Abstract

The role of serum CYFRA 21-1 level in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains to be defined. To re-evaluate the impact of serum CYFRA 21-1 in NSCLC survival, we performed this meta-analysis. Databases were searched to identify relevant studies reported after the publication of a meta-analysis in 2004. Totally, 31 studies with 6394 patients were included in this meta-analysis. The pooled Hazard ratios (HRs) indicated that high CYFRA 21-1 level was associated with poor prognosis on overall survival (OS) in patients with NSCLC (HR = 1.60; 95%CI = 1.36–1.89; P < 0.001). The pooled HRs were 2.18 (95%CI = 1.70, 2.80; P = 0.347) for patients at stage I–IIIA and 1.47 (95%CI = 1.02, 2.11; P < 0.001) for stage IIIB–IV. When stratified by surgical intervention, pooled HRs were 1.94 (95%CI = 1.42–2.67; P < 0.001) for studies with surgery and 1.24 (95%CI = 0.79–1.95; P < 0.001) for studies without surgery. Significant associations were also found in the patients treated with EGFR-TKIs (HR = 1.83; 95%CI = 1.31–2.58; P = 0.011) and platinum-based regimen (HR = 1.53; 95%CI = 1.18–1.99; P = 0.001). Meta-analysis of CYFRA 21-1 related to PFS was performed and pooled HR was 1.41 (95%CI = 1.19–1.69; P < 0.001). Our results indicate that high level of serum CYFRA 21-1 is a negative prognostic indicator of patients with NSCLC.

Lung cancer remains the most frequent cause of cancer death globally. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of lung cancers1. Surgery is the most promising treatment modality for potential cure. However, even patients with stage I NSCLC suffer a 30% risk of relapse after resection2. In addition, a great majority of patients, approximately 80%, are diagnosed in advanced stages3. In spite of the improvements in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques on lung cancer over the past few decades, the prognosis is still poor, with an estimated survival of only 15% at 5 years4. In recent years, many independent clinical and biological prognostic factors for lung cancer have been reported, such as stage, performance status (PS), age, K-ras oncogene mutations, Ki-67 expression, p16 promoter hypermethylation and excision repair cross-complementing 1 (ERCC1) polymorphism5,6,7,8. Correct identification of molecular prognostic factors may contribute to a better understanding of cancer development, clinical outcome, and eventually facilitate the rational selection of therapeutic strategies.

CYFRA 21–1 is a fragment of cytokeratin (CK) 19 and CKs are the principal structural elements of the cytoskeleton of epithelial cells, including bronchial epithelial cells. CK19 is expressed in the unstratified or pseudostratified epithelium lining the bronchial tree, and been reported to be overexpressed in many lung cancer tissue specimens. The CYFRA 21–1 expression patterns in tissues are well-maintained even during the process of transformation of the tissue from normal to tumor tissue9,10. Many studies demonstrated high expression and diagnostic value of CYFRA 21–1 in NSCLC11. Also, some researches reported that CYFRA 21–1 expression was associated with metastatic lymph nodes, TNM stage, tumor size, and differentiation12. CYFRA 21-1 has been identified to be a sensitive biomarker in NSCLC. It was reported that the sensitivity of CYFRA 21-1 in diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma was 62%13. Following the fist identification of high serum CYFRA 21-1 level as a valuable prognostic marker in lung cancer patients in 199314, numerous studies have been performed to validate the result. A meta-analysis of the prognostic role of serum CYFRA 21-1 for NSCLC was reported in 200415. They analyzed the data from 1993 to 2001, and demonstrated that a high serum CYFRA 21-1 level was correlated with poor prognosis for NSCLC patients whatever the planned treatment. However, the result of the patients having undergone surgery only showed a trend of statistical significance. Furthermore, this meta-analysis had the following limitations: relatively short follow-ups, including a small number of accrued patients, and not providing detailed treatments for patients who did not undergo surgery.

Subsequently, many studies investigating the role of serum CYFRA 21-1 with more updated therapeutic strategies for NSCLC and larger numbers of accrued patients have been performed16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46. However, these studies yielded conflicting results. Therefore, we conducted an updated meta-analysis using data from these studies to reappraise the effect of serum CYFRA 21-1 on the prognosis in patients with NSCLC.

Results

Characteristics of eligible studies

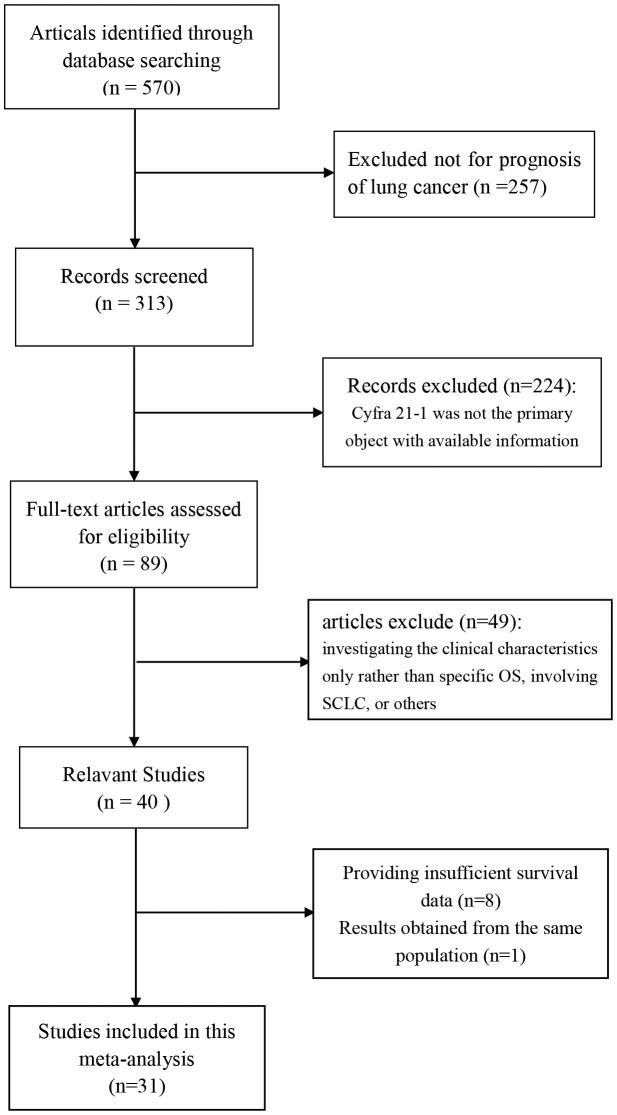

After deleting the duplications, a total of 570 potentially relevant publications were collected after initial search. Among these, 313 articles related to the prognosis of lung cancer were reserved. Then 89 studies primarily researching the CYFRA 21-1 level were selected in full text for further screening after reviewing the abstracts. 49 studies were excluded for only investigating the clinical characteristics rather than specific OS, involving small cell lung cancer (SCLC), or other out of the scope according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, consequently leaving 40 available for further review. After carefully reading, 31 studies, with a total number of 6394 patients were identified in this meta-analysis (Figure 1). Some studies reported two endpoints, and they were analyzed separately. The main characteristics of the evaluable studies were listed in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flow chart of studies in the analysis.

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | Country | Ethnicity | Surgery | Chemotherapy | TNM | Design | N | Follow-up(month) | Biomarkers | Method | Cutoff | High/low | HR-E | AHR | ALL | AUL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin | 2012 | China | Asian | Yes | PB/A | IB-IIIA | R | 169 | 53(3–66) | OS | ECLIA | 3.30 | 63/106 | HR | 1.70 | 1.19 | 2.44 |

| Tanaka | 2013 | Japan | Asian | NA | TKI/M | IIIB/IV | R | 160 | 32.5(23.3–44.6) | PFS/OS | ECLIA | 2.00 | 83/77 | HR | 1.10 | 0.85 | 1.41 |

| Park | 2013 | Korea | Asian | Yes | NA | I–III | R | 298 | 43.3(0.5–95.6) | PFS/OS | ECLIA | 1.95 | 114/184 | HR | 1.10 | 1.01 | 1.20 |

| Trapé | 2012 | Spain | Caucasion | No | PB/M | IIIA–IV | P | 137 | NA | OS | ECLIA | 3.30 | 91/46 | HR | 2.21 | 1.40 | 2.83 |

| Edelman | 2012 | USA | Mixed | NA | PB/NA | IIIB/IV | P | 88 | NA | PFS/OS | ECLIA | 4.18 | NA | SC | 1.68 | 1.33 | 2.11 |

| Jung | 2011 | Korea | Asian | NA | TKI/M | IIIB/IV | R | 123 | NA | PFS/OS | ECLIA | 3.30 | 64/59 | HR | 2.76 | 1.38 | 5.53 |

| Cedrés | 2011 | Spain | Caucasion | NA | NA | III–IV | R | 183 | 9.7(1–126) | PFS/OS | IRMA | 3.30 | 119/64 | SC | 1.52 | 1.06 | 2.20 |

| Hanagiri | 2011 | Japan | Asian | Yes | PB/A | I | R | 341 | 42 | OS | IRMA | 2.00 | 145/196 | HR | 2.57 | 1.21 | 5.44 |

| Ma | 2011 | China | Asian | NA | NA | I | R | 153 | 26(2–121) | OS | ECLIA | 3.30 | 41/112 | HR | 9.81 | 1.64 | 58.67 |

| Jin | 2010 | China | Asian | No | PB/NA | IIIB/IV | R | 111 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.50 | 47/64 | HR | 1.68 | 1.05 | 2.69 |

| Takahashi | 2010 | Japan | Asian | NA | NA | I–IV | R | 1202 | NA | OS | CLEIA | 18.00 | NA | HR | 2.02 | 1.14 | 3.58 |

| Petris | 2011 | Sweden | Caucasion | NA | NA | I–IV | NA | 174 | NA | OS | ELISA | 6.00 | NA | HR | 0.80 | 0.73 | 1.32 |

| Tomita | 2010 | Japan | Asian | Yes | NA | I–III | R | 291 | 60.7–141.7 | OS | NA | 2.40 | 58/233 | HR | 1.57 | 1.29 | 1.89 |

| Nisman | 2009 | Israel | Asian | No | NA | IIIA–IV | P | 88 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.20 | 60/28 | RR | 1.80 | 1.10 | 2.80 |

| Chen | 2010 | China | Asian | No | TKI/M | III–IV | R | 122 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.30 | 49/73 | HR | 1.78 | 1.19 | 2.65 |

| Chakra | 2008 | France | Caucasion | NA | NA | I–IV | P | 451 | NA | OS | IRMA | 3.60 | 224/227 | HR | 1.50 | 1.20 | 1.86 |

| Jacot | 2008 | France | Caucasion | NA | NA | I–IV | P | 289 | 20.8(2.5–34.1) | OS | IRMA | 3.60 | 92/197 | HR | 2.30 | 1.52 | 3.49 |

| Ishikawa | 2008 | Japan | Asian | NA | TKI/M | IIIB/IV | R | 65 | 8.3(1.1–37.9) | PFS/OS | ECLIA | 2.80 | 48/17 | HR | 1.97 | 0.91 | 4.27 |

| Nisman | 2008 | Israel | Asian | No | PB/Mix | IIIA–IV | P | 60 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.20 | 43/37 | RR | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.90 |

| Hisashi | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Yes | NA | I–IV | R | 101 | 73 | OS | CLEIA | 3.50 | 6/95 | RR | 9.79 | 2.24 | 42.80 |

| Matsuoka | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Yes | NA | I | R | 256 | 35.5(3.7–75.5) | OS | ELISA | 2.80 | 35/221 | SC | 2.92 | 2.25 | 6.84 |

| Mizuguchi | 2007 | Japan | Asian | Yes | NA | I–IV | R | 272 | NA | OS | CLEIA | 2.00 | 149/123 | HR | 2.42 | 1.99 | 2.86 |

| Barle'si | 2005 | France | Caucasion | NA | TKI/NA | IIIB/IV | P | 51 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.50 | 13/38 | HR | 2.45 | 1.13 | 5.29 |

| Muley | 2004 | Germany | Caucasion | Yes | NA | I | R | 153 | NA | OS | ELISA | 3.30 | NA | HR | 2.16 | 1.08 | 4.29 |

| Barlesi | 2004 | France | Caucasion | No | PB/M | IIIB/IV | P | 264 | 9(1–77) | OS | ELISA | 3.50 | 138/126 | HR | 1.30 | 1.06 | 1.78 |

| Trapé | 2003 | Spain | Caucasion | No | PB/NA | IIIA–IV | P | 48 | NA | OS | ECLIA | 3.60 | NA | HR | 1.75 | 0.93 | 3.65 |

| Kulpa | 2002 | Poland | Caucasion | NA | NA | I–IV | NA | 200 | NA | OS | ECLIA | 3.60 | 127/73 | HR | 1.31 | 0.92 | 1.87 |

| Reinmuth | 2002 | Germany | Caucasion | Yes | NA | I–IIIA | P | 66 | 42(NA-86) | OS | ELISA | 3.57 | 23/43 | SC | 2.80 | 0.98 | 7.99 |

| Ono | 2013 | Japan | Asian | No | NA | IIIB/IV | R | 284 | NA | OS | CLEIA | 2.20 | 134/150 | HR | 0.43 | 0.31 | 0.59 |

| Ondrej F | 2014 | Czech | Caucasion | NA | TKI/M | IIIB/IV | R | 144 | NA | OS/PFS | ELISA | 2.50 | 83/61 | HR | 2.17 | 1.48 | 3.19 |

| Monik | 2014 | NA | Gaussian | Yes | None | I–IV | P | 50 | 72.5(4–108) | OS | ELISA | 2.10 | 0.45 | SC | 1.00 | 0.45 | 2.21 |

HR-E: HR Estimate; R: retrospective; P: prospective; NA: not available; PB/A: Platinum-based/adjuvant chemotherapy; PB/M: Platinum-based/metastatic chemotherapy; PB/mix: Platinum-based/adjuvant chemotherapy and metastatic chemotherapy; TKI/M: TKI/metastatic chemotherapy; TKI/Mix: TKI/adjuvant and metastatic chemotherapy; SC: survival curve; AHR: adjusted hazard ratio; ALL: adjusted lower limit; AUL: adjusted upper limit; ECLIA: electrochemiluminescence immunoassay; ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; CLEIA: chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay; IRMA: immunoradiometric assay.

In the present meta-analysis, statistical calculations for OS were performed in 31 studies. Sample size of studies ranged from 48 to 1202. 17 studies were performed in Asian, 13 studies were in Caucasian, and one study was in mixed populations. 6 studied NSCLC patients at stage I–IIIA, 9 studied patients at stage IIIB–I, and 15 studied the wide range of stage I–IV. 12 were conducted prospectively, 17 were performed retrospectively, and 2 were not available. The numbers of studies reported all of the patients with surgery and without surgery were 9 and 9, respectively. 7 studies including 1061 patients were involved in PFS calculation. The detailed information of them was described in Table 1.

Serum CYFRA 21-1 was dichotomized into high and low levels, and different cut-off value was selected in each study. Most of the studies utilized the manufacturer's instructions, some applied the median or mean levels as cut-off values, and the remaining studied defined the value by themselves or a ROC curve.

Main results

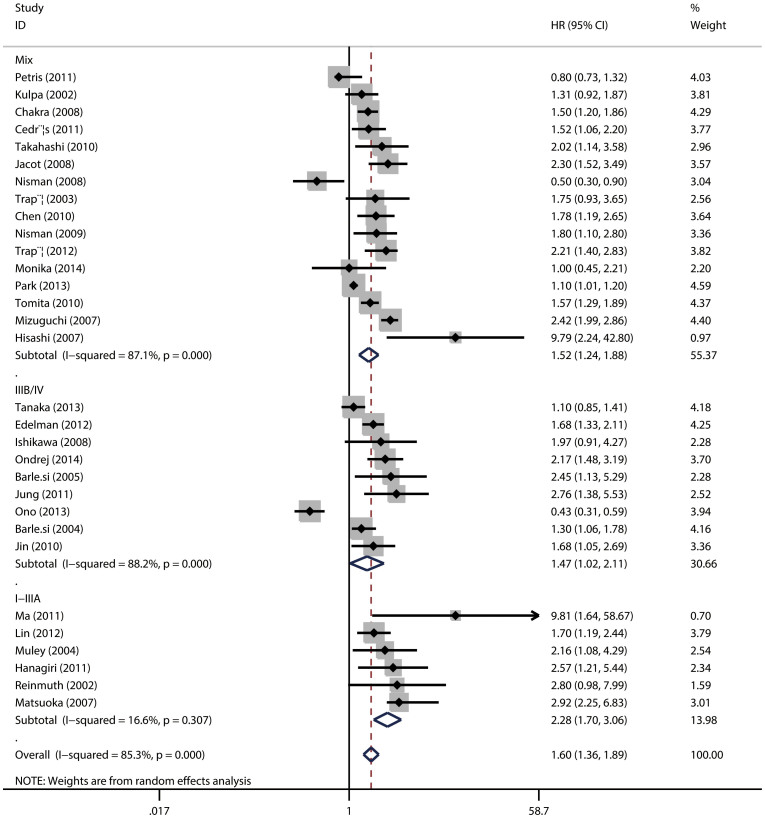

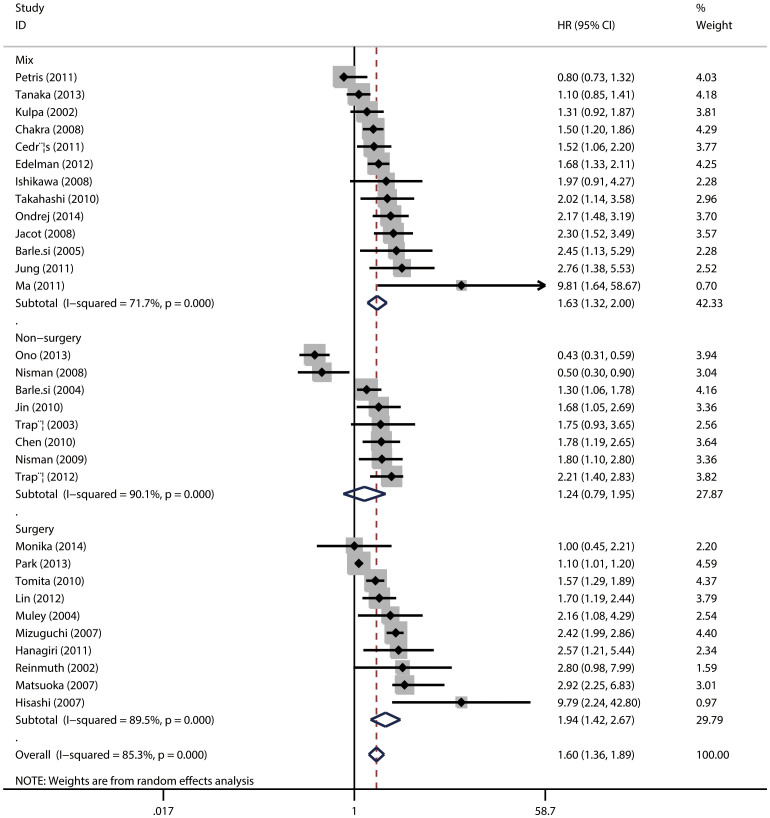

The main results of the meta-analysis were listed in Table 2. Among the 31 trials eligible for assessing the relationship between CYFRA 21-1 and OS, the pooled HR was 1.60 (95%CI = 1.36–1.89; P < 0.001) (Figure 2), indicating that high serum CYFRA 21-1 level predicted poor OS for NSCLC. In the subgroup analysis by TNM stage, for patients with NSCLC at stage I–IIIA (resected tumor), the pooled HRs were 2.18 (95%CI = 1.70, 2.80; P = 0.347) and for stage IIIB–IV (unresectable disease), the pooled HRs were 1.47 (95%CI = 1.02, 2.11; P < 0.001) while for mixed stage I–IV, HRs were 1.52 (95%CI = 1.24, 1.88; P < 0.001), indicating a significant association between high serum lever of CYFRA 21-1 and poor clinical outcome (Figure 2). Then to evaluate the prognostic roles in surgical intervention, we divided the studies into surgery group and non-surgery group and found a pool HR of 1.94 (95%CI = 1.42, 2.67; P < 0.001) for surgery group and 1.24 (95%CI = 0.79–1.95; P < 0.001) for non-surgery group (Figure 3).

Table 2. Main results of the meta-analysis.

| N.of studies | N. of patients | HR(95%CIs) | Heterogeneity test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | I-squared | P-value | ||||

| OS | ||||||

| Overall | 31 | 6394 | 1.60(1.36,1.89) | 204.53 | 85.30% | <0.001 |

| Stage | ||||||

| I–IIIA | 6 | 1138 | 2.18(1.70,2.80) | 5.99 | 16.60% | 0.307 |

| IIIB–IV | 9 | 1290 | 1.47(1.02,2.11) | 68.04 | 88.20% | <0.001 |

| Mix(I–IV) | 16 | 3966 | 1.52(1.24,1.88) | 116.06 | 87.10% | <0.001 |

| Surgical intervention | ||||||

| Surgery | 10 | 1997 | 1.94(1.42,2.67) | 85.90 | 89.50% | <0.001 |

| Non-surgery | 8 | 1114 | 1.24(0.79,1.95) | 70.54 | 90.10% | <0.001 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| EGFR-TKI | 6 | 665 | 1.83(1.31,2.58) | 14.84 | 66.30% | 0.011 |

| Platinum-based | 8 | 1218 | 1.53(1.18,1.99) | 24.67 | 71.60% | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian | 17 | 4096 | 1.62(1.25,2.09) | 160.26 | 90.00% | <0.001 |

| Caucasian | 13 | 2210 | 1.60(1.31,1.95) | 36.48 | 67.10% | <0.001 |

| Sample size | ||||||

| Small | 20 | 2246 | 1.66(1.35,2.03) | 68.62 | 72.30% | <0.001 |

| Large | 11 | 4148 | 1.53(1.16,2.00) | 130.45 | 92.30% | <0.001 |

| Study design | ||||||

| Prospective | 11 | 1542 | 1.58(1.27,1.96) | 30.18 | 66.90% | 0.001 |

| Retrospective | 18 | 4478 | 1.75(1.38,2.22) | 155.27 | 89.10% | <0.001 |

| PFS | ||||||

| Overall | 7 | 1061 | 1.41(1.19,1.69) | 24.54 | 75.60% | <0.001 |

OS: overall survival; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; PFS: progression-free survival.

Figure 2. The association between serum CYFRA 21-1 and overall survival of NSCLC stratified by TNM stage.

Figure 3. The association between serum CYFRA 21-1 and overall survival of NSCLC stratified by surgical intervention.

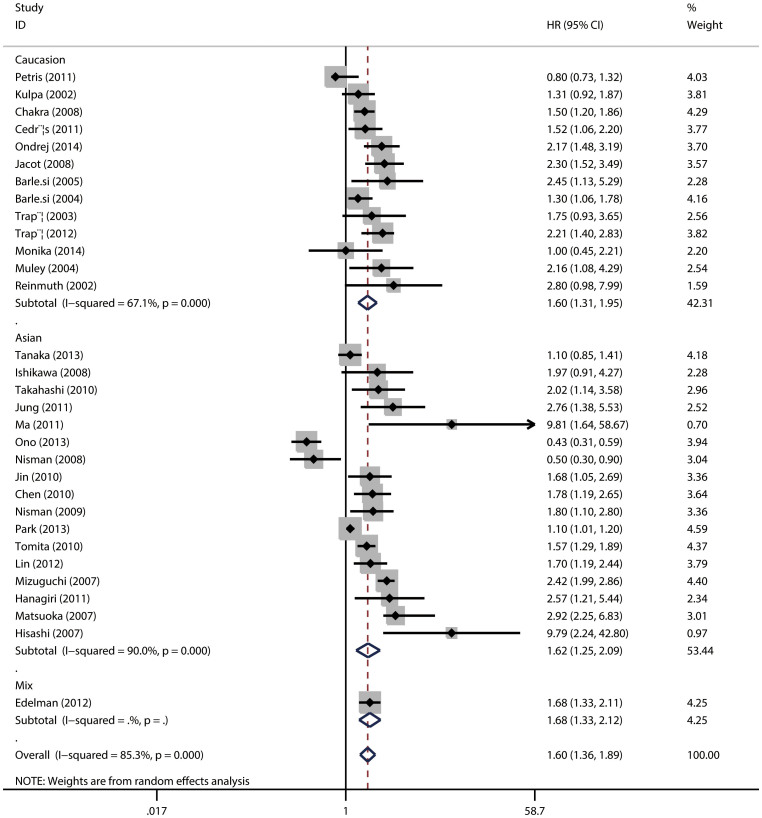

When stratified by ethnicity, a pooled HR was 1.62 (95%CI = 1.25–2.09; P < 0.001) for Asians and 1.60 (95%CI = 1.31–1.95; P < 0.001) for Caucasians (Figure 4), favoring the association between high serum CYFRA 21-1 level and poor prognosis. In the subgroup analysis according to study design, a significant link was also found in prospective studies 1.58 (95% CI = 1.27–1.96, P = 0.001) and retrospective studies 1.75 (95% CI = 1.38–2.22, P < 0.001), respectively (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 4. The association between serum CYFRA 21-1 and overall survival of NSCLC stratified by ethnicity.

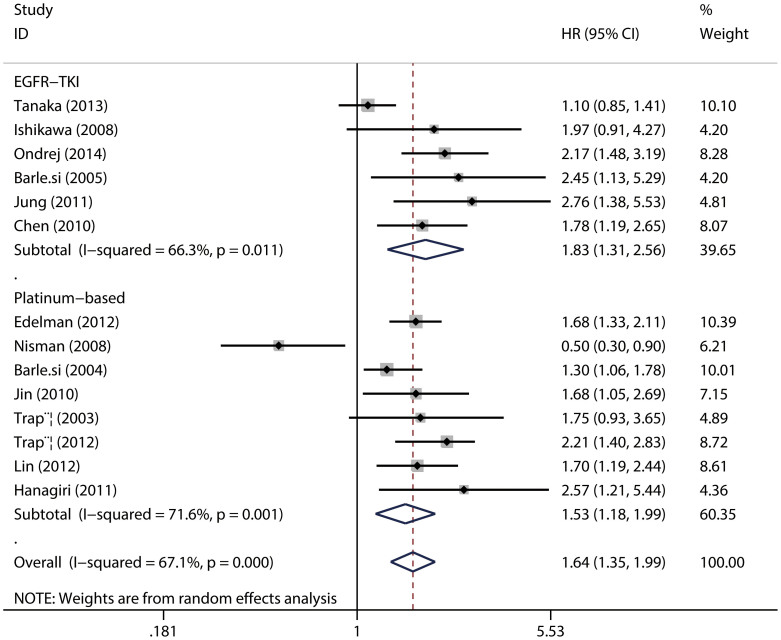

When sub-grouped by the chemotherapeutic regimens, the pooled HRs were 1.83 (95%CI = 1.31–2.58; P = 0.011) for studies using EGFR-TKIs, and 1.53 (95%CI = 1.53–1.99; P = 0.001) for studies applying platinum-based chemotherapy (Figure 5), again, indicating a relationship between high serum CYFRA 21-1 level and poor outcome for NSCLC.

Figure 5. The association between serum CYFRA 21-1 and overall survival of NSCLC stratified by chemotherapy regimen.

Meta-analysis of PFS was conducted in 7 studies. The pooled HR was 1.41 (95%CI = 1.19–1.69; P < 0.001). Statistically significant effect on PFS was found for serum CYFRA 21-1.

We also performed sensitivity analyses by repeatedly deleting the single studies each time from pooled analysis to examine the stability and reliability of meta-analysis results. In our analysis, the omission of individual studies did not materially alter the results because the recalculated ORs and 95%CIs were not quantitatively changed, suggesting that the results were robust and convincing (Supplementary Fig. S2, S3).

Publication bias

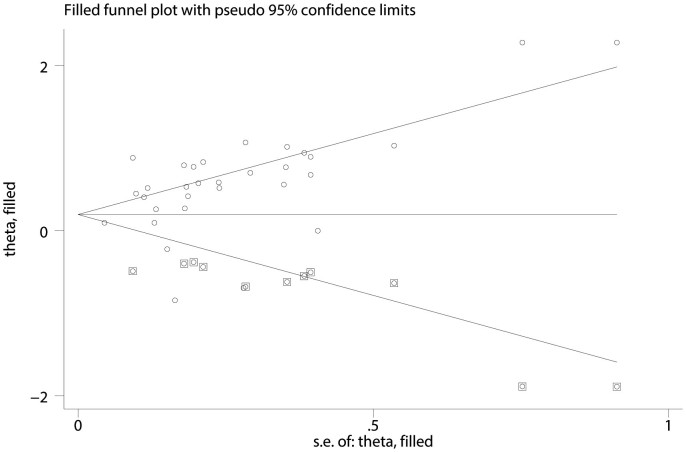

Publication bias was assessed by Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test. Publication bias was detected (P = 0.144 for Begg's test but P = 0.03 for Egger's test) for pooled OS. Thus, a trim and fill method was utilized and pooled ORs were recalculated with hypothetically non-published studies to evaluate the asymmetry in the funnel plot47 (Figure 6). The recalculated ORs for OS did not change significantly (HR = 1.27; 95% CI = 1.075–1.493; P < 0.001), indicating the stability of the results. However, significant publication bias was not discovered among the studies regarding PFS (P = 0.368 for Begg's test).

Figure 6. Funnel plot for OS, adjusted with trim and fill method Circles stand for included studies; diamonds stand for presumed missing studies.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, we demonstrated, for the first time, that high serum CYFRA 21-1 level was an indicator of poor prognosis for NSCLC using updated data. Notably, our meta-analysis included three times more patients than the previously reported one15, and the studies employed more updated therapeutic regimen and patients with longer follow-ups. As a result, we were able to show a more plausible result.

In this meta-analysis, we identified 31 eligible studies including 6394 patients and concluded that high serum CYFRA 21-1 level was a poor prognostic indicator for OS and PFS. For different pathological TNM stage, high serum CYFRA 21-1 level was associated with poor clinical outcome of NSCLC patients. Thus, high level of serum CYFRA 21-1 might be a negative prognostic biomarker in NSCLC patients with resected tumor or with unresectable disease. This link was observed in surgery subgroups. Notably, we verified the poor prognostic role of high serum CYFRA 21-1 level in the patients who had undergone surgery (HR = 1.94; 95%CI = 1.42–2.67; P < 0.001), while the previous meta-analysis only indicated a trend towards statistical significance (HR = 1.41, 95% CI = 0.99–2.03, P = 0.055). However, for patients who did not undergo surgery, the HR was 1.24 (95%CI = 0.79–1.95; P < 0.001) while the previous meta-analysis showed high serum CYFRA 21-1 level predicted poor survival (HR = 1.78; 95%CI = 1.54–2.07, P < 0.001) in the first year of follow-up15.

We also found that high serum CYFRA 21-1 level was a poor prognostic factor for patients treated with EGFR-TKIs or platinum-based regimen. Platinum-based chemotherapy could improve survival and has become the standard chemotherapy for years48,49, however, the efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy varies among individuals, with a response rate of 26%–60%50. Various tumor markers have been studied in terms of their prognostic or predictive roles in NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy8,51,52,53,54. However, to date, no serum maker is currently recommended for routine clinical practice in prognosis of NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Based on our findings, serum CYFRA 21-1 might be a promising biomarker. EGFR mutations have been reported to be the most important prediction factor for patients treated with EGFR-TKIs55. Unfortunately, it is not feasible to obtain an adequate EGFR mutational analysis. Therefore, it is important to identify easily acquired clinical parameters that can serve as surrogate markers for EGFR mutants. Our results suggested that serum CYFRA 21-1 might play such a role in the prediction and prognosis of advanced NSCLC treated with EGFR-TKIs. Notably, this was the firstly pooled analysis to verify the prognostic role of serum CYFRA 21-1 in the NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy or EGFR-TKIs. In consideration of the relatively small sample size, large scale prospective studies are needed to further confirm the results.

The sub-group analyses by ethnicity and study design yielded the same results, further indicating the poor prognosis role of high serum CYFRA 21-1 level in NSCLC.

Attention must be paid to the relatively large heterogeneity among trials. Meta-regression was conducted by ethnicity, surgical intervention, chemotherapy, detective method, cutoff, study design, and sample size. However, none of them was found to be the sources of heterogeneity. In fact, many other factors may also be the potential source of heterogeneity, such as gender, age, and life styles of patients and so on. Due to lack of detailed data, we had to give up performing a meta-regression utilizing these variables. Publication bias is significant threat to the reliability of the results of a meta-analysis. Unfortunately, we did find publication bias by Begg's funnel plot and Egger's test. Then a trim and fill method was adopted to recalculate the adjusted ORs and the results did not change significantly, indicating the stability of the statistic analyses47.

Several limitations have to be noted in relation to this meta-analysis. First, all our analyses were based on abstracted data and not on individual patient data (IPD). It was commonly acknowledged that an IPD-based meta-analysis would reproduce more reliable estimation compared with one based on abstracted data56, while an IPD-based meta-analysis is a time-consuming effort, especially when some studies without high quality57. Second, several HRs were obtained based on the survival curves, which might have biased our results. Third, cutoff values were different among the studies. Finally, the publication bias and heterogeneity in the meta-analysis may partly lessen its statistical power. However, these problems are almost inevitable in a meta-analysis.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis, based on an updated data, found a significant prognostic value of serum CYFRA 21-1. High serum CYFRA 21-1 level is correlated with poor OS and PFS in NSCLC, which might provide a simple and practical method to predict the outcome of NSCLC patients. Interestingly, serum CYFRA 21-1 is also related to the OS in the NSCLC patients treated with EGFR-TKIs or platinum-based regimen. But the sample size is relatively small, and more investigations are needed to identify its prognostic role in this part of NSCLC patients.

Methods

Search strategy

To update the data, we intended to exclude the studies accrued in the previous meta-analysis published in 200415. Therefore, only those studies published after January 1, 2002, were eligible. We conducted a computerized literature search of Embase, Web of Science, PubMed and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) to identify all the studies that studied the association of serum CYFRA 21-1 lever and lung cancer. The combination of the following key words were used as search terms separately and in combination: “CYFRA 21-1”, “cytokeratin 19”, “non-small cell lung cancer”, “NSCLC”, “prognosis”, “survival”, and “outcome”. Last search was updated on January 08, 2015. The references of all publications and reviews were manually searched to identify potentially relevant studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in this meta-analysis, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) trials had to deal with NSCLC; (2) investigating the association between serum CYFRA 21-1 level and prognosis; (3) CYFRA 21-1 was clarified as “high” and “low” value; (4) published as a full paper in English for data extraction; and (5) including enough blood sample. To avoid duplication of data, only the most complete and recent study was included. Titles and abstracts of searching records were screened and full text papers were further evaluated to confirm the eligibility. According to the inclusion criteria, two reviewers (Youtao Xu and Mantang Qiu) extracted eligible studies independently, and disagreement between the two reviewers was settled by discussing with the third reviewer (Lei Xu).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (Xu and Qiu) determined study eligibility independently in order to avoid selection bias in the data abstraction process. The following information was culled from each study: the first author, publication year, country where the research was performed, ethnicity, number of patients, histology, stage, detective method, cutoff, study design, and survival data. The primary endpoint was OS. The studies utilizing PFS were also analyzed.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the predictive ability of high serum CYFRA 21-1 level on survival of NSCLC, the hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of OS and PFS were extracted from eligible studies. If these data were not available, the HRs and CI were calculated according to Tierney' methods58. The heterogeneity among studies was evaluated using the Cochran Q and I2 test: for the Q test, a P < 0.1 was considered statistically significant59. For I2 test, a value >50% was considered a severe heterogeneity60, then the random-effects model (based on DerSimonian-Laird method) was used61; otherwise, the fixed-effects model (based on Mantel-Haenszel method) was applied. Meta-regression was performed to assess the sources of heterogeneity by ethnicity, surgical intervention, chemotherapy, detective method, cutoff, study design, and sample size (studies with less 200 participants were categorized as “small”, and studies with more than 200 participants were categorized as “large”). Between study, variance Tau-squared (τ2) value was used to evaluate the degree of heterogeneity and describe the extent of heterogeneity explained62. Sensitivity analysis was performed to examine the stability of the pooled results. Publication bias was evaluated by a funnel plot with Egger's test and Begg's test, and a P < 0.05 was considered significant63. All statistical analyses were calculated with STATA software (version 12.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas USA). And all P values were two-side.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This study is founded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (81372321 to L. Xu; 81201830 and 81472200 to R. Yin), Natural Science Foundation for High Education of Jiangsu Province (13KJB320010 to R. Yin), and Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (BL2012030 to L. Xu).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: Y.T.X., L.X., M.T.Q., R.Y., L.X. and J.W. Performed the experiments: Y.T.X., L.X., J.W., M.T.Q., Q.Z. and R.Y. Analyzed the data: Y.T.X., L.X. and M.T.Q. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Y.T.X., J.W., M.T.Q., R.Y. and L.X. Wrote the paper: Y.T.X., L.X., M.T.Q., J.W. and R.Y. Access to full-text articles: L.X. and J.W.

References

- Spira A. Ettinger DS. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer. N Engl J Med 350, 379–392 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstraw P. et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol 2, 706–714 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A. et al. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin 57, 43–66 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A. et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 59, 225–249 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huncharek M., Muscat J. & Geschwind J. F. K-ras oncogene mutation as a prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer: a combined analysis of 881 cases. Carcinogenesis 20, 1507–1510 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. et al. Ki-67 expression and patients survival in lung cancer: systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 91, 2018–2025 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou-Qian Z. et al. The prognostic value of epigenetic silencing of p16 gene in NSCLC patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 8, e54970 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. Z. et al. Predictive value of ERCC1 and XPD polymorphism in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer receiving platinum-based chemotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oncol 28, 315–321 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastel D., Ramaioli A., Cornillie F. & Thirion B. CYFRA 21-1, a sensitive and specific new tumour marker for squamous cell lung cancer. Report of the first European multicentre evaluation. CYFRA 21-1 Multicentre Study Group. Eur J Cancer 30A, 601–606 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broers J. L. et al. Cytokeratins in different types of human lung cancer as monitored by chain-specific monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Res 48, 3221–3229 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu X. Y. et al. Diagnostic values of SCC, CEA, Cyfra21-1 and NSE for lung cancer in patients with suspicious pulmonary masses: a single center analysis. Cancer Biol Ther 11, 995–1000 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Song I. H., Yang H. C., Kim K. & Jheon S. Predictive factors for node metastasis in patients with clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg, 96, 239–245 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieber P. et al. CYFRA 21-1. A new marker in lung cancer. Cancer 72, 707–713 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J. L. et al. Serum fragment of cytokeratin subunit 19 measured by CYFRA 21-1 immunoradiometric assay as a marker of lung cancer. Cancer Res 53, 61–66 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol J. L. et al. CYFRA 21-1 is a prognostic determinant in non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a meta-analysis in 2063 patients. Br J Cancer 90, 2097–2105 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono A. et al. Prognostic impact of serum CYFRA 21-1 in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 13, 354 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. et al. Cytokeratin 19 fragment predicts the efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitor in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring EGFR mutation. J Thorac Oncol 8, 892–898 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y. et al. Preoperative serum CYFRA 21-1 level as a prognostic factor in surgically treated adenocarcinoma of lung. Lung Cancer 79, 156–160 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trape J. et al. A prognostic score based on clinical factors and biomarkers for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Biol Markers 27, e257–262 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman M. J. et al. CYFRA 21-1 as a prognostic and predictive marker in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in a prospective trial: CALGB 150304. J Thorac Oncol 7, 649–654 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 levels in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib or erlotinib. Exp Ther Med 2, 685–693 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedres S. et al. Serum tumor markers CEA, CYFRA21-1, and CA-125 are associated with worse prognosis in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Clin Lung Cancer 12, 172–179 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanagiri T. et al. Preoperative CYFRA 21-1 and CEA as prognostic factors in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 74, 112–117 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Shen L., Qian N. & Chen K. The prognostic values of CA125, CA19.9, NSE, AND SCC for stage I NSCLC are limited. Cancer Biomark 10, 155–162 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin B., Huang A. M., Zhong R. B. & Han B. H. The value of tumor markers in evaluating chemotherapy response and prognosis in Chinese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chemotherapy 56, 417–423 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H. et al. Optimal cutoff points of CYFRA21-1 for survival prediction in non-small cell lung cancer patients based on running statistical analysis. Anticancer Res 30, 3833–3837 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Petris L. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic role of plasma levels of two forms of cytokeratin 18 in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer 47, 131–137 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita M., Shimizu T., Ayabe T., Yonei A. & Onitsuka T. Prognostic significance of tumour marker index based on preoperative CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 30, 3099–3102 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisman B. et al. The diagnostic and prognostic value of ProGRP in lung cancer. Anticancer Res 29, 4827–4832 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Luo X., Zhang J., Lu Y. & Luo R. Elevated serum levels of TPS and CYFRA 21-1 predict poor prognosis in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with gefitinib. Med Oncol 27, 950–957 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakra M. et al. Circulating serum vascular endothelial growth factor is not a prognostic factor of non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 3, 1119–1126 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacot W. et al. Quality of life and comorbidity score as prognostic determinants in non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Ann Oncol 19, 1458–1464 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa N. et al. Usefulness of monitoring the circulating Krebs von den Lungen-6 levels to predict the clinical outcome of patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer treated with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Int J Cancer 122, 2612–2620 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisman B. et al. Prognostic role of serum cytokeratin 19 fragments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: association of marker changes after two chemotherapy cycles with different measures of clinical response and survival. Br J Cancer 98, 77–79 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H. et al. Preoperative CYFRA 21-1 levels as a prognostic factor in c-stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 32, 648–652 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka K., Sumitomo S., Nakashima N., Nakajima D. & Misaki N. Prognostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA21-1 in patients with pathological stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 32, 435–439 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuguchi S. et al. Clinical value of serum cytokeratin 19 fragment and sialyl-Lewis x in non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 83, 216–221 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlesi F. et al. CYFRA 21-1 level predicts survival in non-small-cell lung cancer patients receiving gefitinib as third-line therapy. Br J Cancer 92, 13–14 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muley T., Dienemann H. & Ebert W. CYFRA 21-1 and CEA are independent prognostic factors in 153 operated stage I NSCLC patients. Anticancer Res 24, 1953–1956 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlesi F. et al. Prognostic value of combination of Cyfra 21-1, CEA and NSE in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Respir Med 98, 357–362 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trape J., Buxo J., Perez de Olaguer J. & Vidal C. Tumor markers as prognostic factors in treated non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 23, 4277–4281 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulpa J., Wojcik E., Reinfuss M. & Kolodziejski L. Carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, CYFRA 21-1, and neuron-specific enolase in squamous cell lung cancer patients. Clin Chem 48, 1931–1937 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinmuth N. et al. Prognostic impact of Cyfra21-1 and other serum markers in completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 36, 265–270 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. F., Wang X. D., Sun D. Q., Li Z. & Bai Y. High Serum CEA and CYFRA21-1 Levels after a Two-Cycle Adjuvant Chemotherapy for NSCLC: Possible Poor Prognostic Factors. Cancer Biol Med 9, 270–273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiala O. et al. Predictive role of CEA and CYFRA 21-1 in patients with advanced-stage NSCLC treated with erlotinib. Anticancer Res 34, 3205–3210 (2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szturmowicz M. et al. Prognostic value of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) and cytokeratin 19 fragments (Cyfra 21-1) but not carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in surgically treated patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 82, 422–429 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S. & Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56, 455–463 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister D. G. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology treatment of unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer guideline: update 2003. J Clin Oncol, 22, 330–353 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger D. S. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 4, 548–582 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl A. & Falk S. Meta-analysis of single agents in the chemotherapy of NSCLC: what do we want to know? Br J Cancer 84, 1143–1145 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. P., Shen H., Liu L. X. & Shu Y. Q. Association of ERCC1-C118T and -C8092A polymorphisms with lung cancer risk and survival of advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy: A pooled analysis based on 39 reports. Gene 526, 265–274 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiseo M. et al. ERCC1/BRCA1 expression and gene polymorphisms as prognostic and predictive factors in advanced NSCLC treated with or without cisplatin. Br J Cancer 108, 1695–1703 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. et al. VCP gene variation predicts outcome of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer platinum-based chemotherapy. Tumour Biol 34, 953–961 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. et al. Predictive value of XRCC1 gene polymorphisms on platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res 18, 3972–3981 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok T. S. et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 361, 947–957 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart L. A. & Parmar, M. K. Meta-analysis of the literature or of individual patient data: is there a difference? Lancet 341, 418–422 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Guetz G. et al. Microvessel density and VEGF expression are prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis of the literature. Br J Cancer 94, 1823–1832 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney J. F., Stewart L. A., Ghersi D., Burdett S. & Sydes M. R. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 8, 16 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J., Ioannidis J. P. & Schmid C. H. Quantitative synthesis in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 127, 820–826 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. & Thompson S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21, 1539–1558 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7, 177–188 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. G. & Higgins J. P. How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Stat Med 21, 1559–1573 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M., Davey Smith G., Schneider M. & Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information