Abstract

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a highly conserved glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored membrane protein that is involved in the signal transduction during the initial phase of neurite outgrowth. The Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA) is a small GTPase that is known to have an essential role in regulating the development, differentiation, survival, and death of neurons in the central nervous system. Although recent studies have shown the dysregulation of RhoA in a variety of neurodegenerative diseases, the role of RhoA in prion pathogenesis remains unclear. Here, we investigated the regulation of RhoA-mediated signaling by PrPC using both in vitro and in vivo models and found that overexpression of PrPC significantly induced RhoA inactivation and RhoA phosphorylation in hippocampal neuronal cells and in the brains of transgenic mice. Using siRNA-mediated depletion of endogenous PrPC and overexpression of disease-associated mutants of PrPC, we confirmed that PrPC induced RhoA inactivation, which accompanied RhoA phosphorylation but reduced the phosphorylation levels of LIM kinase (LIMK), leading to cofilin activation. In addition, PrPC colocalized with RhoA, and the overexpression of PrPC significantly increased neurite outgrowth in nerve growth factor-treated PC12 cells through RhoA inactivation. However, the disease-associated mutants of PrPC decreased neurite outgrowth compared with wild-type PrPC. Moreover, inhibition of Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) substantially facilitated neurite outgrowth in NGF-treated PC12 cells, similar to the effect induced by PrPC. Interestingly, we found that the induction of RhoA inactivation occurred through the interaction of PrPC with RhoA and that PrPC enhanced the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP (a GTPase-activating protein). These findings suggest that the interactions of PrPC with RhoA and p190RhoGAP contribute to neurite outgrowth by controlling RhoA inactivation and RhoA-mediated signaling and that disease-associated mutations of PrPC impair RhoA inactivation, which in turn leads to prion-related neurodegeneration.

The activity of Rho GTPases (Rho, Rac, and Cdc42) is controlled by regulatory proteins that cycle between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. Rho GTPases are activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), which catalyze the exchange of GDP for GTP. In contrast, GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which stimulate Rho GTPase activity, and Rho guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs), which inhibit the exchange of GDP for GTP in the cytoplasm by forming a Rho–RhoGDI complex, induce inactivation state of these GTPases.1, 2 Furthermore, the Rho–RhoGDI complex needs to be dissociated by GDI displacement factor (GDF) before Rho GTPases are activated by GEFs.3 Activated Rho GTPases stimulate effector proteins, such as Rho-associated kinase (ROCK), mDia, and p21-activated kinase (PAK). Rho GTPases have roles in a variety of cellular functions including cytoskeletal rearrangement.4 In particular, the Ras homolog gene family member A (RhoA) and RhoA regulatory proteins (including p190RhoGAP and RhoGDI) participate in neuronal differentiation processes, such as neurite outgrowth, neuronal migration, axonal growth, and dendritic spine formation and maintenance.5 In addition, several studies have shown that RhoA inactivation is essential for neuronal morphogenesis.6, 7 Application of C3 toxin (a RhoA inhibitor) or Y27632 (a ROCK inhibitor) and overexpression of dominant-negative mutant RhoA enhanced neurite outgrowth from PC12 cells in response to nerve growth factor (NGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and cAMP.8, 9

The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a cell-surface glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoprotein attached to the plasma membrane.10 PrPC has been associated with various cellular functions, including the cell cycle, cell growth, cell proliferation, cell–cell adhesion, cell migration, and the maintenance of cell shape.11, 12 PrPC is strongly expressed in the central nervous system (CNS) and can act as a regulator of neuronal development, differentiation, and neurite outgrowth, which may depend on interactions with various regulatory proteins, including heparan sulfate proteoglycans,13, 14 stress-inducible protein-1,15 Grb2 protein,16 caveolin,17 neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs),18, 19 and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins.20, 21 In addition, PrPC exerts its functions by interacting with several kinases, including Fyn, protein kinase C (PKC), protein kinase A (PKA), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt, and extracellular regulated kinases (ERK1/2).22, 23

Loss of PrPC function has been implicated in neuronal polarization and neurite outgrowth through the modulation of integrin–ECM interactions and the RhoA-ROCK-LIM kinase (LIMK)-cofilin signaling pathway.24 Recently, ROCK overactivation and ROCK-3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) complex formation were shown to contribute to the regulation of neuronal polarity and the generation of pathogenic prions.25 However, the functional interaction between PrP and RhoA-related signaling molecules remains unknown.

In this study, we investigated the relationships of PrPC expression with RhoA activity and neurite outgrowth. We demonstrated that PrPC induced neurite outgrowth by inactivating RhoA and that PrPC-mediated RhoA inactivation may be achieved by the interaction of PrP with RhoA and/or p190RhoGAP, resulting in the phosphorylation of RhoA at Ser188.

Results

PrPC regulates RhoA activation and RhoA-mediated signaling

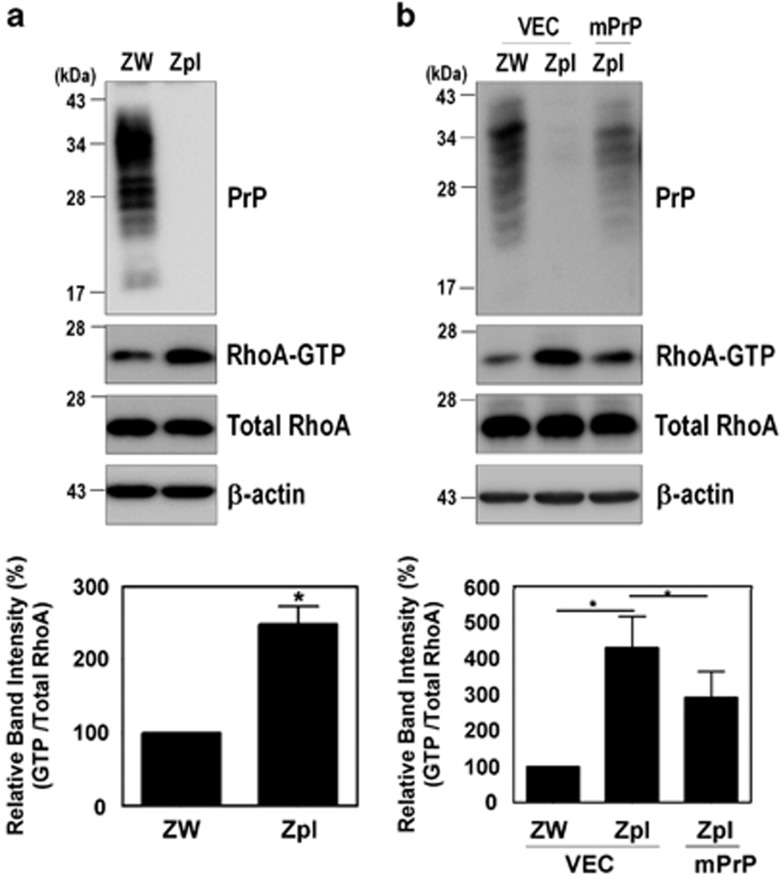

To determine whether the PrPC affects RhoA activity, a pull-down assay was performed with the glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-Rhotekin-Rho-binding domain (RBD) in the ZW13-2 (wild-type, WT) and Zpl3-4 (PrP knockout) mouse hippocampal neuronal cell lines (Supplementary Figure 1), as previously established.26 We found that the level of RhoA-GTP in PrP knockout Zpl cells was significantly higher than in control ZW cells (Figure 1a). We confirmed this result by re-introducing mouse PrP (mPrP) into Zpl cells, which exhibited lower RhoA-GTP levels than Zpl cells that expressed the empty vector alone (Figure 1b). These results suggest that PrPC negatively regulates RhoA activity in hippocampal neuronal cells.

Figure 1.

PrPC regulates RhoA activation. (a and b) Detection of RhoA-GTP by GST-Rhotekin-RBD pull-down assay in cells expressing PrPC (ZW) and PrP knockout (Zpl) with or without expressing mPrP. The level of RhoA-GTP was determined by western blot with anti-RhoA antibody following a pull-down assay. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, n=3)

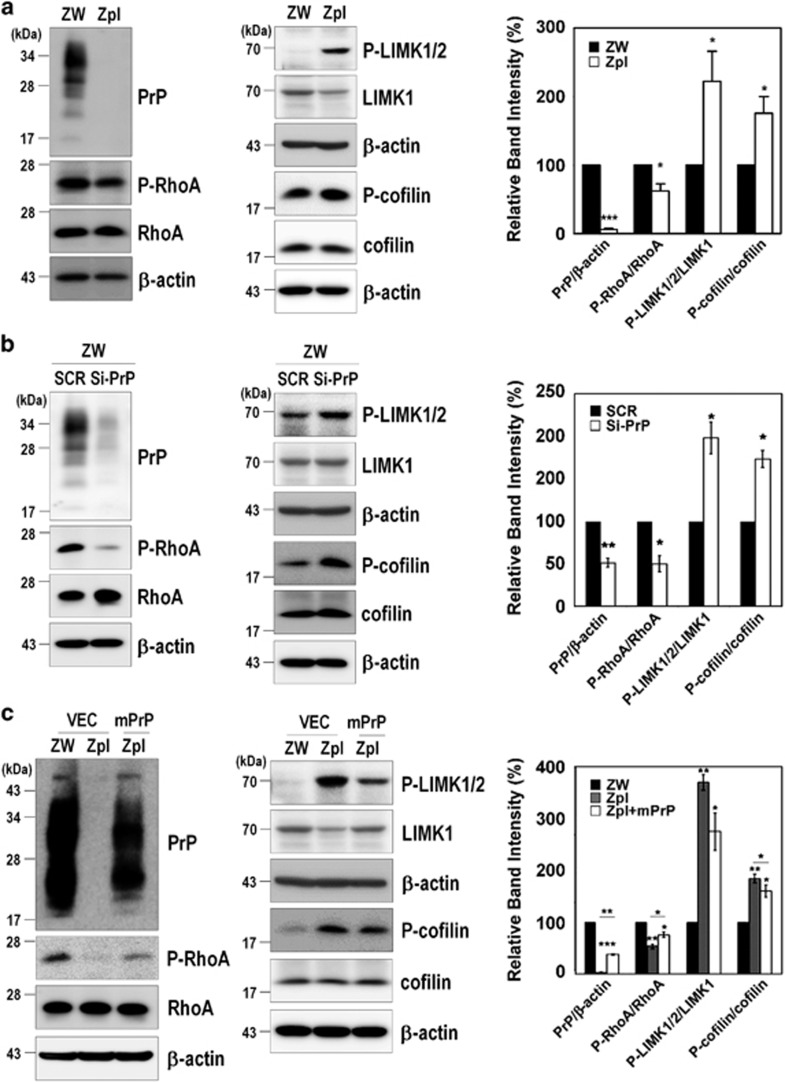

To further investigate the signaling pathway of RhoA regulated by PrPC expression, we determined whether PrPC modulates the RhoA-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway. As shown in Figure 2, PrP knockout and siRNA-mediated knockdown of endogenous mPrP (si-mPrPC) cells exhibited less phosphorylated RhoA at Ser188 (p-RhoA), which negatively regulates RhoA activity by enhancing its interaction with RhoGDI and translocates RhoA from the membrane to the cytosol27 with increases in phospho-LIMK1/2 (p-LIMK1/2) and phospho-cofilin (p-cofilin) (Figures 2a and b). Supporting these results, the re-introduction of mPrP reversed the changes in the levels of p-RhoA, p-LIMK1/2, and p-cofilin compared with Zpl cells expressing the empty vector alone, yielding a result similar to that observed for the ZW cells (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

PrPC modulates the RhoA-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway. (a-c) Phosphorylation of RhoA, LIMK1/2, and cofilin in ZW and Zpl cells (a), in ZW cells transfected with scrambled RNA (SCR) or mPrP-targeted siRNA (Si-PrP) (b) and in Zpl cells with or without expressing mPrP (c) was analyzed in triplicate by western blot. The intensities of the bands in each panel were measured and quantified for each group, and the values are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=3)

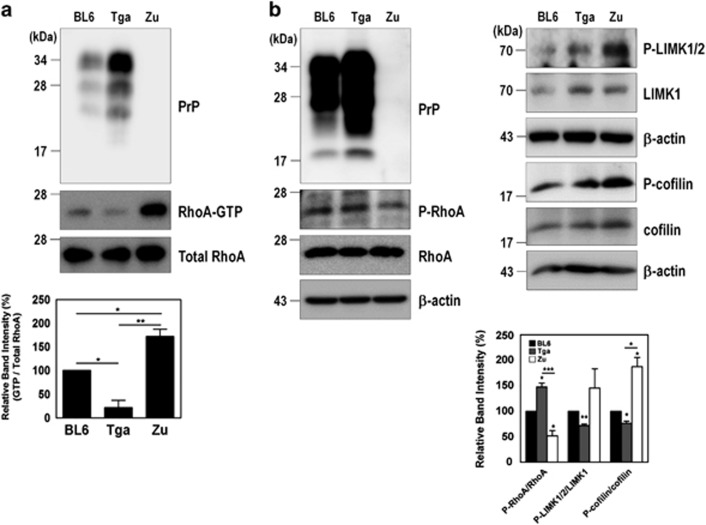

To confirm these results, we examined the effect of PrPC expression on RhoA activity and on the phosphorylation levels of RhoA downstream proteins in the brains of three different types of mice: WT (C57BL/6J) mice, Tga20 mice that overexpress PrPC (Tga20), and Zürich I Prnp-deficient (Zürich I) mice that lack PrPC. As expected, we observed an increase in RhoA-GTP level (Figure 3a) accompanied by a decrease in p-RhoA and increases in both p-LIMK1/2 and p-cofilin (Figure 3b) in the brains of the Zürich I mice compared with the brains of the WT and Tga20 mice. These findings suggest that the expression of PrPC inactivates RhoA activity and subsequently affects its downstream regulatory proteins including LIMK and cofilin.

Figure 3.

PrPC is involved in RhoA inactivation in the brains of three different types of mice. (a) Detection of RhoA-GTP levels in the brains of C57BL/6J (BL6, WT), Tga20 (Tga, PrP overexpression) and Zürich I (Zu, PrP-deficient) mice (n=3 per each group). (b) Phosphorylation of RhoA, LIMK, and cofilin was assessed in the whole-brain lysates of C57BL/6J, Tga20, and Zürich I mice. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=3)

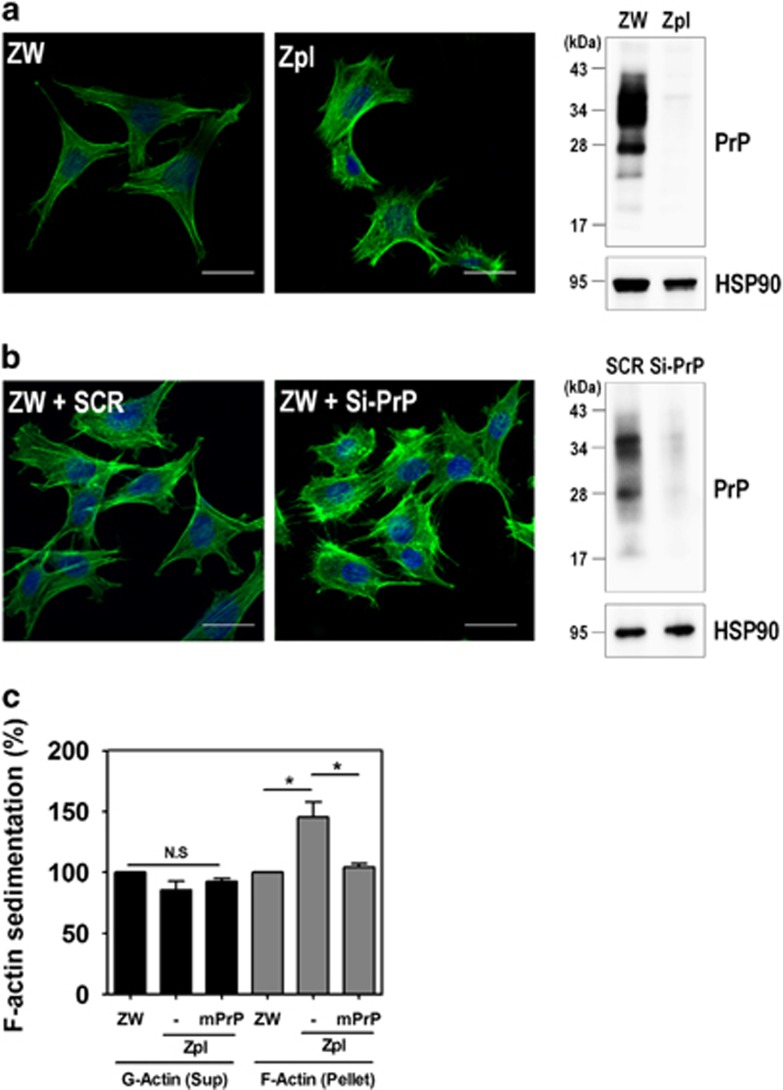

PrPC controls F-actin formation through the RhoA/ROCK pathway

Previous studies have reported that RhoA activation has a role in the regulation of cytoskeleton reorganization through the formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions.28, 29 Thus, we investigated the effect of PrPC on the formation of actin stress fibers in ZW and Zpl cells. Stress fibers were observed to form filamentous actin (F-actin), which was detected with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated phalloidin. As shown in Figure 4a, F-actin formation was more strongly detected in Zpl cells than in ZW cells, and silencing PrPC in ZW cells markedly enhanced F-actin formation (Figure 4b). To confirm this finding, we determined the changes in G-actin and F-actin levels in ZW, Zpl, and Zpl cells expressing mPrP using G-actin/F-actin sedimentation assay. Consistent with the results of F-actin formation, PrP knockout (Zpl cells) resulted in significantly increased F-actin sedimentation in the pellet fraction, whereas G-actin levels were not changed in the supernatant fraction (Figure 4c). To further elucidate whether F-actin formation regulated by PrPC is due to RhoA-mediated signaling, cells were treated with Y27632, an inhibitor of ROCK. Interestingly, Y27632 treatment decreased F-actin formation in ZW cells (Supplementary Figure 2a). In addition, we analyzed PrPC on F-actin-mediated cell adhesion using WST-1 reagent, which is a quantitative method for evaluating attached cells. In a cell adhesion assay, F-actin-mediated cell adhesion was significantly decreased in Zpl cells than ZW or Zpl cells expressing mPrP (Supplementary Figure 3). These findings indicate that PrPC is involved in F-actin formation and cell adhesion through the RhoA/ROCK signaling pathway.

Figure 4.

Depletion of PrPC increases F-actin formation. (a and b) Immunocytochemical staining for F-actin in ZW and Zpl cells (a), and ZW cells transfected with either scrambled RNA (SCR) or mPrP-targeted siRNA (Si-PrP) (b) using Alexa Fluor 488-phalloidin (green). DAPI (blue) was used to counterstain the nuclei. All pictures are representative of multiple images from three independent experiments (scale bars, 20 μm). The expression of PrPC was determined by western blot with anti-PrP (3F10) antibody and HSP90 was used as a loading control. (c) The expression of F-actin assessed by a sedimentation assay in ZW, Zpl, and Zpl expressing mPrP cells was analyzed by western blot with anti-β-actin, anti-PrP (3F10) and anti-HSP90 antibodies. The intensities of the bands in each panel were measured and quantified for each group, and the values are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, n=3)

PrPC interacts with both RhoA and p190RhoGAP

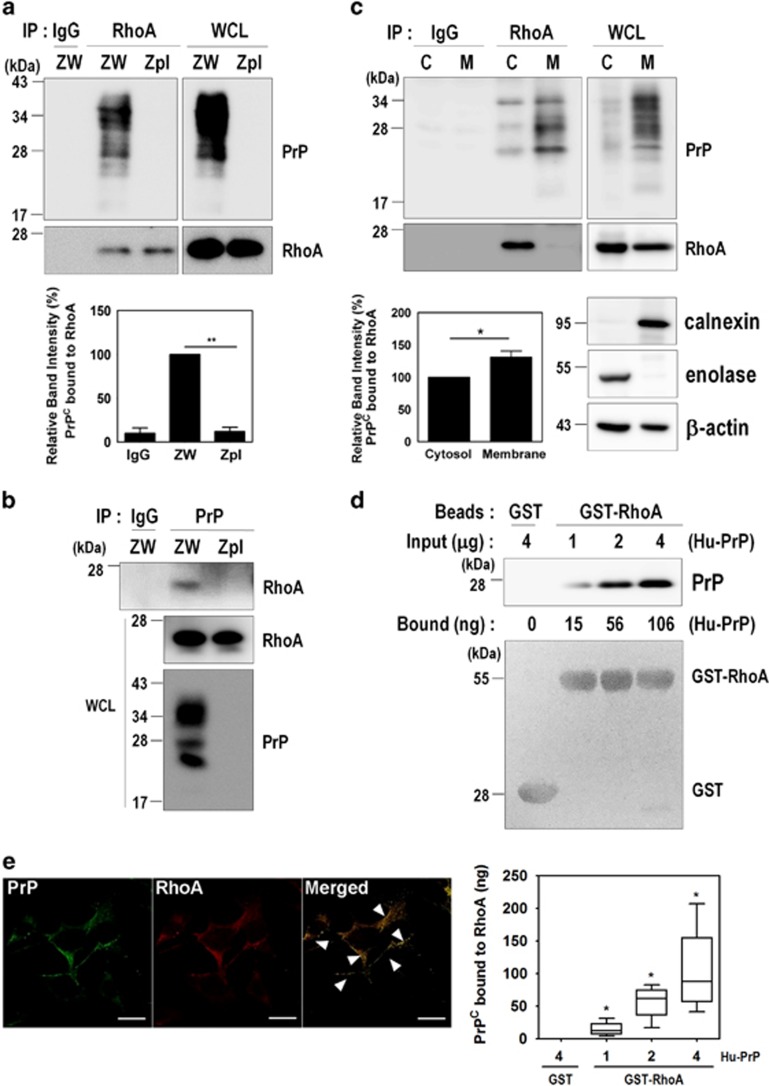

To identify the molecular mechanism by which PrPC induces RhoA inactivation, we sought to determine whether PrPC and RhoA directly interact in ZW and Zpl cells. As PrPC possesses a partial sequence homology with RhoA and RhoA effector proteins, including rhotekin, ROCK1, protein kinase N (PKN), and rhophilin (Supplementary Figure 5), we confirmed the interaction of PrPC with RhoA using a co-immunoprecipitation assay in ZW cells (Figures 5a and b). To further verify whether the interaction between PrPC and RhoA occurs in the cytosol or membrane fractions in ZW cells, co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA and PrPC was conducted on both fractions. As shown in Figure 5c, the interaction between PrPC and RhoA in the membrane fraction was slightly increased compared with the cytosol fraction, although the level of RhoA in the cytosol fraction was higher than the level in the membrane fraction (Figure 5b). Furthermore, purified human recombinant PrPC protein directly bound to purified recombinant GST-RhoA protein in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5d). We also found that PrPC was colocalized with RhoA in the cytoplasm and the plasma membrane of ZW cells (Figure 5e, arrowheads), suggesting that PrPC directly interacts with RhoA in both the cytoplasm and the membrane.

Figure 5.

PrPC interacts with RhoA. (a and b) Co-immunoprecipitation of PrP with RhoA using ZW and Zpl cell lysates were performed with either anti-RhoA (a) or anti-PrP (3F10) (b) antibodies, and then analyzed by western blot with anti-PrP and anti-RhoA antibodies, respectively. WCL, whole-cell lysates. (c) The subcellular fractions from ZW cells were used to immunoprecipitate RhoA with anti-RhoA antibody and then analyzed by western blot with anti-PrP (3F10) and anti-RhoA antibodies. Enolase and calnexin were used as makers for the cytosol (C) and membrane (M) fractions, respectively. β-Actin as a loading control. (d) GST and GST-RhoA beads were incubated with human recombinant PrP (Hu-PrP) as indicated, and the level of Hu-PrP bound to GST-RhoA was determined by western blot with anti-PrP (3F4) antibody. The boxplot showing the means±S.E. of abundance of the PrP-RhoA complex, was calculated from the BSA standard curve in three (n=3) independent experiments. The GST and GST-RhoA samples were stained with Ponceau S to confirm the equal loading. (e) Colocalization of PrP with RhoA was assessed by double immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. All above data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=3)

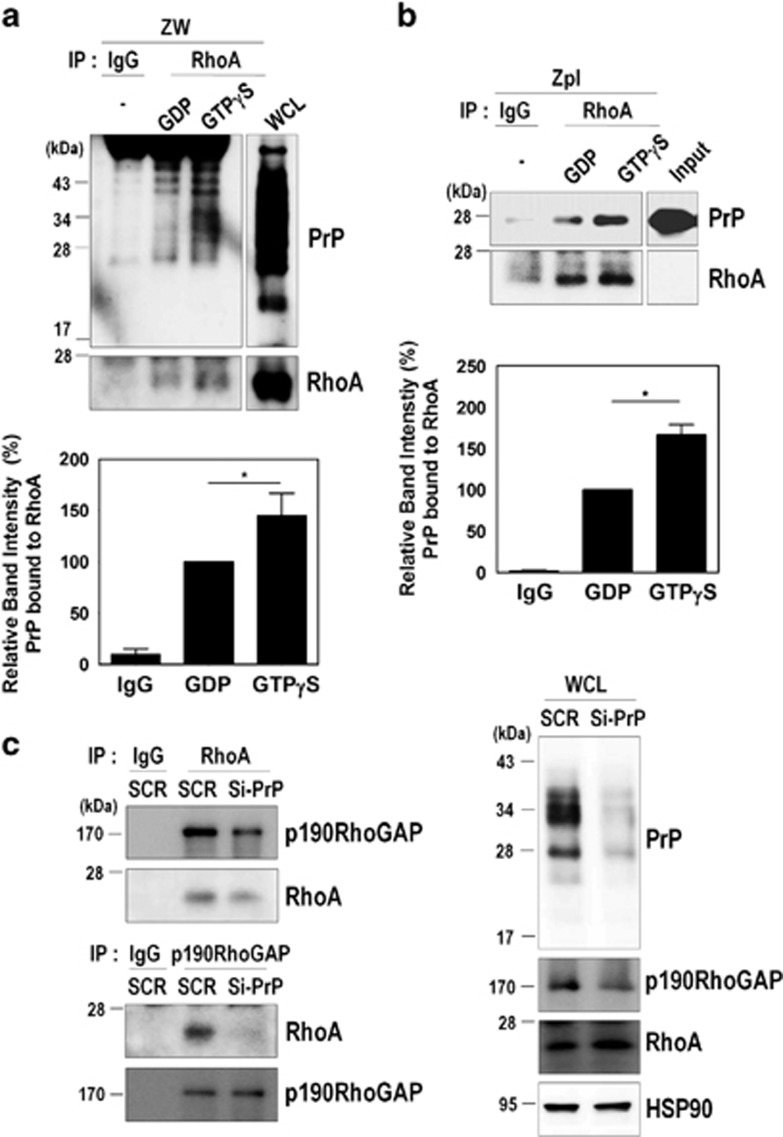

As RhoA functions as a molecular switch between active GTP-bound and inactive GDP-bound states, we next investigated whether the GDP- or GTP-bound states of RhoA affect its interaction with PrPC. ZW cell lysates were preloaded with either GDP or GTPγS, and then co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA with PrP was performed. We found that PrPC preferentially interacts with active GTPγS-bound RhoA compared with GDP-bound RhoA in ZW cells (Figure 6a). In addition, the interaction of purified human recombinant PrPC with RhoA was also increased in the presence of GTPγS in ZPL cells (Figure 6b). These results showed that PrPC induced RhoA inactivation through a direct interaction with RhoA in the cytosol and membrane fractions of PrPC-expressing cells and that GTP-bound RhoA may more favorably interact with PrPC.

Figure 6.

PrPC binds to GTP-bound RhoA and p190RhoGAP. (a) ZW cell lysates were preloaded with GDP or GTPγS followed by immunoprecipitation with the anti-RhoA antibody and analyzed by western blot using the anti-PrP (3F10) and anti-RhoA antibodies. WCL, whole-cell lysates. (b) Zpl cell lysates preloaded with GDP or GTPγS were immunoprecipitated with anti-RhoA antibody, incubated with 2 μg of human recombinant PrP (Hu-PrP), and analyzed by western blot with the anti-PrP (3F4) and anti-RhoA antibodies. (c) The co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA or p190RhoGAP using ZW cells transiently transfected with either SCR or Si-PrP was detected by western blot using anti-p190RhoGAP and anti-RhoA antibodies, respectively. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, n=3)

The p190RhoGAP is known to be a major regulator of RhoA activity,30, 31 it contributes to actin rearrangement and neurite outgrowth through binding to GTP-bound RhoA and subsequently enhancing the hydrolysis of GTP.32 Thus, we examined whether PrPC regulates RhoA inactivation by facilitating the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP. As expected, reducing PrPC expression by si-PrPC decreased its interactions with both RhoA and p190RhoGAP (Figure 6c). These findings indicate that PrPC interacts with RhoA, as well as p190RhoGAP, and that PrPC mediates the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP.

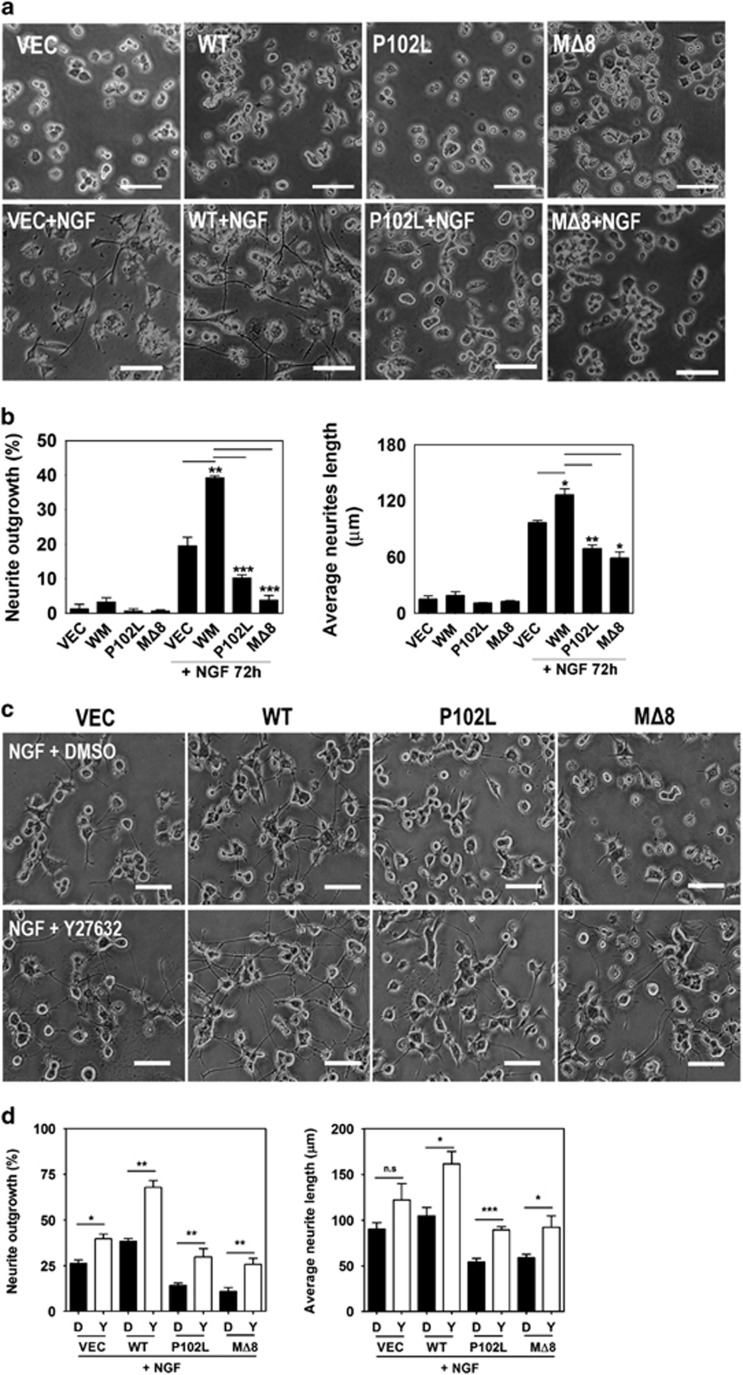

The disease-associated PrPC mutants impair neurite outgrowth

Point mutations and polymorphisms of PrPC are associated with genetic prion diseases,33 and several studies have shown an association between the pathogenicity of prion diseases and neuronal differentiation.34, 35 Therefore, we investigated whether the disease-associated mutations of PrPC affect NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells stably expressing WT or disease-associated mutants of PrPC (P102L and MΔ8). Interestingly, the PC12 cells expressing WT PrPC exhibited enhanced neurite outgrowth and neurite length in response to NGF, whereas the cells expressing disease-associated PrPC mutants impaired neurite outgrowth and reduced neurite length (Figures 7a and b). In addition, the inhibition of ROCK by Y27632 treatment significantly enhanced neurite outgrowth and neurite length (Figures 7c and d). Using mutants of RhoA (S188D, mimicking the phosphorylated form; S188A, mimicking the dephosphorylated form), we found that RhoA phosphorylation (Ser188) induced neurite outgrowth in NGF-differentiated PC12 cells expressing PrPC (Supplementary Figure 4). These data indicate that PrPC may facilitate neurite outgrowth and affect the cellular signal transduction related to RhoA inactivation and that the phosphorylation of RhoA at Ser188 can also enhance PrPC-mediated neurite outgrowth.

Figure 7.

The disease-associated mutations of PrPC impair neurite outgrowth. (a and b) PC12 cells stably expressing either vector, WT, P102L, or MΔ8 were treated with 50 ng/ml NGF for 72 h. (c and d) The cells expressing either vector, WT, P102L, or MΔ8 were incubated with or without 10 μM Y27632 in the presence of NGF. Changes in the cell morphology, neurite length, and neurite numbers were determined under a microscope. The data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, n=3)

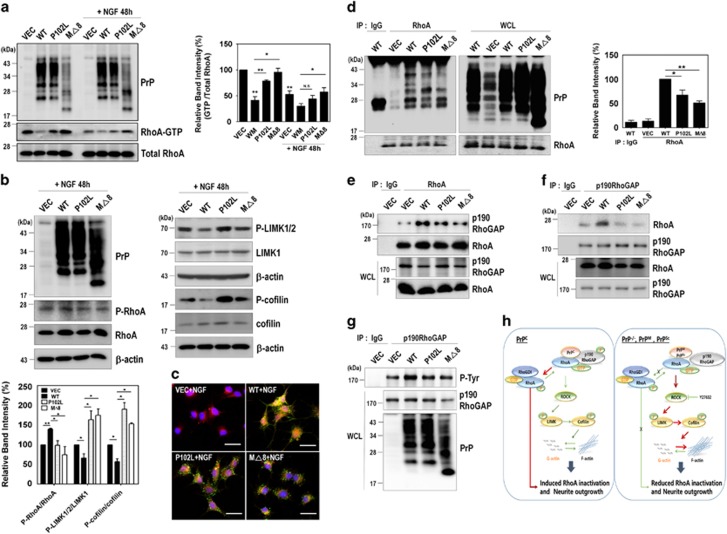

The disease-associated mutations of PrPC affect RhoA signaling through reduced interaction with RhoA and p190RhoGAP

To investigate the effect of disease-associated mutations of PrPC on RhoA activity, PC12 cells were transiently transfected with an empty vector, WT PrPC, or disease-associated mutants of PrPC, and then treated with NGF. Interestingly, we observed that RhoA-GTP levels were increased in PC12 cells expressing disease-associated mutants of PrPC compared with the cells expressing WT PrPC, although these changes were lower in the presence of NGF (Figure 8a). Interestingly, decrease in p-RhoA and increases in both p-LIMK1/2 and p-cofilin were detected in the cells expressing disease-associated mutants of PrPC compared with the cells expressing WT PrPC (Figure 8b). These results, which are correlated with those in PrP knockout or knockdown cells, indicate that PrPC regulates neurite outgrowth through inactivation of RhoA and the Rho/ROCK signaling pathway. Next, we examined whether these disease-associated mutations of PrPC affect the interactions between not only PrPC and RhoA but also RhoA and p190RhoGAP. We found that the colocalization of PrP with RhoA was significantly decreased in the cells expressing disease-associated mutants of PrPC compared with cells expressing PrPC WT based on immunofluorescence staining (Figure 8c). Consistently, the co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA with the disease-associated mutants of PrPC was significantly decreased (Figure 8d). Moreover, the overexpression of disease-associated PrPC mutants markedly decreased its interaction with RhoA and p190RhoGAP (Figures 8e and f). Notably, the disease-associated mutations of PrPC reduced p190RhoGAP tyrosine phosphorylation, which led to a decrease in p190RhoGAP activity (Figure 8g). Taken together, these findings suggest that the disease-associated mutations of PrPC impaired RhoA signaling and the interaction with RhoA and p190RhoGAP.

Figure 8.

The disease-associated mutants of PrPC affect RhoA signaling through the reduced interactions with RhoA and p190RhoGAP. (a and b) The level of RhoA-GTP following a pull-down assay (a) and the phosphorylation of RhoA, LIMK, and cofilin (b) was analyzed by western blot in PC12 cells expressing either vector, WT, P102L, or MΔ8 in response to NGF. (c) Colocalization of PrP with RhoA in the NGF-treated PC12 cells expressing either vector, WT, P102L, or MΔ8 was determined using confocal microscopy (green, PrP; red, RhoA; blue, DAPI). (d) HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with either vector, WT, P102L, or MΔ8. The co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA was detected by western blot using anti-PrP (3F4) and anti-RhoA antibodies. (e-g) PC12 cells transiently transfected WT or disease-associated mutants of PrPC were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-RhoA (e) and p190RhoGAP antibodies (f). (g) The p190RhoGAP phosphorylation (p-Tyr) was detected using p-Tyr antibody after p190RhoGAP immunoprecipitation. All above data are expressed as the mean±S.E. of three independent experiments (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, n=3). (h) PrPC–RhoA interaction stimulates RhoA inactivation and neurite outgrowth. In PrPC-expressing cells and mice, PrPC increased the phosphorylation of RhoA and p190RhoGAP, enhancing the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP. This complex led to the inactivation of RhoA and its downstream effectors. Subsequently, RhoA inactivation decreased actin polymerization and enhanced neurite outgrowth. In contrast, depleting PrPC or expressing disease-associated mutants of PrPC prevented RhoA inactivation and neurite outgrowth by interfering with the interaction

Discussion

The physiological activity of PrPC in many important aspects of cell biology, including neuritogenesis and cell signaling, has been well established.24, 25, 36 Recent studies have demonstrated that PrPC contributes to neuritogenesis through modulating the β1 integrin-coupled RhoA-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin signaling axis24 and that prion-induced ROCK overactivation is involved in neuronal polarity and prion pathogenesis.25 However, it is still unclear whether PrPC can directly regulate RhoA activity, and its related effector proteins have not yet been elucidated.

In this study, we discovered a novel mechanism by which PrPC controls RhoA activity and the RhoA-mediated signaling pathway (Figure 8h). Both knockdown and silencing of PrPC induce activation of RhoA, which is best known for its function in reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton into stress fibers and focal adhesions,5 in concert with altered activities of downstream effector proteins (i.e., LIMK and cofilin). In addition, PrPC expression is also involved in the regulation of focal adhesion dynamics and actin polymerization.37, 38 We also found that the depletion of PrPC or the expression of disease-associated PrPC mutants impaired actin cytoskeleton dynamics and inhibited neurite outgrowth, possibly via increased phosphorylation of cofilin (an inactive form), leading to microfilaments that support stabilization. Unphosphorylated cofilin (an active form) is known to sever F-actin, resulting in depolymerization of F-actin.29

The altered balance of cofilin activity is critical for the regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics and has been associated with neurodegeneration.39, 40 NADPH oxidase (NOX) is activated through a PrPC-dependent pathway in response to proinflammatory cytokines,41 and the overexpression of PrPC alone also induced NOX-mediated ROS generation leading to the activation of cofilin and its oxidation (Cys39 and Cys147) followed by cofilin-actin rod formation.42 We found that overexpression of PrPC significantly reduced the amount of p-cofilin, leading to cofilin activation without changes in the total level of cofilin through the RhoA-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway, and led to increased neurite outgrowth in NGF-treated PC12 cells. In addition, this regulation depends on the membrane environment and the interactions among membrane components (i.e., NOX isoforms, β1 integrin, laminin, and fyn), resulting in PrPC-dependent neuronal differentiation or synaptic dysfunction.

PrPC has been implicated in neurite outgrowth as an interacting partner with NCAM and laminin.18, 19, 43 In addition, several interacting partners have been reported to directly bind to PrPC, which enhances brain development, neuronal differentiation, and neuronal cell death in various cell lines and animal models.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 Moreover, these interactions can regulate various signaling pathways, such as PI3K/AKT,22, 44 ERK1/2,22, 23 and RhoA/Rac1/Cdc42.12 Interestingly, the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 pathways regulate transcriptional profiles that promote neurite extension.45 Activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 in conjunction with inhibition of RhoA activity increases neurite extension via posttranslational mechanisms – both pathways functionally connect with ROCK.46 We also demonstrated increased neurite extension and neurite length as a result of ROCK inhibition by Y27632, suggesting that PrPC exerts its influence on neuronal differentiation by modulating RhoA-mediated signaling effectors (i.e., ROCK and p190RhoGAP).

Specifically, we demonstrated the biological consequences of PrPC-mediated RhoA inactivation that results from the interaction of PrPC with RhoA and p190RhoGAP, and overexpressing PrPC results in increased tyrosine phosphorylation of p190RhoGAP, which elevates p190RhoGAP activity. Indeed, p190RhoGAP was reported to be activated through tyrosine phosphorylation by Src.47 In contrast, these results were not observed for the disease-associated mutants of PrPC. These findings suggest that PrPC may have a role in both the phosphorylation of p190RhoGAP and RhoA-p190RhoGAP complex formation.

p190RhoGAP is activated by the binding of β1 integrins and then translocates into a detergent-insoluble fraction upon adhesion to fibronectin and colocalizes with F-actin in lamellipodial protrusions.30, 48, 49 Furthermore, integrin clustering triggers RhoA inactivation through c-Src-dependent activation of p190RhoGAP,47 and p190RhoGAP-mediated RhoA inactivation effectively induces neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells.50 In addition, PKA phosphorylates RhoA at Ser188, resulting in its release from membranes through increased interactions with RhoGDI.51, 52 Furthermore, the interactions between RhoA and RhoGDI were reported to negatively regulate the cycling of RhoA activity at the leading edge in migrating cells.53 We showed that overexpression of the RhoA S188D mutant but not the S188A mutant promoted neurite outgrowth in the NGF-treated PC12 cells expressing PrPC. These data indicate that PrPC induced RhoA inactivation also through RhoA phosphorylation at Ser188. Furthermore, we demonstrated that PrPC is colocalized with RhoA and that it enhanced the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP in response to NGF. However, the interacting domains of PrPC and RhoA remain to be elucidated. In general, active RhoA induced actin–myosin interactions, resulting in cell contraction, although inactive RhoA were reported to prevent actin–myosin interaction, which may induce cell expansion and neurite outgrowth.54

In prion diseases, genetic mutations of PrPC induce spongiform encephalopathy and spontaneous neurodegeneration, and the disease-associated mutations of PrPC lead to severe ataxia, apoptosis, and extensive central and peripheral myelin degeneration.55, 56 As shown in this study, overexpression of the disease-associated mutants of PrPC (P102L and MΔ8) impaired neurite outgrowth because of the failure to inactivate RhoA and reduced the co-immunoprecipitation of RhoA and p190RhoGAP. Interestingly, scrapie infection increases RhoA activation by decreasing the interaction between RhoA and p190RhoGAP (manuscript in preparation). Based on these findings, the disease-associated mutations of PrPC and scrapie infection partially suppress neuronal differentiation via the failure to inactivate RhoA.

Taken together, our results showed that PrPC contributes to RhoA inactivation, leading to neuritogenesis and that disease-associated mutants of PrPC failed to inactivate RhoA, which in turn leads to prion-related neurodegeneration. These findings are important for understanding the mechanisms of PrPC-mediated neuronal differentiation and survival.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Y27632, and the anti-β-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Anti-RhoA, anti-Rac1, anti-Cdc42, anti-RhoGDI, and anti-cofilin antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). NGF and the anti-p190RhoGAP antibody were purchased from Millipore (Lake Placid, NY, USA). Anti-p-RhoA (S188), anti-p-LIMK1/2, anti-LIMK1, and anti-LIMK2 antibodies were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). The anti-p-cofilin antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Cell culture, transfection, and generation of stable cell lines

Mouse hippocampal neuronal cell lines, including ZW13-2 (WT PrP) and Zpl3-4 (PrP knockout) cells, were previously established.26 ZW and Zpl cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone), 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Transient transfections were carried out using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's directions. For siRNA transfection, ZW cells were transfected with siRNA targeting human PrP (150 pmol/ml) for 72 h to silence PrP expression. PC12 cells stably expressing the pcDNA3.1/Zeo(+) vector or vector encoding human PrPs (WT; P102L, the most common GSS-causing mutation; MΔ8, octapeptide repeat deletions) were generated using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent, followed by selection and maintenance in the presence of 250 μg/ml Zeocin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PC12 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum (HS, Hyclone), 5% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C under 5% CO2.

Animals

The Prnp-transgenic (Tga20) and Prnp-deficient mice (Zürich I) were kindly provided by Dr. C Weissmann (Department of Infectology, Scripps Florida, Jupiter, FL, USA) and Dr. A Aguzzi (Institute of Neuropathology, University Hospital of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland), respectively. The WT control male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Young Bio (Seongnam, Republic of Korea). The Tga20, Zürich I and WT control C57BL/6J mice were housed in a clean facility under natural light-dark cycle conditions (12-h/12-h light/dark cycle) and examined at 8–10 weeks of age. All experiments were performed in accordance with Korean laws and with the approval of the Hallym Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (HMC2015-0-0411-3).

Induction of neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells

To assess neurite outgrowth, the PC12 cells were plated at a density of 5 × 103 cells per well on 35 mm culture dishes coated with poly-d-lysine solution (Sigma-Aldrich). After 12 h, the PC12 cells were incubated with 50 ng/ml NGF2.5S (Millipore) for the indicated times in DMEM medium containing with 1% heat-inactivated HS, 0.5% heat-inactivated FBS, and 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. The quantity of neurite bearing cells was determined by counting at least 100 single cells/3 arbitrary positions per dish. A cell was identified to as positive for neurite outgrowth if it had at least a twofold increased cell body diameter. Cells were visualized using a phase-contrast microscope (200x, Nikon TS100, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blot analysis

Cells were collected and washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed with modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 10 min, and the protein concentrations in the supernatants were analyzed using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with the appropriate antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized on digital images captured with an ImageQuant LAS4000 imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) using EzwestLumi plus western blot detection reagent (ATTO Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and the band intensities were quantified using ImageJ (NIH) program (Bethesda, MD, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism4 (San Diego, CA, USA).

Immunocytochemistry

PC12 cells were treated with 50 ng/ml NGF2.5S in DMEM media (supplemented with 1% heat-inactivated HS, 0.5% heat-inactivated FBS, and antibiotics) for the indicated times at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The cells were washed with PBS and fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 20 min at room temperature (RT). The cells were permeablized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and then the samples were blocked with 5% normal goat serum and 1% BSA in PBS for 15 min at RT. For fluorescence labeling, the cells were incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-RhoA (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat polyclonal anti-PrP (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The cells were washed and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated or rhodamine-conjugated anti-mouse or rabbit IgG (1:500) for 1 h, at RT. The immunolabeled cells were examined using a LSM 700 laser confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Immunoprecipitation

The cells were harvested and washed once with ice-cold PBS, and then lysed in modified RIPA buffer. The cell lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 13 000 × g and the supernatants were incubated with anti-RhoA, anti-p190RhoGAP, and anti-PrP (3F10)57 antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C. After antibody binding, protein A-conjugated Sepharose 4B beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added for 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were then washed three times with lysis buffer, and the bound proteins were eluted with 2 x Laemmli sample buffer by boiling. The samples were electrophoresed and analyzed by western blot with anti-RhoA, anti-p190RhoGAP, and anti-PrP (3F4 or 3F10)57, 58 antibodies.

GST-Rhotekin-RBD pull-down assay for activating RhoA

The cells were harvested and washed with PBS, and then lysed in binding/washing/lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 5% glycerol, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM EGTA) with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet. The lysates were centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was incubated with GST-Rhotekin-RBD to detect RhoA-GTP. The beads were washed three times with binding/washing/lysis buffer. The bound proteins were eluted with 2 x Laemmli sample buffer by boiling. The samples were electrophoresed and analyzed by western blot with the anti-RhoA antibody.

In vitro loading of GDP and GTPγS onto GTP-binding proteins

Cell lysates (500 μg/ml protein in 500 μl) were incubated with 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0). Next, 0.1 mM GTPγS or 1 mM GDP was added to the cell lysates, and the lysates were incubated at 30 °C for 15 min under constant agitation. The reaction was terminated by thoroughly mixing the sample with MgCl2 at a final concentration of 60 mM on ice.

In vitro GST-tagged protein–protein interactions

The purified recombinant GST and GST-RhoA proteins (10 μg/ml protein in 500 μl) were preincubated with glutathione (GSH)-sepharose 4B beads for 2 h at 4 °C in a binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1x PBS, and 10% glycerol,) with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet. To determine protein–protein interaction, GST and GST-RhoA beads were incubated with 1–4 μg of purified human recombinant PrP (Hu-PrP) for 2 h at 4 °C. After washing the beads, the bound proteins were eluted with 2 x Laemmli sample buffer by boiling. The samples were electrophoresed and analyzed by western blot with the anti-PrP antibody.

Subcellular fractionation

Confluent cells were harvested, washed with ice-cold PBS, and lysed by passing through a 23-gauge syringe needle for 10 cycles in cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 10 mM NaF, and 1 mM Na3VO4) with a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet. The lysates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min. The pellets that contained nuclei and nuclei-associated structures were solubilized with HEPES buffer (pH 7.2) containing 400 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and the protease inhibitor cocktail and were agitated on ice for 30 min. The postnuclear supernatants were centrifuged at 100 000 x g for 1 h at 4 °C to separate the membrane pellet and the cytosolic fraction. The membrane pellets were washed with ice-cold PBS and suspended in RIPA buffer by rocking for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 13 000 x g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant, containing the solubilized membrane proteins, was considered the membrane fraction.

F-actin sedimentation assay

Cells were harvested and washed with PBS, and then lysed in 0.1% Triton X-100 and F-actin stabilization PHEM buffer (60 mM PIPES, 25 mM HEPES, 10 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysates were carefully mixed and directly transferred into a TLA 100 centrifuge tube (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The lysates were centrifuged at 100 000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C in a table top ultracentrifuge (Beckman Instruments), which yielded a clear supernatant. At these high centrifugal forces, all F-actin in the system is expected to pellet, leaving G-actin in the supernatant. The F-actin pellet was washed twice in ice-cold PHEM buffer and suspended in SDS buffer. Protein concentration of the fractions was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit. Equal amounts of proteins were electrophoresed, and transferred to PVDF membrane for probing with anti-β-actin antibody. The densitometric quantification of the western blot determined the comparable levels of G- and F-actin using Image J software.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean±S.E. of at least three independent experiments. Student's t-tests were used to compare groups using the GraphPad Prism4 program.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2013R1A1A2007071) and by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI16C1085).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by M Agostini

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bishop AL, Hall A. Rho GTPases and their effector proteins. Biochem J 2000; 348(Pt 2): 241–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burridge K, Wennerberg K. Rho and Rac take center stage. Cell 2004; 116: 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim JG, Moon MY, Park SH, Park JB. IκB kinase gamma/nuclear factor-κB-essential modulator (IKKgamma/NEMO) facilitates RhoA GTPase activation, which, in turn, activates Rho-associated KINASE (ROCK) to phosphorylate IKKbeta in response to transforming growth factor TGF-β1. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 1429–1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjoller L, Hall A. Signaling to Rho GTPases. Exp Cell Res 1999; 253: 166–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govek EE, Newey SE, Van Aelst L. The role of the Rho GTPases in neuronal development. Genes Dev 2005; 19: 1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L. RHO GTPASES in neuronal morphogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2000; 1: 173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva JS, Dotti CG. Breaking the neuronal sphere: regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in neuritogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2002; 3: 694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigyi G, Fischer DJ, Sebok A, Marshall F, Dyer DL, Miledi R. Lysophosphatidic acid-induced neurite retraction in PC12 cells: neurite-protective effects of cyclic AMP signaling. J Neurochem 1996; 66: 549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon CY, Moon MY, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Kim JG, Li Y et al. Control of neurite outgrowth by RhoA inactivation. J Neurochem 2012; 120: 684–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black SA, Stys PK, Zamponi GW, Tsutsui S. Cellular prion protein and NMDA receptor modulation: protecting against excitotoxicity. Front Cell Dev Biol 2014; 2: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguzzi A, Baumann F, Bremer J. The prion's elusive reason for being. Annu Rev Neurosci 2008; 31: 439–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorens F, Carulla P, Villa A, Torres JM, Fortes P, Ferrer I et al. PrP(C) regulates epidermal growth factor receptor function and cell shape dynamics in Neuro2a cells. J Neurochem 2013; 127: 124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt C, Peyrin JM, Haik S, Gauczynski S, Leucht C, Rieger R et al. Identification of interaction domains of the prion protein with its 37-kDa/67-kDa laminin receptor. EMBO J 2001; 20: 5876–5886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DC, Rees CG, Duchesne L, Patey SJ, Terry CJ, Turnbull JE et al. Interactions of multiple heparin binding growth factors with neuropilin-1 and potentiation of the activity of fibroblast growth factor-2. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 13457–13464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanata SM, Lopes MH, Mercadante AF, Hajj GN, Chiarini LB, Nomizo R et al. Stress-inducible protein 1 is a cell surface ligand for cellular prion that triggers neuroprotection. EMBO J 2002; 21: 3307–3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielhaupter C, Schatzl HM. PrPC directly interacts with proteins involved in signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 44604–44612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillet-Richard S, Ermonval M, Chebassier C, Laplanche JL, Lehmann S, Launay JM et al. Signal transduction through prion protein. Science 2000; 289: 1925–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt-Ulms G, Legname G, Baldwin MA, Ball HL, Bradon N, Bosque PJ et al. Binding of neural cell adhesion molecules (N-CAMs) to the cellular prion protein. J Mol Biol 2001; 314: 1209–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santuccione A, Sytnyk V, Leshchyns'ka I, Schachner M. Prion protein recruits its neuronal receptor NCAM to lipid rafts to activate p59fyn and to enhance neurite outgrowth. J Cell Biol 2005; 169: 341–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger R, Edenhofer F, Lasmezas CI, Weiss S. The human 37-kDa laminin receptor precursor interacts with the prion protein in eukaryotic cells. Nat Med 1997; 3: 1383–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beraldo FH, Arantes CP, Santos TG, Machado CF, Roffe M, Hajj GN et al. Metabotropic glutamate receptors transduce signals for neurite outgrowth after binding of the prion protein to laminin gamma1 chain. FASEB J 2011; 25: 265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Mange A, Dong L, Lehmann S, Schachner M. Prion protein as trans-interacting partner for neurons is involved in neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival. Mol Cell Neurosci 2003; 22: 227–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs B, Dorner-Ciossek C, Schmalzbauer R, Vassallo N, Herms J, Kretzschmar HA. Prion protein induced signaling cascades in monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2006; 340: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loubet D, Dakowski C, Pietri M, Pradines E, Bernard S, Callebert J et al. Neuritogenesis: the prion protein controls beta1 integrin signaling activity. FASEB J 2012; 26: 678–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleaume-Butaux A, Nicot S, Pietri M, Baudry A, Dakowski C, Tixador P et al. Double-edge sword of sustained ROCK activation in prion diseases through neuritogenesis defects and prion accumulation. PLoS Pathogens 2015; 11: e1005073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Kim JI, Choi EK, Carp RI, Kim YS. A neuronal cell line that does not express either prion or doppel proteins. Neuroreport 2005; 16: 425–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellerbroek SM, Wennerberg K, Burridge K. Serine phosphorylation negatively regulates RhoA in vivo. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 19023–19031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiering D, Hodgson L. Dynamics of the Rho-family small GTPases in actin regulation and motility. Cell Adh Migr 2011; 5: 170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sit ST, Manser E. Rho GTPases and their role in organizing the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 2011; 124(Pt 5): 679–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns MR, Matheson SF, Hu KQ, Delalle I, Caviness VS, Silver J et al. The adhesion signaling molecule p190 RhoGAP is required for morphogenetic processes in neural development. Development 2000; 127: 4891–4903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouns MR, Matheson SF, Settleman J. p190 RhoGAP is the principal Src substrate in brain and regulates axon outgrowth, guidance and fasciculation. Nat Cell Biol 2001; 3: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur WT, Burridge K. RhoA inactivation by p190RhoGAP regulates cell spreading and migration by promoting membrane protrusion and polarity. Mol Biol Cell 2001; 12: 2711–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Mastrianni JA. The prion diseases. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2010; 23: 277–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prusiner SB, DeArmond SJ. Molecular biology and pathology of scrapie and the prion diseases of humans. Brain Pathol 1991; 1: 297–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs GG, Budka H. Prion diseases: from protein to cell pathology. Am J Pathol 2008; 172: 555–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden R, Martins VR, Prado MA, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Brentani RR. Physiology of the prion protein. Physiol Rev 2008; 88: 673–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Regulation of growth cone actin filaments by guidance cues. J Neurobiol 2004; 58: 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau PC. Actin in axons: stable scaffolds and dynamic filaments. Results Probl Cell Differ 2009; 48: 65–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilve S, Difato F, Chieregatti E. Cofilin 1 activation prevents the defects in axon elongation and guidance induced by extracellular alpha-synuclein. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 16524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi K. Roles of cofilin in development and its mechanisms of regulation. Dev Growth Differ 2015; 57: 275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause KH, Lambeth D, Kronke M. NOX enzymes as drug targets. Cell Mol Life Sci 2012; 69: 2279–2282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KP, Kuhn TB, Bamburg JR. Cellular prion protein: a co-receptor mediating neuronal cofilin-actin rod formation induced by beta-amyloid and proinflammatory cytokines. Prion 2014; 8: 375–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graner E, Mercadante AF, Zanata SM, Martins VR, Jay DG, Brentani RR. Laminin-induced PC-12 cell differentiation is inhibited following laser inactivation of cellular prion protein. FEBS Lett 2000; 482: 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Rapp J, Martin-Lanneree S, Hirsch TZ, Pradines E, Alleaume-Butaux A, Schneider B et al. A PrP(C)-caveolin-Lyn complex negatively controls neuronal GSK3beta and serotonin 1B receptor. Sci Rep 2014; 4: 4881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auer M, Schweigreiter R, Hausott B, Thongrong S, Holtje M, Just I et al. Rho-independent stimulation of axon outgrowth and activation of the ERK and Akt signaling pathways by C3 transferase in sensory neurons. Front Cell Neurosci 2012; 6: 43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel N, Ratzka A, Brinkmann H, Klimaschewski L, Grothe C, Claus P. Analysis of the fibroblast growth factor system reveals alterations in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e31202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur WT, Petch LA, Burridge K. Integrin engagement suppresses RhoA activity via a c-Src-dependent mechanism. Curr Biol 2000; 10: 719–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara H, Mueller SC, Nomizu M, Yamada Y, Yeh Y, Chen WT. Activation of beta1 integrin signaling stimulates tyrosine phosphorylation of p190RhoGAP and membrane-protrusive activities at invadopodia. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 9–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV. Rapid recruitment of p120RasGAP and its associated protein, p190RhoGAP, to the cytoskeleton during integrin mediated cell-substrate interaction. Oncogene 1998; 17: 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon CY, Kim HJ, Morii H, Mori N, Settleman J, Lee JY et al. Neurite outgrowth from PC12 cells by basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) is mediated by RhoA inactivation through p190RhoGAP and ARAP3. J Cell Physiol 2010; 224: 786–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang P, Gesbert F, Delespine-Carmagnat M, Stancou R, Pouchelet M, Bertoglio J. Protein kinase A phosphorylation of RhoA mediates the morphological and functional effects of cyclic AMP in cytotoxic lymphocytes. EMBO J 1996; 15: 510–519. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forget MA, Desrosiers RR, Gingras D, Beliveau R. Phosphorylation states of Cdc42 and RhoA regulate their interactions with Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor and their extraction from biological membranes. Biochem J 2002; 361(Pt 2): 243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko E, Sabouri-Ghomi M, Pertz O, Kim C, Gutierrez E, Machacek M et al. Protein kinase A governs a RhoA-RhoGDI protrusion-retraction pacemaker in migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol 2011; 13: 660–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftopoulou M, Hall A. Cell migration: Rho GTPases lead the way. Dev Biol 2004; 265: 23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shmerling D, Hegyi I, Fischer M, Blattler T, Brandner S, Gotz J et al. Expression of amino-terminally truncated PrP in the mouse leading to ataxia and specific cerebellar lesions. Cell 1998; 93: 203–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann F, Tolnay M, Brabeck C, Pahnke J, Kloz U, Niemann HH et al. Lethal recessive myelin toxicity of prion protein lacking its central domain. EMBO J 2007; 26: 538–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BH, Lee HG, Choi JK, Kim JI, Choi EK, Carp RI et al. The cellular prion protein (PrPC) prevents apoptotic neuronal cell death and mitochondrial dysfunction induced by serum deprivation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 2004; 124: 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI et al. Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol 1987; 61: 3688–3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.