Abstract

Objectives

Approximately 1 % of all malignant solid tumours of the head and neck area are metastases from primary tumours beneath the clavicles. The aim of this study was to analyse the distribution of primary tumours since meta-analyses might have been biased due to the usually extraordinary character of case reports.

Materials and Methods

All patient files from 1970 to 2012 from the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery unit at a University Hospital were analysed regarding the existence of metastases to the head and neck area from distant primaries.

Results

Of the seventy-three patients 18 had breast cancers (25 %), 9 melanomas (12 %), 8 tumours of the kidneys and 8 of the lungs (each 12 %), 3 colon cancers (6 %), 2 prostate cancers (3 %), 2 Ewing sarcomas (3 %), and 1 each of liposarcoma, esophagus, rectum, hepatocellular carcinoma, vulva, ovarian and testicular cancer. In 15 cases, a cancer of unknown primary was diagnosed. In 28 cases the metastasis was the initial sign of the malignant disease. Skeletal metastasis occurred in 37 cases and a soft tissue metastasis in 36 patients.

Conclusion

The different primaries seem to metastasize in different frequencies to the head and neck area. The relatively common prostate cancer rarely seems to produce metastases in the head and neck area compared to cancers arising in the kidneys. In case of a malignant tumour of unknown primary, osseous metastases most often are caused by breast or lung cancer or renal cell carcinoma. Soft tissue metastases are most often caused by breast cancer.

Keywords: Metastasis, Head and neck, Tumour, Cancer

Introduction

Malignancies of the head and neck region usually arise locally as primary tumours [1]. Approximately 0.002–2 % of all malignancies to the oral and maxillofacial region (OMFR) are metastases from distant primary tumours arising underneath the upper thoracic aperture [2–4].

Hematologic and non-lymphatic spread is postulated for most metastases to the OMFR, in which the portal hematogenous way is the most likely. An exclusive spread via this route would not explain the frequent lack of metastasis to the lungs and why some authors see the valveless vertebral venous plexus as an alternative way for tumour cells to reach the OMFR [5].

Likely regions for metastasis are osseous structures, especially the mandible and its molar and premolar region. Metastasis to the soft tissues is rare and most often occurs in the gingiva. In general the primary tumour is known before detection of the supraclavicular metastasis (SCM) [3]. In about one-third of all patients, the metastasis was the initial sign of the malignant disease, and some of these cases are defined as a cancer of unknown primary (CUP) if there is failure in its detection [3].

Typical primary tumours causing SCM are breast, lung, kidney, prostate, uterus, stomach, and colon cancer. Some of the primary tumours are disproportionally more often associated with SCM regarding their over-all prevalence; this can be explained by their biological behaviour with metastatic spread in early tumour stages [3].

It is interesting that there is a great variability between the mostly smaller case series published by the different authors from different countries regarding the distribution of the primary tumours and the site of the metastasis. The differences in the distribution of the primary tumours might be due to different prevalences for the relevant tumours in the different countries. The more frequent occurrence of gingival lesions in developing countries compared to developed countries is explained by the poorer oral hygiene and therefore higher prevalence of oral inflammation that might contribute to the manifestation of SCM in the oral soft tissues [3].

Unfortunately clinical and radiologic signs are not specific, so that anamnesis and a histological analysis are necessary to find the accurate diagnosis [3].

Less than 1000 cases of SCM from distant primary tumours have been reported, and most of these are case reports [3].

The aim of this study was to analyse the distribution of supraclavicular metastases from distant primary tumours regarding the type of primary tumour as well as the metastasis site. Since most of the described cases are case reports, a meta-analysis might be biased due to the extraordinary character of most case reports.

Materials and Methods

To find all patients with a supraclavicular metastasis from a primary tumour located beneath the clavicle and patients with a CUP, all accessible patient data files were reviewed from 1971 to 2012. Data files as of 1971 were accessible. Since the year 2000, all patients have had digital files. All files before 2000 were checked manually for the relevant diseases in the surgical reports, any letters sent to other attending physicians and histological reports. The digital data files were searched with search terms: metastasis, carcinoma, cancer, cancer of unknown primary, tumour, sarcoma, breast, melanoma, skin cancer, NHL, lymphoma, b cell and t-cell. By using unspecific search terms such as metastasis, carcinoma and cancer the authors wanted to find as many patients as possible.

The inclusion criteria were the existence and the histological verification of a metastasis of a distant tumour or a CUP. All patients with CUP were referred to the ENT department for further diagnosis such as panendoscopy, PET, and potential tonsillectomy. Exclusion criteria were metastasis of supraclavicular primary tumours such as metastases from the thyroid gland, lymphomas and other haematologic diseases and patients with systemic spread of the malignant tumor and obvious reason for the tumor in the head and neck area. In addition patient cases without histological verification were excluded.

Collected data were: epidemiologic data, the order of occurrence of the primary tumour and the metastasis, the site of metastasis, symptoms and therapy.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student’s t test, the Chi square test and the exact Fisher’s test. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Fifty-eight patients had a distant metastasis to the head and neck region and an additional 15 patients had a cancer of unknown primary (CUP). The histological TNM of the primary tumor after therapy was not available.

The distribution of the different primary tumours is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of the metastases

| Primary tumour | n | F (n) | M (n) | Age at primary tumour | Age at metastasis | Bone metastasis | Soft tissue metastasis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN | SG | C | S | FM | |||||||

| Breast cancer | 18 | 18 | 0 | 50.5 | 58.2 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Melanoma | 9 | 0 | 9 | 59.7 | 63.9 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Lung cancer | 8 | 2 | 6 | 58.8 | 59.3 | 7 | 1 | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 8 | 3 | 5 | 58.6 | 60.4 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Colon carcinoma | 4 | 1 | 2 | 69.9 | 73.0 | 3 | |||||

| Prostate cancer | 2 | 0 | 2 | 69.2 | 72.0 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Ewing Sarcoma | 2 | 0 | 2 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 2 | |||||

| Liposarcoma | 1 | 0 | 1 | 65.5 | 67.2 | 1 | |||||

| Esophagus carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 0 | 56.4 | 56.4 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Stomach cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 53.0 | 54.2 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Rectum cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 67.0 | 74.8 | 1 | |||||

| HCC | 1 | 0 | 1 | 73.0 | 73.0 | 1 | |||||

| Vulva cancer | 1 | 1 | 0 | 52.2 | 56.8 | 1 | |||||

| Ovarial cancer | 1 | 1 | 0 | 71.5 | 71.7 | 1 | |||||

| Testis cancer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 29.0 | 30.7 | 1 | |||||

| CUP | 15 | 5 | 10 | – | 55.4 | 2 | 13 | ||||

N number of patients, F female, M male, LN lymph node, SG submandibular gland, C cheek, S skin, FM floor of the mouth

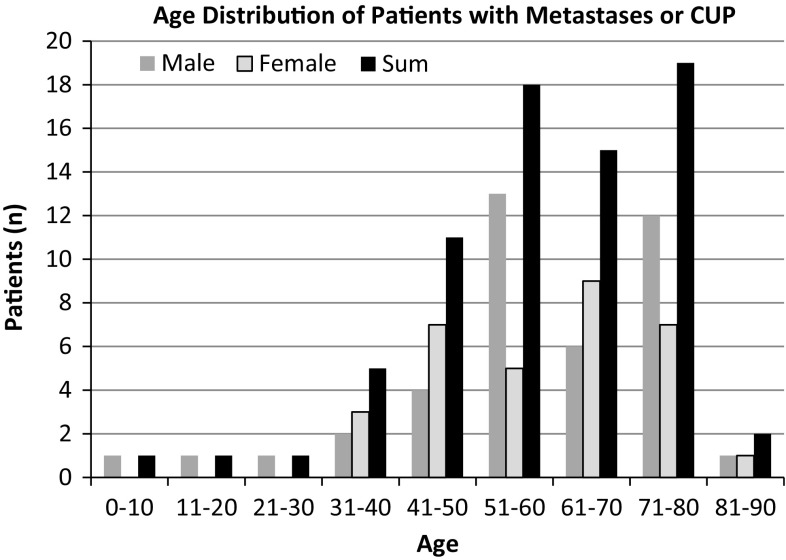

The average age at the time of diagnosis of the primary disease was 56 years [15 years SD; men: 56 years (17 years SD); women 56 years (13 years SD); p = 0.58]. At the age of detection of the metastasis (Fig. 1), the average age for all 73 patients was 59 years [16 years SD; men 58 years (17 years SD); women 60 years (14 years SD); p = 0.98].

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of patients with a CUP or a metastasis in the head and neck area from a subclavian primary tumour. The average age for the CUP patients was 56 years ± 13. The male patients had an average age of 52 years ± 13 and the female patients an average age of 62 years ± 12

In 38 patients the metastasis occurred on the left hand side and in 28 patients on the right hand side. In the remaining seven patients the metastases occurred on both sides.

In 25 out of the 73 cases (34 %) the occurrence of the supraclavicular metastasis was the initial sign of the malignant disease: breast cancer patients (n = 2), patients with lung cancer (n = 5), renal cell carcinoma (n = 2), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 1) and 15 patients (21 %) with a CUP. On an average the primary tumour was found after 25 days (range 3–150) in the 10 patients (14 %) with no CUP. In three patients the metastasis and the primary tumour were detected on the same day (breast cancer, renal cell cancer and Ewing sarcoma). In 44 (60 %) out of the 73 patients the supraclavicular metastasis occurred after the primary tumour was already known. In these patients the average time span between diagnosis of the primary tumour and the metastasis was 62 months (minimum: 1 day lung cancer, maximum: 24 years in a patient with breast cancer). In one case no data could be found regarding the diagnosis date for the primary tumour (breast cancer patient).

Thirty-three patients had one metastasis in osseous structures, 30 patients had one metastasis in the soft tissues, and 10 patients had more than one metastasis. In all 10 patients the metastases occurred either primarily in osseous structures (4 patients) or in the soft tissues (6 patients).

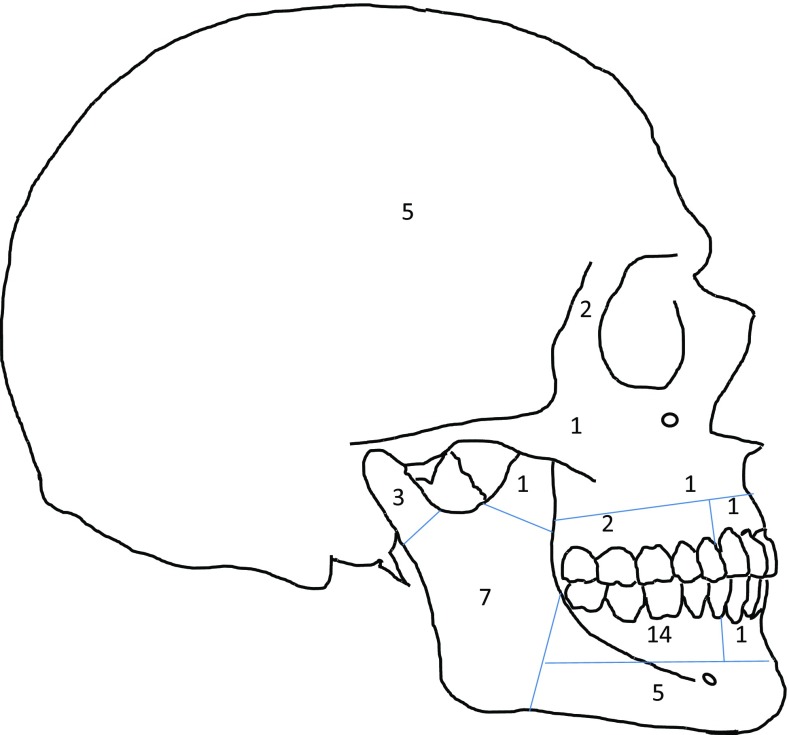

Forty-three metastases were located in osseous structures (Fig. 2): mandible (n = 29, 67 %), the maxilla (n = 4, 9 %), of which one case affected the maxillary sinus, temporomandibular joint and affected the joint socket of the posterior maxilla (n = 2, 5 %), the calvaria (n = 5, 12 %), zygomatic bone (n = 1, 2 %) and the orbit (n = 2, 5 %). Only one side of the head was affected in 36 cases, in three cases the metastasis involved both sides and in three cases the exact position could not be determined retrospectively. Breast and lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma were the most frequent tumours causing osseous metastases (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of skeletal metastases to the head and neck area from distant primaries

Forty-two metastases were located in the soft tissues in 36 patients: lymph nodes (n = 34), salivary glands (parotid gland: n = 3; submandibular gland: n = 1), floor of the mouth (n = 1), buccal mucosal membrane (n = 1), skin (n = 2). Breast cancer and melanoma were the most frequent tumours with soft tissue metastases to the head and neck area (Table 1).

The most common symptoms mentioned by the patients were swelling (n = 53, 73 %), pain (n = 28, 38 %), paresthesia (n = 16, 22 %), ulcer (n = 5, 7 %), reddish colour (n = 5, 7 %), pathologic fracture (n = 4, 5 %) and lockjaw (n = 4, 5 %); bleeding, loss of appetite and weight, tooth loosening, and smell were present in two patients each.

The therapy consisted of operative resection in combination with chemo- and radiotherapy. The exact treatment is not known in three patients (breast cancer). In 27 no further surgery was performed; the remaining 43 had a surgical excision of the metastasis, and in 31 cases further therapy such as chemotherapy or radiation took place. The 27 patients with no additional surgery received palliative treatment or declined any further treatment other than pain medication.

Thirty-eight (52 %) out of the 73 patients had additional metastases (n = 71) that were not located in the OMFR. In 35 cases (48 %) these metastases were not known before presenting at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Among the 38 patients, 18 had one more detectable metastasis while the remaining 20 patients had two or more metastases. Nine out of 18 patients with breast cancer, 7 out of 8 patients with renal cell carcinoma, 6 out of 8 with lung cancer, 4 out of 9 with melanoma, 2 out of 3 with colon cancer, 3 out of 15 with a CUP, 1 out of 2 with prostate cancer or Ewing sarcoma and one each with testicular, stomach, hepatocellular or esophagus cancer had further metastases. Thirty metastases were located in the skeletal system and 41 in the soft tissues.

Discussion

This study describes one of the biggest patient collectives worldwide with supraclavicular metastases from subclavian primary tumours. As of the end of 2013, only six studies report more than 20 genuine patients (Table 2). A systematic literature review analysing all publications in English or Chinese up to 2007 by a Chinese research group found only five articles with more than 20 patients and another 4 with more than 10 patients. Most articles are case reports, e.g. in the review more than 400 single case reports were analysed [3].

Table 2.

Publications that were not exclusively reviewed and had more than 20 patients

| 2014 | 2014 | 2013 | 2011 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2006 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Germany | USA | Canada | Germany | Germany | Netherlands | USA | Review |

| Reference | Present study | McClure [12] | Daley [13] | Thiele [14] | Friedrich [15] | Seoane [16] | D’Silva [17] | Shen [3] |

| Cases | 58 | 26 ➔ 25 | 38 ➔ 27 | 52 ➔ 41 | 92 ➔ 56 | 39 ➔ 32 | 114 ➔ 70 | 763 ➔ 719 |

| Diseases | Breast 18 | Lung 10 | Prostate 8 | Lung 12 | Breast 18 | Breast 8 | Breast 29 | Lung 142 |

| Melanoma 9 | Breast 6 | Lung 7 | Melanoma 9 | Lung 11 | Kidney 8 | Lung 15 | Breast 107 | |

| Kidney 8 | Colon 3 | Breast 5 | Breast 8 | Kidney 8 | Lung 8 | MRS 11 | Kidney 96 | |

| Lung 8 | Prostate 2 | Kidney 3 | Kidney 4 | Colorectal 8 | Prostate 3 | Colorectal 8 | Liver 53 | |

| Colon 3 | Leiomyosarcoma 2 | Colon 2 | Liver 2 | Melanoma 5 | Colon 2 | Kidney 3 | Prostate 47 | |

| Prostate 2 | Liver 2 | Colon 2 | Prostate 2 | Liver 2 | FRS 2 | Colorectal 46 | ||

| Ewing sarcoma 2 | Uterus 2 | Stomach 28 |

The line cases has two numbers. The first number is the one reported in the publication. The second number is the number of cases after the exclusion and inclusion criteria of the present study were applied, meaning that only subclavian primary tumours were included and hematologic tumours were excluded. The number behind each disease gives the number of patients. The diseases are ordered by the number of patients. The fields of the three most common diseases are filled in difference emphasis for better comparison: lung, breast, and kidney. All tumours with at least two cases are shown. Only for the literature review, a cut off was performed

MRS male reproductive system, FRS female reproductive system

Therefore due to the large proportion of case reports published in the international literature, there might be a bias in the distribution as there might be a tendency to report rare and spectacular cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rare incidence rates of frequent tumours for Germany for the year 2008

| Germany 2008 | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| Breast | 1.3 | 171.1 |

| Colorectal | 87.9 | 71.7 |

| Lung | 84.4 | 37.2 |

| Melanoma | 22.1 | 21.2 |

| Kidney | 22.3 | 13.3 |

| Prostate | 157.7 | |

| Liver | 13.1 | 3.2 |

Comparing this study’s results with the literature review dealing with metastases to the head and neck area from primary tumours underneath the clavicle [3] shows that this study’s patient population has significantly (p = 0.001) more patients with breast cancer (31 %; review: 15 %) and malignant melanoma (p < 0.001; 16 %; review: 3 %). The most frequent tumours in the review are lung cancer (19 %), breast cancer (15 %) and renal carcinomas (13 %). The most frequent tumours of this study are breast cancer (31 %), melanoma (16 %) and lung cancer (14 %).

Very interesting is the subclientel of 25 patients where the metastasis was the overall initial sign of the malignant disease. Next to the 15 CUP patients, where even due to further diagnosis and therapy the primary tumor stayed occult the most common cancers were lung, breast and renal cell carcinoma and therefore those tumors that have been described most often in the literature as well [3]. A possible conclusion could be that some tumors such as lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma spread in earlier stages to the head and neck region and others such as malignant melanoma in later stages.

In addition some tumours with a rather low prevalence rate cause metastases in the head and neck area more often than others with a higher prevalence. For example the non-age-adjusted incidence rate for lung cancer in Germany is 84.4 in 100,000 for men and 37.2 in 100,000 for women [6]. The numbers for tumours in the kidney are 22.3 and 13.3 in 100,000 for men and women respectively [6]. However, the rates of metastases do not correlate with these numbers since lung cancer and kidney tumours have the same number of metastases in the present study. Not taking the still very small patient numbers into account, another tumour-specific cause must be present. In advanced tumour stages, circulating tumour cells can be detected throughout the blood system but it is not completely understood at what point in time and where these cells form a metastasis [7]. A first theory for breast cancer was described as the seed and soil theory in 1889 by Paget [8]: The seed referring to the circulating tumour cell and the soil referring to a tumour-specific preferred site of metastases. In addition to the circulatory flow, the filter function of each organ and a genomic instability of the tumour, thereby possibly forming a heterogeneous population of circulating tumour cells, might be responsible for the distribution of metastases’ frequency and location [7, 9]. On the other side patients with lung cancer frequently become symptomatic early and due to the incurable characteristics of this disease secondary resections might be rare whereas in renal cancer the course of the disease is much longer and patients with a supraclavicular mass and potentially metastasis are more likely to be referred to an oral and maxillofacial department.

In the head and neck area, two additional anatomic characteristics might be of importance in the occurrence of metastasis: The thoracic duct that enters the venous system on the left-hand side of the neck at the junction of the subclavian and the internal jugular vein and the Batson venous plexus as a valveless venous plexus connecting pelvic, thoracic and deep vertebral plexus veins. Metastatic spread is possible via both systems, explaining the frequent lack of lung metastases in patients with metastases to the head and neck area since, via the normal route, the tumour-containing blood would first pass the lungs most probably causing metastases to the lung itself [10].

Although in most cases a cervical mass is the pathological symptom in the head and neck area [11], in some cases the primary stays occult. The finding of a supraclavicular metastasis associated to an infraclavicular cancer overall remains a rare event. In our patient cohort in most cases an underlying tumor was found, however in approximately 20 % of cases no primary site could be identified. With the increasing therapeutic options histologic confirmation of the tissue of origin is a key challenge to guide further treatment. Isolated supraclavicular masses can potentially be caused by distant primary tumours. Due to the unspecific symptoms, histological clarification is crucial.

Needless to say but a retrospective study like the present one comes along with limitations as well. Although using unspecific search terms such as metastasis, cancer and tumor it might be that not all patients that potentially could have been included were detected. Next to this there might be an additional bias since many patients with similar symptoms might be treated by the ENT department. Therefore a multidisciplinary and perhaps multicentre study would be desirable.

Conclusion

Different primaries metastasize in different frequencies to the head and neck area. In case of an osseous metastasis breast cancer, lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma are likely primary diseases; in case of soft tissue metastases breast cancer and melanoma are most frequent causes. CUP still is one of the most complex challenges regarding the treatment since the primary site of the tumor by definition is unknown. Therefore prevention is not really possible. A follow-up is crucial to detect further metastases as soon as possible to obtain the best prognosis for the patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.

Ethics Statement

A retrospective study was performed without any further consequences for the patient. According to this and the hospital laws of the individual states (Krankenhauslandesgesetz) no approval by the local ethics committee is necessary. The study was not sponsored.

References

- 1.Sagheb K, Sagheb K, Taylor KJ, Al-Nawas B, Walter C. Cervical metastases of squamous cell carcinoma of the maxilla: a retrospective study of 25 years. Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18(4):1221–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00784-013-1070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer I, Shklar G. Malignant tumors metastatic to mouth and jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1965;20:350–362. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(65)90167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen ML, Kang J, Wen YL, Ying WM, Yi J, Hua CG, et al. Metastatic tumors to the oral and maxillofacial region: a retrospective study of 19 cases in West China and review of the Chinese and English literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67(4):718–737. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Waal RI, Buter J, van der Waal I. Oral metastases: report of 24 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/S0266-4356(02)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batson OV. The function of the vertebral veins and their role in the spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940;112(1):138–149. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194007000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaatsch P, Spix C, Katalinic A, Hentschel S (2012) Robert Koch Institut Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten—Krebs in Deutschland 2007/2008

- 7.Scott J, Kuhn P, Anderson AR. Unifying metastasis—integrating intravasation, circulation and end-organ colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(7):445–446. doi: 10.1038/nrc3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. Lancet. 1889;1:571–573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)49915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta GP, Massague J. Cancer metastasis: building a framework. Cell. 2006;127(4):679–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aldridge T, Kusanale A, Colbert S, Brennan PA. Supraclavicular metastases from distant primaries: what is the role of the head and neck surgeon? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(4):288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balikci HH, Gurdal MM, Ozkul MH, Karakas M, Uvacin O, Kara N, et al. Neck masses: diagnostic analysis of 630 cases in Turkish population. Eur Arch Oto-rhino-laryngol. 2013;270(11):2953–2958. doi: 10.1007/s00405-013-2445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McClure SA, Movahed R, Salama A, Ord RA. Maxillofacial metastases: a retrospective review of one institution’s 15-year experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71(1):178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daley T, Darling MR. Metastases to the mouth and jaws: a contemporary Canadian experience. J Can Dent Assoc. 2011;77:b67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thiele OC, Freier K, Bacon C, Flechtenmacher C, Scherfler S, Seeberger R. Craniofacial metastases: a 20-year survey. J Cranio-maxillofac Surg. 2011;39(2):135–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedrich RE, Abadi M. Distant metastases and malignant cellular neoplasms encountered in the oral and maxillofacial region: analysis of 92 patients treated at a single institution. Anticancer Res. 2010;30(5):1843–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seoane J, Van der Waal I, Van der Waal RI, Cameselle-Teijeiro J, Anton I, Tardio A, et al. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity: a survival study with a special focus on gingival metastases. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(6):488–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Silva NJ, Summerlin DJ, Cordell KG, Abdelsayed RA, Tomich CE, Hanks CT, et al. Metastatic tumors in the jaws: a retrospective study of 114 cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(12):1667–1672. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]