INTRODUCTION

Borderline personality disorder (also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder) is a complex mental condition consisting of affective, cognitive-perceptual, anxiety, and stress-coping domains. Mental health professionals understand the problems in delivering required care and to a varying degree feel the pessimism with regard to its treatment. In this background, past two decades have witnessed various therapeutic attempts which over time have instilled much-needed optimism with the condition's treatment and prognosis.

One such therapeutic attempt is dialectical behavioral therapy (henceforth, DBT), which was introduced in the early 1990s by Linehan et al.[1] DBT has ever since garnered support of guidelines of many countries and has also been included in the American Managed Care system. While there are also other evidence-based therapies such as mentalization-based therapy, transference-focused therapy, schema-focused therapy, and dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy, none have found such popular appeal and encouragement by the professional guilds of psychiatry and psychology as did DBT. Hence, in this article, we will review the empirical evidence about DBT and examine whether its reputation equals its scientific basis.

WHAT IS DIALECTICAL BEHAVIORAL THERAPY?

DBT is an integrated psychotherapy comprising change techniques based on behavioral therapy on the one hand and acceptance techniques based on Zen Buddhism on the other hand. Both these techniques are used in a dialectic way to help patients handle and navigate through their complex affective and cognitive states.[2] The therapist has to move constantly between these two approaches, and to traverse this dialectic terrain, a personal practice of Zen Mindfulness and regular skills training is needed. Unlike cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) which has a near-complete integration of its component cognitive and behavioral theories, DBT lacks such a good fit between the behavioral and dialectic theories because of their radically different philosophical presuppositions; for example – the behavioral stance would like to change a “problem behavior” to an “adaptive behavior” while the other stance might suggest a nonjudgmental acceptance of the same behavior and thereby leading to a stalemate. Acceptance techniques are taught through the practice of various components of mindfulness. Dialectical theory presupposes that there is no one truth and therefore works toward an integration of multiple perspectives within a particular complex human problem.[3]

DBT model has four stages in the treatment of borderline personality. Each Stage (I–IV) has certain specific goals,[2] such as:

Reducing suicidal, therapy-interfering, and quality-of-life-interfering behaviors, and improving behavioral skills

Treating issues related with past trauma. For example, exposure techniques for posttraumatic stress disorder

Development of self-esteem, reclaiming ordinary happiness, and improving day-to-day behavioral skills

Development of capacity for optimum experiencing and finding a higher purpose.

Stage I may take anywhere from 3 to 12 months (usually, it takes at least a year[4]) and then the therapy moves onto Stages II–IV. The patient has to attend one individual therapy session and a group skills training session in a week and also has to do the regular homework such as diary records. There are two important components during the therapy which are central–regular group supervision for individual and group therapists, and 24/7 patient access to the therapist by telephone to handle emergencies.

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

DBT is the only available therapy which led to creation of a large research data in patients with borderline personality.[5] There are multiple studies done by Linehan over the last three decades. Independent researchers like Verheul et al.,[6] Clarkin et al.,[7] and McMain et al.[8] have also investigated using DBT.

Evidence in parasuicide (this term used in the studies by Linehan includes suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury)

Recent Cochrane review[9] reports that DBT when compared to treatment-as-usual (TAU) and community-treatment-by-experts (CTBE) shows no difference in the proportion of patients repeating self-harm or other outcomes such as suicidal ideation and depression, though frequency of repetition of self-harm reduces. Only one study[10] with weak methodology and small sample (n = 24) which compared DBT with client-centered therapy (which is not studied or used in borderline personality management) showed difference in impulsivity, suicidality, parasuicidality, and depression. Another recent article which reviewed the impact of treatment intensity on suicidal acts and depression[11] concluded that more intensive therapies (i.e., more than 100 h per year) are not superior to less intensive therapies (i.e., <100 h in a year). They have found that CBT for personality disorder with 30 h in a year is not inferior to DBT with 84 h or more in a year.

Evidence in other domains

There is a lack of evidence favoring DBT on core personality features such as interpersonal instability, chronic emptiness, and boredom and identity disturbance or associated symptoms such as depression, suicidal ideation, survival and coping beliefs, overall life satisfaction, work performance, and anxious rumination.[4,6,12] DBT was no different in reducing depression than any comparator, be it TAU, CTBE, or general psychiatric management (GPM). All therapies showed a reduction in depression over time.[11]

Except for three studies, which are discussed below, all the other studies have weak methodology and small sample sizes.[12,13] In the majority of studies, DBT was compared to TAU, which has its own problems such as:

It is difficult to know what treatment is given in TAU and it may change over a period of the study

TAU sessions are not documented or recorded and thereby adherence and competence ratings cannot be done

Patients in TAU comparatively get very less hours of treatment than in active structured treatments.

According to Chambless and Hollon,[14,15] psychological therapies have to fulfill five criteria to be called as “Empirically Supported Treatments.” These are superiority or equivalence to established/another treatment in studies with good methodological rigor (n = at least 30 per group); at least nine single-case design experiments showing efficacy; availability of manuals; clear specification of patient characteristics; and effects should be demonstrated by at least two independent teams. Ost argues in a review of study methodologies[13] that DBT randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have significantly less stringent research methodology than CBT studies and that they do not fulfill criteria for empirically supported treatments. A 2009 RCT with 180 samples and good methodology[8] suggests equivalence between DBT and GPM, thereby making DBT “probable-empirically supported treatment”

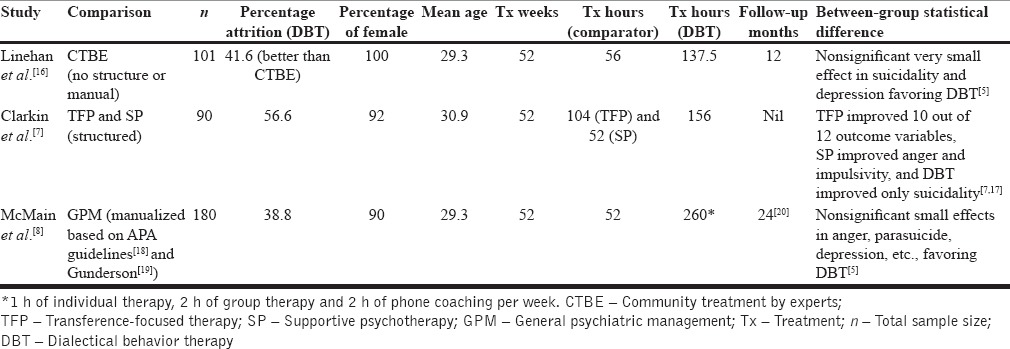

We will discuss only three studies which are rigorous and show us the empirical reality of DBT. Strengths of these studies being adequate power, investigators with a balance of theoretical allegiances (two studies[7,8]), and investigated by an independent group (two studies[7,8]) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of three well-designed and adequately powered studies investigating the comparative effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus other valid treatments

These studies show no statistically significant between-group differences for pathology-related outcomes, though there are marginal or very small effects in terms of suicidality, anger, depression, etc.[5] There is a significant difference in the treatment hours between DBT and comparators. Follow-up of Linehan's initial studies shows high dropout rate and loss of efficacy over time.[16,21] Researchers recommend an adequately powered head-to-head comparison using a rigorous methodology with a structured psychotherapy with good evidence base in borderline personality management such as transference-focused, schema-focused, or mentalization-based therapy instead of comparison with waiting list or TAU groups.[13] Reviewers have also observed that common team approach,[22] easy access, and intensive relationship focus in therapy and supervision of therapists by peers[4] are common features between psychodynamic therapies and DBT which have shown positive results in borderline personality management.

LIMITATIONS OF DIALECTICAL BEHAVIORAL THERAPY RESEARCH AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

DBT has a demanding model of therapy. A patient has to attend two separate sessions which include 1 h of individual therapy and 2 h of group skills training every week along with regular homework assignments over at least 1 year of treatment. Therapist has to be available 24/7 for providing emergency behavioral coaching, however rules can be laid down in this to protect therapist from burnout. It can be very costly because of multiple sessions and involvement of highly qualified therapists if it is not delivered through the public health-care system

All the DBT studies were of 1 year duration, however as pointed out earlier, Stage I itself many a times takes up to 1 year. Hence, we cannot suppose that studies have tested the whole therapy. Instead, they have tested the usefulness of just one, albeit an important stage of therapy. This might be the reason for the lack of evidence in domains of pathology other than parasuicide

DBT needs therapists who are highly qualified (many studies by Linehan had doctoral-level professionals) and who have to be under regular supervision by attending 2-h consultation team meeting every week for learning skills and supervision. This presents problems with dissemination and resource usage, especially in nonacademic centers, community, and resource-poor settings like India

Many reviewers including APA practice guidelines[13,23] suggest the need for studies by independent investigators. This is important because it ensures generalizability of findings and is an important criterion (criteria V) for empirically supported treatments

DBT has consistent evidence exclusively for reduction in frequency of suicide reattempts and also has evidence in those with eating disorders and substance use disorders; based on this, some[4,6] have suggested that either we have to change from DBT, after the reduction of suicidality, to another therapy which is more targeted at core features of borderline personality; or we have to assume that DBT is a specific therapy for patients (mainly female) with life-threatening impulse control disorders rather than borderline personality disorder per se

DBT when compared to other structured therapies does not fare well with regard to core features of borderline personality disorder except showing equivalence with regard to improvement in suicide attempts

Although a Cochrane review concludes that psychotherapies, in general, are effective in the management of borderline personality,[5] it is not altogether clear as to the role of medication in the management and there are no rigorous or adequately powered studies comparing medication and psychotherapy. This is important to consider because selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotic agents, and mood stabilizers are commonly used in clinical settings for the borderline personality management.

CONCLUSION

DBT has to be appreciated as its research has instilled the much-needed optimism into the management of borderline personality disorder management in the early 1990s. DBT has specific utility in addressing suicide attempts in borderline personality without being generally effective in the overall personality management. However, the review of its research and discussion of its limitations show that the empirical reality is very different from its reputation and popular exaggeration. There is a need for future studies to design adequately powered RCTs comparing it to other structured therapies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Linehan MM, Armstrong HE, Suarez A, Allmon D, Heard HL. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:1060–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810360024003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sadock B, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2009. p. 4884. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendit N. Reputation and science: Examining the effectiveness of DBT in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2014;22:144–8. doi: 10.1177/1039856213510959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blennerhassett RC, O’Raghallaigh JW. Dialectical behaviour therapy in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:278–80. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.4.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoffers JM, Völlm BA, Rücker G, Timmer A, Huband N, Lieb K. Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD005652. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verheul R, Van Den Bosch LM, Koeter MW, De Ridder MA, Stijnen T, Van Den Brink W. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–40. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clarkin JF, Levy KN, Lenzenweger MF, Kernberg OF. Evaluating three treatments for borderline personality disorder: A multiwave study. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:922–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMain SF, Links PS, Gnam WH, Guimond T, Cardish RJ, Korman L, et al. A randomized trial of dialectical behavior therapy versus general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1365–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Hazell P, et al. Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD012189. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner RM. Naturalistic evaluation of dialectical behavior therapy-oriented treatment for borderline personality disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2000;7:413–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson KM, Tran CF. Impact of treatment intensity on suicidal behavior and depression in borderline personality disorder: A critical review. J Pers Disord. 2014;28:181–97. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2013_27_113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scheel KR. The empirical basis of dialectical behavior therapy: Summary, critique, and implications. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2000;7:68–86. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ost LG. Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:296–321. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chambless DL, Hollon SD. Defining empirically supported therapies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:7–18. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tolin DF, McKay D, Forman EM, Klonsky ED, Thombs BD. Empirically supported treatment: Recommendations for a new model. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2015;22:317–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray AM, Brown MZ, Gallop RJ, Heard HL, et al. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:757–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabbard GO. Do all roads lead to Rome? New findings on borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:853–5. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10 Suppl):1–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunderson JG. Borderline Personality Disorder: A Clinical Guide. 1st ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2001. p. 329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMain SF, Guimond T, Streiner DL, Cardish RJ, Links PS. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with general psychiatric management for borderline personality disorder: Clinical outcomes and functioning over a 2-year follow-up. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:650–61. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linehan MM, Heard HL, Armstrong HE. Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:971–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240055007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyrer P. Practice guideline for the treatment of borderline personality disorder: A bridge too far. J Pers Disord. 2002;16:113–8. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.2.113.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldham JM, Gabbard GO, Goin MK, Gunderson J, Soloff P, Spiegel D, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2010. [Last accessed on 2017 Mar 18]. Available from: http://www.psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/bpd.pdf .