Summary

The development of an embryo requires precise spatiotemporal regulation of cellular processes. During Drosophila gastrulation, a precise temporal pattern of cell division is encoded through transcriptional regulation of cdc25string in 25 distinct mitotic domains. Using a genetic screen, we demonstrate that the same transcription factors that regulate the spatial pattern of cdc25string transcription encode its temporal activation. We identify buttonhead and empty spiracles as the major activators of cdc25string expression in mitotic domain 2. The effect of these activators is balanced through repression by hairy, sloppy paired 1 and huckebein. Within the mitotic domain, temporal precision of mitosis is robust and is unaffected by changing dosage of rate-limiting transcriptional factors. Precision can, however, be disrupted by altering the levels of the two activators or two repressors. We propose that the additive and balanced action of activators and repressors is a general strategy for precise temporal regulation of cellular transitions during development.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

An organism undergoes major patterning events throughout its development. Precise temporal and spatial order is essential in developmental processes ranging from formation of somites in zebrafish (Giudicelli et al. 2007) to control of patterning gene expression in Drosophila (Stanojevic et al. 1991). Perturbations of these patterning events can be lethal (Nusslein-Volhard & Wieschaus 1980). Current models on the mechanisms of patterning mainly focus on the spatial aspect of this regulation, without addressing the precise control of temporal patterning. The temporal control of cell division during Drosophila gastrulation serves as an excellent model to study the mechanisms regulating temporal precision during embryonic development.

A newly fertilized Drosophila embryo undergoes 13 rapid synchronous nuclear divisions without intervening gap phases (Foe 1989). After the first 13 divisions, the cell cycle pauses in G2. Following this transition, cells divide in 25 distinct spatiotemporal mitotic domains (MD), (Foe 1989). The disruption of this temporal pattern significantly reduces the fitness of the organism (Edgar & O’Farrell 1990).

The precise patterning of division is achieved through transcriptional regulation of a Cdc25 phosphatase: cdc25string(Edgar et al. 1994). Cdc25string removes inhibitory phosphates on Cdk1 (the master regulator of mitosis) that are added by Wee1 and Myt1 kinases (Morgan 2007). The transcription of cdc25string in different MDs is regulated through many cis- regulatory elements spread over a >30 kb region (Lehman et al. 1999). The spatial regulation of cdc25string is achieved through a combination of patterning genes, including hunchback and buttonhead. Mutations in these and other patterning genes disrupt the spatial pattern of cdc25string transcription (Edgar et al. 1994). This disruption is mostly seen in the regions where the mutated gene is expressed. These observations suggest that each region of the embryo is established by a different set of genes, and that each set regulates a specific cis- regulatory element (Edgar et al. 1994; Lehman et al. 1999).

The aforementioned studies focused mainly on the regulation of spatial patterning, but the mechanisms encoding timing of cdc25string transcription are not well understood. We can envision two mechanisms controlling the temporal pattern. First, a dedicated set of temporal regulators control the temporal pattern of mitotic domains. These regulators could, for example, be expressed and act throughout the embryo. The different timing of mitotic domains could be imposed by having the patterning genes set different thresholds for the activation of cdc25string transcription. This scenario is similar to the regulation of the timing of the maternal-to-zygotic transition by a master regulators like Zelda (Zld) (Liang et al. 2008; Harrison et al. 2011). Zld controls the establishment of enhancers during early development through the entire embryo, and acts in collaboration with other factors to ensure proper spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression. The other possibility is that temporal patterning could be achieved through the rates that the appropriate spatial regulators accumulate in each MD. Distinguishing between these two models is not straightforward. Standard genetic approaches generate complete loss of gene products, producing results that can be difficult to interpret. These genetic manipulations often eliminate a mitotic domain entirely, or alter both its spatial and temporal pattern, precluding a definitive analysis of their effects on temporal patterning. To overcome this limitation, we performed a genetic screen using heterozygous embryos, thereby allowing for the identification of factors that act as rate-limiting regulators of cdc25string transcription and mitosis.

We undertook a whole-genome screen to identify dosage-sensitive regulators that impact temporal patterning of cdc25string in MD1 and 2. We find that different combinations of patterning genes- both activators and repressors - control the time of division in each region of the embryo. Changes in the dosage of single regulators only affects the timing and not the synchronicity of the division. However, altering the dosage of multiple regulators of the same domain does in fact affect both synchronicity and timing. We conclude that this combinatorial nature of temporal control ensures a robust timing of mitosis both within and between MDs.

Results

The timing of cell division in MD2 is determined by dosage of Buttonhead

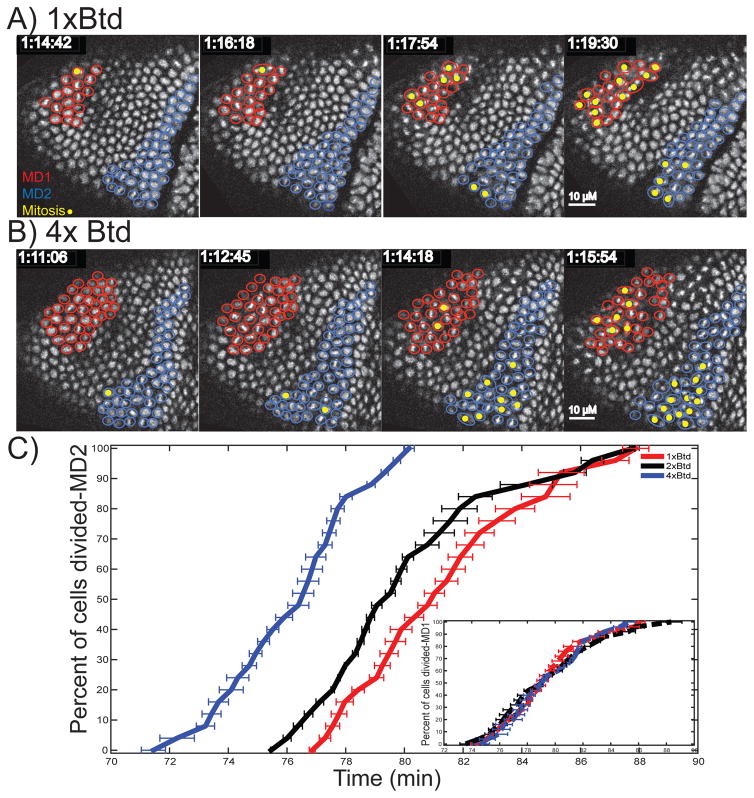

To test whether the spatial regulators also impact the temporal regulation of cdc25string transcription, we tested the role of Buttonhead (Btd) in setting the timing of expression of cdc25string MD2. At the onset of gastrulation, btd is expressed in a domain that roughly coincides with MD2 (Vincent et al. 1997). Consistent with a role for Btd in regulating the spatial pattern of MD2, MD2 is absent in btd mutants (Edgar et al. 1994). To determine whether Btd also has a direct role in regulating the timing of MD2, we examined the sensitivity of the division pattern to changes in btd expression levels. We recorded the cell division pattern in the anterior region of living embryos heterozygous for btd. Reducing the dosage of btd by half did not change the spatial pattern or number of cells in the domain, but this did result in a two minute delay in the initiation of mitosis in MD2. When the btd dosage is increased using a chromosome duplication covering btd, on average cells in MD2 divided three minutes earlier (Figure 1), indicating btd’s role in MD2 temporal control.

Figure 1. Btd acts through MD2 enhancer to regulate the MD2 temporal pattern.

(A and B) Cropped confocal images of the head region of an embryo expressing His2Av-RFP in a 1× Btd (A) and 4× Btd (B) background. Cells belonging to MD1 and MD2 are highlighted in red and blue, respectively. The cells undergoing division are marked yellow. C) Percentage of cells that have divided inside MD2 and MD1 (inset) as a function of time (minutes). The data was aligned at the time that 50% of MD1 has divided. The start time was normalized using WT data, around 74 min at 23°C.

The temporal pattern of cdc25string expression in MD2 is controlled by a combination of transcription factors

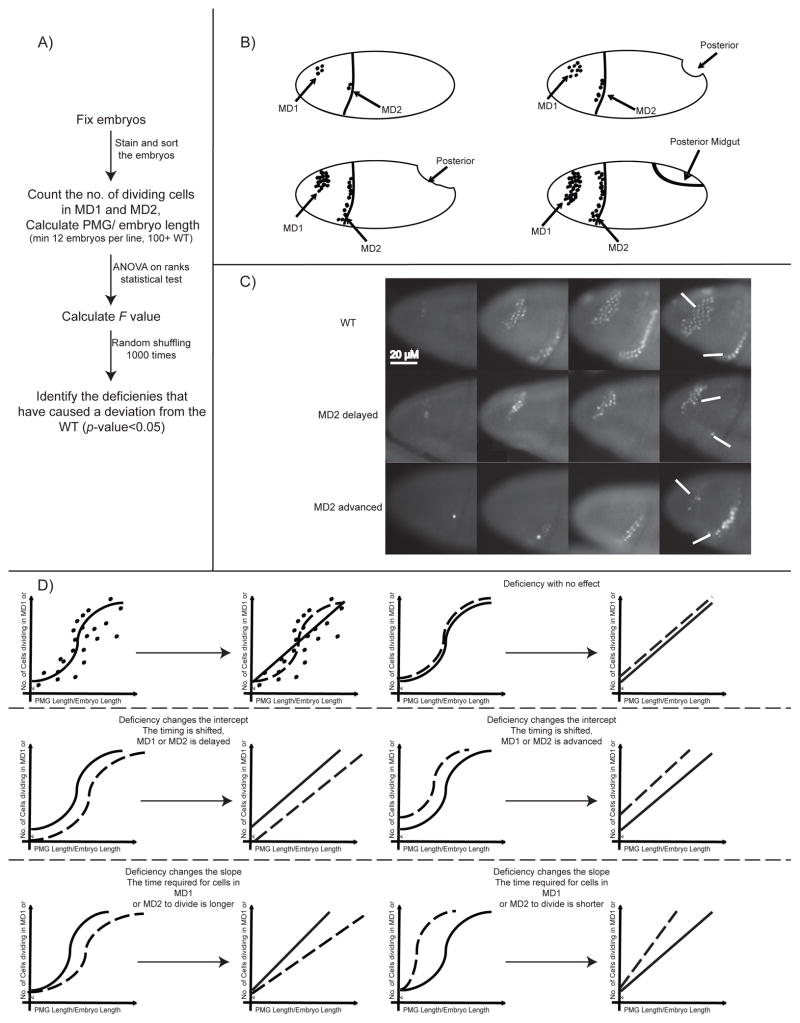

The sensitivity of MD2 timing to Btd dosage lead us to test whether there were other regulators with dosage effects on timing that could be identified using heterozygosity. To carry out a large-scale genomic screen for such regulators, we use 221 overlapping deficiencies that together span 85% of the Drosophila genome. For each deficiency, we mark mitotic cells in gastrulating heterozygous embryos (at least 12 embryos per genotype) with the phospho-histone H3 (phospho-H3) antibody. Using progression of the posterior midgut (PMG) as a marker for embryo age (Sweeton et al. 1991), we inferred the number of phospho-H3 positive cells in MD1 and 2 as a function of time (Figure 2). We then compare the dynamics observed in the heterozygous deficiencies to that observed in wild-type. Using ANOVA on ranks statistical test (see Supplemental Information for details), we measure the significance of the observed deviation in the progression of division in heterozygotes vs. WT embryos. The test is centered on the use of linear regression, which provides us with information on whether statistically significant deviations are due to a change in the intercept or the slope of the linear fit. Changes in these parameters have different biological interpretations. There are two different parameters associated with the temporal pattern of each domain: how many minutes after the start of cycle 14 each MD begins to divide (timing of the division) and how long it takes for all of the cells in the domain to divide (synchronicity/precision of the division). At room temperature, MD1, for example, divides at around 74 minutes into cycle 14 and it takes around 10 minutes for all of the cells in MD1 to divide (Di Talia & Wieschaus 2012). Changes in intercept indicate that the affected domain as a whole is dividing earlier or later (change in the timing of division). Changes in slope, on the contrary, imply that the time required for all the cells in the domain to complete mitosis has changed (change in the synchronicity of the division). We tested the method on btd and zld heterozygotes, which respectively are strong candidates for a spatially restricted regulator of timing (btd, see above) and a globally expressed one (zld). Zld controls the global regulation of patterning during mid blastula transition. In zld mutants, the transcription dynamics of many genes is severely disrupted during cleavage stages and cellularization stages (Harrison et al. 2011) but no effects have been reported on transcription during gastrulation. When btd heterozygotes are compared to wild-type, the linear fits for the two genotypes have similar slopes (p-value ~ 0.335), but different intercepts (p-value ~ 0.01). This observation confirms that heterozygosity of btd results in a later initiation of division in MD2 compared to WT. In zld heterozygotes, we did not detect any changes in the temporal pattern of MD1 or MD2 (Table S1), suggesting that Zelda dosage affects neither the timing of the division, nor its synchrony/precision.

Figure 2. Overview of the screen.

A) General scheme of the screen B) Schematic of an embryo in cycle 14. The cells undergoing mitosis are marked with an antibody against phospho-H3 (Ser10). C) Cropped still images of embryos undergoing mitosis in MD1 and MD2. The brightness of the images is increased for enhanced presentation. D) Number of cells dividing in MD1 or MD2 vs. PMG length/Embryo length can be used to calculate a linear fit. Deviation of the linear fit in WT vs. deficiency embryos can be due to shift in timing of MDs (intercept) or change in the mitosis rate (slope).

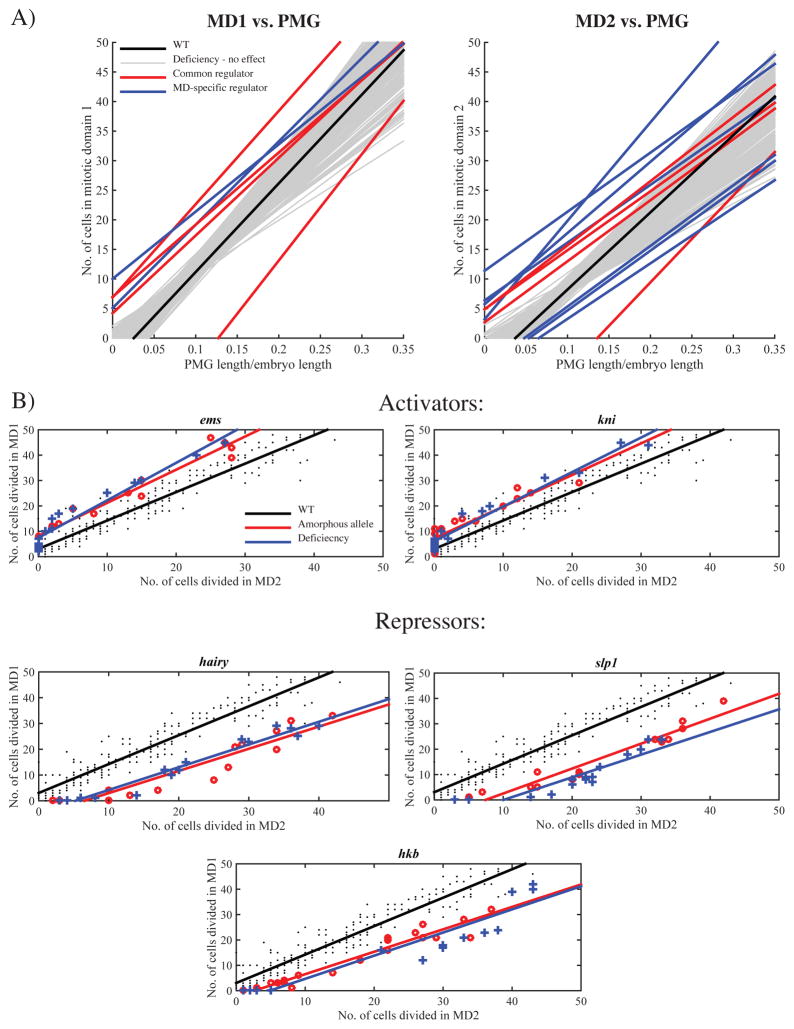

Our genetic screen uncovered 13 deficiencies that produced heterozygous embryos whose linear fits for either MD1 or MD2 deviated significantly from that of WT (p-value<0.05). The remaining 208 lines produced patterns and fits that were statistically indistinguishable from WT. In 12 of the 13 lines that affected mitotic timing, changes in the intercept were sufficient to explain the statistical significance, whereas in none of the 13 lines were changes in slope sufficient to explain the difference (Figure 3A, Figure S1, Table S1). This suggests that like btd, the identified regulators only alter when the domain begins to divide and do not change the time needed for all the cells in the MD to complete division. This unaltered synchronicity hints that the temporal pattern is very robust.

Figure 3. Heterozygosity of 13 deficiency lines affect the temporal pattern of MD1 or MD2.

A) Relative progression of mitosis in MD1 (left) and MD2 (right) versus PMG length/embryo length. B) The relative progression of mitosis in MD1 vs. MD2 in the mutants heterozygous for patterning gene in an identified chromosomal region (red line and “o”) shows the same deviation from the WT (black line and “.”) as the corresponding deficiency (blue line and “+”). See also Figure S1 and Table S1 and S2.

Four of the 13 deficiency lines had similar effects on timing in both MD1 and MD2, indicating that they might contain global regulators, acting throughout the entire embryo. One of these deficiencies includes the cdc25stringgene, and another covers wee1. Embryos heterozygous for null alleles in these two genes show the same effect as their respective deficiencies (data not shown), with halving cdc25string levels delaying and halving the wee1 levels advancing mitosis throughout the embryo. The other deficiencies affecting MD1 and MD2 both delayed mitosis. The two deficiencies overlap in the cytological map location 69F6–69F7, suggesting another regulator may lie within this region. Of the nine remaining deficiency lines, two affected only MD1 (both advance the temporal pattern of MD1 and both delete 66F5–67B1).

Seven lines were identified that affect the temporal pattern of MD2 and not MD1. These lines correspond to six different genomic regions. In the case of the deficiency covering cytological map location 49B2–49E2, we could not reconstitute the effect using smaller overlapping deficiencies that span the entire region, suggesting that the phenotype may be due to cumulative sub-threshold effects of multiple genes within the tested region (data not shown.) Each of the five remaining regions contained a single patterning gene known to affect cell fates in the anterior region of the embryo: sloppy paired 1 (slp1), hairy (h), knirps (kni), empty spiracles (ems) and huckebein (hkb), (Table S2). When tested as heterozygotes, amorphic alleles of each gene showed the same dosage-sensitive effect on MD2 timing as the corresponding deficiency lines. In all cases except slp1, heterozygosity of the mutant allele completely phenocopies the heterozygous deficiency effect on MD2 temporal pattern. Slp1 heterozygosity shows a weaker advancement of MD2 timing than that of the deficiency (Figure 3B), (p-value<10−3). This could be due to of complementary functions of slp1 and sloppy paired 2 (slp2), both of which map to the same region (Cadigan & Grossniklaus 1994). There are no available slp2 amorphic alleles to test this hypothesis.

Of the six regulators that specifically affect MD2 (btd, slp1, h, kni, ems and hkb), five have published expression patterns overlapping the domain, suggesting that they may directly control cdc25string expression. Although hkb does not show high levels of expression in MD2, it is possible that it exerts its effects at levels below experimental detection. In summary, we identified several patterning genes that affect the timing of MD2, suggesting that genes controlling the spatial pattern of mitotic domains also set the temporal pattern in a dosage-sensitive fashion.

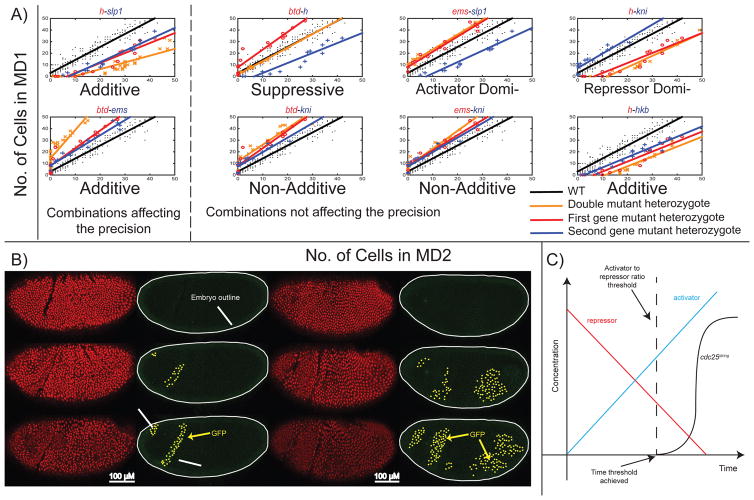

Some combinations of double mutant heterozygotes can alter the synchronicity

Of these 6 genes, slp1, h, kni and hkb are known repressors. Btd and ems are likely activators (Andrioli et al. 2002; Barolo & Levine 1997; Keller et al. 2000; Goldstein et al. 1999; Wimmer et al. 1997; Dalton et al. 1989). The observation that reduced dosage of btd, ems and kni delays mitosis suggests that, directly or indirectly, they activate transcription of cdc25string. Heterozygosity for the other three genes, slp1, h and hkb, advances the timing of division, suggesting that those genes may act as repressors. To test whether the apparent activators function at the same level in the regulatory process, we analyzed embryos heterozygous for the double mutant combinations btd-ems, btd-kni and ems-kni and compared their MD2 timing to single mutants (Figure 4A, Figure S2). The btd-ems double mutant combination showed an additive effect, with embryos showing a significantly increased mitotic delay over either single mutant. The btd-kni and ems-kni double mutant phenotypes, on the other hand, were equivalent to btd and ems alone, suggesting that Btd and Ems concentrations may directly determine timing of mitosis and that Kni may function at a different regulatory level (Table S3). A more direct regulatory role for Btd and Ems is also supported by experiments combining those alleles with repressors. In all six cases, the timing of division is either identical to that of heterozygotes for the single activator (called “activator dominant”), or the added heterozygosity for the activator eliminated the precocious mitosis associated with heterozygosity for the repressor and restored division to WT timing (called “Suppression”). Kni showed more complicated relationships with repressors, exhibiting WT phenotypes with slp1, and no effects on the single mutant h or hkb phenotypes. A similar analysis of the double mutant repressor combinations yields less clear distinctions regarding functional levels, although the strong additivity of the h and slp1 effects and their suppression by btd suggest that they may operate at a level close to the timer and different from that of hkb (Figure 4A, Figure S2). The dominant effect of ems on slp1 could have been attributed to the weaker phenotype of slp1 compared to the deficiency that includes both slp1 and slp2. But when we analyzed the double heterozygotes mutant of ems and the deficiency covering both slp1 and slp2, ems heterozygous was still dominant (data not shown).

Figure 4. Effects of double mutant heterozygotes on the temporal pattern of MD2.

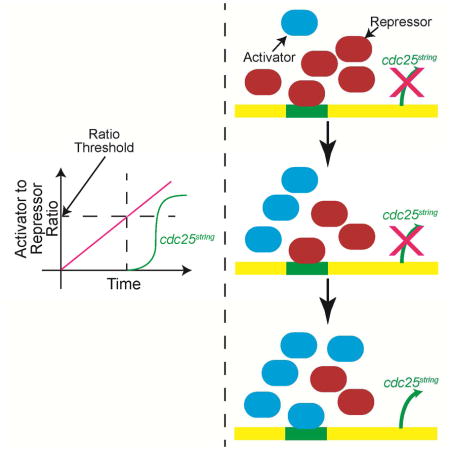

A) The effect of double mutant heterozygotes on number of cells dividing in MD2 vs. MD1. B) Confocal images of embryos expressing Btd ubiquitously and GFP under control of MD2 enhancer element. The expression of GFP is only limited in the head region under control of MD1, 2, 5 enh in WT embryos. When Btd is expressed ubiquitously, GFP is expanded to the abdomen. The images brightness is increased. C) Activator and repressors work together to set the temporal pattern of cdc25string. In our favored model, robust timing of cdc25string expression is achieved by integrating both the decline in repressors (red) and the increase in activators (blue). Transcription is initiated when the ratio of activators to repressors crosses a specific threshold (dotted line). See also Figure S2 and Table S3.

Out of the 15 possible combinations studied, only btd-ems and h-slp1 combinations affect the synchronicity/precision (measured by the change in the slope in the MD2vsPMG in Figure 4A), in addition to the timing of the division in MD2. In the case of btd-ems, the change in the slope indicates that it takes longer for MD2 to divide, and in h-slp1 double heterozygotes it takes less time for the whole domain to divide. Therefore, only in h-slp1 and btd-ems double heterozygotes, is the synchronicity of the temporal pattern affected significantly. This suggests that only a simultaneous alteration in the dosage of the two main activators and the two main repressors can affect the synchronicity of the temporal pattern. We suggest that the combinatorial action of multiple activators and multiple repressors allow a robust timing mechanism.

Ectopic expression of activators affects cdc25string transcription in multiple domains without altering cell fates in those domains

Although misexpression of head gap genes often leads to abnormalities in spatial patterning, uniform overexpression of either Btd or Ems in the anterior region on the embryo is compatible with viability and normal patterning of cell fates (Wimmer et al. 1997; Hartmann et al. 2010). To examine the effect of this ectopic expression on timing of mitosis, we used a ubiquitous GAL4 driver to express UAS-btd throughout the embryo. These embryos showed altered mitotic behavior that was not restricted to advances in division in MD2. Instead, the early timing and behavior normally associated with MD2 were now observed more broadly in the embryo. For example, cells in the region corresponding to MD5 in WT embryos divide at the same time as MD2, yielding a large domain of undetermined identity. Many domains in the abdomen (e.g. MD11) also divided earlier. Similar observations were obtained with uniform overexpression of Ems (data not shown). To investigate the molecular basis for the shift in mitosis timing following ubiquitous btd expression, we introduced into the ubiquitous Btd background a previously identified 6.6 kb transcriptional reporter expressing nuclear GFP (GFP-NLS) under the control of a cdc25string enhancer that drives expression in MDs 1, 2 and 5 (Lehman et al. 1999; Di Talia & Wieschaus 2012). In this line, unlike WT, GFP expression is not confined to the head region but extends to the abdomen (Figure 4B). This suggests that ectopic Btd advances mitosis by driving ectopic cdc25string expression through sequences present in the MD 1, 2, 5 enhancer. The non-uniform GFP expression argues that Btd is only able to drive cdc25string from this enhancer when certain other conditions are met. Regardless of the nature of those conditions, our results suggest that in the head region, where btd can drive ectopic mitoses without affecting cell fate, the primary role of Btd (and potentially Ems) may be to time cdc25string expression. That potential is maintained in the abdomen, where, however, ectopic expression of Btd has additional lethal effects on segmentation.

A small 500 bp enhancer controls the spatiotemporal pattern of MD2

The cis-regulating region of cdc25string is large (>30kb) with modules controlling the expression in specific regions of the embryo. Previous experiments identified a 6.6 kb region controlling expression of cdc25string in the head and trachea (Lehman et al. 1999). In order to pinpoint the MD2 enhancer, we tested fragments of this 6.6 kb region upstream of the endogenous cdc25string promoter and a GFP reporter. The smallest region that we have identified showing the same pattern as the endogenous cdc25string in MD2 is a 500 bp enhancer element, located at 5–5.5 kb <chr3R:29262841–29263340, BDGP R5/dm3>. This region is both sufficient and necessary to drive expression cdc25string in MD2 as well as in MD1. We could not separate the MD1 enhancer region from the MD2 cis-regulatory element (Figure S3).

Bioinformatic analysis (we used JASPAR to predict binding sites within the small enhancer (Wasserman & Sandelin 2004), using a relative profile threshold of 80%) and available ChiP/ChiP provide support for the idea that Hairy, Hkb, Btd and Ems might all bind to the enhancer, while Kni and Slp1 might not -see Table S4 and Kent et al. 2002; Bradley et al. 2010; Rosenbloom et al. 2015.

Discussion

The specification of different cell fates in both space and time (“patterning”) has been extensively studied in Drosophila embryos. Most studies have focused on the spatial aspects of cell fate specification, often under the tacit assumption that genes that control the spatial pattern also encode for the timing of cellular behaviors. Here, we provide direct and corroborating evidence for such an assumption. Furthermore, we show the activity of few trans-acting regulators is integrated at a cis-acting enhancer element to determine the time when the level of the regulators warrants the expression of cdc25string and commitment to mitosis. We propose that a detailed analysis of how the enhancer responds to the activity of the rate-limiting regulators identified here will provide insights on how cellular transitions are timed accurately during development.

We envisioned two possible models for obtaining a highly precise temporal pattern. In the first model, a universal timer gene X drives the expression of cdc25string in a concentration dependent manner. Gene X starts accumulating in mid cycle 14 and each MD is differentially sensitive to the levels of gene X. This sensitivity would depend on the patterning genes that have already established each of the MDs. In this model, the gene X’s dynamics directly determine when cdc25string is expressed and the patterning genes have a secondary role. The second model relies on the levels of the patterning genes themselves to regulate timing of cdc25string expression in each MD. In this model, the rates with which various patterning genes accumulate define when expression begins. In our experiments, we were not able to identify a candidate for gene X, which argues in favor of the second model.

In our proposed model, timing in each MD depends on its position in the embryo and thus on the dynamics of different sets of patterning factors. It is possible that the dynamics of their accumulation is sufficiently reproducible that mitosis in each domain is controlled with great accuracy. Alternatively, the dynamics of the individual transcriptional factors may be noisy, but the cdc25string enhancers have evolved combinatorial interactions that allow filtering out noise. This is an intriguing possibility, given the highly combinatorial nature of MD2 regulation demonstrated in this study. In this model the transcription of cdc25string is regulated like a switch and the concentrations of the activators (Ems and Btd) need to reach a threshold to turn the switch on in an additive fashion.

Btd and Ems are balanced by the activity of factors acting as transcriptional repressors, including h, slp1 and hkb. Based on published expression patterns, the levels of h and slp1, although decreasing, are still high at the onset of division in MD2 region. High expression levels of repressors at the time their targets are being expressed contrasts with the prevalent models where activators work synergistically to establish a pattern and repressors set the boundaries (Stanojevic et al. 1991). Therefore, we speculate that activators need to compete with repressors to initiate cdc25string transcription (Figure 4C). This newly identified mode of activity for repressors, balancing the activators, might not be limited to the regulation of cdc25string transcription temporal pattern. This type of regulation might be involved in establishing patterning throughout development. We hypothesize such mode of action was not detected previously because homozygous mutants often change the spatial information drastically. By using the heterozygous mutants, in combination with a rigorous quantitative method, we were able to uncover a more refined role of repressors in the regulation of developmental patterning.

The combinatorial mode of action, as substantiated by the change in the synchronicity of mitosis in btd-ems and h-slp1 double mutant heterozygotes, suggests that a fine, yet robust, balance of activation and repression encodes the observed precision and that to break such balance one needs to perturb significantly at least two regulators. Therefore, the system appears to have evolved to withstand perturbations of each component of the network and it is only by reducing the dosage of multiple major regulators that the precision of the system can be disrupted. By identifying the regulators as well as the cis-regulatory element for MD2, this study paves the way to describe the mechanism of the temporal patterning quantitatively by modulating the levels of the regulators and studying cdc25string transcription in vivo.

Experimental Procedures

Screen procedure

Embryos were fixed and stained with the proper antibodies. The number of cells undergoing mitosis in MD1 and 2 were counted using p-Histone H3 marker in the heterozygote deficiencies. Posterior midgut (PMG) progression is calculated by dividing the length of the embryo in A–P axis by the length of the PMG. A more detailed protocol can be found in the supplemental information.

Statistical test

In order to measure the significance of any deviation resulting from the heterozygosity, an ANOVA on ranks test was performed. Detailed description of the test can be found in the supplemental information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center for plasmids and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center for fly stocks. We thank David Robinson for designing the statistical test. We thank Shelby Blythe and Reba Samanta for help with experiments. We thank Trudi Schüpbach, Paul Schedl, Ned Wingreen, William Bialek, Julie Merkle, Shawn Little and Wieschaus and Schüpbach lab members for discussion. This work was supported by an NIH grant R00-HD074670 (S.D.). E.F.W. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

Conceptualization, A.M.R. and S.D. Methodology, A.M.R, S.D., E.W. Investigation, A.M.R., S.D. Writing, A.M.R, S.D, E.W. Supervision, S.D., E.W. Funding Acquisition, E.W.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andrioli LPM, et al. Anterior repression of a Drosophila stripe enhancer requires three position-specific mechanisms. Development. 2002;129(21):4931–4940. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barolo S, Levine M. hairy mediates dominant repression in the Drosophila embryo. The EMBO journal. 1997;16(10):2883–2891. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RK, et al. Binding Site Turnover Produces Pervasive Quantitative Changes in Transcription Factor Binding between Closely Related Drosophila Species G. A. Wray, ed. PLoS Biology. 2010;8(3):e1000343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan KM, Grossniklaus U. Functional redundancy: the respective roles of the two sloppy paired genes in Drosophila segmentation. Proceedings of the …. 1994 doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton D, Chadwick R, McGinnis W. Expression and embryonic function of empty spiracles: a Drosophila homeo box gene with two patterning functions on the anterior-posterior axis of the embryo. Genes & Development. 1989;3(12A):1940–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Talia S, Wieschaus EF. Short-Term Integration of Cdc25 Dynamics Controls Mitotic Entry during Drosophila Gastrulation. Developmental Cell. 2012;22(4):763–774. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, O’Farrell PH. The three postblastoderm cell cycles of Drosophila embryogenesis are regulated in G2 by string. Cell. 1990;62(3):469. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar BA, Lehman DA, O’Farrell PH. Transcriptional regulation of string (cdc25): a link between developmental programming and the cell cycle. Development. 1994;120(11):3131–3143. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.11.3131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE. Mitotic domains reveal early commitment of cells in Drosophila embryos. Development. 1989;107(1):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudicelli F, et al. Setting the Tempo in Development: An Investigation of the Zebrafish Somite Clock Mechanism A. Martinez Arias, ed. PLoS Biology. 2007;5(6):e150. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RE, et al. Huckebein repressor activity in Drosophila terminal patterning is mediated by Groucho. Development. 1999;126(17):3747–3755. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison MM, et al. Zelda Binding in the Early Drosophila melanogaster Embryo Marks Regions Subsequently Activated at the Maternal-to-Zygotic Transition G. P. Copenhaver, ed. PLoS Genetics. 2011;7(10):e1002266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann B, et al. Developmental Biology. Developmental Biology. 2010;340(1):125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller SA, et al. dCtBP-dependent and -independent repression activities of the Drosophila Knirps protein. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2000;20(19):7247–7258. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7247-7258.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ, et al. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome research. 2002;12(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman DA, et al. Cis-regulatory elements of the mitotic regulator, string/Cdc25. Development. 1999;126(9):1793–1803. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.1793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H-L, et al. The zinc-finger protein Zelda is a key activator of the early zygotic genome in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;456(7220):400–403. doi: 10.1038/nature07388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. The Cell Cycle: Principles of Control. 1. Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287(5785):795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom KR, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43(D1): D670–D681. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic D, Small S, Levine M. Regulation of a segmentation stripe by overlapping activators and repressors in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 1991;254(5036):1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1683715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeton D, et al. Gastrulation in Drosophila: the formation of the ventral furrow and posterior midgut invaginations. Development. 1991;112(3):775–789. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.3.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent A, Blankenship JT, Wieschaus E. Integration of the head and trunk segmentation systems controls cephalic furrow formation in Drosophila. Development. 1997;124(19):3747–3754. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman WW, Sandelin A. Applied bioinformatics for the identification of regulatory elements. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2004;5(4):276–287. doi: 10.1038/nrg1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer EA, et al. buttonhead does not contribute to a combinatorial code proposed for Drosophila head development. Development. 1997;124(8):1509–1517. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.