Abstract

Background

Conflicting evidence exists regarding the effects of platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and lymphocyte/monocyte ratio(LMR) on the prognosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. This study aimed to evaluate the roles of the PLR and LMR in predicting the prognosis of CRC patients via meta-analysis.

Methods

Eligible studies were retrieved from the PubMed, Embase,andChina National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases, supplemented by a manual search of references from retrieved articles. Pooled hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the generic inverse variance and random-effect model to evaluate the association of PLR and LMR with prognostic variables in CRC, including overall survival (OS), cancer-specific survival (CSS) and disease-free survival (DFS).

Results

Thirty-three studies containing 15,404 patients met criteria for inclusion. Pooled analysis suggested that elevated PLR was associated with poorer OS (pooled HR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.41 – 1.75, p< 0.00001, I2=26%) and DFS (pooled HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.31 – 1.92, p< 0.00001, I2=66%). Conversely, high LMR correlated with more favorable OS (pooled HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.50 – 0.68, p< 0.00001, I2=44%), CSS (pooled HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40 – 0.72, p< 0.00001, I2=11%) and DFS (pooled HR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.71– 0.94,p=0.005, I2=29%).

Conclusions

Elevated PLR was associated with poor prognosis, while high LMR correlated with more favorable outcomes in CRC patients. Pretreatment PLR and LMR could serve as prognostic predictors in CRC patients.

Keywords: platelet/lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte/monocyte ratio, colorectal cancer, prognostic predictor, inflammatory markers

INTRODUCTION

CRC represents the third most common cause of cancer-related death in men and women in the united states [1]. It is estimated that 134,490 new cases will be diagnosed and 49,190 deaths will occur in 2016 [1]. Despite advances in surveillance, diagnosis and treatment of CRC, a large number of the patients are still diagnosed at an advanced stage and thus the therapeutic options are limited, resulting in a 5-year survival rate of only about 65% much lower than expected [2]. The discovery of prognostic factors is of clinical importance to guide therapeutic options and surveillance strategies. However, the prognoses of CRC patients with similar clinicopathologic characteristics vary widely due to high heterogeneity in tumor biology [3]. Currently, the discovery of prognostic biomarkers mainly depends on surgical specimens, which may not be representative of the veritable burden of CRC [4]. In addition, as many prognostic factors are evaluated postoperatively, there are still pending circulating biomarkers of early predicting clinical outcome.

Recently, there has been intense interest in the prognostic value of peripheral blood biomarkers in CRC. Inflammation has been reported to be involved in carcinogenesis and disease progression [5] and local cancer-related inflammation can be reflected by a systemic inflammatory response (SIR). Nearly a third of cancer patients have thrombocytosis at diagnosis and aberrant activation of platelets has been shown to be associated with CRC [6, 7]. Lymphocytes are essential components of the tumor microenvironment, which contributes to carcinogenesis [8]. Monocytes have been reported to influence CRC progression and can be used to predict prognosis [9, 10]. PLR and LMR, two representative indices of SIR, have been found to impact survival in a variety of solid malignancies [11–14], including CRC [15, 16]. As the collection of circulating inflammatory markers, including PLR and LMR, is simple, noninvasive, and easily accessible. Circulating levels of inflammatory markers have been investigated as applicable and cost-effective prognostic predictors in cancer patients [17]. Although the underlying mechanisms of altered PLR and LMR in CRC development remains unknown, numerous studies have investigated their value as prognostic factors and markers for predicting response to therapy. However, the results of these studies are conflicting [16, 18, 19]. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of the literature is warranted.

In the present study, this meta-analysis represents the most comprehensive and up-to-date review on the prognostic value of PLR and LMR in CRC. The results of this study showed that elevated PLR and LMR were associated with poor and favorable prognosis in CRC, respectively, suggesting that these two factors might be used as prognostic factors in CRC patients and applied in surveillance programs.

RESULTS

Search results

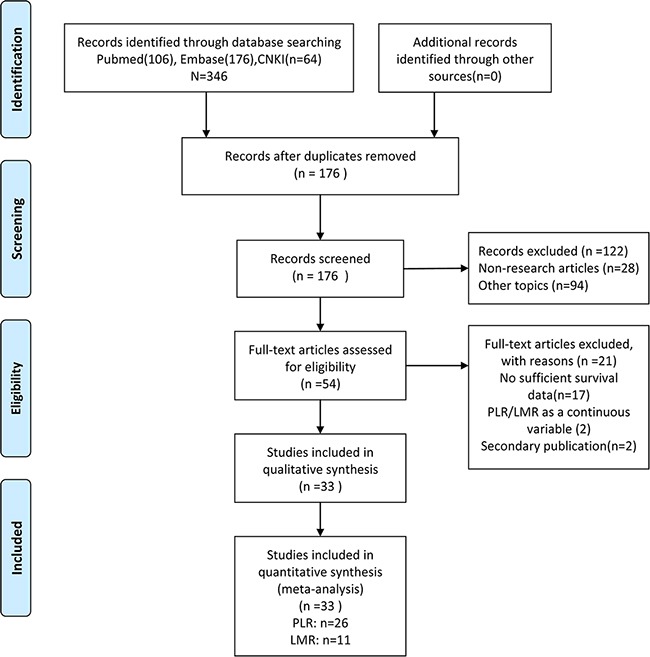

Cohen's kappa for inter-reviewer agreement was 0.80 (95% CI=0.69 to 0.93). The literature search process is summarized in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). Initial assessment of titles and abstracts identified 346 potentially relevant publications which included 170 duplicates, 94 irrelevant studies, and 28 non-research articles. After further screening of full-texts of the remaining 54 articles, 21 papers were excluded due to insufficient survival data or for being a secondary publication. Altogether, 33 studies [3, 16, 18–48] were finally selected for inclusion. Among these studies, 22 investigated PLR, 8 studied LMR and 3 evaluated both PLR and LMR.

Figure 1. Flow- diagram shows the selection of literature for meta-analysis.

Study description

The basic features of the 33 studies are summarized in Table 1. In total, 15,404 patients were included. All included studies were retrospective cohorts. Among these studies, 2 were published in 2012, 4 in 2013, and the remaining 27 (82%) were published in 2014 or later. Sample sizes ranged from 57 to 5336 patients. The mean or median age of subjects ranged from 49 to 71.3 years. The mean or median follow-up duration ranged from 10.4 to 68 months. Patients in 23 studies [3, 16, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29–37, 40–44, 46–48] were Asian, while subjects were Caucasian in the other 10 studies [18–22, 25, 28, 38, 39, 45]. 6 studies [16, 41–44] included all CRC stages; 16 studies [3, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 34, 37, 40, 45, 48] only included non-metastatic CRC; 10 studies [19, 22, 26, 29, 35, 36, 38, 39, 45–47] only included metastatic CRC; and 1 study [45] included two cohorts evaluating the outcomes of both non-metastatic and metastatic CRC. Twenty three studies analyzed PLR as a single dichotomous cut-off (group 1), while three studies [3, 38, 48] defining three risk categories with two cut-offs reported a single HR of PLR (group 2). All studies evaluated LMR as a dichotomous cut-off.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis.

| Study Published year |

Country Duration |

Sample size Median age |

Main treatment Tumor site |

Study design Clinical stage |

Outcome indices Survival analysis |

Follow-up (median and range) |

Cut-off value |

determine the cut-off value |

inflammatory disorders | Study quality# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baranyai et al. 2013 | USA 2001-2011 |

336 CRC:67 |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS MVA |

67 | PLR:300 | RPS | No | 6 |

| Baranyai et al. 1 2013 | USA 2001-2011 |

118 mCRC:61* |

mCRC | Retrospective M |

OS MVA |

NR | PLR:300 | RPS | No | 6 |

| Carruthers et al. 2012 |

UK 2000-2005 |

115 63.8(32.3–81.1)* |

NeoCRT/adjCT +CSR RC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS UVA |

37.1 | PLR:160 | RPS | NR | 6 |

| Chan et al. 2016 |

Australia 1998-2012 |

1623 NR |

CRT +CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS PLR:UVA;LMR:MUV |

52(27-92) | PLR:258 LMR:2.38 |

MaxStat analysis | NR | 7 |

| Choi et al. 2015 |

Canada 2004-2012 |

549 68.7(68.3-98.6) |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS,RFS/DFS UVA |

48(0-124.8) | PLR:295 | MaxStat analysis | NR | 8 |

| Chen et al. 2015 |

China 2010-2014 |

205 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

RFS/DFS MVA |

NR | PLR:176 | ROC analysis | NR | 6 |

| Cui et al. 2015 |

China 2007-2011 |

822 NR |

CSR±adjCT/CRT CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS,RFS/DFS MVA |

NR | PLR:194 | ROC analysis | NO | 7 |

| Duan et al. 2014 |

China 2007-2008 |

57 71.3* |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective NM |

OS MVA |

NR | PLR:250 | NR | NR | 5 |

| Kwon et al. 2012 |

South Korea 2005-2008 |

200 64(26–83) |

CSR±adjCT/CRT CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS MVA |

33.6 | PLR:<150 / 150-300 / >300 | NR | NR | 8 |

| Li et al. 2016 |

China 2007-2014 |

5,336 59(51–66) |

CSR±adjCT CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS MVA |

55.2 | PLR:219 LMR:2.83 |

X-tile software | NO | 9 |

| Li et al. 2015 |

China 2003-2012 |

110 62.9* |

PSR+CT CC |

Retrospective M |

OS MVA |

10.4(0.9-122.2) | PLR:162 | NR | NR | 7 |

| Lin et al. 2016 |

China 2005-2013 |

488 54(37-72) |

CT CRC |

Retrospective M |

OS MVA |

23.5(4.3–32.8) | LMR:3.11 | ROC | NO | 9 |

| Liu et al. 2013 |

China 2005-2011 |

140 54.1* |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective NM |

OS MVA |

NR | PLR:250 | NR | NR | 6 |

| Luo et al. 2014 |

China 2006-2010 |

162 NR |

NR CRC |

Retrospective NM |

OS MVA |

NR | PLR:250 | NR | NR | 5 |

| Mori et al. 2015 |

Japan 2007-2011 |

157 67(35-89) |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

DFS UVA |

20.5(0.2–62.4) | PLR:150 | RPS | NO | 7 |

| Neal et al. 2015 |

UK 2006-2010 |

302 64.8*(26-85) |

CSR±CT CRLM |

Retrospective M |

OS,CSS UVA |

29.7(4-96) | PLR:<150 / 150-300 / >300 LMR:2.35 |

PLR:RPC LMR:ROC |

NO | 8 |

| Neofytou et al. 2014 |

UK 2005-2012 |

140 NR |

NeoCT/adjCT +CSR CRLM |

Retrospective M |

OS,DFS MVA |

33(1-103) | PLR:150 | ROC analysis | NO | 9 |

| Neofytou et al. 2015 |

UK 2005-2012 |

140 NR |

NeoCT/adjCT +CSR CRLM |

Retrospective M |

OS,CSS MVA DFS UVA |

33(1-103) | LMR:3 | ROC analysis | NO | 9 |

| Ni et al. 2016 |

China 2010-2015 |

148 60.2*(20-74) |

CT CRC |

Retrospective M |

OS MVA |

12(0.2-67) | PLR:174 | RPS | NO | 8 |

| Ozawa et al. 2015 |

Japan 2000-2010 |

234 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

DFS,CSS MVA |

64(1-173) | PLR:25.4 | ROC analysis | NO | 9 |

| Ozawa et al. 1 2015 |

Japan 1997-2012 |

117 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective M |

DFS,CSS MVA |

39(4-170) | LMR:3 | ROC analysis | NO | 9 |

| Passardi et al. 2016 |

Italy NR |

289 NR |

CT CRC |

Prospective M |

OS,PFS MVA |

NR | PLR:169 | X-tile software | NR | 8 |

| Shibutani et al. 2015 |

Japan 2005-2010 |

104 64(27-86) |

CT CRC |

Retrospective M |

OS MVA |

22.4(2.6-69.5) | LMR:3.38 | ROC analysis | NR | 6 |

| Son et al. 2013 |

South Korea 2005-2007 |

624 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS MVA |

42(1-66) | PLR:300 | NR | NR | 7 |

| Song et al. 2015 |

South Korea 2006-2003 |

177 52(25-81) |

RVS CRC |

Retrospective M |

OS UVA |

3.1(0.1-33.3) | LMR:3.4 | ROC analysis | NR | 7 |

| Stotz et al. 2014 |

Austria 1996-2011 |

372 64(27-95) |

CSR CR |

Retrospective N |

OS MVA |

68(1-190) | LMR:2.14 | ROC analysis | NR | 8 |

| Sun et al. 2014 |

China 2005-2008 |

255 59.47* |

CSR CC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS MVA |

NR | PLR:<150 / 150-300 / >300 | NR | NR | 7 |

| Szkandera et al. 2014 |

Austria 1996-2011 |

372 64(27-95) |

CSR CC |

Retrospective N |

OS MVA |

68(1-190) | PLR:225 | ROC analysis | NR | 8 |

| Toiyama et al. 2013 |

Japan 2001-2012 |

84 64.5(33-80) |

CRT+CSR RC |

Retrospective N |

OS,DFS UVA |

56(2-147) | PLR:150 | RPS | NR | 7 |

| Xiao et al. 2015 |

China 2004-2011 |

280 NR |

CSR RC |

Retrospective N |

DFS MVA |

52(0.5-106.37) | LMR:3.78 | median value | NR | 7 |

| Ying et al. 2014 |

China 2005-2010 |

205 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective N |

RFS,OS,CSS MVA |

NR | PLR:176 | ROC analysis | NO | 7 |

| You et al. 2016 |

China 2005-2011 |

1314 66* |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective NM |

DFS,OS MVA |

56.9 | PLR:150 | RPS | No | 8 |

| Yu et al. 2016 |

China 2011-2014 |

125 49(18-72) |

CT CRC |

Retrospective M |

PFS,OS MVA |

NR | LMR:3.6 | ROC analysis | NO | 6 |

| Zou et al. 2016 |

China 2006-2012 |

216 NR |

CSR CRC |

Retrospective NM |

OS MVA |

38(3′85 ) | PLR: 246.36 | ROC analysis | No | 8 |

Notes: Tumor site : CRC colorectal cancer, mCRC metastatic colorectal cancer, CC colon cancer, RC rectal cancer, CRLM colorectal liver metastases. Treatment: CSR curative surgical resection, PSR palliative surgical resection, CRT chemoradiotherapy, CT chemotherapy, neoCRT neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, adjCT adjuvant chemotherapy, RVS Rhus verniciflua stokes. Study design: prospective, retrospective Clinical stage: N nonmetastatic, M metastatic, NM nonmetastatic and metastatic.Outcome indices: OS overall survival, DFS disease-free survival, CSS cancer specific survival, PFS progression-free survival, RFS recurrence-free survival.Survival analysis: MVA multivariate analysis, UVA univariate analysis. Determine the cut-off value: RPS refer to the previous study, NR not reported, ROC receiver operating curve analysis, X-tile 3.6.1 software R package MaxStat #Study quality was determined based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (range, 1–9) *Mean

Impact of PLR on OS and DFS in CRC Patients

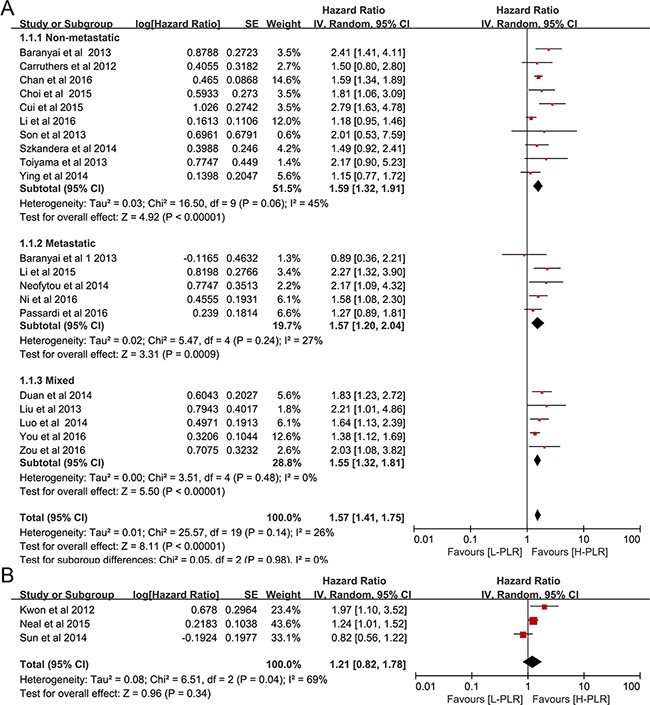

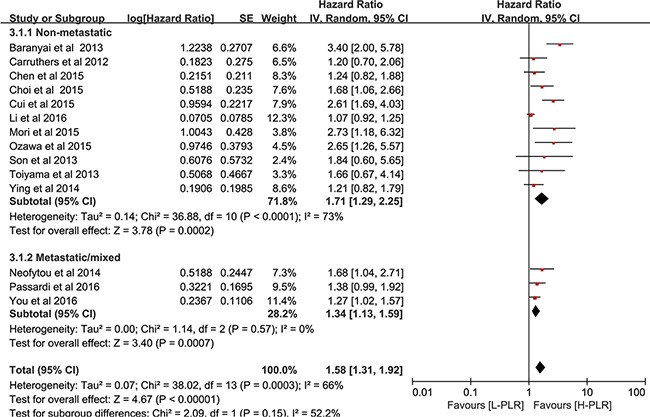

Twenty studies [16, 18–21, 23, 24, 28, 29, 31, 32, 37, 39–45] in group1, which included 12,760 CRC patients, reported an association between PLR and OS. As seen in Figure 2, the analysis of pooled data showed that elevated PLR was correlated with poor OS in group1 (pooled HR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.41-1.75, p< 0.00001, I2=26%, Figure 2A). Furthermore, the results of subgroup indicated that increased PLR was a marker for poor prognosis in non-metastatic CRC (pooled HR = 1.59, 95% CI: 1.32 – 1.91, p< 0.00001, Figure 2A), metastatic CRC (pooled HR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.20 – 2.04, p< 0.00001, Figure 2A) and patients at all stages (pooled HR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.32 – 1.81, p< 0.00001, Figure 2A). For studies in group 2 (two cut-offs, usually <150, 150–300, >300), the pooled HR for OS per risk category was 1.21 (95% CI, 0.82–1.78, p = 0.10, Figure 2B). Fourteen studies [16, 19, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 37, 39, 40, 45] comprising 10,410 CRC patients investigated the association between PLR and DFS. As shown in Figure 3, patients with high pretreatment PLR had significantly shorter DFS (pooled HR = 1.58, 95% CI: 1.31 – 1.92, p< 0.00001, I2=66%), suggesting that elevated PLR was associated with poor DFS.

Figure 2. Forest plot reflects the association between PLR and OS.

A. group 1, a single cutoff for PLR. B. group 2, two cutoffs for PLR.

Figure 3. Forest plot reflects the association between PLR and DFS.

Impact of LMR on OS,CSS and DFS in CRC Patients

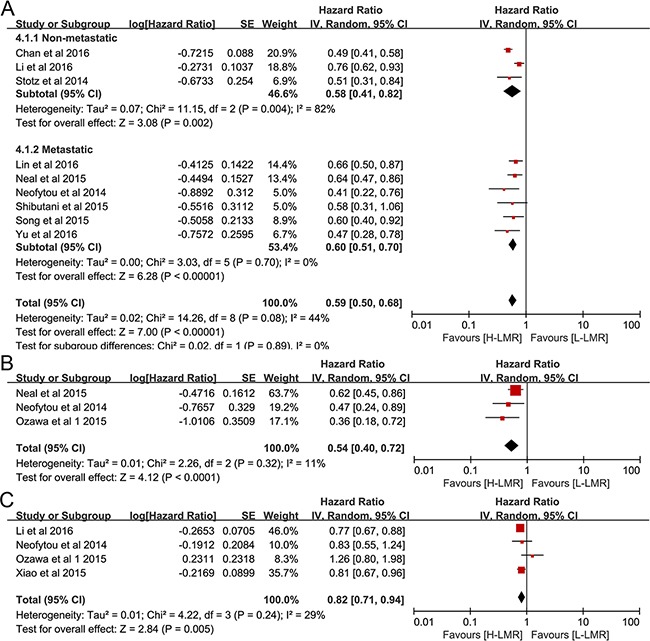

Nine studies [18, 20, 25, 26, 31, 35, 38, 39, 47] which included a total of 8667 CRC patients provided data for OS. As depicted in Figure 4, pooled data showed that elevated LMR was correlated with favorable OS in CRC patients(pooled HR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.50 – 0.68, p< 0.00001, I2=44%, Figure 4A). Subgroup statistics indicated that this prognostic role of LMR was observed in both metastatic or non-metastatic CRC patients (pooled HR = 0.60, 95% CI = 0.51 – 0.70, p< 0.001 and pooled HR =0.58, 95% CI = 0.41 – 0.82, p=0.002, respectively, Figure 4A). The pooled statistics of three studies [36, 38, 39], which studied the correlation between LMR and CSS, suggested that elevated LMR was a prognostic factor for favorable CSS (pooled HR = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.40 – 0.72, p< 0.00001, I2=11%, Figure 4B). Our results also revealed that LMR was a predictor for prolonged DFS (pooled HR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.71 – 0.94, p=0.005, I2=29%, Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Forest plot reflects the association between LMR and OS.

A. CSS B. DFS C.

Subgroup analysis

Exploratory subgroup analyses were conducted according to geographic region (Asia and non-Asia), sample size (large and small), disease stage (metastatic/mixed and non-metastatic disease), methods for survival analysis(multivariable and univariate analysis), cut-off (≥185 and <185) and methods for determining cut-off (ROC/software analysis and referring to the previous study). However, results of the subgroup analysis for these variables did not alter the prognostic roles of PLR on OS and DFS and LMR on OS. While LMR was not associated with DFS in the non-Asian, small sample size, metastatic/mixed, univariate analysis and cut-off value≥3.0 subgroups. The difference is more likely clinically insignificant in these subgroups considering only four studies were used for this portion of the analyses. The details of the subgroup analyses are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Subgroup analyses for OS and DFS/RFS.

| OS | I2 | DFS/RFS | I2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | HR (95%CI, P value) | N | HR (95%CI, P value) | ||||

| PLR | Overall | 20 | 1.57 (1.41-1.75, p<0.00001) | 26% | 14 | 1.58 (1.31-1.92, p<0.00001 ) | 66% |

| Geographic region | |||||||

| Asia | 12 | 1.60 (1.36-1.88, p<0.00001) | 40% | 9 | 1.50(1.19-1.90, p=0.0007) | 68% | |

| Non-Asia | 8 | 1.58 (1.39-1.80, p<0.00001) | 0% | 5 | 1.71 (1.24-2.35, p=0.001 ) | 58% | |

| Sample size | |||||||

| Large (n >200) | 10 | 1.56 (1.31-1.86, p<0.00001 ) | 49% | 9 | 1.66 (1.26-2.20, p=0.0004) | 76% | |

| Small (n <200) | 10 | 1.64 (1.44-1.87, p<0.00001) | 0% | 5 | 1.38 (1.14-1.68, p=0.0009) | 5% | |

| Cut-off value | |||||||

| ≥185* | 12 | 1.66 (1.42-1.95, p<0.00001) | 38% | 5 | 1.93 (1.14-3.26, p=0.01) | 87% | |

| <185 | 8 | 1.45 (1.26-1.66, p<0.00001) | 0% | 9 | 1.37 (1.19-1.56, p<0.00001) | 0% | |

| Methods to determine cut-off | |||||||

| ROC/software analysis | 8 | 1.53 (1.26-1.86, p<0.00001 ) | 54% | 8 | 1.51 (1.19-1.91, p=0.0007) | 68% | |

| RPS or NR | 12 | 1.60 (1.41-1.81, p<0.00001) | 0% | 6 | 1.80 (1.20-2.69, p=0.005) | 65% | |

| Disease stage | |||||||

| Non-metastatic | 10 | 1.59 (1.32-1.91, p<0.00001) | 45% | 11 | 1.71 (1.29-2.25, p=0.0002) | 73% | |

| Metastatic/mixed | 10 | 1.54 (1.36-1.75, p<0.00001) | 0% | 3 | 1.34 (1.13-1.59, p=0.0007 ) | 0.06 | |

| Variable type | |||||||

| Multivariable | 16 | 1.58 (1.37-1.81, p<0.00001 ) | 38% | 10 | 1.58 (1.26-1.98, p<0.00001) | 73% | |

| Univariable | 4 | 1.62 (1.39-1.89, p<0.00001) | 0% | 4 | 1.61 (1.18-2.18, p=0.002) | 0% | |

| LMR | Overall | 9 | 0.59 (0.50-0.68, p<0.00001) | 44% | 4 | 0.82 (0.71-0.94, p=0.005) | 29% |

| Geographic region | |||||||

| Asia | 6 | 0.66 (0.58-0.76, p<0.00001) | 0% | 3 | 0.83 (0.70-0.99, p=0.04) | 52% | |

| Non-Asia | 3 | 0.52 (0.42-0.64, p<0.00001) | 32% | 1 | 0.83 (0.55-1.24, p=0.36) | NA | |

| Sample size | |||||||

| Large (n >200) | 5 | 0.61 (0.50-0.75, p<0.00001) | 67% | 2 | 0.78 (0.70-0.81, p<0.00001) | 0% | |

| Small (n <200) | 4 | 0.52 (0.40-0.68, p<0.00001) | 0% | 2 | 1.01 (0.67-1.52, p=0.97) | 46% | |

| Cut-off value | |||||||

| ≥3.00 | 5 | 0.58 (0.48-0.71, p<0.00001 ) | 0% | 3 | 0.89 (0.70-1.13, p=0.33) | 39% | |

| <3.00 | 4 | 0.61 (0.50-0.75, p<0.00001) | 67% | 1 | 0.77 (0.76-0.88, p=0.0002) | NA | |

| Disease stage | |||||||

| Non-metastatic | 3 | 0.58 (0.41-0.82, p=0.002) | 82% | 2 | 0.78 (0.70-0.81, p<0.00001) | 0% | |

| Metastatic/mixed | 6 | 0.60 (0.51-0.70, p<0.00001) | 0% | 2 | 1.01 (0.67-1.52, p=0.97) | 46% | |

| Variable type | |||||||

| Multivariable | 8 | 0.58 (0.48-0.68, p<0.00001) | 49% | 3 | 0.83 (0.70-0.99, p=0.04) | 52% | |

| Univariable | 1 | 0.64 (0.47-0.86, p=0.003) | NA | 1 | 0.83 (0.55-1.24, p=0.36) | NA | |

*median

Sensitivity analysis

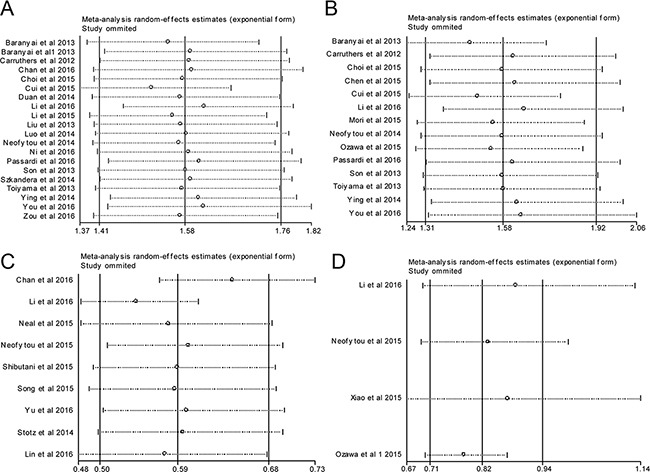

Sensitivity analysis was performed by assessing the potential impact of individual studies on the pooled data. As illustrated in Figure 5, pooled HR was not significantly altered when each single study was withdrawn every time. Notably, there was substantial heterogeneity regarding the impact of LMR on DFS (I2=66%); however, exclusion of three studies [31, 37, 45] reduced the I2 to 0% and did not change the prognostic significance ( pooled HR =1.39, 95% CI=1.23–1.58, p <0.001).

Figure 5. Sensitivity analysis for meta-analysis.

A. correlation of PLR with OS; B. correlation of PLR with DFS; C. correlation of LMR with OS; D. correlation of LMR with DFS.

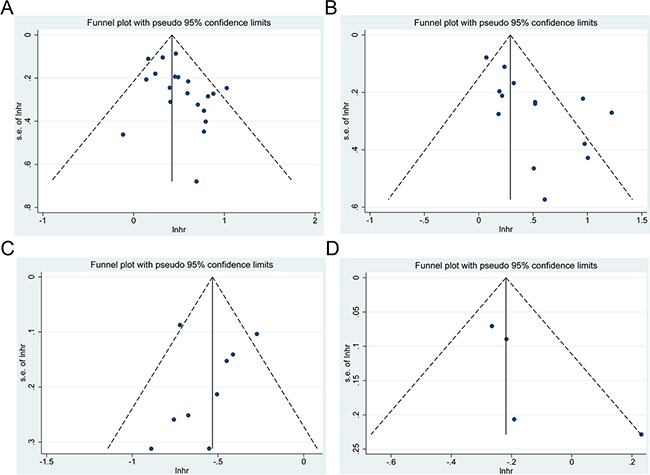

Publication bias

As shown in Figure 6, the funnel plots showed evidence for symmetry in studies of the impact of LMR on CRC survival, but not in studies of PLR, suggesting that a publication bias about for the effect of PLR on CRC outcomes may exist. Therefore, the Begg's and Egger's tests were conducted to assess the bias more precisely. Studies concerning PLR and pooled OS (Egger's test, p=0.048; Begg's test, p=0.127) and DFS (Egger's test, p=0.004; Begg's test, p=0.063) showed publication bias (Supplementary Table 1). After doing a trim fill analysis, we found that the pooled HR was 1.453 (95% CI = 1.286 −1.641, p <0.001) for OS and 1.206 (95% CI = 0.982 −1.482, p=0.074) for DFS, suggesting that a publication bias appeared to overestimate DFS.

Figure 6. Funnel plot for publication bias.

A. correlation of PLR with OS; B. correlation of PLR with DFS; C. correlation of LMR with OS; D. correlation of LMR with DFS.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies [49–51] have shown correlation between the SIR and clinical outcomes in various cancers; However, conflicting evidence exists regarding the effects of PLR and LMR on the prognosis of CRC patients. In this meta-analysis of 33 studies which includes 15,404 cases, we reevaluated the prognostic roles of the PLR and LMR in CRC. The results of this study suggested that pretreatment PLR and LMR could be used as prognostic predictors in CRC patients. Elevated PLR was associated with poor OS and reduced DFS. On the contrary, high LMR was correlated with favorable OS, CSS and DFS. Analyses stratified by geographic region, sample size, different cut-off (≥185 and <185) and methods in determining cut-off did not alter the effects of PLR and LMR on OS and DFS.

Most of included studies (82%) were published in 2014 or later, highlighting the recent interest in investigating the prognostic values of PLR and LMR in CRC. To our knowledge, the meta-analysis is a more comprehensive update that systematically and quantitatively evaluates this topic. When assessing the impact of PLR on OS, the pooled HR of three studies which defined three risk categories (binary cut-offs) did not achieve statistical significance. This may be due to numerically lower HRs that apply per higher risk category compared with using a single cutoff [52]. We performed a sensitivity analysis, which indicated our results were robust. Publication bias was identified by a funnel plot and the Begg's and Egger's tests. The results revealed that studies concerning PLR and pooled OS and DFS showed publication bias, indicating that results, especially those regarding the impact of PLR on DFS, should be interpreted with caution.

The underlying mechanisms by which PLR and LMR influence the survival of CRC patients remains largely unknown. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the underlying biological basis. Thrombocytosis is commonly observed in cancer patients and is linked with decreased survival [53]. Platelets can release a myriad of growth factors which may facilitate cancer growth and dissemination. Orellana et al. [54] co-cultivated ovarian cancer cells with human platelets and found that platelet-cancer interactions contributed to the formation of metastatic foci. In addition, blockade of key platelet receptors attenuated ovarian cancer metastasis. Lymphocytopenia is a key component of a high PLR. Lymphocytes represent the cellular basis of cancer immunosurveillance. Compelling evidence indicates that lymphocytes induce cytotoxic cell death and inhibit tumor cell proliferation and migration, thereby dictating the host's immune response to cancer [55]. Decreased lymphocyte counts may lead to downregulation of the immune response against cancer. Monocytes may reflect the formation of tumor-associated macrophages(TAMs), which represent pivotal components of tumor microenvironment promoting progression [56]. Furthermore, PLR and LMR are representative indexes of SIR. Aberrant SIR is considered to be associated with cancer progression. In addition, systemic inflammation can decrease organ function in cancer patients; thus, poor oncologic outcomes are observed [57].

Several potential limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the major disadvantage of this study was the discordance of PLR and LMR cut-offs, which lead to inter-study heterogeneity. Second, patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy were included in many of the studies, which may alter the course of the survival. Third, significant heterogeneity was found in publications studying the impact of PLR on OS and DFS. In addition, several disease conditions, including liver diseases or inflammatory diseases, may affect PLR and/or LMR. Some eligible studies did not control for these confounding factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature search

Pubmed, Embase, and CNKI were systematically searched for literature up to June 2016. The main medical subject heading (Mesh) terms and text words included colorectal cancer, lymphocyte, platelets, monocytes and prognosis. The search strategies were summarized in Supplementary Appendix. The languages of articles were limited to English and Chinese. The bibliographies of relevant articles were also searched manually for additional eligible studies. Inter-reviewer agreement was evaluated using Cohen's kappa. Any disagreements were discussed and arbitrated by a second reviewer.

Study selection

A study was considered eligible only if the publication met all of the following criteria: (a) patients were pathologically diagnosed with CRC; (b) pretreatment PLR and/or LMR and cutoff values were reported; (c) PLR and/or LMR were used as prognostic indicators of OS, CSS or DFS; (c) hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were reported in text. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) PLR and/or LMR were reported as continuous variables; (b) studies had overlapping or duplicated data; (c) non-research articles or studies that were based on animal or human cell lines; (d) publications were not subjected to peer-review (dissertations or theses).

Data extraction

Two investigators independently gathered data. The following data were extracted: publication details (first author's surname, year of publication, geographic region of study), population characteristics (patients number, age, and sex), cancer and follow-up data (cancer site, stage, treatment strategy, median/mean follow-up duration, survival analysis), PLR and/or LMR data (assessment method and cut-off values), cut-off values were used to determine ‘high’ versus ‘low’ PLR and LMR.

Qualitative assessment

The quality of each of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS, Supplementary Table 2) [58], which includes 3 criteria, namely, selection (0–4 points), comparability (0–2 points) and outcomes (0–3 points). NOS scores≧6 were defined as high-quality. (Supplementary Table 3).

Statistical analysis

The HR with 95% CI was directly retrieved from each of the article. Pooled HR was calculated using the generic inverse variance and random-effect model. A combined HR >1 implied a worse prognosis in the group with elevated PLR or LMR. Inter-study heterogeneity was measured by performing the c2-based Cochran's Q test and Higgins’ I2 statistics. A P-value <0.10 and/or I2>50% indicated significant heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed with visual inspection of funnel plots and precisely evaluated by Egger's and Begg's tests. A P-value < 0.05 in the Z test for pooled HR, or no overlap of the 95% CI with 1 was considered statistically significant. This study adhered to the PRISMA guidelines and all data analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.2 (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) and Stata 12.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, pretreatment PLR and LMR could be used as prognostic predictors in CRC patients. Elevated PLR was associated with poor OS and DFS. In contrast, high LMR correlated with favorable OS, CSS and DFS. Further studies are necessary to confirm these findings and elucidate the underlying biology.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLES

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported in part by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2016JM8035).

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:252–71. doi: 10.3322/caac.21235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon HC, Kim SH, Oh SY, Lee S, Lee JH, Choi HJ, Park KJ, Roh MS, Kim SG, Kim HJ, Lee JH. Clinical significance of preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte versus platelet-lymphocyte ratio in patients with operable colorectal cancer. Biomarkers. 2012;17:216–22. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.656705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ocana A, Diez-Gonzalez L, Garcia-Olmo DC, Templeton AJ, Vera-Badillo F, Jose Escribano M, Serrano-Heras G, Corrales-Sanchez V, Seruga B, Andres-Pretel F, Pandiella A, Amir E. Circulating DNA and Survival in Solid Tumors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:399–406. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Eldar S, Lev LM. Diagnosis of cancer-associated vascular disorders. Cancer. 1996;77:1759–67. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960501)77:9<1759::aid-cncr1>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Iwasaki Y, Kubota K. Preoperative thrombocytosis is associated with survival after surgery for colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:887–91. doi: 10.1002/jso.23163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffmann TK, Dworacki G, Tsukihiro T, Meidenbauer N, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. Spontaneous apoptosis of circulating T lymphocytes in patients with head and neck cancer and its clinical importance. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2553–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamm A, Prenen H, Van Delm W, Di Matteo M, Wenes M, Delamarre E, Schmidt T, Weitz J, Sarmiento R, Dezi A, Gasparini G, Rothe F, Schmitz R, et al. Tumour-educated circulating monocytes are powerful candidate biomarkers for diagnosis and disease follow-up of colorectal cancer. Gut. 2016;65:990–1000. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paik KY, Lee IK, Lee YS, Sung NY, Kwon TS. Clinical implications of systemic inflammatory response markers as independent prognostic factors in colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:65–73. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.46.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cannon NA, Meyer J, Iyengar P, Ahn C, Westover KD, Choy H, Timmerman R. Neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as prognostic factors after stereotactic radiation therapy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:280–5. doi: 10.1097/jto.0000000000000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferroni P, Riondino S, Formica V, Cereda V, Tosetto L, La Farina F, Valente MG, Vergati M, Guadagni F, Roselli M. Venous thromboembolism risk prediction in ambulatory cancer patients: clinical significance of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio and platelet/lymphocyte ratio. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1234–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai Q, Castro Santa E, Rico Juri JM, Pinheiro RS, Lerut J. Neutrophil and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as new predictors of dropout and recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular cancer. Transpl Int. 2014;27:32–41. doi: 10.1111/tri.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang GM, Zhu Y, Luo L, Wan FN, Zhu YP, Sun LJ, Ye DW. Preoperative lymphocyte-monocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as predictors of overall survival in patients with bladder cancer undergoing radical cystectomy. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:8537–43. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Iwasaki Y, Kubota K. Combination of platelet count and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio is a useful predictor of postoperative survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:401–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You J, Zhu GQ, Xie L, Liu WY, Shi L, Wang OC, Huang ZH, Braddock M, Guo GL, Zheng MH. Preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio is a valuable prognostic biomarker in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:25516–27. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodelon C, Polley MY, Kemp TJ, Pesatori AC, McShane LM, Caporaso NE, Hildesheim A, Pinto LA, Landi MT. Circulating levels of immune and inflammatory markers and long versus short survival in early-stage lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2073–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan JC, Chan DL, Diakos CI, Engel A, Pavlakis N, Gill A, Clarke SJ. The Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio is a Superior Predictor of Overall Survival in Comparison to Established Biomarkers of Resectable Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000001743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Passardi A, Scarpi E, Cavanna L, Dall’Agata M, Tassinari D, Leo S, Bernardini I, Gelsomino F, Tamberi S, Brandes AA, Tenti E, Vespignani R, Frassineti GL, et al. Inflammatory indexes as predictors of prognosis and bevacizumab efficacy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:33210–9. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szkandera J, Pichler M, Absenger G, Stotz M, Arminger F, Weissmueller M, Schaberl-Moser R, Samonigg H, Kornprat P, Stojakovic T, Avian A, Gerger A. The elevated preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio predicts decreased time to recurrence in colon cancer patients. Am J Surg. 2014;208:210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi WJ, Cleghorn MC, Jiang H, Jackson TD, Okrainec A, Quereshy FA. Preoperative Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio is a Better Prognostic Serum Biomarker than Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Patients Undergoing Resection for Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:S603–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neofytou K, Smyth EC, Giakoustidis A, Khan AZ, Williams R, Cunningham D, Mudan S. The Preoperative Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio is Prognostic of Clinical Outcomes for Patients with Liver-Only Colorectal Metastases in the Neoadjuvant Setting. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:4353–62. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4481-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son HJ, Park JW, Chang HJ, Kim DY, Kim BC, Kim SY, Park SC, Choi HS, Oh JH. Preoperative plasma hyperfibrinogenemia is predictive of poor prognosis in patients with nonmetastatic colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2908–13. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-2968-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toiyama Y, Inoue Y, Saigusa S, Kawamura M, Kawamoto A, Okugawa Y, Hiro J, Tanaka K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. C-reactive protein as predictor of recurrence in patients with rectal cancer undergoing chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:5065–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stotz M, Pichler M, Absenger G, Szkandera J, Arminger F, Schaberl-Moser R, Samonigg H, Stojakovic T, Gerger A. The preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio predicts clinical outcome in patients with stage III colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:435–40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin GN, Liu PP, Liu DY, Peng JW, Xiao JJ, Xia ZJ. Prognostic significance of the pre-chemotherapy lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer receiving FOLFOX chemotherapy. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:5. doi: 10.1186/s40880-015-0063-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen XL, Yao GQ, Liu JR. Prognostic value of pre-operative NLR,d-NLR,PLR and LMR for predicting clinical outcome in surgical colorectal cancer patients. Chin J Immun. 2015;31:1389–93. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-484X.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carruthers R, Tho LM, Brown J, Kakumanu S, McCartney E, McDonald AC. Systemic inflammatory response is a predictor of outcome in patients undergoing preoperative chemoradiation for locally advanced rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e701–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li ZM, Peng YF, Du CZ, Gu J. Colon cancer with unresectable synchronous metastases: the AAAP scoring system for predicting the outcome after primary tumour resection. Colorectal Dis. 2015;18:255–63. doi: 10.1111/codi.13123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori K, Toiyama Y, Saigusa S, Fujikawa H, Hiro J, Kobayashi M, Ohi M, Araki T, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, Mohri Y, Kusunoki M. Systemic Analysis of Predictive Biomarkers for Recurrence in Colorectal Cancer Patients Treated with Curative Surgery. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:2477–87. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3648-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y, Jia H, Yu W, Xu Y, Li X, Li Q, Cai S. Nomograms for predicting prognostic value of inflammatory biomarkers in colorectal cancer patients after radical resection. Int J Cancer. 2016;139:220–31. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ni XF, Wu P, Wu J, Ji M, Shao YJ, Zhou WJ, Jiang JT, Wu CP. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio as a predictor of survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9:5525–34. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozawa T, Ishihara S, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Tanaka J, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Kawai K, Nozawa H, Kazama S, Yamaguchi H, Sunami E, Kitayama J, et al. The preoperative platelet to lymphocyte ratio is a prognostic marker in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1165–71. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao WW, Zhang LN, You KY, Huang R, Yu X, Ding PR, Gao YH. A Low Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio Predicts Unfavorable Prognosis in Pathological T3N0 Rectal Cancer Patients Following Total Mesorectal Excision. J Cancer. 2015;6:616–22. doi: 10.7150/jca.11727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu QQ, Hu GY, Zhang MS, Qiu H, Yuan XL. Prognostic value of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in metastatic colorectal cancer. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2016;45:136–40. doi: 10.3870/j.issn.1672-0741.2016.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozawa T, Ishihara S, Kawai K, Kazama S, Yamaguchi H, Sunami E, Kitayama J, Watanabe T. Impact of a lymphocyte to monocyte ratio in stage IV colorectal cancer. J Surg Res. 2015;199:386–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui YS, Chen XL, Zhou HL. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic factor for colorectal cancer. Journal of new medicine. 2015;46:685–9. doi: 10.3969/g.issn.0253-9802.2015.10.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neal CP, Cairns V, Jones MJ, Masood MM, Nana GR, Mann CD, Garcea G, Dennison AR. Prognostic performance of inflammation-based prognostic indices in patients with resectable colorectal liver metastases. Med Oncol. 2015;32:144. doi: 10.1007/s12032-015-0590-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neofytou K, Smyth EC, Giakoustidis A, Khan AZ, Cunningham D, Mudan S. Elevated platelet to lymphocyte ratio predicts poor prognosis after hepatectomy for liver-only colorectal metastases, and it is superior to neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as an adverse prognostic factor. Med Oncol. 2014;31:239. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ying HQ, Deng QW, He BS, Pan YQ, Wang F, Sun HL, Chen J, Liu X, Wang SK. The prognostic value of preoperative NLR, d-NLR, PLR and LMR for predicting clinical outcome in surgical colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2014;31:305. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu H, Du X, Sun P, Xiao C, Xu Y, Li R. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent prognostic factor for resectable colorectal cancer. [Article in Chinese] Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2013;33:70–3. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-4254.2013.01.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zou ZY, Liu HL, Ning N, Li SY, Du XH, Li R. Clinical significance of pre-operative neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors for patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:2241–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duan ZH, Peng K, Hu LJ. Effect of preoperative platelet and lymphocyte ratio on prognosis of primary colorectal cancer in elderly patients. The Practical Journal of Cancer. 2014;29:750–2. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5930.2014.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo Y, Yue TQ, Fu YS, Cheng ZJ, Zhang K, Rao H. Factors affecting of the efficacy of elderly primary colorectal cancer after surgery. The Practical Journal of Cancer. 2014;29:1005–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-5930.2014.08.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baranyai Z, Krzystanek M, Josa V, Dede K, Agoston E, Szasz AM, Sinko D, Szarvas V, Salamon F, Eklund AC, Szallasi Z, Jakab F. The comparison of thrombocytosis and platelet-lymphocyte ratio as potential prognostic markers in colorectal cancer. Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:483–90. doi: 10.1160/TH13-08-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Ohtani H, Sakurai K, Yamazoe S, Kimura K, Toyokawa T, Amano R, Tanaka H, Muguruma K, Hirakawa K. Prognostic significance of the lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9966–73. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song A, Eo W, Lee S. Comparison of selected inflammation-based prognostic markers in relapsed or refractory metastatic colorectal cancer patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12410–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i43.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun ZQ, Han XN, Wang HJ, Tang Y, Zhao ZL, Qu YL, Xu RW, Liu YY, Yu XB. Prognostic significance of preoperative fibrinogen in patients with colon cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8583–91. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozdemir Y, Akin ML, Sucullu I, Balta AZ, Yucel E. Pretreatment neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic aid in colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:2647–50. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.6.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perisanidis C, Kornek G, Poschl PW, Holzinger D, Pirklbauer K, Schopper C, Ewers R. High neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is an independent marker of poor disease-specific survival in patients with oral cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30:334. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lino-Silva LS, Salcedo-Hernandez RA, Ruiz-Garcia EB, Garcia-Perez L, Herrera-Gomez A. Pre-operative Neutrophils/Lymphocyte Ratio in Rectal Cancer Patients with Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy. Med Arch. 2016;70:256–60. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2016.70.256-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, Al-Mubarak M, Vera-Badillo FE, Hermanns T, Seruga B, Ocana A, Tannock IF, Amir E. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1204–12. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-14-0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goubran HA, Stakiw J, Radosevic M, Burnouf T. Platelet-cancer interactions. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2014;40:296–305. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1370767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orellana R, Kato S, Erices R, Bravo ML, Gonzalez P, Oliva B, Cubillos S, Valdivia A, Ibanez C, Branes J, Barriga MI, Bravo E, Alonso C, et al. Platelets enhance tissue factor protein and metastasis initiating cell markers, and act as chemoattractants increasing the migration of ovarian cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:290. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1304-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Minami T, Minami T, Shimizu N, Yamamoto Y, De Velasco M, Nozawa M, Yoshimura K, Harashima N, Harada M, Uemura H. Identification of Programmed Death Ligand 1-derived Peptides Capable of Inducing Cancer-reactive Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes From HLA-A24+ Patients With Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Immunother. 2015;38:285–91. doi: 10.1097/cji.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marech I, Ammendola M, Sacco R, Sammarco G, Zuccala V, Zizzo N, Leporini C, Luposella M, Patruno R, Filippelli G, Russo E, Porcelli M, Gadaleta CD, et al. Tumour-associated macrophages correlate with microvascular bed extension in colorectal cancer patients. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20:1373–80. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McMillan DC. Systemic inflammation, nutritional status and survival in patients with cancer. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:223–6. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832a7902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–5. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.