Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs), especially HDAC1, 2, 3 and 4, are abundantly expressed and over-activated in prostate cancer that is correlated with the poor prognosis. Thus, inhibition of HDAC activity has emerged as a potential alternative option for prostate cancer therapy. Chromopeptide A is a depsipeptide isolated from the marine sediment-derived bacterium Chromobacterium sp. HS-13-94; it has a chemical structure highly similar to FK228, a class I HDAC inhibitor that is approved by FDA for treating T-cell lymphoma. In this study, we determined whether chromopeptide A, like FK228, acted as a class I HDAC inhibitor, and whether chromopeptide A could inhibit the growth and migration of human prostate cancer in vitro and in vivo. HDAC enzyme selectivity and kinetic analysis revealed that chromopeptide A selectively inhibited the enzymatic activities of HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8 in a substrate non-competitive manner with comparable IC50 values for each HDAC member as FK228 in vitro. Importantly, chromopeptide A dose-dependently suppressed the proliferation of human prostate cancer cell lines PC3, DU145 and LNCaP with IC50 values of 2.43±0.02, 2.08±0.16, and 1.75±0.06 nmol/L, respectively, accompanied by dose-dependent inhibition of HDAC enzymatic activity in PC3 and DU145 cells. Chromopeptide A (0.2–50 nmol/L) caused G2/M phase arrest and induced apoptosis in the prostate cancer cell lines. Moreover, chromopeptide A dose-dependently inhibited the migration of PC3 cells. In mice bearing PC3 prostate cancer xenografts, intravenous injection of chromopeptide A (1.6, 3.2 mg/kg, once a week for 18 d) significantly suppressed the tumor growth, which was associated with increased expression levels of Ac-H3 and p21 in tumor tissues. Our results identify chromopeptide A as a novel class I HDAC inhibitor and provide therapeutic strategies that may be implemented in prostate cancer.

Keywords: HDAC, chromopeptide A, FK228, human prostate cancer, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, cancer cell migration, PC3 xenograft model

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most common malignancies in men, and its incidence is rapidly increasing worldwide1. Currently, androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) is the most prevalent option for prostate cancer therapy due to its intrinsic high dependence on androgen for tumor growth2,3. Unfortunately, most patients will inevitably progress to poor prognostic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) 2–3 years after previous ADT treatment, which introduces desperate therapeutic challenges in the clinic4. The current treatment regimen for CRPC mainly focuses on chemotherapy with docetaxel and cabazitaxel or androgen-receptor (AR) antagonists, including abiraterone and enzalutamide5,6,7. However, the overall response ratio for these drugs is rather limited, while acquired resistance shortly occurs in those cases that initially respond to treatment8,9,10,11. Therefore, the clinical treatment of CRPC remains unsatisfactory.

In recent years, new drugs for prostate cancer treatment have emerged. Histone deacetylases (HDACs), especially HDAC1, 2, 3 and 4, are abundantly expressed and over-activated in prostate cancer, which is correlated with the poor prognosis of patients12. In particular, overexpression and nuclear recruitment of HDACs results in accelerated cell proliferation, delayed cell differentiation and even more aggressive phenotypes of prostate cancer cells13,14. On the other hand, decreased proliferation and metastatic potential of prostate cancer cells have been observed in many preclinical studies upon the HDAC activity inhibition15,16. Therefore, HDAC targeting has been considered as a potential approach for treating prostate cancer. To date, many clinical studies with HDAC inhibitors have been conducted in the clinic for treating prostate cancer, showing partial response with an obvious prostate-specific antigen (PSA) decline in a subset of patients17,18,19.

Bacteria belonging to the genus Chromobacterium are known to be the main source of violacein, which shows important anti-tumor, anti-microbial, and anti-parasitic activities20. C violaceum is the most commonly studied bacterium due to FK228 isolation, which is a class I HDAC inhibitor that is approved by FDA for treating T-cell lymphoma21. Chromopeptide A is a depsipeptide purified from the marine sediment-derived bacterium Chromobacterium sp. HS-13-94, which has a very similar structure to FK22822. In this study, we aimed to elucidate whether Chromopeptide A exhibits anti-prostate cancer activity via targeting HDAC and thus provides an alternative therapeutic option that may be implemented in prostate cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

Human prostate cancer cell lines, PC3, DU145 and LNCaP, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cell lines were authenticated by short tandem repeat (STR) fingerprinting and were maintained in culture medium according to the supplier's instructions.

FK228 was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Shanghai, China). Chromopeptide A was purified as previously reported22. Both compounds were dissolved with DMSO to 10 mmol/L as stock solutions and stored at -20 °C before use.

HDAC enzyme selectivity profiling

HDAC in vitro enzyme activity was determined by the protease-coupled assay. Different concentrations of compounds (20, 4, 0.8, 0.16, 0.032 and 0.0064 nmol/L) were incubated with full-length recombinant HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, and HDAC6 (BPS Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) or fragments of HDAC4, HDAC5, and HDAC7 (BPS Biosciences) at room temperature for 15 min, which was followed by adding trypsin as well as Ac-peptide-AMC substrates to initiate a reaction in Tris-based assay buffer. Reaction mixtures were incubated for 60 min at room temperature, which was followed by adding a stop solution containing trypsin. For HDAC8, Ac-peptide-AMC substrate was added to the enzyme/compound mix and incubated for 4 h at room temperature. The coupled reaction was incubated for another 90 min at 37 °C. Fluorescent AMC released from substrate was measured using filter sets, such as excitation=355 nm and emission=460 nm. IC50 values were calculated by GraphPad Prism software (California, CA, USA).

Kinetic analysis on HDAC1

Compounds were diluted to the indicated concentrations and transferred into a 384-well microtiter plate to obtain the final concentrations, which were 2×IC50, IC50, and 1/2×IC50. Ac-peptide-AMC substrate was serially diluted (dilution factor=2) in Tris-based assay buffer for an 11-point dilution series with a final concentration of 400 μmol/L. A reaction was initiated by the addition of serially diluted substrate solutions. Data were fitted by the mixed competitive inhibition model in GraphPad Prism software to predict the Ki and alpha values.

Cell-based HDAC activity assay

Cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of compounds for another 24 h. Then, protein was extracted with NP-40 lysis buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China), and lysates were quantitated with a BCA Protein Quantitation Kit (Beyotime, Haimen, China). HDAC activity in different cell extracts was measured using a Fluorimetric HDAC Activity Assay Kit (AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 3000–6000 cells/well in triplicate. After 24 h, the cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of compounds and were cultured for another 72 h. Then, the cells were fixed with 10% trichloroacetic acid overnight and stained with 4 mg/mL sulforhodamine B (SRB, Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in 1% acetic acid. The SRB in the cells was dissolved in 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl and measured at 560 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded into 12-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well. After attachment, the cells were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of compounds for 24 h. Both adherent and floating cells were harvested and fixed in cold 70% ethanol at 4 °C overnight. Prior to FACS analysis, cells were washed with cold PBS and re-suspended in PBS containing propidium iodide (100 mg/mL) and RNase A (20 mg/mL). Then, cells were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in the dark. Quantitation of the cell cycle distribution was evaluated using a Becton-Dickinson FACS Calibur flow cytometer and Modifit LT software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Cell apoptosis analysis

Cells were cultured in 12-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were treated with DMSO or indicated concentrations of compounds for 48 h. Then, both adherent and floating cells were harvested and washed with cold PBS. Prior to FACS analysis, cells were re-suspended in 500 μL of binding buffer containing 5 μL of annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of PI solution (BD Biosciences), and they were then stained for 15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, apoptosis analysis was performed using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using CELLQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Immunoblotting

Protein extracts were prepared with the SDS-lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2% SDS) after washing twice with cold PBS. Then, cell lysates were boiled for 10 min and centrifuged at 14 000×g at 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and subsequently resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, probed with the appropriate primary antibodies and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. The immunoreactive proteins were detected using an ECL plus detection reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and imaged by autoradiography. Antibodies used in immunoblotting were as follows: p21 (#2947, Cell Signaling Technology, CST, Boston, MA, USA), Acetyl-Histone H3 (#9649, CST), Histone H3 (#9715, CST), phospho-cdc2 (#4539, CST), cdc2 (#9116, CST), phospho-cdc25C (#4901, CST), cdc25C (#4688, CST), PARP (#9542, CST), cleaved PARP (#5625, CST), caspase 3 (#9662, CST), and cleaved caspase 3 (#9661, CST).

Migration assay

PC3 cells were seeded into the upper chambers of the 24-well transwell chambers (Corning, New York, NY, USA) at a density of 1×104 cells/well with media containing 1% FBS, and media with 5% FBS was added to the lower chambers. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of compounds for 24 h and were then fixed and stained with 5% crystal violet solution. The inserts were washed and the cells on the upper side were removed using a cotton swab. The number of migrated cells was counted under a microscope.

Animal studies

Four- to six-week-old nu/nu athymic BALB/c mice were obtained from the Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). All studies were conducted in compliance with guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica. PC3 cells (5×106 cells/200 μL F12 medium) were subcutaneously inoculated into the right flanks of nude mice. The tumor sizes were measured by calipers and tumor volume (TV) was calculated as follows: TV=1/2×a×b2 (a and b represent the length and width of the tumor, respectively). When the TV reached 100–150 mm3, the mice were randomly assigned to control and treatment groups (n=6 per group). For efficacy studies, mice bearing PC3 cells were treated with the indicated doses of chromopeptide A or FK228 dissolved in saline containing 10% castor oil once a week via intravenous injection. The TV and body weight (g) were measured every 3 d. The individual relative tumor volume (RTV) was calculated as follows: RTV=Vt/V0, where Vt is the volume on each day and V0 represents the volume at the beginning of the treatment. The RTV was shown on the indicated days as the mean±SEM indicated for groups of mice. To the endpoint, tumors were harvested and lysed in cold RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Haimen, China) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for immunoblotting analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as the mean±SD, and significance was determined by Student's t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant for P<0.05 and P<0.01. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software.

Results

Chromopeptide A is a selective class I HDAC inhibitor

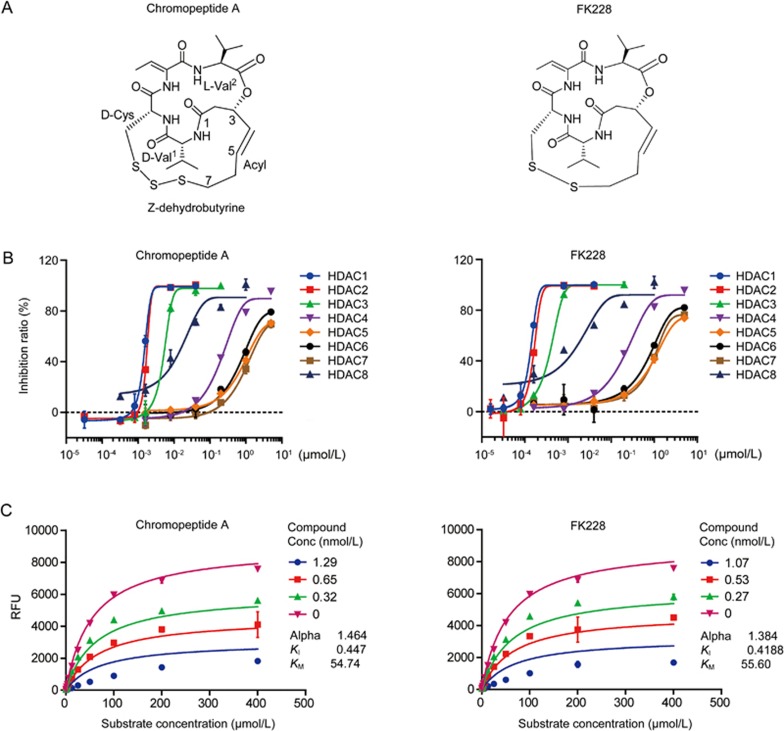

Because the chemical structure of chromopeptide A is highly similar to FK228 (Figure 1A), we investigated whether chromopeptide A could selectively inhibit the activity of class I HDACs. Using a protease-coupled assay, the pharmacological effects of chromopeptide A, along with FK228, on HDAC1–8 were profiled. We found that chromopeptide A only exerted potent inhibition on HDAC1, 2, 3 and 8; while it had minimal inhibition activity on HDAC4, 5, 6, and 7, which was exactly the same as FK228 (Figure 1B). These findings suggested that chromopeptide A is a selective inhibitor of class I HDACs with comparable IC50 values for each HDAC member as FK228 in vitro.

Figure 1.

Chromopeptide A is a novel class I HDAC inhibitor. (A) Chemical structures of chromopeptide A and FK228. (B) Selectivity profiling on HDAC enzymes of chromopeptide A and FK228. The indicated concentrations of chromopeptide A and FK228 were exposed to HDAC1-8 and the enzyme activity was determined by the protease-coupled assay. Bars represent the mean±SD. (C) Kinetic analysis of chromopeptide A and FK228 on HDAC1. Chromopeptide A and FK228 were exposed to different concentrations of Ac-peptide-AMC substrates with HDAC1. The alpha values and Ki values were determined in a mixed competitive inhibition fitted model. Bars represent the mean±SD.

HDAC inhibitors could act in either competitive or noncompetitive substrate modes. We thus took HDAC1 as an example to investigate the kinetic characteristics of chromopeptide A. To this end, a standard substrate concentration-response assay was performed, and the alpha values were determined. We found that the alpha values for chromopeptide A and FK228 were 1.464 and 1.384, respectively. These results indicated that chromopeptide A, as well as FK228, exhibited a non-competitive inhibition mode with respect to the HDAC substrate (Figure 1C).

Chromopeptide A inhibits prostate cancer cell proliferation via targeting HDAC

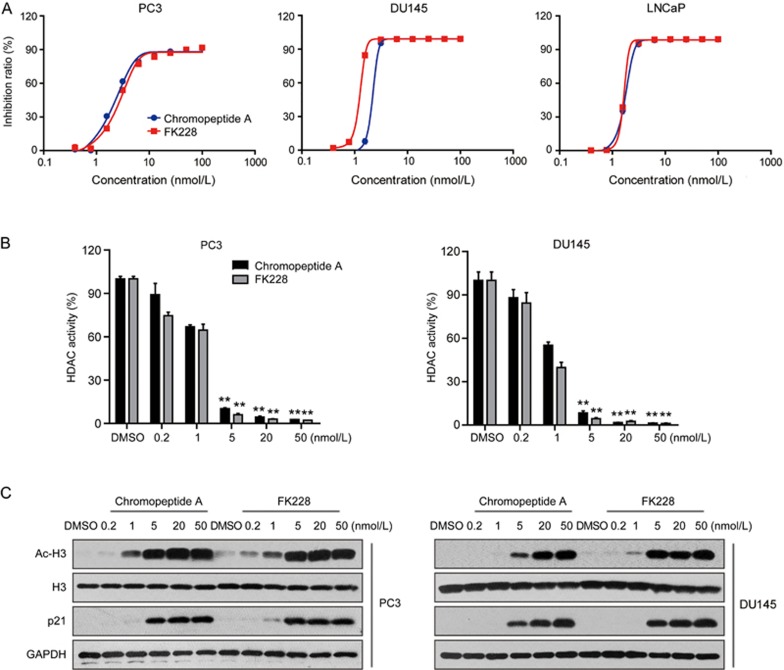

Due to the important role of HDACs in the development and progression of prostate cancer, we evaluated whether chromopeptide A can suppress the cell proliferation of prostate cancer cells. Three prostate cancer cell lines, PC3, DU145 and LNCaP, were selected. All cell lines showed exquisite sensitivity to chromopeptide A treatment, with IC50 values of 2.43±0.02, 2.08±0.16, and 1.75±0.06 nmol/L, respectively (Figure 2A). Next, we tested whether chromopeptide A-induced inhibition is in HDAC-dependent manner. As shown in Figure 2B, chromopeptide A treatment strongly decreased HDAC enzymatic activity in PC3 and DU145 cells in a dose-dependent manner, similar to that of FK228.

Figure 2.

Chromopeptide A impacts the viability of prostate cancer cells through targeting HDAC. (A) Effects of chromopeptide A and FK228 on cell proliferation. Prostate cancer cell lines PC3, DU145 and LNCaP were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 at the indicated concentrations for 72 h. Cell viability was assessed with the SRB assay. Bars represent the mean±SD. (B, C) Effects of chromopeptide A and FK228 on HDAC activity inhibition. PC3 and DU145 were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 (0.2, 1, 5, 20, and 50 nmol/L) for 24 h. HDAC activity was measured (B) and the substrate of class I HDAC was detected with immunoblotting (C). Bars represent the means±SD. **P<0.01.

Histones are the primary substrates for HDAC1, 2 and 3. Meanwhile, HDAC1 is a repressor of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 by directly binding to the Sp1 sites of p21 promoter23,24. Thus, the acetylation of histones and expression of p21 are two well-established indicators for class I HDAC inhibition. Herein, we found remarkably up-regulated acetylation of H3 and expression of p21 after chromopeptide A or FK228 treatment (Figure 2C). These data indicated that chromopeptide A inhibits the activity of class I HDACs and impairs the cell viability of prostate cancer cells.

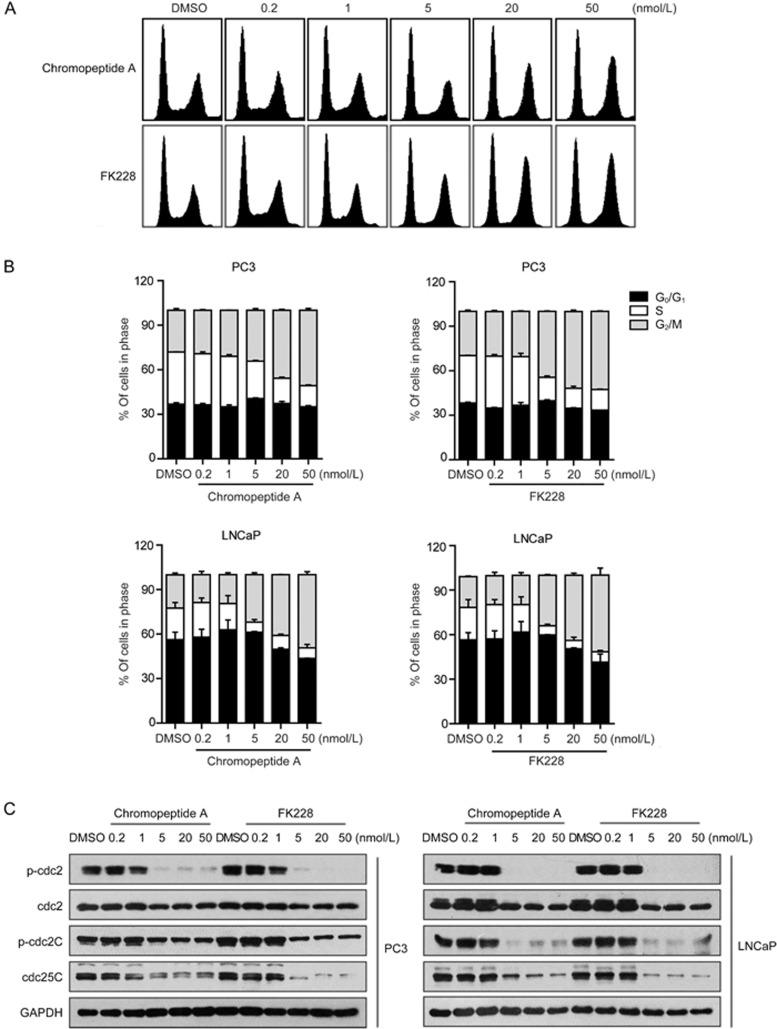

Chromopeptide A induces G2/M phase arrest via inhibiting phosphorylation of cdc2 and cdc25C

Next, we investigated the mechanisms underlying the cell proliferation inhibition in prostate cancer induced by chromopeptide A. For this, PC3 and LNCaP cells were exposed to different concentrations of chromopeptide A or FK228 (0, 0.2, 1, 5, 20, and 50 nmol/L) for 24 h; then, the cell cycle distribution was determined by flow cytometry. We found that both chromopeptide A and FK228 treatment, at given concentrations, exhibited G2/M phase arrest in PC3 and LNCaP cells (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Chromopeptide A induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in prostate cancer cells. (A) Effects of chromopeptide A and FK228 on cell cycle distribution. PC3 and LNCaP cells were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 at the indicated concentrations for 24 h. The cell cycle distribution was analyzed by FACS after propidium iodide staining. Quantification results are presented. Bars represent the mean±SD. (B) Impacts of chromopeptide A and FK228 on G2/M transition regulators. PC3 and LNCaP cells were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 at indicated concentrations for 24 h, and cells lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Because cdc2 and cdc25C are the two key regulators of G2/M transition, we thus investigated whether chromopeptide A or FK228 affects cdc2 and cdc25C. For this, we performed immunoblotting and found that chromopeptide A or FK228 significantly suppressed the phosphorylation of cdc2 and cdc25C in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3C). These data suggested that chromopeptide A induces G2/M phase arrest in prostate cancer cells through inhibiting the phosphorylation of cdc2 and cdc25C.

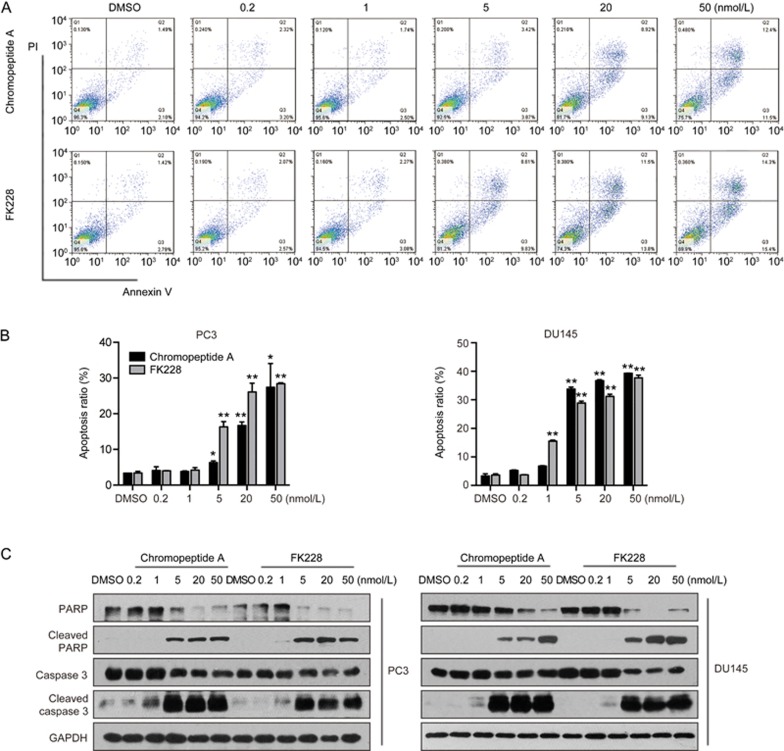

Chromopeptide A induces cell apoptosis via the caspase-dependent manner

Cell apoptosis is one of the major events that induces cell death. Next, we are particularly interested in whether chromopeptide A or FK228 induced cell death via apoptosis-inducing manner. To this end, PC3 and DU145 cells were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 at indicated concentrations (0, 0.2, 1, 5, 20 and 50 nmol/L) for 48 h and were then collected for analyses using the annexin V/PI assay. We found that both chromopeptide A and FK228 induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner (Figures 4A and 4B). Moreover, cleavage of PARP and caspase 3, the hallmarks of apoptotic events, was noted to be up-regulated in prostate cancer cells upon treatment with chromopeptide A or FK228 (Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure 1). These data suggested that chromopeptide A induced apoptosis in prostate cancer via a caspase-dependent pathway.

Figure 4.

Chromopeptide A induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. (A, B) Effects of chromopeptide A on apoptosis induction. PC3 and DU145 cells were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 at indicated concentrations for 48 h. Apoptosis was determined with the annexin-V/PI assay (A). Bars represent the mean±SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Cell lysis was analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (B).

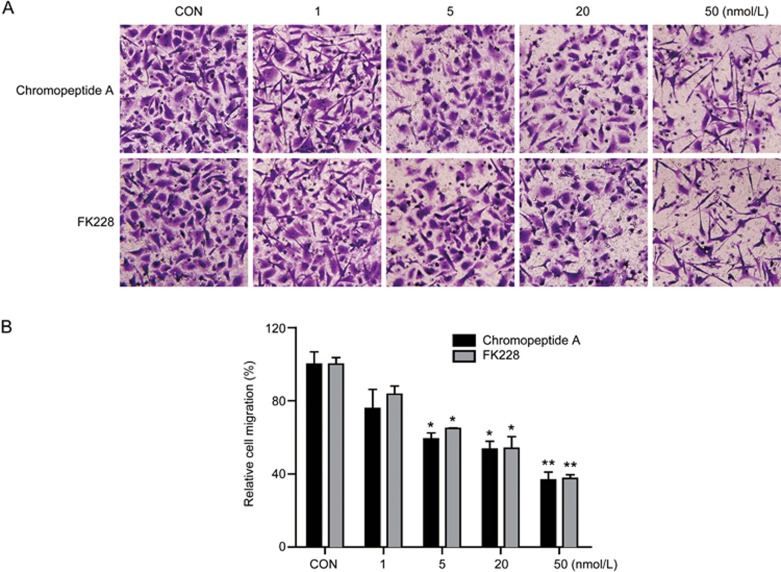

Chromopeptide A inhibits the migration of prostate cancer cells

Cell migration is the leading cause of tumor metastasis. To explore whether chromopeptide A could inhibit cell migration, we performed a transwell assay on PC3 cells. Various concentrations of chromopeptide A or FK228 (0, 1, 5, 20, and 50 nmol/L) were applied to PC3 cells for 24 h. We found that chromopeptide A or FK228 dramatically and dose-dependently inhibited cell migration, as evidenced by the findings that fewer cells migrated to the lower side of the chamber (Figures 5A and 5B). These results indicated that chromopeptide A impairs the migratory capability of prostate cancer cells.

Figure 5.

Chromopeptide A impairs prostate cancer cell migration in a dose-dependent manner. (A, B) PC3 cells were planted in the upper transwell chamber and treated with indicated concentrations of chromopeptide A or FK228. Cells were allowed to migrate for 24 h; then, migrated cells were stained and observed under a microscope (×200) (A) and cell numbers were counted (B). Bars represent the mean±SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

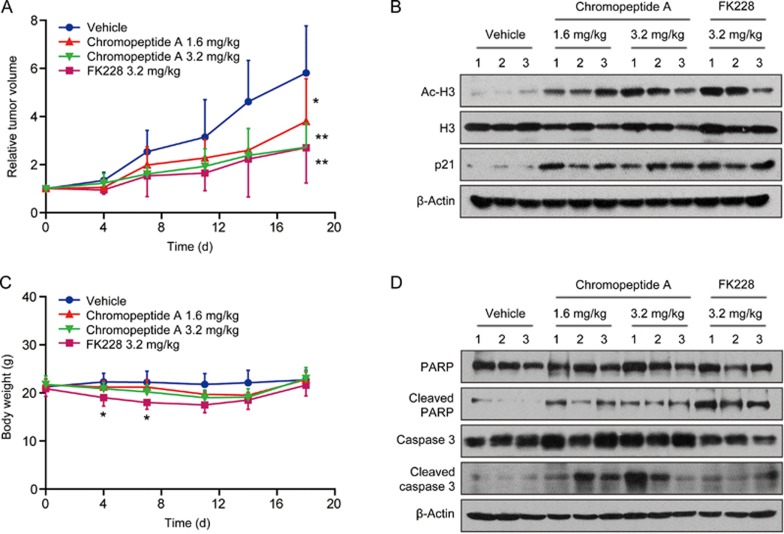

Chromopeptide A suppresses the tumor growth of the PC3 xenograft model

The therapeutic potential of chromopeptide A via targeting class I HDACs was further assessed in PC3 xenografts. Mice bearing PC3 xenografts were randomly divided into the following 4 experimental groups: chromopeptide A-high (3.2 mg/kg, once a week), chromopeptide A-low (1.6 mg/kg, once a week), FK228-high (3.2 mg/kg, once a week) and vehicle group (saline containing 10% castor oil, once a week). Remarkable inhibition of tumor growth was observed in all experimental groups upon treatment with HDAC inhibitors compared with the vehicle group (Figure 6A). The enhanced tumor growth inhibition was associated with increased expression levels of Ac-H3 and p21 (Figure 6B). In addition, we monitored the body weight of mice across the treatment conditions. Slight loss of body weight was observed in all treated groups. However, a statistically significant loss in the high dose FK228 treatment group was observed compared with the chromopeptide A high dose group for the first two weeks, implying a better tolerance to chromopeptide A than to FK228 (Figure 6C). Finally, apoptosis-associated proteins, PARP and caspase 3, were detected within tumors by immunoblotting. As shown, the cleavage of PARP and caspase 3 was up-regulated after treatment with chromopeptide A or FK228, indicating that apoptosis was induced after drug treatment (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Chromopeptide A inhibits PC3 tumor growth in vivo. (A) Tumor growth inhibition in chromopeptide A-treated PC3 xenografts. Mice bearing PC3 cells were treated with chromopeptide A or FK228 (iv, once a week) for 18 d after the tumor volume reached 100–150 mm3. Tumor volumes were measured every three days and are presented as the average relative tumor volume±SD. The percentage of tumor volume inhibition was measured compared with the vehicle group. Bars represent the mean±SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. (B) Effects of chromopeptide A on in vivo protein expression modulation. Mice were humanely euthanized, and protein extracts from tumor tissues were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies. (C) The body weight was determined, and the 3.2 mg/kg FK228 group was compared with the 3.2 mg/kg chromopeptide A group. Bars represent the mean±SD. *P<0.05. (D) Effects of chromopeptide A on inducing apoptosis in vivo. Protein extracts from tumor tissues were subjected to immunoblotting analysis with the indicated antibodies.

Discussion

Histone modifications, including acetylation and deacetylation, are the major driving force for epigenetic gene regulation25. As a key enzyme responsible for this process, HDAC plays an indispensable role in cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and migration. In mammals, a total of 18 HDACs have been identified and grouped into four classes: class I (HDACs 1–3 & 8), class II (HDACs 4–7 and HDACs 9–10), class III (Sirt1-Sirt7) and class IV (HDAC11)26. Deregulation in the expression of HDAC enzymes has been implicated in cancer development for several decades27. In prostate cancer, class I HDACs were particularly overexpressed and associated with poor clinical outcomes14. As a result, the class I HDAC is becoming a promising specific target for prostate cancer therapy.

Dozens of HDAC inhibitors have been developed in recent years28. To date, 5 drugs targeting HDAC, including SAHA (Vorinostat), FK228 (Romidepsin), LBH-589 (Panobinostat), PXD101 (Belinostat) and HBI-8000 (Childamide), have been approved worldwide to treat hematological malignancy subtypes29. Several clinical trials are ongoing, including but not limited to these five drugs, to expand the application of HDAC inhibitors to solid tumors, especially prostate cancer. However, minimal clinical activity was achieved in these clinical trials30.

In this study, we first identified chromopeptide A as a selective class I HDAC inhibitor and further demonstrated that chromopeptide A significantly suppressed prostate cancer growth both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistic insights have shown that such class I inhibition led to the induction of G2/M cell cycle arrest as well as of cell apoptosis associated with enhanced expression of Ac-H3 and p21.

Because FK228 is also a class I HDAC inhibitor, its efficacy on prostate cancer growth has been compared accordingly. Our data suggested that chromopeptide A and FK228 exhibited similar potency and comparable pharmacological efficacy on prostate cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, both chromopeptide A and FK228 led to G2/M phase arrest rather than G1/S phase arrest induced by a pan HDAC inhibitor31,32. We further noted that chromopeptide A and FK228 could inhibit cell migration, implicating the potential beneficial effects of chromopeptide A and FK228 on prostate cancer metastasis. These findings help identify the mechanism-based differentiation of class I HDAC inhibitors from pan HDAC inhibitors.

In conclusion, this is the first demonstration that chromopeptide A is a potent inhibitor of class I HDACs with a promising efficacy on tumor growth and metastasis for prostate cancer both in vitro and in vivo. Notably, in vivo data demonstrated a better tolerance of chromopeptide A on body weight than FK228, implicating the controllable toxicity of chromopeptide A in prostate cancer therapy.

Author contribution

Ai-jun SHEN and Jing-ya SUN designed the study; Jing-ya SUN, Xin WANG, Hong-chun LIU, Min-min ZHANG, Yu-Chih LIU, Chen-hua ZHANG, Yi SU, and Yan-yan SHEN performed the research and analyzed the data; Ji-dong WANG and Yue-wei GUO provided the compound chromopeptide A; Jing-ya SUN, Ai-jun SHEN, and Mei-yu GENG drafted the manuscript; and Mei-yu GENG, Ai-jun SHEN, and Yue-wei GUO provided supervision.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No 81673472, No 81402966 to Ai-jun SHEN and 81520108028 to Yue-wei GUO); the National Program on Key Basic Research Project of China (No 2012CB910704 to Mei-yu GENG); and the Personalized Medicines-Molecular Signature-Based Drug Discovery and Development, Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No XDA12020105 to Ai-jun SHEN).

Footnotes

Supplementary information is available at the website of Acta Pharmacologica Sinica.

Supplementary Information

Chromopeptide A induces apoptosis through caspase 9 dependent intrinsic pathway in prostate cancer cells.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. Ca-Cancer J Clin 2016; 66: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe S, Colditz GA. Prostate cancer: is it time to expand the research focus to early-life exposures? Nat Rev Cancer 2013; 13: 208–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi N, Gulley JL, Dahut WL. Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. JAMA 2005; 294: 238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap TA, Smith AD, Ferraldeschi R, Al-Lazikani B, Workman P, de Bono JS. Drug discovery in advanced prostate cancer: translating biology into therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016; 15: 699–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karantanos T, Corn PG, Thompson TC. Prostate cancer progression after androgen deprivation therapy: mechanisms of castrate resistance and novel therapeutic approaches. Oncogene 2013; 32: 5501–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol 2011; 59: 572–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1995–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1502–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthold DR, Pond GR, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock IF. Survival and PSA response of patients in the TAX 327 study who crossed over to receive docetaxel after mitoxantrone or vice versa. Ann Oncol 2008; 19: 1749–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadiminty N, Tummala R, Liu C, Yang J, Lou W, Evans CP, et al. NF-kappaB2/p52 induces resistance to enzalutamide in prostate cancer: role of androgen receptor and its variants. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12: 1629–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostaghel EA, Marck BT, Plymate SR, Vessella RL, Balk S, Matsumoto AM, et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 5913–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltregny D, North B, Van Mellaert F, de Leval J, Verdin E, Castronovo V. Screening of histone deacetylases (HDAC) expression in human prostate cancer reveals distinct class I HDAC profiles between epithelial and stromal cells. Eur J Histochem 2004; 48: 273–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkidou K, Gaughan L, Cook S, Leung HY, Neal DE, Robson CN. Upregulation and nuclear recruitment of HDAC1 in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Prostate 2004; 59: 177–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichert W, Roske A, Gekeler V, Beckers T, Stephan C, Jung K, et al. Histone deacetylases 1, 2 and 3 are highly expressed in prostate cancer and HDAC2 expression is associated with shorter PSA relapse time after radical prostatectomy. Br J Cancer 2008; 98: 604–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LH, Zhang PR, Cai PY, Li ZC. Histone deacetylase inhibitor, Romidepsin (FK228) inhibits endometrial cancer cell growth through augmentation of p53-p21 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother 2016; 82: 161–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscetti M, Dadashian EL, Guo W, Quach B, Mulholland DJ, Park JW, et al. HDAC inhibition impedes epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity and suppresses metastatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer. Oncogene 2016; 35: 3781–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster PN, Marchion D, Thomas S, Egorin M, Minton S, Springett G, et al. Phase I trial of vorinostat and doxorubicin in solid tumours: histone deacetylase 2 expression as a predictive marker. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 1044–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley D, Rathkopf D, Dunn R, Stadler WM, Liu G, Smith DC, et al. Vorinostat in advanced prostate cancer patients progressing on prior chemotherapy (National Cancer Institute Trial 6862): trial results and interleukin-6 analysis: a study by the department of defense prostate cancer clinical trial consortium and university of chicago phase 2 consortium. Cancer 2009; 115: 5541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molife LR, Attard G, Fong PC, Karavasilis V, Reid AH, Patterson S, et al. Phase II, two-stage, single-arm trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) romidepsin in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran N, Justo GZ, Ferreira CV, Melo PS, Cordi L, Martins D. Violacein: properties and biological activities. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2007; 48: 127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderMolen KM, McCulloch W, Pearce CJ, Oberlies NH. Romidepsin (Istodax, NSC 630176, FR901228, FK228, depsipeptide): a natural product recently approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2011; 64: 525–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Wang X, Zhang H, Sun J, Zheng L, Liu H, et al. Chromopeptide A, a highly cytotoxic depsipeptide from the marine sediment-derived bacterium Chromobacterium sp. HS-13-94. Acta Pharm Sin B 2015; 5: 62–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocker M, Schneider-Stock R. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: signalling towards p21cip1/waf1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007; 39: 1367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gui CY, Ngo L, Xu WS, Richon VM, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor activation of p21WAF1 involves changes in promoter-associated proteins, including HDAC1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101: 1241–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minucci S, Pelicci PG. Histone deacetylase inhibitors and the promise of epigenetic (and more) treatments for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6: 38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas A, Gupta S. The role of histone deacetylases in prostate cancer. Epigenetics 2008; 3: 300–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer 2001; 1: 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane AA, Chabner BA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 5459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suresh PS, Devaraj VC, Srinivas NR, Mullangi R. Review of bioanalytical assays for the quantitation of various HDAC inhibitors such as vorinostat, belinostat, panobinostat, romidepsin and chidamine. Biomed Chromatogr 2017; 31. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik D, Vashistha V, Isharwal S, Sediqe SA, Lin MF. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in castration-resistant prostate cancer: molecular mechanism of action and recent clinical trials. Ther Adv Urol 2015; 7: 388–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Ding K, Li L, Liu H, Wang Y, Liu C, et al. A novel histone deacetylase inhibitor Chidamide induces G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Biomed Pharmacother 2016; 83: 1032–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue K, Gu JJ, Zhang Q, Mavis C, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Czuczman MS, et al. Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, promotes cell cycle arrest and re-sensitizes rituximab- and chemo-resistant lymphoma cells to chemotherapy agents. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2016; 142: 379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Chromopeptide A induces apoptosis through caspase 9 dependent intrinsic pathway in prostate cancer cells.