoration of mangroves. Moreover, offshore IMTA may create a barrier to trawl fishing which in turn could help restore seagrasses and further enhance blue carbon sequestration. Seaweed and shellfish culture within IMTA could also help to sequester more blue carbon. The greening of aquaculture could face several challenges that need to be addressed in order to realize substantial benefits from enhanced blue carbon sequestration and eventually contribute to global climate change mitigation.

Keywords: Aquaculture, Blue carbon, Climate change, Coastal ecosystems, Mitigation

Introduction

Anthropogenic climate change is caused by emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) notably carbon from dust particles “black carbon,” fossil fuels “brown carbon,” terrestrial ecosystems “green carbon,” and coastal and marine ecosystems “blue carbon” (Nellemann et al. 2009). Blue carbon is an important part of the global carbon cycle, and coastal and marine ecosystems play a significant role in the blue carbon cycle. Blue carbon considered in this review is the carbon sequestered, stored, and released from three major coastal and marine ecosystems: (1) mangrove swamps, (2) salt marshes, and (3) seagrass meadows (Murray et al. 2011; Pendleton et al. 2012; Siikamäki et al. 2013). Vegetated coastal habitats are hotspots for ecosystem functions, including blue carbon sinks1 (Mcleod et al. 2011; Fourqurean et al. 2012; Greiner et al. 2013). These three habitats are commonly referred to as “blue carbon ecosystems” which cover <0.5% of the global seabed; however, some authors estimate that they are responsible for capturing and storing2 up to 71% of global blue carbon (Nellemann et al. 2009). Global coverage of blue carbon ecosystems is 509 170 km2 of which 319 000 km2 (63%) is seagrasses, 139 170 km2 (27%) is mangroves, and 51 000 km2 (10%) is salt marshes. Globally, these coastal ecosystems store about 11.5 billion tons of blue carbon. The highest blue carbon pool is mangroves (6.5 billion tons), followed by seagrasses (3 billion tons) and salt marshes (2 billion tons). Globally, the blue carbon sequestration3 rate is about 53 million tons annually, of which 26 million tons (49%) is in seagrasses, 16 million tons (30%) in mangroves, and 11 million tons (21%) in salt marshes (Siikamäki et al. 2012).

Unlike blue carbon ecosystems, seaweeds4 or marine macroalgal communities do not develop their own organic-rich sediments as they primarily grow on hard rocky substrates, and thus, do not directly contribute to carbon sequestration (Duarte et al. 2013). Nevertheless, macroalgae have the potential to contribute to global blue carbon sequestration by acting as a carbon donor to receiver sites where organic materials accumulate (Hill et al. 2015). Under certain conditions, macroalgae can serve as an effective CO2 sink due to their capacity for photosynthetically driven CO2 assimilation (Chung et al. 2011, 2013).

Globally, coastal ecosystems are among the most threatened and rapidly disappearing natural ecosystems. One-third of the world’s blue carbon ecosystems have already been lost over recent decades (Mcleod et al. 2011). The estimated annual loss5 of blue carbon ecosystems is ~0.5–3%, amounting to ~8000 km2 per year (Waycott et al. 2009; Spalding et al. 2010; Pendleton et al. 2012). Nearly, 100% of mangroves and 30–40% of tidal marshes and seagrasses could be lost in the next 100 years (Duke et al. 2007; IPCC 2007). The global economic impacts for degradation of blue carbon ecosystems have been estimated to be worth US$6–42 billion annually (Pendleton et al. 2012). Blue carbon emissions are being critically augmented due to devastating effects on coastal ecosystems, driven by agriculture, aquaculture, deforestation, dredging, land-use change, industrial runoff, mining, oil spills, overfishing, pollution, tourism, and urbanization (Valiela et al. 2001; Gordon et al. 2011; Murray et al. 2011; Pendleton et al. 2012). Globally, the blue carbon emission rate is 58.7 million tons annually, of which 33.5 million tons (57%) is from mangroves, 14.7 million tons (25%) from seagrasses, and 10.5 million tons (18%) from salt marshes (Siikamäki et al. 2012).

Emissions of carbon along with other GHG (CH4, N2O) have been recognized as the dominant cause of climate change (IPCC 2014). To tackle climate change, it is crucial to reduce blue carbon emissions from coastal ecosystems. Sustainable management of coastal ecosystems can help to reduce blue carbon emissions and contribute to blue carbon sequestration (Mcleod et al. 2011; Pendleton et al. 2012; Duarte et al. 2013). The greening of aquaculture could be a part of sustainable coastal ecosystem management (Moss et al. 2001; Rajagopal et al. 2006; Hersoug 2015), which could reduce carbon emissions (Hanson et al. 2011). Moreover, the greening of aquaculture could play an important role in sequestering blue carbon (Sepúlveda-Machado and Aguilar-González 2015; Ahmed and Glaser 2016). The aim of this article is to highlight key issues for sequestering blue carbon through the greening of aquaculture.

Greening of aquaculture

The greening of aquaculture includes concepts such as an Ecosystem Approach to Aquaculture (EAA), Integrated Aquaculture-Agriculture (IAA), and Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA). Greening is defined as the process of making changes to aquaculture production so that they are more environmentally friendly (Burch et al. 2001). The thematic focus of greening aquaculture is to improve fish production and at the same time significantly reduce environmental impacts. Rapid development of aquaculture has been advocated as an approach to increasing food production in order to contribute to human nutrition and food security (Simpson 2011; FAO 2016). However, this has led to a number of social, economic, and environmental constraints. The greening of aquaculture is needed to balance the adverse effects of the blue revolution of aquaculture as it has been practiced until now (Moss et al. 2001; Ahmed and Toufique 2015). Considerable debate and arguments have occurred about the impacts of the blue revolution on the environment and society (Neori et al. 2007; Hall et al. 2011). Social, economic, and environmental challenges must be addressed to realize the benefits of the blue revolution. The greening of aquaculture is based on ecologically and socially responsible decision-making and translating this into action for sustainable development. Greening of the blue revolution does not only make environmental sense, but also addresses social and economic concerns (Moss et al. 2001; Ahmed and Toufique 2015). Thus, the blue revolution of aquaculture must be accompanied by favorable social, economic, and ecological contexts to be sustained over time (White et al. 2004; Neori et al. 2007). Future development of aquaculture must reorient the blue revolution to attain ecologically integrated and more sustainable aquaculture systems that have positive impacts on natural and social ecosystems (Costa-Pierce 2002, 2008).

Ecosystem Approach to Aquaculture (EAA)

EAA is a strategy for integration of aquaculture within the wider ecosystem in such a way that it promotes sustainable development, equity, and resilience of interlinked social and ecological systems (Soto et al. 2008). An EAA includes management to increase ecosystem productivity through aquaculture and the development of linkages between aquaculture, environment, and society to promote economic benefits. An EAA should maximize not only economic, but also social and environmental benefits. An EAA should be technically sophisticated, ecologically accountable, and socially responsible (Costa-Pierce 2008). An EAA acknowledges the need to achieve profitability and the potential of aquaculture development to deliver gains from social and environmental perspectives (Knowler 2008). EAA has also been termed “ecological aquaculture” that encompasses integrated management of land, water, and aquatic living resources for sustainability (Costa-Pierce 2008). Implementation of EAA requires understanding ecosystem functions and changes in human behavior. An EAA should be structured to deal effectively with issues of a social, economic, environmental, technical, physical, and political nature. These factors can facilitate sustainable development and management of aquaculture to provide a full range of ecosystems functions and services, while not posing a significant risk to the environment or society. Three spheres of EAA application are important: (1) farm-which is crucial for management practices in the production processes, (2) water body and associated aquaculture zone—water body is the portion or the whole of the ecosystem where the farm concentrates on aquaculture operations, and (3) market and trade—the business model of food supply with global safety standards (Soto et al. 2008).

Integrated Aquaculture-Agriculture (IAA)

IAA is defined as concurrent or sequential linkages between two or more aquaculture and agricultural activities, including the integration of fish, rice, vegetables, fruits, and livestock (Prein 2002). In a wider perspective, the integration and diversification of IAA has been observed as part of integrated resources management, and improved natural resource-use efficiency. Ideally, IAA results in increased productivity, profitability, and sustainability (Pant et al. 2004; Dey et al. 2010). IAA is particularly appropriate for resource-poor farmers, maximizing benefits from land, water, and labor. In developing countries where land is scarce and the population is growing rapidly, IAA makes the most of scarce resources, since there are synergistic benefits between different enterprises. There are two major types of IAA systems depending on biophysical conditions: (1) pond-based IAA and (2) rice-fish culture (Ahmed et al. 2014). Fish are grown as a primary crop in pond-based IAA, while rice is the main crop in rice-fish farming. In general, IAA requires less off-farm inputs including chemical fertilizers and pesticides as fish waste increases the amount of organic fertilizer by recycling nutrients (Prein 2002). At the same time, rice fields and ponds offer benthic, periphytic, and planktonic food for fish. Moreover, a variety of aquatic weeds (azolla, duckweed, water hyacinth, and water spinach) are grown in ponds and rice fields that are consumed by fish. Fish farming in rice fields is also regarded as an approach to integrated pest management (Halwart and Gupta 2004). Because of waste utilization and pest control, IAA could be a form of good aquaculture practices that display inherent biological, chemical, and physical precautionary measures to prevent pathogen contamination and the outbreak of disease (Serfling 2015). To avoid public health hazards, farmers should be trained to follow good aquaculture practices in IAA regarding the application of inputs, including chemicals and livestock manures.

Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA)

IMTA is a process of growing different species of finfish and shellfish with seaweeds from different trophic levels in an integrated farm to increase productivity and profitability through efficient recycling and reuse of nutrients. IMTA is a practice in which the by-products from one species are recycled to become inputs for another. The principle of IMTA is the co-cultivation of fed-fish, extractive species for organic particles (shellfish), and assimilative species for inorganic nutrients (seaweeds) (Troell et al. 2009; Chopin 2011; Chopin et al. 2012). The concept of IMTA is to create balanced systems to improve environmental sustainability, economic viability, and social acceptability. IMTA seems to solve some negative environmental effects of aquaculture, and it has economic benefits because farm diversification generates additional income while reducing risks (Barrington et al. 2009, 2010). IMTA is adaptable for land-based and offshore aquaculture systems in both freshwater and saltwater environments. IMTA is currently operated in over 40 countries on a commercial or experimental basis, including Canada, Chile, China, Japan, the USA, and many European countries (Chopin 2011). IMTA could be a solution to environmental problems associated with the intensification of aquaculture production, and is a more diverse and less costly approach for the ecological management of aquaculture (Klinger and Naylor 2012). IMTA is a biomitigative approach, which reduces environmental impacts of aquaculture and other nutrient discharges by growing diverse food crops in productive systems (Diana et al. 2013).

Blue carbon sequestration

Pond-based IAA

Fish ponds play a significant role in carbon sequestration due to the accumulation of organic matter in pond sediments. Fish feeds and fertilizers are applied in ponds for growth of fish, and these inputs stimulate organic carbon production by phytoplankton photosynthesis (Boyd and Tucker 1998). Phytoplankton, also known as microalgae, are among the most efficient biological systems for capturing carbon owing to their ability to transport bicarbonate into their cells (Sayre 2010). Macrophytes also have potential for carbon capture in ponds (Stepien et al. 2016). Organic carbon in pond sediments increases soil fertility that can stimulate production of benthic organisms and rooted plants, and thus, increases fish productivity through increased food availability. Fish ponds can sequester carbon at a rate of 1.5 t ha−1 annually (Boyd et al. 2010). In India, the annual carbon sequestration rate in fish ponds is from 0.86 to 1.53 t ha−1. At this rate, total average annual carbon sequestration from 0.79 million ha of fish ponds is 0.9 million tons, which is 0.2% of Indian annual carbon emissions (Adhikari et al. 2012). Globally, the annual carbon sequestration is 16.6 million tons from 11.08 million ha of aquaculture area worldwide, representing about 0.21% of global annual carbon emissions (Boyd et al. 2010).

Agriculturally eutrophic6 impoundments as well as IAA ponds sequester carbon at an average rate of 21.2 t ha−1 annually which is 14 times higher than standard fish ponds. Moreover, carbon sequestration within agriculturally eutrophic impoundments is 30 times higher than in small natural lakes, and 400 times greater than in large natural lakes and inland seas. The global annual carbon sequestration rate is about 163 million tons from 7.7 million ha of agriculturally eutrophic impoundments (Downing et al. 2008). If 25% of global aquaculture area (4.5 of 18 million ha)7 were converted to agriculturally eutrophic impoundments as well as IAA, an additional 95.4 million tons of carbon could be sequestered annually (Table 1).

Table 1.

Potential for blue carbon sequestration through the greening of aquaculture

| Greening aquaculture | Proposed management | Potential area (ha) or productiona (t year−1) | Carbon sequestration rateb (t ha−1 year−1 or t per t yield year−1) | Total carbon sequestrationc (million t year−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAA | Conversion (25%) | 4.5 million ha | 21.2 | 95.40 |

| Mangrove | Regeneration (25%) | 0.47 million ha | 1.15–1.39 | 0.54–0.65 |

| Seagrass | Restoration (25%) | 0.82 million ha | 0.54–0.83 | 0.44–0.68 |

| Shellfish | Increase yield (25%) | 4.03 million t | 0.06–0.12 | 0.24–0.48 |

| Overall | ≈97 |

aIAA area is from discussions with various scholars; mangrove and seagrass area are from Valiela et al. (2001) and Walker et al. (2006), respectively; shellfish production is from FAO (2016)

bCarbon sequestration rates are from: IAA (Downing et al. 2008), mangroves (Bouillon et al. 2008; Nellemann et al. 2009; Siikamäki et al. 2012), seagrasses (Duarte et al. 2005; Siikamäki et al. 2012), and shellfish (SARF 2012)

cCarbon sequestration rate expected in standard ponds may reduce potential gain from conversion to IAA, however, it was not considered here

Mangroves to IMTA: Translocation of shrimp farming

In addition to being a blue carbon sink, mangroves provide a wide range of services, including biodiversity conservation, secondary production, nutrient cycling, and adaptation to climate change (Huxham et al. 2010; Donato et al. 2011; Duarte et al. 2013; Saenger et al. 2013; Alongi 2014). However, the loss of mangroves accelerated rapidly in the 1980s and 1990s where shrimp farming was one of the key reasons. About 1.89 million ha of global mangrove loss resulted from coastal aquaculture including shrimp farming (Valiela et al. 2001). Most aquaculture-related damage was caused by the conversion of mangrove swamps to shrimp ponds with other detrimental effects caused by effluent discharges from intensive farms. Driven by high economic returns associated with growing demand in the international market, unplanned and unregulated shrimp farming caused widespread destruction of mangroves in a number of countries, including Bangladesh, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam (FAO 2007; UNEP 2014). To protect against further loss of mangroves, the “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD+)” program could be implemented more widely and help to reduce CO2 emissions through conservation of mangroves (Gordon et al. 2011; UNEP 2014; Ahmed and Glaser 2016).

The translocation of shrimp culture from mangrove forests to offshore IMTA located near the coast can be environmentally friendly. Shrimp culture has already been introduced in IMTA in many countries (Barrington et al. 2009). The translocation of shrimp farming from mangroves to IMTA would reduce blue carbon emissions and help facilitate mangrove regeneration through replanting. Payments for ecosystem services through a scheme of blue carbon offsets could significantly enhance prospects for mangrove restoration (Locatelli et al. 2014). Mangrove forests sequester blue carbon at a rate of 1.15–1.39 t ha−1 annually (Bouillon et al. 2008; Nellemann et al. 2009; Siikamäki et al. 2012). If translocation of shrimp culture occurred and it could rehabilitate 25% of the deforested mangrove area globally (0.47 million ha), it could sequester another 0.54–0.65 million tons of blue carbon annually (Table 1). The estimated blue carbon sequestration rates in the scenarios presented are representative and the rate of uptake and duration of storage will depend on the management of the systems. Sequestration rates assumed for mangroves may also vary depending on the age of the restored stand, prevailing hydrological and geomorphological conditions, and the latitude.

IMTA and seagrass restoration

Seagrasses provide a wide range of ecological services, including carbon and nutrient cycling, sediment stabilization, biodiversity conservation, and secondary production (Orth et al. 2006; Saenger et al. 2013). However, seagrass losses have accelerated as globally 33 000 km2 of seagrass meadows were lost owing to direct and indirect human impacts over the last two decades (Walker et al. 2006). Destructive fishing is one of the key reasons for loss of seagrasses. Trawl fishing has devastating effects on seagrasses as bottom trawling destroys the shoots and rhizomes of seagrasses (Murray et al. 2011).

There is a huge potential for seaweed culture in IMTA (Barrington et al. 2009; Troell et al. 2009; Chopin et al. 2012). Seaweed can grow in complex environmental conditions and tolerate changes in salinity and temperature. Seaweed culture in IMTA can play an important role in reducing CO2 emissions (Chung et al. 2011). In addition to the culture of seaweeds, IMTA could be placed in areas suited to seagrass colonization to protect against trawl fishing. In that case, IMTA may create an obstacle to destructive fishing which in turn would help to restore seagrasses that could enhance blue carbon sequestration (Greiner et al. 2013). Globally, seagrass meadows sequester blue carbon at a rate of 0.54–0.83 t ha−1 annually (Duarte et al. 2005; Siikamäki et al. 2012). If IMTA could help to restore about one-fourth of lost seagrass meadows (0.82 million ha), it could sequester between 0.44 and 0.68 million tons of blue carbon annually (Table 1). Moreover, seaweed culture in IMTA using other environmentally friendly methods (e.g., long-lines and rafts) could help to sequester more blue carbon globally.

Shellfish aquaculture

Shellfish culture in IMTA is environmentally friendly as shellfish are filter feeders consuming particulate matter and microorganisms. A variety of mollusks, including mussels and oysters, have been introduced in IMTA. Shellfish feed at a lower trophic level in IMTA and consequently consume particulate organic nutrients, including waste feed (Barrington et al. 2009; Troell et al. 2009; Chopin et al. 2012). In IMTA, shellfish can remove up to 54% of particulate nutrients (Reid et al. 2010).

Shellfish sequester blue carbon and act as a carbon sink (SARF 2012). Global mollusk production was estimated at 16.1 million tons in 2014 (FAO 2016). The CO2 sequestration rate by shells of mussels and oysters is 0.22 and 0.44 ton per ton of harvest,8 respectively (SARF 2012). At these rates, 16.1 million tons of mollusks could sequester 0.97–1.93 million tons of blue carbon annually. Global blue carbon sequestration could be increased through shellfish production in IMTA and other culture methods. With a total increase of 4.03 million tons in shellfish production globally (25% increase), it could sequester 0.24–0.48 million tons of additional blue carbon annually (Table 1).

Future prospects: opportunities and challenges

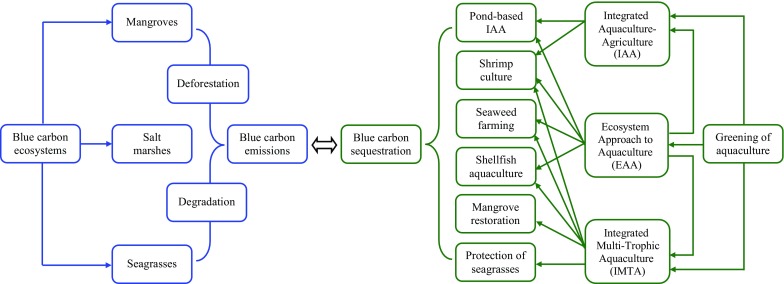

To tackle climate change, it is important to continue the greening of aquaculture and increase its role in sequestering blue carbon (Fig. 1). If one-fourth of degraded mangroves and seagrasses were restored by the greening of aquaculture, 25% of coastal ponds were converted to IAA and shellfish production increased by 25%, it could be possible to sequester 97 million tons of additional blue carbon annually (Table 1). This would be 1% of global annual carbon emissions that reached 9.73 billion tons (or 35.7 billion tons of CO2) in 2014 (Olivier et al. 2015). Despite this relatively low contribution, the greening of aquaculture to sequester blue carbon has some climate change mitigation potential. This could be a part of a “blue carbon initiative” to enhance resilience to climate change (UNEP 2011). Maintaining coastal ecosystems and expanding blue carbon sinks through the greening of aquaculture is a win–win strategy. Mangrove plantation and regeneration could help to increase resilience to climate change, including protection against coastal flooding, erosion, sea level rise, storm surges, and wave action (Alongi 2008; Huxham et al. 2010; Duarte et al. 2013). Restoration of seagrasses could also help to mitigate and adapt to the impacts of climate change (Fourqurean et al. 2012; Duarte et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

Blue carbon emissions from coastal ecosystems with potential for blue carbon sequestration through the greening of aquaculture

The greening of aquaculture could provide a wide range of socioeconomic and environmental benefits. There is an opportunity to improve the lives of people in coastal communities through the greening of aquaculture which could provide food, income, and livelihood opportunities. The greening of aquaculture could also provide economic growth through producing high-value seafood commodities for export. Moreover, restoration of mangroves and seagrasses could help to conserve aquatic biodiversity and fisheries production (Saenger et al. 2013).

Despite the potential benefits, the greening of aquaculture in coastal communities faces several challenges (Table 2). IAA may need to overcome water management problems, including freshwater scarcity and saltwater intrusion into coastal ponds. Effective blue (irrigation) and green (rain) water management could, however, help to increase food production as IAA produces “more crop per drop” (Rockström et al. 2009; Ahmed et al. 2014). Recycling of nutrients in pond-based IAA may limit the accumulation of carbon stocks in pond sediments. Accumulation of organic carbon in pond sediments promotes anaerobic conditions leading to microbial activities that may cause fish diseases. Microbial activities in anoxic pond sediments can result in a loss of soil carbon (Bunting and Pretty 2007). Endeavoring to use nutrient-rich pond mud as a fertilizer for terrestrial crop production could release GHG. Offshore IMTA is also not protected from a range of environmental problems, including water pollution, parasite transmission, and disease outbreaks. Close placement of different IMTA species can intensify pathogen exposure, and thus, pose health risks to consumers (Klinger and Naylor 2012). User conflicts over access to water and fisheries resources may also arise in the case of offshore IMTA. Community-based fisheries management can be an effective means to mobilize farming communities in the transition from inland to offshore areas for better access to water and enhanced water management (Khan et al. 2015). IMTA involving the translocation of shrimp culture for mangrove and seagrass restoration, seaweed cultivation, and shellfish production could face technical and environmental constraints. Competition from conventional aquaculture production may threaten the economic viability of such carbon-sensitive practices. These challenges must be addressed to realize the full potential of greening of aquaculture to sequester blue carbon.

Table 2.

Possible constraints to sequestering blue carbon through the greening of aquaculture

| Greening of aquaculture | Constraints |

|---|---|

| Pond-based IAA | IAA may face water management problems including freshwater scarcity and saltwater intrusion into coastal areas Prevailing pond management regimes adopted to recycle nutrients may prevent the accumulation of carbon sediments Removal of pond sediments to manure for terrestrial crop production may result in GHG emissions |

| Shrimp culture from mangroves to IMTA | Translocation of shrimp from mangroves to offshore IMTA may be difficult to restore mangroves due to changes in hydrological and environmental conditions Concerns for offshore IMTA in terms of environmental and bio-safety issues Profitability may be uncertain due to high cost associated with offshore IMTA |

| Seaweed culture in IMTA and seagrass restoration | Technical and environmental difficulties for restoration of seagrasses through IMTA Regimes to exclude fishers from IMTA and seagrass restoration areas may be difficult to establish Seaweed harvesting from IMTA may release blue carbon |

| Shellfish aquaculture | Harvesting of shellfish may cause eutrophication and GHG emissions Shellfish generally require depuration before sale which can result in GHG emissions Storage and cooking across product value chains can result in GHG emissions |

Conclusions

The greening of aquaculture is a promising mechanism to reduce blue carbon emissions. The greening of aquaculture can help to sequester blue carbon in coastal ecosystems which is a crucial aspect to mitigating climate change. However, the greening of aquaculture will require technical and financial assistance as well as institutional support to address several challenges. To realize wider benefits from blue carbon sequestration, all major stakeholders including international agencies, researchers, government and non-governmental organizations, and coastal communities should work together for the implementation of greening of aquaculture. Green payments may be required for reducing blue carbon emissions and maximizing sequestration (Gordon et al. 2011; Murray et al. 2011). To increase the participation of coastal communities in the greening of aquaculture, it will be necessary to increase their awareness through training programs and technical assistance. Social and environmental issues within coastal communities must also be identified and addressed to facilitate the successful adoption of IAA and IMTA. Intensive research is needed to better understand and optimize the process of greening aquaculture in terms of blue carbon sequestration and storage for climate change mitigation. Applied research on coastal ecosystem management through the greening of aquaculture also demands particular attention.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported through the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Germany. The study was a part of the first author’s research work under the Georg Forster Research Fellowship by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology, Bremen, Germany. The idea for this paper was generated after the first author attended the 3rd International Symposium on the Effects of Climate Change on the World’s Oceans, Santos, Brazil during 23–27 March 2015 as an invited speaker. Thanks to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea and the North Pacific Marine Science Organization for supporting attendance at the symposium. We thank three anonymous reviewers for insightful comments and suggestions. The views and opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors.

Biographies

Nesar Ahmed

is a Georg Forster Research Fellow supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation at the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Bremen, Germany. Prior to joining ZMT, he was a Fulbright Research Fellow at the School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, USA. He received his PhD from the Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling, UK through a Department for International Development (DFID) UK scholarship and won the Endeavour Research Fellowship of the Australian Government for Postdoctoral Research at Charles Darwin University, Australia and also received a Centre for International Cooperation and Development (CICOPS) Fellowship at the University of Pavia, Italy. He is also an Adjunct Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Water Management and Reuse, University of South Australia. His current research focuses on social–ecological aspects of coastal aquaculture in relation to climate change.

Stuart W. Bunting

is the founder of Bunting Aquaculture, Agriculture and Aquatic Resources Conservation Services, Suffolk, UK. He completed his PhD from the Institute of Aquaculture, University of Stirling, UK. He is committed to ensuring interactive participation in his research and has devised a process of integrated action planning to facilitate action research in support joint assessment and decision-making by stakeholders. He was recently engaged by The Crown Estate to complete carbon footprint assessments for UK marine aquaculture sector product value chains. This work covered halibut and salmon culture and mussel and oyster cultivation and included a stakeholder Delphi-based assessment of mitigation options and bioeconomic modeling of alternative mitigation strategies. His book entitled “Principles of Sustainable Aquaculture: Promoting Social, Economic and Environmental Resilience” was published by Routledge in 2013. He has over 20 years of research experience concerning aquatic resources management, carbon footprint and mitigation assessments, and sustainable aquaculture and fisheries development in Europe and Asia.

Marion Glaser

leads the Social–Ecological Systems Analysis Group at the Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Ecology (ZMT), Bremen, Germany. In her research, she develops and interfaces social science knowledge to support the development of sustainable human–nature relations. Drawing on long-term academic and participatory action research into regional development in Bangladesh, Belize, Brazil, and Indonesia, she is now also actively engaged in the creation of international knowledge and science-policy networks that respond to the grand challenges of global sustainability research. Her current work explores the potential for transdisciplinary site- and ecosystem-specific collaborations that elucidate social–ecological connectivity and advance cross-scale multi-level analysis of the social drivers of social–ecological change.

Mark S. Flaherty

is a Professor in the Department of Geography, University of Victoria, Canada. His research focuses on social and environmental impacts of the development of coastal aquaculture on communities in tropical developing countries. He was a Co-director of the Southern Oceans Education and Development project: Building Sustainable Aquaculture in Mozambique (2007–2013). He presently sits on the Board of Directors of the Pacific SEA-Lab Research Society, which is a non-profit organization that is dedicated to the Development of Sustainable Ecological Aquaculture (SEA) systems. He is a Co-founder and Director of Tropical Initiatives for the Coastal Aquaculture Research and Training (CART) Network. CART is playing a key role in the Canadian Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture Network which is being funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada.

James S. Diana

is a Professor of aquaculture and fisheries at the School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, USA. He is also Director of the Michigan Sea Grant Program, funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. His research focuses on aquatic animals and their interactions with the environment and interfaces between aquaculture practices and environmental impacts and seeks to find solutions for more sustainable aquaculture production in the future. This is expressed in two major research areas: sustainable aquaculture and its role in feeding the world, and the ecology of natural fish populations, particularly in the Great Lakes region. His teaching is in aquatic sciences, in particular, courses in Ecology and Biology of Fishes and Sustainable Aquaculture. In addition, he supervises research of a large number of graduate students in aquatic sciences.

Footnotes

A carbon sink is a natural or artificial reservoir or pool that accumulates and stores some carbon-containing chemical compound for an indefinite period. Sink is also a process, activity, or mechanism that removes a GHG from the atmosphere.

Capture is the separation of CO2 from other gases. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is a process consisting of separation of CO2 from its sources, transport to a storage location, and long-term isolation from the atmosphere.

Carbon sequestration is the process involved in carbon capture and the long-term storage of atmospheric CO2. Sequestration is the removal of atmospheric CO2 through biological (photosynthesis) or geological (storages in underground reservoirs) processes.

Seaweeds must not be confused with seagrasses as seaweeds are marine macroalgae, while seagrasses are vascular plants. Seaweeds can be either wild or aquaculture crops, while it is challenging to restore seagrass beds owing to difficulty in transplanting seedlings.

Globally, the annual loss rate was 1–2% for tidal marshes, 0.7–3% for mangroves, and 0.4–2.6% for seagrasses (Pendleton et al. 2012).

Carbon accumulation in agriculturally eutrophic impoundments is high as they receive allochthonous carbon through erosion, autochthonous carbon through nutrient-driven primary productivity, and exhibit very high rates of preservation due to nearly continuous sediment anoxia (Downing et al. 2008).

In 2004, there were 11.08 million ha of aquaculture ponds worldwide (Verdegem and Bosma 2009) and the current global aquaculture area was estimated based on the changes in total aquaculture production.

Equivalent to 0.06 and 0.12 ton of carbon sequestration per ton of mussels and oysters harvested, respectively, as one ton of carbon is equal to 3.67 tons of CO2. These figures do not take into account CO2-eq emissions generated as a consequence of cultivation practices or during other phases in the product value chain which will ultimately dictate the net amount of CO2-eq sequestered or emitted as a consequence shellfish consumption.

Contributor Information

Nesar Ahmed, Email: nesar.ahmed@zmt-bremen.de, Email: nesar.ahmed@unisa.edu.au.

Stuart W. Bunting, Email: stuartwbunting@gmail.com

Marion Glaser, Email: marion.glaser@leibniz-zmt.de.

Mark S. Flaherty, Email: flaherty@office.geog.uvic.ca

James S. Diana, Email: jimd@umich.edu

References

- Adhikari S, Lal R, Sahu BC. Carbon sequestration in the bottom sediments of aquaculture ponds of Orissa, India. Ecological Engineering. 2012;47:198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Toufique KA. Greening the blue revolution of small-scale freshwater aquaculture in Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Aquaculture Research. 2015;46:2305–2322. doi: 10.1111/are.12390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Glaser M. Coastal aquaculture, mangrove deforestation and blue carbon emissions: Is REDD+ a solution? Marine Policy. 2016;66:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2016.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N, Ward JD, Saint CP. Can integrated aquaculture–agriculture (IAA) produce “more crop per drop”? Food Security. 2014;6:767–779. doi: 10.1007/s12571-014-0394-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi DM. Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 2008;76:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2007.08.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alongi DM. Carbon cycling and storage in mangrove forests. Annual Review of Marine Science. 2014;6:195–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010213-135020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington, K., T. Chopin, and S. Robinson. 2009. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) in marine temperate waters. In Integrated mariculture: A global review, ed. D. Soto. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper No. 529: 7–46.

- Barrington K, Ridler N, Chopin T, Robinson S, Robinson B. Social aspects of the sustainability of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Aquaculture International. 2010;18:201–211. doi: 10.1007/s10499-008-9236-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillon S, Borges AV, Castañeda-Moya E, Diele K, Dittmar T, Duke NC, Kristensen E, Lee SY, et al. Mangrove production and carbon sinks: A revision of global budget estimates. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2008;22:GB2013. doi: 10.1029/2007GB003052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CE, Tucker CS. Pond aquaculture water quality management. Boston: Kluwer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CE, Wood CW, Chaney PL, Queiroz JF. Role of aquaculture pond sediments in sequestration of annual global carbon emissions. Environmental Pollution. 2010;158:2537–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting SW, Pretty J. Aquaculture development and global carbon budgets: Emissions, sequestration and management options. Essex: Centre for Environment and Society, University of Essex; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Burch D, Lyons K, Lawrence G. What do we mean by ‘green’? Consumers, agriculture and the food industry. In: Lockie S, Pritchard B, editors. Consuming foods, sustaining environments. Brisbane: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chopin T. Progression of the integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) concept and upscaling of IMTA systems towards commercialization. Aquaculture Europe. 2011;36:5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chopin T, Cooper JA, Reid G, Cross S, Moore C. Open-water integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: Environmental biomitigation and economic diversification of feed aquaculture by extractive aquaculture. Reviews in Aquaculture. 2012;4:209–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-5131.2012.01074.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung IK, Beardall J, Mehta S, Sahoo D, Stojkovic S. Using marine macroalgae for carbon sequestration: A critical appraisal. Journal of Applied Phycology. 2011;23:877–886. doi: 10.1007/s10811-010-9604-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chung IK, Oak JH, Lee JA, Shin JA, Kim JG, Park K-S. Installing kelp forests/seaweed beds for mitigation and adaptation against global warming: Korean project overview. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2013;70:1038–1044. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fss206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Pierce BA. Ecological aquaculture: The evolution of the blue revolution. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Pierce, B.A. 2008. An ecosystem approach to marine aquaculture: A global review. In Building an ecosystem approach to aquaculture, ed. D. Soto, J. Aguilar-Manjarrez, and N. Hishamunda. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Proceedings No. 14: 81–115.

- Dey MM, Paraguas FJ, Kambewa P, Pemsl DE. The impact of integrated aquaculture–agriculture on small-scale farms in Southern Malawi. Agricultural Economics. 2010;41:67–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00426.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diana JS, Egna HS, Chopin T, Peterson MS, Cao L, Pomeroy R, Verdegem M, Slack WT, et al. Responsible aquaculture in 2050: Valuing local conditions and human innovations will be key to success. BioScience. 2013;63:255–262. doi: 10.1525/bio.2013.63.4.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donato DC, Kauffman JB, Murdiyarso D, Kurnianto S, Stidham M, Kanninen M. Mangroves among the most carbon-rich forests in the tropics. Nature Geoscience. 2011;4:293–297. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downing JA, Cole JJ, Middelburg JJ, Striegl RG, Duarte CM, Kortelainen P, Prairie YT, Laube KA. Sediment organic carbon burial in agriculturally eutrophic impoundments over the last century. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 2008;22:GB1018. doi: 10.1029/2006GB002854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte CM, Middelburg JJ, Caraco N. Major role of marine vegetation on the oceanic carbon cycle. Biogeosciences. 2005;1:173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte CM, Losada IJ, Hendriks IE, Mazarrasa I, Marbà N. The role of coastal plant communities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Nature Climate Change. 2013;3:961–968. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NC, Meynecke J-O, Dittmann S, Ellison AM, Anger K, Berger U, Cannicci S, Diele K, et al. A world without mangroves? Science. 2007;317:41–42. doi: 10.1126/science.317.5834.41b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO . The world’s mangroves 1980–2005. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . The state of world fisheries and aquaculture: Contributing to food security and nutrition for all. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fourqurean JW, Duarte CM, Kennedy H, Marbà N, Holmer M, Mateo MA, Apostolaki ET, Kendrick GA, et al. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nature Geoscience. 2012;5:505–509. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon D, Murray BC, Pendleton L, Victor B. Financing options for blue carbon: Opportunities and lessons from the REDD+ experience. Durham, NC: Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, Duke University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner JT, McGlathery KJ, Gunnell J, McKee BA. Seagrass restoration enhances “blue carbon” sequestration in coastal waters. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72469. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SJ, Delaporte A, Phillips MJ, Beveridge M, O’Keefe M. Blue frontiers: Managing the environmental costs of aquaculture. Penang: The WorldFish Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halwart, M., and M.V. Gupta (eds.). 2004. Culture of fish in rice fields. Penang: FAO and The WorldFish Center.

- Hanson A, Cui H, Zou L, Clarke S, Muldoon G, Potts J, Zhang H. Greening China’s fish and fish products market supply chains. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hersoug B. The greening of Norwegian salmon production. Maritime Studies. 2015;14:16. doi: 10.1186/s40152-015-0034-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill R, Bellgrove A, Macreadie PI, Petrou K, Beardall J, Steven A, Ralph PJ. Can macroalgae contribute to blue carbon? An Australian perspective. Limnology and Oceanography. 2015;60:1689–1706. doi: 10.1002/lno.10128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huxham M, Kumara MP, Jayatissa LP, Krauss KW, Kairo J, Langat J, Mencuccini M, Skov MW, et al. Intra- and interspecific facilitation in mangroves may increase resilience to climate change threats. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2010;365:2127–2135. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . Climate change 2007: Assessment report. Valencia: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC . Climate change 2014: Synthesis report—summary for policymakers. Valencia: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khan AKMF, Mustafa MG, Naser MN. Effective supervision of inland capture fisheries of Bangladesh and its hurdles in managing the resources. Bandung: Journal of the Global South. 2015;2:17. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger D, Naylor R. Searching for solutions in aquaculture: Charting a sustainable course. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 2012;37:247–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-021111-161531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knowler, D. 2008. Economic implications of an ecosystem approach to aquaculture. In Building an ecosystem approach to aquaculture, ed. D. Soto, J. Aguilar-Manjarrez, and N. Hishamunda. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Proceedings No. 14: 47–65.

- Locatelli T, Binet T, Kairo JG, King L, Madden S, Patenaude G, Upton C, Huxham M. Turning the tide: How blue carbon and payments for ecosystem services (PES) might help save mangrove forests. Ambio. 2014;43:981–995. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcleod E, Chmura GL, Bouillon S, Salm R, Björk M, Duarte CM, Lovelock CE, Schlesinger WH, et al. A blueprint for blue carbon: Toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2011;9:552–560. doi: 10.1890/110004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moss SM, Arce SM, Argue BJ, Otoshi CA, Calderon FRO, Tacon AGJ. Greening of the blue revolution: Efforts toward environmentally responsible shrimp culture. Hawaii: The Oceanic Institute; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murray BC, Pendleton L, Jenkins WA, Sifleet S. Green payments for blue carbon: Economic incentives for protecting threatened coastal habitats. Durham, NC: Nicholas Institute, Duke University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nellemann C, Corcoran E, Duarte CM, Valdés L, De Young C, Fonseca L, Grimsditch G, editors. Blue carbon: The role of healthy oceans in binding carbon—a rapid response assessment. Norway: GRID-Arendal, United Nations Environment Programme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Neori A, Troell M, Chopin T, Yarish C, Critchley A, Buschmann AH. The need for a balanced ecosystem approach to blue revolution aquaculture. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 2007;49:36–43. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.49.3.36-43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier JGJ, Janssens-Maenhout G, Muntean M, Peters JAHW. Trends in global CO2 emissions: 2015 Report. The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency, and Joint Research Centre, European Commission; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Orth RJ, Carruthers TJB, Dennison WC, Duarte CM, Fourqurean JW, Heck KL, Jr, Hughes AR, Kendrick GA, et al. A global crisis for seagrass ecosystems. BioScience. 2006;56:987–996. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)56[987:AGCFSE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pant J, Demaine H, Edwards P. Assessment of the aquaculture subsystem in integrated agriculture–aquaculture systems in Northeast Thailand. Aquaculture Research. 2004;35:289–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2004.01014.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pendleton L, Donato DC, Murray BC, Crooks S, Jenkins WA, Sifleet S, Craft C, Fourqurean JW, et al. Estimating global “blue carbon” emissions from conversion and degradation of vegetated coastal ecosystems. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43542. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prein M. Integration of aquaculture into crop–animal systems in Asia. Agricultural Systems. 2002;71:127–146. doi: 10.1016/S0308-521X(01)00040-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S, Venugopalan VP, van der Velde G, Jenner HA. Greening of the coasts: A review of the Perna viridis success story. Aquatic Ecology. 2006;40:273–297. doi: 10.1007/s10452-006-9032-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GK, Liutkus M, Bennett A, Robinson SMC, MacDonald B, Page F. Absorption efficiency of blue mussels (Mytilus edulis and M. trossulus) feeding on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) feed and fecal particulates: Implications for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. Aquaculture. 2010;299:165–169. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockström J, Falkenmark M, Karlberg L, Hoff H, Rost S, Gerten D. Future water availability for global food production: The potential of green water for increasing resilience to global change. Water Resources Research. 2009;45:W00A12. doi: 10.1029/2007WR006767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saenger P, Gartside D, Funge-Smith S. A review of mangrove and seagrass ecosystems and their linkage to fisheries and fisheries management. Bangkok: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SARF . Carbon footprint of scottish suspended mussels and intertidal oysters. Scotland: Scottish Aquaculture Research Forum; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sayre R. Microalgae: The potential for carbon capture. BioScience. 2010;60:722–727. doi: 10.1525/bio.2010.60.9.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda-Machado M, Aguilar-González B. Significance of blue carbon in ecological aquaculture in the context of interrelated issues: A case study of Costa Rica. In: Mustafa S, Shapawi R, editors. Aquaculture ecosystems: Adaptability and sustainability. Chichester: Wiley; 2015. pp. 182–242. [Google Scholar]

- Serfling S. Good aquaculture practices to reduce the use of chemotherapeutic agents, minimize bacterial resistance, and control product quality. Bulletin of Fisheries Research Agency. 2015;40:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Siikamäki J, Sanchirico JN, Jardine S, McLaughlin D, Morris DF. Blue carbon: Global options for reducing emissions from the degradation and development of coastal ecosystems. Washington, DC: Resources for the Future; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Siikamäki J, Sanchirico JN, Jardine S, McLaughlin D, Morris D. Blue carbon: Coastal ecosystems, their carbon storage, and potential for reducing emissions. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 2013;55:14–29. doi: 10.1080/00139157.2013.843981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, S. 2011. The blue food revolution: Making aquaculture a sustainable food source. Scientific American February: 54–61. [PubMed]

- Soto, D., J. Aguilar-Manjarrez, C. Brugère, D. Angel, C. Bailey, K. Black, P. Edwards, B. Costa-Pierce, et al. 2008. Applying an ecosystem-based approach to aquaculture: Principles, scales and some management measures. In Building an ecosystem approach to aquaculture, ed. D. Soto, J. Aguilar-Manjarrez, and N. Hishamunda. Rome: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Proceedings No. 14: 15–35.

- Spalding MD, Kainuma M, Collins L. World atlas of mangroves. London: Earthscan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stepien CC, Pfister CA, Wootton JT. Functional traits for carbon access in macrophytes. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159062. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troell M, Joyce A, Chopin T, Neori A, Buschmann AH, Fang J-G. Ecological engineering in aquaculture—Potential for integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) in marine offshore systems. Aquaculture. 2009;297:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2009.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNEP . Blue carbon initiative: The role of coastal ecosystems in climate change mitigation. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP . The importance of mangroves to people: A call to action. Cambridge: World Conservation Monitoring Centre, United Nations Environment Programme; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Valiela I, Bowen JL, York JK. Mangrove forests: One of the world’s threatened major tropical environments. BioScience. 2001;51:807–815. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0807:MFOOTW]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verdegem MCJ, Bosma RH. Water withdrawal for brackish and inland aquaculture, and options to produce more fish in ponds with present water use. Water Policy. 2009;11:52–68. doi: 10.2166/wp.2009.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DI, Kendrick GA, McComb AJ. Decline and recovery of seagrass ecosystems—The dynamics of change. In: Larkum AWD, Orth RJ, Duarte CM, editors. Seagrasses: Biology, ecology and conservation. Dordrecht: Springer; 2006. pp. 551–565. [Google Scholar]

- Waycott M, Duarte CM, Carruthers TJB, Orth RJ, Dennison WC, Olyarnik S, Calladine A, Fourqurean JW, et al. Accelerating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:12377–12381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905620106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, O’Neill B, Tzankova Z. At a crossroads: Will aquaculture fulfill the promise of the blue revolution? Washington, DC: SeaWeb Aquaculture Clearing House; 2004. [Google Scholar]