Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) hierarchical nanoscale architectures comprised of building blocks, with specifically engineered morphologies, are expected to play important roles in the fabrication of ‘next generation’ microelectronic and optoelectronic devices due to their high surface-to-volume ratio as well as opto-electronic properties. Herein, a series of well-defined 3D hierarchical rutile TiO2 architectures (HRT) were successfully prepared using a facile hydrothermal method without any surfactant or template, simply by changing the concentration of hydrochloric acid used in the synthesis. The production of these materials provides, to the best of our knowledge, the first identified example of a ledgewise growth mechanism in a rutile TiO2 structure. Also for the first time, a Dye-sensitized Solar Cell (DSC) combining a HRT is reported in conjunction with a high-extinction-coefficient metal-free organic sensitizer (D149), achieving a conversion efficiency of 5.5%, which is superior to ones employing P25 (4.5%), comparable to state-of-the-art commercial transparent titania anatase paste (5.8%). Further to this, an overall conversion efficiency 8.6% was achieved when HRT was used as the light scattering layer, a considerable improvement over the commercial transparent/reflector titania anatase paste (7.6%), a significantly smaller gap in performance than has been seen previously.

The design and growth of inorganic nanostructures with well-controlled sizes and morphologies have been the focus of intensive research in recent years due to their wide ranging applications. TiO2 is a functional material used in many ways, such as in photocatalysis, photoelectrochemical solar energy conversion1, and Li-ion batteries2. The properties and applications of TiO2 are generally correlated to crystal phase, dimensions, morphology, and surface properties. As such, rationally designed and controlled nanostructured TiO2 has attracted great interest3,4. Various TiO2 nanostructures in the forms of spheres, tubes, wires, rods, sheets, belts, flowers, and trees have been reported5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Three-dimensional (3D) hierarchical structures are of particular interest as many of these architectures have distinctive physicochemical properties in comparison with simple nanocrystallites13,14. When employed as the photoanode in a Dye-sensitized Solar Cell (DSC), hierarchical architectures can offer larger surface areas for dye adsorption while simultaneously enhancing light scattering for efficient photon harvesting, and thereby, improving power conversion efficiency15,16,17,18. Chemical vapor deposition, applications of templates, catalysts and electrochemical methods are known to be used for the direct growth of inorganic material with controlled morphologies and architectures19,20,21,22,23,24, however, in most cases, the mechanisms involved in the formation of these hierarchical structures are complicated and not well-understood.

Crystalline TiO2 mainly exists in three polymorphs: anatase (tetragonal), rutile (tetragonal) and brookite (orthorhombic). The majority of research has been carried out on anatase, while rutile is often ignored in DSCs, possibly due to the expectation that rutile would result in a lower open-circuit voltage (Voc) than anatase because rutile has a more positive conduction band edge potential4,25. Slow electron transport is also often seen as a detracting feature of rutile TiO2, this, however, may lead to higher electron densities within the conduction band, subsequently increasing the quasi Fermi-level, and mitigating the aftermentioned concern about conduction band edge potential. Indeed, studies show that rutile TiO2 can achieve a similar26 or even higher Voc through doping27. Furthermore, compared to anatase, the rutile polymorph exhibits some superior physical properties, such as enhanced light-scattering properties on account of its higher refractive index, which is beneficial from the perspective of effective light harvesting28. Rutile TiO2 is also chemically more stable and potentially cheaper to produce than anatase26. These findings suggest that additional research on rutile TiO2 from the perspective of solar energy conversion would be fundamentally interesting.

The majority of DSCs use Ru-based complexes (e.g., N329, N71930,31, and black dye32), as sensitizers of TiO2, offering a high solar-to-electric conversion efficiency and good stability. The cost of the Ru-based sensitizers, however, is high and their synthesis and purification are complicated. Indoline-based dyes, such as D149 are promising all-organic alternatives33. Gratzel and co-workers have produced devices based on D149, which have displayed power conversion efficiency of up to 9%34. Furthermore, D149 has a peak extinction co-efficient of 68700 M−1 cm−1 at 540 nm, significantly higher than 13900 M−1 cm−1 at 535 nm for N71935. In addition, it has been reported that rutile TiO2 has a tendency for low dye loading26,28, even on relatively high surface area materials, compared to anatase. The use of high extinction dye should help to overcome this constraint, allowing for comparable light harvesting.

In the present paper, we report a new series of 3D hierarchical rutile TiO2 architectures (HRT) with controlled morphologies and sized subunits by the aid of a facile acid-hydrothermal method, without any surfactant or template. We demonstrate that the hydrochloric acid (HCl) concentration plays an important role in controlling the hydrolysis rate of tetrabutyl titanate (TT) in the acid-hydrothermal process, which in turn enables us to fine-tune the final properties of rutile TiO2. Different, well-defined 3D HRT were produced using 1–8 M HCl (denoted as HRT-1 – HRT-8, respectively). Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first observation of ledgewise growth for rutile TiO2.

Furthermore, we report a solar-to-electric conversion efficiency of 5.5%, achieved using a HRT as the photoelectrode with D149 dye, which is significantly better than devices made using P25 (4.5%) and comparable to state-of-the-art commercial transparent titania anatase paste (5.8%). This power conversion efficiency is due to a considerable surface area for the high dye adsorption and a superior light scattering ability. In addition, an overall conversion efficiency 8.6% was achieved when HRT was used as the light scattering layer on top of a transparent anatase layer, a considerable improvement over commercial transparent/reflector titania anatase paste (7.6%).

Results

All the prepared samples are of the rutile phase (a = b = 0.45927 nm, c = 0.29544 nm, space group P42/mnm), as shown by the XRD pattern in Supplementary Fig. S1(a), with all the peaks corresponding well with JCPDS No. 21-1276. No characteristic peaks of impurities such as anatase TiO2, brookite TiO2 or Ti(OH)4 were detected and all the observed diffraction peaks suggest that the products are well crystallized. These peaks are essentially invariant with HCl concentration, as all of the morphologies appear to be of the rutile TiO2 phase, with the Raman spectrum in Supplementary Fig. S1(b) further confirming the formation of rutile crystals. The two Raman active fundamental modes, Eg (~438 cm−1) and A1g (~607 cm−1), as well as a second-order phonon as identified by Porto et al.36, (~247 cm−1), and the combination of shoulders at 350, 548, and 688 cm−1, which are assigned to rutile TiO2, can be clearly distinguished.

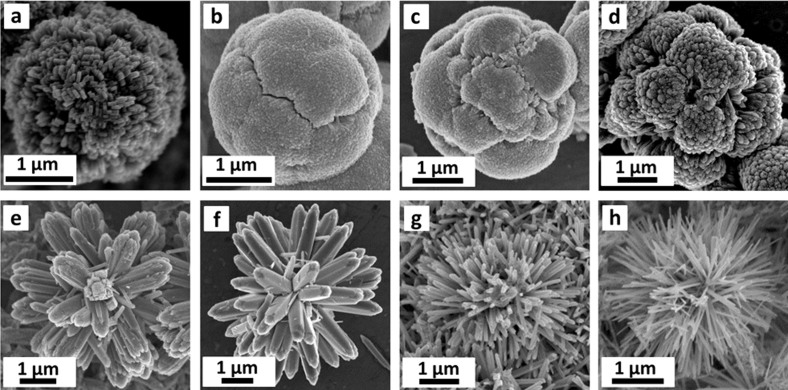

Figure 1 (a–h) shows typical field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of HRT samples, synthesized in a tightly sealed 45 mL Teflon-lined autoclave, from a reaction solution containing 0.5 mL precursor aqueous tetrabutyl titanate (TT) solution with 25 mL of 1 M–8 M hydrochloric acid (HCl), at 150°C for 5 h.

Figure 1. FESEM images of the as-prepared 3D hierarchical rutile TiO2 architectures (HRT) [denoted as HRT-1 (a), HRT-2 (b), HRT-3 (c), HRT-4 (d), HRT-5 (e), HRT-6 (f), HRT-7 (g), HRT-8 (h)], synthesized from a reaction solution containing 0.5 mL aqueous tetrabutyl titanate (TT) solution with 25 mL X M hydrochloric acid (HCl) (X = 1–8).

For the lowest HCl concentration, 1 M, HRT-1, uniform, textured microspheres with diameters of ~1–1.5 μm are observed in low magnification SEM [Supplementary Fig. S2(a)]. It can be seen from higher magnification SEM [Fig. 1(a)] that the structure is composed of large quantities of elongated crystalline nanorods, which are closely packed and possess square profiles. FESEM of a fractured microsphere of the same material, in Supplementary Fig. S2(b), reveals that these densely packed crystalline nanorods (each with diameters of 15–30 nm) are radially arranged. It was found that the microspheres were formed by radial growth of nano-acicular crystals on the TiO2 nanoparticulate core. Noticeably, smaller but also radially aligned nanorods form the core. It is from this surface that, nanorods with a mean width of ~20 nm and a length of ~500 nm, grew forming the TiO2 microsphere.

The structures of HRT-2 and HRT-3 in the hydrothermal process, some-what resembling tennis balls, are 2–2.5 μm in diameter, as shown in Fig. 1(b and c). The domain like arrangements of the TiO2 nanorods form quasi spheres leading to an apparently smooth surface. The surfaces of these spheres are in fact densely packed nanorods. Samples prepared with 4 M HCl resulted in the formation of morphology likened to a cauliflower, comprised of the near-perfect assemble of numerous TiO2 nanorods, as the nanorod bundles are smaller and more disparate [Fig. 1(d)].

SEM of samples HRT-5 and HRT-6 [Fig. 1(e and f)] revealed even more open morphologies with the nanorod bundles more separated from each other. Each of these bundles is assembled from several dozen nanorods of lengths of up to 3 μm. The distribution of quasi-cubic primary nanocrystallites with sizes 15–25 nm led to the observation of surfaces which may be likened to flowers. These differences are due to the initial differences in crystal growth of the titanium precursor in the stronger acidic medium (described in more detail below). The observation of nanostructures indicate that the formation of prisms and the flower-like structures, possibly stemmed from the crystal growth of the primary nanoparticles and the further epitaxial process of these prisms.

High HCl concentrations of HRT-7 and HRT-8 resulted in even more open structures again, as the surface etching rate is much faster and thus tends to result in more nucleation sites at early stages of synthesis. The resulting nanorods bundles are thinner as they contain fewer rods [Fig. 1(g, h)]. At these concentrations, structures composed of hundreds of nanoneedles were produced. It is known that high HCl concentration is favorable for the formation of smaller-scale building blocks37.

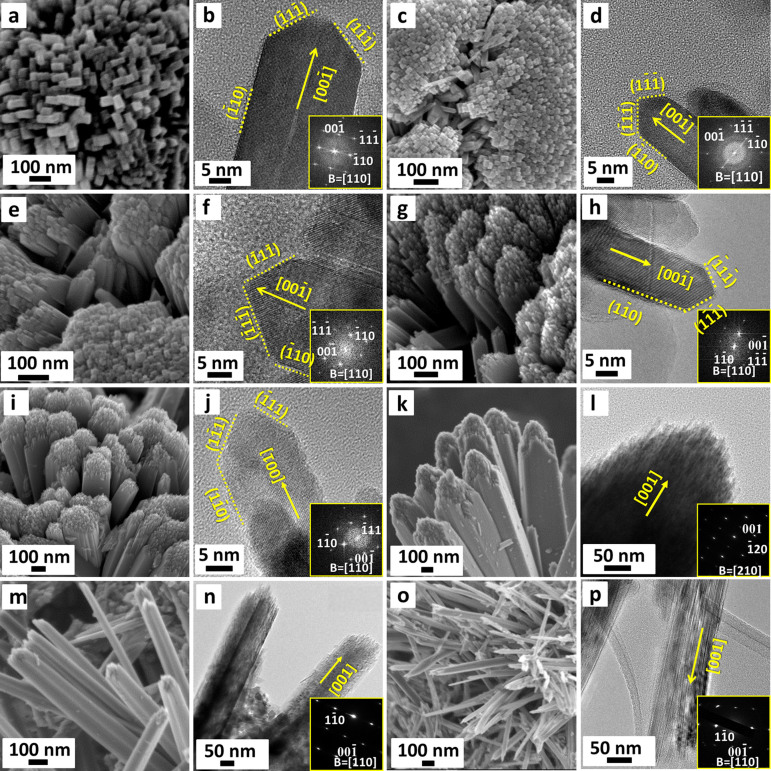

To elucidate the microstructural origin of the growth mechanisms, the architectures of the HRT obtained under different HCl concentrations were further investigated by high resolution SEM, high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) of the HRTEM images. Figure 2(a) presents a high-magnification SEM image obtained from the synthesis completed using 0.5 mL of TT and 1 M HCl. Figure 2(b) shows the TEM image of a single nanorod (prepared under the same conditions) with a width of ~20 nm. The FFT pattern is shown in inset of Fig. 2(b) and, along with the associate HRTEM image, confirm the single-crystal nature of the rutile TiO2 rods.

Figure 2. (a, c, e, g, i, k, m, o) High-magnification SEM images of HRT-1 to HRT-8, respectively; (b, d, f, h, j) TEM images of individual nanorods; (l, n, p) TEM images of nanorod bundles.

The insets of (b, d, f, h, j, l, n, p) are the corresponding FFTs (b, d, f, h, j) and electron diffraction patterns (l, n, p).

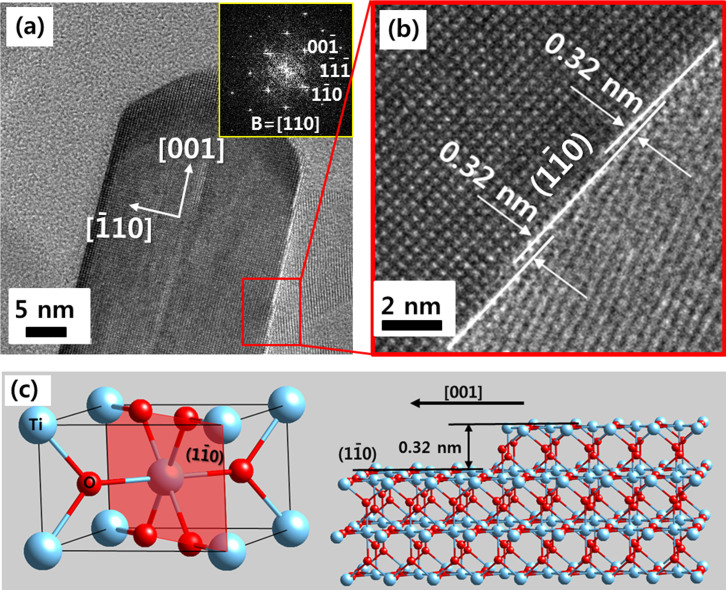

It can be observed from Fig. 2 that the rutile crystals (HRT-1 to HRT-5) can be described by a combination of an elongated cuboid structure and pyramid shaped cap [this is also seen in Fig. 3(a) and schematically in Supplementary Fig. S3(a)]. Two sets of lattice fringes perpendicular to each other with distances of 0.29 and 0.32 nm can be readily ascribed to the lattice spacings of the (001) and (110) planes of the rutile TiO2 respectively [Supplementary Fig. S3(b)]. The FFT pattern [inset of Fig. 2(b)] further confirms that (1) the cuboid crystal facets are parallel to {110}, (2) the pyramid-shaped crystal facets are parallel to {111}, and (3) a preferred growth along the [001] direction takes place. Moreover, according to periodic bond chain (PBC) theory, PBCs result in the formation of the crystal and control the direction of crystal growth (the strongest chemical bonds are usually the ones at which the crystal has the fastest growth rate)38,39. Theoretical calculation shows that for a rutile lattice, the surface energy is E (110) < E (100) < E (101) < E (001)40. In crystal growth, a fast growing plane generally tends to disappear leaving behind slower growing planes with lower surface energies. Thus, crystal growth along the [001] direction (i.e., c -axis) would have the fastest growth rate compared to other directions.

Figure 3. Ledgewise growth of rutile nanorod (HRT-1).

(a) Macro growth direction of a rutile nanorode; preferential growth to [001] direction, (b) Thickening of a nanorode by ledgewise growth of  surface, (c) atomic structure of a rutile nanorod.

surface, (c) atomic structure of a rutile nanorod.

Interestingly, the top of all the rods are pyramidally capped, as shown in Fig. 2. HRTEM imagery of the rod [Fig. 2(b)] indicates that the plane of the pyramid has a contact angle of approximately 130° to the lateral {110} plane. The most appropriate plane is considered to be {111} under this condition because contact angles between {110} and {101}, {110} and {111}, and {110} and {221} planes are calculated to be 112.5°, 132.3°, and 151.2°, respectively, using the tetragonal rutile unit cell41.

No crystallographic differences were observed between HRT-1 and HRT-8. Our results then demonstrate that {111} and {110} faceted rods are obtained during the hydrothermal growth. It should be noted that the {111} planes observed at the top surface of the rods are a minor surface in the equilibrium shape of a macroscopic rutile TiO2 crystal using the Wulff construction and the calculated surface energies. According to the atomistic simulation reported by Oliver et al.42, rutile TiO2 shows four surfaces namely {011}, {110}, {100}, and {221}, with surface energies of 1.85, 1.78, 2.08, and 2.02 J m−2 respectively in the relaxed equilibrium morphology. Nevertheless, the surface identified as the {221} plane had formerly been thought to be the lower index plane of {111}. Because the {111} plane, or alternatively {221}, governs a very small surface area in the equilibrium shape, experimental observation of this plane has been considerably difficult41. In contrast to the simulation by Oliver et al.42, our results have shown the presence of the {111} facet with a large surface area, giving rise to the pyramid-type morphology. The authors believe these results give important new insight into the surface chemistry of rutile TiO2. It is reasonable to expect that the TiO2 nanorods preferentially exposes the {110} side facets and the {111} top facets and grows along the [001] direction on the basis of the FESEM and HRTEM results together with the XRD pattern.

Figure 2 (c–j) shows the morphology and structure of the nanorods bundles and individual rods for HRT-2 to HRT-5. To further obtain structural information for the radial rods, TEM images and the corresponding FFT patterns are also recorded on a single nanorod of each (for HRT-6 to HRT-8, however, only bundles of nanorods were taken because the samples were brittle and no loose bundles could be identified, probably because of bundles more open but rods within each bundle more tightly held together). Based on Fig. 2 it can be seen that, similar to HRT-1, the TiO2 nanorod synthesized with 2 M–5 M HCl, also preferentially exposes the {110} side facets and the {111} top facets and grows along the [001] direction. In addition, the nanorod crystals of the HRT synthesized in the highest HCl concentration solutions (6 M–8 M) grew along the [001] direction. The exposed surfaces of the nanorods are {110} facets. The variation of HCl concentration in the reaction solutions did not affect the crystal growth direction of the nanorods.

In spite of the differences in micron-scale morphologies, all the architectures are composed of very similar crystalline nanorod units. It has been demonstrated previously that Cl− plays an important role in the growth of TiO2 grains into nanorods (as opposed to nanoparticles). This is because the {110} planes of rutile have a positive polar face and Cl− is preferentially adsorbed on this surface, which serves to restrain the contact of TiO2 grains on the {110} surfaces and thus greatly retards crystal growth along the (001) plane43,44. As a result, TiO2 grain growth was suppressed in the <110> directions and accelerated in the [001] direction, thereby forming rod-like structures. Additionally, the presence of 42 screw axes along the crystallographic c-axis within rutile TiO2 is also believed to be a guiding force for the formation of rutile nanorods45.

It is interesting that a ledgewise growth mechanism was observed for HRT-1, as shown in Fig. 3. Preferential growth of a rutile nanorod to the [001] direction is also confirmed by overview of a nanorod [Fig. 3(a)]. The growth rate in the [001] direction is much faster than that of the  direction, resulting in an elongated morphology in the [001] direction. Lateral growth of a nanorod, ie. the diameter increasing, occurs with the generation of a fresh

direction, resulting in an elongated morphology in the [001] direction. Lateral growth of a nanorod, ie. the diameter increasing, occurs with the generation of a fresh  surface. High resolution images of the side of a nanorod show several steps on a

surface. High resolution images of the side of a nanorod show several steps on a  plane [Fig. 3(b), Supplementary Fig. S3(b)]. Importantly, these steps have a step height of 0.32 nm, coincident with interplanar spacing of a

plane [Fig. 3(b), Supplementary Fig. S3(b)]. Importantly, these steps have a step height of 0.32 nm, coincident with interplanar spacing of a  plane. This ledgewise growth mechanism minimizes the total surface energy during growth of nanorod [Fig. 3(c)], as a monolayer step will minimize the amount of high surface energy area. The total

plane. This ledgewise growth mechanism minimizes the total surface energy during growth of nanorod [Fig. 3(c)], as a monolayer step will minimize the amount of high surface energy area. The total  surface area which has minimum surface energy is kept constant during growth. The growth of a rutile nanorod is displayed schematically in Supplementary Fig. S3(a). The cuboidal body has {110} type surface and the upper pyramidal cap is composed of {111} planes.

surface area which has minimum surface energy is kept constant during growth. The growth of a rutile nanorod is displayed schematically in Supplementary Fig. S3(a). The cuboidal body has {110} type surface and the upper pyramidal cap is composed of {111} planes.

Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) calculations of specific surface area based on N2 adsorption-desorption were performed (Supplementary Table S1), however, HRT-5 –HRT-8 were omitted from this due to the low yields which lead to large measurement errors. The specific surface area is found to decrease with increasing concentration of HCl used in synthesis. N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms (shown in Supplementary Fig. S4) of the samples (HRT-1 – HRT-4) exhibited typical type IV sorption behavior with hysteresis loops, ascribed to the existence of the mesoporous structure.

On account of it having the highest specific surface area (and highest yield among all the samples), HRT-1 was applied in photoanodes for DSCs. Two control materials were employed for comparative purposed. Firstly, P25 was used, as it is low cost and widely reported in this field. P25 also represents a mixed phase material (mostly anatase, with a significant rutile impurity). A commercial transparent titania anatase paste [18NR-T, denoted as Dyesol-T, obtained from Dyesol (Australia)] was also chosen for its role in some of the highest reported DSC efficiencies to date.

The porosity (P) and surface roughness factor (R) based on adsorption-desorption measurements were measured for the two controls and compared with HRT-1, summarized in Table 1. HRT-1 is >50% porous, which is promising as porosities of nanocrystalline TiO2 films employed in high efficiency DSCs are typically in the range of 50–65%. HRT-1 has a similar specific surface area as Dyesol-T (74 m2 g−1), but significantly higher than P25. Furthermore, the calculated roughness factor for HRT-1, approximately 125 μm−1, which is higher than both P25 and Dyesol-T.

Table 1. Specific surface area, porosity, and roughness factor of P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T materials.

| Samples | Specific surface area (m2 g−1) | Porosity a) (%) | Roughness factor b) (μm−1) | Amount of dye c) (10−7 mol cm−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P25 | 42 | 34.9 | 118 | 2.4 |

| HRT-1 | 67 | 56.6 | 125 | 2.7 |

| Dyesol-T | 74 | 64.2 | 103 | 3.4 |

a)The porosities (P) of P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T were calculated according to: P = Vp/(ρ−1 + Vp), where Vp is the specific cumulative pore volume (cm3 g−1) and ρ is the density of TiO2 (ρ = 4.3 g·cm−3)50.

b)An estimation of the roughness factor (R) per unit film thickness of the films is obtained by R = ρ (1 − P) S, where ρ is the density (g cm−3) of TiO2, P is the porosity (%) of the film, and S is the specific surface area (m2 g−1)51.

c)The dyed electrodes were soaked in a 0.4 M alkaline solution in methanol to desorb the dye from the electrodes. The amount of desorbed dye was quantified by measuring its optical absorption spectrum (Supplementary Fig. S6).

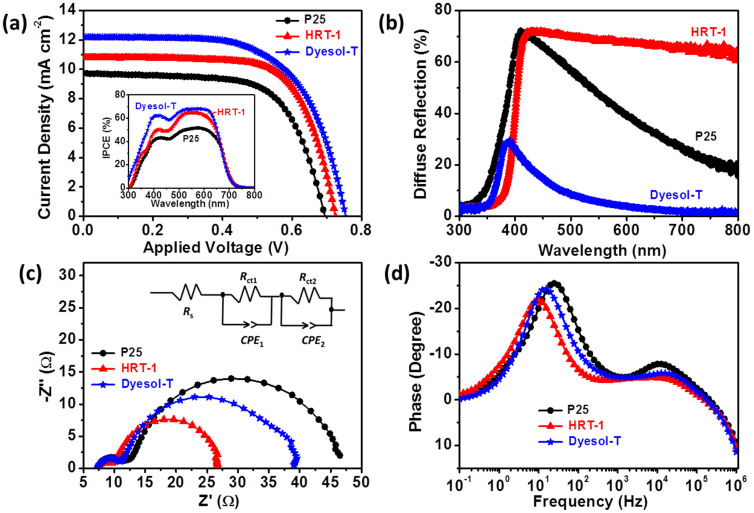

The photocurrent density-voltage (J-V) curves of P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T based DSCs (each with ~12 μm porous TiO2 layer), are shown in Fig. 4, (summarized in Supplementary Table S2). From this, it can be found that the overall energy conversion efficiency (η) of HRT-1 was higher than P25 but lower than Dyesol-T. The short-circuit photocurrent density (Jsc) is highest in the devices with Dyesol-T, then HRT-1, and lowest when P25 is used. This order is repeated in the dye loading data collected (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S6), however is probably not the whole story with regard to light harvesting efficiency (LHE). The higher Jsc for HRT-1 based devices than P25 could be mainly attributed to the improved dye loading capacity, attributable to measured R and BET surface area results, as well as light scattering properties of the TiO2 films. In both cases the materials are scattering. It can be expected that this will actually cause some problems, with reflection near to the front surface causing light to be lost46.

Figure 4.

(a) J-V characteristics of P25-, HRT-1- and Dyesol-T-based DSCs. Cells were illuminated at an intensity of 100 mW cm−2 with a spectrum approximately AM 1.5 G and an active area of 0.16 cm2; inset: incident photon to current conversion efficiency (IPCE) curves of P25-, HRT-1- and Dyesol-T-based DSCs. (b) diffuse reflectance spectra of P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T films. Impedance spectra of DSCs containing P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T photoanodes measured at Voc under illumination of 100 mW cm−2: (c) Nyquist plots, with the inset showing the equivalent circuit, and (d) Bode phase plots.

Light scattering generally serves to improve LHE. As shown in Fig. 4(b), HRT-1 is a much more effective light scattering material than either P25 or Dyesol-T (the reflectance spectrum from 400 to 800 nm). In order to better scrutinize the different photovoltaic performances of these three solar cells, the incident photon-to-current efficiency (IPCE) spectra as a function of wavelength was collected. The IPCE [inset of Fig. 4(a)] is defined as the ratio of the number of electrons extracted the external circuit (under short circuit conditions) divided by the number of incident photons as a function of the wavelength of incident light. As such, it is a function of LHE as well as charge injection, φinj, and charge transport efficiencies, φcc.

It is observed that devices made with HRT-1 possess a marginally lower peak IPCE values than that of Dyesol-T devices and significantly higher than P25. This is an important point to obeseve as it suggests that φinj for HRT-1 should be similar to Dyesol-T [and close to unity, given the light transmission of the fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrate]. The lower IPCE values recorded away from the dye peak absorbance wavelength can be attributed to either lower φcc (addressed below) or light being reflected out of the cell before it can be absorbed by a dye molecule. At the maximum value of the IPCE spectrum at around 530 nm, the IPCE of the HRT-1 film is approximately 10% higher than that of the P25 film. This increase is in good agreement with the increased Jsc and η observed in Fig. 4(a) and Supplementary Table S2.

Measured Voc under one sun illumination follows the same trend as Jsc (Dyesol-T > HRT-1 > P25). Having said this, the difference between the pure anatase and pure rutile devices here is much less (~30 mV) than would be expected based solely on conduction band offsets (~200 mV). Perhaps the most surprising aspect of these results however is the enhanced fill factor (FF) for HRT-1 compared to the other two materials. This is analyzed in greater detail below.

The highly faceted nature of these structures results in less defect sites compared to flame pyrolysed P25, which should serve to decrease electron recombination for TiO2 to I3− in the electrolyte. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) is a very useful tool for understanding the kinetics of electrochemical and photoelectrochemical processes occurring in DSCs47,48. Fig. 4(c) presents the Nyquist plots of the impedance spectra obtained under illumination for DSCs assembled with P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T films under Voc, and the equivalent circuit is shown as the inset. The figure shows Nyquist plots with two semicircles. All Rs values are similar (7.0–7.5 Ω). The left semicircle (high frequency) represents the resistance at the counter electrode (Rct1) for the reduction reaction of I3− ions in the electrolyte using Pt as the counter electrode. The second semicircle in the intermediate frequency range results from charge transport through the semiconductor, while the corresponding chemical capacitance (Cμ) describes the density of states in the bandgap of TiO2. These parameters were calculated from measured data by using an equivalent circuit [inset of Fig. 4(c)] as shown in Supplementary Fig. S7 and Supplementary Table S3.

According to Adachi et al.49, several parameters related to the properties of electron transport in the semiconductor can be deduced from the Nyquist plot. In particular, the charge transport resistance (Rct2) related to electron-hole recombination can be determined from the central arc diameter. In our case, it was found that Rct2 at the TiO2/dye/electrolyte interface for HRT-1 was much smaller than for P25 and Dyesol-T, implying a relatively faster electron transfer process and a slower electron recombination at the HRT-1 photoanode interface. Meanwhile, the higher Cμ value of the HRT-1-based DSC indicates that more states on the TiO2 surface are able to accept electrons from the excited state of the dye, yielding an increased photocurrent. Furthermore, the Bode phase plots shown in Fig. 4(d) likewise support the differences in the electron lifetime for the TiO2 films derived from P25, HRT-1 and Dyesol-T. The electron lifetime (τeff) could be calculated from the low frequency results as:

|

where the characteristic fmax is the maximum phase shift in the mid-frequency peak. The middle-frequency peaks of the DSCs containing P25 and Dyesol-T shift to higher frequency relative to HRT-1, indicating a longer electron lifetime for the latter material. The longer electron lifetime observed with HRT-1-sensitized solar cells indicates more effective suppression of the back-reaction of the injected electrons with the I3− ions in the electrolyte. With these considerations, it seems likely that the limitations of the rutile materials are not connected to φcc, implying that reflecting light out of the cell before it can be absorbed is the major limiting factor here. It is quite interesting to note that charge transport through HRT-1 is better than for the other materials, in spite of the bulk charge transport values being lower in rutile than anatase. The longer electron lifetime is likely due to morphology of rods in the larger constructs.

Previous studies showed that, lower dye loadings (N719) on rutile compared to anatase, for the same thickness, is the main reason for lower Jsc and η26. However, using organic sensitizer (D149) in our study allows us to realize similar light harvesting for both rutile and anatase.

As an additional experiment, the light scattering properties of HRT-1 were compared to a commercially available reflector titania anatase paste [WER2-O, denoted as Dyesol-S, obtained from Dyesol (Australia)]. Once again, this has been used by a number of groups around the world in order to produce high efficiency devices.

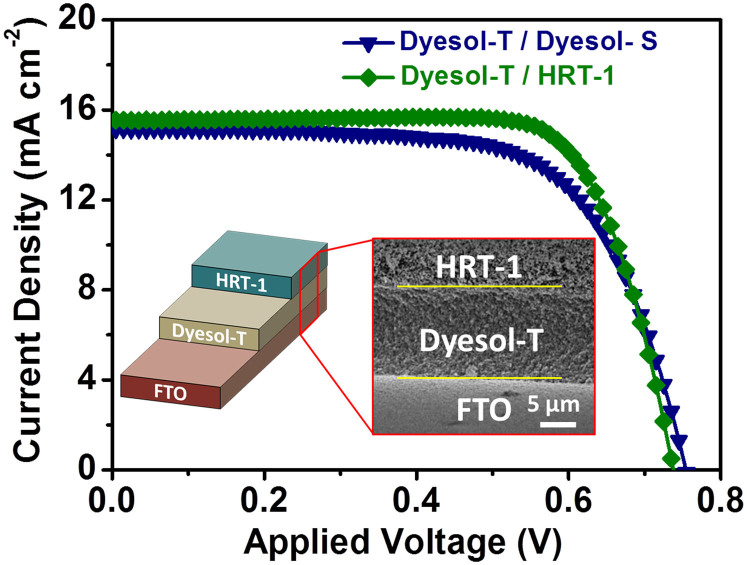

Both scattering layers were applied on top of a ~12 μm thick layer of Dyesol-T, with diffuse reflectance spectra of Dyesol-T (~12 μm)/Dyesol-S (~4 μm) and Dyesol-T (~12 μm)/HRT-1 (~4 μm) films shown in Supplementary Fig. S8. Both these materials provided enhanced performance efficiencies, with the most marked improvement being seen when HRT-1 is employed. Figure 5 (summarized in Supplementary Table S4) shows the J-V curves of DSCs using the two scattering layers. A Jsc of 15.5 mA cm−2, Voc of 740 mV, FF of 75.0%, and an overall η of 8.6% was obtained for Dyesol-T/HRT-1 films, under AM 1.5 G one sun intensity, which is superior than the optimized Dyesol-T/Dyesol-S (7.6%). Much of this improvement can be attributed to high FF when HRT-1 is used, compared to Dyesol-S. Investigations into the root cause of this are ongoing.

Figure 5. J-V curves of optimized DSCs based on a Dyesol-S film as the light scattering layer over a Dyesol-T under layer [Dyesol-T (12 μm)/Dyesol-S (4 μm)] and a HRT-1 film as the light scattering layer over a Dyesol-T under layer [Dyesol-T (12 μm)/HRT-1 (4 μm)] under AM 1.5 G one sun intensity.

Inset is a titled SEM cross-sectional image of Dyesol-T (12 μm)/HRT-1 (4 μm) on the fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) and its schematic illustration.

Discussion

In summary, different well-defined 3D hierarchical rutile TiO2 architectures (HRT) have been synthesized via a facile hydrothermal method without any surfactant or template. A ledgewise growth was observed for the first time on rutile TiO2. A 3D architecture has been demonstrated as an effective photoelectrode when employed in a DSC along with a metal-free organic dye (D149). Although the performance of HRT based devices was inferior to those of state-of-the-art commercial antase Dyesol-T paste, this study provided some important insights into rutile TiO2, and in particular its possible applications in DSCs. The difference in Jsc here is significantly less than in previous studies26. Charge transport is seen to be less of a problem than it was initially anticipated to be. Further investigations and comparison between rutile and anatase are ongoing, including looking into bi-layer rutile devices incorporating a less scattering front layer.

An energy conversion efficiency of 5.5% was achieved, which is superior to that of an analogous device using P25 (4.5%), and comparable to Dyesol-T (5.8%). The overall conversion efficiency 8.6% was achieved when HRT was used as the light scattering layer, a considerable improvement over commercial anatse Dyesol-T (~12 μm)/Dyesol-S (~4 μm) system (7.6%). The 3D rutile TiO2 and metal-free indoline sensitizer may present an alternative candidate with regard to producing high-performance DSCs.

Methods

Preparation of 3D hierarchical rutile TiO2 architectures (HRT)

Tetrabutyl titanate (Ti(OCH2CH2CH2CH3)4, 97%, TT, analytical reagent grade) and hydrochloric acid (37% HCl, analytical reagent grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and used without purification or additives. The typical experimental procedures are described as follows: firstly, 0.5 mL of TT was added dropwise into an amount of concentrated HCl under magnetic stirring. Then, the above solution was diluted by distilled water to meet a total volume of 25.5 mL under different HCl concentrations (1 M–8 M). After vigorously stirring for another 1.5 h and aging for 1 h, the whole mixture was transferred into a 45 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave and sealed. The hydrothermal synthesis was conducted at 150°C for 5 h in an electric oven. After ambient cooling to room temperature, the resultant powder was collected and centrifuged, rinsed with absolute ethanol repeatedly, and finally dried at 110°C under vacuum. The powders were named as HRT-1 to HRT-8, respectively, with the number representing the concentration (in M) of HCl used during synthesis.

Materials characterizations

The crystal phase of the 3D hierarchical TiO2 architectures were measured with a powder X-ray diffractometer (XRD, MMA, GBC Scientific Equipment LLC, Hampshire, IL, USA) with Cu Kα radiation. The morphology of the samples was examined by Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM, JSM-7500FA, JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) and High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM, JEM-2100F). Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas (SBET) were determined by using a nitrogen adsorption apparatus (Tristar 3030, Micromeritics Instrument Corporation), with all samples being degassed at 120°C overnight before measurement. Dye desorption was performed by dipping the sensitized sample into 0.4 M NaOH in methanol solution. Film thickness was measured with a Veeco Dektak 150 Surface Profiler. The light scattering properties of the samples were investigated by ultraviolet (UV)-visible light absorption/diffuse reflectance spectrometry (Shimadzu UV-3600) with integrating sphere attachment.

Preparation of TiO2 photoanodes

To prepare the DSC working electrodes, fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) glass (2.3 mm thick, 8 Ω/sq, Hartford Glass), used as current collector, was first cleaned with soapy water for 20 min, rinsed with distilled water, immersed in an ultrasonic bath in acetone and then again in ethanol for 30 min each. Following this, a dense TiO2 blocking layer was deposited on the clean FTO glass by spray pyrolysis of a solution of diluted titanium diisopropoxide bis(acetylacetonate), 75% in isopropanol (Aldrich), in absolute ethanol in the volume ratio of 1:9. Next, a layer of TiO2 paste was cast onto the FTO glass plates by a manual doctor-blade method. These pastes were produced as follows: 0.1 g of TiO2 powder was ground with a mixture of ethanol (10 mL), distilled water (10 mL), nitric acid (0.167 mL), polyethylene glycol solution (4 mL, 10 wt% in distilled water, MW = 100,000), and triton X-100 (one small drop) to form a slurry, and then the slurry was sonicated for 1 h in an ultrasonic bath and stirred for 2 h. A viscous white TiO2 paste was finally obtained. After a heating process (at 150°C for 10 min, at 325°C for 5 min, at 375°C for 5 min, at 450°C for 30 min, and then at 500°C for 15 min) to remove organic components and improve interparticle connectivity, the TiO2 films were soaked in 0.02 M aqueous titanium tetrachloride solution (TiCl4) at 70°C for 30 min, before being sintered again (500°C for 30 min). State-of-the-art commercial transparent titania anatase paste (18NR-T, denoted as Dyesol-T), and commercial reflector titania anatase paste (WER2-O, denoted as Dyesol-S), [both obtained from Dyesol (Australia)] were used for the references.

Fabrication of Dye-sensitized solar cells

The porous TiO2 films were immersed in a 0.5 mM D149 (1-material, Canada) dye solution in a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of acetonitrile (HPLC, Lab-scan) and tert-butanol (LR, Ajax Chemicals) overnight once their temperature decreased to approximately 110°C. The samples were then taken out of the dye bath, washed with acetonitrile, and dried. The working electrode and Pt counter electrode [produced using a pre-drilled piece of 2.3 mm FTO glass, coated with one drop of 10 mM platinic acid solution [H2PtCl6 (Sigma)] and heated to 400°C for 20 min] were assembled into a sandwich type cell and sealed with a spacer of 25 μm Surlyn (Solaronix). An I−/I3− organic solvent based electrolyte solution [50 mM iodine (Sigma), 0.6 M 1,2-dimethyl-3-propylimidazelium iodide (Solaronix), 0.1 M lithium iodide (Sigma) in methoxypropionitrile (Sigma)] was introduced via vacuum back-filling. The hole was sealed with a piece of aluminium foil-backed Surlyn.

Solar cell characterizations

Photocurrent density – voltage (J–V) curves were measured using a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter, a simulated 100 mW cm−2 air mass (AM) 1.5 light source (Oriel), and customized LabView software. The device area was masked with a metallic mask slightly larger than the active area. Incident photon-to-current quantum conversion efficiency (IPCE) was measured using a 300 W Xe lamp, a monocromator with sorting filters, focused to a spot with additional optics. The short circuit current response of the devices was recorded in 5 nm steps using a Keithley 2400 sourcemeter. The measured currents were referenced to a calibrated Si photodiode (PECCELL).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Projects (DP1096546). Dr. Andrew Nattestad would like to thank the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) for financial support. The authors would also like to thank the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) for access to equipment.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions J.L., A.N. and J.H.K. designed experiments. J.L. performed synthesis experiments and DSC measurements. Y.U.H. performed TEM. Z.S. supervised the synthesis experiment. J.L., A.N., L.W. and J.H.K. analysed the data. J.L., A.N., J.H.K. and S.X.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and contributed to revisions.

References

- O'Regan B. & Grätzel M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2 films. Nature 353, 737–740 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Wold A. Photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide (TiO2). Chem. Mat. 5, 280–283 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. & Mao S. S. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem. Rev. 107, 2891–2959 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavykin D. V., Friedrich J. M. & Walsh F. C. Protonated titanates and TiO2 nanostructured materials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv. Mater. 18, 2807–2824 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. & Lin Z. Freestanding TiO2 nanotube arrays with ultrahigh aspect ratio via electrochemical anodization. Chem. Mat. 20, 1257–1261 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Feng X. et al. Vertically aligned single crystal TiO2 nanowire arrays grown directly on transparent conducting oxide coated glass: synthesis details and applications. Nano Lett. 8, 3781–3786 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J. et al. Formation of highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells by hierarchical pore generation with nanoporous TiO2 spheres. Adv. Mater. 21, 3668–3673 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. & Aydil E. S. Growth of oriented single-crystalline rutile TiO2 nanorods on transparent conducting substrates for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 3985–3990 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye M., Xin X., Lin C. & Lin Z. High efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells based on hierarchically structured nanotubes. Nano Lett. 11, 3214–3220 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Xiong Y., Li Z. & Xie Y. Large-scale fabrication of TiO2 hierarchical hollow spheres. Inorg. Chem. 45, 3493–3495 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan T.-G. N. et al. A simple hydrothermal perparation of TiO2 nanomaterials using concentrated hydrochloric acid. J. Cryst. Growth. 312, 79–85 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Lin L. & He D. Phase and morphological transitions of titania/titanate nanostructures from an acid to an alkali hydrothermal environment. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 1659–1668 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu F. et al. Hierarchical TiO2 microspheres: synthesis, structural control and their applications in dye-sensitized solar cells. RSC Adv. 2, 11629–11637 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z. et al. Rational design of 3D dendritic TiO2 nanostructures with favorable architectures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19314–19317 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. & Cao G. Hierarchically structured photoelectrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 6769–6774 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tétreault N. & Grätzel M. Novel nanostructures for next generation dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 5, 8506–8516 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Beuvier T. et al. TiO2 (B) nanoribbons as negative electrode material for lithium ion batteries with high rate performance. Inorg. Chem. 49, 8457–8464 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. P., Lin S. Y., Lee Y. C. & Chen-Yang Y. W. High surface area electron prickle-like hierarchical anatase TiO2 nanofibers for dye-sensitized solar cell photoanodes. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 9875–9884 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Geng B., You J., Zhan F., Kong M. & Fang C. Controllable morphology evolution and photoluminescence of ZnSe hollow microspheres. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 11301–11306 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Rauber M. et al. Highly-ordered supportless three-dimensional nanowire networks with tunable complexity and interwire connectivity for device integration. Nano Lett. 11, 2304–2310 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. et al. One-step synthesis of monodisperse and hierarchically mesostructured silica particles with a thin shell. Langmuir 26, 13556–13563 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikoobakht B. & El-Sayed M. A. Preparation and growth mechanism of gold nanorods (NRs) using seed-mediated growth method. Chem. Mat. 15, 1957–1962 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Mor G. K., Varghese O. K., Paulose M. & Grimes C. A. Transparent highly ordered TiO2 nanotube arrays via anodization of titanium thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 1291–1296 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Li J. et al. Patterning of nanostructured cuprous oxide by surfactant-assisted electrochemical deposition. Cryst. Growth Des. 8, 2652–2659 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M. R., Martin S. T., Choi W. & Bahnemann D. W. Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 95, 69–96 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Park N.-G., Van de Lagemaat J. & Frank A. Comparison of dye-sensitized rutile-and anatase-based TiO2 solar cells. J. Phys.Chem. B 104, 8989–8994 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Feng X., Shankar K., Paulose M. & Grimes C. A. Tantalum-doped titanium dioxide nanowire arrays for dye-sensitized solar cells with high open-circuit voltage. Angew. Chem. 121, 8239–8242 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N.-G. et al. Dye-sensitized TiO2 solar cells: structural and photoelectrochemical characterization of nanocrystalline electrodes formed from the hydrolysis of TiCl4. J. Phys.Chem. B 103, 3308–3314 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Grätzel M. Conversion of sunlight to electric power by nanocrystalline dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 164, 3–14 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Nazeeruddin M. K., Splivallo R., Liska P., Comte P. & Grätzel M. A swift dye uptake procedure for dye sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 1456–1457 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazeeruddin M. K. et al. Combined experimental and DFT-TDDFT computational study of photoelectrochemical cell ruthenium sensitizers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 16835–16847 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazeeruddin M. K. et al. Engineering of efficient panchromatic sensitizers for nanocrystalline TiO2-based solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 1613–1624 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie W. H., Claeyssens F., Miura H. & Peter L. M. Characterization of solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells utilizing high absorption coefficient metal-free organic dyes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 1367–1375 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito S. et al. High-efficiency organic-dye-sensitized solar cells controlled by nanocrystalline-TiO2 electrode thickness. Adv. Mater. 18, 1202–1205 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Nazeeruddin M. K. et al. Acid-base equilibria of (2, 2′-bipyridyl-4, 4′-dicarboxylic acid) ruthenium (II) complexes and the effect of protonation on charge-transfer sensitization of nanocrystalline titania. Inorg. Chem. 38, 6298–6305 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto S., Fleury P. & Damen T. Raman Spectra of TiO2, MgF2, ZnF2, FeF2, and MnF2. Phys. Rev. 154, 522 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- Guo W. et al. Rectangular bunched rutile TiO2 nanorod arrays grown on carbon fiber for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4437–4441 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman P. & Perdok W. On the relations between structure and morphology of crystals. II. Acta Crystallogr. 8, 521–524 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Hartman P. & Perdok W. On the relations between structure and morphology of crystals. III. Acta Crystallogr. 8, 525–529 (1955). [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. J., Scanlon D. O. & Watson G. W. Small polarons in Nb-and Ta-doped rutile and anatase TiO2. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 5175–5178 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi K., Hosono E., Imai H., Kimura T. & Fujihara S. {111}-faceting of low-temperature processed rutile TiO2 rods. J. Cryst. Growth 293, 541–545 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Watson G., Oliver P. & Parker S. Computer simulation of the structure and stability of forsterite surfaces. Phys. Chem. Miner. 25, 70–78 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. J., Park S. D., Jeong Y. H. & Park S. Homogeneous precipitation of TiO2 ultrafine powders from aqueous TiOCl2 solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 82, 927–932 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hosono E., Fujihara S., Kakiuchi K. & Imai H. Growth of submicrometer-scale rectangular parallelepiped rutile TiO2 films in aqueous TiCl3 solutions under hydrothermal conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7790–7791 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar D., Ghosh C. K. & Chattopadhyay K. K. Morphology control of rutile TiO2 hierarchical architectures and their excellent field emission properties. CrystEngComm. 14, 2683–2690 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. et al. The electronic role of the TiO2 light-scattering layer in dye-sensitized solar cells. Z. Phys. Chem. 221, 319–328 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Moser J. E. & Grätzel M. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopic analysis of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 14945–14953 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Ito S. & Grätzel M. Characteristics of high efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 25210–25221 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi M., Sakamoto M., Jiu J., Ogata Y. & Isoda S. Determination of parameters of electron transport in dye-sensitized solar cells using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 13872–13880 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Lagemaat J., Benkstein K. D. & Frank A. J. Relation between particle coordination number and porosity in nanoparticle films: implications to dye-sensitized solar cells. The J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 12433–12436 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Benkstein K. D., Kopidakis N., Van de Lagemaat J. & Frank A. Influence of the percolation network geometry on electron transport in dye-sensitized titanium dioxide solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 7759–7767 (2003). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information