Abstract

Young children are sensitive to the importance of apologies, yet little is known about when and why parents prompt apologies from children. We examined these issues with parents of 3-10-year-old children (N = 483). Parents judged it to be important for children to apologize following both intentional and accidental morally-relevant transgressions, and they anticipated prompting apologies in both contexts, showing an ‘outcome bias’ (i.e., a concern for the outcomes of children’s transgressions rather than for their underlying intentions). Parents viewed apologies as less important after children’s breaches of social convention; parents recognized differences between social domains in their responses to children’s transgressions. Irrespective of parenting style, parents were influenced in similar fashion by particular combinations of transgressions and victims, though permissive parents were least likely to anticipate prompting apologies. Parents endorsed different reasons for prompting apologies as a function of transgression type, suggesting that they attend to key features of their children’s transgressions when deciding when to prompt apologies.

Keywords: parenting, apology, socialization, moral development, social domain theory

Conflict and transgression are recurrent elements in young children’ social interactions (Alink et al., 2006; Nagin & Tremblay, 1999; Ross & Conant, 1992). Yet children’s conflicts can have positive outcomes (Hartup, 1992); children who are clear and friendly in their conflict-related communication are viewed as likable (Gottman & Graziano, 1983). It is not surprising, then, that adults sometimes use children’s conflicts and transgressions as opportunities for teaching children rules and empathy (Lopez, Schneider & Dula, 2002; Wang, Bernas & Eberhard, 2008). One prosocial approach to resolving conflicts is the use of an apology (Anderson, Linden, & Habra, 2006; Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Lazare, 2004; McCullough et al., 1998; Ohbuchi, Kameda, & Agarie, 1989). In the present study, we investigated how adults use apology prompts in the wake of children’s transgressions to highlight social rules and to teach social skills.

Apology Prompting by Parents

Aggressive, coercive, and “tattling” behaviors are associated with peer rejection, whereas behaviors that promote reconciliation are associated with acceptance (Bryant, 1992; Chung & Asher, 1996; Putallaz & Sheppard, 1990). Hence, apologizing may be a strategy that parents teach in order highlight social rules and promote social success. Among adults, apologizing is effective in reducing retaliation and engendering forgiveness (e.g., Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Lazare, 2004; Ohbuchi, Kameda, & Agarie, 1989). Children as young as age four also view apologetic transgressors as nicer and more remorseful than unapologetic transgressors (Smith, Chen, & Harris, 2010; Smith & Harris, 2012; Vaish, Carpenter, & Tomasello, 2011). Thus, the apology prompt is an important socialization tool that adults are likely to use with children following a transgression.

Two recent home-based studies have examined this topic. Schleien, Ross, and Ross (2009) noted the type of apologies produced (prompted vs. unprompted) between siblings at ages 2–4 and then two years later. Thirty-eight percent of children’s observed apologies were prompted, and spontaneous apologizing had increased by the later time point. Ely and Gleason (2006) found that 1–6-year-old children were exposed to talk about apologies via both prompting and apologies directed at them by parents. A sizable minority of children’s apology statements (28%) followed parental prompting, and prompts elicited considerable compliance (87%). Ely and Gleason found that apology prompts declined after age 4 years; however, their samples of parent-child discourse were drawn from relatively tranquil moments. Given the relatively high rates of conflict and aggression in early childhood (Alink et al., 2006; Ross & Conant, 1992), the finding that prompts and apologies are on the decline after age three may not hold for other settings.

The present study gathered systematic data on parental apology prompting, using social domain theory as a guide (Smetana, Jambon, & Ball, 2014; Smetana, 2006; Turiel, 1983). According to social domain theory, young children and adults view the social world as consisting of distinct domains of social rules and knowledge. The present study focused on the moral and social-conventional domains.

The social-conventional domain is characterized by rules that are informed by social norms (e.g., eating pie without a utensil may be viewed as a breach of convention, but can be considered acceptable in some contexts, such as in a pie-eating contest). The moral domain, by contrast, is characterized by rules related to welfare, justice, and rights (Jambon, & Ball, 2014; Smetana 2006; Turiel, 1983). Children across a diverse array of cultures reliably distinguish between these domains in the preschool years by asserting, for example, that moral, but not conventional norms, are context-independent and impose obligations regardless of whether an authority figure has endorsed them (Turiel, 2006). For example, a moral violation such as using provocative aggression is seen as wrong, even if there is no explicit rule forbidding this, whereas a conventional violation such as calling a teacher by a first name may not be seen as wrong in some contexts.

Of particular importance to the present study, parents also talk to their children about moral and social-conventional rules differently, and address moral violations in a more consistent manner (Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana, 1981, 1997, 2006; Smetana, Kochanska, & Chuang, 2000). Mothers also justify the rules they have for their children in different ways, depending on the domain in which the rule falls, with moral justifications being common when reasoning about the enforcement of interpersonal rules, but not when reasoning about conventional rules (Smetana et al., 2000). Given the oftentimes more serious nature of moral violations, and the fact that parental responses to children’s social breaches place particular emphasis on moral transgression, we predicted that parents would report a greater likelihood of prompting an apology following moral compared to conventional transgressions.

Research on social and moral development has also documented the importance that both children and adults place on the intentionality of a transgressor, particularly in instances of moral transgression (Cushman, 2008; Killen et al., 2011; Killen & Rizzo, 2014; Young et al., 2007; Zelazo, Helwig, & Lau, 1996). For example, Killen and colleagues (2011) found that children’s evaluations of a transgression in the moral domain were dependent upon whether they viewed the transgression to be accidental or intentional. As such, we investigated whether parents are sensitive to this issue as they respond to their children’s morally-relevant transgression by investigating whether they prompt apologies on the basis of their children’s intentions, or out of concern for the effects of a moral transgression. If parents focus on intentions, apology prompting rates should be relatively low in response to children’s accidental moral transgressions (e.g., accidentally hurting another child) compared to their intentional moral transgressions (e.g., hurting another child on purpose). However, if apology prompts are tied to the ultimate effects of transgression, parental apology prompting rates should be similar across intentional and accidental transgressions. This possibility would reflect an “outcome bias,” which has been documented in young children (e.g., Sato & Wakebe, 2014), who are prone to focus on the outcomes of a transgression without incorporating the intention of the transgressor into their evaluations.

We also asked parents to consider scenarios in which their children transgressed against (a) the parents themselves, and (b) their children’s peers. Parents place a great deal of value on their children’s interpersonal development (Quirk, 1984), and they consistently rate longer-term child socialization goals as important across a variety of social situations (as opposed to being focused on more immediate parent-focused goals such as getting a child to obey; Hastings & Grusec, 1998). In fact, socialization goals were rated as especially important in the context of a child committing an interpersonal breach, such as using derogatory language to talk about other people (Hastings & Grusec, 1998). Thus, we hypothesized that parents in the present study would have a particular concern for ensuring that their children apologized in situations likely to affect a child’s level of social acceptance. We predicted that parents would report more apology prompting in the peer-as-victim scenarios, where social acceptance is more relevant. It is possible, however, that parents use children’s transgressions against parents as “teachable moments” for socializing apology use.

Lastly, we tested hypotheses concerning authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles (Baumrind, 1973; 1996). Authoritative parents are relatively high in warmth/responsiveness and demandingness, establishing clear behavioral standards while showing care and a willingness to consider children’s perspectives. Authoritarian parents are relatively low in warmth/responsiveness and high in demandingness, expecting compliance and sometimes using threats and punishment to ensure it. Given that these two parenting styles both involve a high degree of demandingness, we predicted that authoritarian and authoritative parents would be more likely to prompt apologies compared to those reporting a relatively permissive style. Permissive parents have been found to be relatively low in demandingness and high in warmth/responsiveness, a finding that further informs our hypothesis. Our hypothesis is also consistent with Smetana (1995b), who found that, compared to permissive parents, authoritarian and authoritative parents were more likely to judge a wide range of acts committed by children to be subject to parental authority (these included acts in the moral and conventional domains). Nevertheless, we anticipated that all three groups of parents would be sensitive to the manipulation of transgression types in responding to the survey questions. This prediction fits with findings that some situational factors exert powerful influences on most parents, no matter what their parenting style is (e.g., Critchley & Sanson, 2006; Grusec & Kuczynski, 1980).

Method

Participants

Parents of 3–10-year-old children participated via an online questionnaire (all aspects of the procedure were approved by the Harvard University IRB). Parents of children in this age range were chosen because social behaviors warranting apology prompts (e.g., coercion during conflict, instrumental aggression, verbal aggression) are relatively common during early to middle childhood (e.g., Abuhatoum & Howe, 2013; Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006; Laursen, Finkelstein, & Townsend-Betts, 2001; Laursen, Hartup, & Koplas, 1996). Parents were contacted via online discussion groups focused on parenting and education (groups were hosted by Yahoo, Google, and Findsmithgroups). Invitations to participate were sent to group administrators, who then posted the messages to the groups. Groups from rural and urban settings across the United States were contacted, as were groups focused on parenting in racial/ethnic minority families and parenting by fathers. Eighty-four groups were contacted and approximately one third of group administrators responded. Parents were told that participation would give them the chance to win one of four $50 Target gift cards. The final sample (n = 483) was comprised of 400 mothers and 83 fathers. Twenty-nine percent of both mothers and fathers had completed a college degree. However, there were differences between mothers and fathers with regard to the highest level of education (χ2(2, N = 482) = 14.84, p < .001), with fathers (26%) being more likely than mothers (11%) to have not received a college degree, and with mothers (60%) being more likely than fathers (45%) to have engaged in some level of graduate school work.

Parents were asked to focus on one of their children between the ages of 3–10. This ensured that, regardless of how many children parents had, each parent was thinking about a single child. The mean age of the focal children was 5.90 (SD = 2.14; 57% were boys). Fifty-seven percent of the focal children were preschool aged (i.e., 3–5 years), and 43% were 6–10 years of age; child age did not differ as a function gender, t(481) = −.34, p = .74. Parents were asked to identify the racial/ethnic background of the focal children; 72.3% were European-American; 20.2% were multiracial; 3.3% were African-American; 2.5% were Asian-American; 1% were Latino/a. The birth order of the focal children was also probed: 28% were only children; 48% were first-borns; 24% were born second or later.

Measures

Crowne-Marlowe Social Desirability Scale (SDS)

Thirty-three items were adapted from the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1960), a measure of the extent to which people project unreasonably favorable impressions of themselves. Because asking parents about their parenting practices is likely to elicit socially-desirable responding, this scale was used as a control variable. Each item was answered as either true or false (e.g., No matter who I’m talking to, I’m always a good listener). Internal consistency was good (α = .79); responses were summed to form a scale with a possible range of 0–33, with higher values indicating a greater desire to present a favorable impression.

Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ)

Thirty items were adapted from the Parent Authority Questionnaire (Buri, 1991) to measure parenting style. There were ten authoritative items (e.g., I direct the activities and decisions of my children through reasoning and discipline), ten authoritarian items (e.g., I do not allow my children to question any decisions I have made), and ten permissive items (e.g., Most of the time, I do what my children want when making family decisions). Parents used a 5-point scale to indicate the extent to which they agreed (the scale ranged from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’). The original items were worded about the parents of respondents; we altered items such that respondents were asked to rate their own parenting behaviors. Cronbach’s alphas for the subscales were good: authoritative = .68; authoritarian = .84; permissive = .72.

Prompting frequency scale

We created an 18-item scale to measure the frequency of anticipated apology prompting behavior (see Appendix A). Parents were asked to imagine their children committing specific intentional moral, accidental moral, and social-conventional transgressions and to say how often they would prompt an apology using a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The items were composed of equal numbers of transgression types, and within each type of transgression half of the items described peer victims and the other half described the parents themselves as the victims. Sample items include: “Your child interrupts you or another adult during a conversation” (conventional/parent victim); “Your child yells at or teases another child” (intentional moral/peer victim); and “Your child accidentally breaks another child’s toy while playing with it” (accidental moral/peer victim). Internal consistencies for all six subscales were good (αs ranged from .71 to .80).

Apology importance and justification measure

Given its apparent importance as a socialization tool, we also examined how parents justified their use of apology prompting. Toward this end we first asked parents to think about their child committing a transgression in three scenarios in which the victim identity was unspecified: (1) intentional moral (hurting or upsetting another person on purpose), (2) accidental moral (hurting or upsetting someone by mistake), and (3) conventional (breaking a rule during a game). Parents rated how important it would be for their child to learn to apologize after each type of transgression on a scale ranging from 1 (highly unimportant) to 5 (highly important).

Parents who indicated that learning to apologize would be important to some degree were directed to choose among a set of nine justifications that were predetermined on the basis of pilot testing with a group of 63 parents of 5–9-year-old children (see Appendix A for the list of justifications and Appendix B for additional information about the pilot sample). Examples include: My child needs to understand other people’s feelings - apologies help with this and My child needs to acknowledge that they did something wrong. Parents who did not indicate that learning to apologize would be important were directed to a different set of predetermined justifications. Examples include: I want my child to learn his or her own way of solving problems and I would rather see my child make amends through actions, not words. Parents were able to endorse multiple justifications (i.e., they were not limited to one).

In the comments section of the survey, 21 parents indicated that they mistakenly indicated ‘unimportant’ when asked about apologies following moral transgressions. The ratings for these parents were changed to reflect their expressed intentions (which were either ‘important’ or ‘highly important’). Justification data for these parents are missing because these participants were directed to the wrong set of justification choices.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for the study variables are displayed in Table 1. Consistent with our hypotheses, parents anticipated prompting apologies quite often following intentional moral transgressions, and less often following conventional transgressions. Further, parents attached importance to children’s apologies following accidental moral transgressions against peers.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritative Parenting | 4.15 | 0.35 | 3.10 | 5.00 |

| Authoritarian Parenting | 2.96 | 0.50 | 1.45 | 4.50 |

| Permissive Parenting | 2.15 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 3.60 |

| Social Desirability | 17.02 | 5.20 | 0.00 | 29.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Intentional Moral - Child Victim | 4.53 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Intentional Moral - Parent Victim | 4.03 | 1.06 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Accidental Moral - Child Victim | 4.20 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Accidental Moral - Parent Victim | 3.04 | 1.09 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Conventional - Child Victim | 3.14 | 1.16 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Anticipated Apology Prompt Freq.: Conventional - Parent Victim | 2.54 | 1.07 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Importance of Child Apology After Intentional Moral Transgression | 4.63 | 0.67 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Importance of Child Apology After Accidental Moral Transgression | 4.18 | 0.77 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Importance of Child Apology After Conventional Transgression | 3.46 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

Note. Possible range for social desirability: 1–33; possible range for all other variables: 1–5.

Cluster Analysis of Parenting Style

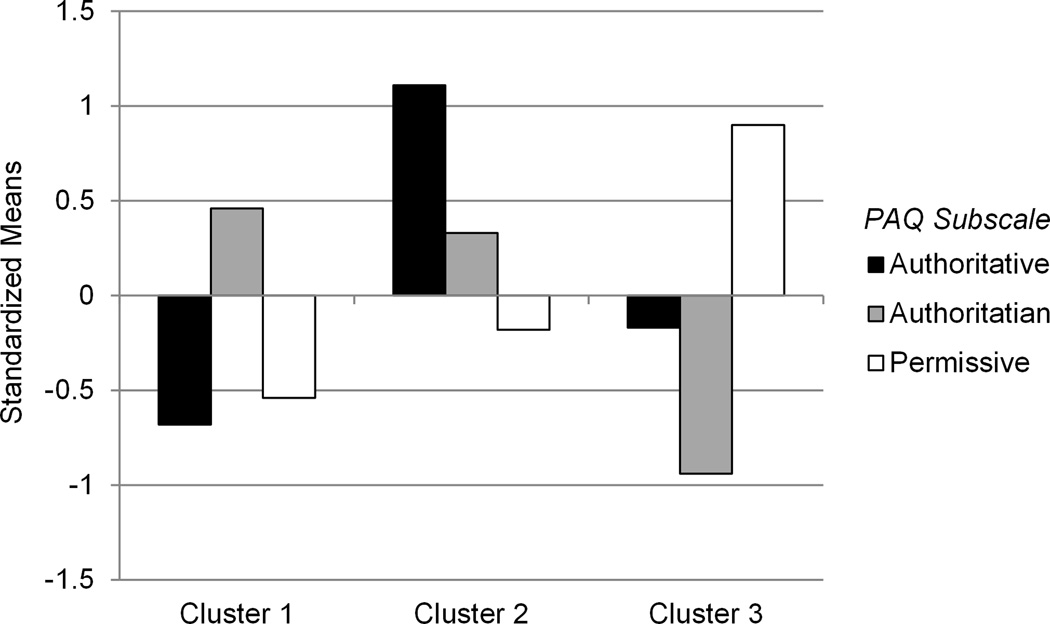

To consolidate the parenting style data, the authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting variables were standardized and subjected to a K-means cluster analysis5, with three clusters specified a priori. One cluster of parents was above the mean on the authoritarian scale and below the means on the authoritative and permissive scales; this group was identifiable as being relatively authoritarian (n = 196; Cluster 1 in Figure 1). Another cluster was high on the authoritative scale and near the mean on the authoritarian and permissive scales; this group was identifiable as being relatively authoritative, (n = 141; Cluster 2 in Figure 1). A third cluster was high on the permissive scale and was low on the other two scales; this group was identifiable as being relatively permissive (n = 146; Cluster 3 in Figure 1). The resulting categories constituted the parenting style variable used in the analyses reported below.

Figure 1.

Standardized Mean Scores on the Parental Authority Questionnaire Subscales as a Function of Cluster Profile

Multivariate Analyses of Apology Prompt Frequency

The apology-prompt frequency data were initially analyzed with a 3 (parenting style) × 3 (transgression type) × 2 (victim type) × 2 (parent gender) × 2 (child gender) mixed-measures ANCOVA, with child age, parent level of education, child birth order, and parent social desirability bias included as covariates.

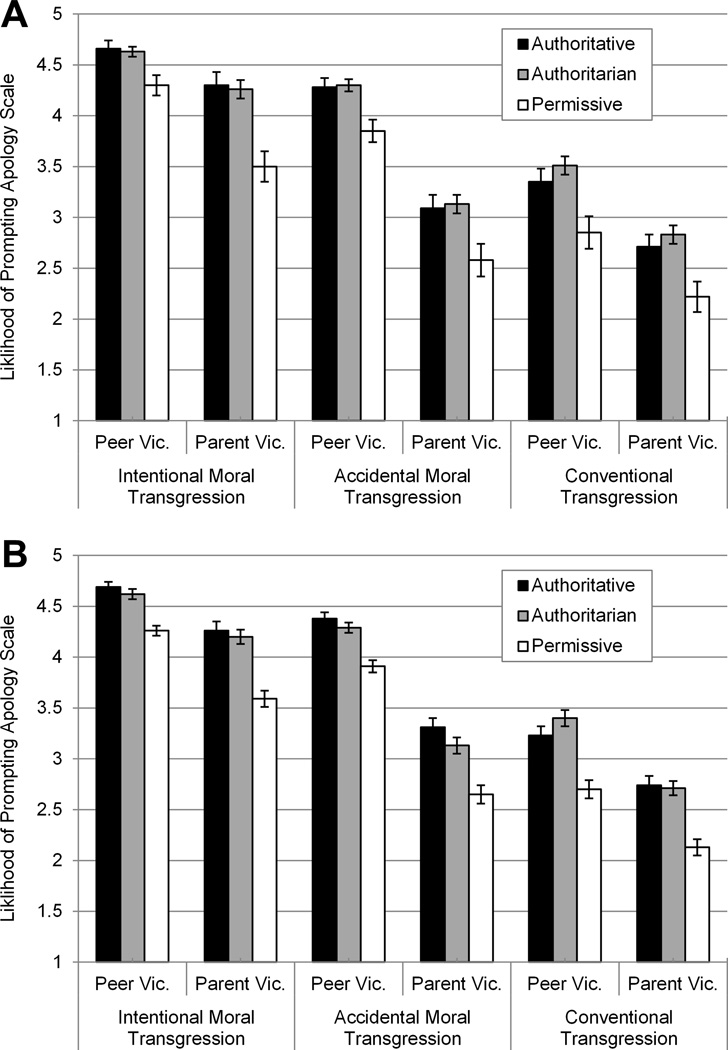

Given the large sample size, very small main and interaction effects emerged as significant. To simplify analysis and interpretation, we retained variables whose main or interaction effects had effect sizes (partial eta-squared) of .03 or larger6. As a result, child age, child gender, parent gender, child birth order, and parent education level were all eliminated from the analysis. This resulted in a parsimonious 3 (parenting style) × 3 (transgression type) × 2 (victim type) mixed-measures ANCOVA, with social desirability bias as a covariate. We present the results of the full model in Figure 2a (controlling for parent and child gender, child age, parent education, child birth order, and respondents’ social desirability bias), and we present the results of the more parsimonious model in Figure 2b (controlling for social desirability bias). Below, we focus on the model presented in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

a and b. Mean Scores on Apology Prompt Likelihood Scale as a Function of Transgression Type, Victim Type, and Parenting Style (The model in Figure 2a controls for parent and child gender, child age, parent education, child birth order, and respondents’ social desirability bias; the more parsimonious model in Figure 2b controls for social desirability bias.)

There was a main effect of parenting style, F(2, 479) = 28.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .11, which was clarified with Bonferroni-corrected t-tests using the mean likelihood of prompting apology (across all scenarios) as the dependent variable. As is evident in Figure 2b, permissive parents were significantly less likely to prompt apologies than were authoritative parents (t(285) = 6.84, p < .001) and authoritarian parents (t(340) = 6.68, p < .001). The authoritative and authoritarians groups did not differ from each other, p = .58. A main effect of social desirability bias also emerged, F(1, 479) = 31.03, p < .01, ηp2 = .02. Given that social desirability bias was included as a control variable, it is not explored in depth here or elsewhere.

There were also main effects of transgression type, F(2, 958) = 97.78, p < .001, ηp2 = .17 and victim type, F(1, 958) = 78.16, p < .001, ηp2 = .14, and there was a significant Transgression type × Victim type interaction, F(2, 958) = 7.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .02. As seen in Figure 2b, the different parenting groups responded similarly to the transgression and victim type manipulations. Thus, the data were pooled across the three parenting styles, and the Transgression type × Victim type interaction displayed in Figure 3 was clarified using Bonferroni-corrected comparisons.

Figure 3.

Mean Scores on Apology Prompt Likelihood Scale as a Function of Transgression Type and Victim Type

When the child’s peers were described as the victims, parents anticipated prompting apologies most often after intentional moral transgressions (M = 4.53), and this was followed closely by -- but was significantly different from -- anticipated prompting for accidental moral transgressions (M = 4.20), t(482) = 10.82, p < .001. These two means were followed more distantly (M = 3.14) by anticipated prompting for conventional transgressions against peers (for difference with intentional moral, t(482) = 30.39, p < .001; for difference with accidental moral, t(482) = 21.00, p < .001).

Similarly, when the parents themselves were described as the victims, parents anticipated prompting apologies most often after intentional moral transgressions (M = 4.03). This differed from anticipated prompting for accidental moral transgressions against parents (M = 3.04; t(482) = 19.82, p < .001), and from anticipated prompting for conventional transgressions against parents (M = 2.54; t(482) = 33.20, p < .001). The difference between the likelihood of prompting an apology for accidental moral versus conventional transgressions against parents also differed significantly, t(482) = 10.08, p < .001.

For all transgression types, parents anticipated more apology prompting when peers were victims rather than parents: intentional moral (Mdiff = .50; t(482) = 13.44, p < .001), accidental moral (Mdiff = 1.16; t(482) = 26.14, p < .001), and conventional (Mdiff = .60; t(482) = 16.12, p < .001). However, the differentiation between peers and parents was especially marked for accidental moral transgressions, forming the basis of the significant Transgression type × Victim type interaction.

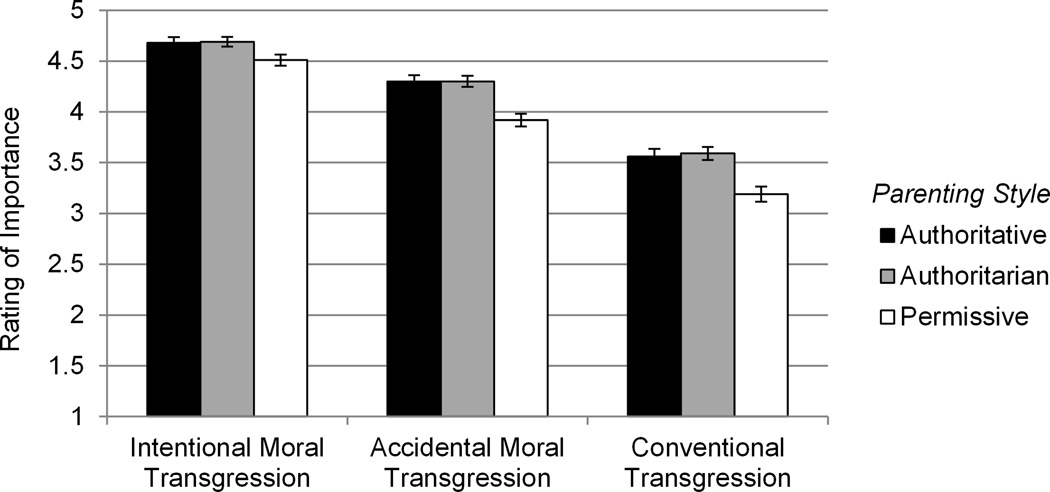

Parents’ Justifications for Prompting Apologies

Parental responses to the first part of the justification questions -- ratings of apology importance -- were analyzed with a 3 (transgression type) × 3 (parenting style) mixed-measures ANCOVA, controlling for social desirability. As seen in Figure 4, there was a main effect of transgression type, F(2, 958) = 49.90, p < .001, ηp2 = .09. Post-hoc contrasts using the Bonferroni correction indicated that parents rated children’s learning to apologize following intentional moral transgressions as most important (M = 4.63), and this was followed by -- and was significantly different from -- the importance rating for accidental moral transgressions (M = 4.18), t(482) = 11.47, p < .001. The mean importance rating for children learning to apologize after a conventional transgression (M = 3.46) was significantly lower than the important ratings for both intentional moral (t(482) = 24.66, p < .001) and accidental moral (t(482) = 15.03, p < .001) transgressions.

Figure 4.

Mean Rating of Apology Importance as a Function of Transgression Type and Parenting Style

There was also a main effect of parenting style, F(2, 479) = 17.86, p = < .001, ηp2 = .07. Post-hoc contrasts using the Bonferroni correction indicated that the authoritarian (M = 4.19) and authoritative (M = 4.18) parents did not differ in their overall ratings of apology importance (p = .84). Both the authoritarian group (t(340) = 5.84, p < .001) and the authoritative group (t(285) = 4.93, p < .001) rated apologies as more important than did permissive parents (M = 3.87). The Transgression type × Parenting style interaction was not significant (p = .20).

Justifying importance of apology following intentional moral transgressions

Only 18 parents (4%) indicated that it was not important for their children to learn to apologize following an intentional moral transgression. Thus, only the justifications from parents whose responses fell in the important range of the response scale were analyzed. A series of nine one-way ANOVAs was used to compare parents’ responses to each of the nine supplied justifications (coded as 1 = endorsed, 0 = not endorsed)7 as a function of parenting style. In order to control for type I error, post hoc Tukey tests were only used to clarify initial contrasts that were significant at p < .005.

The percentages of parents who endorsed the nine justifications are presented in Table 2. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parents justified their importance ratings concerning intentional moral transgression in similar fashion, with frequent endorsement of items related to taking responsibility, increasing interpersonal understanding, and teaching that harming others is not acceptable. The parenting groups differed on the following three items that are listed under the Intentional Moral heading in Table 2. First, for the statement that apologies are important for taking responsibility, 88% of authoritarian and 90% of authoritative parents agreed (difference not significant), in contrast with 74% of permissive parents (the latter group differed from the first two groups; p-values = .004 and .002, respectively). Second, for the statement that apologies help children admit wrongdoing, 77% of authoritarian, 68% of authoritative, and 56% of permissive parents agreed; the difference between the authoritarian and permissive parents was significant, p < .001, and the authoritative group did not differ significantly from the other two groups. Finally, for the statement that children need to know when to say “I’m sorry,” 37% of authoritarian, 36% of authoritative, and 20% of permissive parents agreed; the permissive group differed significantly from the authoritarian and authoritative groups, p-values = .005 and .02, respectively.

Table 2.

Percentages of parents endorsing supplied justifications for why learning to apologize is important

| Transgression type → | Intentional Moral |

Accidental Moral |

Conventional |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting category → % rating apologies as important → |

AV 96% |

AN 97% |

P 95% |

AV 93% |

AN 91% |

P 79% |

AV 59% |

AN 56% |

P 35% |

| Learning to apologize is important because… | (statistics below include only those parents who rated apologies as important) | ||||||||

| Apologies are part of taking responsibility | 90%a | 88%a | 74%b | 71% | 63% | 59% | 77% | 73% | 78% |

| Apologies help children understand others | 85% | 80% | 76% | 85% | 85% | 78% | 40% | 35% | 24% |

| Apologies teach that harming others not okay | 80% | 83% | 77% | 63% | 66% | 55% | 42% | 36% | 22% |

| Apologies help children admit wrongdoing | 68%a | 77%b | 56%a | 46% | 38% | 33% | 78% | 72% | 59% |

| Apologies make other people feel better | 61% | 50% | 50% | 65% | 63% | 57% | 19% | 22% | 14% |

| Apologies help to clear things up | 40% | 46% | 36% | 53% | 44% | 44% | 40% | 35% | 25% |

| Apologies promote learning about fairness | 32% | 29% | 22% | 17% | 13% | 7% | 75% | 80% | 76% |

| Children need to know when to apologize | 36%a | 37%a | 20%b | 32%a | 33%a | 16%b | 31% | 28% | 22% |

| I look bad if my child doesn’t give one | 12% | 16% | 18% | 5% | 6% | 10% | 7% | 4% | 6% |

Note. AV = authoritative. AN = authoritarian. P = permissive. Parenting groups were compared on each item within transgression types (i.e., tests were not carried out across transgression types).

Differing letters above percentages indicate significant Tukey test differences at p < .05 (initial ANOVAs were conducted with alphas set at .005).

Justifying the importance of apology following accidental moral transgressions

Consistent with the results for the intentional moral transgressions, a large majority of parents (88%) reported that learning to apologize following an accidental moral transgression is important for children. As such, only the justifications attached to ratings of importance were formally analyzed (see Table 2). As was true above, the three parenting groups endorsed the justifications at very similar rates. Items that received strong endorsements in the context of an accidental transgression were: taking responsibility, increasing interpersonal understanding, teaching that harming others is not acceptable, and making other people feel better. One significant group difference did emerge; for the statement that children need to know when to say “I’m sorry,” 33% of authoritarian, 32% of authoritative, and 16% of permissive parents agreed; the permissive group differed significantly from the authoritarian and authoritative groups, p-values = .005 and .02, respectively.

Justifying importance of apology following conventional transgressions

Fewer respondents (50%) indicated that it was important for their children to learn to apologize following a conventional transgression. The justifications endorsed by the parents who indicated that it was important were analyzed first and are presented in Table 2.

Again, the authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parents endorsed the justifications with similar frequency. Parents were especially likely to endorse the ideas that apologies following conventional transgressions help children take responsibility for their actions, help them admit wrongdoing, and promote learning about fairness. Using the criterion that post hoc contrasts would be conducted only if an omnibus p-value was less than .005, none of the justifications for the importance of apologies following conventional transgressions were subjected to further analysis.

Fifty percent of parents indicated learning to apologize after conventional transgressions was not important for children; there was only moderate endorsement of most of the supplied justifications for this viewpoint (see Table 3). Here again, using the criterion that post hoc contrasts would be conducted only if an omnibus p-value was less than .005, none of the justifications for lack of importance of post-conventional-transgression apologies were subjected to further analysis.

Table 3.

Percentages of parents endorsing supplied justifications for why learning to apologize is not important

| Transgression type → | Intentional Moral |

Accidental Moral |

Conventional |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting category → % rating apologies as not important → |

AV 4% |

AN 3% |

P 5% |

AV 7% |

AN 9% |

P 21% |

AV 41% |

AN 44% |

P 65% |

| Learning apology isn’t important because… | (statistics below include only those parents who rated apologies as not important) | ||||||||

| For amends, actions better than words | 67% | 60% | 57% | 40% | 24% | 53% | 38% | 38% | 44% |

| Adults should let kids work it out | 0% | 20% | 29% | 20% | 18% | 33% | 41% | 36% | 56% |

| I want child to solve problems in own way | 17% | 40% | 29% | 30% | 12% | 40% | 40% | 34% | 36% |

| It’s kids being kids; no big deal | 0% | 20% | 0% | 20% | 12% | 10% | 31% | 29% | 33% |

| Caring is important, but apologies not vital | 33% | 0% | 57% | 10% | 35% | 47% | 12% | 3% | 15% |

| Apologies aren’t effective; they’re just words | 33% | 20% | 71% | 0% | 0% | 20% | 3% | 2% | 12% |

| My focus would be more on punishing child | 17% | 20% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 3% | 1% | 1% |

| No one was hurt in this scenario | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 29% | 22% | 23% |

| It was a mistake; no apology necessary | N/A | N/A | N/A | 40% | 35% | 37% | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Note. AV = authoritative. AN = authoritarian. P = permissive. Parenting groups were formally compared on each item within the conventional transgression type only, due to low-frequency responding in the other transgression types. Comparisons were not carried out across transgression types. Initial ANOVAs were conducted with alphas set at .005, and none of the omnibus p-values was < .005 (thus, post hoc analyses were not conducted for the Conventional scenario).

Differences in justifications across transgression types

The responses of parents (nauthoritative = 78; nauthoritarian = 100; npermissive = 47) who indicated that learning to apologize was important in all three scenarios were analyzed with the goal of exploring differences across transgression type. In an effort to maximize cell sizes, and because the parenting groups were quite similar in their justification endorsements, data were pooled across parenting styles8.

For each justification related to the importance of learning to apologize, a repeated-measures ANOVA with transgression type as a within-subjects factor was used; post hoc analyses were used to clarify significant F-tests (see Table 4 for results).

Table 4.

Percentages of parents endorsing supplied justifications for why learning to apologize is important (among subgroup of parents who consistently rated children’s apologies as important)

| Transgression type | Intentional Moral | Accidental Moral | Conventional |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning to apologize is important because… | (table includes parents who rated apologies as important in all scenarios) | ||

| Apologies are part of taking responsibility | 86%a | 65%c | 76%b |

| Apologies help children understand others | 86%a | 87%a | 30%b |

| Apologies teach that harming others not okay | 82%a | 62%c | 33%b |

| Apologies help children admit wrongdoing | 76%a | 39%b | 73%a |

| Apologies make other people feel better | 54%a | 64%c | 18%b |

| Apologies help to clear things up | 51%a | 50%a | 36%b |

| Apologies promote learning about fairness | 36%a | 15%c | 79%b |

| Children need to know when to apologize | 35%a | 31%ab | 27%b |

| I look bad if my child doesn’t give one | 15%a | 8%b | 6%b |

Note. The parents represented in Table 4 are only those parents who rated children’s apologies as important across all three transgression types.

Differing letters above percentages indicate significant Bonferroni tests (conducted only after initial ANOVAs were significant with alphas set at .005).

All F-tests were significant with alpha set at .005. The general trends are summarized here, and the results are presented in Table 4. The most commonly-endorsed justifications for intentional moral transgressions and accidental moral transgressions were similar (numbers 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6) with one exception, namely My child needs to acknowledge that they did something wrong - apologies can accomplish this, which was viewed by parents as less relevant to accidents. The top selections above 50% for the two types of moral transgressions were: My child needs to take responsibility for what he or she did - the act of apologizing is part of this, My child needs to understand other people’s feelings - apologies help with this, I want my child to know that hurting or upsetting others is not okay, My child needs to help the other person feel better - apologies can help others feel better, and Apologies help to clear things up - so that the other person understands what happened.

The pattern of justifications was different for conventional transgressions, with numbers 1, 4 and 7 being the three endorsed by more than half of the parents. These items were: My child needs to take responsibility for what he or she did - the act of apologizing is part of this, My child needs to acknowledge that they did something wrong - apologies can accomplish this, and My child needs to learn what’s fair and what’s not - learning to apologize is a part of this. Thus, after a conventional transgression, apologies were viewed as most helpful in admitting wrongdoing and establishing fairness, whereas apologies following moral transgressions, whether intentional or accidental, were often viewed as useful in promoting responsibility, interpersonal understanding, and reparation.

Discussion

Most parents endorsed the importance of their children learning to apologize, and very few parents dismissed apologies as empty words. Further, consistent with research on social domain theory, parents differed in their responses to moral and conventional transgressions; parents viewed apologies as especially important following intentional and accidental moral transgressions, and less important following conventional transgressions. Their justifications for the importance of children’s apologies revealed a similar pattern for intentional and accidental moral transgressions as distinct from conventional transgressions, as did the frequencies with which they anticipated prompting apologies. Thus, although parents might conceivably have viewed accidental moral transgressions as considerably less connected to the need for apology compared to intentional moral transgressions, this was not the case across three different measures. With regard to how they manage children’s morally-relevant violations, then, parents show a marked sensitivity to the distinction between moral and conventional transgressions, whereas the distinction between intentional and accidental moral transgressions is much less pronounced. The present data from parents of 3–10-year-olds fit with recent studies showing that adults exhibit an ‘outcome bias’ in some situations when assessing how wrongdoers should be treated (e.g., Cushman, Dreber, Wang, & Costa, 2009; Oswald, Orth, Aeberhard, & Schneider, 2005).

In the case of their own children’s transgressions, this outcome bias appears to be connected to a desire to teach their children how to manage potentially ambiguous and damaging social situations. This fits with the fact that parents especially anticipated prompting apologies following accidental moral transgressions when they involved children’s peers as victims. In the accidental peer-victim context, parents likely recognize that some peer victims may not grasp the lack of intentionality. This possibility is supported by the moderately elevated use of the, “Apologies help to clear things up” justification for the accidental moral transgression, compared to the intentional moral transgression. Although the parent-vs.-peer victim distinction was most marked in the case of accidental moral transgressions, a similar pattern of responses was found for the other transgression types. This provides support for our view that parents are especially likely to use apology-prompts as a means of teaching their children tools to effectively resolve peer conflicts.

In addition to the robust pattern of results involving the intentional and accidental moral transgressions, the present data also show that parents are quite sensitive to the moral/conventional distinction and effectively mark that distinction - in this case via apology prompts - for their children. This is consistent with other studies on social domain theory, which have found that parents mark the distinctions between social domains by using different types of reactions to different types of transgressions (e.g., Dahl & Campos, 2013). These results extend previous work by demonstrating how post-transgression reactions also differ for moral and conventional transgressions.

While the present study investigated the role of intentionality for parental responses to moral transgressions, future research should investigate how parents respond to intentional and accidental conventional transgressions. Paralleling our findings related to moral transgressions, parents may respond to intentional and accidental conventional transgressions in a similar manner, with a focus on the outcome of the transgression. However, it is also possible that parents would view intentional conventional transgressions as more serious than accidental conventional transgressions.

Parents’ differentiation between the three types of transgressions was apparent in their endorsements of justifications for the importance of apology. In the context of intentional moral transgressions, parents viewed apology prompts as important for: helping children to take responsibility, promoting perspective taking, teaching about harm, improving others’ feelings, helping children admit wrongdoing, making others feel better, and clearing things up. A similar pattern of endorsement was found for accidental moral transgressions with one important but understandable exception: parents rarely viewed post-accident apologies as useful for admitting wrongdoing. The pattern of justification endorsement for conventional breaches was qualitatively different, with a focus on helping children to take responsibility, helping children admit wrongdoing, and promoting learning about fairness. These findings are again consistent with research on social domain theory, which argues that individuals are particularly concerned with the harm to the victim due to a moral transgression, and are more concerned with the threats to group functioning and group identity following conventional transgressions (Smetana, Jambon, & Ball, 2014).

An additional focus of this study was parenting style. Permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian parents were similarly flexible in their responding across victim and transgression types. Thus, the present study adds to the literature showing that parental approaches to discipline are influenced both by stable parent-level variables but also by context (e.g., Critchley & Sanson, 2006; Grusec & Kuczynski, 1980; Holden & Miller, 1999). Further, among parents who viewed apologies as important tools for their children, all three groups of parents had remarkably similar views on why apologies were important.

Nevertheless, differences between permissive and non-permissive parenting styles did emerge. Consistent with our hypotheses, permissive parents were least likely to anticipate prompting an apology across all transgression and victim types, and the parents in the authoritative and authoritarian groups were virtually identical in their responding. The similarities between the authoritative and authoritarian groups are likely explained by the fact that both groups are high on the dimension of demandingness. Thus, both groups of parents may view the teaching of apology as a part of eliciting mature, responsible behavior from their children.

Although previous studies have noted that prompted apologies decline as children get older (e.g., Ely & Gleason, 2006), the present investigation did not reveal a negative association between child age and anticipated prompting frequency. This discrepancy is worth considering. In Schleien et al. (2010), prompting behaviors were logged after actual transgressions had been committed by children and witnessed by parents. Because with increasing age children get better at avoiding the gaze of authority figures when committing transgressions (Sutton, Smith, & Swettenham, 1999), naturalistic studies may tell us little about how parents view the importance and role of apology prompting with children across a wide age range. The present study asked parents whether they would prompt an apology if various transgressions had been committed by their children. The results show that parents are willing to prompt apologies from 3–10-year-old children, regardless of age, and view apology prompts as useful socialization tools.

There may be other factors contributing to the decreases in parental prompting behavior that are seen with increasing child age. In Ely and Gleason (2006), as apology prompts from parents declined in frequency with increasing child age, spontaneous apologies from children increased. Thus, while parents may continue to be at the ready with apology prompts, they may need to use them less frequently as children internalize apology scripts and come to understand their importance.

Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Although this study represents an important addition to this area of research, we acknowledge limitations and areas for future research. First, the sample was drawn from communities of highly educated parents who were motivated to discuss parenting issues. Such participants are not wholly representative of the full spectrum of U.S. parents; e.g., parental education is tightly linked to numerous aspects of parenting practices, including the quality and quantity of child-directed speech (Rowe, Ramani, & Pomerantz, in press). While lab- and home-based studies face similar sampling biases; future studies will advance this literature by enlisting more diverse samples of parents, to directly examine how parental education might influence apology prompting. Second, although the range of scenarios parents encountered was wider than what might be observed in a home-based study, it was still limited. For example, when parents rated whether apologies following an accident are important, they read a scenario about accidental harm. Although this item established that parents justify the importance of apology similarly across children’s accidentally and deliberately harmful acts, that pattern of justifications would likely have been different for non-harmful accidents. (Similarly, many parents would not have endorsed the fairness-related justification in response to the conventional transgression if that scenario had involved eating ice cream with one’s fingers.) Third, parents were asked to focus specifically on one of their children to ensure some degree of standardization. However, it is possible that some parents focused on their most, or least, troublesome child. Future research should investigate whether parents prompt apologies differently across multiple children.

A number of additional questions deserve attention. First, little is known about how children react to apology prompts. Although Schleien et al. (2010) showed that victims are sensitive to the spontaneity of apologies, there are a number of ways to interpret that finding. It could be that victims are sensitive to whether or not a transgressor independently thought to apologize, or it could be that, compared to prompted apologies, spontaneous apologies are more likely to be accompanied by genuine concern. Future research is needed to resolve this question.

A second area for future research is children’s use of apologies with peers. At present, the two studies of children’s real-world apologies (Ely & Gleason, 2006; Schleien et al., 2010) have involved home-based observations. Because peer relationships differ from children’s bonds with siblings and parents, it would be useful to know when and why children deploy apologies outside the family, and the extent to which these exchanges are effective. Importantly, such research would allow for an assessment of whether parenting practices predict children’s apologizing behavior outside the home.

Finally, we note that the present sample was comprised mostly of mothers (only 17% of the participants were fathers), and we did not find substantial effects of parent (or child) gender. Future research on this topic that utilizes a more balanced sample of mothers and fathers may uncover intriguing effects of parent gender, or patterns of behavior that differ as a function of parent by child gender.

Implications and Conclusions

Children as young as age four know that apologies can express remorse and alleviate a victim’s hurt feelings (Smith et al., 2010), and when young children are the target of a minor transgression, apologies have positive effects (Smith & Harris, 2012). Apologies are also linked to reconciliation in sibling conflicts (Schleien et al., 2010). Such findings show that young children appreciate the power of the very simple phrase: I’m sorry.

Children are prone to show concern for others from a young age (Zahn-Waxler, Radke-Yarrow, Wagner, & Chapman, 1992). While concerned behavior may be driven by the interplay of innate and socialized processes, the understanding and use of apology acts must be learned. The present results show that parents take the teaching of apology seriously. Given that even preschool-aged children understand a great deal about apologies, it is plausible that parents’ teaching promotes these early insights. The present study demonstrates parents’ role in prompting and promoting children’s apologies following a transgression.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parents who took part in this research. Work on this research by C.E.S was supported, in part, by Award Number T32HD007109 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. Work on this research by M.T.R. was supported by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pre-doctoral Traineeship (#T32HD007542).

Appendix A. Apology Prompting Questionnaire

NOTE TO READER: Directly after each of the 18 scenarios listed below, parents were asked about their children: “If he or she did not apologize, how likely would you be to ask/tell your child to apologize?” The scale used for the 18 items on this portion of the survey was: (1) I would never prompt an apology in this situation; (2) I would occasionally prompt an apology in this situation; (3) Probably about half the time; (4) I would prompt an apology most of the time in this situation; (5) I would always prompt an apology in this situation.

Instructions to Parents: On the next few pages, try to imagine that your child does each of the following things. Then, imagine that he or she does not apologize afterward. Think about how often you would prompt an apology from your child in each situation. There are no right or wrong answers here - we are simply interested in the range of answers parents provide.

| Item | Transgression Type |

Victim Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Imagine that your child hits or tries to hit another child on purpose |

Intentional Moral |

Peer |

| 2. Imagine that your child - without meaning to - says something that makes you feel bad |

Accidental Moral |

Parent |

| 3. Imagine that your child interrupts you and another adult during a conversation |

Social- Conventional |

Parent |

| 4. Imagine that your child accidentally drops a heavy toy on your foot, causing you a lot of pain |

Accidental Moral |

Parent |

| 5. Imagine that your child hits or tries to hit you after you enforce a rule |

Intentional Moral |

Parent |

| 6. Imagine that your child goes to the front of a line instead of waiting behind his/her friends |

Social- Conventional |

Peer |

| 7. Imagine that your child accidentally hurts another child by knocking them to the ground during a game |

Accidental Moral |

Peer |

| 8. Imagine that your child yells at or teases another child | Intentional Moral |

Peer |

| 9. Imagine that your child doesn’t complete a job or chore that you asked him or her to do |

Social- Conventional |

Parent |

| 10. Imagine that your child tries to hurt your feelings by saying something mean to you |

Intentional Moral |

Parent |

| 11. Imagine that your child accidentally damages something of yours (for example, a phone or wristwatch) by dropping it on the ground |

Accidental Moral |

Parent |

| 12. Imagine that your child breaks a rule in a game he or she is playing with another child |

Social- Conventional |

Peer |

| 13. Imagine that your child grabs or steals something from another child |

Intentional Moral |

Peer |

| 14. Imagine that your child accidentally breaks another child’s toy while playing with it |

Accidental Moral |

Peer |

| 15. Imagine that your child makes a mess when eating a meal, even after you’ve asked him or her to settle down |

Social- Conventional |

Parent |

| 16. Imagine that your child steals something that belongs to you in a sneaky way, without asking first |

Intentional Moral |

Parent |

| 17. Imagine that your child - without meaning to - says something that hurts the feelings of another child |

Accidental Moral |

Peer |

| 18. Imagine that your child quickly tears open all of his or her presents at a party without stopping to thank the kids who brought the gifts. |

Social- Conventional |

Peer |

Instructions to Parents: The next few pages ask a bit more about the importance you attach to your child learning to apologize in different situations.

How important is it to you that your child learns to apologize after he or she hurts or upsets another person on purpose? (Response scale: 1 = Highly unimportant; 3 = Neutral; 5 = Highly important)

How important is it to you that your child learns to apologize after he or she breaks a rule during a game? (Response scale: 1 = Highly unimportant; 3 = Neutral; 5 = Highly important)

How important is it to you that your child learns to apologize after he or she upsets or hurts someone by mistake? (Response scale: 1 = Highly unimportant; 3 = Neutral; 5 = Highly important)

NOTE TO READER: After parents responded to the first question about importance listed above, they were then asked to justify their responses. Parents who chose an answer in the important range (4 = important; 5 = highly important) were directed to the following set of justifications. They were allowed to choose any number of the provided justifications, ranging from zero to all.

My child needs to understand other people’s feelings - apologies help with this.

My child needs to acknowledge that they did something wrong - apologies can accomplish this.

I want my child to know that hurting or upsetting others is not okay.

My child needs to learn what’s fair and what’s not - learning to apologize is a part of this.

My child needs to take responsibility for what he or she did - the act of apologizing is part of this.

My child needs to help the other person feel better - apologies can help others feel better.

Apologies help to clear things up - so that the other person understands what happened.

It’s just important for my child to know when to say “I’m sorry.”

Honestly, it can make me look bad if my child doesn’t say “I’m sorry.”

Parents who chose an answer outside of the important range (3 = neutral; 2 = unimportant; 1 = highly unimportant) were directed to the following set of justifications. They were allowed to choose any number of the provided justifications, ranging from zero to all.

No one was hurt by this - so an apology isn’t important here. [NOTE: Only asked about the conventional transgression scenario.]

If it was a mistake, then an apology wouldn’t be necessary. [NOTE: Only asked about the accidental transgression scenario.]

I want my child to learn his or her own way of solving problems.

Kids will learn how to work things out for themselves - adults should let this happen.

I don’t think apologies are effective - they’re just words.

I would rather see my child make amends through actions, not words.

I want my child to learn how to care for others, but apologies aren’t a big part of this.

I would be more focused on punishing my child in this situation.

It’s just a situation where kids are being kids - it’s not a big deal.

After answering the first question about the importance of apology and making their justification choices, parents then repeated the same process for the other two questions about importance.

Appendix B. Information about Pilot Study

After rating the importance of apology in certain situations, parents in the present study were asked to justify their responses by selecting from among a set of supplied justifications. The justifications that we supplied were derived from a pilot study with 63 parents. Below we briefly describe the pilot procedure that produced the justifications that were in the present study.

Participants

Sixty-three parents of 5-9-year-old children (M = 6;11; range: 5;3 – 9;1) were recruited from elementary schools in the Boston area. The parents were predominantly white and middle-class, though a range of racial and socioeconomic groups was represented. Parents with more than one child were asked to respond to questions about only one of their children; the gender balance of the focal was roughly even (33 girls, 30 boys). The participating parents were almost entirely mothers.

Procedure

Via a paper-and-pencil survey, parents were asked about the importance (1 = not important; 2 = somewhat important; 3 = very important) they attached to their child learning to use an apology in three types of scenarios: an intentional moral transgression (upsetting someone on purpose), an accidental moral transgression that upset someone, and a conventional transgression (breaking a rule during a game). After each of the three scenarios, parents were asked to explain in their own words why children’s learning about apology might be important.

Scoring and Interrater Reliability

A grounded approach to coding was used, wherein the themes from the open-ended justifications parents provided were used to create coding categories. The coding categories that emerged involved parents writing about the importance of apologies in underscoring or teaching lessons in the areas of: (1) empathy or perspective taking; (2) awareness of moral rights and wrongs; (3) social-conventional rules; (4) taking responsibility/showing remorse; (5) caring for someone/making amends; (6) solving/clarifying problems or mistakes; (7) common courtesy or the pragmatics of apology (e.g., when/how to deliver an apology); and (8) issues of equity or fairness.

We also coded the justifications parents gave when they indicated that a child’s apology was not important in a given situation. These codes captured the following themes: (1) wanting children to discover their own conflict resolution tactics; (2) viewing apologies as ineffective; (3) viewing actual amends as being more important than words; (4) viewing punishment as more important than prompting apology; (5) believing that all children make social misteps and don’t need to apologize for most of them

Codes applied to each parental response were not mutually exclusive; some parental responses contained multiple themes (e.g., the view that apologies promote both caring behavior and empathy).

To assess interrater reliability, a second coder using the coding system to categorize 33% of the justification data. The second coder was trained on the coding system but was blind to the goals of the research. We computed Cohen’s kappa and/or percentage of agreement for each of the coded response categories across the three types of transgressions. (Computing kappa was not always possible, given the lack of variation in certain coded variables; e.g., the coders agreed that there was no mention of teaching conventional rules as parents discussed the importance of apology following a moral transgression.) All kappas were .70 or larger (the range was .70–1.00), and the agreement percentages were 91% or higher (the range was 91–100%). Where there was disagreement, differences were easily resolved through discussion.

Footnotes

We acknowledge that creating discrete groups of parents based on parenting style presents an oversimplification of the parenting style data. However, given the nature of the variables in the analysis, we judged that using a categorical parenting variable in a mixed-measures ANCOVA was the most straightforward way of presenting all of the data in a single analysis. We did, however, use a series of preliminary multiple regression analyses to assess links between the three continuous parenting style variables and the outcomes of interest (the six scales measuring likelihood of prompting an apology across the various transgression and victim type combinations). Across the six outcome measures, the results were very consistent with the results reported in the present paper: permissive parenting style was negatively associated with apology prompting, whereas authoritative and authoritarian parenting were positively associated with apology promoting.

Commonly-used guidelines (e.g., Cohen, 1988) view eta-squared and partial eta-squared sizes of .01 as small, and sizes of .06 as medium. Thus, we sought to remove effect sizes that were firmly in the small range in order to present a more parsimonious picture of the findings.

Lunney (1970) and others (e.g., D’Agostino, 1971) demonstrated that ANOVAs can be used with dichotomous data when certain criteria are met. These criteria are: “(a) the proportion of responses in the smaller response category is equal to or greater than .2 and there are at least 20 degrees of freedom for error, or (b) the proportion of responses in the smaller response category is less than .2 and there are at least 40 degrees of freedom for error” (Lunney, 1970, p. 263). In the present study, these criteria were met for all ANOVAs that were used to analyze dichotomous data. We also note that this approach has been used in several recent studies (e.g., Habermas, Meier, & Mukhtar, 2009; Laupa & Tse, 2005; Malti, Gasser, & Buchmann, 2009).

The similarity of the parent groups (for only those parents who indicated that learning to apologize was important in all three scenarios) was established by comparing their responses on all of the justification questions related to the importance of apology. There were 27 items, resulting in 27 comparisons, meaning that the analysis-wide significance level was set to .002. The omnibus p-values from the ANOVAs ranged from a low of .05 to a high of .95 (and there was only one p-value at .05).

References

- Abuhatoum S, Howe N. Power in sibling conflict during early and middle childhood. Social Development. 2013;22(4):738–754. [Google Scholar]

- Alink LRA, Mesman J, van Zeijl J, Stolk MN, Juffer F, Koot HM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. The Early Childhood Aggression Curve: Development of Physical Aggression in 10- to 50-Month-Old Children. Child Development. 2006;77(4):954–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Linden W, Habra ME. Influence of Apologies and Trait Hostility on Recovery from Anger. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29(4):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4(1, Pt.2):1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The development of instrumental competence through socialization. In: Pick AD, editor. Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology. Vol. 7. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1973. pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. The discipline controversy revisited. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 1996;45(4):405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant BK. Conflict resolution strategies in relation to children’s peer relations. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 1992;13(1):35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Buri JR. Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;57(1):110–119. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TY, Asher SR. Children’s goals and strategies in peer conflict situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Critchley CR, Sanson AV. Is parent disciplinary behavior enduring or situational? A multilevel modeling investigation of individual and contextual influences on power assertive and inductive reasoning behaviors. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27(4):370–388. [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24(4):349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F. Crime and punishment: Distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analyses in moral judgment. Cognition. 2008;108(2):353–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F, Dreber A, Wang Y, Costa J. Accidental outcomes guide punishment in a “trembling hand” game. Plos ONE. 2009;4(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino RB. A second look at analysis of variance on dichotomous data. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1971;8(4):327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Campos JJ. Domain differences in early social interactions. Child Development. 2013;84(3):817–825. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby BW, Schlenker BR. Children’s reactions to apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1982;43(4):742–753. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JD, Lynam D. Aggression and Antisocial Behavior in Youth. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 719–788. [Google Scholar]

- Ely R, Gleason JB. I’m sorry I said that: Apologies in young children’s discourse. Journal of Child Language. 2006;33(3):599–620. doi: 10.1017/s0305000906007446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DP. Conflict management in cross-cultural perspective. In: Aureli F, de Waal FBM, editors. Natural conflict resolution. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. pp. 334–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Graziano WG. How children become friends. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1983;48(3, Serial No. 201):1–86. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Kuczynski L. Direction of effect in socialization: A comparison of the parent’s versus the child’s behavior as determinants of disciplinary techniques. Developmental Psychology. 1980;16(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas T, Meier M, Mukhtar B. Are specific emotions narrated differently? Emotion. 2009;9(6):751–762. doi: 10.1037/a0018002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW. Conflict and friendship relations. In: Shantz CU, Hartup WW, editors. Conflict in child and adolescent development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 186–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Grusec JE. Parenting goals as organizers of responses to parent-child disagreement. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(3):465–479. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson L. The Social Contexts of Apology in Dispute Settlement: A Cross-Cultural Study. Ethnology. 1986;25(4):283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Miller PC. Enduring and different: A meta-analysis of the similarity in parents’ child rearing. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(2):223–254. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XL, Cillessen AN. Stability of continuous measures of sociometric status: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review. 2005;25(1):1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Mulvey KL, Richardson C, Jampol N, Woodward A. The accidental transgressor: Morally-relevant theory of mind. Cognition. 2011;119(2):197–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Rizzo MT. Morality, intentionality and intergroup attitudes. Behaviour. 2014;151(2-3):337–359. doi: 10.1163/1568539X-00003132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laupa M, Tse P. Authority concepts among children and adolescents in the island of Macao. Social Development. 2005;14(4):652–663. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Finkelstein BD, Townsend Betts N. A developmental meta-analysis of peer conflict resolution. Developmental Review. 2001;21(4):423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Hartup WW, Koplas AL. Towards understanding peer conflict. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1996;42(1):76–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lazare A. On apology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez NL, Schneider HG, Dula CS. Parent Discipline Scale: Discipline choice as a function of transgression type. North American Journal of Psychology. 2002;4(3):381–393. [Google Scholar]

- Lunney GH. Using analysis of variance with a dichotomous dependent variable: An empirical study. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1970;7(4):263–269. [Google Scholar]

- Malti T, Gasser L, Buchmann M. Aggressive and prosocial children’s emotion attributions and moral reasoning. Aggressive Behavior. 2009;35(1):90–102. doi: 10.1002/ab.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Rachal KC, Sandage SJ, Worthington EJ, Brown SW, Hight TL. Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(6):1586–1603. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.6.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of boys’ physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Development. 1999;70(5):1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nucci L. Education in the moral domain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ohbuchi K, Kameda M, Agarie N. Apology as aggression control: Its role in mediating appraisal of and response to harm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56(2):219–227. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald ME, Orth U, Aeberhard M, Schneider E. Punitive Reactions to Completed Crimes versus Accidentally Uncompleted Crimes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2005;35(4):718–731. [Google Scholar]

- Pirie F. Legal Autonomy as Political Engagement: The Ladakhi Village in the Wider World. Law & Society Review. 2006;40(1):77–104. [Google Scholar]

- Putallaz M, Sheppard BH. Social status and children’s orientations to limited resources. Child Development. 1990;61(6):2022–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk M. Values held by mothers for handicapped and non-handicapped preschoolers. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1984;30:403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Ross HS, Conant CL. The social structure of early conflict: Interaction, relationships, and alliances. In: Shantz CU, Hartup WW, editors. Conflict in child and adolescent development. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 153–185. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Ramini G, Pomerantz EM. Parental involvement and children’s motivation and achievement: A domain-specific perspective. In: Wentzel K, Miele D, editors. Handbook of motivation at school. 2nd. Routledge, Taylor, & Francis; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Wakebe T. How do young children judge intentions of an agent affecting a patient? Outcome-based judgment and positivity bias. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2014;118:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleien S, Ross H, Ross M. Young children’s apologies to their siblings. Social Development. 2010;19(1):170–186. [Google Scholar]

- Shook EV. Ho’oponopono. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Preschool children’s conceptions of moral and social rules. Child Development. 1981;52(4):1333–1336. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Morality in context: Abstractions, ambiguities, and applications. In: Vasta R, editor. Annals of Child Development. Vol. 10. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1995a. pp. 83–130. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Parenting styles and conceptions of parental authority during adolescence. Child Development. 1995b;66(2):299–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Parenting and the development of social knowledge reconceptualized: A social domain analysis. In: Grusec JE, Kuczynski L, editors. Parenting and children’s internalization of values: A handbook of contemporary theory. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 162–192. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Kochanska G, Chuang S. Mothers’ conceptions of everyday rules for young toddlers: A longitudinal investigation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46(3):391–416. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Jambon M, Ball C. The social domain approach to children’s moral and social judgments. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. 2nd. New York, NY, US: Psychology Press; 2014. pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Chen D, Harris PL. When the happy victimizer says sorry: Children’s understanding of apology and emotion. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2010;28(4):727–746. doi: 10.1348/026151009x475343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Harris PL. He didn’t want me to feel sad: Children’s reactions to disappointment and apology. Social Development. 2012;21(2):215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton J, Smith PK, Swettenham J. Bullying and ‘theory of mind’: A critique of the ‘social skills deficit’ view of anti-social behaviour. Social Development. 1999;8(1):117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of morality. In: Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3, Social, emotional, and personality development. 6th. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2006. pp. 789–857. [Google Scholar]

- Vaish A, Carpenter M, Tomasello M. Young children’s responses to guilt displays. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(5):1248–1262. doi: 10.1037/a0024462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Bernas R, Eberhard P. Responding to children’s everyday transgressions in Chinese working-class families. Journal of Moral Education. 2008;37(1):55–79. [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Cushman F, Hauser M, Saxe R. The neural basis of the interaction between theory of mind and moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(20):8235–8240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, Wagner E, Chapman M. Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28(1):126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Helwig CC, Lau A. Intention, act, and outcome in behavioral prediction and moral judgment. Child Development. 1996;67(5):2478–2492. [Google Scholar]