Abstract

Context:

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a challenging clinical condition to manage. Recent psychological models of GAD emphasis on the need to focus on metacognitive processes in addition to symptom reduction.

Aims:

We examined the application of metacognitive strategies in addition to conventional cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) techniques in an adult patient with GAD.

Settings and Designs:

Asingle case design with pre- and post-assessments on clinician-rated scales was adopted.

Materials and Methods:

Twelve weekly sessions of therapy were conducted on an outpatient basis. Assessments were carried out on clinical global impressions scales, Hamilton's anxiety rating scale at pre- and post-therapy points.

Statistical Analysis:

Pre- and post-therapy changes were examined using the method of clinical significance.

Results:

A combination of traditional CBT with MCT was effective in addressing anxiety and worry in this patient with GAD. The case illustrates the feasibility of matching therapeutic strategies to patient's symptom list and demonstrates a blend of metacognitive strategies and conventional CBT strategies.

Conclusions:

In clinical practice, matching strategies to patient's problem list is important to be an effective approach.

Keywords: CBT, generalized anxiety disorder, metacognitive therapy

INTRODUCTION

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is characterized by autonomic hyperactivity, muscle tension, worry, and difficulties in concentration. It is also known as the basic anxiety disorder.[1,2] Cognitive behavioral models of GAD emphasize the role of worry and the use of strategies such as checking and reassurance seeking in maintaining the disorder. Worry is conceptualized as a form of cognitive avoidance that prevents emotional processing and does not allow one to examine actual probabilities of catastrophic predictions.[3,4] Intolerance for uncertainty, the need for perfectionism and control over events are cognitive processes associated with GAD. Studies indicate problem-solving skills deficits and a negative problem orientation in patients with GAD.[5,6,7]

The effectiveness of CBT for GAD is well established, including a combination of cognitive and behavioral interventions such as focusing on the content of worry using verbal challenging but it does not specifically target processes that maintain the disorder.[2]

Metacognitive therapy (MCT) for emotional disorders is based on the self-regulatory executive functions model (SREF).[8,9,10] According to the model, patients are trapped in negative emotions due to a thinking style called the cognitive attentional syndrome (CAS). Rumination and worries are examples of the CAS. MCT includes techniques such as practice of external attention monitoring, an emphasis on banning rumination, and worry and modifying beliefs about worry and detached mindfulness.[9] Preliminary evidence for MCT for GAD lends support to its effectiveness.[11,12] However, the feasibility and acceptability of this approach in the Indian setting are not known as there are no published studies on the use of metacognitive strategies in the management of GAD. A recent case series from India indicates that MCT can be effective in patients with social phobia.[13] Manualized programs developed for psychological interventions often do not offer much flexibility for the therapist in clinical practice, and there is a need for approaches that allow the therapist to select strategies to maximize therapeutic gains.

The following case illustrates the application of metacognitive strategies in addition to conventional CBT in the management of an adult patient with GAD.

CASE SUMMARY

Mr. M.K., a 34-year-old man, presented with complaints of free-floating anxiety, excessive worries over a day to day events, inability to relax, disturbed sleep, being forgetful, and difficulties in concentration. He was apparently doing well 5 years ago. Following a promotion at work, he had begun experiencing stress and difficulties in decision-making and managing time. Mr. M.K. would worry excessively about work, which would persist even when he reached home. He would ruminate excessively about the decisions he had taken, worry that he had not done well enough and would mentally check that his work was correct. He believed that going over these thoughts repeatedly would help him correct any mistakes he might have made (positive - Type-2 worry). In addition, the patient would also plan in excessive detail about all upcoming tasks and make lists of things to do and would be unable to proceed without doing this. When these worries interfered with his concentration, the patient would attempt to block these thoughts (thought suppression) or to distract himself (experiential avoidance), but would find that this was only temporarily successful, and his worries would continue. He would remain tense throughout the day, anticipating problems at work and as a result had disturbed sleep, with frequent awakening through the night, and difficulties in falling asleep.

There is history suggestive of anxious traits and worrying in patient's mother, but she has never sought help for this. His constant anxiety has strained his relationship with his spouse. The patient himself has never sought help for his problems until this consultation. He was reluctant to take medications and was referred to the Behavioural Medicine Unit for individual psychotherapy.

The patient describes himself being methodical and orderly, with a tendency to feel uneasy if things did not go according to plans (“awfulization”). Based on the cognitive behavioral interview and assessments, a therapeutic formulation was made. MCT is based on the SREF model that highlights the perseverative pattern of thinking typical of emotional disorders. Strategies used to reduce emotional distress include monitoring thoughts and threats, suppressing thoughts and checking. These strategies contribute to the maintenance of the emotional disorder.[9] We additionally focused on skill deficits such as problem-solving, decision-making, an inability to relax and negative problem orientation and included these in the therapeutic program.

Case formulation

Specific triggers identified in the assessment were sudden, unexpected changes at work, (for example, postponements, new assignments, telephone calls during meetings). These triggers were appraised as an intrusion or threats to predefined plans and fears of losing control over events, leading to activation of positive meta-beliefs (“I should worry about these to see that I do not miss out anything, I must go through the plans in details so as to do things perfectly”). Patient engaged in Type I worries, such as “I have so many things to do?” “What if there are more interruptions while I am doing this report, I might forget to put some of the details in this report. I should think about all the details clearly”

Type I worries appeared to be helpful initially but generated anxiety and led to activation of negative meta-beliefs (Worry is uncontrollable, worrying can impair my concentration on other tasks), and later negative Type II worries (“I am not able to stop myself from thinking about this call, I am not able to focus, what if this continues”). As the patient was worried about the uncontrollability of worry itself, he would attempt thought suppression, experiential avoidance using distraction strategies and repeatedly check his schedules mentally. These strategies would provide initial temporary relief but would lead to increase in symptoms as they did not allow for emotional processing and reinforced the beliefs regarding need for control and being perfect.

Therapeutic program

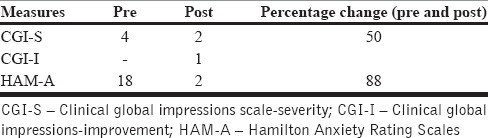

Therapy was conducted over 12 weekly sessions, on an outpatient basis by the second author (SR). In the first two sessions, symptom severity was assessed along with an analysis of his coping strategies and frequency, intensity of distress and triggers for worries. Assessments were carried out using clinician-rated scales. On the clinical global impressions scale-severity (CGI)[14] patient scored, 4 indicating moderate illness and on Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) he obtained a score of 18, indicating mild-moderate level of anxiety.[15]

An analysis of metacognitive strategies and beliefs was initiated using interviews and a self-monitoring record in which he was asked to record triggers, frequency, and duration of worries, subjective distress, coping strategies, and safety behaviors.

Following this, a working model of the metacognitive formulation was presented to the patient, including the vicious cycle of triggers, appraisals, emotions, and behaviors. The role of positive and negative beliefs about worry was introduced along with beliefs regarding perfectionism, intolerance of uncertainty and how they maintained the problems.

In sessions 3-4, the patient was introduced to the practice of progressive muscle relaxation so as to address somatic symptoms which induced sleep difficulties and he was encouraged to practice it regularly at home, with a plan to reduce the time taken to relax.[16] Although MCT does not include relaxation training, we considered it relevant to address patient's somatic complaints and to increase awareness of thoughts and sensations to facilitate later practice of mindful self-awareness.

Following this, a drop in safety behaviors such as checking, planning, and list making was planned. Using a Socratic dialogue, the therapist elicited negative and positive beliefs regarding worry. Behavioral experiments based on the prepared expose test and summarize model were introduced to test predictions across beliefs and to help challenge the utility of safety behaviors.[17] For example, he was encouraged to drop excessive planning for a day and see how he would manage things, comparing it with a typical day in which he had planned everything. To modify positive meta-beliefs (“Worry will help me cope”), the patient was asked to generate evidence for and against these using examples. He was asked to recall situations when he had had no time to worry or plan and how he had coped. Thus, behavioral experiments were designed to test his predictions regarding negative consequences of not worrying. A ban on rumination and worry was introduced since beliefs maintaining these had been weakened. Attention control training was introduced to address rumination, which would help him remain focused on the tasks in the present. As the patient was already practicing relaxation, the concept of detached mindfulness was introduced.[9] Using metaphors such as watching passing clouds and being a bystander at a traffic junction, the patient was helped to develop the practice of observing his thoughts without reacting to them (appraisals regarding worries).

Patient's difficulty in making decisions and stress at work was discussed in further sessions in relation to beliefs about perfectionism and need for order. The patient was asked to consider factors in his control, those that were not in his control, he was then helped to identify these factors in stressful situations. He was asked to recognize if he was trying to exercise control over factors beyond his control. Socratic questioning was used primarily to challenge irrational beliefs. The patient was encouraged to set realistic and flexible goals (“I have to expect that I will be interrupted” “I can’t expect the workplace to be like a calm pond”) as against idealistic goals at work (“I must never be interrupted” “The day at work should be smooth and calm”). Probability estimates of negative consequences if he did not plan out things in minute detail were discussed with him.

Time management was discussed as patient's worries about his schedule would interfere with efficient work process. Strategies included keeping a time log, prioritizing, planning ahead but not rigidly, and task delegation. Release only relaxation was introduced to facilitate relaxation response in a shorter time. Reappraisal and acceptance as more adaptive emotion regulation strategies were discussed and the patient was helped to recognize the paradoxical nature of strategies such as mental checking and suppression of worries.

In the last two sessions, a plan for relapse prevention was drawn in collaboration with the patient. The skills acquired were reviewed, and he was encouraged to drop residual usage of safety behaviors. The nature of beliefs likely to be activated in stressful situations was reviewed along with a plan for application of detached mindfulness and attention control techniques. Patient's efforts and participation in therapy were reinforced.

RESULTS

Using the formulation for clinical significance, the percentage of improvement was calculated.[18] Posttherapy assessment on CGI-Improvement, severity, and HAM-A indicated a significant improvement in symptom severity. Percentage improvements on CGI-S and HAM-A were 50% and 88%, respectively [Table 1].

Table 1.

The pre- and post-therapy assessment on clinician rated scales

Patient-rated his improvement as 80% on a visual analog scale. He reported feeling more confident in managing his worry and taking decisions, feeling less tense, and getting better sleep. There were some occasional difficulties in concentration. The patient reported that the use of mindful awareness at such times was effective.

DISCUSSION

The case illustration demonstrates the feasibility of blending metacognitive strategies with conventional CBT in the management of GAD. Conventional CBT employs verbal challenge and symptom reduction through relaxation and coping skills training. More recent approaches to the management of GAD emphasize the need to target maintaining processes such as beliefs about worry and metacognitive strategies.[19] MCT focuses on these processes specifically, but with little or no verbal challenge or skills training. Research indicates a significant overlap between cognitive phenomena such as worry, rumination as well as their association with negative affective states and emotion regulation difficulties,[19,20] thereby suggesting a need to adopt an approach that is guided by patient needs.

We combined conventional CBT, with specific metacognitive strategies, so as to systematically address patient's symptoms, skill deficits and beliefs such as problem-solving skills deficits and negative problem orientation.

There are no studies examining the relative contribution of various therapeutic strategies across CBT and MCT. Both approaches are likely to bring about changes in symptoms, although individual MCT techniques may target cognition more specifically.[21] The case presented illustrates the feasibility of combining essential strategies in clinical practice.

Improvements seen on clinician-rated measures lend support to the finding that flexibility of treatment approaches is feasible and important, particularly in clinical settings, where manualized approaches may pose practical problems. The absence of assessment on specific measures of worry and metacognition and a follow-up is a limitation of this case illustration. These would have helped assess the effect of a combined approach on worries and metacognitions and the durability of gains.

CONCLUSIONS

Combining traditional CBT with metacognitive strategies in managing generalized anxiety disorder is effective and must be considered in clinical practice when matching strategies with client's problems.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown T, O’Leary T, Barlow D. Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Barlow DH, editor. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders: A Step-by Step Treatment Manual. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Publications; 2001. pp. 154–208. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borkovec TD. The nature, functions, and origins of worry. In: Davey G, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: Perspectives on Theory Assessment & Treatment. Sussex, England: Wiley and Sons; 1994. pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borkovec TD, Alcaine OM, Behar E. Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In: Heimberg R, Turk C, Mennin D, editors. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dugas MJ, Buhr K, Ladouceur R. The role of intolerance of uncertainty in etiology and maintenance. In: Heimberg RG, Turk CL, Mennin DS, editors. Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances in Research and Practice. New York: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dugas MJ, Freeston MH, Ladouceur R. Intolerance of uncertainty and problem orientation in worry. Cognit Ther Res. 1997;21:593–606. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dugas MJ, Letarte H, Rheaume J, Freeston MH, Ladouceur R. Worry and problem solving: Evidence of a specific relationship. Cognit Ther Res. 1995;19:109–20. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells A, Matthews G. Attention and Emotion: A Clinical Perspective. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells A. Metacognitive Therapy for Anxiety and Depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells A. Cognition about cognition: Metacognitive therapy and change in generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. Cogn Behav Pract. 2007;14:18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells A, Welford M, King P, Papageorgiou C, Wisely J, Mendel E. A pilot randomized trial of metacognitive therapy vs applied relaxation in the treatment of adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:429–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennair LE, Nordahl HM. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Effectiveness of Cognitive Behavior Therapy with Metacognitive Therapy in the Treatment of Patients with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. 2011. [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00426426 .

- 13.Lakshmi J, Sudhir PM, Sharma MP, Bada Math S. Effectiveness of metacognitive therapy in patients with social anxiety disorder: A preliminary investigation. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016 doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.191385. [Epub ahead of Print (AOP)] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Publication (ADM) 76–338. Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976. pp. 218–22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–5. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ost LG. Applied relaxation: Description of a coping technique and review of controlled studies. Behav Res Ther. 1987;25:397–409. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wells A. Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: A Practice Manual and Conceptual Guide. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchard EB, Schwarz SP. Clinically significant changes in behavioral medicine. Behav Assess. 1988;10:171–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roemer L, Lee JK, Salters-Pedneault K, Erisman SM, Orsillo SM, Mennin DS. Mindfulness and emotion regulation difficulties in generalized anxiety disorder: Preliminary evidence for independent and overlapping contributions. Behav Ther. 2009;40:142–54. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fresco DM, Frankel A, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognit Ther Res. 2002;26:179–88. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells A. Metacognitive therapy: Cognition applied to regulating cognition. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008;36:651–8. [Google Scholar]