Abstract

Emerging research suggests that both perceptions of discrimination and internalized racism (i.e., endorsement of negative stereotypes of one’s racial group) are associated with poor mental health. Yet, no studies to date have examined their effects on mental health with racial/ethnic minorities in the US in a single study. The present study examined: (a) the direct effects of everyday discrimination and internalized racism on risk of DSM-IV criteria of past-year major depressive disorder (MDD); (b) the interactive effects of everyday discrimination and internalized racism on risk of past-year MDD; and (c) the indirect effect of everyday discrimination on risk of past-year MDD via internalized racism. Further, we examined whether these associations differed by ethnic group membership. We utilized nationally representative data of Afro-Caribbean (N = 1,418) and African American (N = 3,570) adults from the National Survey of American Life. Results revealed that experiencing discrimination was associated with increased odds of past-year MDD among the total sample. Moreover, for Afro-Caribbeans, but not African Americans, internalized racism was associated with decreased odds of meeting criteria for past-year MDD. We did not find an interaction effect for everyday discrimination by internalized racism, nor an indirect effect of discrimination on risk of past-year MDD through internalized racism. Collectively, our findings suggest a need to investigate other potential mechanisms by which discrimination impacts mental health, and examine further the underlying factors of internalized racism as a potential self-protective strategy. Lastly, our findings point to the need for research that draws attention to the heterogeneity within the U.S. Black population.

Keywords: African Americans, Black Caribbeans, discrimination, internalized racism, mental health

Introduction

Major depressive disorder is one of the most common mental disorders in the United States (US) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011), with an estimated 15.7 million adults (6.7% of the total population) having had a major depressive episode in the past year (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2014). These rates are substantial and of particular concern, given that major depression accounts for the heaviest burden of disease across all mental disorders, including personal (e.g., disability-adjusted life years and years lived with disability; USDHHS, 2014), social, and economic costs (Greenberg & Birnbaum, 2005; Stewart, Ricci, Chee, Hahn, & Morganstein, 2003). Given both the continual rise of depression in the US (Gonzalez, Tarraf, Whitfield, & Vega, 2010) and the major public health implications that it carries, it is not surprising that there has been burgeoning research aiming to uncover its contributing factors.

Social scientists have noted that racial/ethnic minorities experience disproportionately higher levels of certain risk factors, such as racism (Harrell, 2000; Paradies et al., 2015; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), which may put them at increased risk for depression when compared to non-Latino Whites (Alegria, Woo, Takeuchi, & Jackson, 2009; Kessler, Mickelson, & Williams, 1999). Indeed, both the Institute of Medicine’s report “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care” (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003) and the “Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity” (USDHHS, 2001) identified racism as a fundamental contributor of racial/ethnic health disparities, underscoring the need for increased research in this area in an attempt to eliminate disparities for people of color.

Against this backdrop, the present study seeks to identify how different forms of racism (discussed in what follows) may play a role on the risk of past-year major depression between African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US. Although a large body of research exists documenting racism’s association with poor mental health among African Americans (cf. Paradies et al., 2015; Pieterse, Neville, Todd, & Carter, 2012), examining how racism contributes to the mental health of different populations included within the “Black” racial category in the US presents a much-needed opportunity for uncovering potential similarities and differences in exposure to and effects of racism among a large and heterogeneous socially marginalized group. Of equal significance, research on the role of racism on risk of depression among Black populations comes at a critical historic moment when “being Black in America” is being met with high levels of racism, which can have vast implications for a group for whom depression is most severe and debilitating (Williams et al., 2007) and whom already bears the brunt of persistent health disparities (cf. Myers, 2009; Williams & Mohammed, 2009).

Racism and Mental Health

In considering racism’s impact on mental health, we are guided by C. P. Jones’s (2000) theoretical framework for classifying racism, which includes three levels: institutionalized, personally mediated, and internalized. Institutionalized racism encompasses unequal and restricted access to goods and services (e.g., health care facilities, underresourced schools) and opportunities (e.g., confinement into impoverished communities, low-wage labor), all of which can diminish the life chances and health of people of color. Personally mediated racism, one of the most commonly studied forms of racism among psychologists, can be characterized as intentional or unintentional discriminatory acts against people of color through negative interpersonal interactions and prejudice, including being followed around in stores, thought of as less smart than others, called names or insulted, and given poorer services. Internalized racism can be defined as the acceptance of negative attitudes, beliefs, ideologies, and stereotypes perpetuated by the White dominant society as being true about one’s racial group. All three forms of racism can impact the health of people of color, but can also have implications for diminished population-level health (C. P. Jones, 2000). We note that although it is critical that all forms of racism be considered in order to understand their potentially relative, additive, and/or synergistic influence on mental health, we are limited in the present study in that we only have access to measures to assess personally mediated and internalized racism. Nonetheless, we believe that by including at least two forms of racism in a single study, our work is a step forward in understanding the impact of racism on mental health at multiple levels.

A significant body of research demonstrates consistent and robust adverse effects of personally mediated racism (hereinafter referred to as discrimination) on mental health (Paradies et al., 2015). Indeed, the biopsychosocial model of racism (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, 1999) suggests that the psychosocial stress resulting from repeated and cumulative incidents of unfair treatment can trigger a host of emotional and cognitive responses (e.g., negative affect, sadness, rumination), which can heighten risk of psychopathology (Harrell, 2000; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), including onset of depression. In fact, discrimination can convey to individuals that they are different, devalued, and not respected in society (Crocker, Major, & Steele, 1998) and thus may evoke negative emotions (cf. Major, Mendes, & Dovidio, 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that a substantial number of studies have demonstrated robust associations between perceived discrimination and poor mental health, with most outcomes focusing on psychological distress and depressive symptoms (Paradies, 2006). And, a recent meta-analysis of studies published from 1983 to 2013 found that racism had a significant effect on increased risk of diagnosed depression (Paradies et al., 2015).

On the other hand, research on the psychological costs of internalized racism has remained relatively neglected. Yet, internalized racism has been argued to be harmful to a person of color’s mental health, given the injury resulting from it includes reinforcing the superiority of Whites and maintaining a “self-perpetuating cycle of oppression,” while leading to feelings of self-doubt, eroding self-esteem and -worth, and generating helplessness and hopelessness (C. P. Jones, 2000; Speight, 2007). First, internalization of a stigmatized identity may directly impact health-related outcomes. For example, internalized homophobia (Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010), low social status (B. Jackson, Smart Richman, LaBelle, Lempereur, & Twenge, 2014), illness-related stigma (Logie, James, Tharao, & Loufty, 2013), and racism (Taylor & Jackson, 1990) have been associated either with poorer mental health, lower well-being, or health-damaging behaviors. Second, Carter (2007) argues that it is important to understand how discrimination relates to internalized racism, given that being discriminated against may result in self-devaluation and self-blame that may be internalized. Indeed, internalization of negative in-group bias may operate as a conduit by which discrimination impacts health-related outcomes. For example, in a recent study, weight bias internalization partially mediated the association between interpersonal discrimination and eating disturbance among obese persons (Durso, Latner, & Hayashi, 2012); and in a sample of Latino adults, higher levels of everyday discrimination were associated with a perceived lower social status, which in turn was associated with increased levels of psychological distress (Molina, Alegria, & Mahalingam, 2013). Third, internalized racism may also have interactive effects with discrimination. For example, though not focused on mental health, research finds that in African American men, greater perceived discrimination in tandem with endorsing high levels of implicit anti-Black bias, is associated with increased risk of hypertension (Chae, Nuru-Jeter, & Adler, 2012) and shorter leukocyte telomere length (a biological marker of systemic aging; Chae et al., 2014), whereas other studies find that among those reporting no discrimination, endorsing negative racial group attitudes is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Chae, Lincoln, Adler, & Syme, 2010). These studies indicate that when one internalizes in-group racial bias in the presence of feeling discriminated against, threats to both self- and group identity may be embodied as poor health (Chae et al., 2014); and arguably, as poor mental health as well. In sum, evidence from the aforementioned studies suggest that for individuals from stigmatized groups, internalization of negative in-group beliefs, messages, or stereotypes may act as both a mechanism through which discrimination impacts health—including mental health—and also exert its effects in synergistic ways.

Effects of Racism on Mental Health: The Role of Ethnic Subgroup Variation

I consider myself Black because if a White person sees me, that is what they see. They don’t know where I am from and what my culture is, and in some ways that is all that matters … it is not all that matters but it has a very big influence. So, some people make the point that no matter where you think you are from or who you think you are, you look like (a Black person) … and so you will be treated just as unequally as somebody who is African American. (First-generation Trinidadian adult female respondent cited in C. Jones & Erving, 2015, p. 538)

Despite that Afro-Caribbean persons in the US have, in general, higher levels of socioeconomic standing, including education and income (Anderson, 2015), and are also partly comprised of immigrant persons—known protective factors against poor mental health—some studies find that Afro-Caribbean adults report higher prevalence rates of lifetime depression and depressive symptoms when compared to African Americans (Alegria et al., 2009; Cohen, Berment, & Magai, 1997; Williams et al., 2007; Woodward, Taylor, Abelson, & Matusko, 2013). Still, other studies find no between-group differences for past-year diagnosis of depression (Williams et al., 2007; Woodward et al., 2013). These findings may partly reflect the fact that Afro-Caribbeans have some similar racialized experiences to African Americans in U.S. society (Jones & Erving, 2015; Marshall & Rue, 2012; Waters, Kasinitz, & Asad, 2014). For example, as illustrated in the previous quote, some Afro-Caribbean persons in the US may still feel they are treated and perceived similar to African Americans. This is supported by empirical evidence showing no differences in perceived discrimination between these two groups (Marshall & Rue, 2012; Seaton, Caldwell, Sellers, & Jackson, 2008), and that among Afro-Caribbeans, perceiving discrimination is associated with increased feelings of closeness to African Americans (Thornton, Taylor, & Chatters, 2013). Yet, the extent to which and how racialized psychosocial processes impact the mental health of Afro-Caribbeans in the US compared to African Americans remains largely understudied, and thus, poorly understood. Fortunately, an emerging body of research has begun to examine whether subgroup variation in such areas exists within this heterogeneous racial group.

For example, previous research has shown that Afro-Caribbean persons in the US have been relatively more successful (cf. Waters et al., 2014) and typically regarded as “model minorities” compared to African Americans (cf. Thornton et al., 2013). However, the effects of discrimination on mental health appear to impact these two groups in similar ways. In a study of older African American and Afro-Caribbean adults, perceived discrimination was associated with increased depressive symptoms in both groups (Marshall & Rue, 2012), and similar findings have been seen with African American and Afro-Caribbean youth, which show deleterious effects of discrimination on depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in both groups (Seaton, Caldwell, Robert, & Jackson, 2010; Seaton et al., 2008). These studies suggest discrimination may be a normative experience for both groups, despite notable background differences between the two groups.

Less understood, however, is how internalized racism impacts the mental health of both African American and Afro-Caribbean adults. It is well-known that African Americans have had a long history with being negatively stereotyped in U.S. society and misrepresented in the media (e.g., television shows, news programming; Punyanunt-Carter, 2008; Tamborini, Mastro, Chory-Assad, & Huang, 2000). Further, although less is known about stereotypes of Afro-Caribbean persons in the US, one study found that White employers perceived Afro-Caribbean persons in a more positive light (e.g., more ambitious and hardworking, less troublesome) than they did regarding African Americans (Waters, 1999); and in another study (Tormala, 2005 as cited in Deaux et al., 2007), college students endorsed more positive stereotypes about Black immigrants than about African Americans. Differences in stereotypic messages about these two groups may influence the extent to which they are aware of and accept stereotypes about their groups, and how it impacts their mental health. Interestingly, in a study of African American women, internalized racism was only marginally significantly associated with poor mental health (Taylor, Henderson, & Jackson, 1991). Yet in a study of HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women residing in Canada, HIV-related stigma-negative self-image was the only aspect of stigma that was associated with increased depressive symptoms among all of the groups (Logie et al., 2013). Moreover, several studies show that higher levels of internalized racism are associated with stress-associated outcomes, including increased abdominal obesity among Black Caribbean women (Butler, Tull, Chambers, & Taylor, 2002; Tull et al., 1999) and metabolic risk among Caribbean adolescent girls (Chambers et al., 2004). As noted earlier, similar findings have also been seen among African American men (Chae et al., 2012; Chae et al., 2014). As a whole, these findings suggest internalized racism may impact Afro-Caribbeans and African Americans similarly. Yet, limitations of previous studies include a focus on: only Afro-Caribbean women outside of the U.S. context, African American men, physical rather than mental health outcomes, and direct effects of internalized racism but not indirect or moderating effects with discrimination. Further, to our knowledge, no comparative studies in the aforementioned areas exist between African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the U.S. context. In sum, whether ethnic group differences exist in the associations between discrimination, internalized racism, and risk of depression remains an empirical question.

Present Study

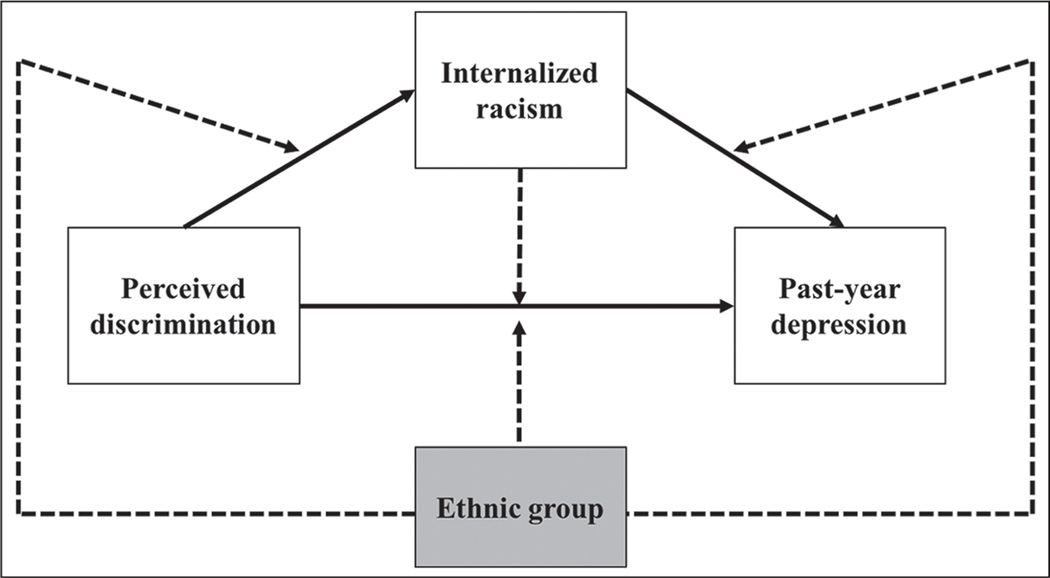

Building upon previous research, the present study focuses on: (a) the direct effects of everyday discrimination and internalized racism on risk of past-year MDD; (b) the synergistic effects between everyday discrimination and internalized racism on risk of past-year MDD; and (c) the indirect association between everyday discrimination and risk of past-year MDD via internalized racism. Further, we explore moderating effects in the said relations by ethnic group membership (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model illustrating the proposed relationships between perceived discrimination, internalized racism, ethnic group, and past-year major depressive disorder. Dashed lines represent moderation.

Based on the aforementioned theoretical and empirical research, we made the following hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that greater frequency of everyday discrimination (H1a) and greater internalized racism (H1b) will be associated with increased risk of meeting criteria for past-year MDD. Second, we hypothesized that internalized racism would moderate the association between discrimination and past-year MDD, such that higher levels of internalized racism would exacerbate the effects of discrimination on past-year MDD (H2). Third, we hypothesized an indirect effect of discrimination on past-year MDD through internalized racism, such that greater frequency of discrimination will be associated with higher levels of internalized racism, which in turn, will be associated with greater odds of meeting criteria for past-year MDD (H3). The limited research on between-group differences in this area prevented us from rendering concrete hypotheses of specific differential effects between African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The present study (N = 4,988) utilized data from the African American (n = 3,570) and Afro-Caribbean (n = 1,418) subsamples of the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), a cross-sectional, nationally representative household survey of noninstitutionalized African American, Afro-Caribbean, and non-Hispanic White adults, ages 18 years or older residing in the US. Although the NSAL was designed to investigate mental disorders among the three referenced groups, for the present study we focus only on the two Black populations, given that not all measures were assessed for the non-Hispanic White subsample. African Americans represent self-identified Black participants who did not identify any ancestral ties to the Caribbean, whereas Afro-Caribbeans represent participants who self-identified as Black and who said they were of West Indian or Caribbean descent. The mean age of the total sample was 42.2 years (SD = 16.2).

An in-depth description of the sample and interview procedures has been presented elsewhere (see Heeringa et al., 2004; J. S. Jackson, Neighbors, Nesse, Trierweiler, & Torres, 2004; J. S. Jackson, Torres, et al., 2004, for more details). We summarize the most pertinent information of the NSAL here. Data collection for the NSAL was conducted between February 2001 and March 2003, primarily via face-to-face interviews by racially concordant, trained lay interviewers in the respondent’s home. Participants were selected via national multistage probability methods. The overall response rate for the NSAL was 72.3%, with the response rate for African Americans at 70.7% and Afro-Caribbeans at 71.5%. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee approved all study procedures. Secondary data analysis of the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) was IRB exempt by the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Measures

Everyday discrimination

Participants rated the frequency with which they encountered unfair treatment on day-to-day basis on the 10-item Everyday Discrimination Scale (EDS; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997), on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = almost every day to 6 = never). Sample items include: “You are treated with less courtesy than other people,” “You are followed in stores,” “You are called names or insulted,” and “You have been threatened or harassed.” Responses to all items were reverse coded and summed, with higher scores representing greater frequency of everyday discrimination, total sample: α = .89; African Americans (AA): α = .89; Afro-Caribbeans (AC): α = .89.

Internalized racism

Participants were queried with:

Many different words have been used to describe [respective racial/ethnic group: Black people/Black Americans/Afro-Caribbean] people in general. Some of these words describe good points and some of these words describe bad points. How true do you think each of these words is in describing [respective racial/ethnic group: Black people/Black Americans/Afro-Caribbean] people? How true do you think it is, that most [respective racial/ethnic group: Black people/Black Americans/Afro-Caribbean] people are: intelligent, lazy, hardworking, give up easily, proud of themselves, and violent?

Participants rated the extent to which they agreed with each item. Agreement on each item was rated on a 4-point scale (1 = very true to 4 = not true at all). Responses to statements for intelligent, hardworking, and proud of themselves were reverse-coded. All items were then summed, with higher scores reflecting greater endorsement of negative group stereotypes (total sample α = .70; AA: α = .65; AC: α = .74).

Past-year major depressive disorder (MDD)

Past-year MDD was assessed using the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI). The WMH-CIDI is a fully structured psychiatric diagnostic instrument that is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994). The WMH-CIDI can be used cross-culturally and can be administered by nonclinically trained lay people (Kessler & Üstün, 2004). The WMH-CIDI classifies individuals as either meeting DSM-IV criteria (1) for past-year MDD or not (0). Diagnostic criteria for MDD requires depressed mood or a loss of pleasure or interest that represents a change from before in daily activities for at least 2 weeks and a minimum of five out of nine symptoms (e.g., depressed mood most of the day; diminished interest or pleasure in all or most activities; significant unintentional weight loss or gain; insomnia or sleeping too much; agitation or psychomotor retardation noticed by others; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt; diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness; and recurrent thoughts of death) that cause clinically significant impaired functioning in everyday activities (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994).

Covariates

We included the following sociodemographic variables in our analyses: age (in years), sex (male [reference group] or female), educational attainment (0–11 years [reference group], 12 years, 13–15 years, and 16 years or more), household income ($0–14,999 [reference group]; $15,000–34,999; $35,000–74,999; $75,000 and over), marital status (married/cohabitating [reference group], divorced/separated/widowed, or never married), work status (employed [reference group] or unemployed), nativity status (U.S.-born [reference group] or foreign-born), and years in the US (0 to less than 5 years [reference group] or 5 or more years), given that epidemiologic work, including research with the NSAL, has shown them to be correlates of mental health disorders and depressive symptomatology (cf. Alegria et al., 2009, for a review of ethnic and racial group-specific considerations regarding correlates of mental health disorders). Moreover, given differences across sociodemographic characteristics among African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans, it is important that we accounted for these differences in our analyses. We also controlled for social desirability bias using the 10-item Crowne– Marlowe Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960) due to the use of self-report measures that include sensitive topics (e.g., discrimination, internalized racism). For each social desirability item (e.g., “I have always told the truth,” “I have never been bored”), participants provided a value of 0 (false) or 1 (true). All items were summed, with higher scores reflecting greater social desirability bias.

Data Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics were conducted to examine between-group differences on sociodemographic and main study variables. We also examined the correlations between the main study variables by racial/ethnic group.

Regarding our main analyses, first we conducted weighted multivariable logistic regressions to model the odds of meeting DSM-IV criteria for past-year MDD. These analyses included first examining the main (direct) effects of everyday discrimination and internalized racism on past-year MDD (Model 1). In Model 2, we tested for the interactive effect of everyday discrimination and internalized racism on past-year MDD. Additionally, as a second step, we tested whether group membership moderated the associations between everyday discrimination and internalized racism and past-year MDD, respectively (Model 3). To reduce issues with multicollinearity, we mean-centered continuous variables included in interaction terms (Aiken & West, 1991). To better understand significant interactions, we used coefficients to calculate predicted probabilities of MDD, and graphed simple slopes for each conditional effect at one standard deviation above, at the mean, and below the grand mean of the predictor variable (Aiken & West, 1991). All of these analyses were adjusted for the aforementioned covariates and were conducted with Stata 13. Next, to test for the indirect effect of discrimination on past-year MDD through internalized racism, we conducted weighted path analysis using Mplus Version 7.3. Indirect paths were fitted using the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) with 500 Montecarlo integrations in order to obtain the odds ratio for the dichotomous outcome variable and robust beta estimates for indirect effects along with confidence intervals (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). All of our analyses (excluding correlations, which are unweighted) accounted for the NSAL complex sample design and differential nonresponse by incorporating weighting, clustering, and stratification variables. This allowed for estimation of standard errors in the presence of stratification and clustering, and to obtain estimates that are representative and generalize back to the larger population of African American and Afro-Caribbean persons in the US.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 summarizes the weighted distribution of selected sociodemographic characteristics for the total sample and by racial/ethnic group. Significant group differences were observed for all sociodemographic variables except for age.

Table 1.

Weighted means, standard deviations, and proportions of selected sociodemographic characteristics for the total sample and by race/ethnic subgroup.

| Characteristic | Race/ethnic group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample N = 4,988 |

African American (n = 3,570) |

Afro-Caribbean (n = 1,418) |

Design-based F test or χ2 |

p-valuea | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 42.24 (16.22) | 42.33 (18.17) | 40.84 (35.45) | (1, 54) = 1.69 | 0.198 |

| Range | 18–94 | 18–93 | 18–94 | ||

| Social desirability, mean (SD) | 2.01 (1.78) | 2.03 (2.01) | 1.86 (4.71) | (1, 54) = 4.32 | 0.042 |

| Range | 0–10 | 0–10 | 0–10 | ||

| Gender | (1, 54) = 4.95 | 0.030 | |||

| Male | 3,163 (55.57) | 2,299 (55.97) | 864 (49.02) | ||

| Female | 1,825 (44.43) | 1,271 (44.03) | 554 (50.98) | ||

| Marital status, n (%) | (1.69, 91.03) = | 0.001 | |||

| Married/cohabitating | 1,828 (42.21) | 1,222 (41.65) | 606 (51.13) | 8.56 | |

| D/S/W | 1,497 (26.32) | 1,164 (26.77) | 333 (18.99) | ||

| Never married | 1,655 (31.48) | 1,176 (31.57) | 479 (29.88) | ||

| Education, n (%) | (1.98, 106.96) | 0.003 | |||

| 0–11 years | 1,182 (23.9) | 920 (24.19) | 262 (19.20) | = 6.21 | |

| 12 years | 1,778 (37.39) | 1,362 (37.86) | 416 (29.77) | ||

| 13–15 years | 1,193 (24.09) | 809 (23.83) | 384 (28.33) | ||

| ≥16 years | 835 (14.62) | 479 (14.12) | 356 (22.69) | ||

| Household income ($), n (%) | (2.63, 142.16) | 0.003 | |||

| 0–14,999 | 1,282 (24.06) | 1,054 (24.70) | 228 (13.81) | = 5.31 | |

| 15,000–34,999 | 1,795 (33.83) | 1,282 (33.88) | 513 (33.11) | ||

| 35,000–74,999 | 1,459 (31.59) | 972 (31.3) | 487 (36.42) | ||

| 75,000 and over | 452 (10.51) | 262 (10.13) | 190 (16.66) | ||

| Work status, n (%) | (1, 54) = 26.83 | 0.000 | |||

| Employed | 3,386 (67.38) | 2,334 (66.83) | 1052 (76.18) | ||

| Unemployed | 1,593 (32.62) | 1,227 (33.17) | 366 (23.82) | ||

| Nativity status | (1, 54) = | 0.000 | |||

| U.S.-born | 3,830 (93.72) | 3,464 (97.69) | 366 (30.15) | 1108.93 | |

| Foreign-born | 1,115 (6.28) | 64 (2.31) | 1051 (69.85) | ||

| Years in the US | (1, 54) = 76.42 | 0.000 | |||

| 0 to less than 5 years | 135 (1.27) | 19 (.77) | 116 (9.30) | ||

| 5 or more years | 4,769 (98.73) | 3,474 (99.23) | 1295 (90.70) | ||

Note. D/S/W= Divorced/separated/or widowed.

Rao-Scott statistics for the Pearson chi-square test for contingency tables were computed for categorical variables and design-based adjusted Wald-tests of differences were computed for continuous variables for race/ethnicity.

Overall, there were low levels of reported everyday discrimination in the total sample (M = 12.72; SD = 5.38; range = 1–60), with Afro-Caribbeans (M = 12.56; SD = 5.33) reporting higher levels of everyday discrimination than African Americans (M = 12.73; SD = 5.38), F(1, 4943) = 4.52, p = .034. Moreover, results showed moderate levels of internalized racism among the total sample (M = 10.77; SD = 2.98; range = 1–16), with African Americans (M = 10.89; SD = 2.95) reporting more internalized racism than Afro-Caribbeans (M = 8.79; SD = 2.74), F(1, 4922) = 542.52, p = .000. Finally, of the total sample, 6.76 % met DSM-IV criteria for past-year MDD; however, the proportion of respondents who met criteria for past-year MDD did not differ between African Americans (6.76%) and Afro-Caribbeans (6.70%), χ2(1, 54) = 0.428, p = .516.

Correlations between main study variables for the total sample showed that everyday discrimination was positively associated with internalized racism (r = .085, p < .001) and past-year MDD (r = .119, p < .001), and internalized racism was positively associated with meeting criteria for past-year MDD (r = .032, p < .027). Table 2 shows correlations among everyday discrimination, internalized racism, and past-year MDD for African American and Afro-Caribbean respondents.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of main study variables for African American and Afro-Caribbean respondents.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Everyday discrimination | – | 0.101*** | 0.124*** |

| 2. Internalized racism | 0.015 | – | 0.043** |

| 3. Past-year major depressive disorder | 0.101*** | −0.027 | – |

Note. Correlations above line = African American sample. Correlations below line = Afro-Caribbean sample. Pearson’s correlations were conducted for continuous by continuous variables. Point biserial correlations were conducted for binary by continuous variables.

p < .01.

p < .001.

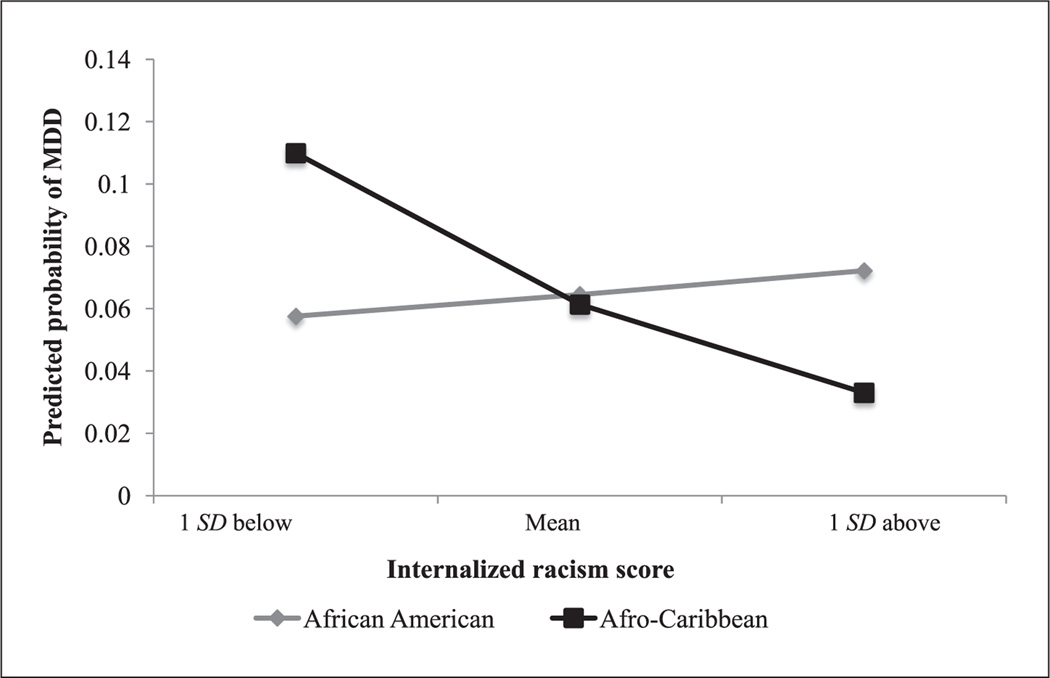

Direct (Main) and Moderating Effects

Table 3 shows that in Model 1, where we only included main effects to test for Hypotheses 1a and 1b, we found that higher frequency of everyday discrimination was associated with increased odds of meeting DSM-IV criteria for past-year MDD (OR = 1.06; 95% CI [1.04, 1.08]). However, no statistically significant association was noted for internalized racism. When we included the Everyday Discrimination x Internalized Racism interaction to test for Hypothesis 2, results in Model 2 revealed that the effect for everyday discrimination remained significant, but there was no statistically significant two-way interaction present, F(1, 54) = 0.04, p = .834. Lastly, when testing whether the direct associations between everyday discrimination and internalized racism, respectively, on past-year MDD were moderated by group membership (Model 3), we found a significant group moderating effect for the association between internalized racism and past-year MDD (OR = .76; 95% CI [0.65, 0.90]), F(1, 54) = 20.96, p = .002, with Afro-Caribbean persons being at decreased risk of past-year MDD in the context of high levels of internalized racism compared to their African American counterparts (see Figure 2). The Everyday Discrimination x Group Membership interaction was nonsignificant, F(1, 54) = 0.33, p = .571. All analyses were adjusted for covariates (see Appendix A for estimates of covariates). As a sensitivity check, we examined whether a three-way interaction (Everyday Discrimination × Internalized Racism × Group Membership) was present; we did not find this to be the case, F(1, 54) = 1.41, p = .240.

Table 3.

Weighted logistic regressions of past-year major depressive disorder (MDD) among total sample.

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Direct (main) effects | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| African American | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Afro-Caribbean | 1.58 [0.74, 3.35] | 1.58 [0.74, 3.35] | 0.81 [0.34, 1.92] |

| Everyday discrimination (ED) | 1.06 [1.04, 1.08]*** | 1.06 [1.04, 1.08]*** | 1.06 [1.04, 1.08]*** |

| Internalized racism (IR) | 1.03 [0.97, 1.10] | 1.02 [0.91, 1.14] | 1.03 [0.92, 1.16] |

| Two-way interactions: Step 1 | |||

| ED x IR | 1.00 [0.99, 1.01] | 1.00 [1.00, 1.01] | |

| Two-way interactions: Step 2 | |||

| ED x Race/Ethnicity | 1.01 [0.98, 1.04] | ||

| IR x Race/Ethnicity | 0.76 [0.65, 0.90]** |

Note. All models adjusted for covariates. OR = Odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval; Ref = Reference group.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Adjusted predicted probability of past-year major depressive disorder (MDD) as a function of internalized racism and race/ethnicity.

Path Analysis of Indirect Effects

Table 4 shows results for indirect effects (and the direct effects by total sample and subgroup). Our analyses revealed that everyday discrimination was not indirectly associated with increased risk of past-year MDD via internalized racism neither among the total sample (p = .349), for African Americans (p = .226), or among Afro-Caribbean respondents (p = .377). Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, we ran an additional path model where we reversed the order of our predictor and intervening variables to test for the indirect effect of internalized racism on past-year MDD via everyday discrimination. We then tested the fit of our hypothesized mediational path to the alternative mediational model by comparing Bayesian information criterion (BIC) fit index values (Schwarz, 1978), which can be used to compare nonnested models with dichotomous outcomes (Kass & Raftery, 1995; Raftery, 1995). When the BIC value between two models has a difference of 10 or more, the model with a lower BIC value is said to fit best to the data (Raftery, 1993). Results showed that the hypothesized model fit best to the data, even though the indirect path was nonsignificant, whereas the indirect path for the alternative mediational model was significant for the total sample and among African Americans (see Table 4). All analyses were adjusted for covariates (see Appendices B and C for estimates of covariates for hypothesized and alternative path models, respectively).

Table 4.

Weighted path estimates for total sample and by race/ethnic subgroup.

| Specific paths | Hypothesized path model |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample |

African American |

Afro-Caribbean |

|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Everyday discrimination (ED)MDD | 1.06 [1.04, 1.07]*** | 1.06 [1.04, 1.07]*** | 1.07 [1.04, 1.10]*** |

| Internalized racism (IR)MDD | 1.03 [0.98, 1.08] | 1.04 [0.99, 1.10] | 0.75 [0.67, 0.85]*** |

| ED➔IRa | 0.03 [0.02, 0.04]*** | 0.03 [0.02, 0.04]*** | 0.02 [−0.02, 0.07] |

| ED➔IR➔MDDa | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | −0.01 [−0.02, 0.01] |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 25,956.58 | 18,424.18 | 69,68.71 |

| Alternative path model | |||

| Specific paths | Total sample | African American | Afro-Caribbean |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Internalized racism (IR)➔MDD | 1.03 [0.98, 1.09] | 1.04 [0.99, 1.10] | 0.74 [0.66, 0.84]** |

| Everyday discrimination (ED)➔MDD | 1.06 [1.04, 1.07]*** | 1.06 [1.04, 1.07]*** | 1.05 [1.02, 1.08]*** |

| IR➔EDa | 0.27 [0.18, 0.36]*** | 0.27 [0.02, 0.36]*** | 0.31 [−0.20, 0.82] |

| IR➔ED➔MDDa | 0.01 [0.01, 0.02]*** | 0.02 [0.01, 0.02]*** | 0.02 [−0.01, 0.04] |

| Bayesian information criterion (BIC) | 36,390.98 | 25,897.11 | 10,662.33 |

Note. ED = Everyday discrimination; IR = Internalized racism; MDD = Past-year major depressive disorder.

Unstandardized beta estimate.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Summary of Results

Overall, our results showed partial support for our first hypotheses: everyday discrimination, but not internalized racism, was associated with increased risk of DSM-IV criteria of past-year MDD, after adjustment for a number of covariates. Further, our second hypothesis that internalized racism would moderate the association between everyday discrimination and past-year MDD was not supported. Moreover, our third hypothesis that everyday discrimination would be associated with increased risk of past-year MDD via greater internalized racism was also not supported. Lastly, our exploratory analyses testing for moderating effects by ethnic group membership showed support for between-group differences in the association between internalized racism and risk of past-year MDD. We did not find any support for between-group differences for the indirect effects.

Discussion

Direct Effects of Everyday Discrimination and Internalized Racism

The first goal of our study was to investigate whether everyday discrimination and internalized racism were independently associated with increased risk of past-year MDD for the total sample. We found partial support for our hypothesis. Everyday discrimination—a form of modern racism that is subtle and ambiguous (Williams et al., 1997)—was associated with increased risk of past-year MDD. This is consistent with theoretical formulations of interpersonally mediated racism as a psychosocial stressor that increases risk of depression for people of color (Clark et al., 1999; C. P. Jones, 2000), given it may engender feelings of demoralization and devaluation. More striking is that despite the rather low levels of everyday discrimination noted among the total sample, our results show how pervasive the effects of discrimination can be. Conversely, internalized racism was not associated with risk of past-year MDD. One potential explanation for this nonsignificant finding could be due to methodological differences, including discrepancies in measurement of internalized racism, outcome measured, and samples across previous studies and ours. Studies that find a significant association for internalized racism all focused on physical health outcomes (Chae et al., 2010; Tull et al., 1999) or health-damaging behaviors (Taylor & Jackson, 1990); and studies focused on mental health outcomes found either a marginally significant association for depressive symptoms among African American women (Taylor et al., 1991) or nonsignificant associations for anxiety and depression among Afro-Caribbean women (Tull et al., 1999). An alternative explanation could be that endorsing negative stereotypes about one’s group could be a proxy for knowledge about stereotypes of one’s group, and not necessarily acceptance of them as part of her/himself (Ritsher & Phelan, 2004). Thus, when endorsing negative stereotypes about one’s group, individuals may be more likely to engage in “system blaming” such as making attributions to negative stereotypes to broader external factors in order to lessen threat to their identity and preserve their self-esteem (Crocker & Major, 1989).

Moderating Effects of Internalized Racism

Results from our moderation analyses provide additional insight into the previous findings. That is, our hypothesis that internalized racism would moderate the association between everyday discrimination and risk of MDD was not supported. These findings are in contrast to the significant moderating effects of internalized racism that Chae and colleagues (Chae et al., 2012; Chae et al., 2014) found. However, it should be noted that this effect was present when measured implicitly and the outcomes were not mental health ones, which could have accounted for our differential findings. However, we found that among Afro-Caribbean respondents, but not African Americans, higher levels of internalized racism were associated with decreased risk of past-year MDD. Although our findings seem counterintuitive, they are somewhat in line with previous research. It may be that for Afro-Caribbean adults, endorsing higher levels of negative in-group bias serves a self-protective strategy—what Burkley and Blanton (2008) call functional internalization, and which may lead to positive consequences. For example, one study found that women who failed a math test but were reminded of negative stereotypes tied to women and math performance rated their self-esteem higher than those who were not reminded of the negative stereotypes; and endorsement of these negative stereotypes were greater among women with higher levels of self-esteem compared to those with lower self-esteem (Burkley & Blanton, 2008). Therefore, these findings together with theoretical research on the self-protective properties of stigma (Crocker & Major, 1989) suggest that endorsement of negative stereotypes may not always lead to internalization, but rather may protect one’s self-concept under certain conditions, which in turn, may help decrease risk of poor mental health. At the same time, it may be that negative stereotypes about one’s group may be commonplace for African Americans, such that they do not affect them in either a positive or negative way. Perhaps the findings are partly accounted for by greater exposure to racial socialization messages related to preparation for bias and what it means to be “Black in America.” This may shield African Americans from internalizing any kind of stigma they experience or are attuned to, which is in line with findings that show that in the context of marginalization, racial socialization messages tied to preparing for discrimination are associated with decreased levels of depressive symptoms among African American young adults (Bynum, Burton, & Best, 2007). It may be that a similar process is taking place in the context of internalized racism.

On the other hand, we did not find that group membership moderated the association between everyday discrimination and risk of past-year MDD, which is consistent with previous research that finds no ethnic group differences in the way discrimination impacts the mental health of Afro-Caribbeans and African Americans (Marshall & Rue, 2012; Seaton et al., 2010; Seaton et al., 2008). Again, it appears that interpersonally mediated racism (e.g., everyday discrimination), which can be attributionally ambiguous and thus more cognitively burdensome and psychologically taxing, is a ubiquitous and consistent contributor to poor mental health for people of color (Paradies et al., 2015).

Internalized Racism as a Potential Mechanism

It was surprising that our study provided no evidence to support the hypothesis that everyday discrimination would be indirectly associated with increased risk of depression via internalized racism—suggesting other potential mediators. First, this could be partly due to the fact that everyday discrimination is not associated with internalized racism among Afro-Caribbeans and that internalized racism was not associated with risk of MDD for African Americans. Alternatively, previous research with African American adults finds that anticipatory vigilance—a coping strategy that is characterized by monitoring and modifying one’s behavior in an attempt to protect the self from anticipated racist events (Clark, Benkert, & Flack, 2006)—mediated the association between everyday discrimination and stress, and in turn, depressive symptoms (Himmelstein, Young, Sanchez, & Jackson, 2014). Given that racism-related vigilance has been argued to be a common practice among individuals who report experiencing discrimination (Hicken, Lee, Ailshire, Burgard, & Williams, 2013; Williams & Mohammed, 2009), perhaps this maladaptive strategy is a more common response to discrimination than internalized racism, given that vigilance may help to foster a greater sense of control and feelings of autonomy, irrespective of its negative health consequences (Clark et al., 2006; Hicken et al., 2013; Himmelstein et al., 2014). Thus, it will be important to consider the possible range of emotional, behavioral, and cognitive strategies that individuals develop as a response to chronic exposure to discrimination in order to more fully understand health disparities (cf. Major et al., 2013).

Interestingly, we note that when we tested the alternative model where the direction between everyday discrimination and internalized racism were reversed, we found support for partial mediation, such that higher levels of internalized racism were associated with increased levels of everyday discrimination, and in turn, this was associated with increased risk of MDD among the total sample and for African Americans. Further, all other paths in the model remained significant and in the same direction. Although it is plausible that the direction of everyday discrimination and internalized racism are reversed, we should exercise caution in evaluating the models because our analyses are based on cross-sectional data and we must take into account the theoretical meaningfulness of the relationships between the variables (Byrne, 2012). Indeed, the fit of the alternative model was not better than the hypothesized path model that was tested and that did not reach statistical significance for the indirect effect, but was in line with theory and empirical research.

Limitations and Future Directions

As with any other study, there are key limitations that warrant attention. First, data from the NSAL are cross-sectional, which limits our ability to infer causation or establish the temporal ordering of our variables. For example, it may be that individuals who are depressed are more likely to report higher frequency of discrimination or see themselves in a negative light. However, although this could certainly be the case (cf. Cox, Abramson, Devine, & Hollon, 2012), longitudinal work suggests that within the African American population, discrimination increases the risk of depression and not the other way around (Gee & Walsemann, 2009; Schulz at al., 2006). Further, given that we found that the alternative model where the everyday discrimination– internalized racism association was significant when the variables were reversed, the findings suggest that longitudinal and experimental research is needed to test and better understand the directionality of variables in the model.

Second, our measures were all self-report, which may be subject to participant bias. However, controlling for social desirability helps to minimize this concern. Nonetheless, future studies should aim to incorporate both explicit and implicit measures of discrimination and own-group stereotype endorsement, given that explicit beliefs about one’s group generally operate independently of implicit beliefs (Devine, 1989; Krieger et al., 2010). We should note that the internal consistency of the internalized racism measure was rather low for African Americans, which may have resulted in nonsignificant findings. Future studies will do well by assessing the multidimensionality and psychometric validity of different measures of internalized racism.

Third, our study is limited due to our inability to fully understand the different mechanisms through which interpersonally mediated racism impacts mental health, and whether other factors that may be relevant for each group are moderators (e.g., racial/ethnic socialization messages and practices, racial/ethnic identity, resistance strategies) of the association between everyday discrimination and risk of depression. There are arguably many ways in which marginalized groups cope with stigma and discriminatory experiences. Bearing this in mind, future work should target resilience factors that may help us understand better how individuals weather discriminatory experiences. We also point to the fact that a large proportion (~70%) of the Afro-Caribbean sample was foreign-born. Despite controlling for nativity status and exposure to the US via years in the US, these are only proxies to migratory experiences such as acculturative stress and cultural dissonance (Lacey et al., 2015) as well as other identity-relevant constructs such as national identity—all of which may be associated with discrimination, internalized racism, and mental health.

Fourth, some scholars (cf. Govia, 2009) have argued for the importance of first understanding how these psychosocial processes might work within the Afro-Caribbean population. Indeed, it is important to note that the term “Afro-Caribbean” is a rather amorphous one that encompasses individuals across a broad range of religious, linguistic, racial, immigration, and geographic regional differences (Waters et al., 2014) which makes broad generalizations about this group a limitation of the study. Thus, just as the Black population does not form a monolithic entity, the Afro-Caribbean group does not either. Aside from concerns regarding testing for within-group differences as being beyond the scope of this study, it should also be noted that some of the Afro-Caribbean groups were too small to conduct additional analyses. Nonetheless, future research should aim to at least collapse some groups that may share similar characteristics and attempt to disentangle further the findings for Afro-Caribbean respondents.

Lastly, despite some similar racialized experiences between African American and Afro-Caribbean persons, there are also some notable differences between these two groups. This speaks to the importance of first paying attention to potential qualitative differences between these two groups in how they conceptualize discrimination and internalize racism. Qualitative data may help provide a more nuanced and contextualized understanding of these constructs and the dynamic processes related to stigma and intergroup processes across these two groups, which could then be tested more explicitly in quantitative studies.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding the aforementioned limitations, our study had several strengths that we believe contribute greatly to the literature on intergroup processes and health disparities. First, our study included a nationally representative sample of African American and Afro-Caribbean adults in the US, which affords generalizations back to the larger population of these groups. Prior studies with these populations have largely limited their focus on one racial/ethnic group, one gender (e.g., African American men; Afro-Caribbean women), or samples outside of the US, whereas our comparative study in the US included both men and women as part of the sample. Importantly, we incorporated two measures of racism and examined mediating and moderating effects in our study. Together, our innovative analyses highlight similarities and differences between African American and Afro-Caribbean persons in the US.

Overall, our findings have several implications. First, demographic trends highlight the growing presence of Afro-Caribbeans in the US (Anderson, 2015), which points to the need for increased research on such an understudied social group that evidences health disparities in a number of areas, including depression (Alegria et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2007). Moreover, given that our study focused on risk of depression because of its clinical significance, our findings suggest that interventions aimed at reducing poor mental health among people of color should consider the role of coping with discrimination. For example, in the context of uncontrollable and ambiguous experiences such as everyday discrimination, it may be useful to consider the role of “shift-and-persist” strategies, which include reframing appraisals to stressful situations (through emotion regulation) along with persisting through life with optimism and meaning (Chen & Miller, 2012). On the other hand, as others have suggested (Ritsher & Phelan, 2004), it remains critical to combat discrimination within society and to study the way it is internalized among stigmatized individuals. At the same time, given our finding suggesting endorsing negative stereotypes may be self-protective, understanding the underlying elements that facilitate this will be critical for finding effective solutions that recognize capacities within individuals and communities that empower them to challenge and resist rather than accept negative dominant ideologies and beliefs about one’s group and move to collective action. Moreover, given that we focused on individual-level racism, we may be better able to intervene on personally mediated and internalized racism by intervening at the institutional level, including addressing structural barriers such as unequal access to opportunities and resources (C. P. Jones, 2000, 2003). Lastly, as argued by C. P. Jones (2003):

The scientific investigation of the role of racism in contributing to health disparities is not simply an academic exercise of establishing a causal relationship or decreasing the amount of unexplained variance in our statistical models. This work will be of value when it identifies the pathways and structural mechanisms by which racism has its impacts. Once that has been accomplished, it will be a matter of political will to target these pathways and mechanisms for intervention. (p. 9)

Finally, decontextualized portrayals of Black persons in the US may conceal important similarities as well as variations across cultural, demographic, geographic, and social dimensions that may be associated with divergent experiences, psychosocial adaptation, and mental health profiles among Black ethnic groups. The deep diversity that is present among this segment of our population merits further study in research on psychosocial processes and health disparities. Such research may help us better understand how to prevent, reduce, and ultimately eliminate disparities in this heterogeneous and growing population in the US.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Kristine M. Molina was partially supported by the K12 Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Career Development Award (Eunice Shriver Kennedy National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant # K12HD055892).

Appendix 1. Weighted estimates for covariates from Table 3 weighted logistic regressions predicting past-year depressive disorder (MDD) among total sample

| Covariates | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age, years | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99]* | 0.98 [0.97, 1.00]* | 0.98 [0.97, 1.00]* |

| Social desirability | 0.87 [0.79, 0.96]*** | 0.87 [0.79, 0.96]*** | 0.87 [0.79, 0.96]*** |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.89 [1.37, 2.62]*** | 1.89 [1.37, 2.62]*** | 1.87 [1.34, 2.61]*** |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| D/S/W | 2.26 [1.27, 4.05]*** | 2.27 [1.27, 4.05]*** | 2.28 [1.27, 4.08]*** |

| Never married | 1.62 [1.02, 2.57]* | 1.62 [1.02, 2.56]* | 1.64 [1.04, 2.60]* |

| Education | |||

| 0–11 year | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 12 years | 0.62 [0.40, 0.97]* | 0.62 [0.40, 0.97]* | 0.62 [0.40, 0.97]* |

| 13–15 years | 0.63 [0.39, 1.05] | 0.63 [0.38, 1.05] | 0.64 [0.38, 1.06] |

| ≥ 16 years | 0.79 [0.43, 1.43] | 0.78 [0.43, 1.42] | 0.79 [0.43, 1.43] |

| Household income | |||

| $0–14,999 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $15,000–34,999 | 0.99 [0.68, 1.45] | 0.99 [0.68, 1.45] | 0.98 [0.68, 1.43] |

| $35,000–74,999 | 1.17 [0.71, 1.93] | 1.18 [0.72, 1.93] | 1.16 [0.71, 1.91] |

| $75,000 and over | 1.34 [0.58, 3.14] | 1.34 [0.58, 3.14] | 1.29 [0.54, 3.07] |

| Work status | |||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Unemployed | 1.29 [0.92, 1.81] | 1.29 [0.92, 1.81] | 1.29 [0.92, 1.81] |

| Nativity status | |||

| U.S.-born | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Foreign-born | 0.53 [0.19, 1.53] | 0.53 [0.19, 1.52] | 0.47 [0.15, 1.51] |

| Years in the US | |||

| 0 to less than 5 years | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 5 or more years | 0.30 [0.09, 1.00]+ | 0.30 [0.09, 1.00]* | 0.27 [0.08, 0.97]* |

Note. D/S/W= Divorced/separated/or widowed; Ref = Reference group.

p = .05.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Appendix 2. Weighted estimates of covariates in hypothesized path model for past-year MDD from Table 4 for total sample and by race/ethnic subgroup

| Covariates | Total sample |

African American |

Afro-Caribbean |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Race/ethnic group | – | – | |

| African American | Ref | – | – |

| Afro-Caribbean | 1.71 [0.98, 2.99] | ||

| Age, years | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99]* | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99]* | 1.01 [0.98, 1.05] |

| Social desirability | 0.87 [0.80, 0.94]** | 0.87 [0.80, 0.94]** | 0.91 [0.74, .1.11] |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.88 [1.45, 2.45]*** | 2.03 [1.54, 2.68]*** | 0.67 [0.30, 1.53] |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| D/S/W | 2.24 [1.39, 3.60]** | 2.34 [1.42, 3.86]** | 1.11 [0.38, 3.26] |

| Never married | 1.66 [1.15, 2.41]* | 1.64 [1.10, 2.44]* | 2.91 [1.60, 5.28]** |

| Education | |||

| 0–11 year | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 12 years | 0.62 [0.43, 0.89]* | 0.63 [0.44, 0.92]* | 0.54 [0.18, 1.66] |

| 13–15 years | 0.62 [0.41, 0.94] | 0.64 [0.41, 0.99] | 0.87 [0.35, 2.13] |

| ≥ 16 years | 0.77 [0.47, 1.26] | 0.77 [0.45, 1.29] | 1.12 [0.35, 3.54] |

| Household income | |||

| $0–14,999 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $15,000–34,999 | 0.99 [0.73, 1.34] | 0.95 [0.69, 1.29] | 1.29 [0.43, 3.84] |

| $35,000–74,999 | 1.17 [0.78, 1.75] | 1.25 [0.82, 1.91] | 0.29 [0.15, 0.58]** |

| $75,000 and over | 1.33 [0.67, 2.67] | 1.41 [0.67, 2.99] | 0.27 [0.09, 0.84] |

| Work status | |||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Unemployed | 1.28 [0.97, 1.70] | 1.38 [1.03, 1.84] | 0.44 [0.25, 0.78]** |

| Nativity status | |||

| U.S.-born | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Foreign-born | 0.44 [0.17, 1.09] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.34 [0.14, 0.82]* |

| Years in the U.S. | |||

| 0 to less than 5 years | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 5 or more years | 0.20 [0.07, 0.56]* | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.51 [0.17, 1.56] |

Note. D/S/W= Divorced/separated/or widowed; Ref = Reference group.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Appendix 3. Weighted estimates of covariates in alternative path model for past-year MDD from Table 4 for total sample and by race/ethnic subgroup

| Covariates | Total sample |

African American |

Afro-Caribbean |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Race/ethnic group | |||

| African American | Ref | – | – |

| Afro-Caribbean | 1.58 [0.85, 2.93] | – | – |

| Age, years | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99]* | 0.98 [0.97, 0.99]* | 1.01 [0.98, 1.05] |

| Social desirability | 0.87 [0.81, 0.94]** | 0.87 [0.80, 0.94]** | 0.92 [0.74, .1.14] |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | |||

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabitating | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| D/S/W | 2.26 [1.41, 3.65]** | 2.36 [1.43, 3.89]** | 1.03 [0.37, 2.85] |

| Never married | 1.62 [1.11, 2.36]* | 1.62 [1.08, 2.41]* | 2.16 [1.13, 4.13] |

| Education | |||

| 0–11 year | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 12 years | 0.62 [0.43, 0.89]* | 0.64 [0.44, 0.93]* | 0.38 [0.13, 1.14] |

| 13–15 years | 0.63 [0.42, 0.96] | 0.65 [0.42, 1.00] | 0.81 [0.29, 2.20] |

| ≥ 16 years | 0.79 [0.48, 1.28] | 0.78 [0.46, 1.31] | 1.10 [0.35, 3.48] |

| Household income | |||

| $0–14,999 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| $15,000–34,999 | 0.99 [0.73, 1.35] | 0.95 [0.70, 1.31] | 1.10 [0.36, 3.26] |

| $35,000–74,999 | 1.18 [0.78, 1.77] | 1.26 [0.82, 1.92] | 0.26 [0.13, 0.52]** |

| $75,000 and over | 1.35 [0.67, 2.67] | 1.43 [0.67, 3.02] | 0.22 [0.07, 0.67]* |

| Work status | |||

| Employed | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Unemployed | 1.29 [0.98, 1.71] | 1.37 [1.02, 1.83] | 0.53 [0.36, 0.78]** |

| Nativity status | |||

| U.S.-born | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Foreign-born | 0.53 [0.22, 1.27] | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 0.34 [0.15, 0.78]* |

| Years in the US | |||

| 0 to less than 5 years | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 5 or more years | 0.30 [0.11, 0.81]* | 0.00 [0.00, 0.00] | 1.40 [0.47, 4.14] |

Note. D/S/W= Divorced/separated/or widowed; Ref = Reference group.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Alegria M, Woo M, Takeuchi D, Jackson J. Ethnic and racial group-specific considerations. In: Ruiz P, Primm A, editors. Disparities in psychiatric care: Clinical and cross-cultural perspectives. Bethesda, MD: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2009. pp. 306–318. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. A rising share of the U.S. Black population is foreign-born. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2015. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/04/09/a-rising-share-of-the-u-s-black-population-is-foreign-born/ [Google Scholar]

- Burkley M, Blanton H. Endorsing a negative in-group stereotype as a self-protective strategy: Sacrificing the group to save the self. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2008;44:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Butler C, Tull ES, Chambers EC, Taylor J. Internalized racism, body fat distribution, and abnormal fasting glucose among African-Caribbean women in Dominica, West Indies. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2002;94:143–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum MS, Burton ET, Best C. Racism experiences and psychological functioning in African American freshmen: Is racial socialization a buffer? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:64–71. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 2nd. New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT. Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35:13–105. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental illness surveillance among adults in the United States (MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 60) 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6003a1.htm. [PubMed]

- Chae DH, Lincoln KD, Adler NE, Syme SL. Do experiences of racial discrimination predict cardiovascular disease among African American men? The moderating role of internalized negative racial group attitudes. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:1182–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Adler NE. Implicit racial bias as a moderator of the association between racial discrimination and hypertension: A study of midlife African-American men. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2012;74:961–964. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182733665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Adler NE, Brody GH, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Epel ES. Discrimination, racial bias, and telomere length in African-American men. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;46:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers EC, Tull ES, Fraser HS, Mutunhu NR, Sobers N, Niles E. The relationship of internalized racism to body fat distribution and insulin resistance among African Adolescent youth. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2004;96:1594–1598. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE. “Shift-and-persist” strategies: Why low socioeconomic status isn’t always bad for health. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:135–158. doi: 10.1177/1745691612436694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–816. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Benkert RA, Flack JM. Large arterial elasticity varies as a function of gender and racism-related vigilance in Black youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen CI, Berment F, Magai C. A comparison of US-born African-American and African-Caribbean psychiatric outpatients. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1997;89:117–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WTL, Abramson LY, Devine PG, Hollon SD. Stereotypes, prejudice, and depression: The integrated perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:427–449. doi: 10.1177/1745691612455204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert D, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. 4th. Vol. 2. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 1998. pp. 504–553. [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathol-ogy. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaux K, Bikmen N, Gilkes A, Ventuneac A, Joseph Y, Payne YA, Steele CM. Becoming American: Stereotype threat effects in Afro-Caribbean immigrant groups. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2007;70:384–404. [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Durso LE, Latner JD, Hayashi K. Perceived discrimination is associated with binge eating in a community sample of non-overweight, overweight, and obese adults. Obesity Facts. 2012;5:869–880. doi: 10.1159/000345931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee G, Walsemann K. Does health predict the reporting of racial discrimination or do reports of discrimination predict health? Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:1676–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, Vega WA. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2010;44:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govia IO. Mechanisms involved in the psychological distress of Black Caribbeans in the United States (Unpublished doctoral dissertation) Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Birnbaum HG. The economic burden of depression in the U.S.: Societal and patient perspective. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2005;6:369–376. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell JP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the collaborative psychiatric epidemiology studies (CPES) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicken MT, Lee H, Ailshire J, Burgard SA, Williams DR. “Every shut eye, ain’t sleep”: The role of racism-related vigilance in racial/ethnic disparities in sleep difficulty. Race and Social Problems. 2013;5:100–112. doi: 10.1007/s12552-013-9095-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein MS, Young DM, Sanchez DT, Jackson JS. Vigilance in the discrimination-stress model for Black Americans. Health & Psychology. 2014;30:253–267. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.966104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson B, Smart Richman L, LaBelle O, Lem-pereur MS, Twenge JM. Experimental evidence that low social status is most toxic to well-being when internalized. Self and Identity. 2014;14:157–172. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2014.965732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Trier-weiler SJ, Torres M. Methodological innovations in the national survey of American life. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:289–298. doi: 10.1002/mpr.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, Williams DR. The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:196–207. doi: 10.1002/mpr.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C, Erving CL. Structural constraints and lived realities: Negotiating racial and ethnic identities for African Caribbeans in the United States. Journal of Black Studies. 2015;46:521–546. [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1212–1215. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Confronting institutionalized racism. Phylon. 2003;50:7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social behavior. 1999;40:208–230. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2676349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Üstün TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N, Carney D, Lancaster K, Waterman PD, Kosheleva A, Banaji M. Combining explicit and implicit measures of racial discrimination in health research. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1485–1492. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey KK, Sears KP, Govia IO, Forsythe-Brown I, Matusko N, Jackson JS. Substance use, mental disorders and physical health of Carib-beans at-home compared to those residing in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research in Public Health. 2015;12:710–734. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120100710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logie C, James L, Tharao W, Loufty M. Associations between HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, and depression among HIV-positive African, Caribbean, and Black women in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2013;27:114–122. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Mendes WB, Dovidio JF. Intergroup relations and health disparities: A social psychological perspective. Health Psychology. 2013;32:514–524. doi: 10.1037/a0030358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GL, Rue TC. Perceived discrimination and social networks among older African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Family & Community Health. 2012;35:300–311. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318266660f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina KM, Alegria M, Mahalingam R. A multiple-group path analysis of the role of everyday discrimination on self-rated physical health among Latina/os in the USA. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;45:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9421-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mplus (Version 7.3) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. Retrieved from http://statmodel.com/ugexcerpts.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- Myers HF. Ethnicity- and socio-economic status-related stresses in context: An integrative review and conceptual model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;35:888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gee G. Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL, Neville HA, Todd NR, Carter RT. Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2012;59:1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punyanunt-Carter NM. The perceived realism of African American portrayals on television. The Howard Journal of Communications. 2008;19:241–257. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in structural equation models. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE; 1993. pp. 163–180. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:111–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Phelan JC. Internalized stigma predicts erosion of morale among psychiatric outpatients. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Robert SM, Jackson JS. An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:1372–1379. doi: 10.1037/a0019869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton EK, Caldwell CH, Sellers RM, Jackson JS. The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black youth. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1288–1297. doi: 10.1037/a0012747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academic Press; 2003. Retrieved from http://www.nap.edu/catalog/10260/unequal-treatment-con-fronting-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-health-care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speight SL. Internalized racism: One more piece of the puzzle. The Counseling Psychologist. 2007;35:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 [Computer software] College Station, TX: Stata-Corp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. Cost of lost productive work time among U.S. workers with depression. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3135–3144. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]