Abstract

The overjustification hypothesis suggests that extrinsic rewards undermine intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic rewards are common in strengthening behavior in persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities; we examined overjustification effects in this context. A literature search yielded 65 data sets permitting comparison of responding during an initial no-reinforcement phase to a subsequent no-reinforcement phase, separated by a reinforcement phase. We used effect sizes to compare response levels in these two no-reinforcement phases. Overall, the mean effect size did not differ from zero; levels in the second no-reinforcement phase were equally likely to be higher or lower than in the first. However, in contrast to the overjustification hypothesis, levels were higher in the second no-reinforcement phase when comparing the single no-reinforcement sessions immediately before and after reinforcement. Outcomes consistent with the overjustification hypothesis were somewhat more likely when the target behavior occurred at relatively higher levels prior to reinforcement.

Keywords: extrinsic reinforcement, intellectual and developmental disabilities, intrinsic motivation, overjustification effect

The merits of reinforcement procedures in educational settings have been debated for decades, and a common criticism of these procedures centers on what is often termed the overjustification hypothesis (Bem, 1972). The overjustification hypothesis predicts that rewards delivered by an external agent to engage in an activity reduce subsequent, internal, motivation to engage in that activity after explicit extrinsic rewards have been discontinued. By definition, an overjustification effect is manifest if levels of behavior following discontinuation of reward are lower than levels of behavior prior to reward.

Investigators have typically examined overjustification effects using between-group comparisons. These studies have frequently involved delayed consequences whose effectiveness as reinforcers had not been established. In one of the first studies on the topic, Deci (1971) rewarded college students’ performance on a number of tasks with either money or verbal rewards. The delivery of money appeared to negatively affect performance after discontinuation of monetary rewards, whereas participants provided with verbal rewards showed an increase in performance after discontinuation of verbal rewards relative to baseline responding. Greene and Lepper (1974) investigated the effects of expected and unexpected rewards on activity interest, defined as time spent engaging in an activity. They assigned typically developing school-aged children to an unexpected-reward group, an expected-reward group, or a no-reward group. For both reward groups, the external reward was a “good-player award” consisting of the child’s name and the school’s name engraved on a gold star. Task engagement was significantly lower after rewards relative to before rewards, but only when the reward was expected.

Subsequent studies have investigated the overjustification effect in educational settings using methods similar to Deci (1971) and Greene and Lepper (1974), but varied task and reward types, as well as the contingency between behavior and reward. Numerous reviews and meta-analyses have since focused on determining if and when the overjustification effect occurs and what variables predict the absence, presence, and degree of such an effect. For example, Cameron and Pierce (1994) separately reviewed studies that used group designs to determine reward effects on behavior and studies that used single-case research methodology to assess direct-acting effects of reinforcers on behavior. Studies using single-case designs were included only when a reinforcement effect was demonstrated by an increase in behavior during the reinforcement phase. Their meta-analysis revealed no consistent detrimental effect of either reinforcement or rewards on motivation. Results from group designs indicated that verbal rewards did not produce a decrease in time spent on task or enjoyment, gauged via questionnaires on self-reported interest in the activity. Tangible rewards produced no effect on performance when they were delivered unexpectedly as opposed to when they were announced in advance. However, expected rewards were not detrimental when they were delivered contingent on task performance. Results from the single-case design studies indicated that reinforcement led to an increase in time spent on the task in the second no-reinforcement phase relative to the first.

Few studies have examined overjustification effects using single-case research methodology to compare baseline levels of responding on educational tasks to levels after discontinuation of reinforcement. Bright and Penrod (2009) did not observe overjustification effects when academic task engagement of typically developing children was followed with either verbal praise or stimuli established as either reinforcing or nonreinforcing via reinforcer assessment. Other single-case analyses of the overjustification effect have produced similar results, suggesting that when contingent reinforcement is delivered, an overjustification effect is unlikely (e.g., Feingold & Mahoney, 1975; Vasta & Stirpe, 1979).

To date, no research synthesis of the overjustification effect has specifically focused on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, yet a specific focus on this population seems warranted. Procedures based on applied behavior analysis are widely implemented with this population, as evidenced by reviews suggesting strong support for these interventions (e.g., Virués-Ortega, 2010), as well as backing by scientific, professional, and government organizations such as the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology (Volkmar et al., 2014), Centers for Disease Control (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015), and U.S. Surgeon General (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). As programmed reinforcement contingencies are a behavior-analytic technique commonly implemented with this population (Vollmer & Hackenberg, 2001), a focused examination seems highly relevant. The purpose of the current study was therefore to determine the likelihood of outcomes consistent with the overjustification hypothesis when reinforcement contingencies are withdrawn for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. This analysis was conducted by extracting data on response levels from published cases containing such an arrangement. Secondary analyses were conducted to (a) determine the likelihood of such an effect when data samples included only the periods immediately before and immediately after the reinforcement contingency, and (b) determine whether certain response or contingency variations consistently predicted decreases in response levels after the withdrawal of reinforcement.

METHOD

We conducted an electronic search of six journals that routinely publish preference and reinforcer assessment studies with persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Reinforcer assessments seemed ideal for this analysis because they permit a direct comparison of response levels before and after the introduction of a reinforcement contingency. The journals included Behavioral Interventions, Behavior Modification, the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, the Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, and Research in Developmental Disabilities. We used the search function on each journal’s website using the key words “reinforcer assessment” anywhere in the article, from 1994 through 2014. The search identified 265 candidate studies, which we reviewed for inclusion using the criteria described below.

Inclusion Criteria

We included individual data sets in the analysis if they had the following characteristics: (a) reinforcer assessment data with a schedule of positive reinforcement for a previously mastered task (i.e., data sets in the context of acquisition were excluded, as the participant may have lacked the skills to complete the task prior to reinforcement); (b) a minimum of one ABA design (A = no-reinforcement, B = reinforcement) with a clear reinforcement effect (i.e., the authors of the study concluded that levels of behavior during the B phase were clearly and consistently above the A phases) and at least three data points in all phases; (c) mean levels of responding in the initial no-reinforcement phase that exceeded zero (i.e., data sets with no responding during the initial no-reinforcement phase were excluded because one cannot observe a postreinforcement decrease below zero); and (d) responding that was measured in terms of response rate (or frequency), percentage of intervals (or sessions), or percentage of trials in which behavior occurred. Moreover, all participants had to have been diagnosed with an intellectual or developmental disability. Using these criteria, we identified 65 qualifying data sets from 27 studies. Table 1 lists each participant from each study, along with task type, reinforcement schedule, and reinforcer type for each data set included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Study of Origin, Participant Name, Task, Reinforcement Schedule, and Reinforcer Type for Each Data Set Included in the Analysis

| Study | Participant | Task | Schedule | Reinforcer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay et al., 2013 | Alex | Put block in bowl | FR1 | Social |

| Kyle | Put block in bowl | FR1 | Social | |

| Sofia | Put block in bowl | FR1 | Social | |

| DeLeon et al., 2014 | Jillian | Sort office supplies | FR1 | Leisure |

| DeLeon & Iwata, 1996 | Jack | Press microswitch | FR1 | Edible |

| Rupert | Stamp paper | FR1 | Edible | |

| DeLeon et al., 1999 | Charlene | Brush hair | FR1 | Leisure |

| Robbie | Match coins | FR1 | Leisure | |

| DeLeon et al., 1997 | Alex | Fold towels | FR1 | Leisure |

| Sheila | Dry hands | FR1 | Leisure | |

| Frank-Crawford et al., 2012 | Glenn | Place paper in bin | FR1 | Edible |

| Graff & Ciccone, 2002 | Andy | Press button | VR5/10 | Edible |

| George | Press button | VR5/10 | Edible | |

| James | Press button | VR5/10 | Edible | |

| Graff & Gibson, 2003 | Christopher | Press button | VR10 | Edible |

| Connor | Press button | VR10 | Edible | |

| James | Press button | VR10 | Edible | |

| Graff et al., 2006 | Charlie | Sort silverware | FR1 | Edible |

| James | Stamp paper | FR1 | Edible | |

| Graff & Larsen, 2011 | Chris | Sort silverware | FR3 | Edible |

| Jess | Sort silverware | FR3 | Edible | |

| Matt | Sort silverware | FR12 | Edible | |

| Veronica | Sort silverware | FR5 | Edible | |

| Groskreutz & Graff, 2009 | Derrick (1) | File paper | FI30s | Edible |

| Luis (1) | File paper | FI30s | Edible | |

| Andrew (2) | Sort silverware | FI30s | Edible | |

| Derrick (2) | Fill dispenser | FI30s | Edible | |

| Stewart (2) | Sort silverware | FI30s | Edible | |

| Hanley et al., 2003 | Rob | Stamp/stuff paper | FR1 | Leisure |

| Higbee et al., 2000 | Brenda | Press microswitch | FR5 | Edible/Leisure |

| Casey | Press microswitch | FR15 | Edible | |

| Daryl | Press microswitch | FR2 | Leisure | |

| Marcy | Press microswitch | FR3 | Edible/Leisure | |

| Marvin | Press microswitch | FR6 | Edible | |

| Higbee et al., 2002 | Corey | Sort socks | Varied | Edible |

| Kyle | Sort socks | Varied | Edible | |

| Steven | Sort socks | Varied | Edible | |

| Logan et al., 2001 | Jason | Press microswitch | FR1 | Leisure |

| Michael | Press microswitch | FR1 | Leisure | |

| Robert | Press microswitch | FR1 | Edible | |

| Najdowski et al., 2005 | Ethan | Transfer beans | FR1 | Edible |

| Sam | Put block in bucket | FR1 | Edible | |

| Nuernberger et al., 2012 | Cade | Sort silverware | FR4 | Social |

| Natasha | Sort items | FR4 | Social | |

| Nigel | Sort blocks | FR3 | Social | |

| Penrod et al., 2008 | Cedar | Deposit bean | PR | Edible |

| Sam | Track/touch card | PR | Edible | |

| Piazza et al., 1997 | Ty | Touch card | FR1 | Leisure |

| Piazza et al., 1998 | Jerry | Press switch | FR1 | Social |

| Tom | Press switch | FR1 | Social | |

| Roane et al., 2005 | Floyd | Sort envelopes | PR | Leisure |

| Melvin | Add single digits | PR | Leisure | |

| Taravella et al., 2000 | Brad | Put block in bucket | FR1 | Leisure |

| Mark | Stand In-square | FR1 | Leisure | |

| Tarbox et al., 2007 | Sam | Press microswitch | FR1 | Leisure |

| Seth | String beads | FR1 | Leisure | |

| Tessing et al., 2006 | Justin | Add single digits | FR2 | Leisure |

| Kyle | Add single digits | FR2 | Leisure | |

| Thompson & Iwata, 2000 | Biz | Open container | FR1 | Edible |

| Deb | Open container | FR1 | Edible | |

| Samantha | Open container | FR1 | Edible | |

| Wilder et al., 2008 | Alex | Sort cards | FR2 | Leisure |

| Bill | Sort cards | FR2 | Leisure | |

| Don | Sort cards | FR2 | Leisure | |

| Zarcone et al., 1996 | Ray (2) | Stack cups | FR1 | Leisure |

Interobserver agreement (IOA)

From the 265 possible studies discovered in the initial search, a second reviewer (i.e., master’s or doctoral-level behavior analyst) coded 89 articles (33.6%) to determine if each data set met the inclusion criteria. The percentage of data sets in each article with agreement averaged 99% (range, 66.7% to 100.0%). Across articles, there was a total of four disagreements relating to participant diagnosis, appropriate ABA design, or presence of a reinforcement effect. For each disagreement, the two raters discussed the discrepancy and reached a consensus.

Data Analysis

Currently, there is no consensus on how to accurately derive quantitative estimates of treatment effects for studies using single-case research methodology (Shadish, Hedges, Horner, & Odom, 2015). What Works Clearinghouse has recommended the use of multiple computational procedures to assess the magnitude of treatment effects with the suggestion that stronger conclusions may be drawn when similar findings are observed across indices (Kratochwill et al., 2010). The present study computed treatment effects through use of both parametric and nonparametric metrics (Hedge’s g and Tau-U, respectively, described below).

Data extraction

GetData Graph Digitizer 2.22 was used to extract data points for each qualifying data set. GetData Graph Digitizer is a software program used for determining precise values of each data point in a digitized graph or plot. Using scanned JPEG format electronic images, X–Y data points were obtained from each qualifying data set by forming a digitized plot that overlapped the data display and assigning a range of values for the X and Y axes. From there, the program allows the researcher to identify the values of each data point given in scientific notation. We then calculated effect sizes (described below) with the known Y values to compare response levels before and after the reinforcement phase.

Effect size calculations and meta-analysis

Hedges’ g. We used Hedges’ g as the parametric measure of effect size. Typically, Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988) is used in meta-analyses to reflect the difference between the means of two groups divided by the pooled within-group standard deviation (e.g., Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999). Hedges’ g is based on Cohen’s d, but corrects for bias in small sample sizes (Cumming, 2012; Lakens, 2013). In the current analysis, we compared the mean levels of responding in the first and second no-reinforcement phases. We included only the first two no-reinforcement phases in each data set to account for possible reinforcement history effects across further phases and excluded one data set because we were unable to identify which of multiple reinforcer assessments came first, as they were depicted on separate graphs. We calculated the means and standard deviations using the data point values given by GetData Graph Digitizer, and used these to calculate g values. The formula used to calculate effect sizes was:

This formula was calculated with respect to the first and second no-reinforcement phases, where M1 and M2 are the respective means, SD1 and SD2 are the respective standard deviations, and n is the total number of data points being compared (i.e., n1 + n2). A positive g value reflects a mean decrease in responding in the second no-reinforcement phase relative to the first, an outcome consistent with the overjustification hypothesis. A negative g value, by contrast, reflects a mean increase in responding in the second no-reinforcement phase relative to the first, an outcome inconsistent with the overjustification hypothesis.

We also reanalyzed these outcomes using only the last three data points of each phase following recommendations from Marquis et al. (2000). Reinforcer assessments are typically arranged as within-series repeated measures, and those repeated measures are often associated with within-phase changes in response levels (i.e., transition states). For example, immediately after the discontinuation of reinforcement contingencies, response levels may still be influenced by the recent local history of reinforcement, and it may take several sessions for levels to stabilize as a result of the newly introduced contingency. One might therefore argue that response levels at stability are a more accurate reflection of intrinsic interest than the entire phase that includes behavior in transition. To minimize the potential influence of transition states, the reanalyses considered only the last three sessions of the first and second no-reinforcement phases.

Most studies that have examined the detrimental effects of extrinsic reinforcement on intrinsic motivation used between-subject experimental designs. In many of these studies, means of reward and no-reward groups were examined only once prior to introducing the independent variable (reward vs. no reward) and only once following the independent variable manipulation. To make the current results comparable to investigations conducted in this manner, we additionally examined data from the last session of the first no-reinforcement phase and the first session of the second no-reinforcement phase. Because effect size calculations are not possible for single data points, the data were statistically compared using a paired-sample t-test.

Tau-U analysis

The percent of nonoverlapping data (PND) has been commonly used to assess treatment effects in single-case research (Maggin, O’Keefe, & Johnson, 2011). However, PND does not describe the magnitude of treatment effects between phases and is influenced by trend and outliers (Wolery, Busick, Reichow, & Barton, 2010). Therefore, we used Tau-U, a distribution-free nonparametric data overlap metric that can control for baseline trend, as the overlap method (see Parker, Vannest, Davis, & Sauber, 2011, for computation). An additional benefit of using Tau-U is that the variance of Tau can be calculated and used to aggregate the effect sizes in a traditional meta-analytic model (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009). We calculated Tau-U using all data and Tau-U using only the last three data points for comparison with the g results via an online calculator developed by Vannest, Parker, and Gonen (2011) at singlecaseresearch.org.

Meta-analysis

We estimated a random-effects meta-analysis model using the Tau-U for all data, Tau-U for the last three data points, and variance of Tau values in the Metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010) in R (R Core Team, 2013). We used a random-effects model because our goal was to generalize the findings beyond the studies in the current analysis (Scammacca, Roberts, Vaughn, & Stuebing, 2015) and to accurately model significant heterogeneity. A positive effect size would indicate that the levels of responding in the first no-reinforcement phase were higher than the second, which would be consistent with the overjustification hypothesis. However, a negative effect size would indicate that the levels of responding in the second no-reinforcement phase were higher than the first, suggesting that the overjustification effect was not observed.

Secondary analyses

We conducted secondary analyses to identify the conditions under which the delivery of known reinforcers was more likely to produce levels of behavior below initial baseline levels after reinforcement had been discontinued. Three of these analyses consisted of examining effect sizes as a function of reinforcer type (edible, leisure, social), schedule of reinforcement, and task type (a functional task that promoted skill development—e.g., sorting silverware, brushing hair—vs. nonfunctional task—e.g., button pressing). None of these analyses produced significant differences (data available upon request).

A fourth analysis examined the strength of the relation between effect sizes and levels of responding before reinforcement was introduced. Cameron, Banko, and Pierce (2001) conducted a meta-analysis that suggested an outcome consistent with the overjustification hypothesis was more likely when the task was of “high initial interest” before rewards were arranged. However, interest levels generally were classified according to subjective self-reports, via questionnaire. The purpose of our analysis was to determine if effects consistent with the overjustification hypothesis are more likely when the behavior occurs at a relatively high rate during the initial baseline, which may be a more objective approximation of high “initial interest.”

Absolute levels of responding are difficult to compare across individuals because of inherent differences in dependent variables (e.g., rate, frequency, percent intervals, etc.), tasks, participant abilities, and other variables. We therefore normalized initial levels of responding by transforming them into a proportion relative to the levels observed during the reinforcement periods (i.e., mean response levels of first no-reinforcement phase divided by mean response levels during the reinforcement phase). As such, higher proportions indicated that reinforcement increased responding by a lower percentage; lower proportions indicated that reinforcement increased responding by a higher percentage. A higher proportion is thus perhaps analogous to higher intrinsic interest (i.e., responding was already occurring at relatively higher levels prior to the introduction of reinforcement).

We examined the relation between this proportion and effect sizes for a subset of the total data sets—those for which the reinforcement phase consisted of only one schedule and one stimulus. We excluded data sets for which the reinforcement phase consisted of a concurrent schedule, a multielement design comparing multiple reinforcers, or if the schedule values varied within the reinforcement phase (e.g., FR 1 for the first three sessions, VR 3 for the next few sessions, etc.), as these factors may have diminished absolute levels of responding under the reinforcement contingency. After these exclusions, 25 of the 65 data sets remained for analysis. We then calculated a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient to examine the relation between those proportions and effect sizes. The analysis was then repeated with only the last three data points of the no-reinforcement and reinforcement phases. If higher proportions can be interpreted as higher intrinsic interest, and the detrimental effects of extrinsic reinforcement are more common for behavior of higher intrinsic interest, then one would expect a positive relation between proportions and effect sizes.

Data Extraction Accuracy and Interobserver Agreement

Data extraction accuracy

We evaluated the accuracy of the GetData Graph Digitizer 2.22 program in extracting numerical values by comparing the program’s output to known values of hypothetical data sets we constructed. We created three separate graphs in Excel™, containing 30 data points each (10 in Phase A, 10 in Phase B, and 10 in return to Phase A) ranging from 0.0 to 2.6 responses per min in graph one, 12.8 to 80.0 responses per min in graph two, and 92.0 to 189.3 responses per min in graph three. We converted the graphs to JPEG files, and entered them into the program using the same procedures described for graphs extracted from published papers. For each data point, we divided the actual value by the observed value from the program, and multiplied by 100. The percentage accuracy for each data point in all phases averaged 100.0%, 100.0%, and 99.0% accuracy for the first, second, and third graph, respectively.

IOA

From the data sets included in the analysis, a trained graduate student independently analyzed 33 (50.8%) via the computer program GetData Graph Digitizer 2.22. The second observer extracted the value of each of the last 3 data points in the first and second no-reinforcement phases. We used percentage agreement to calculate interrater reliability among scores, dividing the smaller value by the larger value and multiplying by 100. Mean percentage agreement was 87.3% (range of data points, 0.0% to 100.0%; range of data sets, 54.4% to 99.7%). The occasional low measure of IOA typically occurred for data points near zero, due to the precision of the program at extremely low values. Specifically, for each data set, each observer used the software to manually plot the axes and select the data points to capture. Depending on the number of pixels in the data set and the meticulousness of the observer, the same data point could be plotted at .00 and .01. This is a minuscule absolute difference, in terms of the overall effect size for the data set, but would result in 0% agreement for that data point. This occurred for 12 data points, or 6.1% of the total sample.

RESULTS

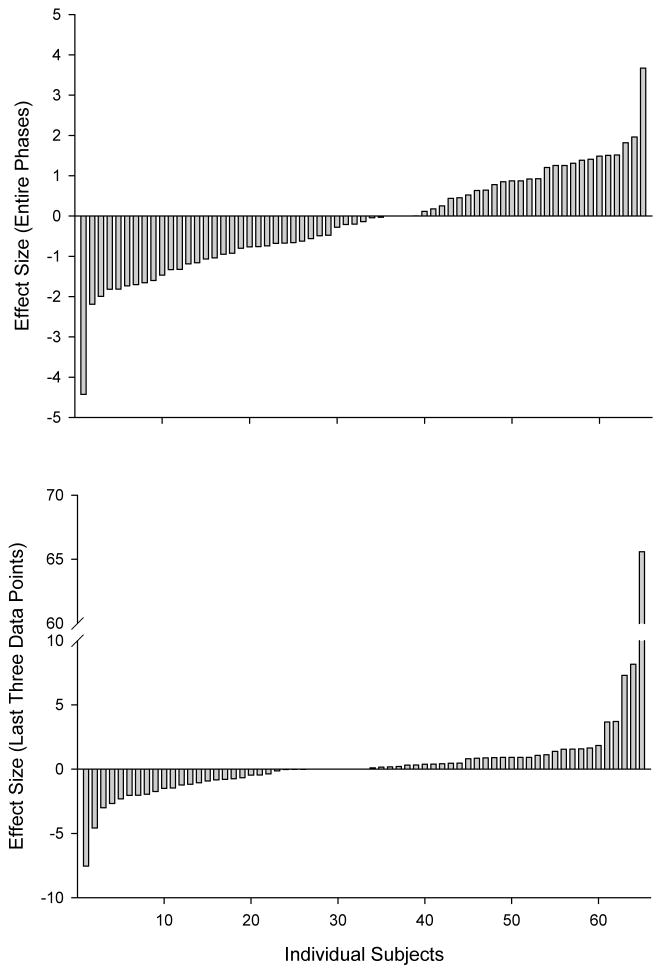

Figure 1 depicts the distribution of individual Hedges g effect sizes. The top panel represents all of the data from the first and second no-reinforcement phases. The values ranged from −4.43 to 3.67 with a mean effect size of −0.14 (median = −0.14, mode = 0.00). This distribution is slightly skewed below zero, a result inconsistent with the overjustification hypothesis. A single-sample t-test was conducted to test the hypothesis that the mean effect size differed from zero. The results of this analysis yielded a nonsignificant result (t = .90, p = .186), suggesting that the mean was not different from zero. That is, on average, effect sizes were just as likely to be positive as they were to be negative.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Hedges g effect sizes for each individual included in the analysis. Effect sizes in the top panel were calculated using the entire phase, effect sizes in the bottom panel were calculated using only the last three sessions of each phase.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 represents the data from only the last three sessions of the first and second no-reinforcement phases. The range of effect sizes was greater (−7.54 to 65.59), but the results were similar to the previous analysis with a mean effect size of 1.11 (median = 0.00, mode = 0.00). Although this distribution is skewed above zero, which would be consistent with the overjustification hypothesis, results of the single-sample t-test yielded a nonsignificant result (t = 1.06, p = .146). Furthermore, when this analysis was conducted again after excluding the one highly divergent outlier, the mean effect size was .10 (t = 1.02, p = .155), again suggesting that the mean was not different from zero. For this analysis, there were three datasets with no variation in responding in either no-reinforcement phase, precluding formal calculation of an effect size. However, for all three, the mean and standard deviation of the first no-reinforcement phase was identical to the second no-reinforcement phase, so we identified the effect size as 0.00. There were no such cases in the analysis that included data from the entire phase.

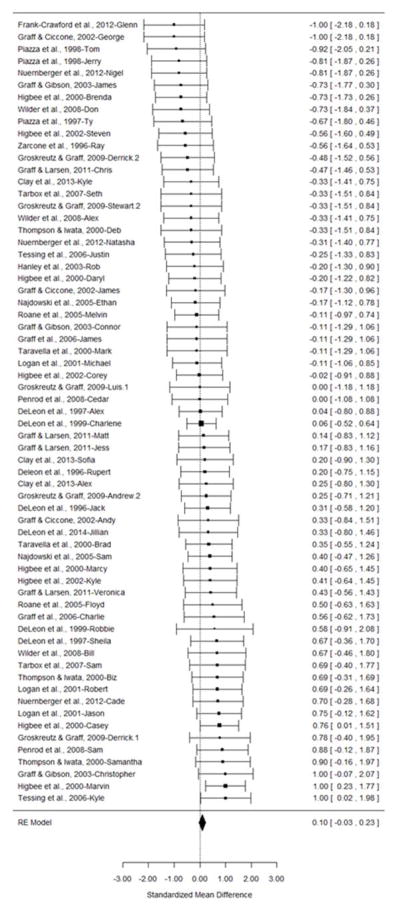

Figure 2 depicts the distribution of individual Tau-U effect sizes using the entire phase and the estimate of the mean effect size. The dark boxes in the forest plot denote the effect size for the individual data sets and the bars represent standard error. The dark diamond at the bottom represents the average weighted Tau-U effect size. The mean effect size across all 65 data sets was 0.099 (p =.14, 95% CI = −0.03, 0.23), which indicates results that are inconsistent with the overjustification hypothesis. Furthermore, when the individual effect sizes were calculated using only the last three data points in each phase, the mean effect was −0.032 (p = .69, 95% CI= −0.19, 0.12). Overall, the results from both meta-analysis models reveal no statistically significant differences between the first and second no-reinforcement phases.

Figure 2.

The forest plot distribution of individual effect sizes calculated using Tau-U and the estimate of the mean effect size. Effects sizes are calculated using the entire phase. Each row represents the data from a participant within a given study. For some participants, multiple data sets were available and a number was assigned to these participants to denote which data set was evaluated.

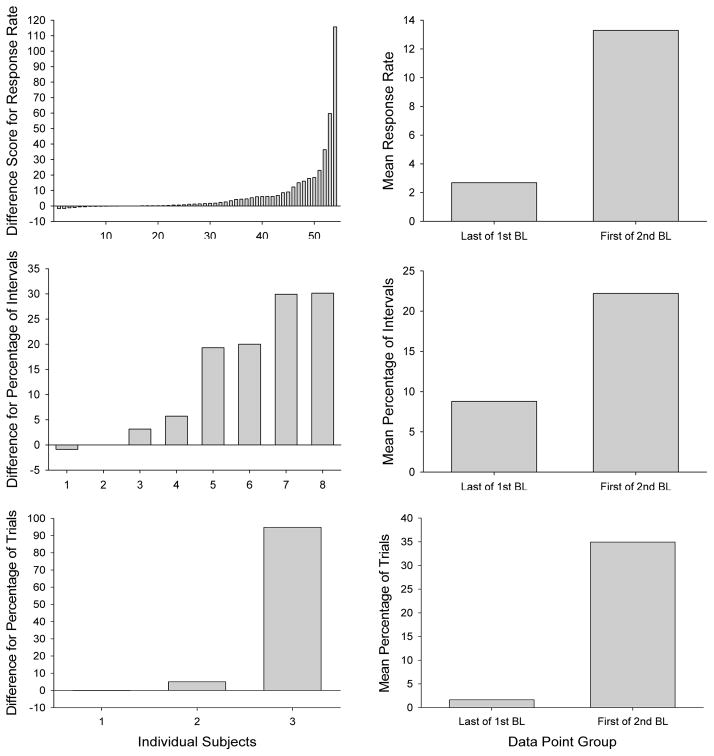

The three left panels of Figure 3 depict the distribution of difference scores for response rates (n = 54), percentage of intervals (n = 8), and percentage of trials (n = 3) when the last data point in the first no-reinforcement phase was subtracted from the first data point in the second no-reinforcement phase. The graphs show that difference scores, for each type of measurement, were strongly skewed above zero suggesting that values tended to be higher in the first session of the second no-reinforcement phase than in the last session of the first no-reinforcement phase, an outcome not consistent with the overjustification hypothesis.

Figure 3.

Distribution of difference scores (first point of second baseline – last point of first baseline) in the left panels and mean responding for the last point of the first no-reinforcement phase and first point of the second no-reinforcement phase in the right panels, across data sets depicting response rates (top panels), percentage of intervals (middle panels), and percentage of trials (bottom panels).

The three panels on the right side of Figure 3 depict the mean responding for the last point of the first no-reinforcement phase and first point of the second no-reinforcement phase. The upper right panel depicts mean response rates, which were significantly lower (p =.002) for the last point of the first no-reinforcement phase (M = 2.68) than the first point of the second no-reinforcement phase (M =13.29). The middle right panel depicts mean percentage of intervals, which were significantly lower (p = .011) for the last point of the first no-reinforcement phase (M = 8.79%) than the first point of the second no-reinforcement phase (M = 22.21%). The bottom right panel depicts mean percentage of trials, which were lower for the last point of the first no-reinforcement phase (M = 1.66%) than the first point of the second no-reinforcement phase (M = 34.9%), but the small sample size precluded a meaningful statistical analysis.

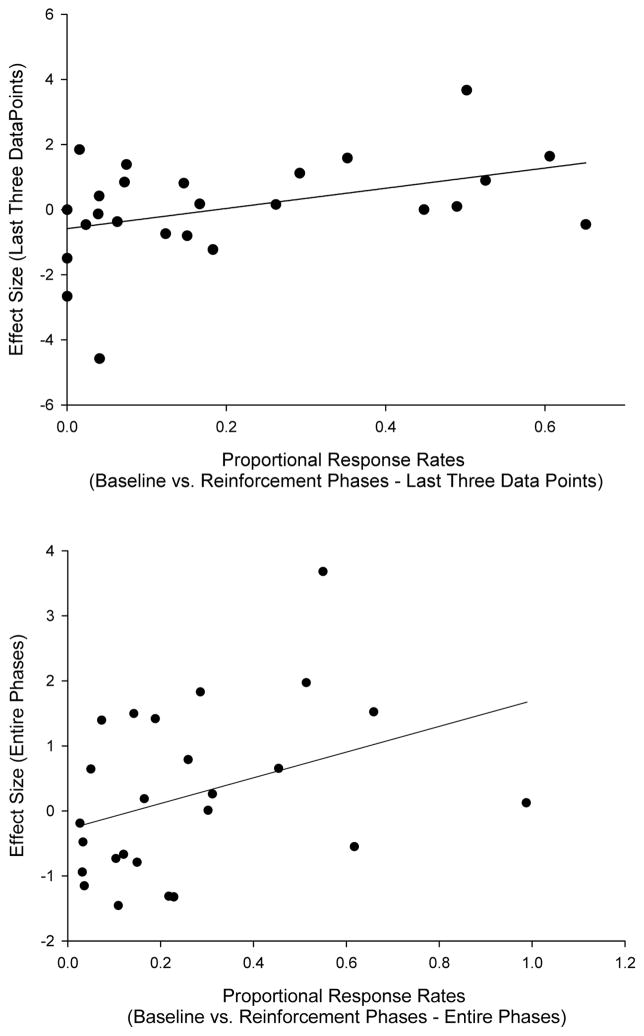

Figure 4 depicts scatterplots relating proportional response levels to effect size. The top panel represents all of the data from those phases. A Pearson product-moment correlation yielded a coefficient of .37 that approached significance (p = .065), with response levels accounting for 14.0% of the variance. The proportions in the bottom panel of Figure 4 represent data from only the last three sessions of the first no-reinforcement phase and the reinforcement phase. This relation yielded a significant r value of .41 (p =.041), with response levels accounting for 16.8% of the variance. These relations support the notion that effects consistent with the overjustification hypothesis are more likely to be observed for behavior that occurs at higher levels in the absence of extrinsic reinforcers (i.e., may be of higher “intrinsic interest”).

Figure 4.

Scatterplots depicting the relation between effect size and proportional response rates in baseline relative to response rates during reinforcement periods when the entire phases were used (top panel) and when only the last three data points of each phase were used (bottom panel). A line of best fit has been fitted to the data in each case.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the results suggest little evidence for a reliable overjustification effect on the behavior of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities when using a known reinforcer to increase levels of operant behavior. Both effect size metrics were just as likely to be negative (an outcome inconsistent with the overjustification hypothesis) as they were to be positive.

Analysis of local effects suggested that levels of responding tended to be higher immediately following the discontinuation of reinforcement than they were immediately prior to reinforcement (i.e., first data point of the second no-reinforcement phase was higher than the last data point of the first no-reinforcement phase) regardless of the measure. This outcome is contrary to the predictions of overjustification theory and results of many overjustification studies arranged in group designs. The results are more consistent with extinction effects, which are associated with a gradual reduction to the low levels observed prior to reinforcement.

We conducted subanalyses in an attempt to shed light on the circumstances under which overjustification effects may or may not be expected, including type of task, type of reinforcer, schedule of reinforcement, and level of responding in the absence of extrinsic reinforcers. The last was the only significant relation, suggesting that effect sizes tended to be somewhat higher when baseline levels of responding were proportionately higher in relation to reinforcement levels. These effects seem consistent with prior research on overjustification, which suggests that effects are more likely when tasks are inherently “interesting.” From a behavior-analytic perspective, this finding indicates an overjustification effect may be more likely for responses maintained in the absence of socially-mediated reinforcement. This observation seems particularly important in the context of work with persons with intellectual disabilities because behavior analysts generally only arrange reinforcement contingencies for responses that do not already occur at acceptable levels without programmed reinforcers.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, for this analysis, we used data from reinforcer assessments to directly compare responding before and after a reinforcement contingency. However, a limitation of evaluating reinforcer assessment data in the context of overjustification is that arbitrary responses may result in low levels of responding during the initial no-reinforcement phase. Observation of an overjustification effect necessarily requires initial prereinforcement responding to observe a decrement during postreinforcement responding. Thus, we only included datasets for which mean levels of responding in the initial no-reinforcement phase exceeded zero. Yet, our sample did include some datasets with zero responding during some sessions or a mean near zero, which may have affected the outcome. When analyzing the last three sessions of the first no-reinforcement phase, the percentage of sessions with zero responding averaged 20% across all data sets (range, 0% to 100%). Of the 65 data sets, 20 (31%) had at least one session with zero responding. Of those 20 data sets, the percentage of sessions with zero responding averaged 65% (range, 33% to 100%). When analyzing the entire first no-reinforcement phase, the percentage of sessions with zero responding averaged 19% across all data sets (range, 0% to 80%). Of the 65 data sets, 24 (37%) had at least one session with zero responding. Of those 24 data sets, the percentage of sessions with zero responding averaged 51% (range, 17% to 80%).

Second, our supplementary analyses using the last three data points of each phase were an attempt to capture levels of responding at steady state. This seemed a more representative and conservative approach. Sidman (1960) discussed that a steady state of responding should result in small amounts of variability within a phase, thus concluding that the effect of the independent variable had taken place. By evaluating effect sizes with the last three sessions of each phase, we presumed that any effect the independent variable would have on responding had occurred by that point. Still, an argument could be made that the last three data points in a phase do not always reflect a steady state, as single-case logic permits ending a phase on a clear trend as long as that trend is in a direction opposite from the anticipated effect of the independent variable.

Third, we used the between-group Hedges’ g for single-case design, thus treating data points as though they were independent. This approach was recommended by Busk and Serlin (1992), but has been questioned as computationally inaccurate as it does not account for serial dependence or trend, and is not directly comparable to the between-group standardized mean difference (Beretevas & Chung, 2008). In other words, Cohen’s (1988) rules of thumb for interpreting the magnitude of effect sizes do not apply when the metric is used for single-case design research. Therefore, we supplemented and supported the findings using Tau-U, a metric designed for single-case design.

There are a number of variables we did not examine, but could shed more light on the determinants of overjustification effects in future research. For example, many overjustification studies included a single reward period, whereas reinforcer assessments typically involve multiple exposures to the reinforcement contingencies. It remains possible that the duration of exposure to a reinforcement contingency might influence the likelihood of observing detrimental effects on responding. It might also be useful to examine the nature of that contingency. Eisenberger and Cameron (1996) noted differences between performance-dependent, completion-dependent, and response-independent arrangements for the delivery of rewards. Distinctions like these could perhaps be extracted more carefully from the literature on reinforcement procedures targeting persons with intellectual disabilities. Similarly, repeated exposure to the task itself could influence observed effects on responding. Peters and Vollmer (2014) demonstrated that extended exposure to preferred activities resulted in effects that were analogous to overjustification effects. A comparable decrease in engagement was observed across activities that had and had not been exposed to a reinforcement contingency.

Although we were unable to pinpoint circumstances in which the type of task produced an overjustification effect, it may be beneficial if future research could empirically evaluate overjustification effects with differences in the reinforcing effectiveness of the tasks. We defined “intrinsic interest” by the levels of responding during a no-reinforcement baseline relative to reinforcement. However, levels of nonreinforced responding are, at best, analogous to the construct “intrinsic interest” as there are several other variables that could influence response levels in the absence of programmed reinforcement (e.g., prior history of reinforcement). Also, as this measure is a ratio of responding during reinforcement, this precludes identification of intrinsic interest independent of reinforcement and should be considered a limitation. Future attempts to examine the influence of this variable might more directly gauge inherent interest in an activity, perhaps via a duration-based preference assessment (DeLeon, Iwata, Conners, & Wallace, 1999; Worsdell, Iwata, & Wallace, 2002).

Finally, it should be noted that the presence of an effect consistent with the overjustification hypothesis would not necessarily diminish the utility of arranging programmed reinforcement contingencies for persons with intellectual disabilities. In applied settings, reinforcement contingencies are arranged to establish or increase adaptive behaviors that do not already occur at sufficient levels. Perhaps some of these arrangements decrease intrinsic interest in the activity and the individual would not engage in those activities in the absence of reinforcement. On the other hand, programmed reinforcement contingencies are designed to establish repertories that can potentially place the individual in contact with more frequent reinforcement in the natural environment. For example, children are taught simple identity matching skills using contrived contingencies, not because identity matching should be something of inherent interest, but because the skills established serve as precursors for future instances of adaptive functioning. Whether the delivery of reinforcers enhances or detracts from a person’s intrinsic motivation at the local level is perhaps not as important as whether that reinforcement contingency facilitates the possibility of a more rewarding life.

Acknowledgments

The authors express our appreciation to Abbey Carreau-Webster and Jesse Dallery for assistance with preparation of the manuscript. Participation by IGD and MAF-C was supported by Grants R01 HD049753 and P01 HD055456 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NICHD.

Footnotes

A portion of this study was submitted by the first author to the Department of Psychology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master’s Degree.

Contributor Information

Allison Levy, The Kennedy Krieger Institute and University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

Iser G. DeLeon, University of Florida

Catherine K. Martinez, University of Florida

Nathalie Fernandez, University of Florida.

Nicholas A. Gage, University of Florida

Sigurđur Óli Sigurđsson, The Icelandic Centre for Research – RANNÍS.

Michelle A. Frank-Crawford, The Kennedy Krieger Institute and University of Maryland, Baltimore County

References

- Bem DJ. Self-perception theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1972;6:1–62. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60024-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beretvas SN, Chung H. An evaluation of modified R2-change effect size indices for single-subject experimental designs. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention. 2008;2:120–128. doi: 10.1080/17489530802446328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester, U.K: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bright CN, Penrod B. An evaluation of the overjustification effect across multiple contingency arrangements. Behavioral Interventions. 2009;24:185–194. doi: 10.1002/bin.284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busk PL, Serlin RC. Meta-analysis for single-case research. In: Kratochwill TR, Levin JR, editors. Single case research design and analysis: New directions for psychology and education. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 187–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J, Banko KM, Pierce WD. Pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: The myth continues. The Behavior Analyst. 2001;24:1–44. doi: 10.1007/BF03392017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron J, Pierce WD. Reinforcement, reward, and intrinsic motivation: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research. 1994;64:363–423. doi: 10.3102/00346543064003363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Treatment. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/treatment.html.

- Clay CJ, Samaha AL, Bloom SE, Bogoev BK, Boyle MA. Assessing preference for social interactions. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34:362–371. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G. Understanding the new statistics: effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. New York, NY: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1971;18:105–115. doi: 10.1037/h0030644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of intrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:627–668. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Chase JA, Frank-Crawford MA, Carreau-Webster AB, Triggs MM, Bullock CE, Jennett HK. Distributed and accumulated reinforcement arrangements: Evaluations of efficacy and preference. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:293–313. doi: 10.1002/jaba.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA. Evaluation of a multiple-stimulus presentation format for assessing reinforcer preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:519–533. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA, Conners J, Wallace MD. Examination of ambiguous stimulus preferences with duration-based measures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:111–114. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeon IG, Iwata BA, Roscoe EM. Displacement of leisure reinforcers by food during preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:475–484. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger R, Cameron J. Detrimental effects of reward: Reality or myth? American Psychologist. 1996;51:1153–1166. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.51.11.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold BD, Mahoney MJ. Reinforcement effects on intrinsic interest: Undermining the overjustification hypothesis. Behavior Therapy. 1975;6:367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(75)80111-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Crawford MA, Borrero JC, Nguyen L, Leon-Enriquez Y, Carreau-Webster AB, DeLeon IG. Disruptive effects of contingent food on high-probability behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2012;45:143–148. doi: 10.1901/jaba0012.45-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Ciccone FJ. A post hoc analysis of multiple-stimulus preference assessment results. Behavioral Interventions. 2002;17:85–92. doi: 10.1002/bin.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Gibson L. Using pictures to assess reinforcers in individuals with developmental disabilities. Behavior Modification. 2003;27:470–483. doi: 10.1177/0145445503255602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Gibson L, Galiatsatos GT. The impact of high- and low-preference stimuli on vocational and academic performances of youths with severe disabilities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:131–135. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.32-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff RB, Larsen J. The relation between obtained preference value and reinforcer potency. Behavioral Interventions. 2011;26:125–133. doi: 10.1002/bin.325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene D, Lepper MR. Effects of extrinsic rewards on children’s subsequent intrinsic interest. Child Development. 1974;45:1141–1145. doi: 10.2307/1128110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groskreutz MP, Graff RB. Evaluating pictorial preference assessment: The effect of differential outcomes on preference assessment results. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2009;3:113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2008.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley GP, Iwata BA, Roscoe EM, Thompson RH, Lindberg JS. Response-restriction analysis: II. Alteration of activity preferences. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:59–76. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higbee TS, Carr JE, Harrison CD. Further evaluation of the multiple-stimulus preference assessment. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21:61–73. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(99)00030-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higbee TS, Carr JE, Patel MR. The effects of interpolated reinforcement on resistance to extinction in children diagnosed with autism: A preliminary investigation. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2002;23:61–78. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(01)00092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM, Shadish WR. Single-case designs technical documentation. 2010 Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan KR, Jacobs HA, Gast DL, Smith PD, Daniel J, Rawls J. Preferences and reinforcers for students with profound multiple disabilities: Can we identify them? Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. 2001;13:97–122. doi: 10.1023/A:1016624923479. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maggin DM, O’Keefe BV, Johnson AH. A quantitative synthesis of single-subject meta-analysis in special education, 1985–2009. Exceptionality. 2011;19:109–135. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2011.565725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis JG, Horner RH, Carr EG, Turnbull AP, Thompson M, Behrens GA, … Doollahb A. A meta-analysis of positive behavior support. In: Gersten R, Schiller EP, Vaughn S, editors. Contemporary special education research: Syntheses of the knowledge base on critical instructional issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 137–178. [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski AC, Wallace MD, Penrod B, Cleveland J. Using stimulus variation to increase reinforcer efficacy of low preference stimuli. Behavioral Interventions. 2005;20:313–328. doi: 10.1002/bin.199. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nuernberger JE, Smith CA, Czapar KN, Klatt KP. Assessing preference for social interaction in children diagnosed with autism. Behavioral Interventions. 2012;27:33–44. doi: 10.1002/bin.1336. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RI, Vannest KJ, Davis JL, Sauber SB. Combining non-overlap and trend for single case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:284–299. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod B, Wallace MD, Dyer EJ. Assessing potency of high- and low-preference reinforcers with respect to response rate and response patterns. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2008;41:177–188. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2008.41-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters KP, Vollmer TR. Evaluations of the overjustification effect. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2014;23:201–220. doi: 10.1007/s10864-013-9193-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Hanley GP, Bowman LG, Ruyter JM, Lindauer SE, Saiontz DM. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza CC, Hanley GP, Fisher WW, Ruyter JM, Gulotta CS. On the establishing and reinforcing effects of termination of demands for destructive behavior maintained by positive and negative reinforcement. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1998;19:395–407. doi: 10.1016/S0891-4222(98)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Roane HS, Call NA, Falcomata TS. A preliminary analysis of adaptive responding under open and closed economies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:335–348. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.85-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scammacca NK, Roberts G, Vaughn S, Stuebing KK. A meta-analysis of interventions for struggling readers in grades 4–12: 1980–2011. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2015;48:369–390. doi: 10.1177/0022219413504995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Hedges LV, Horner RH, Odom SL. The role of between-case effect size in conducting, interpreting, and summarizing single-case research (NCER 2015-002) Washington, DC: National Center for Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2015. This report is available on the Institute website at http://ies.ed.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- Sidman M. Tactics of scientific research. Boston: Authors Cooperative. Inc; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Taravella CC, Lerman DC, Contrucci SA, Roane HS. Further evaluation of low-ranked items in stimulus-choice preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:105–108. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox RSF, Tarbox J, Ghezzi PM, Wallace MD, Yoo JH. The effects of blocking mouthing of leisure items on their effectiveness as reinforcers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:761–765. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.761-765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessing JL, Napolitano DA, McAdam DB, DiCesare A, Axelrod S. The effects of providing access to stimuli following choice making during vocal preference assessments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39:501–506. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.56-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RH, Iwata BA. Response acquisition under direct and indirect contingencies of reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:1–11. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Its causes and consequences. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2000;53:207–216. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: A report of the surgeon general. 1999 Retrieved from http://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/ps/retrieve/ResourceMetadata/NNBBHS.

- Vannest KJ, Parker RI, Gonen O. Single Case Research: web based calculators for SCR analysis. (Version 1.0) College Station, TX: Texas A&M University; 2011. [Web-based application] Retrieved Wednesday 20th July 2016. Available from http://www.singlecaseresearch.org/calculators/tau-u. [Google Scholar]

- Vasta R, Stirpe L. Reinforcement effects on three measures of children’s interest in math. Behavior Modification. 1979;3:223–244. doi: 10.1177/014544557932006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36:1–48. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v36/i03/ [Google Scholar]

- Virués-Ortega J. Applied behavior analytic intervention for autism in early childhood: Meta-analysis, meta-regression and dose-response meta-analysis of multiple outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar F, Siegel M, Woodbury-Smith M, King B, McCracken J, State M. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;52:237–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer TR, Hackenberg TD. Reinforcement contingencies and social reinforcement: Some reciprocal relations between basic and applied research. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:241–253. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder DA, Schadler J, Higbee TS, Haymes LK, Bajagic V, Register M. Identification of olfactory stimuli as reinforcers in individuals with autism: A preliminary investigation. Behavioral Interventions. 2008;23:97–103. doi: 10.1002/bin.257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolery M, Busick M, Reichow B, Barton EE. Comparison of overlap methods for quantitatively synthesizing single-subject data. Journal of Special Education. 2010;44:18–28. doi: 10.1177/0022466908328009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worsdell AS, Iwata BA, Wallace MD. Duration-based measures of preference for vocational tasks. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35:287–290. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarcone JR, Fisher WW, Piazza CC. Analysis of free-time contingencies as positive versus negative reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29:247–250. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]