Abstract

The nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase, focal adhesion kinase (FAK, also known as PTK2), is a key mediator of signal transduction downstream of integrins and growth factor receptors in a variety of cells, including endothelial cells. FAK is upregulated in several advanced-stage solid tumors and has been described to promote tumor progression and metastasis through effects on both tumor cells and stromal cells. This observation has led to the development of several FAK inhibitors, some of which have entered clinical trials (GSK2256098, VS-4718, VS-6062, VS-6063, and BI853520). Resistance to chemotherapy is a serious limitation of cancer treatment and, until recently, most studies were restricted to tumor cells, excluding the possible roles performed by the tumor microenvironment. A recent report identified endothelial cell FAK (EC-FAK) as a major regulator of chemosensitivity. By dysregulating endothelial cell–derived paracrine (also known as angiocrine) signals, loss of FAK solely in the endothelial cell compartment is able to induce chemosensitization to DNA-damaging therapies in the malignant cell compartment and thereby reduce tumor growth. Herein, we summarize the roles of EC-FAK in cancer and development and review the status of FAK-targeting anticancer strategies.

Background

Focal adhesion kinase signaling

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a member of the nonreceptor protein tyrosine kinase family, ubiquitously expressed, that signals downstream of integrins and growth factor receptors. Elevated levels of FAK have been associated with the progression of multiple malignant tumors, and its role in regulating cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis has been extensively studied (1–4). FAK consists of a central kinase domain, a C-terminal FAT domain, and an N-terminal FERM domain. Historically, the kinase activity of FAK was considered to be essential for its function. More recently, these data have been complicated by the fact that FAK also has scaffolding functions that are interrelated with the kinase activity.

Activation of integrins and growth factor receptors initiates disruption of an autoinhibitory intramolecular interaction between the FERM and kinase domains of FAK, allowing ATP binding to the kinase domain. This interaction induces phosphorylation at FAK-Y397 and enables SRC binding. Subsequent phosphorylation of additional tyrosine and serine motifs of FAK, including Y861 and Y925, results in full FAK activity (4, 5).

Downstream, FAK phosphorylation of the p85 subunit of PI3K triggers survival signals through the formation of PIP2/3 phospholipids and activation of AKT1. Moreover, FAK mediates motility by binding to, and phosphorylating, breast cancer antiestrogen resistance 1 (BCAR1) via a proline rich domain in the C-terminus of FAK. BCAR1 also mediates proliferation and survival by activation of MAPK8. FAK promotes focal adhesion turnover by suppressing RHO activity (6) and regulates proliferation and migration via binding growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (GRB2) at its phosphorylated Y925 site, which results in the activation of the GRB2/SOS/RAS/EPHB2 pathway. In addition, FAK can translocate into the nucleus to regulate transcriptional activity of TP53, MDM2, and RIP.

FAK in vivo mouse models

The creation of FAK-deficient mouse models has demonstrated the importance of FAK during development (7). Global deletion of Fak causes an early embryonic lethal phenotype with defects in the vascular system by E8.5 (8). Subsequent studies, using global Fak knock-in point mutations within the catalytic domain, further corroborated the role of FAK during development and revealed that FAK kinase activity is essential for blood vessel morphogenesis, cell motility, and polarity (9). Interestingly, studies using keratinocyte-specific Fak deletion showed an absolute requirement for FAK in malignant epidermal carcinoma formation, implicating FAK in tumorigenesis (10). Together, these data suggest that FAK is a regulator of tissue growth responses and malignant transformation.

Given that tumorigenesis can also be driven by signals between tumor cells and the microenvironment, the role of FAK in the microenvironment has also been assessed. FAK was recently described to promote antitumor immune evasion by increasing intratumoral regulatory T cells (11). Interestingly, studies performed with myeloid-specific Fak knockout (Fak KO) mice revealed the ability of FAK to decrease the pathogen-killing capacity of neutrophils (12). In contrast to previous reports, showing decreased metastasis after silencing Fak in tumor cells, or by FAK pharmacologic inhibition (13, 14), hematopoietic Fak deficiency in mice generates a prometastatic microenvironment that enhances tumor metastasis (15). These reports indicate a regulatory role for stromal FAK in cancer growth and spread.

Endothelial cell FAK in development and cancer

Given the predominant vascular defects observed in Fak-deficient mice, much work has focused on the role of FAK within the endothelial cell compartment using several models (16–23). Constitutive endothelial cell deletion of exon 3 of the Fak gene, using Tie2-Cre, caused lethality at E11.5 due to multiple vascular defects (reduced and disorganized blood vessel network, hemorrhage, and edema; ref. 20). Deletion of exon 2 in Tie2-Cre–positive cells resulted in reduced vessel growth and enhanced vessel regression (16). Several in vitro studies support the role of FAK in promoting cell proliferation (24, 25). Although reduced proliferation was observed upon deletion of endothelial cell FAK (EC-Fak) in exon 3 (20), no reduction in cell proliferation was reported when deleting EC-Fak exon 2 (16). Together, these data revealed FAK as an essential regulator of endothelial cell survival and vascular morphogenesis but indicate differential effects depending on the model used. The endothelial expression of kinase-defective (KD) Fak, although still embryonic lethal (E13.5), was able to rescue the increased apoptosis caused by deletion of Fak in endothelial cells through the regulation of p21, but also enhanced endothelial cell barrier function by increasing cadherin 5 (CDH5 or VE-cadherin) phosphorylation (23, 26). Changes in endothelial cell barrier function have also been shown to be controlled by EC-FAK and its autophosphorylation at Y397 in response to VEGF (17, 27).

To overcome the lethal consequences of constitutive EC-Fak deletion or mutation, studies turned to inducible systems to delete EC-Fak in adult mice (21, 22). Inducible loss of EC-Fak, driven by End-SCL (endothelial-small cell leukemic)-CreER in adult mice, had no effect on physiologic angiogenesis, probably caused by increased proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (PTK2B or PYK2) expression, another member of the nonreceptor protein kinase family (22). In contrast, EC-Fak loss driven by Pdgfb (platelet-derived growth factor b)-iCreER did not induce PYK2 upregulation and resulted in reduced tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth (21). Discrepancies between these two studies could be explained by the use of different promoters (Pdgfb vs. End-SCL), possibly targeting different endothelial cell subpopulations, leading to distinct spatial and temporal activities within the endothelium. Further studies using adult mice suggested that global FAK heterozygosity enhanced tumor-angiogenic responses by inducing endothelial activation (28). Additional investigations are required to elucidate the clinical relevance of these changing functions of EC-FAK in regulating tumor angiogenesis.

Furthermore, studies using the conditional endothelial cell–specific Fak-KO model revealed a role for FAK in the regulation of vascular permeability of the blood—brain barrier in glioma (29). Interestingly, inducible expression of KD FAK in endothelial cells was sufficient to inhibit tumor metastasis without impacting on primary tumor growth (18). Moreover, during the premetastatic phase, it has been reported that EC-FAK mediates focal lung vessel hyperpermeability, enhancing metastatic cancer cell homing by upregulating selectin E (SELE) in the lung vasculature (30).

Clinical–Translational Advances

FAK inhibitors

Given the upregulation of FAK in cancer, it is logical that several agents are being developed to target FAK for cancer therapy. FAK inhibitors have been designed to block ATP–kinase interactions directly or to target other FAK functions using alternative means. The latter approach includes allosteric FAK inhibitors (31, 32) and inhibitors that disrupt FAK scaffolding protein–protein interactions (33, 34). Although treatment with some of these compounds resulted in reduced tumor growth in colon xenograft models (34, 35), further studies regarding target selectivity are required. In particular, small molecule ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors have been shown to have an impact on several processes involved in tumor progression in preclinical experiments.

The small molecule inhibitor VS-4718 (previously PND-1186) has been reported to have high antitumor efficacy in breast carcinoma mouse models (36). VS-4718 also reduces tumor metastasis in ovarian carcinoma models (37) and human breast xenograft models (38) driven, in part, by its ability to modify the immunosuppressive tumor environment (11). Although the molecular mechanisms behind these phenotypes are not completely understood, VS-4718 has been described to decrease ovarian carcinoma αvβ5 integrin and secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) levels (37).

Interestingly, the dual FAK/PYK2 inhibitor VS-6062 (previously PF-562,271, Pfizer) is capable of inhibiting both FAK and PYK2 kinase activity while producing antitumor effects in multiple human subcutaneous xenograft models, (39) as well as decreasing tumor size and metastasis in several cancer types (14, 40–45). In addition, VS-6062 prevents the physical interaction between αvβ3 integrin and TGFβR-II and abrogates TGFβ-driven epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, invasion, and systemic dissemination of cancer cells (45). In contrast, studies performed with the prostate cancer TRAMP model showed that treatment with VS-6062 inhibits androgen-independent formation of neuroendocrine carcinoma but does not alter progression of prostate adenoma (46). Notably, treatment with VS-6062 affects also the tumor vasculature, leading to a decreased tumor-associated endothelial cell density (44), supporting previously published reports suggesting that FAK inhibition may have antiangiogenic effects (39). In addition, treatment with VS-6062 causes a blockade of VEGF-stimulated endothelial cell migration and inhibition of endothelial cell tube branching in vitro (42).

Further studies treating human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) with other FAK inhibitors, such as PF-573,228 inhibitor and FAK inhibitor 14, showed impaired endothelial cell migration and sprout formation in vitro and, in the case of PF-573,228, also induced endothelial cell apoptosis (47). Overall, these data suggest that FAK inhibitors likely have an antiangiogenic effect. However, it remains unknown whether the observed antiangiogenic effect of FAK inhibitors on tumors in vivo is due to their ability to directly inhibit tumor-associated angiogenesis (47), or secondary effects that reduce tumor burden, or both. Further research in this regard will give a better understanding of the effect of these compounds within the tumor and clarify the mechanism underlying these responses.

Some FAK kinase inhibitors have reached clinical trials: GSK2256098 (GlaxoSmithKline), VS-4718, VS-6062, VS-6063 (Verastem), and BI853520 [Boehringer Ingelheim (Table 1)]. VS-6062 was the first FAK inhibitor tested in clinical phase I trials but, despite promising results, it was discontinued due to nonlinear pharmacokinetics (48) and Verastem developed VS-6063. Trials using VS-6063 inhibitor are still ongoing and indicate promise in phase I dose-escalation studies, for example, in Japanese subjects with nonhematologic malignancies, no serious adverse effects were reported (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01943292). As MERLIN deficiency has been recently shown to predict FAK inhibitor sensitivity (49), a trial using VS-6063 (COMMAND) in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma investigated the effects of MER-LIN expression on drug efficacy. Unfortunately, this trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01870609) was terminated because effects were not justified in moving the study forward. Although VS-6063 will no longer be tested in patients with mesothelioma, many other trials are still recruiting participants.

Table 1.

Current status of clinical trials using FAK kinase inhibitors

| Drug name & specificity | Alternative names | Clinical trial identifiersa | Phase | Participants' condition | Therapies used in combination with FAK inhibitors | Current status | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSK2256098 | NCT01938443 | I | Advanced solid tumors | MEK inhibitor trametinib | Recruiting participants | Not available | |

| FAK | NCT01138033 | I | Solid tumors | N/A | Recruiting participants | ||

| NCT02551653 | I | Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension | N/A | Recruiting participants | |||

| NCT00996671 | I | Healthy | N/A | Completed | |||

| NCT02428270 | II | Advanced pancreatic cancer | MEK inhibitor trametinib | Not yet open for participant recruitment | |||

| NCT02523014 | II | Intracranial and recurrent meningioma | SMO antagonist vismodegib | Recruiting participants | |||

| VS-4718 | PND-1186 | NCT01849744 | I | Metastatic nonhematologic cancers | N/A | Recruiting participants | (18, 36–38, 49) |

| FAK/PYK2 | NCT02651727 | I | Pancreatic cancer | Chemotherapeutic drugs nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine | Recruiting participants | ||

| NCT02215629 | I | Acute myeloid or B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | N/A | Withdrawn prior to enrollment | |||

| VS-6062 FAK/PYK2 | PF-562,271, PF-271 | NCT00666926 | I | Head and neck, prostate, pancreatic neoplasms | N/A | Completed | (14, 17, 18, 39, 42, 48) |

| VS-6063 FAK/PYK2 | PF-04554878, defactinib | NCT02546531 | I | Advanced solid tumors and pancreatic cancer | Gemcitabine and the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab | Recruiting participants | (48, 50) |

| NCT02372227 | I | Relapsed malignant mesothelioma | PI3K/mTOR dual inhibitor VS-5584 | Ongoing; not recruiting participants | |||

| NCT01943292 | I | Nonhematologic cancers | N/A | Completed | |||

| NCT00787033 | I | Advanced nonhematologic cancers | N/A | Completed | |||

| NCT01778803 | I/Ib | Advanced ovarian cancer | Chemotherapeutic drug paclitaxel | Ongoing; not recruiting participants | |||

| NCT02004028 | II | Surgical resectable malignant pleural mesothelioma | N/A | Recruiting participants | |||

| NCT01951690 | II | Non–small cell lung cancer | N/A | Ongoing; not recruiting participants | |||

| NCT01870609 | II | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | N/A | Terminated | |||

| NCT02465060b | II | Advanced malignant neoplasm, lymphoma, refractory malignant neoplasm, and solid neoplasm | N/A | Suspended participant recruitment | |||

| BI853520 | NCT01905111 | I | Advanced or metastatic cancer | N/A | Completed | N/A | |

| FAK/PYK2 | NCT01335269 | I | Advanced or metastatic cancer | N/A | Completed | ||

EC-FAK, chemosensitivity, and angiocrine signaling

Increasing evidence favors combining FAK inhibitors with chemotherapy for overcoming side effects and chemotherapeutic resistance. It has been described that inhibition of FAK enhances chemosensitivity in taxane-resistant cells (50), and combination of FAK inhibitors and docetaxel results in tumor regression in ovarian cancer (51). Interestingly, in rat xenograft models, sunitinib combined with FAK inhibitor not only blocked tumor growth but also had an impact on the ability of the tumor to recover upon withdrawal of the therapy (52). FAK activation has also been associated with increased insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP2) expression, thus partially contributing to IGFBP2-mediated dasatinib resistance in non–small cell lung cancer (53), supporting the notion that FAK inhibition can positively influence the chemotherapeutic response of the tumor. However, not all therapeutic combinations can always have the best outcomes. For example, it has been described that combination of FAK inhibitors with radiotherapy promotes radioresistance in mouse squamous cell carcinoma cells (54), and combination of gemcitabine with FAK inhibitor shows no improvement in tumor growth reduction in comparison with monotherapies alone (14). In contrast, recent studies showed that combination of FAK and BRAF inhibitors significantly reduced burden when compared with either treatment alone (55). The results of these studies indicate that the added benefit of FAK inhibition in combination therapy may be dependent on the chemotherapeutic used. Although the molecular mechanisms underlying these data are presently unknown, future studies may provide further insight into improved combination approaches.

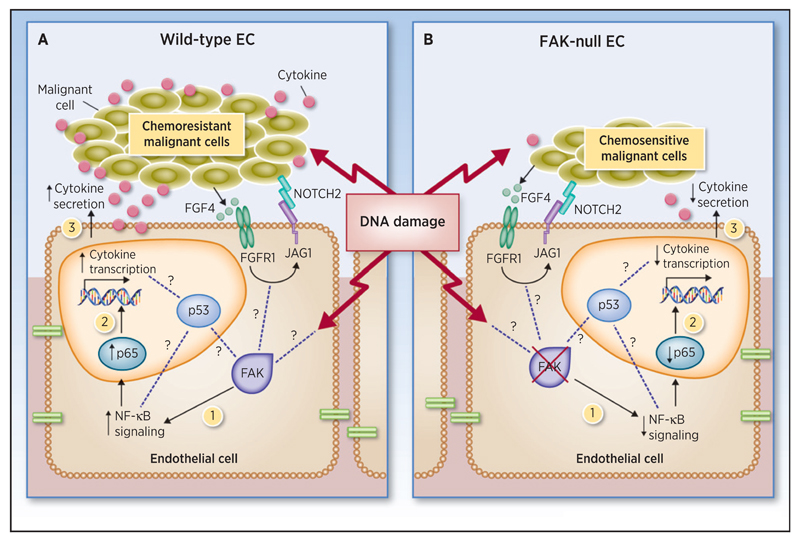

Endothelial-specific genetic ablation approaches, rather than systemic inhibitors, have directly linked endothelial cells in chemosensitization. Interestingly, paracrine factors generated by endothelial cells (namely angiocrine factors) have been described to modulate malignant cell responses and induce chemoresistance. For example, endothelial-derived IL6 has been implicated as a regulator of chemoresistance in lymphoma (56), and the upregulation of the Notch–Jagged pathway in endothelial cells has been demonstrated to control chemoresistance (Fig. 1; ref. 57). In this study, Jagged1 (JAG1) has been shown to regulate angiocrine signaling and chemoresistance via the activation of FGFR1 in B-cell lymphoma (57). In line with this observation, EC-FAK has been recently identified to play a decisive role in creating an angiocrine-derived chemoprotective niche (58). Interestingly, genetic ablation of EC-Fak in established syngeneic B16F0 or CMT19T tumors using the endothelial cell–specific deletor mouse model Pdgfb-iCreER; Fakfl/fl, is not sufficient to affect tumor angiogenesis or tumor growth per se. However, treating these tumorbearing EC-Fak-KO mice with DNA-damaging therapies, such as doxorubicin or radiation, is sufficient to sensitize malignant cells to these therapies, resulting in significantly reduced tumor growth (more than a 4-fold reduction) without affecting drug delivery (58). In addition, EC-Fak deletion significantly extends median survival of doxorubicin-treated mice in experimental metastasis models of melanoma and lymphoma (58). Perivascular tumor cell niches of EC-Fak-KO treated mice display reduced tumor cell proliferation and enhanced apoptosis. Mechanistically, DNA damage in EC-Fak-KO mice reduces endothelial cell–NF-κB activity, which drives decreased p65 subunit translocation into the nucleus and reduced endothelial cell–derived cytokine production, thus inhibiting the angiocrine signal that protects malignant cells from DNA damage in vivo (Fig. 1; ref. 58). This novel function of EC-FAK as a regulator of chemosensitivity opens new perspectives for future research avenues and new possible strategies for future applications in the clinic. The molecular mechanism by which DNA damage affects FAK in endothelial cells is unknown. In addition, how EC-FAK controls other players in angiocrine signaling, such as Jagged signaling, is yet to be explored. Several lines of data indicate not only that TP53 can bind FAK but also that it can regulate NF-κB signaling and cytokine production (59–61). Thus, examining how endothelial cell–TP53 and EC-FAK might work together to control NF-κB signaling and cytokine production after DNA damage in the control of malignant cell chemosensitization will be of great interest. To date, the role of EC-FAK in chemosensitization has only been described with DNA-damaging therapies and in tumors derived from murine lung, lymphoma, and melanoma cell lines (58). Whether this mechanism of control of chemosensitivity is relevant to FAK inhibitors and other tumor types with other chemotherapeutics is still unknown and will require additional work.

Figure 1.

Loss of EC-FAK induces chemosensitivity in malignant cells via the regulation of angiocrine factors. A, wild-type endothelial cells (EC). Upon DNA damage, EC-FAK induces (1) activation of the NF-κB pathway causing (2) increased translocation of the NF-κB subunit p65 into the nucleus and (3) elevated cytokine transcription and secretion. This increase in cytokine secretion by tumor-associated endothelial cells creates a chemoresistant niche protecting tumor cells from DNA damage. B, FAK-null ECs: In contrast, upon DNA damage in EC-Fak–null mice with established tumors, (1) NF-κB activity is reduced (2) inhibiting p65 translocation into the nucleus, thus (3) decreasing cytokine transcription and secretion. Thus, loss of EC-Fak reduces the angiocrine signal that protects malignant cells from DNA damage. How other pathways, including NOTCH–JAG1 or TP53, affect angiocrine signaling controlled by FAK is currently unknown.

Summary and Future Perspectives

Given the ubiquitous expression of FAK in both malignant and stromal cells, the inhibition of FAK for cancer control is attractive. Given that genetic ablation of EC-Fak in established tumors is also sufficient to chemosensitize tumor cells and improve tumor growth control, several questions arise, including the following: Could EC-FAK be an effective anticancer target? Future research will be required to address this question and to determine whether or not this will be an important advance. Meanwhile, targeting FAK will continue to be an important area of investigation with the ultimate goal of eradicating tumor progression growth and dissemination.

Acknowledgments

The authors apologize to colleagues whose work they were unable to cite due to space constraints.

Grant Support

M. Roy-Luzarraga is supported by a Cancer Research UK studentship (grant number, C8218/A21453). K. Hodivala-Dilke is supported by Cancer Research UK (grant number, C8218/A18673).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Authors' Contributions

Conception and design: M. Roy-Luzarraga, K. Hodivala-Dilke

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: M. Roy-Luzarraga, K. Hodivala-Dilke

Study supervision: K. Hodivala-Dilke

Other (figure creation): M. Roy-Luzarraga

References

- 1.Gabarra-Niecko V, Schaller MD, Dunty JM. FAK regulates biological processes important for the pathogenesis of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:359–74. doi: 10.1023/a:1023725029589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer - a new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:505–15. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sulzmaier FJ, Jean C, Schlaepfer DD. FAK in cancer: mechanistic findings and clinical applications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:598–610. doi: 10.1038/nrc3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Nimwegen MJ, van de Water B. Focal adhesion kinase: a potential target in cancer therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lechertier T, Hodivala-Dilke K. Focal adhesion kinase and tumour angiogenesis. J Pathol. 2012;226:404–12. doi: 10.1002/path.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren XD, Kiosses WB, Sieg DJ, Otey CA, Schlaepfer DD, Schwartz MA. Focal adhesion kinase suppresses Rho activity to promote focal adhesion turnover. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3673–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.20.3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, et al. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:539–44. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilic D, Kovacic B, McDonagh S, Jin F, Baumbusch C, Gardner DG, et al. Focal adhesion kinase is required for blood vessel morphogenesis. Circ Res. 2003;92:300–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000055016.36679.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim ST, Chen XL, Tomar A, Miller NL, Yoo J, Schlaepfer DD. Knock-in mutation reveals an essential role for focal adhesion kinase activity in blood vessel morphogenesis and cell motility-polarity but not cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21526–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLean GW, Komiyama NH, Serrels B, Asano H, Reynolds L, Conti F, et al. Specific deletion of focal adhesion kinase suppresses tumor formation and blocks malignant progression. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2998–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.316304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrels A, Lund T, Serrels B, Byron A, McPherson RC, von Kriegsheim A, et al. Nuclear FAK controls chemokine transcription, Tregs, and evasion of antitumor immunity. Cell. 2015;163:160–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasorn A, Alcaide P, Jia Y, Subramanian KK, Sarraj B, Li Y, et al. Focal adhesion kinase regulates pathogen-killing capability and life span of neutrophils via mediating both adhesion-dependent and -independent cellular signals. J Immunol. 2009;183:1032–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitra SK, Lim ST, Chi A, Schlaepfer DD. Intrinsic focal adhesion kinase activity controls orthotopic breast carcinoma metastasis via the regulation of urokinase plasminogen activator expression in a syngeneic tumor model. Oncogene. 2006;25:4429–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stokes JB, Adair SJ, Slack-Davis JK, Walters DM, Tilghman RW, Hershey ED, et al. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase by PF-562,271 inhibits the growth and metastasis of pancreatic cancer concomitant with altering the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2135–45. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batista S, Maniati E, Reynolds LE, Tavora B, Lees DM, Fernandez I, et al. Haematopoietic focal adhesion kinase deficiency alters haematopoietic homeostasis to drive tumour metastasis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5054. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braren R, Hu H, Kim YH, Beggs HE, Reichardt LF, Wang R. Endothelial FAK is essential for vascular network stability, cell survival, and lamellipodial formation. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:151–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen XL, Nam JO, Jean C, Lawson C, Walsh CT, Goka E, et al. VEGF-induced vascular permeability is mediated by FAK. Dev Cell. 2012;22:146–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jean C, Chen XL, Nam JO, Tancioni I, Uryu S, Lawson C, et al. Inhibition of endothelial FAK activity prevents tumor metastasis by enhancing barrier function. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:247–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt TT, Tauseef M, Yue L, Bonini MG, Gothert J, Shen TL, et al. Conditional deletion of FAK in mice endothelium disrupts lung vascular barrier function due to destabilization of RhoA and Rac1 activities. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305:L291–300. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00094.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen TL, Park AY, Alcaraz A, Peng X, Jang I, Koni P, et al. Conditional knockout of focal adhesion kinase in endothelial cells reveals its role in angiogenesis and vascular development in late embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:941–52. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavora B, Batista S, Reynolds LE, Jadeja S, Robinson S, Kostourou V, et al. Endothelial FAK is required for tumour angiogenesis. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:516–28. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weis SM, Lim ST, Lutu-Fuga KM, Barnes LA, Chen XL, Gothert JR, et al. Compensatory role for Pyk2 during angiogenesis in adult mice lacking endothelial cell FAK. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:43–50. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao X, Peng X, Sun S, Park AY, Guan JL. Role of kinase-independent and -dependent functions of FAK in endothelial cell survival and barrier function during embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:955–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilmore AP, Romer LH. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling in focal adhesions decreases cell motility and proliferation. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1209–24. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao JH, Reiske H, Guan JL. Regulation of the cell cycle by focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1997–2008. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arnold KM, Goeckeler ZM, Wysolmerski RB. Loss of focal adhesion kinase enhances endothelial barrier function and increases focal adhesions. Microcirculation. 2013;20:637–49. doi: 10.1111/micc.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corsi JM, Houbron C, Billuart P, Brunet I, Bouvree K, Eichmann A, et al. Autophosphorylation-independent and -dependent functions of focal adhesion kinase during development. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34769–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.067280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostourou V, Lechertier T, Reynolds LE, Lees DM, Baker M, Jones DT, et al. FAK-heterozygous mice display enhanced tumour angiogenesis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2020. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Borboa AK, Chun HB, Baird A, Eliceiri BP. Conditional deletion of the focal adhesion kinase FAK alters remodeling of the blood-brain barrier in glioma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:10131–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hiratsuka S, Goel S, Kamoun WS, Maru Y, Fukumura D, Duda DG, et al. Endothelial focal adhesion kinase mediates cancer cell homing to discrete regions of the lungs via E-selectin up-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3725–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100446108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heinrich T, Seenisamy J, Emmanuvel L, Kulkarni SS, Bomke J, Rohdich F, et al. Fragment-based discovery of new highly substituted 1H-pyrrolo[2,3-b]- and 3H-imidazolo[4,5-b]-pyridines as focal adhesion kinase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2013;56:1160–70. doi: 10.1021/jm3016014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomita N, Hayashi Y, Suzuki S, Oomori Y, Aramaki Y, Matsushita Y, et al. Structure-based discovery of cellular-active allosteric inhibitors of FAK. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:1779–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cance WG, Kurenova E, Marlowe T, Golubovskaya V. Disrupting the scaffold to improve focal adhesion kinase-targeted cancer therapeutics. Sci Signal. 2013;6:pe10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Golubovskaya VM, Ho B, Zheng M, Magis A, Ostrov D, Morrison C, et al. Disruption of focal adhesion kinase and p53 interaction with small molecule compound R2 reactivated p53 and blocked tumor growth. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:342. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golubovskaya VM, Figel S, Ho BT, Johnson CP, Yemma M, Huang G, et al. A small molecule focal adhesion kinase (FAK) inhibitor, targeting Y397 site: 1-(2-hydroxyethyl)-3, 5, 7-triaza-1-azoniatricyclo [3.3.1.1(3,7)]decane; bromide effectively inhibits FAK autophosphorylation activity and decreases cancer cell viability, clonogenicity and tumor growth in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1004–13. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanjoni I, Walsh C, Uryu S, Tomar A, Nam JO, Mielgo A, et al. PND-1186 FAK inhibitor selectively promotes tumor cell apoptosis in three-dimensional environments. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:764–77. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.10.11434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tancioni I, Uryu S, Sulzmaier FJ, Shah NR, Lawson C, Miller NL, et al. FAK Inhibition disrupts a beta5 integrin signaling axis controlling anchorage-independent ovarian carcinoma growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13:2050–61. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walsh C, Tanjoni I, Uryu S, Tomar A, Nam JO, Luo H, et al. Oral delivery of PND-1186 FAK inhibitor decreases tumor growth and spontaneous breast to lung metastasis in pre-clinical models. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:778–90. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.10.11433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts WG, Ung E, Whalen P, Cooper B, Hulford C, Autry C, et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacology of a selective focal adhesion kinase inhibitor, PF-562,271. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1935–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bagi CM, Roberts GW, Andresen CJ. Dual focal adhesion kinase/Pyk2 inhibitor has positive effects on bone tumors: implications for bone metastases. Cancer. 2008;112:2313–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Serrels A, McLeod K, Canel M, Kinnaird A, Graham K, Frame MC, et al. The role of focal adhesion kinase catalytic activity on the proliferation and migration of squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2012;131:287–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stone RL, Baggerly KA, Armaiz-Pena GN, Kang Y, Sanguino AM, Thanapprapasr D, et al. Focal adhesion kinase: an alternative focus for antiangiogenesis therapy in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:919–29. doi: 10.4161/cbt.28882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sun H, Pisle S, Gardner ER, Figg WD. Bioluminescent imaging study: FAK inhibitor, PF-562,271, preclinical study in PC3M-luc-C6 local implant and metastasis xenograft models. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:38–43. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.1.11993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ward KK, Tancioni I, Lawson C, Miller NL, Jean C, Chen XL, et al. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) activity prevents anchorage-independent ovarian carcinoma cell growth and tumor progression. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:579–94. doi: 10.1007/s10585-012-9562-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wendt MK, Schiemann WP. Therapeutic targeting of the focal adhesion complex prevents oncogenic TGF-beta signaling and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slack-Davis JK, Hershey ED, Theodorescu D, Frierson HF, Parsons JT. Differential requirement for focal adhesion kinase signaling in cancer progression in the transgenic adenocarcinoma of mouse prostate model. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:2470–7. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cabrita MA, Jones LM, Quizi JL, Sabourin LA, McKay BC, Addison CL. Focal adhesion kinase inhibitors are potent anti-angiogenic agents. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:517–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Infante JR, Camidge DR, Mileshkin LR, Chen EX, Hicks RJ, Rischin D, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic phase I dose-escalation trial of PF-00562271, an inhibitor of focal adhesion kinase, in advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1527–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shapiro IM, Kolev VN, Vidal CM, Kadariya Y, Ring JE, Wright Q, et al. Merlin deficiency predicts FAK inhibitor sensitivity: a synthetic lethal relationship. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:237ra68. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kang Y, Hu W, Ivan C, Dalton HJ, Miyake T, Pecot CV, et al. Role of focal adhesion kinase in regulating YB-1-mediated paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1485–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halder J, Lin YG, Merritt WM, Spannuth WA, Nick AM, Honda T, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of a novel focal adhesion kinase inhibitor TAE226 in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10976–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bagi CM, Christensen J, Cohen DP, Roberts WG, Wilkie D, Swanson T, et al. Sunitinib and PF-562,271 (FAK/Pyk2 inhibitor) effectively block growth and recovery of human hepatocellular carcinoma in a rat xenograft model. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:856–65. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.9.8246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu H, Wang L, Gao W, Meng J, Dai B, Wu S, et al. IGFBP2/FAK pathway is causally associated with dasatinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:2864–73. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Graham K, Moran-Jones K, Sansom OJ, Brunton VG, Frame MC. FAK deletion promotes p53-mediated induction of p21, DNA-damage responses and radio-resistance in advanced squamous cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirata E, Girotti MR, Viros A, Hooper S, Spencer-Dene B, Matsuda M, et al. Intravital imaging reveals how BRAF inhibition generates drug-tolerant microenvironments with high integrin beta1/FAK signaling. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:574–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gilbert LA, Hemann MT. DNA damage-mediated induction of a chemoresistant niche. Cell. 2010;143:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao Z, Ding BS, Guo P, Lee SB, Butler JM, Casey SC, et al. Angiocrine factors deployed by tumor vascular niche induce B cell lymphoma invasiveness and chemoresistance. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:350–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tavora B, Reynolds LE, Batista S, Demircioglu F, Fernandez I, Lechertier T, et al. Endothelial-cell FAK targeting sensitizes tumours to DNA-damaging therapy. Nature. 2014;514:112–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ilic D, Almeida EA, Schlaepfer DD, Dazin P, Aizawa S, Damsky CH. Extracellular matrix survival signals transduced by focal adhesion kinase suppress p53-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:547–60. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim ST, Chen XL, Lim Y, Hanson DA, Vo TT, Howerton K, et al. Nuclear FAK promotes cell proliferation and survival through FERM-enhanced p53 degradation. Mol Cell. 2008;29:9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim ST, Miller NL, Nam JO, Chen XL, Lim Y, Schlaepfer DD. Pyk2 inhibition of p53 as an adaptive and intrinsic mechanism facilitating cell proliferation and survival. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:1743–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]