Abstract

Hematopoietic cell survival and death is critical for development of a functional immune system. Here, we report that a protein kinase, TAK1, is selectively required for resident macrophage integrity during embryogenesis. Hematopoietic lineage-specific deletion of Tak1 gene (Tak1HKO) caused accumulation of cellular debris in the thymus in perinatal mice. Although no overt alteration in thymocytes and blood myeloid populations was observed in Tak1HKO mice, we found that thymic and lung macrophages were diminished. In the in vitro setting, Tak1 deficiency caused profound disruption of lysosomes and killed bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) without any exogenous stressors. Inhibition of the lysosomal protease, cathepsin B, partially blocked Tak1-deficient BMDM death, suggesting that leakage of the lysosomal contents is in part the cause of cell death. To identify the trigger of this cell death, we examined involvement of TNF and Toll-like receptor pathways. Among them, we found that deletion of Tnfr1 partially rescued cell death. Finally, we show that Tnfr1 deletion partially restored thymic and lung macrophages in vivo. These results suggest that autocrine and potentially paracrine TNF kills Tak1-deficient macrophages during development. Our results reveal that TAK1 signaling maintains proper macrophage populations through protecting lysosomal integrity.

Macrophages possess unique functional roles that are dependent on the microenvironment where they reside.1 During early embryogenesis, progenitors of macrophages migrate to several different sites in the embryo, uniquely differentiate, and colonize as tissue-resident macrophages, such as microglia, thymic macrophages and pulmonary macrophages.2 When invasion of pathogenic microorganisms occurs, tissue-resident macrophages along with recruited circulating monocytes provoke inflammatory responses. In addition to their role as responders to insult, tissue-resident macrophages are also critical for tissue integrity in the steady state. Because tissues constantly produce or acquire dead cells, cell debris, and excess lipoproteins, which belong to the family of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), tissues can become spontaneously inflamed through activation of DAMP receptors such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs).3 Resident macrophages are responsible for clearing DAMPs and preventing unnecessary inflammation. Thus, investigations to delineate the mechanisms by which tissue-resident macrophages differentiate and are maintained are critical for a fundamental understanding of tissue homeostasis. The mechanisms by which tissue-resident macrophages are uniquely differentiated toward specific types have begun to be elucidated.1, 4 However, although it is clear that tissue-resident macrophages are maintained separately from the bone marrow hematopoietic system, how their population is regulated or maintained is still largely undetermined.

TAK1 (MAP3K7) is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) family, and is activated by a diverse set of inflammatory stimuli including inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-1, and TLR ligands.5 In mouse models, tissue-specific deletion of the Tak1 gene causes cell death resulting in tissue injury in multiple tissues including the epidermis, the intestinal epithelium, and the vascular endothelium.6, 7, 8 A profound increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is causally associated with Tak1 deficiency-induced cell death.9, 10, 11 The mechanism by which Tak1 deficiency disrupts cellular redox homeostasis is not yet fully understood; however, impairment of several intracellular signaling cascades and transcription factors including but not limited to NF-κB, MAPKs including p38 and JNK, and the antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 has been implicated in increased ROS.5, 12 Interestingly, recent studies have revealed that not all tissues or cell types are damaged or killed by Tak1 deletion; for example, Tak1-deficient neurons do not exhibit any abnormalities,13 and some hematopoietic cells seem to be highly resistant to Tak1 deficiency as discussed below. Thus, sensitivities to Tak1 deficiency vary depending on cell type and the cellular context. It still remains to be determined which cell types are sensitive to Tak1 deficiency and the mechanism(s) by which Tak1-deficient cells die.

In the hematopoietic system, TAK1 is involved in maintenance of several specific cell types. We previously demonstrated that Tak1 deficiency impairs adult hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) maintenance.14 Competitive transplantation assays showed that Tak1-deficient bone marrow cells in adult mice are incapable of repopulating any types of hematopoietic cells.14, 15 In contrast, T or B cell-specific deletion of Tak1 skews subset populations of T and B cells but does not cause overt cell death in the in vivo setting.16, 17, 18, 19 Mice with myeloid-specific deletion of Tak1 were generated and characterized by two groups using the LysM-Cre deleter strain.20, 21 These mice exhibit an increased circulating neutrophil population and develop splenomegaly, and no overt increase in cell death is observed in vivo.20, 21 However, as the LysM-Cre system is not highly effective in several types of myeloid cells including resident macrophages22, 23, 24 and its inefficient recombination of floxed genes is known to cause artificial consequences,25 the role of TAK1 in hematopoietic cells should be further evaluated in other gene deletion systems.

In the current study, we investigated how TAK1 participates in the hematopoietic system by using the Vav-Cre system, which is expressed in all the hematopoietic compartments.26 Specifically, Vav1 (a GDP/GTP nucleotide-exchange factor for Rho/Rac) is expressed in erythro-myeloid progenitors and fetal HSCs that originate in the yolk sac during early embryogenesis, presumably starting around embryonic day 7.27 Endothelial cells also originate from the hemogenic endothelial cells.28, 29 However, Vav1 is expressed only in erythro-myeloid progenitors and fetal HSCs but not in endothelial cells, and Vav-Cre is thus suitable for the characterization of target genes in the embryonic hematopoietic system without affecting the endothelium. Furthermore, as erythro-myeloid progenitors give rise to tissue-resident macrophages, this system provides the means to characterize target genes in tissue-resident macrophages.22

Results

Hematopoietic-specific Tak1 deficiency impairs clearance of dead cells and causes perinatal lethality

TAK1 is required for proper development of the hematopoietic system and maintenance of adult HSC.14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 However, our understanding of the roles of TAK1 in various hematopoietic compartments, including those during embryogenesis, remains incomplete. Tie2 (an angiopoietin receptor)-Cre system, can recombine floxed genes during early embryogenesis in hemogenic endothelial cells, early precursors of hematopoietic cells,30 and is suitable for investigations of the entire hematopoietic system. However, as endothelial cells share the same origin, Tie2-Cre recombines floxed genes in endothelial cells. We previously demonstrated that Tak1 deletion with the Tie2-Cre deleter causes endothelial cell death and early embryonic lethality at embryonic day (E)10.5.6 We showed that erythrocytes are normally developed but blood vessel regression occurs at E10.5 in these mice, suggesting that endothelial cell autonomous defects but not hematopoietic abnormality cause blood vessel regression.6

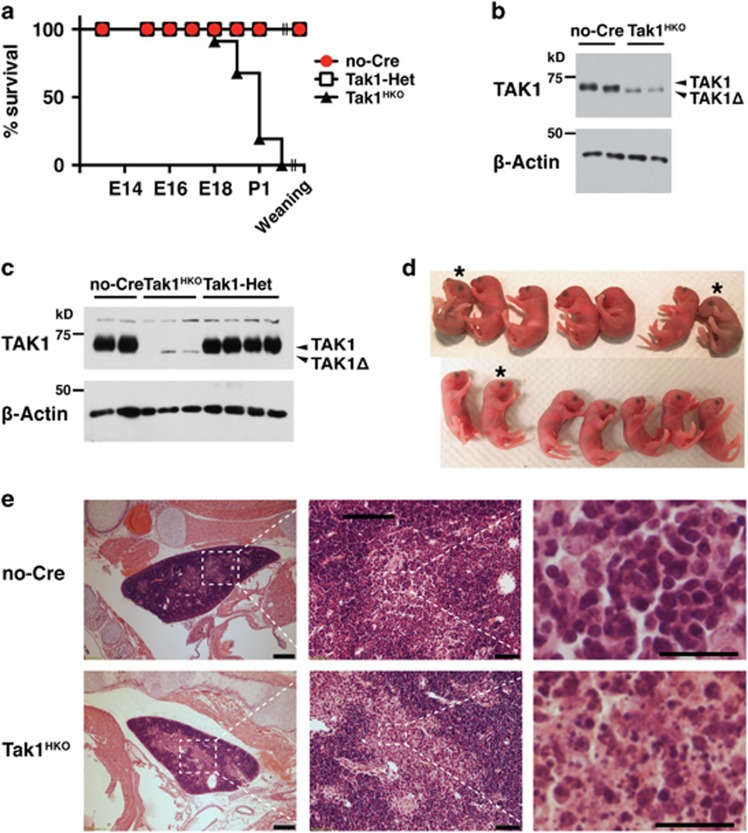

In the current study, we sought to determine the role of TAK1 specifically in the hematopoietic compartment. Vav-Cre was chosen as it is expressed in erythro-myeloid progenitors and fetal HSCs but not in endothelial progenitors.27, 31 We generated Vav-Cre Tak1flox/flox (Tak1HKO) mice and compared them with littermate Cre-negative Tak1flox/flox and heterozygous Tak1 deletion Vav-Cre Tak1flox/+ mice. Tak1HKO mice were found to suffer lethality between E18.5 and postnatal (P) day 1 (Figure 1a). We confirmed that intact TAK1 protein was diminished in all hematopoietic cells including thymocytes at E16.5 (Figure 1b) and in circulating blood cells at least by E18.5 (Figure 1c). We note here that Tak1-floxed gene expresses a truncated and non-functional form of TAK1 protein (TAK1Δ) when loxP recombination occurs, and TAK1Δ is less stable compare to intact TAK1.8, 17 Heterozygous deletion of Tak1 did not observably reduce the TAK1 protein level, suggesting that a single allele is sufficient for maintenance of the steady-state TAK1 protein level. Consistently, we did not observe any abnormality in Vav-Cre Tak1flox/+ (Tak1-Het) mice, as we also observed no abnormality in other tissue-specific heterozygous Tak1-deficient mice.6, 7, 8, 32

Figure 1.

Hematopoietic-specific Tak1 deficiency causes perinatal lethality. (a) Percentages of viable no-Cre (Tak1flox/flox or Tak1flox/+), Tak1-Het (vav-Cre Tak1flox/+), and Tak1HKO (vav-Cre Tak1flox/flox) embryos. The total numbers of animals analyzed including live and dead were no-Cre, 178; Tak1-Het, 110, Tak1HKO, 94. P<0.001 (log-rank test). (b) no-Cre control and Tak1HKO thymus were isolated from E16.5 mice and analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated targets. Recombined Tak1 gene expressed a truncated and non-functional TAK1 protein (TAK1Δ). β-actin is shown as a loading control. (c) no-Cre, Tak1-Het, and Tak1HKO blood were isolated from E18.5 mice and analyzed by immunoblotting for the indicated targets. (d) P0 littermates from the mating of Tak1flox/floxand Tak1flox/+ Vav-Cre parents. Asterisks indicate Tak1HKO mice. (e) H&E staining of E18.5 no-Cre and Tak1HKO thymus. Scale bars, 200 μm (left panels), 50 μm (middle panels), 20 μm (right panels)

Although Tak1HKO mice die around birth, we did not observe any overt clinical abnormalities except occasional mild cyanosis (Figure 1d). We performed histological analyses of tissue samples from live Tak1HKO and their littermate mice at P0. The prominent observable abnormality was found in the thymic medulla, where there was an accumulation of marked dead cell debris (Figure 1e, Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). We also note that the size of lung alveoli in Tak1HKO animals was reduced compared with that in the littermate controls (Supplementary Figure S3), which may be associated with cyanosis. By contrast, other organs were architecturally indistinguishable from those in control littermates (Supplementary Figure S3). We also performed histopathological evaluation of one E18.5 litter consisting of three Tak1HKO and three control embryos. At E18.5, no abnormality in the overall morphogenesis of Tak1HKO embryos was observed, indicating that hematopoietic TAK1 is not required for embryogenesis. No increase in apoptotic or necrotic cells was observed in the liver, intestine, kidney, heart, spleen, lung, brain and spleen. Thus, hematopoietic-specific Tak1 deletion does not impair normal morphogenesis or increase of cell death during embryogenesis, but causes a destruction of thymus and an abnormality in the lung architecture around birth.

Hematopoietic-specific deletion of Tak1 does not impair normal development of lymphocytes and myeloid cells

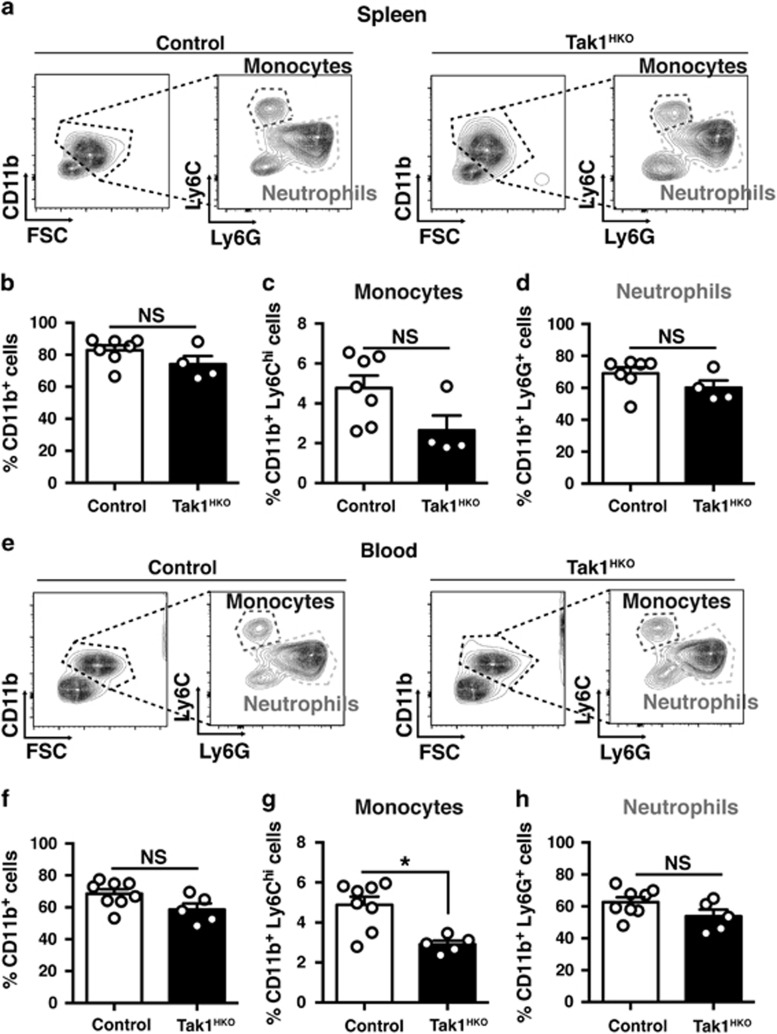

To determine the cause of Tak1HKO thymus abnormality, we first asked if Tak1 deficiency causes any abnormalities in hematopoietic cell compartments within the systemic immune system. We began by analyzing leukocytes in circulating blood and spleen isolated from live P0 Tak1HKO and littermate control mice (Figure 2). No difference in the proportions of CD11b+ (myeloid) and CD11b− (non-myeloid, including lymphoid) cells was observed between Tak1-deficient mice and controls in the circulating blood or the spleen (Figures 2a, b, e and f). Among myeloids, CD11b+ Ly6Chi (monocytes) and CD11b+ Ly6G+ (neutrophils) were similarly observed in the spleen and blood of Tak1HKO and controls mice (Figures 2a and e). Although Tak1HKO exhibited a trend of reduced myeloid population (Figures 2c and g), neutrophils were not altered by Tak1 deletion. These results demonstrate that TAK1 is dispensable for normal hematopoietic development of both myeloid and lymphoid cells in the spleen and circulating blood at least around birth in mice with exception of a slight decrease in monocyte population. Hence, the thymic abnormality in Tak1HKO is not caused by defects in the systemic hematopoiesis.

Figure 2.

Hematopoietic-specific Tak1 deletion does not impair the development of splenocytes and circulating myeloid cells. (a) Gating strategy and representative flow cytometry data of control (no-Cre and Tak1-Het) and Tak1HKO splenocytes at P0. (b) Total CD11b+ cells in P0 control (n=7) and Tak1HKO (n=4) spleen as a percent of total live cells. (c) CD11b+ Ly6Chi cells (monocytes) and (d) CD11b+ Ly6G+ cells (neutrophils) in P0 control (n=7) and Tak1HKO (n=4) spleen as a percent of total live cells. (e) Gating strategy and representative flow cytometry data of control (no-Cre and Tak1-Het) and Tak1HKO blood at P0. (f) Total CD11b+ cells in P0 control (n=8) and Tak1HKO (n=5) blood as a percent of total live cells. (g) CD11b+ Ly6Chi cells (monocytes) and (H) CD11b+ Ly6G+ cells (neutrophils) in P0 control (n=8) and Tak1HKO (n=4) blood as a percent of total live cells. Means±S.E. and all data points are shown. *P<0.05; NS, not significant (two-tailed Student's t-test with equal distributions)

Hematopoietic-specific deletion of Tak1 diminishes thymic and pulmonary macrophages

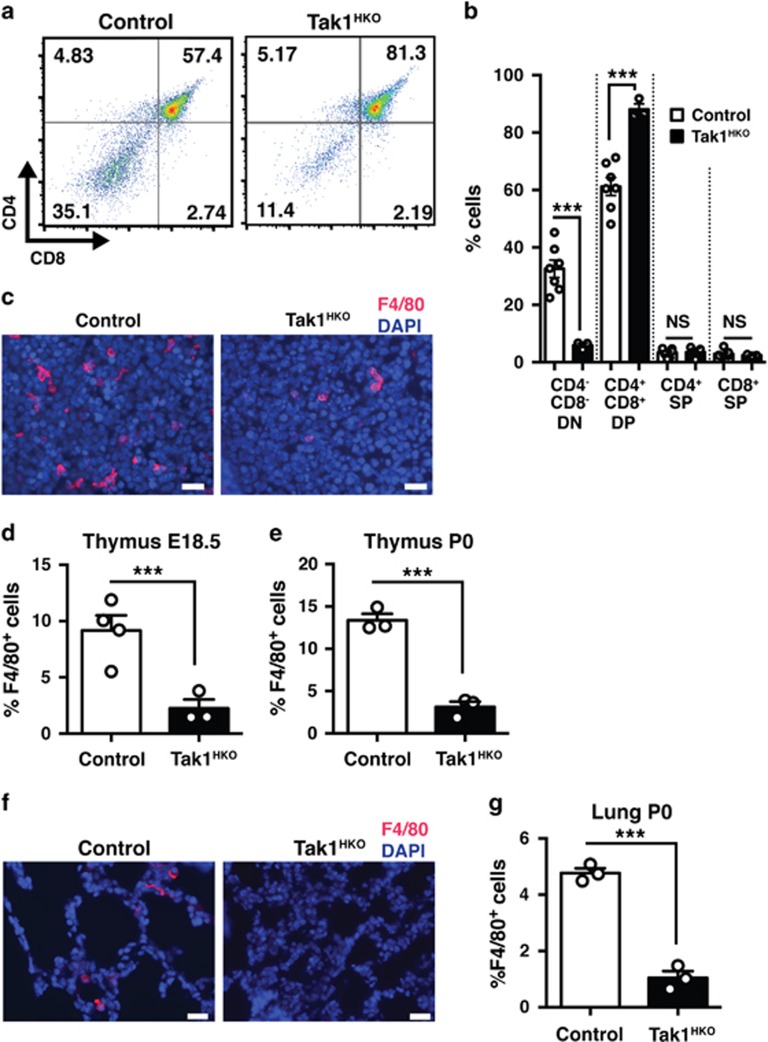

We next focused on the thymus. Accumulation of cell debris might be caused by increased thymocyte death during T-cell maturation in the thymus. We thus analyzed T-cell populations in the thymus. If T cells were dying during maturation, the number of CD4+ CD8+ double positive and CD4+ CD8− and/or CD4− CD8+ single positive cells should be decreased by Tak1 deficiency. Unexpectedly, we found increased CD4+ CD8+ double positive cells in Tak1HKO thymus, whereas the CD4− CD8− double negative population was decreased (Figures 3a and b). The numbers of mature CD4+ CD8− and CD4− CD8+ single positive cells were comparable between control and Tak1-deficient thymus (Figures 3a and b). Thus, Tak1 deficiency does not impair T-cell development and maturation. The CD4− CD8− double negative populations contain both naive T cells and other cell types in the thymus including thymic macrophages. Thymic macrophages have an indispensable role in clearance of dead thymocytes during T-cell development.33 Thus, Tak1 deficiency might impair thymic macrophages, which could cause accumulation of cell debris in the thymus. To test this possibility, we analyzed F4/80+ macrophages in the Tak1HKO and control thymus. The number of thymic macrophages was markedly reduced by Tak1 deficiency (Figures 3c–e), indicating that TAK1 is required for establishment and/or maintenance of thymic macrophages. This suggested the possibility that TAK1 also contributes to integrity of other tissue-resident macrophages. We analyzed F4/80+ macrophages in the lung and spleen of P0 Tak1HKO and control mice. The number of macrophages was also markedly reduced in the Tak1HKO lung and spleen compared with the controls (Figures 3f, g and Supplementary Figure S4). These results demonstrate that TAK1 is required for establishment and/or maintenance of resident macrophages in the thymus, lung and spleen.

Figure 3.

Hematopoietic-specific deletion of Tak1 diminishes thymic and pulmonary macrophages. (a) Thymocytes were isolated from E18.5 control (no-Cre and Tak1-Het, n=7) and Tak1HKO (n=3), and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating strategy and representative data of control and Tak1HKO including percent of cells in each quadrant are shown. (b) Quantification of percent DN, CD4− CD8−; DP, CD4+ CD8+; SPCD4, CD4+ CD8−; and SPCD8, CD4− CD8+ thymocytes of samples shown in a. (c) E18.5 control and Tak1HKO thymus was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining using anti-F4/80 antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. (d) Quantification of F4/80+ cells in in total DAPI stained cells of the thymus from E18.5 control (n=4) and Tak1HKO (n=3). (e) P0 thymus control (n=3) and Tak1HKO (n=3). (f) P0 control and Tak1HKO lung was analyzed by immunofluorescence staining using anti-F4/80 antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. (g) Quantification of F4/80+ cells in total DAPI stained cells. P0 control (n=3); Tak1HKO (n=3). Means±S.E. and all data points are shown. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant (two-tailed Student's t-test with equal distributions)

Tak1 deficiency impairs lysosomes and kills bone marrow-derived macrophages without exogenous stressors

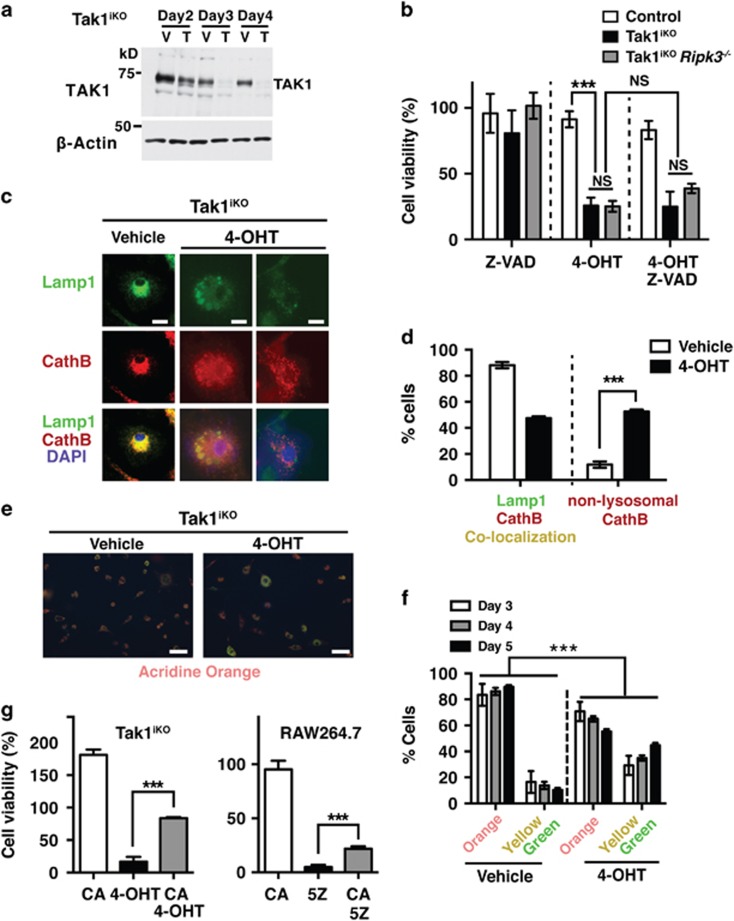

We next attempted to determine the mechanism by which Tak1 deficiency reduces resident macrophages. It has previously been reported that Tak1-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) spontaneously undergo cell death.20, 34, 35 Thus, loss of viability by Tak1 deficiency is likely to be the cause of reduced resident macrophages. However, the mechanism by which Tak1 deficiency spontaneously kills macrophages is still elusive. To gain mechanistic insights, we took advantage of the inducible gene deletion system. We prepared BMDM from mice having the ubiquitous inducible Cre deleter (Rosa26-CreERT)36 and Tak1-floxed genes (Tak1iKO). TAK1 was diminished in Tak1iKO BMDMs after 3 days treatment of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) (Figure 4a). Tak1-deficient cells including fibroblasts and keratinocytes die with apoptosis, and RIPK3-dependent necroptosis has also been implicated in cell death by Tak1 deficiency when Tak1-deficient cells are treated with a pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD-FMK (Z-VAD).5 However, we unexpectedly found that Tak1-deficient BMDM death could not be rescued by either single or combined inhibition of caspases (apoptosis) and/or RIPK3, a mediator of necroptosis (Figure 4b). Thus, Tak1-deficient macrophages die primarily not through either apoptosis or necroptosis.

Figure 4.

Tak1 deficiency impairs lysosomes and kills BMDMs. (a) Inducible Tak1-deficient (Tak1iKO) BMDM treated with vehicle alone (ethanol, V) or 0.3 μM 4-OHT (T) for 2, 3 and 4 days and analyzed by immunoblotting for TAK1. β-actin is shown as a loading control. (b) Measurement of percent cell viability of control (n=3), Tak1iKO (n=3), and Tak1iKO Ripk3−/− (n=4) BMDMs 5 days post 0.3 μM 4-OHT treatment using crystal violet viability assay. Some cells were incubated with Z-VAD-FMK (Z-VAD, 20 μM) for 3 days prior to fixation. (c and d) Tak1iKO BMDMs were treated with vehicle or 0.3 μM 4-OHT for 5 days. Lysosomal architecture disruption was observed in Tak1iKO BMDMs 5 days post 0.3 μM 4-OHT treatment. Lysosomal architecture was visualized by staining using anti-lamp1 (green) and anti-cathepsin B (CathB; red) antibodies. Scale bars, 10 μm. (e and f) Tak1iKO BMDMs were treated with vehicle or 0.3 μM 4-OHT. Lysosomal function was determined by incubating cells in acridine orange at 3, 4 and 5 days post 4-OHT treatment. Orange staining indicates normal functional lysosomal pH (around 3.5), and yellow or green staining indicates increased lysosomal pH. Scale bars, 50 μm. (g, Left) Viability of Tak1iKO BMDMs treated 30 μM CA-074Me (cathepsin B inhibitor, CA), 0.3 μM 4-OHT, or 30 μM CA+0.3 μM 4-OHT. Percent live Tak1iKO cells relative to the vehicle-treated same genotype cells are shown. (Right) RAW264.7 cells were treated with 30 μM CA, 200 nM 5Z-7-oxozeaenol (5Z), or 30 μM CA+200 nM 5Z. All graphs, means±S.D.; ***P<0.001; NS, not significant (one-way ANOVA)

We explored other modes of cell death, including pyroptosis and lysosome malfunction-induced cell death. The pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK, which inhibits the pyroptosis mediator caspase 1 and caspase 11,37 did not block Tak1-deficient BMDM death (Figure 4b), suggesting that pyroptosis is not the major cause of cell death. Notably, however, Tak1iKO BMDMs exhibited abnormal lysosomal architecture (Figure 4c), and co-localization of the lysosomal protease, cathepsin B and a lysosome marker, lamp1, was disrupted (Figures 4c and d). Furthermore, acridine orange staining revealed that Tak1 deficiency increased dysfunctional lysosomes with an elevated pH (yellow and green) (Figures 4e and f). Such abnormalities in lysosomes were not observed in 4-OHT treated BMDMs having a different floxed gene together with Rosa26-CreERT (Supplementary Figure S5), indicating that neither 4-OHT nor Cre are the cause of the lysosome abnormalities. Thus, Tak1 deficiency is the cause of lysosomal abnormality. We asked whether inhibition of a lysosomal protease, cathepsin B, could restore cell death in Tak1iKO BMDMs. Inhibition of cathepsin B increased cell number even in wild type BMDMs about 2-fold (Figure 4g, left graph), suggesting that inhibition of cathepsins generally improves BMDM survival and/or proliferation. Importantly, inhibition of cathepsin B increased the number of Tak1iKO BMDMs with higher efficiency (3-fold) than wild type BMDMs, suggesting that cathepsin activity is responsible, at least in part, for Tak1iKO BMDM death. The mouse macrophage cell line, RAW264.7, was also killed by a selective inhibitor of TAK1, 5z-7oxozeanol38 (Figure 4g, right graph). In RAW264.7 cells, inhibition of cathepsin B alone did not alter cell viability but partially rescued TAK1 inhibitor-induced cell death (Figure 4g). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Tak1 deficiency impairs lysosomes, and that lysosomal dysfunction contributes to macrophage death.

TNF is the trigger of cell death

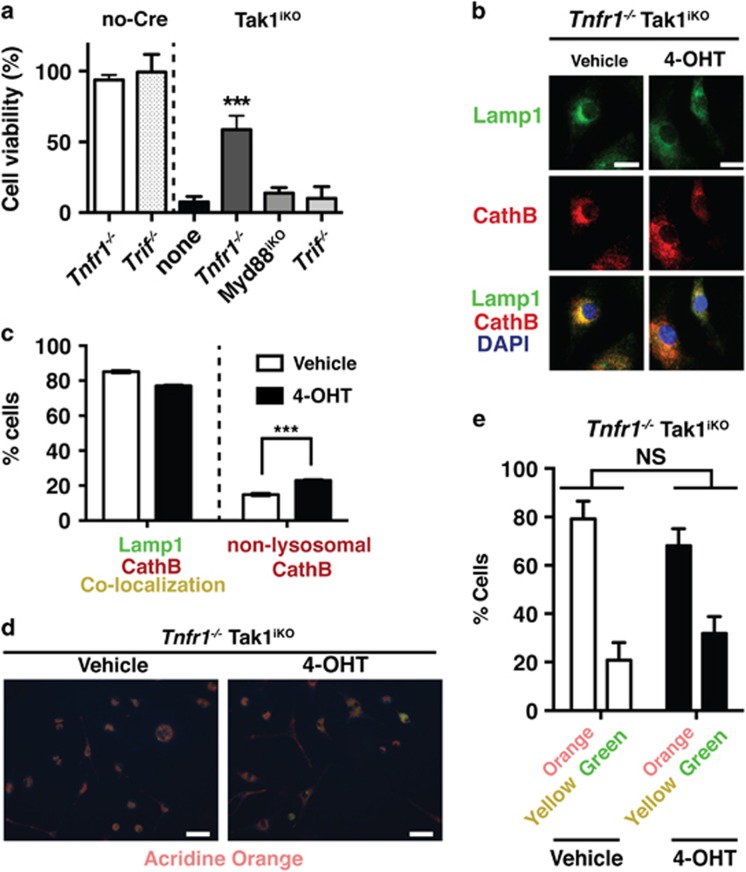

Tak1-deficient BMDMs die without any exogenous stimuli in standard culture conditions. TAK1 is activated by a number of stressors including inflammatory cytokines and TLR ligands including dead cell-derived molecules (i.e., DAMPs). Macrophages produce inflammatory cytokines, TNF and IL-1, and dead cells are unavoidably present in the medium during isolation and culture of BMDMs. We asked whether TNF, IL-1 or TLR signaling is involved in Tak1-deficient BMDM death. To examine the TNF pathway, we utilized TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1)-deficient (Tnfr1−/−) mice.39 IL-1 and TLR pathways share the same adaptor MyD88, and some TLRs additionally utilize another adaptor, TRIF.40 To examine these pathways, we generated Rosa26-CreERT Tak1flox/flox Myd88flox/flox and Rosa26-CreERT Tak1flox/flox Trif−/− mice. An earlier study using the LysM-Cre system reported that TNF receptor deficiency rescues macrophage differentiation in myeloid-specific Tak1 deletion bone marrow cells.35 However, involvement of TNF in macrophage viability after the completion of differentiation was not clear. We found that Tnfr1 deficiency effectively albeit incompletely rescued Tak1iKO BMDM death (Figure 5a), whereas deletion of either Myd88 or Trif did not restore cell viability (Figure 5a). This suggests that TNF is, at least in part, the cause of Tak1iKO BMDM death. Furthermore, we found that only a small proportion of cells exhibited abnormal localization of cathepsin B in the Tnfr1-deficient background (Figure 5b). Non-functional lysosomes with elevated pH were not increased by Tak1 deletion on the Tnfr1−/− background (Figures 5c and d). Collectively, these results suggest that TNF is the major cause of lysosomal dysfuntion, and associated cell death, in Tak1-deficient BMDMs.

Figure 5.

Tnfr1 deletion partially protects lysosome and blocks cell death in Tak1-deficient BMDMs. (a) Percent cell viability of Tak1iKO BMDMs in Tnfr1−/− (n=3), Myd88iKO(n=3), or Trif−/−(n=3) backgrounds. Crystal violet stained 4-OHT-treated cells relative to those of the vehicle-treated same genotype cells were calculated and shown as percentages. Means±S.D.; ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA). (b and c) Tak1iKO Tnfr1−/− and no-Cre Tnfr1−/− BMDMs were treated with vehicle or 0.3 μM 4-OHT for 5 days. Lysosomal architecture was visualized by staining using anti-lamp1 (green) and anti-cathepsin B (CathB; red) antibodies. Scale bar, 10 μm. Means±S.D.; ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA). (d and e) Lysosomal function was determined by incubating cells in acridine orange at 4 days post 4-OHT treatment. Orange staining indicates normal functional lysosomal pH (around 3.5), and yellow or green staining indicates increased lysosomal pH. Scale bar, 50 μm. Means±S.D.; ***P<0.001 (one-way ANOVA)

Tnfr1 deletion partially rescues developmental abnormalities and loss of resident macrophages

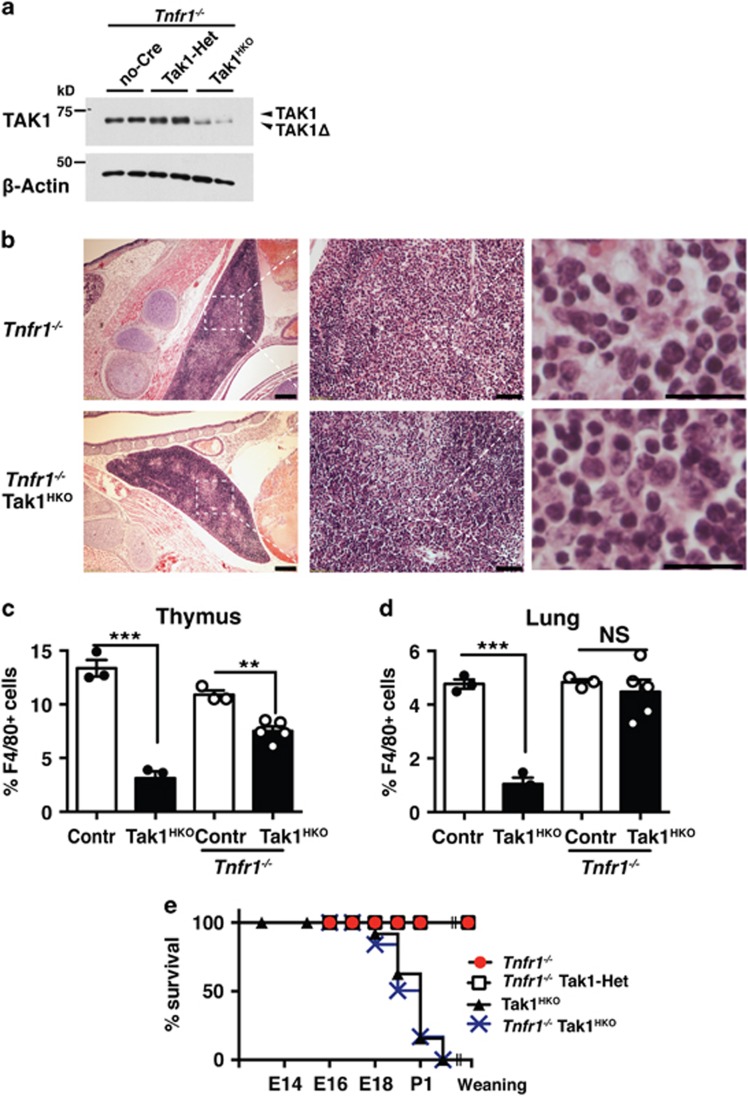

We finally examined whether TNF-induced cell death is the cause of diminished resident macrophages in Tak1HKO mice. We generated and analyzed Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− mice. Tnfr1−/− mice are normal under standard housing conditions, and there is no overt abnormality in morphogenesis.41 TAK1 was effectively depleted in the Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− thymus at P0 (Figure 6a), similar to Tak1HKO shown in Figure 1b. However, the cell debris, which was profoundly observed in the Tak1HKO thymus (Figure 1e), was not seen in the Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− thymus (Figure 6b). The number of thymic macrophages was still reduced in the Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− thymus (Figure 6c), but it was improved compared with those in Tak1HKO thymus (Figures 3d and f). Furthermore, the number of pulmonary macrophages was restored by Tnfr1 deficiency (Figure 6d). These results demonstrate that, although other unidentified causes contribute to reduction of Tak1-deficient macrophages, TNF is one of the major triggers of diminished resident macrophages in Tak1HKO mice. However, we note that animal mortality was not rescued by Tnfr1 deletion (Figure 6e), suggesting that reduction of macrophages is not the prominent cause of animal mortality, and also that the mortality is TNF-independent. Collectively, although we could not identify the cause of animal mortality, our results reveal that TAK1 is a critical regulator of macrophage maintenance in the perinatal hematopoietic system by preventing TNF-induced lysosomal damage.

Figure 6.

Tnfr1 deletion partially restores tissue-resident macrophages and developmental abnormalities. (a) no-Cre Tnfr1−/−, Tak1-Het Tnfr1−/−, and Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− thymocytes were isolated from E18.5 mice and analyzed by immunoblotting. Recombined Tak1 gene expressed a truncated and non-functional TAK1 protein (TAK1Δ). β-actin is shown as a loading control. (b) H&E staining of E18.5 Tnfr1−/− and Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− thymus. Scale bars, 200 μm (left panels), 50 μm (middle panels), 20 μm (right panels). (c and d) Quantification of F4/80+ cells in DAPI stained cells in control (Contr) and Tak1HKO in wild type (left two bars) and Tnfr1−/−background (right two bars). The left two bars are the same data shown in Figures 3e and g. (c) P0 Tnfr1−/− (n=3) and Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− (n=3) thymus; and (d) P0 Tnfr1−/− (n=3) and Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− (n=5) lungs. Means±S.E. and all data points are shown. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant (two-tailed Student's t-test with equal distributions). (e) Percentages of viable Tnfr1−/−, Tak1-Het Tnfr1−/−, and Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/− mice. Viability data of Tak1HKO (Figure 1a) are also included as a comparison. The total numbers of animals analyzed including live and dead were Tnfr1−/−, 100; Tak1-Het Tnfr1−/−, 51, Tak1HKO Tnfr1−/−, 48; P<0.0001 (log-rank test)

Discussion

TAK1 is a signaling molecule that both promotes inflammatory responses and guards against cell death during inflammation in several cell types. We previously reported that Tak1-deficient epithelial and endothelial cells die, causing severe tissue damage.6, 7, 8, 10, 11 In the current study, we show that Tak1 deficiency uniquely causes cell death in macrophages among hematopoietic cells during embryogenesis. Although Tak1-deficient thymocytes, splenocytes and circulating myeloid cells develop normally, Tak1 deficiency diminishes thymic and lung-resident macrophages. This raises a question as to why certain cell types are selectively sensitive to Tak1 deficiency. One possibility is that proliferative cells may be sensitive to Tak1 deficiency. This idea is consistent with the fact that constantly renewing tissues such as the epidermis and the intestinal epithelium are highly sensitive to Tak1 deficiency,7, 8 whereas neurons, which are mostly post-mitotic, are resistant to Tak1 deficiency.13 However, it is inconsistent with the fact that embryonic hematopoietic progenitors are highly proliferative but the hematopoietic system developed normally in Tak1HKO mice. Furthermore, cultured fibroblasts are also highly proliferative under standard culture conditions; however, Tak1 deletion does not impair cell viability.5 In contrast, adult HSCs are known to be slowly self-renewing cells, but they are effectively depleted by Tak1 gene deletion.14 Similarly, cultured macrophages (BMDMs) are mostly post-mitotic or very slow growing after completion of the differentiation processes, but they die upon Tak1 gene deletion. Thus, cell proliferation is unlikely to be the determinant of the sensitivity to Tak1 deficiency.

Tak1-deficient fibroblasts and keratinocytes undergo cell death when they are treated with TNF.8, 42 TNF treatment induces accumulation of ROS in Tak1-deficient cells. Similarly, ablation of Tak1 activity in BMDMs highly upregulates ROS.43 TNF triggers cellular ROS production and phagocytic macrophages produce ROS.44, 45 Furthermore, ROS participate in adult HSC renewal and differentiation,46, 47 which may be further upregulated by Tak1 deficiency. These issues raise the possibility that ROS may be the determinant of Tak1 sensitivity. Although all cells constantly produce ROS as by-products of respiration, cells producing ROS beyond a certain level such as macrophages and TNF-treated fibroblasts may perhaps be killed if functional TAK1 is absent. We have previously reported that several cellular antioxidant enzymes such as glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 and an antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 are downregulated by Tak1 deficiency.10, 11, 12 Although the molecular mechanism by which TAK1 regulates ROS is not fully understood, ablation of TAK1 seems to reduce the capacity of the cellular antioxidant system, resulting in accumulation of a cell-killing level of ROS if cells actively produce ROS.

Increased ROS are commonly and causally associated with cell death in Tak1-deficient keratinocytes, intestinal epithelial cells, and macrophages; however, the pathways of cell death vary depending on the cellular context. Caspase activity is profoundly upregulated in Tak1-deficient epidermis and intestinal epithelium as well as TNF-treated Tak1-deficient keratinocytes and fibroblasts,10, 11, 42 indicating that they die predominantly through apoptosis. Earlier studies also implicate TAK1 in programmed necrosis, so-called necroptosis, in the intestinal epithelium and macrophages.32, 35 Here, we show that Tak1 deficiency causes lysosomal abnormality in macrophages. ROS are implicated in many types of cells death including apoptosis, necroptosis, and lysosomal rupture.48, 49, 50 ROS could trigger apoptosis through activation of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and ROS-induced necroptotic protein assembly in macrophages. Our results demonstrate that apoptosis and necroptosis are not major forms of Tak1-deficient macrophage death. Phagocytic macrophages possess highly active phagosome-lysosomes, and lysosomal enzymes are highly expressed in macrophages. It is therefore possible that, due to such high lysosomal activity, Tak1 deficiency may predominantly cause lysosomal damage through accumulation of ROS in macrophages but not other cell types.

Tissue-resident macrophages support tumor growth by clearing undesired molecules, supplying growth factors, and inducing angiogenesis.51 Thus, the cell type specific sensitivity to Tak1 deficiency may be useful for developing approaches to manipulate macrophages in tumors. However, inhibition of TAK1 activity such as application of pharmacological inhibitors of TAK1 is anticipated to cause a number of undesired consequences in normal tissues based on the mouse studies using tissue-specific deletion of Tak1. The potential deleterious conditions include epithelial tissue damage7, 8 and skewing of adaptive immune cell populations,16, 17, 18, 19 which could lead to chronic inflammatory diseases if inhibition of TAK1 is prolonged. In contrast to prolonged inhibition of TAK1, temporary inhibition or inducible deletion of Tak1 gene has thus far exhibited promising outcomes. Epidermal-specific inducible Tak1 deletion can induce tumor regression in skin papilloma but does not cause observable injury in the normal skin.9 Treatment with a selective TAK1 inhibitor 5z-7oxozeanol38 effectively blocks tumor growth without overt toxicity.52 Thus, although inhibition of TAK1 must be entertained with considerable caution, regulated inhibition of TAK1 may be potentially useful to selectively kill macrophages without affecting adaptive immunity in certain contexts.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Tak1-floxed (Tak1flox/flox) mice have been described previously,17 and were backcrossed at least seven times to C57BL/6. Vav-Cre (Jax mice, B6.Cg-Tg(Vav1-icre)A2Kio/J),26, 53 Rosa26-CreERT (Jax mice, B6;129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT)Nat/J),36 Tnfr1−/− (B6.129-Tnfrsf1atm1Mak/J)39 and Ripk3−/−54 mice were bred in our facility to produce the genotypes used. For characterization of Tak1HKO (vav-Cre Tak1flox/flox), littermate and wild type (no-Cre Tak1flox/flox) and heterozygous Tak1 deletion (vav-Cre Tak1flox/+) mice, which were phenotypically indistinguishable, were used as controls. Rosa26-CreERT Tab2flox/flox BMDMs were also used as controls, which were described previously.34, 55 Animal viability was calculated based on the assumption that Tak1HKO mice were born at a Mendelian ratio. All animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the North Carolina State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies and reagents

TAK1,56 F4/80 (BM8, eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), CD16/32 (93, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), CD4 (RM4-5, BioLegend), CD8a (53-6.7, BioLegend), CD11b (M1/70, BioLegend), Ly6C (HK1.4, BioLegend), Ly6G (1A8, BioLegend), cathepsin B (FL-339, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), Lamp1 (Anti-Human CD107a, eBioscience or H4A3, Santa Cruz), and β-actin (AC-15, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) antibodies were used. Human recombinant TNFα (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), Z-VAD-FMK (Z-VAD) (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA) and acridine orange (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were used. The TAK1 kinase inhibitor, 5Z-7-oxozeaenol (5Z) was described previously.38

Histology and immunofluorescence staining of embryos

Embryo and neonate fixation and staining were performed using the method described previously.57 Briefly, E18.5 and P0 mice were killed, blanched in boiling water for 20 s, and immersed in an ice water bath to permit the removal of the epidermis. An incision was also made from the right clavicle to the pubic bone, opening the thoracic and abdominal cavities for improved penetration of fixative and processing reagents. Animals were fixed in Bouin's solution for 48 h at room temperature on a shaker followed by multiple 70% ethanol washes for 30 min each to remove excess fixative from the tissue before histiologic processing. E18.5 embryos from one litter consisting of three Tak1HKO and three controls (no-Cre and heterozygous deletion) were step-sectioned dorsal to ventral at 300 μms, six serial sections (6 μms) were collected were stained with haemotoxylin and eosin, and the sections were pathologically evaluated by two board certified pathologists. For immunofluorescence staining of F4/80, 4% paraformaldehyde fixed embryo tissues were embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) media, and 4–6 μm cryosections were stained using anti-F4/80 (1 : 300) overnight at 4 °C. Bound antibodies were visualized by the Alexa Fluor 594 and 488 fluorescence dye-conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher Scientific). For quantification, more than 10 randomly digital images from each sample with the same exposure time were used.

Flow cytometric analysis

Whole blood, thymus and spleen cells were isolated with Hank's balanced salt solution without magnesium and calcium (HBSS(−)). The cells were then suspended in 0.83% ammonium chloride for 5 min at room temperature to lyse red blood cells and washed with HBSS(−). Cells were resuspended in HBSS(−) and filtered to obtain single cell suspension, which was confirmed by a pulse geometry gate, FSC-A versus FSC-H. The cells were incubated for 20 min on ice with anti-CD16/32 antibody to block FcγRII/III, followed by incubation with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against cell surface antigens as described above. After labeling, cells were washed once with HBSS(−), resuspended in HBSS(−) and analyzed on FACS LSRII (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and FlowJo (Version 10.1, FlowJo.LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). Debris was removed using a standard FSC versus SSC gating, and the subsequent gating strategy was shown in Figure 2.

BMDMs and RAW264.7 cells

Bone marrow cells from indicated genotypes, Tak1iKO (Rosa26-CreERT Tak1flox/flox) and other double deletion and littermate age-matched no-Cre control mice were isolated using a standard method and cultured in macrophage media containing 70% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (Hyclone) and 50 I.U./ml penicillin–streptomycin supplemented with 30% L929-conditioned media at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After 3-day culture, fully differentiated bone marrow-derived macrophages were re-plated and treated with 0.3 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) or vehicle (ethanol) alone for 2–5 days to achieve gene deletion. Mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (Hyclone, San Angelo, TX, USA) and 50 I.U./ml penicillin–streptomycin.

Crystal violet assay

BMDMs were plated onto 12- or 24-well plates and treated with 0.3 μM 4-OHT or vehicle for 2 days and Z-VAD-FMK, Z-VAD (20 μM), or TNF (20 ng/ml) for 3 additional days. RAW264.7 cells, cells were pre-treated with inhibitors and subsequently treated with 5Z-7 oxozeaenol. Cells were fixed using 10% formalin, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet solution. The dye was eluted and analyzed at 595 nm.

Western blotting

BMDMs were lysed in extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 12.5 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 20 μM aprotinin, 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 nM Calyculin A) and incubated on ice for 30 min. Cell extracts were resolved using SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-P membranes (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). The membranes were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies, and the bound antibodies were visualized with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies using the ECL (GE Healthcare) or SuperSignal West Femto (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Immunofluorescence staining of BMDMs

BMDMs were seeded on glass coverslips in 6-well plates, were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and were permeabilized with 0.5 % Triton X-100 in PBS for 10–30 min at room temperature. The fixed cells were blocked with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin for 30 min at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-Lamp1 (1:100) and anti-cathepsin B antibodies (1:300) followed by incubation with anti-rat and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa 594 or Alexa 488 (1:500, ThermoFisher Scientific). The coverslips were mounted with 50% glycerol and were examined by a fluorescence microscope (model BX41; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and camera (model DP80; Olympus) at room temperature. For quantification, more than 10 randomly photographed pictures from each sample with the same exposure time were used.

Acridine orange staining

BMDMs were plated and incubated with 0.3 μM 4-OHT or vehicle for 2–5 days, and stained for 15 min with 10 μg/ml acridine orange in 1 × PBS. The images were taken using a UV filter (excitation 450–480 nm). For quantification, more than 10 randomly photographed pictures from each sample with the same exposure time were used.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted using at least three mice as indicated in figure legends and the results are confirmed by at least three separately performed experiments. The column graphs represent the mean±S.D. or S.E. as indicated. For data using in vivo samples, all data points are shown. Differences between experimental groups were assessed for significance by using the one-way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, or the unpaired Student's t-test (two-tailed) with equal distributions. For survival assay, the log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test was used.

Acknowledgments

We thank S Akira for Tak1-floxed mice, and V Dixit and K Newton for Ripk3−/− mice. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM068812 and GM112986 (to JN-T), and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Intramural Grant Z01 ES102005 (to MBF). YS was partly supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 ES007046.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by G Raschella'

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity 2016; 44: 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin Y, Mortha A, Rahman A, Merad M. Regulation of macrophage development and function in peripheral tissues. Nat Rev Immunol 2015; 15: 731–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10: 826–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M et al. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell 2014; 159: 1312–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaly SR, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Morioka S. TAK1 control of cell death. Cell Death Differ 2014; 21: 1667–1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka S, Inagaki M, Komatsu Y, Mishina Y, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 kinase signaling regulates embryonic angiogenesis by modulating endothelial cell survival and migration. Blood 2012; 120: 3846–3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajino-Sakamoto R, Inagaki M, Lippert E, Akira S, Robine S, Matsumoto K et al. Enterocyte-derived TAK1 signaling prevents epithelium apoptosis and the development of ileitis and colitis. J Immunol 2008; 181: 1143–1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori E, Matsumoto K, Sanjo H, Sato S, Akira S, Smart RC et al. TAK1 is a master regulator of epidermal homeostasis involving skin inflammation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 19610–19617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori E, Matsumoto K, Zhu S, Smart RC, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. Ablation of TAK1 upregulates reactive oxygen species and selectively kills tumor cells. Cancer Res 2010; 70: 8417–8425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajino-Sakamoto R, Omori E, Nighot PK, Blikslager AT, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TGF-β-activated kinase 1 signaling maintains intestinal integrity by preventing accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the intestinal epithelium. J Immunol 2010; 185: 4729–4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omori E, Morioka S, Matsumoto K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 regulates reactive oxygen species and cell death in keratinocytes, which is essential for skin integrity. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 26161–26168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto K, Simmons AN, Kajino-Sakamoto R, Tsuji Y, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 regulates the Nrf2 antioxidant system through modulating p62/SQSTM1. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016; 25: 953–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sai K, Morioka S, Takaesu G, Muthusamy N, Ghashghaei HT, Hanafusa H et al. TAK1 determines susceptibility to endoplasmic reticulum stress and leptin resistance in the hypothalamus. J Cell Sci 2016; 129: 1855–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu G, Inagaki M, Takubo K, Mishina Y, Hess PR, Dean GA et al. TAK1 (MAP3K7) signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cells through TNF-dependent and -independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e51073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang M, Wei X, Guo Y, Breslin P, Zhang S, Zhang S et al. TAK1 is required for the survival of hematopoietic cells and hepatocytes in mice. J Exp Med 2008; 205: 1611–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Sanjo H, Tsujimura T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T et al. TAK1 is indispensable for development of T cells and prevention of colitis by the generation of regulatory T cells. Int Immunol 2006; 18: 1405–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Sanjo H, Takeda K, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Yamamoto M, Kawai T et al. Essential function for the kinase TAK1 in innate and adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2005; 6: 1087–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan YY, Chi H, Xie M, Schneider MD, Flavell RA. The kinase TAK1 integrates antigen and cytokine receptor signaling for T cell development, survival and function. Nat Immunol 2006; 7: 851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HH, Xie M, Schneider MD, Chen ZJ. Essential role of TAK1 in thymocyte development and activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006; 103: 11677–11682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajibade AA, Wang Q, Cui J, Zou J, Xia X, Wang M et al. TAK1 negatively regulates NF-κB and p38 MAP kinase activation in Gr-1+CD11b+ neutrophils. Immunity 2012; 36: 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe B, Lai Y, Hur L, Orozco NM, Wang J, Campos AD et al. Deletion of TAK1 in the myeloid lineage results in the spontaneous development of myelomonocytic leukemia in mice. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e51228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wegener JE, Huang TW, Sripathy S, De Jesus-Cortes H, Xu P et al. Wild-type microglia do not reverse pathology in mouse models of Rett syndrome. Nature 2015; 521: E1–E4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmann T, Wieghofer P, Muller PF, Wolf Y, Varol D, Yona S et al. A new type of microglia gene targeting shows TAK1 to be pivotal in CNS autoimmune inflammation. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16: 1618–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao K, Kobayashi T, Moro K, Ohyama M, Adachi T, Kitashima DY et al. Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nat Immunol 2012; 13: 744–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannella KM, Barron L, Borthwick LA, Kindrachuk KN, Narasimhan PB, Hart KM et al. Incomplete deletion of IL-4Rα by LysM(Cre) reveals distinct subsets of M2 macrophages controlling inflammation and fibrosis in chronic schistosomiasis. PLoS Pathog 2014; 10: e1004372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvy S, Metcalf D, Gibson L, Bath ML, Harris AW, Adams JM. Promoter elements of vav drive transgene expression in vivo throughout the hematopoietic compartment. Blood 1999; 94: 1855–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Yokomizo T, Zeigler BM, Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Runx1 is required for the endothelial to haematopoietic cell transition but not thereafter. Nature 2009; 457: 887–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, Li Y, De Obaldia ME, Yang Q, Yzaguirre AD, Yamada-Inagawa T et al. Erythroid/myeloid progenitors and hematopoietic stem cells originate from distinct populations of endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9: 541–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdiguero EG, Geissmann F. The development and maintenance of resident macrophages. Nat Immunol 2016; 17: 2–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkola HK, Orkin SH. The journey of developing hematopoietic stem cells. Development 2006; 133: 3733–3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegemund S, Shepherd J, Xiao C, Sauer K. hCD2-iCre and Vav-iCre mediated gene recombination patterns in murine hematopoietic cells. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0124661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons AN, Kajino-Sakamoto R, Ninomiya-Tsuji J. TAK1 regulates Paneth cell integrity partly through blocking necroptosis. Cell Death Dis 2016; 7: e2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KS. Beginnings of a good apoptotic meal: the find-me and eat-me signaling pathways. Immunity 2011; 35: 445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaly SR, Morioka S, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Takaesu G. Activated macrophage survival is coordinated by TAK1 binding proteins. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e94982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamothe B, Lai Y, Xie M, Schneider MD, Darnay BG. TAK1 is essential for osteoclast differentiation and is an important modulator of cell death by apoptosis and necroptosis. Mol Cell Biol 2013; 33: 582–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badea TC, Wang Y, Nathans J. A noninvasive genetic/pharmacologic strategy for visualizing cell morphology and clonal relationships in the mouse. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 2314–2322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagar JA, Miao EA. Detection of cytosolic bacteria by inflammatory caspases. Curr Opin Microbiol 2014; 17: 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kajino T, Ono K, Ohtomo T, Matsumoto M, Shiina M et al. A resorcylic acid lactone, 5Z-7-oxozeaenol, prevents inflammation by inhibiting the catalytic activity of TAK1 MAPK kinase kinase. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 18485–18490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer K, Matsuyama T, Kundig TM, Wakeham A, Kishihara K, Shahinian A et al. Mice deficient for the 55 kd tumor necrosis factor receptor are resistant to endotoxic shock, yet succumb to L. monocytogenes infection. Cell 1993; 73: 457–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and their crosstalk with other innate receptors in infection and immunity. Immunity 2011; 34: 637–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha-deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med 1996; 184: 1397–1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka S, Broglie P, Omori E, Ikeda Y, Takaesu G, Matsumoto K et al. TAK1 kinase switches cell fate from apoptosis to necrosis following TNF stimulation. J Cell Biol 2014; 204: 607–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Wu D, Huang DY, Lin WW. TAK1 inhibition-induced RIP1-dependent apoptosis in murine macrophages relies on constitutive TNF-alpha signaling and ROS production. J Biomed Sci 2015; 22: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Morgan MJ, Choksi S, Liu ZG. TNF-induced activation of the Nox1 NADPH oxidase and its role in the induction of necrotic cell death. Mol Cell 2007; 26: 675–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD, Neish AS. Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: a double-edged sword revisited. Annu Rev Pathol 2014; 9: 119–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang Y-Y, Sharkis SJ. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood 2007; 110: 3056–3063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludin A, Gur-Cohen S, Golan K, Kaufmann KB, Itkin T, Medaglia C et al. Reactive oxygen species regulate hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal, migration and development, as well as their bone marrow microenvironment. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014; 21: 1605–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrom KM, Finkel T. Cellular mechanisms and physiological consequences of redox-dependent signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Galluzzi L, Vanden Berghe T, Kroemer G. Molecular mechanisms of necroptosis: an ordered cellular explosion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2010; 11: 700–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene 2008; 27: 6434–6451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Pittet MJ. The role of myeloid cells in cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer 2016; 16: 447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Sweeney MF, Yu M, Burger A, Greninger P, Benes C et al. TAK1 inhibition promotes apoptosis in KRAS-dependent colon cancers. Cell 2012; 148: 639–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer J, Williams A, Skavdis G, Harker N, Coles M, Tolaini M et al. Transgenic mice with hematopoietic and lymphoid specific expression of Cre. Eur J Immunol 2003; 33: 314–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton K, Sun X, Dixit VM. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-κBs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 1464–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjo H, Takeda K, Tsujimura T, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Akira S. TAB2 is essential for prevention of apoptosis in fetal liver but not for interleukin-1 signaling. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Kishimoto K, Hiyama A, Inoue J, Cao Z, Matsumoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-IκB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature 1999; 398: 252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolon B, Duryea D, Foley JF. Histotechnological processing of developing mice. In: Bolon B (ed). Pathology of the Developing Mouse: A Systematic Approach. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.