Abstract

Although dual HER-2 blockade treatment could offer greater clinical efficacy in breast cancer, the risk of severe toxicities of special interest related to this combined regimen in breast cancer remained unknown. We systematically searched public databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane library) to identify relevant studies that comparing anti-HER2 monotherapy (lapatinib or trastuzumab or pertuzumab) with dual HER-2 blockade treatment (pertuzumab plus trastuzumab or trastuzumab plus lapatinib) in breast cancer. A total of 11,941 breast cancer patients from 9 trials were included for analysis. Meta-analysis showed that dual HER2 blockade treatment significantly increased the risk of severe diarrhea (OR 2.52, p<0.001) and treatment discontinuation (OR 1.52, p=0.014), but not for severe rash (OR 1.06, p=0.81), liver toxicities (OR 1.16, p=0.28), CHF (OR 1.46, p=0.09), LVEF decline (OR 1.09, p=0.40) and FAEs (OR 0.97, p=0.91). Similar results were observed in sub-group analysis according to anti-HER2 regimens in terms of severe diarrhea and treatment discontinuation. Additionally, trastuzumab plus lapatinib significantly increased the risk of LVEF decline in comparison with lapatinib alone (OR 1.48, p=0.002). Our analysis indicated that dual anti-HER2 blockade treatment significantly increased the risk of developing severe diarrhea and treatment discontinuation in comparison with anti-HER2 monotherapy. These were no evidence of an increased risk of fatal adverse events with dual-HER2 blockade treatment.

Keywords: dual Her-2 blockade, Her2, adverse events, breast cancer, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 15-20% of all breast cancers (HER2-positive) have human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) protein overexpression resulting in a more aggressive phenotype and worse outcome [1–3]. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) superfamily is composed of four transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptors containing HER1, HER2, HER3, and HER4, which plays a critical role in cellular growth and proliferation [4]. HER2 is considered as an orphan receptor because it has no known ligand, and it could constitutively activate signaling pathways through ligand-independent dimerization [5]. As a result, molecular targeting of the HER2 receptor and its family members have emerged as attractive candidates for anticancer therapy [6]. Currently, two anti-HER2 agents, including humanized monoclonal antibody trastuzumab [7, 8] and the small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor lapatinib [9], have been approved for use in the HER2-positive breast cancer. However, despite these treatment advances, most of HER2-positive breast cancer would eventually progress due to intrinsic and acquired HER2 agent resistance, highlighting the need to develop novel agents and combination strategies to overcome resistance.

During the past decade, a dual targeting approach by combination of two anti-HER2 agents has been investigated in several large randomized controlled trials [10]. In fact, dual anti-HER2 therapy has been proven to improve clinical outcomes of metastatic HER2 positive breast cancer though to be refractory to trastuzumab alone, which lead to the approval of pertuzumab for the treatment of HER2 positive breast cancer [11]. In addition, it has been found that dual anti-HER2 treatments almost double the rates of pathologic complete response in comparison with anti-HER2 therapy alone in the neoadjuvant setting [12, 13]. However, the safety profile of dual anti-HER2 blockade treatment remains undetermined. As a result, we perform this systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether the dual anti-HER2 treatment would increase the risk of severe (grade 3 and 4) toxicities of special interest in breast cancer when compared to anti-HER2 monotherapy.

RESULTS

Search results

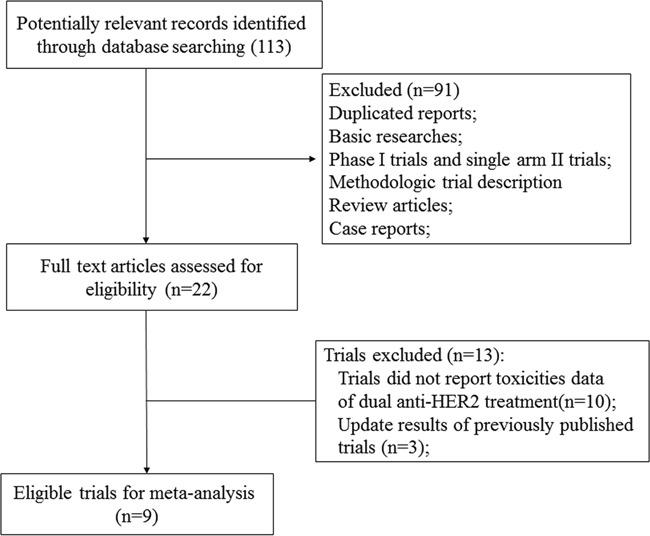

As shown in Figure 1, 22 potentially eligible trials were retrieved for full-text evaluation. The reasons for study exclusion were illustrated in Figure 1. A total of twelve trials were included for analysis [11, 12, 14–23]. Three trials were up-date results of previously published trials [16, 17, 21] and thus nine trials were finally included in this systematic review. (Figure 1) The baseline characteristics of the trials were listed in Table 1. A total of 11,701 HER2 positive breast cancer patients were included in the present study. A rough assessment of the included trials was carried out by using Jadad scale. The quality of the nine trials was high, two trials had a Jadad score of 5 [11, 15], and seven trials had a Jadad score of 3 [12, 14, 18–20, 22, 23].

Figure 1. Studies eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of nine included trials for analysis.

| Authors | Year | Phase | Treatment line | Total patients | Treatment regimens | Median age | Duration of anti-HER2 treatment | No. for analysis | Jadad Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piccart-Gebhart M.et al | 2016 | III | adjuvant | 8381 | L 750mg daily +T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+CT | 51 | 52weeks | 2061 | 3 |

| T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)-L 750mg daily | 51 | 12weeks-34weeks | 2076 | ||||||

| L 750mg daily +CT | 51 | 52weeks | 2057 | ||||||

| T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+CT | 51 | 52weeks | 2076 | ||||||

| Swain S.M. et al(CLEOPATRA) | 2015 | III | metastatic | 808 | P 420mg/kg q.3.w (loading 840mg/kg)+T 6mg/kg q.3.w (loading 8mg/kg) | NR | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 369 | 5 |

| T 6mg/kg q.3.w (loading 8mg/kg)+docetaxel | NR | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 335 | ||||||

| Bonnefoi H. et al | 2015 | II | Neoadjuvant | 128 | L 1000mg daily+ CT | 49.9 | 12weeks | 23 | 3 |

| T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+CT | 47 | 12weeks | 53 | ||||||

| L1000mg daily +T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg +CT | 49.4 | 12weeks | 52 | ||||||

| Robidoux A. et al (NSABP B-41) | 2013 | III | neoadjuvant | 529 | T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg) | NR | 12weeks | 178 | 3 |

| L 1250mg daily | NR | 12weeks | 173 | ||||||

| T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+L 750mg daily | NR | 12weeks | 173 | ||||||

| Guarneri V. et al (CHER-LOB) | 2012 | IIb | neoadjuvant | 121 | T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+CT | 50 | 26weeks | 36 | 3 |

| L 1500mg daily+ CT | 49 | 26weeks | 39 | ||||||

| L 100mg daily +T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+CT | 49 | 26weeks | 46 | ||||||

| Gianni L. et al (NeoSphere) | 2012 | II | neoadjuvant | 417 | T 6mg/kg q.3.w (loading 8mg/kg)+docetaxel | 50 | 12weeks | 107 | 3 |

| P 420mg/kg q.3.w (loading 840mg/kg)+T 6mg/kg q.3.w (loading 8mg/kg) +docetaxel | 50 | 12weeks | 107 | ||||||

| P 420mg/kg q.3.w (loading 840mg/kg)+T 6mg/kg q.3.w (loading 8mg/kg) | 49 | 12weeks | 108 | ||||||

| P 420mg/kg q.3.w (loading 840mg/kg)+docetaxel | 49 | 12weeks | 94 | ||||||

| Baselga J. et al(CLEOPATRA) | 2012 | III | metastatic | 806 | T 6mg/kg q3w (loading 8 mg/kg)+docetaxel | 54 | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 396 | 5 |

| P 420mg q.3.w (loading 840mg) +T 6mg/kg q3w (loading 8 mg/kg) +docetaxel | 54 | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 408 | ||||||

| Baselga J. et al(NeoALTTO) | 2012 | III | Neoadjuvant | 455 | L 1500mg daily+paclitaxel | 50 | 18 weeks | 154 | 3 |

| T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg)+paclitaxel | 49 | 18 weeks | 149 | ||||||

| L1000mg daily+T 2mg/kg (loading 4mg/kg)+paclitaxel | 50 | 18 weeks | 152 | ||||||

| Blackwell K.L. et al | 2010/2012 | III | metastatic | 296 | L1,000mg daily | 51 | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 146 | 3 |

| L1.000mg daily+ T 2mg/kg weekly (loading 4mg/kg) | 52 | until progression or unacceptable toxicity | 149 |

Abbreviation: L, lapatinib; T, trastuzumab; P, pertuzumab; CT, chemotherapy.

Heterogeneity

No observed heterogeneity for grade ≥3 AEs of diarrhea, liver toxicities and CHF, LVEF decline and FAEs was found (Table 2). Therefore, we pooled the risk of severe AEs related to dual anti-HER2 agents by using fixed-effect model, excepting for AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation and grade ≥3 rash.

Table 2. Peto odds ratio of adverse events related to dual anti-HER2 treatment.

| Adverse outcome (grade ≥3) | Trials (n) | No. of patients (n) | I2 | Peto Odds Ratio (95%CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual anti-HER2 agents, Events/total | Anti-HER2 monotherapy,Events/total | |||||

| Diarrhea | 9 | 557/3649 | 431/5992 | 49% | 2.52(95%CI: 2.20-2.89) | <0.001 |

| Rash | 9 | 196/3649 | 238/5992 | 61% | 1.06 (95%CI:0.67-1.68) | 0.81 |

| Liver toxicities | 6 | 100/2723 | 168/5115 | 43% | 1.16 (95%CI:0.89-1.50) | 0.28 |

| CHF | 9 | 42/3649 | 47/5992 | 46% | 1.46(95%CI: 0.94-2.26) | 0.09 |

| LVEF decline | 9 | 209/3649 | 296/5992 | 49% | 1.09(95%CI:0.90-1.31) | 0.40 |

| AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation | 9 | 681/3649 | 684/5992 | 74% | 1.52(95%CI: 1.09-2.12) | 0.014 |

| FAEs | 9 | 28/3649 | 39/5992 | 0% | 0.97(95%CI: 0.59-1.59) | 0.91 |

I2≥50% suggests high heterogeneity across studies.

Abbreviation: CHF, congestive heart failure, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; FAEs, Fatal adverse events.

AEs reported in trials and pooled effects

Diarrhea

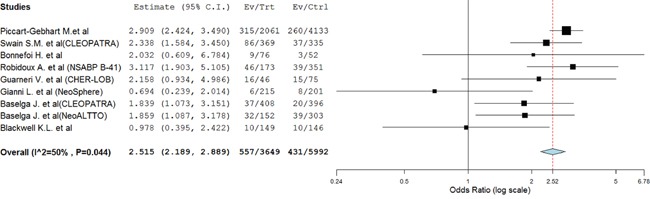

A total of 988 severe diarrhea were reported in the trials; 557 in dual anti-HER2 agent arms and 431 in control arms, yielding an OR of severe diarrhea of 2.52(95%CI: 2.20-2.89, P<0.001) (Table 2, Figure 2). Sub-group analysis also found that trastuzumab combined with lapatinib significantly increased the risk of severe diarrhea in comparison with trastuzumab (OR 6.42, 95%CI: 5.29-7.79, p<0.001) or lapatinib alone (OR 1.33, 95%CI: 1.14-1.55, p<0.001, respectively), and pertuzumab combined with trastuzumab also was associated with a significantly increased risk of severe diarrhea in comparison with trastuzumab alone (OR 2.03, 95%CI: 1.50-3.15, p<0.001, Table 3).

Figure 2. Fixed-effect Model of odds ratio (95%CI) of severe diarrhea associated with dual anti-HER2 agents versus anti-HER2 monotherapy.

Table 3. Subgroup analyses of risk for severe adverse toxicities of special interest from dual anti-HER2 treatment.

| Type of anti-HER2 therapy | No. of trials | Dual anti-HER2 treatment | Monotherapy | Peto OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diarrhea | Total | Diarrhea | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 418 | 2484 | 36 | 2492 | 6.42 (5.29-7.79) | <0.001 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 428 | 2633 | 330 | 2592 | 1.33(1.14-1.55) | <0.001 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 129 | 992 | 61 | 838 | 2.03(1.50-3.15) | <0.001 |

| Rash | Total | Rash | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 117 | 2484 | 15 | 2492 | 4.88 (3.45-6.90) | <0.001 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 150 | 2633 | 189 | 2592 | 0.76(0.61-0.95) | 0.016 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 47 | 992 | 20 | 838 | 2.09(1.27-3.44) | 0.004 |

| Liver toxicities | Total | Liver toxicities | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 100 | 2484 | 33 | 2492 | 2.83(2.00-4.00) | <0.001 |

| T+L versus L | 5 | 100 | 2484 | 131 | 2446 | 0.74(0.56-0.96) | 0.024 |

| P+T versus T | 1 | 0 | 215 | 3 | 107 | 0.07(0.004-1.35) | - |

| CHF | Total | CHF | total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 24 | 2484 | 25 | 2492 | 0.97(0.55-1.70) | 0.91 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 34 | 2633 | 16 | 2592 | 1.33(0.35-5.03) | 0.68 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 7 | 992 | 7 | 838 | 0.92 (0.32-2.66) | 0.88 |

| LVEF decline | Total | LVEF decline | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 122 | 2484 | 124 | 2492 | 0.99(0.77-1.29) | 0.96 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 160 | 2633 | 110 | 2592 | 1.48 (1.15-1.90) | 0.002 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 49 | 992 | 63 | 838 | 0.69(0.47-1.01) | 0.058 |

| Treatment discontinuation | Total | Treatment discontinuation | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 565 | 2484 | 187 | 2492 | 3.31(2.83-3.87) | <0.001 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 582 | 2633 | 384 | 2592 | 1.64(1.43-1.89) | <0.001 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 107 | 992 | 78 | 838 | 1.01(0.47-2.18) | 0.98 |

| FAEs | Total | FAEs | Total | ||||

| T+L versus T | 5 | 9 | 2484 | 9 | 2492 | 1.01(0.40-2.54) | 0.99 |

| T+L versus L | 6 | 9 | 2633 | 16 | 2592 | 0.57 (0.26-1.25) | 0.16 |

| P+T versus T | 3 | 16 | 992 | 16 | 838 | 0.92(0.46-1.86) | 0.83 |

Abbreviation: L, lapatinib; T, trastuzumab; P, pertuzumab; FAEs, fatal adverse events; CHF, congestive heart failure; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Rash

Nine trials reported rash data with 196 in dual anti-HER2 arms and 238 in anti-HER2 monotherapy arms. No significantly increased risk of severe rash was detected in the anti-HER2 combination therapy with OR 1.06 (95% CI 0.67–1.68; P=0.81) (Table 2). Sub-group analysis showed that the combination of lapatinib with trastuzumab significantly increased the risk of severe rash in comparison with trastuzumab alone (OR 4.88, 95%CI: 3.45-6.90, p<0.001), while the addition of trastuzumab to lapatinib seemed to decrease the risk of developing severe rash in comparison with lapatinib alone (OR 0.76, 95%CI:0.61-0.95, p=0.016), which suggested that the use of lapatinib was associated with an increased risk of severe rash, and clinicians should pay attention to the risk of rash during the administration of lapatinib. Additionally, the addition of pertuzumab to trastuzumab significantly increased the risk of severe rash in comparison with trastuzumab alone (OR 2.09, 95%CI: 1.27-3.44, p=0.004).

Liver toxicities

Only six trials reported liver toxicities data with 100 patients in dual anti-HER2 agent group, and 168 in control group. We did not observe a significantly increased risk of liver toxicities with dual anti-HER2 combination regimens when compared to anti-HER2 monotherapy (OR 1.16, 95%CI: 0.89-1.50, P=0.28, Table 2). Subgroup analysis showed that the addition of lapatinib to trastuzumab significantly increased the risk of liver toxicities in comparison with trastuzumab alone (OR 2.83, 95%CI: 2.00-4.00, p<0.001). Interestingly, the addition of trastuzumab to lapatinib seemed to decrease the risk of developing severe liver toxicities when compared to lapatinib alone (OR 0.74, 95%CI: 0.56-0.96, p=0.024). Based on these results, clinicians should pay attention to the risk of liver toxicities during the administration of lapatinib.

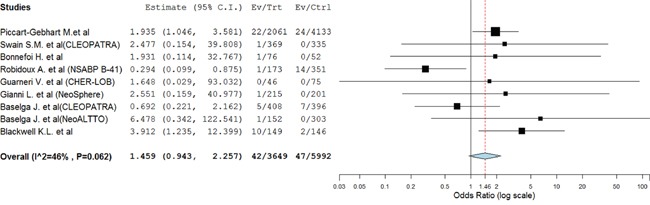

CHF and LVEF decline

There were 89 CHF events was reported, with 42 in dual anti-HER2 arms and 47 in control arms. Our results found that dual anti-HER2 agents seemed to increase the risk of CHF using a fixed effect model (OR=1.46; 95% CI 0.94–2.26; P=0.09, Figure 3). Similar results were observed in subgroup analysis based on anti-HER2 treatment (Table 3).

Figure 3. Fixed-effect Model of odds ratio (95%CI) of CHF associated with dual anti-HER2 agents versus anti-HER2 monotherapy.

A total of 9 trials reported LVEF decline data, 209 in dual anti-HER2 arms and 296 in anti-HER2 monotherapy arms. The pooled OR showed that anti-HER2 combination therapy did not increase the risk of LVEF decline (OR=1.09; 95% CI 0.90–1.31; P=0.40, Table 2). Subgroup analysis according to anti-HER2 regimen found that trastuzumab plus lapatinib combination therapy significantly increased the risk of LVEF decline in comparison with lapatinib alone (OR 1.48, 95%CI: 1.15-1.90; p=0.002, Table 3), while no significantly increased risk of LVEF decline in other dual anti-HER2 combination therapy (Table 3).

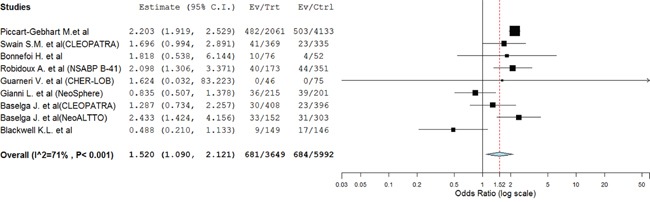

AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation

Nine trials reported treatment discontinuation data with 681 in dual anti-HER2 arms and 684 in control arms. The pooled results showed that dual anti-HER2 combination significantly increased the risk of developing treatment discontinuation yielding OR of 1.52 (95%CI: 1.09-2.12, p=0.014, Figure 4). Sub-group analysis also found that trastuzumab combined with lapatinib significantly increased the risk of treatment discontinuation in comparison with trastuzumab (OR 3.31, 95%CI: 2.83-3.87, p<0.001) or lapatinib alone (OR 1.64, 95%CI: 1.43-1.89, p<0.001, Table 3).

Figure 4. Random-effects Model of odds ratio (95%CI) of treatment discontinuation associated with dual anti-HER2 agents versus anti-HER2 monotherapy.

Fatal adverse events

A total of 289 FAEs were observed in the dual anti-HER agent group and 39 in the control group giving a pooled OR of 0.97 (95% CI 0.59–1.59; P=0.91, Table 2). In sub-group analysis, no increased risk of FAEs was observed in dual anti-HER2 combinations (Table 3).

Publication bias

We did no observed publication bias for the AEs studied excepting for severe diarrhea events by Egger tests (P= 0.022, Table 4).

Table 4. publication bias Begg and Egger test (p-value).

| Begg | Egger | |

|---|---|---|

| Rash | 0.35 | 0.18 |

| Diarrhea | 0.07 | 0.022 |

| Discontinuation treatment | 0.38 | 0.08 |

| Liver toxicities | 1.0 | 0.64 |

| LVEF decline | 0.92 | 0.71 |

| CHF | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| FAEs | 0.46 | 0.28 |

DISCUSSION

Due to the increased understanding of the molecular events involved in breast cancer development, the treatment strategy for HER2-positive breast cancer has dramatically evolved. The humanized monoclonal antibody trastuzumab has been the foundation of care for HER2 positive breast cancer in both the neoadjuvant/adjuvant and metastatic settings [24, 25]. Although the prognosis of HER2-positive breast cancer has been significantly improved by using trastuzumab, most of these patients would become resistance to trastuzumab, and new treatment strategies are clearly required. In fact, dual anti-HER2 therapy has been proven to improve clinical outcomes of early and metastatic HER2 positive breast cancer [18, 26]. However, whether dual anti-HER2 combination therapy would increase the risk of severe (grade 3 and 4) toxicities of special interest remains undetermined. In the present meta-analysis, a total of 11,941 breast cancer patients are included. Our results show that dual HER2 blockade treatment is associated with a significantly increased risk of severe diarrhea (OR 2.52, p<0.001) and treatment discontinuation (OR 1.52, p=0.014), but not for severe rash (OR 1.06, p=0.81), liver toxicities (OR 1.16, p=0.28), CHF (OR 1.46, p=0.09), LVEF decline (OR 1.09, p=0.40) and FAEs (OR 0.97, p=0.91).

Severe diarrhea could delay treatment or lead to permanent treatment discontinuation, which might reduce the efficacy of anti-HER2 treatment. The study of severe diarrhea events shows the highest RR with 2.52 with dual anti-HER2 treatment, is consistent with previously published meta-analyses [27]. Sub-group analysis also find that trastuzumab combined with lapatinib is associated with a significantly increased risk of severe diarrhea in comparison with trastuzumab or lapatinib alone, and pertuzumab combined with trastuzumab also significantly increases the risk of severe diarrhea in comparison with trastuzumab alone. As a result, clinicians should provide well-defined gastrointestinal monitoring during the administering of dual anti-HER2 therapy, and should provide immediate and effective management in case of severe diarrhea events.

We then assess the risk of treatment discontinuation related to dual anti-HER2 treatments. Our results show that dual anti-HER2 treatment is associated with a significantly increased risk of developing treatment discontinuation in comparison with anti-HER2 monotherapy. In sub-group analysis, we also find an increased risk of treatment discontinuation according to treatment regimens. All of the included trials except for Baselga et al’ study [11] reported the common adverse event for treatment discontinuation, which was hepatic toxicity, followed by diarrhea. Because AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation could reduce the efficacy of anti-HER2 treatment in breast cancer, thus clinicians should pay more attention to severe toxicities with anti-HER2 treatment.

Several previous studies have indicated a significantly increased risk of cardiac toxicities associated with anti-HER2 monotherapy trastuzumab in breast tumors [28, 29]. Wittayanukorn S et al [30] reported that trastuzumab was associated with significantly increased risk of cardiac toxicities with reporting odds ratios (ROR) as a single agent (ROR=5.74) or combination use of cyclophosphamide (ROR=16.83) or doxorubicin (ROR=17.84). Then, Valachis A et al [31] investigated the cardiac toxicities with dual HER2 blockade and did not observed an increased the risk of CHF(OR 0.58, p=0.17) and LVEF decline (OR 0.88, p=0.64) with anti-HER2 combination. In the present study, we find a tendency to increase the risk of CHF (OR=1.46; P=0.09) associated with dual anti-HER2 agents when compared to anti-HER2 monotherapy. Subgroup analysis shows that trastuzumab plus lapatinib combination therapy significantly increases the risk of LVEF decline when compared to lapatinib (OR 1.48, p=0.002), while no significantly increased risk of LVEF decline in other dual anti-HER2 combination therapy. Based on our findings, clinicians should be aware of the risk of cardiac toxicities of dual anti-HER2 treatment for the treatment of breast cancer, especially when adding trastuzumab to lapatinib.

In 2015, Abdel-Rahman O.et al performed a meta-analysis and [32] demonstrated that the use of lapatinib significantly increased the risk of skin rash in solid tumors (RR 3.04, p<0.001), but whether dual anti-her2 treatment would increase the risk of severe rash remains unknown. In our study, we does not observe a statistically significant increase of severe rash with dual anti-HER2 treatment in breast cancer patients, while sub-group analysis shows that lapatinib significantly increases the risk of severe rash which is consisted with previous research [36]. In addition, no increased risk of liver toxicities associated with the combination of anti-HER2 agents is detected. However, sub-group analysis shows that the addition of lapatinib to trastuzumab significantly increases the risk of liver toxicities in comparison with trastuzumab alone. Interestingly, the addition of trastuzumab to lapatinib seems to decrease the risk of developing severe liver toxicities when compared to lapatinib alone. Based on these results, clinicians should pay attention to liver toxicities during the administration of lapatinib. Additionally, we do not find a significantly increased risk of fatal adverse events associated with dual anti-HER2 treatment.

Several limitations need to be concerned in present study. First, our study is a study-level meta-analysis rather than an individual patient data, therefore a more comprehensive by confounding variables at the patient level could not be performed. Second, this study is a retrospective study, and the baseline characteristics of included study might be different, which might increase the heterogeneity between studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data sources

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed (up to June 2016), and Web of Science (up to June 2016) databases were searched for studies using “anti-HER2 agents”, “trastuzumab”, “pertuzumab”, “lapatinib”, “breast cancer”, “breast neoplasm”, “randomized controlled trial” and “humans”. When more than one publication was identified from the same clinical trial, we used the most recent or complete report of that trial.

To be included in the meta-analysis, a study had to satisfy the following requirements: (1) patients with pathologically confirmed breast cancer; (2) randomized controlled trials comparing anti-HER2 monotherapy (lapatinib or trastuzumab or pertuzumab) versus dual HER2 blockade treatment with or without chemotherapy regardless of treatment settings; (3) available data regarding adverse outcomes of interest (grade ≥3 AEs of diarrhea, rash, liver toxicities and congestive heart failure (CHF), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decline less than 50% or a decrease of more than 10% from baseline, AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation and fatal adverse events) and sample size.

Data extraction

Two investigators independently extracted the data according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. A third investigator reviewed all data entries. For each study, the following information was extracted: first author's name, year of publication, trial phase, number of enrolled subjects, treatment arms, number of patients in treatment and controlled groups, median age, adverse outcomes of interest [grade ≥3 AEs of diarrhea, rash, liver toxicities and congestive heart failure (CHF), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) decline, AEs lead to permanent treatment discontinuation and fatal adverse events (FAEs)], and dosage of anti-HER2 agents.

Statistical analysis

For the calculation of odds ratio (OR), patients assigned to dual anti-HER2 treatment were compared only with those assigned to anti-HER2 monotherapy in the same trial.

We used the Peto method to calculate the pooled odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), because this method provided the best CI coverage and was more powerful and relatively less biased than the fixed or random-effects analysis when dealing with low event rates. All statistical analyses were performed by using Open Meta-Analyst software version 4.16.12 (Tufts University) and Version 2 of the Comprehensive MetaAnalysis program (Biostat, Englewood, NJ).

To avoid loss of information or choices related to results from trials with multiple intervention arms (for example, three-arms trials with two anti-HER2 monotherapy arms and one combined anti-HER2 therapy arm), we merged the two relevant (anti-HER2 monotherapy) arms into one group by adding the sample sizes and numbers of people with events and we compared the merged group with the different (combined anti-HER2 therapy) arm.

Between-study heterogeneity was estimated using the χ2-based Q statistic [33]. Heterogeneity was considered statistically significant when P heterogeneity < 0.05 or I2 > 50%. Potential publication biases were evaluated for severe AEs using Begg's and Egger's tests [34, 35]. A two-tailed P value of <0.05 without adjustment for multiplicity was considered statistically significant. The results of the meta-analysis were reported as classic forest plots. The Jadad scale was used to assess the quality of included trials based on the reporting of the studies’ methods and results [36].

CONCLUSION

In comparison with anti-HER2 monotherapy, dual anti-HER2 blockade treatment is associated with an increased risk of developing severe diarrhea and treatment discontinuation. These are no evidence of an increased risk of fatal adverse events with dual-HER2 blockade treatment. In the appropriate clinical practice, dual HER2 blockade treatment remains justified due to its potential survival benefits.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interests.

FUNDING

This work is founded by the research grant (2013GS500101-05) from huimin program of the National Science and Technology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, Levin WJ, Ullrich A, McGuire WL. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235:177–182. doi: 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hynes NE. Amplification and overexpression of the erbB-2 gene in human tumors: its involvement in tumor development, significance as a prognostic factor, and potential as a target for cancer therapy. Seminars in cancer biology. 1993;4:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross JS, Slodkowska EA, Symmans WF, Pusztai L, Ravdin PM, Hortobagyi GN. The HER-2 receptor and breast cancer: ten years of targeted anti-HER-2 therapy and personalized medicine. Oncologist. 2009;14:320–368. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spector NL, Blackwell KL. Understanding the mechanisms behind trastuzumab therapy for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5838–5847. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez RH, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN. Emerging targeted therapies for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3366–3379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burstein HJ, Keshaviah A, Baron AD, Hart RD, Lambert-Falls R, Marcom PK, Gelman R, Winer EP. Trastuzumab plus vinorelbine or taxane chemotherapy for HER2-overexpressing metastatic breast cancer: the trastuzumab and vinorelbine or taxane study. Cancer. 2007;110:965–972. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith I, Procter M, Gelber RD, Guillaume S, Feyereislova A, Dowsett M, Goldhirsch A, Untch M, Mariani G, Baselga J, Kaufmann M, Cameron D, Bell R, et al. 2-year follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:29–36. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60028-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geyer CE, Forster J, Lindquist D, Chan S, Romieu CG, Pienkowski T, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Crown J, Chan A, Kaufman B, Skarlos D, Campone M, Davidson N, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2733–2743. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zardavas D, Bozovic-Spasojevic I, de Azambuja E. Dual human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 blockade: another step forward in treating patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:612–622. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328358a29a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, Im SA, Hegg R, Im YH, Roman L, Pedrini JL, Pienkowski T, Knott A, Clark E, Benyunes MC, Ross G, et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:109–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnefoi H, Jacot W, Saghatchian M, Moldovan C, Venat-Bouvet L, Zaman K, Matos E, Petit T, Bodmer A, Quenel-Tueux N, Chakiba C, Vuylsteke P, Jerusalem G, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment with docetaxel plus lapatinib, trastuzumab, or both followed by an anthracycline-based chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer: results of the randomised phase II EORTC 10054 study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:325–332. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks M, Macrae ER, Abdel-Rasoul M, Layman R, Friedman S, Querry J, Lustberg M, Ramaswamy B, Mrozek E, Shapiro C, Wesolowski R. Neoadjuvant dual HER2-targeted therapy with lapatinib and trastuzumab improves pathologic complete response in patients with early stage HER2-positive breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized prospective clinical trials. Oncologist. 2015;20:337–343. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piccart-Gebhart M, Holmes E, Baselga J, de Azambuja E, Dueck AC, Viale G, Zujewski JA, Goldhirsch A, Armour A, Pritchard KI, McCullough AE, Dolci S, McFadden E, et al. Adjuvant Lapatinib and Trastuzumab for Early Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer: Results From the Randomized Phase III Adjuvant Lapatinib and/or Trastuzumab Treatment Optimization Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1034–1042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim SB, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, Ciruelos E, Ferrero JM, Schneeweiss A, Heeson S, Clark E, Ross G, Benyunes MC, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:724–734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1413513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Azambuja E, Holmes AP, Piccart-Gebhart M, Holmes E, Di Cosimo S, Swaby RF, Untch M, Jackisch C, Lang I, Smith I, Boyle F, Xu B, Barrios CH, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): survival outcomes of a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial and their association with pathological complete response. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swain SM, Kim SB, Cortes J, Ro J, Semiglazov V, Campone M, Ciruelos E, Ferrero JM, Schneeweiss A, Knott A, Clark E, Ross G, Benyunes MC, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA study): overall survival results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:461–471. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70130-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robidoux A, Tang G, Rastogi P, Geyer CE, Jr, Azar CA, Atkins JN, Fehrenbacher L, Bear HD, Baez-Diaz L, Sarwar S, Margolese RG, Farrar WB, Brufsky AM, et al. Lapatinib as a component of neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive operable breast cancer (NSABP protocol B-41): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1183–1192. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70411-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guarneri V, Frassoldati A, Bottini A, Cagossi K, Bisagni G, Sarti S, Ravaioli A, Cavanna L, Giardina G, Musolino A, Untch M, Orlando L, Artioli F, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy plus trastuzumab, lapatinib, or both in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive operable breast cancer: results of the randomized phase II CHER-LOB study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1989–1995. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.0823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, Roman L, Tseng LM, Liu MC, Lluch A, Staroslawska E, de la Haba-Rodriguez J, Im SA, Pedrini JL, Poirier B, Morandi P, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo HS, Sledge G, Aktan G, Ellis C, Florance A, Vukelja S, Bischoff J, Baselga J, O'Shaughnessy J. Overall survival benefit with lapatinib in combination with trastuzumab for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive metastatic breast cancer: final results from the EGF104900 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2585–2592. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baselga J, Bradbury I, Eidtmann H, Di Cosimo S, de Azambuja E, Aura C, Gomez H, Dinh P, Fauria K, Van Dooren V, Aktan G, Goldhirsch A, Chang TW, et al. Lapatinib with trastuzumab for HER2-positive early breast cancer (NeoALTTO): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;379:633–640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blackwell KL, Burstein HJ, Storniolo AM, Rugo H, Sledge G, Koehler M, Ellis C, Casey M, Vukelja S, Bischoff J, Baselga J, O'Shaughnessy J. Randomized study of Lapatinib alone or in combination with trastuzumab in women with ErbB2-positive, trastuzumab-refractory metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1124–1130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimawi MF, Mayer IA, Forero A, Nanda R, Goetz MP, Rodriguez AA, Pavlick AC, Wang T, Hilsenbeck SG, Gutierrez C, Schiff R, Osborne CK, Chang JC. Multicenter phase II study of neoadjuvant lapatinib and trastuzumab with hormonal therapy and without chemotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-overexpressing breast cancer: TBCRC 006. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1726–1731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.8027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurvitz SA, Hu Y, O'Brien N, Finn RS. Current approaches and future directions in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahn ER, Vogel CL. Dual HER2-targeted approaches in HER2-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:371–383. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1781-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Fu W, Gao X, Xu Q, Wu H, Tan W. Risk of severe diarrhea with dual anti-HER2 therapies: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:4077–4085. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1533-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herbst RS, Sun Y, Eberhardt WE, Germonpre P, Saijo N, Zhou C, Wang J, Li L, Kabbinavar F, Ichinose Y, Qin S, Zhang L, Biesma B, et al. Vandetanib plus docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (ZODIAC): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:619–626. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70132-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leboulleux S, Bastholt L, Krause T, de la Fouchardiere C, Tennvall J, Awada A, Gomez JM, Bonichon F, Leenhardt L, Soufflet C, Licour M, Schlumberger MJ. Vandetanib in locally advanced or metastatic differentiated thyroid cancer: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:897–905. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70335-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittayanukorn S, Qian J, Johnson BS, Hansen RA. Cardiotoxicity in targeted therapy for breast cancer: A study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1078155215621150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valachis A, Nearchou A, Polyzos NP, Lind P. Cardiac toxicity in breast cancer patients treated with dual HER2 blockade. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2245–2252. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Rahman O, Fouad M. Risk of mucocutaneous toxicities in patients with solid tumors treated with lapatinib: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:975–986. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1020367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zintzaras E, Ioannidis JP. Heterogeneity testing in meta-analysis of genome searches. Genetic epidemiology. 2005;28:123–137. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusuf S, Peto R, Lewis J, Collins R, Sleight P. Beta blockade during and after myocardial infarction: an overview of the randomized trials. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1985;27:335–371. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(85)80003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Furuse K, Kawahara M, Hasegawa K, Kudoh S, Takada M, Sugiura T, Ichinose Y, Fukuoka M, Ohashi Y, Niitani H. Early phase II study of S-1, a new oral fluoropyrimidine, for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6:236–241. doi: 10.1007/pl00012111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Pham B, Jones A, Cook DJ, Jadad AR, Moher M, Tugwell P, Klassen TP. Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 1998;352:609–613. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01085-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]