Abstract

Although most patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy have a favorable outcome, complications are not uncommon. Recent studies have reported an increase in incidence of cardioembolic complications; however, the association between takotsubo cardiomyopathy and stroke, in particular thromboembolic cerebral infarction, remains unclear. We reported a 44-year-old woman who had a cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy. She had felt chest discomfort a few days prior to infarction, and later developed left hemiparesis. Head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed acute infarction in the right insular cortex and occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery at the M2 segment. Echocardiogram revealed a takotsubo-like shape in the motion of the left ventricular wall, and coronary angiography showed neither coronary stenosis nor occlusion. Cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy was diagnosed and treatment with anticoagulant was started. MRI on the eighth day after hospitalization showed recanalization of the right middle cerebral artery and no new ischemic lesions. The findings of the 19 previously published cases who had cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy were also reviewed and showed the median interval between takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cerebral infarction was approximately 1 week and cardiac thrombus was detected in 9 of 19 patients. We revealed that thromboembolic events occurred later than other complications of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and longer observation might be required due to possible cardiogenic cerebral infarction. Anticoagulant therapy is recommended for patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy with cardiac thrombus or a large area of akinetic left ventricle.

Keywords: takotsubo cardiomyopathy, stroke, thromboembolic cerebral infarction, cardiogenic cerebral infarction

Introduction

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a non-ischemic type of heart disease, and its symptoms and electrocardiogram (ECG) changes mimic acute myocardial infarction, characterized by a sudden onset of chest pain and ECG abnormality, with ST elevation or T-wave inversion. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is diagnosed if left ventricular akinesis or dyskinesis in the absence of significant coronary artery occlusion is observed. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy accounts for approximately 1–3% of patients presenting with symptoms that appear to be an acute coronary syndrome. Although prognosis is generally good, complications including cardiogenic shock or arrhythmia occur in 20–50% of patients, and mortality in 2% of patients.1–3)

Recently, reports of thromboembolic complications in patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy have been increasing, and the most common type of thromboembolic complications is cerebral infarction.4) However, neither the timing of thromboembolism resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy nor the treatment have been well described. Here, we report a case of cerebral infarction arising from takotsubo cardiomyopathy and review the available literature.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman was transferred to the emergency department of our hospital with left hemiparesis and dysarthria within 1 hour from stroke onset. A few days prior to this, she had felt chest discomfort without etiology, and her chest pain had increased the 4 hours prior to stroke onset. She had no prodrome including illness. In the past, she had been admitted to the department of cardiology in our hospital for acute heart failure with hypertension; when her heart function was improved, echocardiogram had shown no evidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. She had been prescribed a calcium blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor by her family doctor and showed no symptoms before stroke onset. She had no other past medical history, but she was smoker.

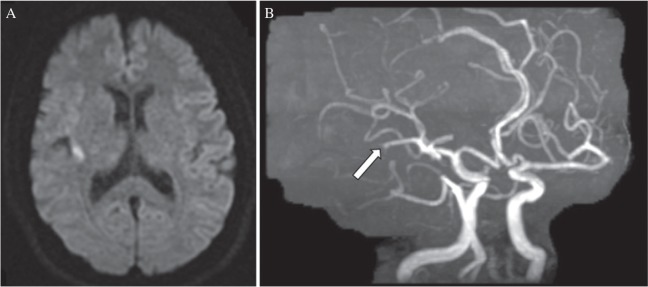

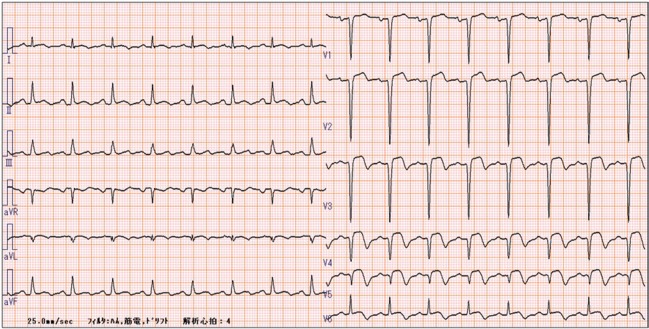

Her neurological symptoms steadily improved on the way to the hospital, and her National Institutes Health Stroke Scale score was 2 at arrival and 0 after magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Head MRI showed acute infarction in the right insular cortex and occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery at the M2 segment (Fig. 1A and B). ECG showed ST elevations in leads V2-5 and inverted T-waves in V2-6 (Fig. 2). Laboratory analysis revealed CPK was 773 U/l (normal, 30–170 U/l), CK-MB was 86 IU/l (normal, 0–25 IU/l), BNP was 117 pg/ml (normal, 0–18.4 pg/ml) and levels of troponin-T and fatty acid binding protein were elevated. Echocardiography showed the left ventricular wall motion had a takotsubo-like shape: akinesis of the mid and distal segments of the left ventricle and hyperkinesis of the basal segments. Thrombus formation was not detected.

Fig. 1.

MRI and MRA findings on admission. DWI shows high signal intensity in the right insula cortex (A) and MRA shows occlusion of the mid portion of the right inferior M2 trunk (B, arrow).

Fig. 2.

ECG shows ST elevations in leads V2-5 and inverted T-waves in V2-6.

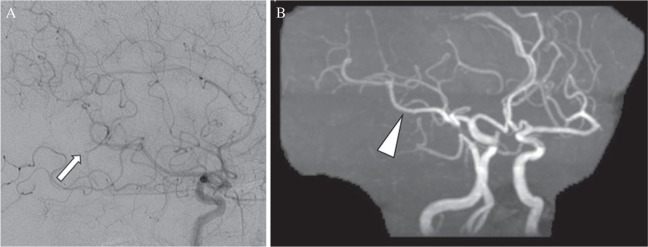

Coronary angiography was immediately performed and no coronary stenosis or occlusion was detected. Cerebral angiography was simultaneously performed and the right carotid angiography showed a thrombus migrated from the M2 to M3 segment (Fig. 3A). Because her neurological deficits disappeared, endovascular therapy was not performed. Left ventricular angiography was not attempted to avoid excessive administration of contrast medium. She was admitted to the intensive care unit and unfractionated heparin and warfarin therapy was started. MRI on the eighth day after hospitalization showed recanalization of the right middle cerebral artery and no new ischemic lesions (Fig. 3B). Holter electrocardiography and carotid echocardiography were unable to elucidate the source of the thromboembolism. Taking into account her clinical presentation and laboratory results, a final diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy causing cerebral infarction was made. She was discharged on the ninth day, and echocardiogram on the twenty-sixth day showed partial improvement in wall motion. Anticoagulant therapy is planned to be continued until the full improvement of the patient’s heart wall motion. Until now, we continue anticoagulant therapy for 7 months and she has no episode of cerebral infarction.

Fig. 3.

Right carotid angiography shows the thrombus migrated from the M2 to M3 segment (A, arrow). Repeated MRI on the eighth day of hospitalization shows recanalization of the right middle cerebral artery (B, arrowhead) and no new ischemic lesion.

Discussion

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was first described in 1990 in Japan, so-named due to the shape of the left ventricle appearing like a takotsubo (Japanese octopus trap); however, in other countries, takotsubo cardiomyopathy is also known as apical ballooning syndrome, ampulla cardiomyopathy, stress cardiomyopathy, and broken heart disease. Although the most common trigger is known to be emotional stress,2) intracranial disease, in particular subarachnoid hemorrhage, is also known to cause takotsubo cardiomyopathy. However, the Mayo Criteria requires the absence of recent significant head trauma and intracranial bleeding for the diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy,5) and the guidelines for diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in Japan suggest that takotsubo cardiomyopathy with cerebrovascular disease should instead be named cerebrovascular disease with takotsubo-like myocardial dysfunction.6) In addition, cerebral infarction7) or seizure8) are also known to cause takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Yoshimura et al. investigated 569 patients with acute ischemic stroke and found takotsubo cardiomyopathy in seven patients (1.2%).7) All patients were female and aged 75 years or older. In all cases, cerebral infarction proceeded takotsubo cardiomyopathy.

Frequent complications in takotsubo cardiomyopathy are arrhythmia or acute heart failure, similar to acute coronary syndrome. Thromboembolic complications occur occasionally, with cardiac thrombus formed in 3.7–8% of takotsubo cardiomyopathy patients;9,10) in particular, patients with negative T-waves in ECG tend to have cardiac thrombus.3)

The chronological sequence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cerebral infarction can be divided into three patterns: (A) cerebral infarction causing takotsubo cardiomyopathy, (B) left ventricular thrombus in takotsubo cardiomyopathy causing cerebral infarction, (C) cerebral infarction and takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurring simultaneously, including cases in which it is unknown which preceded the other.11,12) In cases whose cerebral infarction and takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurred simultaneously or who had both cerebral infarction and takotsubo cardiomyopathy on admission, it was difficult to judge which preceded the other. However, in cases of Group C, in which chronological relationship between stroke and takotsubo cardiomyopathy was unclear, reported by Kato et al.,12) no patients felt cardiac symptom before stroke onset. They also reported that most of patients suffering from cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy felt chest discomfort prior to stroke onset. In our case, the patient felt chest discomfort prior to stroke onset and had no sources of thromboembolism. Then, we concluded that takotsubo cardiomyopathy caused cerebral infarction in our patient. The incidence of cerebral infarction due to takotsubo cardiomyopathy ranges from 0 to 9.5%.13,14) In Okayama City Hospital, patients who were diagnosed with takotsubo cardiomyopathy from January 2004 to December 2014 were 27 patients and cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy was found in one case (3.7%).

To the best of our knowledge, twenty-three cases of cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy have been reported, and we reviewed the 19 cases that were described in detail written in English (Table 1).15–26) The mean age was 73.1 ± 11.5 years, and most cases (94.7%) were women. The trigger events of takotsubo cardiomyopathy were shown in 11 cases; six were physical stress, five were emotional stress. Although neurosurgeons typically experience cerebrovascular disease with takotsubo-like myocardial dysfunction complicated with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), there are no reports of thromboembolic cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo-like myocardial dysfunction after SAH. Severe ventricular dysfunction after SAH was known to an independent predictor of stroke from vasospasm and Lee at al. reported six patients (75%) showed cerebral vasospasm and three patients (37.5%) developed cerebral infarction in eight with SAH-induced takotsubo cardiomyopathy.27) We suppose that cerebral vasospasm-induced thromboembolic cerebral infarction may mask takotsubo cardiomyopathy-induced cerebral infarction in patients with SAH. The interval between takotsubo cardiomyopathy symptom onset and cerebral infarction was described in only 11 cases; nine cases (81.8%) were within one week, five of which (45.5%) were within three days. On the other hand, two cases reported cerebral infarction after more than a week (10 and 13 days). Although most complications associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy occurred within 3 days,3) the mean interval between takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cerebral infarction was approximately 1 week (4.8 ± 3.7 days). Interestingly, Matsuzono et al. reported a case in which cerebral infarction occurred 5 days after the diagnosis of takotsubo cardiomyopathy, and on that day echocardiography had shown improvement of wall motion. This suggests that longer observation may be required for thromboembolic events even after amelioration of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Cardiac thrombus was detected in 47.4% of the 19 cases, and more than half of the cases experienced cerebral infarction without cardiac thrombus. Samardhi et al. suggested patients with definite thrombus or those with large akinetic segments of the left ventricle should be considered for anticoagulant therapy until recovery of ventricular function. As mentioned above, the frequency of cerebral infarction due to takotsubo cardiomyopathy ranges from 0 to 9.5% and it is same or higher than the frequency of stroke after atrial fibrillation (4–9%)28) or myocardial infarction (4.6%)29) and other researchers also suggested anticoagulant therapy in takostubo cardiomyopathy.30,31) Our results also support this. After cerebral infarction, most patients were treated with anti-coagulant, however, the optimal duration of anticoagulant therapy after stroke onset remains under debate. Yonekawa et al. reported that they discontinued nadroparin after resolution of thrombus and full recovery of left ventricular function, but other reports did not describe the duration of treatment. Elesber et al. reported that the recurrence incidence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy was high within the first 4 years, at about 2.9% per year, and then decreased to about 1.3% per year. In the present study, we will continue anticoagulant therapy until the patient’s abnormal heart wall motion is fully resolved.

Table 1.

Literature review of cerebral infarction resulting from takotsubo cardiomyopathy

| Authors, year | Age /Sex | Trigger event | Tc symptoms | Stroke symptoms | Tc to stroke | Thrombus (Resolved) | Treatment prior to stroke | Treatment post stroke |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matsuoka et al., 2004 | 57, F | NA | None | Palsy of rt. arm | 2 days | Present (4 weeks later) | None | AC |

| Grabowski et al., 2007 | 85, F | NA | None | Palsy of rt. arm | NA | Absent | None | NA |

| 64, F | NA | None | Motor aphasia | NA | Present | None | AC | |

| De Gregorio et al., 2008 | 74, F | Physical stress | Dyspnea, fatigue | Dysphasia, palsy of right arm | NA | Present (2 weeks later) | None | AC |

| Mitsuma et al., 2008 | 83, F | None | Chest pain | Consciousness disorder, hemiparesis | > 48 hours | Absent | NA | AC |

| 81, F | Emotional stress | Chest discomfort | Dysphemia, hemiparesis | > 48 hours | Absent | NA | AC | |

| Schmidt et al., 2009 | 70, F | NA | Dyspnea, chest discomfort | Sensory aphasia | 3 days | Present (3 months later) | AC | AC |

| Jabiri et al., 2010 | 55, F | Emotional stress | Chest pain | Lt. hemiparesis | 4 days | Absent | None | rt-PA |

| Shin et al., 2011 | 76, F | NA | Nausea, abdominal discomfort | Consciousness disorder | 10 days | Present (1 week later) | None | AC |

| Yonekawa et al., 2011 | 61, F | Physical stress | NA | Palsy of lt. hand | 7 days | Present | None | AC |

| Kurisu et al., 2011 | 82, F | NA | None | Consciousness disorder | NA | Present | AC | NA |

| Lee et al., 2011 | 43, F | Emotional stress | Chest pain diaphoresis | Nausea, vomiting | The same day | Absent | None | AC |

| Yaylali et al., 2012 | 81, F | Physical stress | Nausea | Lt. Hemiparesis | NA | Absent | AC* | AP |

| Kim et al., 2012 | NA | Emotional stress | NA | NA | NA | Present | NA | AC |

| Matsuzono et al., 2013 | 71, F | Physical stress | None | Rt. Hemiparesis | 5 days | Present | AC | AC |

| Young et al., 2014 | 68, F | Physical stress | NA | Consciousness disorder | 5 days | Absent | None | NA |

| 80, F | None | Dyspnea | NA | 13 days | Absent | None | NA | |

| 85, F | Physical stress | Chest pain | NA | 2 days | Absent | AC** | NA | |

| 84, F | Emotional stress | Chest pain | NA | 2 days | Absent | AP*** | NA |

AC: Anticoagulant therapy, AP: Antiplatelet therapy, TC: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy,

Discontinued before stroke onset because of side effects,

Had a history of atrial fibrillation and took anticoagulant therapy prior to admission,

Had a history of stroke and took aspirin prior to admission.

Conclusion

Although the incidence of cerebral infarction was lower than other complications, longer observation may be required due to possible cardiogenic cerebral infarction. Additionally, we recommend anticoagulant therapy for patients with cardiac thrombus or a large area of akinetic left ventricle.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Disclosure

None of the authors have any disclosure to report.

References

- 1). Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, Wright RS, Lerman A, Rihal CS: Four-year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 50: 448– 452, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Samardhi H, Raffel OC, Savage M, Sirisena T, Bett N, Pincus M, Small A, Walters DL: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: An Australian single centre experience with medium term follow up. Intern Med J 42: 35– 42, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Schwab J, Pistner W, Gottwald U, Schoeller R, Toepel W, Winter KD, Stellbrink C, Müller-Honold T, Wegner C, Sechtem U: Complications in the clinical course of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 176: 199– 205, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). De Gregorio C: Cardioembolic outcomes in stress-related cardiomyopathy complicated by ventricular thrombus: A systematic review of 26 clinical studies. Int J Cardiol 141: 11– 17, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, Lerman A, Barsness GW, Wright RS, Rihal CS: Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med 141: 858– 865, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Kawai S, Kitabatake A, Tomoike H: Guidelines for diagnosis of takotsubo (ampulla) cardiomyopathy. Circ J 71: 990– 992, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Yoshimura S, Toyoda K, Ohara T, Nagasawa H, Ohtani N, Kuwashiro T, Naritomi H, Minematsu K: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in acute ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol 64: 547– 554, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Wakabayashi K, Dohi T, Daida H: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with epilepsy complicated with giant thrombus. Int J Cardiol 148: e28– e30, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Haghi D, Papavassiliu T, Heggemann F, Kaden JJ, Borggrefe M, Suselbeck T: Incidence and clinical significance of left ventricular thrombus in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy assessed with echocardiography. QJM 101: 381– 386, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, Maron MS, Hauser RG, Lesser JN, Haas TS, Hodges JS, Maron BJ: Natural History and Expansive Clinical Profile of Stress (Tako-Tsubo) Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 55: 333– 341, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Akyüz AR, Korkmaz L, Turan T, Varlıbaş A: Which is first? Whether Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was complicated with acute stroke or acute stroke caused Takotsubo cardiomyopathy? A case report. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 14: 648– 649, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Kato Y, Takeda H, Furuya D, Deguchi I, Tanahashi N: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and cerebral infarction. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 47: 601– 604, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Young ML, Stoehr J, Aguilar MI, Fortuin FD: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and stroke. Int J Cardiol 176: 574– 576, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Mitsuma W, Kodama M, Ito M, Kimura S, Tanaka K, Hoyano M, Hirono S, Aizawa Y: Thromboembolism in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 139: 98– 100, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Matsuoka K, Nakayama S, Okubo S, Fujii E, Uchida F, Nakano T: Transient cerebral ischemic attack induced by transient left ventricular apical balliining. Eur J Intern Med 15: 393– 395, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Grabowski A, Kilian J, Strank C, Cieslinski G, Meyding-Lamadé U: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy - A rare cause of cardioembolic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 24: 146– 148, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). De Gregorio C, Cento D, Di Bella G, Coglitore S: Minor stroke in a Takotsubo-like syndrome: A rare clinical presentation due to transient left ventricular thrombus. Int J Cardiol 130: e78– e80, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Schmidt M, Herholz C, Block M: Apical thrombus in tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2009: bcr2006100941, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Jabiri MZ, Mazighi M, Meimoun P, Amarenco P: Tako-Tsubo syndrome: A cardioembolic cause of brain infarction. Cerebrovasc Dis 29: 309– 310, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Shin SN, Yun KH, Ko JS, Rhee SJ, Yoo NJ, Kim NH, Oh SK, Jeong JW: Left ventricular thrombus associated with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a cardioembolic cause of cerebral infarction. J Cardiovasc Ultrasound 19: 152– 155, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Yonekawa K, Mussio P, Yuen B: Ischemic cerebrovascular stroke as complication of sepsis-induced Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Intern Emerg Med 6: 477– 478, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nakama Y, Maruhashi T, Kagawa E, Dai K: Incidence and treatment of left ventricular apical thrombosis in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 146: e58– e60, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Lee W, Profitis K, Barlis P, Van Gaal WJ: Stroke and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: is there more than just cause and effect?. Int J Cardiool 148: e37– e39, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Yaylali YT, Saricopur A: Takotsubo-syndrome presenting with supraventricular tachycardia, stroke, and thrombocytopenia. Int J Cardiol 161: e39– e41, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Kim SM, Aikat S, Bailey A, White M: Takotsubo cardiomyopathy as a source of cardioembolic cerebral infarction. BMJ Case Rep 2012: pii:bcr2012006835, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Matsuzono K, Ikeda Y, Deguchi S, Yamashita T, Kurata T, Deguchi K, Abe K: Cerebral embolic stroke after disappearing takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 22: e682– e683, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Lee VH, Connolly HM, Fulgham JR, Manno EM, Brown RD, Jr, Wijdicks EF: Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: an underappreciated ventricular dysfunction. J Neurosurg 105: 264– 270, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Lip GY, Lim HS: Atrial fibrillation and stroke prevention. Lancet Neurol 6: 981– 993, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Loh E, Sutton MS, Wun CC, Rouleau JL, Flaker GC, Gottlieb SS, Lamas GA, Moye LA, Goldhaber SZ, Preffer MA: Ventricular dysfunction and the risk of stroke after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 336: 251– 257, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, Sumner G, Hiralal R, Lonn E: Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a sytemic review. Eur Heart J 27: 1523– 1529, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Prasad A: Apical ballooning syndrome: an important differential diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 115: e56– e59, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]