Abstract

In mammals, oocytes are arrested at the diplotene stage of meiosis I until the pre-ovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge triggers meiotic resumption through the signals in follicular granulosa cells. In this study, we show that the estradiol (E2)-estrogen receptors (ERs) system in follicular granulosa cells has a dominant role in controlling oocyte meiotic resumption in mammals. We found that the expression of ERs was controlled by gonadotropins under physiological conditions. E2-ERs system was functional in maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest by regulating the expression of natriuretic peptide C and natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPPC/NPR2), which was achieved through binding to the promoter regions of Nppc and Npr2 genes directly. In ER knockout mice, meiotic arrest was not sustained by E2 in most cumulus–oocyte complexes in vitro and meiosis resumed precociously in pre-ovulatory follicles in vivo. In human granulosa cells, similar conclusions are reached that ER levels were controlled by gonadotropins and E2-ERs regulated the expression of NPPC/NPR2 levels. In addition, our results revealed that the different regulating patterns of follicle-stimulating hormone and LH on ER levels in vivo versus in vitro determined their distinct actions on oocyte maturation. Taken together, these findings suggest a critical role of E2-ERs system during oocyte meiotic progression and may propose a novel approach for oocyte in vitro maturation treatment in clinical practice.

In mammals, immature oocytes enter a specialized cell cycle (meiosis, which could reduce the number of chromosomes from diploid to haploid) during embryogenesis, but then pause at the diplotene stage of prophase around the time of birth for prolonged periods. In the case of women, oocytes may remain in this arrested state for 40 years or more. Until the puberty, the arrested oocytes in Graafian follicles resume meiosis in response to the pre-ovulatory luteinizing hormone (LH) surge stimulation, and then the mature oocytes (eggs) are ovulated into the oviduct to await fertilization. Oocytes arrested at the diplotene stage, which have an intact nuclear envelope are referred to as germinal vesicle (GV)-stage oocytes, and nuclear envelope dissolved (meiosis resumed) oocytes are referred to as GV breakdown (GVB)-stage oocytes.

It has been widely accepted that the key inhibitory substance for maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest in Graafian follicles is from follicular somatic cells ever since the experiments in the 1930s.1 Until recently, it is reported that this inhibitory signal in follicular mural granulosa cells (MGCs) is natriuretic peptide C (NPPC, also known as CNP), which could promote cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production through binding to its receptor natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPR2) in cumulus cells (CCs).2, 3, 4 Cyclic GMP then diffuses into the oocyte via the large network of gap junction communications5 and inhibits phosphodiesterase 3A (PDE3A) activity, thereby suppressing the hydrolysis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)6, 7 and maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest by activating protein kinase A.8, 9, 10 Although the well understood downstream signaling, little is known about the events upstream of NPPC and NPR2 that maintain oocyte meiotic arrest. A recent study in the ovary suggests a potential role for LH in decreasing NPPC secretion and NPR2 guanylyl cyclase activity to promote meiotic resumption,11, 12, 13, 14 but molecular signaling that directly controls the expression of NPPC/NPR2 system is totally unknown.

Estradiol (E2), which is primarily produced by pre-ovulatory follicles under the influence of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH),15 has a critical role in the development and maintenance of female reproductive organs. E2 exerts its effects by binding to its nuclear receptor proteins (estrogen receptors (ERs), including ERα and ERβ, whose corresponding genes are named as Esr1 and Esr2), which display cell-dependent and promoter context-dependent transcriptional activities. Adult mice lacking ERα (ERα knockout (αERKO)) are infertile and possess ovaries that exhibit invariably elevated steroid synthesis and multiple hemorrhagic/cystic follicles.16 In contrast, adult mice lacking ERβ (βERKO) are subfertile and possess ovaries that show consistently reduced numbers of growing follicles and corpora lutea.17 Although dozens of evidences have shown that E2-ERs system has a vital role during folliculogenesis by enhancing the actions of FSH,18, 19, 20, 21 little is known about the functional role of E2-ERs system during the process of oocyte maturation.

Female fertility in mammals depends on the coordinated development of ovarian follicles and oocytes, which is regulated by two pituitary derived gonadotrophins (FSH and LH) during each reproductive cycle.22 It is widely accepted that LH is primarily responsible for the stimulation of meiotic resumption and the subsequent ovulation in pre-ovulatory follicles, and FSH stimulates the growth and development of the next wave of follicles.23 Based on this concept, FSH and LH are widely used in human and livestock to control ovarian superovulation and in vitro fertilization (IVF).24, 25, 26 Thus, understanding the mechanisms of FSH and LH controlling follicular development and oocyte maturation is critical for improving the effectiveness of assisted reproduction techniques (ARTs) in clinical applications. In addition, series of studies have indicated that FSH alone is sufficient to induce oocyte maturation in vitro,27, 28, 29, 30 which is contradictory with that in vivo. However, the related mechanisms are poorly understood.

In this study, our results revealed the novel role of E2-ERs in regulating oocyte meiotic resumption in mammals. We provided the experimental evidences showing that E2 and its nuclear receptors in granulosa cells, which are regulated by gonadotropins, govern oocyte meiotic progression by directly regulating Nppc/Npr2 gene transcription in mouse and human ovaries. Elucidation of the physiological role of E2-ERs during the process of oocyte maturation will provide potential therapeutic targets in the treatment of oocyte in vitro maturation (IVM) in clinical applications.

Results

Gonadotropins control the expression of ERs in vivo

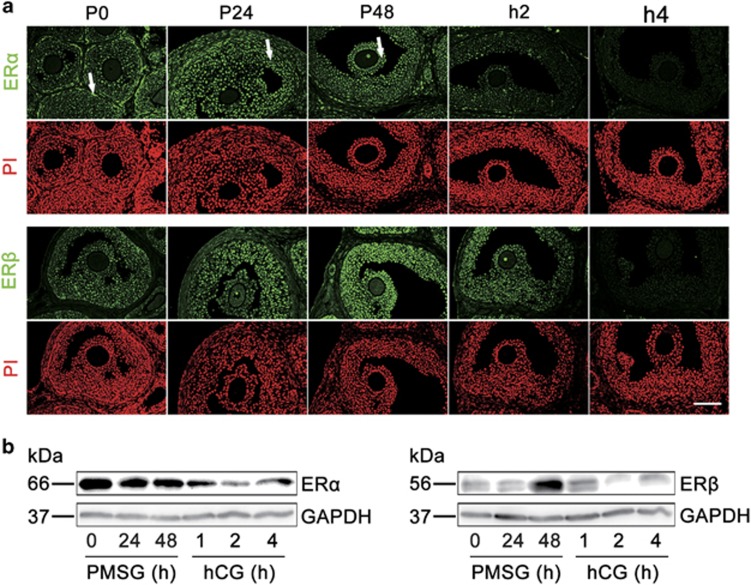

To explore the role of E2 during oocyte meiotic progression under physiological conditions, we first analyzed the localization of ERα and ERβ in mouse ovaries. Immunofluorescence analysis (Figure 1a) of ovaries revealed that ERα was highly expressed in the theca cells (indicated by arrows in P0) of small follicles, but was also present in the MGCs (indicated by arrows in P24) and CCs (indicated by arrows in P48) of large antral follicles following follicular development by pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin (PMSG) stimulation. In contrast, ERβ was predominantly observed in MGCs and CCs of large antral follicles. The localization of ERα and ERβ in MGCs and CCs was substantiated by the immunohistochemistry analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Gonadotropins control ER levels in mouse ovaries in vivo. (a) Immunofluorescence analysis of ERα and ERβ expression in ovaries. Ovaries were stained for ERα or ERβ (green) and the nuclear marker propidium iodide (PI, red) at the indicated time points after PMSG stimulation followed at 48 h later with hCG. ERα protein was highly expressed in theca cells (indicated by arrows in P0) in small follicles, but also stained in MGCs (indicated by arrows in P24) and CCs (indicated by arrows in P48) of large antral follicles by PMSG stimulation. ERβ staining was predominantly observed in MGCs and CCs in large antral follicles. P, means PMSG, h means hCG. Scale bars: 100 μm. (b) WB data indicating the regulation of gonadotropins on ERα and ERβ levels in ovaries. Ovaries were isolated from 22- to 24-day-old mice stimulated with PMSG followed at 48 h later with hCG as indicated in figures. GAPDH served as a loading control

We next analyzed the variation of ERα and ERβ protein levels in mouse ovaries in respond to gonadotropin stimulation. As shown in Figure 1b, the whole ovarian content of ERα was expressed at a relatively high level after stimulation with PMSG, whereas ERβ levels were significantly elevated after stimulation for 48 h by PMSG. Subsequently, the following human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) significantly decreased the expression of ERα and ERβ protein levels. The results of immunofluorescence analysis also confirmed the regulating patterns of gonadotropins on ERα and ERβ levels (Figure 1a). On the other hand, the levels of NPPC and NPR2 in ovaries regulated by gonadotropins exhibited a similar expression pattern to that of ERα and ERβ (Supplementary Figure S2), indicating a potential role of E2-ERs in maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest.

E2-ERs promote and maintain Nppc/Npr2 levels and oocyte meiotic arrest

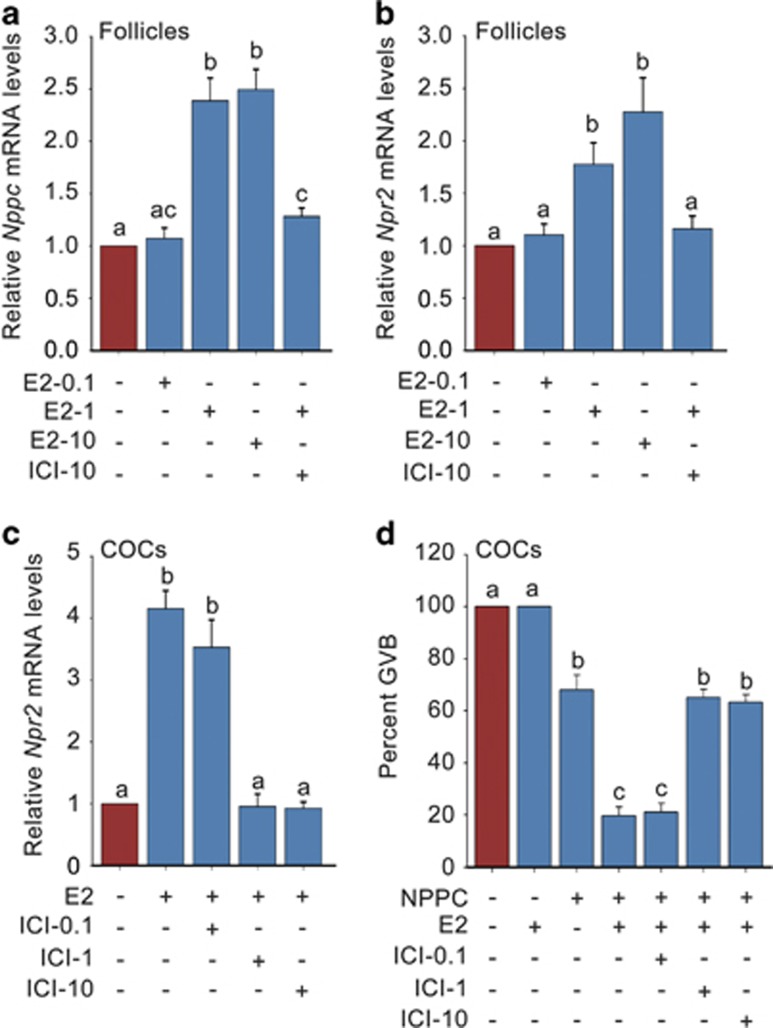

To ascertain the role of E2-ERs system in controlling oocyte meiotic progression and the related mechanisms, we cultured follicles and cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) with E2 and ICI182780 (ICI: a nonselective ERα and ERβ antagonist) in vitro. The results showed that E2 dose-dependently promoted Nppc/Npr2 mRNA levels in follicles (Figures 2a and b) and significantly elevated Npr2 mRNA levels in COCs (Figure 2c). The highest concentration of E2 (10.0 μM) triggered close to 2.5-fold increase in Nppc/Npr2 gene expression in follicles, and 0.1 μM E2 induced a fourfold higher increase in Npr2 levels in COCs. Importantly, the E2-elevated Npr2 levels significantly promoted NPPC-maintained meiotic arrest in COCs after a culture of 24 h (Figure 2d). However, the E2 increased Nppc/Npr2 levels and percentages of meiotic arrested oocytes were completely reversed by ICI either in follicles or in COCs (Figures 2a–d). Therefore, we conclude that E2-ERs act as an important role in maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest by mediating the signaling network between gonadotropins and NPPC/NPR2.

Figure 2.

E2-ERs promote Nppc/Npr2 levels and maintain NPPC-mediated oocyte meiotic arrest. (a and b) Effects of E2 and ICI182780 on Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in follicles. Follicles were cultured in medium containing 0.0 μM (control)–10.0 μM E2 or plus 10 μM ICI182780 (ICI: a nonselective ERα and ERβ antagonist) for 4 h. n=3. (c) Effects of E2 and ICI on Npr2 mRNA levels in COCs. COCs were cultured for 24 h in medium without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2 or plus 0.1–1.0 μM ICI. n=3. (d) Effects of E2 and ICI on NPPC-mediated oocyte meiotic arrest in COCs. COCs were cultured for 24 h and the percentages of oocytes that underwent GVB were determined. E2, 0.1 μM; NPPC, 0.03 μM; ICI, 0.1–1.0 μM. n=4. Data represent the mean±S.E.M. Different letters (a-c) indicate significant differences between groups (P<0.05, ANOVA and Holm–Sidaik test)

ERKO mice exhibit increased percentages of meiotic resumed oocytes

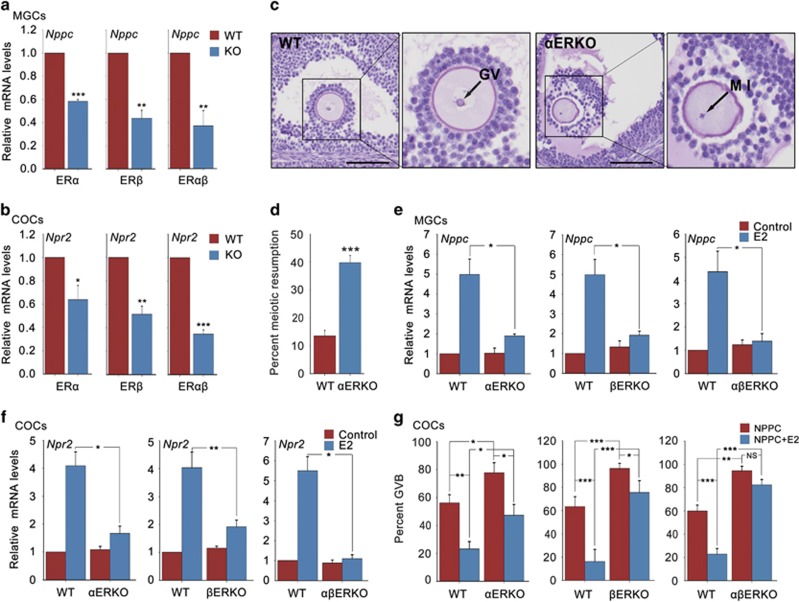

If E2-ERs participate in the maintenance of oocyte meiotic arrest by promoting NPPC/NPR2 expression, then NPPC/NPR2 levels in ERKO mice should be decreased and oocytes within ERKO mice should exhibit a failure of meiotic arrest. To test our hypothesis and to study, which subtype of ERs is required in this process, we measured Nppc/Npr2 mRNA levels in ERKO mice. As expected, the levels of Nppc in MGCs and Npr2 in COCs from αERKO, βERKO and ERα and ERβ double knockout (αβERKO) mouse ovaries were significantly decreased under physiological conditions, when comparing with that in wild-type (WT) mouse ovaries (Figures 3a and b). Thus, ERα and ERβ are both essential for promoting NPPC and NPR2 levels.

Figure 3.

ERKO mouse ovaries show decreased NPPC/NPR2 levels and percentages of meiotic arrested oocytes. (a and b) Expression of Nppc levels in MGCs and Npr2 levels in COCs isolated from 22- to 24-day-old WT and ERKO mouse ovaries. Ovaries were stimulated with PMSG for 46 to 48 h. n=3. (c) A prophase-arrested oocyte (GV) within a large antral follicle of a WT ovary and an oocyte with metaphase I (MI) chromosomes within a large antral follicle of a αERKO ovary. Scale bars: 100 μm. (d) Percentages of oocytes that had resumed meiosis, counted in serial sections of ovaries from WT and αERKO mice. n=9. (e and f) Effects of E2 on Nppc levels in MGCs and Npr2 levels in COCs isolated from WT and ERKO mice. MGCs and COCs were cultured for 24 h in medium without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2. n=3. (g) Effect of E2 on NPPC-maintained oocyte meiotic arrest within COCs isolated from WT and ERKO mice. COCs were incubated in medium containing 0.03 μM NPPC or plus 0.1 μM E2 for 24 h. n=4. Data represent the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (t-test)

We then analyzed the oocyte meiotic progression in ERKO mice. As expected, 39.8±2.6% of oocytes within the large antral follicles of αERKO ovaries by PMSG stimulation had precociously resumed meiosis when comparing with 13.5±2.0% of WT oocytes (Figures 3c and d). However, as most of the follicles in βERKO and αβERKO ovaries cannot develop to the pre-ovulatory stage (Supplementary Figure S4) resulting from the attenuated ovarian responsiveness to FSH/PMSG stimulation,31, 32 additional studies to test our hypothesis under physiological conditions are impossible to perform. Hence, we chose in vitro model as an alternative approach to investigate our hypothesis. As shown in Figures 3e and f, when MGCs and COCs were cultured in vitro, E2 induced approximately four to fivefold higher levels of Nppc and Npr2 mRNA in WT mice, however, the E2-elevated Nppc levels in MGCs were significantly compromised in αERKO mice (close to 1.9-fold) and not observed in βERKO and αβERKO mice. Similarly, the Npr2 mRNA levels promoted by E2 in COCs were remarkably compromised in αERKO and βERKO mice (close to 1.7-fold) and not observed in αβERKO mice. As MGCs has a relative lower NPR2 levels than CCs,33 we also examined Npr2 mRNA levels in MGCs and found a similar Npr2 expression pattern as that in COCs (Supplementary Figure S3). Moreover, when COCs were cultured in vitro, the majority of WT oocytes were maintained at meiotic arrested stage by E2 and NPPC and only 16.2±6.4% to 23.2±5.2% of oocytes resumed meiosis. In comparison, only few of the ERKO oocytes were maintained at meiotic arrested stage by E2 and NPPC, most of the oocytes had underwent GVB (αERKO: 47.4±7.2% βERKO: 75.6±9.3% αβERKO: 82.4±4.6%) (Figure 3g). Collectively, our genetic evidences show that both ERα and ERβ are required for E2 to promote NPPC/NPR2 levels and maintain oocyte meiotic arrest under physiological conditions.

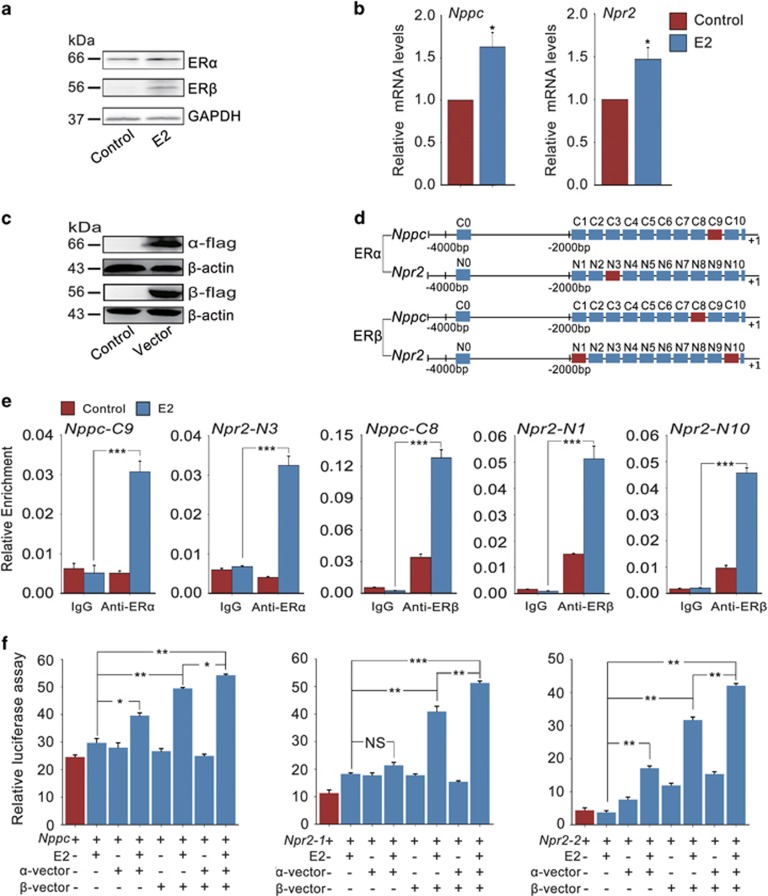

ERs directly regulate Nppc and Npr2 gene transcription

To uncover the potential mechanism how ERs regulate the expression of NPPC/NPR2 during oocyte meiotic progression, a mouse gonadotropin-responsive granulosa cell line (KK1)34 responding to E2 stimulation (Figures 4a and b) was used for chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. Transfection of flag-tagged mouse ERα- and ERβ-vector (α-vector and β-vector) was efficient in KK1 cells (Figure 4c). The DNA fragments that immunoprecipitated with the anti-flag antibody were PCR-amplified with 11 pairs of primers within the 4000-bp regions of Nppc and Npr2 promoter sequences (Figure 4c). Results indicated that ERα binds to the −400 to −200 (C9) and −1600 to −1400 (N3) sequences of Nppc and Npr2 promoters from the transcription start (+1), respectively. In contrast, ERβ binds to the −600 to −400 (C8), −2000 to −1800 (N10) and −200 to 0 (N1) regions of the Nppc and Npr2 promoters, respectively (Figures 4d and e).The putative binding sites of Nppc and Npr2 promoter sequences for ERα and ERβ analyzed in silico were shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

Figure 4.

ERs directly regulate Nppc and Npr2 gene transcription. (a) Expression of ERα and ERβ proteins in KK1 cells in response to E2 stimulation. KK1 cells were treated without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2 for 24 h. GAPDH served as a loading control. (b) Effect of E2 on Nppc and Npr2 levels in KK1 cells. KK1 cells were cultured for 24 h in medium containing 0.1 μM E2 or not (control). n=3. (c) Expression of ERα and ERβ proteins in KK1 cells after transfection with empty vector (control), flag-tagged mouse α-vector or β-vector for 48 h. ERα and ERβ protein levels were assessed using an anti-flag antibody. β-Actin served as a loading control. (d) Schematic diagram of Nppc and Npr2 genome structure. Each rectangle denotes 200 bp. Red rectangles represent the Nppc or Npr2 promoter binding sequences for ERα or ERβ. (e) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the interaction between ERα/ERβ proteins and Nppc/Npr2 promoters in KK1 cells. KK1 cells (transfection with empty vector, flag-tagged mouse α-vector or β-vector) were treated without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2 for 6 h. n=3. (f) The binding of ERα/ERβ to Nppc/Npr2 promoter regions detected by luciferase reporter assay. KK1 cells (transfection with pRL-TK plus flag-tagged mouse α-vector, β-vector or both) were treated without or with 0.1 μM E2 for 24 h. pRL-TK, an internal control plasmid to normalize firefly luciferase activity of the reporter plasmids. Nppc, Npp2-1 or Npr2-2 represent pGL3-basic plasmid containing −2000 to 1 regions of the Nppc gene, −616 to 1 or −2000 to −1260 regions of the Npr2 gene, respectively. n=4. Data represent the mean±S.E.M. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 (t-test)

To further confirm the interaction between ERα/ERβ proteins and Nppc/Npr2 promoters, a dual-luciferase assay using reporter constructs containing the C8, C9, N1, N3 and N10 loci of Nppc or Npr2 promoter was performed (Figure 4f). Transfection of mouse α-vector, β-vector, in particular, co-transfection of both α-vector and β-vector significantly enhanced luciferase activity in response to E2 treatment, demonstrating that ERα and ERβ collaboratively regulate NPPC/NPR2 levels through binding to the promoter regions of Nppc and Npr2 genes directly.

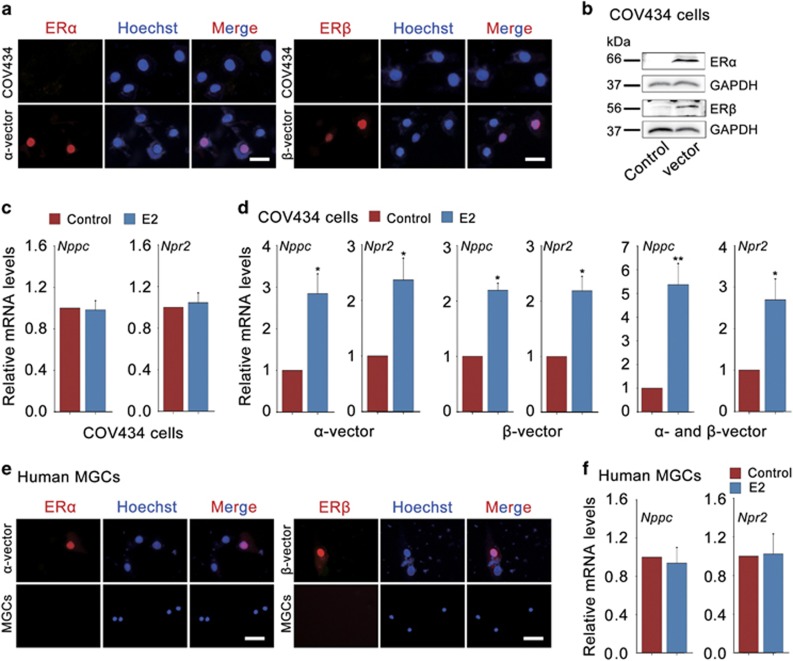

E2-ERs promote Nppc and Npr2 levels in human granulosa cells

To investigate whether E2-ERs are involved in the progress of human oocyte meiosis, we used a human granulosa cell line (COV434), which keeps most of the biological characteristics of human granulosa cells.35 Results indicated that as the deficiency of ER proteins (Figures 5a and b), E2 failed to promote Nppc/Npr2 levels in COV434 cells (Figure 5c). Interestingly, when ERα and ERβ levels were over expressed in COV434 cells by transfecting with myc-tagged human α-vector or β-vector (Figures 5a and b), E2 significantly promoted Nppc/Npr2 levels (Figure 5d), COV434 cells transfected with empty vector served as a control (Supplementary Figure S6). Therefore, we conclude that E2-ERs also have a critical role in regulating Nppc/Npr2 levels in human granulosa cells.

Figure 5.

E2-ERs promote Nppc and Npr2 levels in human granulosa cells. (a) Expression of ERα and ERβ (red) in COV434 cells (upper) or COV434 cells after transfection with myc-tagged human α-vector or β-vector for 48 h (under). The nuclei were stained as blue by Hoechst. Scale bars: 25 μm. (b) WB analysis of ERα and ERβ protein levels in COV434 cells. COV434 cells were transfected with empty vector (control), myc-tagged human α-vector or β-vector for 48 h. GAPDH served as a loading control. (c) E2 failed to promote Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in COV434 cells. COV434 cells were cultured in medium without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2 for 24 h. Data represent the mean±S.E.M. n=3. (d) E2 increased Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in COV434 cells after transfection with myc-tagged human α-vector, β-vector or both. COV434 cells were incubated without (control) or with 0.1 μM E2 for 24 h. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 (t-test). Data represent the mean±S.E.M. n=3. (e) Expression of ERα and ERβ (red) in human MGCs. Human MGCs were freshly isolated from ovulatory follicles, which were stimulated with FSH for 10 days, and followed by LH for 36 h. Human MGCs after transfection with myc-tagged human α-vector or β-vector for 48 h served as the corresponding positive control (upper). The nuclei were stained as blue by Hoechst. Scale bars: 25 μm. (f) Effect of E2 on Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in human MGCs. Human MGCs were freshly isolated from ovaries stimulated with FSH for 10 days followed by LH for 36 h and cultured for 24 h in medium containing 0.1 μM E2 or not (control). Data represent the mean±S.E.M. n=3

To study the function of E2-ERs during human oocyte meiotic progression under more physiological conditions, we measured Nppc/Npr2 levels regulated by E2-ERs in human MGCs, which were freshly isolated from ovulatory follicles. As previous reported that human granulosa cells have the most intense staining of ERs in pre-ovulatory follicles before LH surge (when FSH expression is highest) but not detectable ER proteins after LH surge during the menstrual cycle.36 Here we also found no detectable ER proteins in human MGCs from ovulatory follicles, which were simulated with FSH for 10 days and followed by LH for 36 h, thereby E2 failed to maintain Nppc/Npr2 levels (Figures 5e and f), which are similar to the results in mouse (Figures 1,2 and 3). As a result of the limitation of ethics, here we were unable to obtain human MGCs (which have ER staining) stimulated by FSH only. Alternatively, human MGCs after transfection with myc-tagged human α-vector or β-vector for 48 h were used as the corresponding positive control (Figure 5e). Taken together, gonadotropins also control ER levels in human MGCs, which can promote NPPC/NPR2 levels in response to E2 treatment, indicating a potential role for E2-ERs in governing the process of human oocyte maturation.

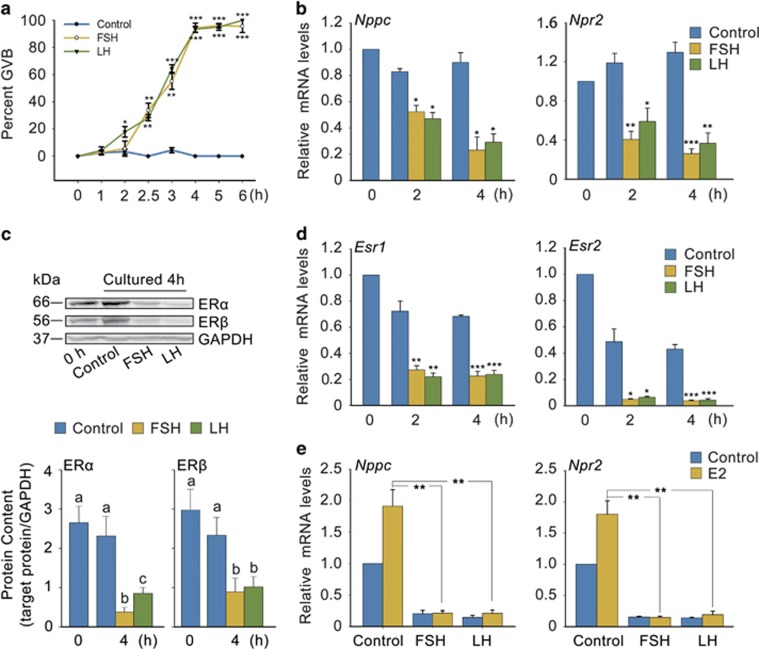

Gonadotropins induce oocyte maturation by suppressing ER levels

To investigate whether E2-ERs are responsible for gonadotropin-induced oocyte maturation, we cultured follicles with FSH and LH in vitro. Both FSH and LH time-dependently promoted oocyte meiotic resumption in follicles, and >90% GVB were completed after only 4 h (Figure 6a; Supplementary Figure S7A). Furthermore, Nppc/Npr2 mRNA levels and ER levels in follicles were time-dependently reduced along with the progress of oocyte meiotic resumption in respond to FSH and LH stimulation, even when E2 was added (Figures 6b–e; Supplementary Figure S7B), which was similar to that LH does in vivo (Figure 1b; Supplementary Figure S2). These results indicated that gonadotropins induce oocyte maturation may by suppressing ER levels, which directly control NPPC and NPR2 levels.

Figure 6.

FSH and LH induce oocyte maturation by downregulating ER levels in vitro. (a) Effects of FSH and LH on oocyte maturation (referred to as GVB) in follicles. Freshly isolated follicles (0 h) were cultured in medium containing FSH or LH for the indicated period of time. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus corresponding control (t-test). n=6. (b) Effects of FSH and LH on Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in follicles cultured for the indicated period of time. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 versus corresponding control (t-test). n=3. (c) FSH and LH decreased ERα and ERβ levels in follicles. GAPDH served as a loading control. Graph shows the density quantification of WB band (normalization of target protein with respect to GAPDH). Bars represent mean of relative abundance, different letters (a-c) indicate significant differences between groups (P<0.05, ANOVA and Holm–Sidak test). (d) FSH and LH decreased Esr1 and Esr2 mRNA levels in follicles. Esr1 and Esr2 are the corresponding gene names of ERα and ERβ. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus corresponding control (t-test). n=3. (e) E2 failed to promote Nppc and Npr2 mRNA levels in follicles primed with FSH or LH for 4 h. **P<0.01 (t-test). n=3. Data represent the mean±S.E.M. FSH, 0.1 IU/ml; LH, 1.0 μg/ml; E2, 1.0 μM

To further confirm our hypothesis, we cultured COCs with FSH in vitro. As shown in Supplementary Figure S7C, FSH significantly promoted oocyte meiotic resumption, which were suppressed by NPPC alone or together with E2. Further results indicated that FSH markedly decreased the expression of Esr1 and Esr2 mRNA levels in COCs (Supplementary Figure S7D), in turn decreasing Nppc and Npr2 levels, even when E2 was added (Supplementary Figure S7E). Effect of LH was not assessed because the deficiency of LH receptor in COCs. Overall, these data suggested that the decrease of ER levels is required for gonadotropins to promote oocyte meiotic resumption.

In view of our previous results (Figure 1; Supplementary Figure S2), here we found that the effect of LH on ER levels, in turn on NPPC/NPR2 levels and oocyte maturation in vitro was similar to that in vivo. Interestingly, expression of ER and NPPC/NPR2 levels and oocyte maturation regulated by FSH in vitro were opposite from that in vivo (Figure 6; Supplementary Figure S7). Therefore, the different effects of FSH on oocyte maturation in vivo versus in vitro are likely result from its opposite regulating patterns on ER levels, reinforcing the physiological significance of E2-ERs governing oocyte meiotic resumption.

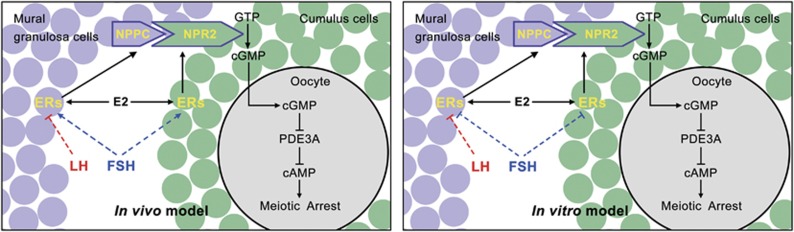

Discussion

It has been known for many years that successful oocyte maturation relies on close communication and cooperation between the oocyte and surrounding granulosa cells, which is regulated by various endocrine, paracrine and autocrine factors. Here we show that the well-known female hormone (E2) and its nuclear receptors in granulosa cells, which are controlled by gonadotropins, have an important role in governing oocyte meiotic resumption in mouse and human ovaries. Figure 7 demonstrates a working model of this process based on our findings presented here and previous studies. Briefly, FSH stimulates the production and expression of E2 and ERs in vivo, E2-ERs then upregulate NPPC and NPR2 levels by directly binding to Nppc and Npr2 promoter regions. The elevated NPPC and NPR2 thus maintain oocyte meiotic arrest by stimulating cGMP production.2, 6, 7 Conversely, pre-ovulatory LH surge decreases ER levels in vivo as FSH and LH do in vitro, thus decreasing NPPC and NPR2 levels, thereby triggers oocyte meiotic resumption. Therefore, E2-ERs act as a vital role during the process of oocyte maturation.

Figure 7.

Model depicting the role of E2-ERs in governing oocyte meiotic resumption in response to gonadotropin stimulation. FSH stimulates ER levels in granulosa cells in vivo, which can directly promote Nppc and Npr2 gene transcription in response to E2 stimulation, thus raising cGMP levels in CCs. Cyclic GMP thereby diffuses into the oocyte through gap junction and inhibits PDE3A activity and cAMP hydrolysis and maintains oocyte meiotic arrest. Conversely, LH decreases ERα and ERβ levels both in vivo and in vitro as FSH does in vitro, in turn decreasing NPPC/NPR2 and cGMP levels, thus triggering the hydrolysis of cAMP by PDE3A and oocyte resumes meiosis

In mammals, oocyte meiotic arrest is important for sustaining the oocyte pool,37 which determines the entire reproductive potential of female over the life span. Recent studies indicate that this blockade in oocyte meiotic cell cycle is under the control of NPPC/NPR2 system in follicular somatic cells.2, 3 In addition, NPPC/NPR2 have a variety of biological roles involved in reproduction, such as fetal development, pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth retardation during pregnancy.38 This system has also been shown to modulate spermatozoa motility, testicular germ cell development and testosterone synthesis in male testis.39, 40 However, less is known about how signaling upstream of NPPC/NPR2 system regulates these processes. In this study, we provide direct evidence indicating that E2-ERs promote Nppc and Npr2 gene transcription by directly binding to their promoter regions. Moreover, mice deficient in either ERα or ERβ showed a substantial decrease in Nppc/Npr2 mRNA levels in vivo, and E2-promoted Nppc/Npr2 mRNA levels in WT mice were significantly compromised in ERKO mice in vitro. Hence, we conclude that E2-ERs are vital upstream regulators of NPPC/NPR2.

Given the indispensable role of NPPC/NPR2 in maintaining oocyte meiotic arrest,2, 3 regulation of NPPC/NPR2 by E2-ERs would be futile under physiological conditions if meiotic progression were not affected in ERKO mice. Indeed, oocytes within Graafian follicles of αERKO mice exhibited precocious gonadotropin-independent meiotic resumption. However, additional studies to test our hypothesis under physiological conditions are difficult to perform because ovaries of ERKO mice exist in a severely abnormal hormonal environment and show impaired development.41 This is particularly true for βERKO mice because oocyte growth, follicular development and ovarian response to gonadotropins are seriously attenuated in these mice.31, 32 Consistent with these studies, we find that the majority of follicles from βERKO and αβERKO mice stimulated by PMSG failed to develop to the pre-ovulatory stage, as manifested by reduced ovarian volume, weight and numbers of large antral follicles and isolated COCs (Supplementary Figure S4). As an alternative approach, COCs were used to explore the function of ERs during oocyte maturation, results indicate that meiotic arrest maintained by NPPC alone or together with E2 in WT COCs were remarkably compromised in αERKO, especially in βERKO and αβERKO COCs in vitro. Therefore, we conclude that ERβ is critical for FSH-stimulated oocyte growth and follicular development, and both ERα and ERβ are essential for maintaining NPPC/NPR2-mediated oocyte meiotic arrest.

Ovulation of a fertilizable egg involves in successful follicular development and oocyte meiotic resumption, which are regulated by FSH and LH.22, 42 Inappropriate follicular development and oocyte maturation may cause reproductive disorders, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome or premature ovarian failure. Here we show that FSH promotes expression of ER levels in follicular granulosa cells accompanying with E2 synthesis,31, 43 E2-ERs then promote NPPC/NPR2 levels by binding to Nppc and Npr2 promoter regions and maintain oocyte meiotic arrest. On the other hand, E2 enhances FSH-induced granulosa cell proliferation, maturation of the whole follicle to a pre-ovulatory state and the LH signaling pathway to expel a healthy oocyte.31, 44 In addition, the elevated NPPC/NPR2 by E2-ERs can stimulate pre-antral and early antral follicles develop to the pre-ovulatory stage.45 By contrast, LH significantly decreases ER levels, thus decreasing NPPC/NPR2 levels and inducing oocyte maturation. Interestingly, FSH also induces meiotic resumption by suppressing ER levels in vitro. Therefore, we conclude that E2-ERs are key regulators mediating gonadotropin-controlled follicular development and oocyte meiotic resumption.

This study answers a controversial issue about the different effects of FSH on oocyte maturation in vivo versus in vitro. It is reported that FSH is primarily responsible for the development of pre-antral follicles and selection of dominant follicles under physiological conditions.23 However, series of studies have indicated that FSH alone is sufficient to induce oocyte maturation in vitro,27, 28, 29, 30 which is contradictory to in vivo situation. Our results that FSH could induce meiotic resumption in follicles and COCs also confirm the functional role of FSH in promoting oocyte maturation (Figure 6; Supplementary Figure S7). We then provide direct evidences that FSH promotes oocyte maturation in vitro by decreasing ER levels as LH does, implying that LH has no bias, whereas FSH has opposite regulating patterns toward to ER levels in vivo versus in vitro. Therefore, we hypothesize that the different effects of FSH on oocyte maturation in vivo versus in vitro may result from its opposite regulating patterns on ER levels, confirming the significant role of E2-ERs during the process of oocyte maturation. However, additional studies are required to explore the exact molecular mechanisms by which ER proteins are regulated.

In human, immature oocytes in pre-ovulatory follicles can experience IVM and IVF, thus initiating pregnancy.46, 47 As a result of the advantages of having a lower risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome,46 the IVM procedure is more and more favored by infertility patients. Here our results indicate that gonadotropins induce oocyte maturation by decreasing ERs-controlled NPPC/NPR2 levels in mice. Moreover, we find that E2-ERs also control NPPC/NPR2 expression and LH decreases ER levels in human MGCs. Considering previous reports that pre-ovulatory LH/hCG surge decreases NPPC secretion in human follicular fluid,11 we hypothesize that the E2-ERs system may also control the resumption of human oocyte meiosis in response to gonadotropin stimulation by regulating NPPC and NPR2 levels. This may provide a novel approach for oocyte IVM treatment in clinical practice.

In conclusion, this study identifies a potential role of E2-ERs in controlling oocyte meiotic resumption in mouse and human ovaries by linking the signaling networks between gonadotropins and NPPC/NPR2. These findings may not only contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of mammalian oocyte and follicular development but also propose a novel approach for the treatment of oocyte IVM in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 female mice obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology (Beijing, China) were used in animal experiments. αERKO16 and βERKO17 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA), as previously described. All animal procedures were approved by the Use Committee of China Agricultural University and performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulatory standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

Human

Human MGCs were obtained from 10 patients, aged 25–40 years, who underwent conventional IVF-embryo transfer or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatments at the Peking University First Hospital, Medical Center of Reproduction and Genetics (Beijing, China). The study was approved by the Peking University First Hospital committee on Human Research, and informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in this study. The purified human MGCs were cultured in M199 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum as previously described.14

Chemicals, hormones and media

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PMSG and hCG were obtained from Sansheng Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Ningbo, China), the concentration of both PMSG and hCG used for each mouse was 5 IU. Medium used for all experiments were obtained from Gibco (Life Technologies, Waltham, CA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Ovaries and follicles were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde, for 48 and 24 h, respectively, dehydrated in ethanol and toluene, embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 5 μm onto APES-treated microscope slides (ZLI-9001, Zhongshan Company, Beijing, China) for immunohistochemistry48 or immunofluorescence staining,49 as previously described. Cells were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, membrane osmosed in 0.1% triton X-100 for 5 min, blocked with 10% normal donkey serum for 1 h. COV434 cells and human MGCs transfected with vectors were treated at adherent state and freshly isolated human MGCs were treated at suspension state. Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were diluted as follows: ERα (sc-542, 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and ERβ (sc-8974, 1:2000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Primary antibodies used for immunofluorescence were diluted as follows: ERα (sc-542, 1:100) and ERβ (ab3576, 1:200; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). An isotype-matched IgG was used as the negative control.

Western blotting (WB)

Total proteins were extracted in tissue and cell lysis solution for WB and immunoprecipitation (CellChip, BJ Biotechnology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) and protein concentration was measured by the BCA protein assay kit as recommended by the manufacturer. WB was performed as previously described.48 GAPDH or β-actin served as a loading control. Primary antibodies used for WB were diluted as follows: ERα (sc-542, 1:200), ERβ (sc-53494, 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and DYKDDDDK (Flag) (AE005, 1:3000; ABclonal, Boston, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted and reverse transcribed to cDNA, and qRT-PCR was performed to analyze gene expression changes as previous description.49 Expression data were normalized to the amount of Gapdh (mus) or β-actin (homo). Each experiment was repeated independently at least three times. Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Isolation and culture of mouse MGCs, COCs and follicles

MGCs and COCs were collected from ovaries of 22- to 24-day-old mice stimulated with 5 IU PMSG for 46–48 h in M199 medium, which also contained 4 mM hypoxanthine to prevent oocyte maturation until they were distributed to experimental groups. Follicles (450–550 μm in size) were isolated in Leibovitz's L-15 medium. Before distributing to the experimental groups, all samples were washed three times with the corresponding culture medium. COCs were cultured for 24 h in M199 medium, supplemented with 0.1 IU/ml FSH, 0.1 μM E2, 0.03 μM NPPC or 0.1–10.0 μM ICI (S1191, Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX, USA) as described in the Results section. MGCs were cultured using a monolayer culture system as described in previous study.50 Follicles were cultured for 0–6 h on an insert (PICMORG50, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) in 35 mm Petri dish with DMEM medium plus 0.1 IU/ml FSH, 1.0 μg/ml LH, 0.1–1.0 μM E2 or 10.0 μM ICI as indicated in the Results section. At culture termination, oocyte maturation was assessed by scoring the released oocytes for GV or GVB after removal of CCs. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis for mRNA or protein analysis. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Oocyte quantification

Ovaries from 22- to 24-day-old ERKO mice stimulated with 5 IU PMSG for 46–48 h were fixed, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned at 5 μm. Meiotic status within Graafian follicles was scored by examining serial sections through the entire ovary and stained with periodic acid/Schiff reagents and Lillie–Mayer hematoxylin. Healthy oocytes in every section were counted and the nucleus was scored only once per oocyte. If an intact nucleus (GV) was observed, it was scored as meiotic arrest. If the GV was no longer present or condensed chromosomes were visible in the oocytes, they were scored as having resumed meiosis. The criteria for classification of follicles were applied as previous reported.51

Plasmids

The cDNA-derived mouse ERα/ERβ and human ERα/ERβ sequences were flag-tagged (mouse) and myc-tagged (human) at the N terminus and generated by PCR. Amplified fragments were cloned into pHAGE-CMV-MCS-PGK puro 3+3tag–anp32a plasmid (mouse, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and phage-6Tag-puro-CMV plasmid (human, Promega). For the luciferase assay, the upstream regions of the Npr2 gene relative to the transcription start site (+1) were divided into two fragments (Npr2-1: −616 to 1; Npr2-2: −2000 to −1260). The upstream regions (−2000 to 1) of the Nppc gene and each fragment of the Npr2 gene were then amplified by PCR using mouse genomic DNA as a template. The amplified fragments were cloned into pGL3-basic plasmid (Promega). PCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Cell culture, transfection and dual-luciferase reporter assay

KK1 cells were grown in DMEM medium containing 10% fetal calf serum and 300 mg/l G418 in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37 °C. COV434 cells were grown in McCoy's 5A medium with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells at a confluence of about 80% on plates were transfected with plasmid DNA using lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium or supplemented with alcohol (vehicle) or 0.1 μM E2 and cultured for additional 6 h or 24 h as described in the Figure legends. Cells were collected for RNA or protein analysis.

For the luciferase assay, KK1 cells (transfection with mouse α-vector, β-vector or both) were maintained in medium supplemented with alcohol (vehicle) or 0.1 μM E2. pRL-TK, an internal control plasmid expressing Renilla (Promega), was co-transfected into cells to normalize firefly luciferase activity of the reporter plasmids. Cells were collected after a culture of 24 h. Luciferase activities were measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Assays were performed at least three times, with each sample in duplicate.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

For the ChIP analysis, KK1 cells (transfection with mouse α-vector, β-vector or both) maintained in medium supplementing with alcohol (vehicle) or 0.1 μM E2 were collected at 6 h, and then washed three times with ice-cold PBS. Cell pellets were lysed in 1% SDS buffer containing a protease inhibitor. Chromatin was sheared by sonication until the average DNA length was about 300–500 bp, as evaluated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Sheared chromatin was diluted in ChIP dilution buffer to a final SDS concentration of 0.1%. Salmon sperm DNA/protein agarose slurry was added to preclear the chromatin solution. One percent of the chromatin fragments were stored at −20 °C to be used later for non-precipitated total chromatin (input) for normalization. Ninety-nine percent of the chromatin fragments were incubated with 3 μg anti-flag antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Normal mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used as a negative control for nonspecific immunoprecipitation. The chromatin–antibody complex was incubated with protein A/G beads for 1 h at 4 °C. The antibody/DNA complex on the agarose beads was collected by centrifugation. Beads were washed with various buffers in the following order: low salt immune complex buffer, high salt immune complex buffer, LiCl immune complex buffer and TE buffer. Beads were suspended in elution buffer, and precipitated protein/DNA complexes were eluted from the antibodies/beads. The resulting protein/DNA complexes were subjected to cross-link reversal in 5 M NaCl at 65 °C for 10 h followed by addition of 0.5 M EDTA, 1 M Tris-HCl and 10 μg/ml proteinase K at 55 °C for 2 h. DNA was purified by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. qRT-PCR was used to detect immunoprecipitated chromatin fragments, as well as input chromatin using primers indicated in Supplementary Table S3.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed at least three times, and results were expressed as the mean±S.E.M. Differences between two groups were analyzed by t-test using SigmaPlot software (Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). For experiment with more than two groups, differences between groups were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). When a significant F ratio was detected by ANOVA, the groups were compared using the Holm–Šidák test. Statistically significant values of P<0.05, P<0.01 and P<0.001 are indicated by one, two and three asterisks in the t-test, respectively. Different letters indicate significant differences between groups (P<0.05) in the ANOVA and Holm–Š idák test.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Hua Zhang (China Agricultural University) for his helpful comments during preparation of this paper and Professor Haibin Wang (Medical College of Xiamen University) for the ChIP technical assistance. We thank Professor Sheng Cui (China Agricultural University) for providing the KK1 cell line and Professor Jing Li (Nanjing Medical University) for providing the COV434 cell line. This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program: 2013CB945501; 2014CB943202; 2014CB138503; 2012CB944701), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371448; 31571540) and Project for Young Scientists of State Key Laboratory of Agrobiotechnology (2015SKLAB4-1).

Author contributions

WL, CW and GX designed research; WL, QX, XW, HW and ZZ performed research; WL, XW, HW, WZ, YY and YZ analyzed data; SW and YX provided human MGCs. ED provided heterozygous αERKO and βERKO mice. WL wrote the manuscript with contributions from CW and GX. All authors have seen and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on Cell Death and Disease website (http://www.nature.com/cddis)

Edited by M Piacentini

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pincus G, Enzmann EV. The comparative behavior of mammalian eggs in vivo and in vitro: I. The activation of ovarian eggs. J Exp Med 1935; 62: 665–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Su YQ, Sugiura K, Xia G, Eppig JJ. Granulosa cell ligand NPPC and its receptor NPR2 maintain meiotic arrest in mouse oocytes. Science 2010; 330: 366–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyosu C, Tsuji T, Yamada K, Kajita S, Kunieda T. NPPC/NPR2 signaling is essential for oocyte meiotic arrest and cumulus oophorus formation during follicular development in the mouse ovary. Reproduction 2012; 144: 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigglesworth K, Lee KB, O'Brien MJ, Peng J, Matzuk MM, Eppig JJ. Bidirectional communication between oocytes and ovarian follicular somatic cells is required for meiotic arrest of mammalian oocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: E3723–E3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sela-Abramovich S, Edry I, Galiani D, Nevo N, Dekel N. Disruption of gap junctional communication within the ovarian follicle induces oocyte maturation. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 2280–2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris RP, Ratzan WJ, Freudzon M, Mehlmann LM, Krall J, Movsesian MA et al. Cyclic GMP from the surrounding somatic cells regulates cyclic AMP and meiosis in the mouse oocyte. Development 2009; 136: 1869–1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari S, Weeks JL 2nd, Hsieh M, Menniti FS, Conti M. Cyclic GMP signaling is involved in the luteinizing hormone-dependent meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Biol Reprod 2009; 81: 595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner K, Livera G, Hinckley M, Trinh K, Storm D, Conti M. Rodent oocytes express an active adenylyl cyclase required for meiotic arrest. Dev Biol 2003; 258: 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinckley M, Vaccari S, Horner K, Chen R, Conti M. The G-protein-coupled receptors GPR3 and GPR12 are involved in cAMP signaling and maintenance of meiotic arrest in rodent oocytes. Dev Biol 2005; 287: 249–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledent C, Demeestere I, Blum D, Petermans J, Hamalainen T, Smits G et al. Premature ovarian aging in mice deficient for Gpr3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 8922–8926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura K, Cheng Y, Kawamura N, Takae S, Okada A, Kawagoe Y et al. Pre-ovulatory LH/hCG surge decreases C-type natriuretic peptide secretion by ovarian granulosa cells to promote meiotic resumption of pre-ovulatory oocytes. Hum Reprod 2011; 26: 3094–3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JW, Zhang M, Shuhaibar LC, Norris RP, Geerts A, Wunder F et al. Luteinizing hormone reduces the activity of the NPR2 guanylyl cyclase in mouse ovarian follicles, contributing to the cyclic GMP decrease that promotes resumption of meiosis in oocytes. Dev Biol 2012; 366: 308–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbert JR, Shuhaibar LC, Edmund AB, Van Helden DA, Robinson JW, Uliasz TF et al. Dephosphorylation and inactivation of NPR2 guanylyl cyclase in granulosa cells contributes to the LH-induced decrease in cGMP that causes resumption of meiosis in rat oocytes. Development 2014; 141: 3594–3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Xie F, Zamah AM, Cao B, Conti M. Multiple pathways mediate luteinizing hormone regulation of cGMP signaling in the mouse ovarian follicle. Biol Reprod 2014; 91: 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrington JH, Moon YS, Armstrong DT. Estradiol-17beta biosynthesis in cultured granulosa cells from hypophysectomized immature rats; stimulation by follicle-stimulating hormone. Endocrinology 1975; 97: 1328–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubahn DB, Moyer JS, Golding TS, Couse JF, Korach KS, Smithies O. Alteration of reproductive function but not prenatal sexual development after insertional disruption of the mouse estrogen receptor gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 11162–11166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, Enmark E, Warner M, Mahler JF et al. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 15677–15682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Vaitukaitis JL, Ross GT. Estrogen and follicle stimulation hormone interactions on follicle growth in rats. Endocrinology 1972; 90: 1492–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adashi EY, Hsueh AJ. Estrogens augment the stimulation of ovarian aromatase activity by follicle-stimulating hormone in cultured rat granulosa cells. J Biol Chem 1982; 257: 6077–6083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang LZ, Adashi EY, Hsuch AJ. Direct enhancement of gonadotropin-stimulated ovarian estrogen biosynthesis by estrogen and clomiphene citrate. Endocrinology 1982; 110: 2219–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel B, Liu YX, Jia XC, Hsueh AJ. Autocrine role of estrogens in the augmentation of luteinizing hormone receptor formation in cultured rat granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 1985; 32: 1038–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards JS. Maturation of ovarian follicles: actions and interactions of pituitary and ovarian hormones on follicular cell differentiation. Physiol Rev 1980; 60: 51–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar TR, Wang Y, Lu N, Matzuk MM. Follicle stimulating hormone is required for ovarian follicle maturation but not male fertility. Nat Genet 1997; 15: 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali A, Sirard MA. The effects of 17beta-estradiol and protein supplement on the response to purified and recombinant follicle stimulating hormone in bovine oocytes. Zygote 2002; 10: 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin P, Bousquet D, Twagiramungu H, Barnes F, Sirard MA. Manipulation of follicular development to produce developmentally competent bovine oocytes. Biol Reprod 2002; 66: 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima I, Okazaki T, Noma N, Nishibori M, Yamashita Y, Shimada M. Sequential exposure of porcine cumulus cells to FSH and/or LH is critical for appropriate expression of steroidogenic and ovulation-related genes that impact oocyte maturation in vivo and in vitro. Reproduction 2008; 136: 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppig JJ. Regulation of cumulus oophorus expansion by gonadotropins in vivo and in vitro. Biol Reprod 1980; 23: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhou B, Yan J, Xu B, Tai P, Li J et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation by protein kinase C is necessary for FSH-induced meiotic resumption in porcine cumulus-oocyte complexes. J Endocrinol 2008; 197: 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Xu B, Zhou B, Zhang C, Yang J, Ouyang H et al. Reducing CYP51 inhibits follicle-stimulating hormone induced resumption of mouse oocyte meiosis in vitro. J Lipid Res 2009; 50: 2164–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assidi M, Richard FJ, Sirard MA. FSH in vitro versus LH in vivo: similar genomic effects on the cumulus. J Ovarian Res 2013; 6: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Yates MM, Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor-beta is critical to granulosa cell differentiation and the ovulatory response to gonadotropins. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 3247–3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmen JM, Couse JF, Elmore SA, Yates MM, Kissling GE, Korach KS. In vitro growth and ovulation of follicles from ovaries of estrogen receptor (ER){alpha} and ER{beta} null mice indicate a role for ER{beta} in follicular maturation. Endocrinology 2005; 146: 2817–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Su YQ, Sugiura K, Wigglesworth K, Xia G, Eppig JJ. Estradiol promotes and maintains cumulus cell expression of natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (NPR2) and meiotic arrest in mouse oocytes in vitro. Endocrinology 2011; 152: 4377–4385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kananen K, Markkula M, Rainio E, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Huhtaniemi IT. Gonadal tumorigenesis in transgenic mice bearing the mouse inhibin alpha-subunit promoter/simian virus T-antigen fusion gene: characterization of ovarian tumors and establishment of gonadotropin-responsive granulosa cell lines. Mol Endocrinol 1995; 9: 616–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Vollmer M, De Geyter M, Litzistorf Y, Ladewig A, Durrenberger M et al. Characterization of an immortalized human granulosa cell line (COV434). Mol Hum Reprod 2000; 6: 146–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwai T, Nanbu Y, Iwai M, Taii S, Fujii S, Mori T. Immunohistochemical localization of oestrogen receptors and progesterone receptors in the human ovary throughout the menstrual cycle. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 1990; 417: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homer H, Gui L, Carroll J. A spindle assembly checkpoint protein functions in prophase I arrest and prometaphase progression. Science 2009; 326: 991–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T, Stepan H. C-type natriuretic peptide in reproduction, pregnancy and fetal development. J Endocrinol 2004; 180: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middendorff R, Davidoff MS, Behrends S, Mewe M, Miethens A, Muller D. Multiple roles of the messenger molecule cGMP in testicular function. Andrologia 2000; 32: 55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DH, Zhang SW, Zhao H, Zhang L. The role of C-type natriuretic peptide in rat testes during spermatogenesis. Asian J Androl 2011; 13: 275–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couse JF, Hewitt SC, Bunch DO, Sar M, Walker VR, Davis BJ et al. Postnatal sex reversal of the ovaries in mice lacking estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Science 1999; 286: 2328–2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palermo R. Differential actions of FSH and LH during folliculogenesis. Reprod Biomed Online 2007; 15: 326–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis SR, Burger HG, Robertson DM, Farnworth PG, Carson RS, Krozowski Z. Pregnant mare's serum gonadotropin stimulates inhibin subunit gene expression in the immature rat ovary: dose response characteristics and relationships to serum gonadotropins, inhibin, and ovarian steroid content. Endocrinology 1988; 123: 2399–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroo BJ, Rodriguez KF, Couse JF, Hamilton KJ, Collins JB, Grissom SF et al. Estrogen receptor beta is required for optimal cAMP production in mouse granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 2009; 23: 955–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Cheng Y, Kawamura K, Takae S, Hsueh AJ. C-type natriuretic peptide stimulates ovarian follicle development. Mol Endocrinol 2012; 26: 1158–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EM, Song HS, Lee DR, Lee WS, Yoon TK. In vitro maturation of human oocytes: its role in infertility treatment and new possibilities. Clin Exp Reprod Med 2014; 41: 41–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trounson A, Wood C, Kausche A. In vitro maturation and the fertilization and developmental competence of oocytes recovered from untreated polycystic ovarian patients. Fertil Steril 1994; 62: 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZP, Mu XY, Guo M, Wang YJ, Teng Z, Mao GP et al. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling participates in the maintenance of the primordial follicle pool in the mouse ovary. J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 8299–8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Teng Z, Li G, Mu X, Wang Z, Feng L et al. Cyclic AMP in oocytes controls meiotic prophase I and primordial folliculogenesis in the perinatal mouse ovary. Development 2015; 142: 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KB, Zhang M, Sugiura K, Wigglesworth K, Uliasz T, Jaffe LA et al. Hormonal coordination of natriuretic peptide type C and natriuretic peptide receptor 3 expression in mouse granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 2013; 88: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen T, Peters H. Proposal for a classification of oocytes and follicles in the mouse ovary. J Reprod Fertil 1968; 17: 555–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.