Abstract

Objective

Targeted approaches for the treatment of severe and enduring anorexia nervosa (SE-AN) have been recommended, but there is no consensus definition of SE-AN to inform research and clinical practice. This study aimed to take initial steps toward developing an empirically based definition of SE-AN by characterizing associations among putative indicators of severity and chronicity in eating disorders.

Methods

Patients with AN (N=355) completed interviews and questionnaires at treatment admission and discharge; height and weight were assessed to calculate body mass index (BMI). Structural equation mixture modeling was used to test whether associations among potential indicators of SE-AN (illness duration, treatment history, BMI, binge eating, purging, quality-of-life) formed distinct subgroups, a single group with one or more dimensions, or a combination of subgroups and dimensions.

Results

A three-factor (dimensional), two-profile (categorical) mixture model provided the best fit to the data. Factor 1 included eating disorder behaviors; Factor 2 comprised quality-of-life domains; Factor 3 was characterized by illness duration, number of hospitalizations, and admission BMI. Profiles differed on eating disorder behaviors and quality-of-life, but not on indicators of chronicity or BMI. Factor scores, but not profile membership, predicted outcome at discharge from treatment.

Discussion

Data suggest that patients with AN can be classified on the basis of eating disorder behaviors and quality-of-life, but there was no evidence for a chronic subgroup of AN. Rather, indices of chronicity varied dimensionally within each class. Given that current definitions of SE-AN rely on illness duration, these findings have implications for research and clinical practice.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is notoriously difficult to treat, especially in adults with severe and enduring symptoms, that is, “SE-AN” (1). Treatment recommendations for SE-AN emphasize stabilization of symptoms, harm reduction, and improvements in psychosocial functioning (2, 3) rather than weight restoration and amelioration of disordered eating symptoms, which are recommended in the treatment of earlier stage AN presentations (4). However, there is no accepted, empirically based definition of SE-AN to guide clinical decision-making and research (2, 3). This issue is critical because SE-AN is associated with serious medical complications, frequent service utilization, and the highest mortality of any psychiatric illness (3), and engaging patients with SE-AN in treatment can be challenging (5).

Current definitions of SE-AN emphasize illness duration (1, 6–10), but thresholds vary, and illness duration likely is insufficient for characterizing SE-AN (2, 7, 11, 12). Among studies that have utilized illness duration to distinguish SE-AN from earlier stage AN, cutoffs of five (10), six (8), seven (1, 9), and ten (6) years have been reported. These thresholds have been based on clinical impressions and interpretations of existing literature, and evidence to support a categorical versus a dimensional approach to conceptualizing illness duration in AN is lacking. Furthermore, although additional criteria for SE-AN have been proposed including repeated treatment failures, low body mass index (BMI), binge eating, purging (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative misuse, diuretic misuse), psychosocial impairment, and poor quality-of-life (2, 7, 11, 12), few studies have incorporated these measures when defining groups, and the degree to which differences between SE-AN and earlier stage AN reflect qualitatively distinct subgroups versus a continuum of severity or chronicity is unknown.

The goal of the current study was to take the first steps toward developing an empirically based definition of SE-AN. Specifically, we sought to evaluate whether distinctions between SE-AN and earlier stage AN were represented by a categorical, dimensional, or hybrid categorical-dimensional model, and to identify criteria by which SE-AN might be characterized in clinical and research settings. To accomplish these aims, we utilized structural equation mixture modeling (SEMM), a statistical technique that incorporates aspects of factor analysis and latent class analysis to test whether associations among a set of observable criteria (e.g., illness duration, treatment failures, BMI) can be characterized in terms of distinct subgroups (e.g., SE-AN versus earlier stage AN), a single group with one or more dimensions, or a combination of subgroups and dimensions (13, 14). SEMM has been used to examine the latent structure of psychiatric diagnoses (15-20), including eating disorders (13), and to derive clinical cut-scores for psychiatric constructs (e.g., anxiety sensitivity) (21), but we are aware of no studies that have used SEMM to characterize population heterogeneity in the severity or chronicity of mental health conditions. Guided by prior theory and research, we examined the following variables as potential indicators of SE-AN: illness duration, number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms (as a proxy for treatment failure), BMI, binge eating, purging, and quality-of-life.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 355) were recruited from two academic medical center eating disorders programs in the eastern United States (Pittsburgh [n = 194]; New York [n = 161]). The Pittsburgh sample was enrolled in a longitudinal study examining the short-term naturalistic course of AN following inpatient or partial hospital treatment; study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described (22). Briefly, participants were aged ≥ 16 years and met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) (23) criteria for AN with two exceptions: 1) amenorrhea was not required and 2) individuals with a BMI < 17.5 who denied fear of fatness were included, consistent with descriptions of non-fat-phobic AN (24). The New York sample was drawn from a screening protocol examining the characteristics of patients with AN at admission to inpatient treatment on a research unit at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Exclusion criteria included acute suicidality or another Axis I disorder requiring immediate clinical attention. Participants were aged ≥ 14 years and met DSM-IV criteria for AN, with an exception for the amenorrhea criterion.

Demographic characteristics and indicators of SE-AN by site and in the combined sample are presented in Table 1. There were no between-site differences in age, sex, race, proportion of individuals with at least some college education, percent unemployed, or marital status. Participants recruited from Pittsburgh had significantly more eating disorder hospitalizations than the New York sample (t [333] = 2.33, p < .03). There were no other between-site differences with respect to indicators of SE-AN.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics and Indicators of SE-AN by Site and in the Combined Sample

| Characteristic | Pittsburgh (n=194)a | New York (n=161)b | Total (n=355)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (S.D.) | 26.5 (10.1) | 25.4 (7.8) | 26.0 (9.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 185 (95.4) | 135 (94.4) | 320 (95.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White, n (%) | 185 (95.4) | 132 (92.3) | 317 (94.1) |

| At least some college education, n (%) | 119 (61.3) | 100 (70.9) | 219 (65.4) |

| Unemployed, n (%) | 49 (25.3) | 44 (30.8) | 93 (27.6) |

| Never married, n (%) | 141 (73.1) | 117 (81.8) | 258 (76.8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (S.D.) | 15.7 (1.8) | 16.1 (1.8) | 15.9 (1.8) |

| Body mass index ≤ 14.0, n (%) | 32 (16.5) | 17 (12.4) | 49 (14.8) |

| Duration of illness (years), mean (S.D.) | 8.6 (9.0) | 9.0 (7.4) | 8.8 (8.4) |

| Duration of illness ≥ 10 years, n (%) | 71 (36.8) | 55 (39.6) | 126 (38.0) |

| Hospitalizations for eating disorder, mean (S.D.) | 3.2 (4.3) | 2.2 (2.7) | 2.8 (3.7) |

| Binge eating, n (%) | 40 (20.6) | 40 (29.2) | 80 (24.2) |

| Self-induced vomiting, n (%) | 75 (38.7) | 62 (44.6) | 137 (41.1) |

| Laxative or diuretic misuse, n (%) | 43 (22.2) | 30 (21.6) | 73 (21.9) |

| SF-36 role-physical, mean (S.D.) | 29.4 (36.0) | 32.4 (39.6) | 30.6 (37.5) |

| SF-36 social functioning, mean (S.D.) | 29.2 (23.9) | 31.5 (25.6) | 24.6 (30.1) |

| SF-36 emotional well-being, mean (S.D.) | 36.1 (18.7) | 36.1 (20.2) | 36.1 (19.3) |

One Pittsburgh participant did not report duration of illness, n = 193

New York cases with missing data were excluded from descriptive analyses; sample sizes in each cell were as follows: age, n = 142; sex, n = 143; race/ethnicity, n = 143; education, n = 141; employment, n = 143; marital status, n = 143; body mass index, n = 137; duration of illness, n = 139; hospitalizations, n = 141; binge eating, n = 137; self-induced vomiting, n = 139; laxative or diuretic misuse, n = 139; SF-36 role-physical, n = 132; SF-36 social functioning, n = 133; SF-36 emotional well-being, n = 133.

Cases with missing data were excluded.

Measures and Procedures

Assessments were completed within approximately two weeks of admission to inpatient (both sites) or partial hospital (Pittsburgh) treatment and at discharge. Assessors were bachelor’s, master’s or doctoral level research staff who were trained and supervised by licensed psychologists or psychiatrists at each site. Study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each site prior to data collection. Participants provided written informed consent or assent (individuals < 18 years).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (25)

The SCID-I is a well-studied diagnostic interview that has shown evidence of reliability in previous research [κ from .70 to 1.00; (26)]. It was used to assess lifetime and past month eating, mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders and self-reported duration of AN symptoms at admission to treatment.

Eating Disorder Examination [EDE (27)]

The EDE is an investigator-rated interview that was used at admission to document the frequency of binge eating and compensatory behaviors during the three months prior to assessment, and the severity of eating-related psychopathology on four subscales (i.e., Restraint, Eating Concern, Shape Concern, and Weight Concern) and a Global score calculated as the mean of the four subscales. The EDE was re-administered at discharge to assess changes in eating disorder symptoms during treatment. The EDE has shown evidence for adequate to excellent internal consistency and test-retest reliability (α = .68–.90; κ = .70–.99) (28).

RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0 [SF-36 (29)]

The SF-36 measures health-related quality-of-life in eight domains of physical and mental health functioning. Items are scored on a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Evidence for the reliability (α = 0.78–0.93) and validity of the SF-36 domains has been demonstrated in previous research (30, 31). Moreover, scores on an abbreviated version of the SF-36 (the SF-12) have been shown to predict changes in functional impairment and eating disorder severity over 12-month follow-up in patients with SE-AN (32). In the current study, we focused on three SF-36 domains with particular relevance to SE-AN: role limitations due to physical health problems (role-physical), social functioning, and emotional well-being.

Demographics and clinical history

An investigator-designed questionnaire was used to collect demographic data and clinical history including number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms and lowest BMI since age 12 (based on self-reported height and weight).

BMI (weight in kg/height in meters squared) was calculated from measures of weight and height collected at treatment admission and discharge. Participants were weighed on a digital scale in a hospital gown without shoes; height was measured using a stationary stature board.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 22 (33) and Mplus Version 7.4 (34). Missing data were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) with robust standard errors in Mplus. Structural equation mixture modeling (SEMM) was used to characterize population heterogeneity in the severity and chronicity of AN. SEMM combines features of factor analysis and latent class or latent profile analysis. Similar to latent class or latent profile analysis, SEMM accounts for unknown population heterogeneity; however, observed variables within-class are allowed to vary, and the co-variation is modeled using an underlying continuous factor(s). The advantage of SEMM over other statistical methods is that SEMM allows investigators to directly test whether a particular set of variables that represent a latent construct (in this case, variables we posit reflect SE-AN) fit better as categories, dimensions, or some combination of categories and dimensions. For example, variables representing the construct of height might be modeled as categories (e.g., short versus tall), dimensions (height measured in centimeters), or both (e.g., certain conditions that affect height such as dwarfism or gigantism might be categories, whereas other variability in height might be thought of as dimensional). Given that we were interested in whether differences in severity and chronicity among individuals with AN reflected distinct subgroups or continua, SEMM was the most logical statistical approach for this study.

We tested a series of models, including factor analysis models (i.e., dimensional models), latent profile analysis models (i.e., categorical models), and structural equation factor mixture models (i.e., hybrid dimensional-categorical models). Models included the following indicator variables: 1) self-reported duration of AN; 2) number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms; 3) BMI at admission; 4) objective binge eating episodes; 5) self-induced vomiting; 6) diuretic and laxative misuse; 7) SF-36 role-physical; 8) SF-36 social functioning; and 9) SF-36 emotional well-being. Eating disorder behaviors were dichotomized to represent presence or absence of the behavior. Given that we had a total of nine indicators and three indicators per factor are required for model identification (35), we limited our analysis to testing one- through three- factor exploratory factor analysis solutions. Geomin (oblique) rotation, which is appropriate when factors are correlated, was used for factor analytic models.

Models were estimated with robust maximum likelihood estimation and compared using multiple fit indices, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), sample size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and the consistent Akaike Information Criterion (cAIC). Greater weight was placed on the fit of aBIC because Monte-Carlo simulations have indicated that aBIC has greater accuracy across a range of study designs for identifying correct class membership in latent class analyses (36). Chi-square or MANOVA was used to test whether groups identified through latent profile analysis differed on the following variables: 1) psychiatric comorbidity; 2) relevant demographics (age, employment status, marital status, and education); and 3) eating disorder characteristics (lowest BMI since age 12, DSM-IV AN subtype, EDE subscales, and EDE Global score).

Finally, we conducted analyses to test whether dimensions identified through exploratory factor analysis and groups identified through latent profile analysis predicted clinical outcomes at discharge from treatment. The primary outcome was a categorical rating adapted from the Morgan-Russell criteria (37) and used in our previous research (38). Participants with a “good” outcome had a BMI ≥ 18.5, no episodes of binge-eating or purging during the past 28 days, and an EDE Global score within two standard deviations of community norms (27). Participants with an “intermediate” outcome had a BMI > 17.5 and fewer than four episodes of binge-eating or purging during the past 28 days. Participants with a “poor” outcome had a BMI ≤ 17.5 and/or reported ≥ 4 episodes of binge-eating or purging during the past 28 days. We also examined discharge type (i.e., planned versus against medical advice) as a secondary outcome.

Results

We compared a series of models, including latent profile analysis models ranging from one to three profiles and factor analytic models ranging from one to three factors. Based on a comparison of fit indices within the latent profile and factor analytic models, we ran SEMMs that combined one or three factors with one, two, and three latent profile solutions. Although the three factor-three profile mixture model had the best fit to the data, this model was associated with substantial sparseness for the latent profile solution, such that few participants were classified into LP3 (n=15) due to very extreme scores on latent profile indicators. Of the remaining models, the three factor-two profile mixture model had the best fit to the data (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Model Fit Statistics for Exploratory Factor Analysis, Latent Profile Analysis, and Structural Equation Mixture Models

| Profiles | P | LL | BIC | aBIC | cAIC | AIC | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPA 1c | 15 | −8132.66 | 16353.10 | 16305.52 | 16368.10 | 16295.32 | -- |

| LPA 2c | 25 | −7921.73 | 15989.76 | 15910.45 | 16014.76 | 15893.45 | 0.94 |

| LPA 3c | 35 | −7826.97 | 15858.78 | 15747.74 | 15893.78 | 15723.95 | 0.94 |

|

| |||||||

| Factors | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| FA 1f | 24 | −8008.23 | 16156.91 | 16080.78 | 16180.91 | 16064.46 | -- |

| FA 2f | 32 | −7976.15 | 16139.58 | 16038.06 | 16171.58 | 16016.31 | -- |

| FA 3f | 39 | −7918.81 | 16065.86 | 15942.14 | 16104.86 | 15915.62 | -- |

|

| |||||||

| SEMMs | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1f, 1c | 24 | −8008.41 | 16157.27 | 16081.14 | 16181.27 | 16064.82 | -- |

| 1f, 2c | 26 | −7904.32 | 15960.81 | 15878.32 | 15986.81 | 15860.65 | 0.95 |

| 1f, 3c | 28 | −7836.75 | 15837.36 | 15748.53 | 15865.36 | 15729.50 | 0.95 |

| 3f, 1c | 27 | −7926.07 | 16010.15 | 15924.50 | 16037.15 | 15906.14 | -- |

| 3f, 2c | 31 | −7814.14 | 15809.71 | 15711.36 | 15840.71 | 15690.29 | 0.95 |

| 3f, 3c | 35 | −7726.11 | 15657.05 | 15546.01 | 15692.05 | 15522.22 | 0.96 |

Note. P=parameters; LL=Log-likelihood; BIC=Bayesian Information Criterion; aBIC=Sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion, calculated as −2LL + plog [(N+2)/24]; AIC=Akaike Information Criterion; cAIC=consistent Akaike Information Criterion, calculated as −2LL + p[log(N) + 1]. Smaller values of BIC, aBIC, AIC, and cAIC indicate better data-model fit. “--” was used to indicate that these data are not applicable to the model tested. BIC differences ≥ 6 provide strong evidence favoring the model with the smaller value (43). Higher posterior probabilities and entropy suggest better prediction of latent profile membership and clearer delineation of latent profiles, respectively. Although the three factor-three profile mixture model had the best fit to the data, this model was associated with substantial sparseness for the latent profile analysis, such that few participants were classified into LP3 (n=15) due to very extreme scores on latent profile indicators.

Latent Factors (Dimensions)

Table 3 presents factor loadings for the best-fitting exploratory factor analysis model. As shown, Factor 1 included binge eating, self-induced vomiting, and laxative or diuretic misuse; Factor 2 comprised the SF-36 quality-of-life domains; and Factor 3 was characterized by illness duration, number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms, and BMI at admission.

Table 3.

Best-fitting exploratory factor analysis model

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective binge eating episodes | 1.00* | .01 | −.05 |

| Self-induced vomiting | .83* | −.11 | .02 |

| Laxative and diuretic misuse | .28* | −.25* | −.01 |

| Duration of illness | .01 | −.12 | .65* |

| Number of hospital admissions | −.08 | .02 | .60* |

| Body mass index at admission | .14 | .01 | −.28* |

| SF-36 role-physical | .09 | .74* | .00 |

| SF-36 emotional well-being | −.04 | .67* | −.04 |

| SF-36 social functioning | .00 | .72* | .06 |

Note. Lower body mass index and lower scores on the SF-36 domains indicate greater clinical severity; for all other variables, higher scores delineate greater severity. Significant factor loadings are in bold;

p<.05;

Unstandardized oblique factor loadings are reported because Mplus does not provide standardized factor loadings for exploratory factor analyses. The factor loading was greater than 1.00 for objective binge eating (note the factor loading was 1.001) due to reporting un-standardized loadings. Because factor loadings > 1.00 can be associated with Heywood Cases (negative residual variances associated with model over-fitting), we re-ran this analysis using SPSS, which provided standardized factor loadings, and did not find factor loadings greater than 1.00 (for the un-rotated and promax-rotated solutions). We also did not find negative residual variances that were significantly different from zero for any variables in the original Mplus analysis. We chose to report un-standardized factor loadings from Mplus (versus standardized factor loadings from SPSS) to provide consistent results across the latent profile, factor analytic, and mixture models.

We ran a full-information maximum likelihood structural equation model (SEM) with robust weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) to test the fit of the model identified through exploratory factor analysis to the observed data, and determine whether latent factors predicted clinical outcomes. Results indicated that the dimensional three-factor model had a good fit to the data (χ2[36] = 58.09, p < 0.02; RMSEA = 0.045; CFI = 0.953; TLI = 0.929). Moreover, all three latent factors predicted clinical outcomes at discharge from treatment (p’s < 0.005). Specifically, scores on Factor 1 and Factor 3 were negatively correlated with outcome ratings (λ = −0.22 and −0.27, respectively), indicating that greater severity on these dimensions was associated with poorer clinical outcomes at treatment discharge. In contrast, scores on Factor 2 were positively correlated with clinical outcome ratings, suggesting that patients with better health-related quality-of-life had more favorable clinical outcomes at the end of treatment (λ = 0.22). There was no association between latent factors and discharge type (p’s > 0.40).

Latent Profiles (Categories)

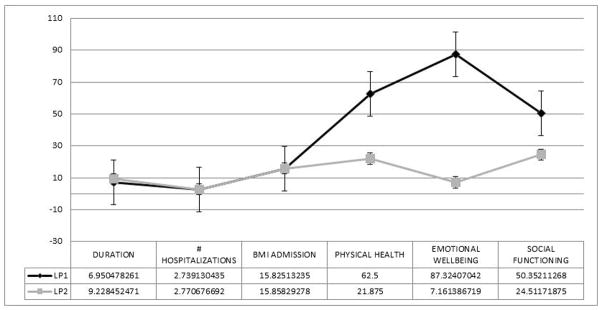

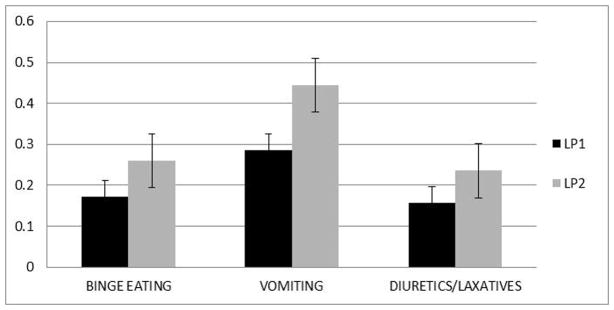

The two profiles were a lower severity group (LP1; n=71) and a higher severity group (LP2; n=277) (see Figures 1 and 2). Profiles were equivalent on illness duration, number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms, and BMI at admission. However, LP2 had more eating disorder behaviors and poorer quality-of-life (see Figures 1 and 2). Entropy for the three factor-two profile mixture model was 0.95, and mean posterior probabilities of class membership (which provide a profile-specific measure of how well indicator variables predict latent class membership) were excellent, ranging from 0.98 for LP2 to 0.99 for LP1.

Figure 1. Mean item responses for clinical and psychosocial/health indicators for the best-fitting latent profile analysis.

LP1=Latent profile 1; LP2=Latent profile 2; Duration=Duration of illness; BMI=Body mass index; Lower scores on BMI at admission, physical health, emotional well-being, and social functioning are associated with worse functioning, whereas for all other variables higher scores are associated with greater severity. Error bars represent the standard error.

Figure 2. Mean item responses for eating disorder behaviors for the best-fitting latent profile analysis.

Error bars represent the standard error.

Compared to LP1, participants in LP2 were significantly older (Mean [SE] = 26.90 [0.63] years vs. 23.15 [1.21] years, p < 0.007), had higher scores on the EDE Weight Concern subscale (Mean [SE] = 3.51 [0.12] vs. 2.93 [0.23], p < 0.03), and were more likely to have a lifetime mood disorder (62.1% vs. 38.1%, χ2 [1] = 11.62, p < 0.002) and a lifetime anxiety disorder (48.5% vs. 33.3%, χ2 [1] =4.59, p < 0.04). Latent profiles did not differ with respect to DSM-IV AN subtype (i.e., restricting vs. binge-eating/purging, p > 0.16), frequency of lifetime substance use disorders (p > 0.06), lowest BMI since age 12 (p > 0.24), EDE Eating Concern (p > 0.06), EDE Shape Concern (p > 0.28), EDE Restraint (p > 0.36), or EDE Global score (p > 0.08). Groups also did not differ on proportion of individuals with at least some college education (p > 0.08), percent unemployed (p > 0.10), and percent never married (p > 0.17). Finally, there were no differences between LP1 and LP2 with respect to clinical outcome at discharge from treatment (p > 0.19) or rates of discharge against medical advice (p > 0.55). 1

Discussion

Targeted approaches for the treatment of SE-AN have been recommended (1), but there is no consensus definition of severe and enduring eating disorder psychopathology to inform research and clinical practice (2, 3). This study is important as the first effort to utilize empirical methods to characterize associations among putative indicators of severity and chronicity in eating disorders, with the goal of developing an evidence-based definition of SE-AN. Results suggest that patients with AN can be classified on the basis of eating disorder behaviors (i.e., binge eating and purging) and impairment in health-related quality-of-life, but we found no evidence for a chronic subgroup of AN. Instead, indices of chronicity (i.e., illness duration, refractoriness to inpatient treatment, and low BMI) varied dimensionally within each latent profile. These findings and their implications are discussed below.

The best-fitting model in the current study included two categories and three dimensions. Specifically, we found that patients with AN could be grouped into higher and lower severity profiles that differed with respect to eating disorder behaviors and quality-of-life, as well as several external validators including age, weight concerns, and lifetime mood and anxiety comorbidity. Moreover, within each severity profile there was dimensional variability in eating disorder behavior, quality-of-life, and indicators of chronicity (i.e., illness duration, repeated bouts of hospital treatment, and low BMI). This hybrid model accounts for categorical distinctions between patients, while recognizing within-group heterogeneity in severity and chronicity. For example, two patients classified into the higher severity profile might differ from one another in number of eating disorder behaviors, degree of quality-of-life-impairment, or years of illness while sharing a categorical distinction from patients classified into the lower severity profile. Importantly, scores on the latent factors (i.e., dimensions) predicted clinical outcome at discharge from intensive treatment, whereas there was no association between profile membership and clinical outcomes. These findings highlight the complexity of SE-AN and the importance of considering multiple facets of severity and chronicity in research and clinical practice.

It is noteworthy that indicators linked most closely to the ‘enduring’ aspect of SE-AN, namely illness duration and number of hospitalizations for eating disorder symptoms (an index of treatment resistance), did not differentiate subgroups in the current sample. Rather, our findings suggested that these characteristics vary continuously among individuals with AN. This contrasts with previous research, which has relied almost exclusively on illness duration to distinguish SE-AN from earlier stage AN presentations (1, 6–10). Although our findings suggest that a dimensional approach represents the nature of chronicity in AN more accurately than a categorical model, this does not necessarily mean that a clinically significant threshold for chronicity could not be identified. For instance, some scholars have advocated the use of statistical techniques based on signal detection theory (SDT) to select optimal cutoff scores for psychological assessments (39). In an SDT analysis, the cutoff for differentiating between chronic and acute AN would be calculated as a function of the desired hit (true positives) and false alarm (false positive) rates, as well as the prevalence of chronic AN in a given population. These methods have been used in other areas of medicine to evaluate the utility of clinical tests for differentiating between diagnostic groups (39) and represent a promising direction for future research.

This study extends prior research by documenting that impairment in quality-of-life differentiates severity profiles in AN. Poor quality-of-life has been proposed as an indicator of chronicity in eating disorders (2), and treatments designed for SE-AN have emphasized quality-of-life as a primary clinical outcome (1). The current findings support these approaches and suggest that routine assessment of quality-of-life could help to improve the clinical utility of AN diagnoses. In particular, our data imply that there may be a subgroup of individuals with AN for whom impairment in health-related quality-of-life is especially pronounced.

Consistent with previous research (40), eating disorder behaviors distinguished subgroups of AN. Moreover, our finding that eating disorder behaviors varied dimensionally within the AN severity profiles aligns with the results of another SEMM study, which found that number of eating disorder symptoms served as a dimensional index of severity across bulimia spectrum diagnoses (13). However, in contrast to Keel et al. (13), BMI did not contribute to the eating disorder behavior dimension in the current study. Rather, low BMI loaded with more traditional indices of chronicity in eating disorders (i.e., longer illness duration and refractoriness to inpatient treatment) suggesting that it may be an index of enduring AN.

The use of empirical methods to characterize associations among multiple indicators of severity and chronicity in eating disorders is an important strength of this study, given that most research on SE-AN has focused exclusively on illness duration. Nevertheless, several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, participants were receiving inpatient or partial hospital treatment at academic medical center eating disorders programs and may not be representative of individuals with AN in the community. This said, data presented in Table 1 show that a significant minority of the current sample was severely underweight (i.e., BMI < 14) and had been ill for at least 10 years, suggesting that we were successful in recruiting individuals with severe and enduring AN. Second, individuals in ethnic/racial minority groups and men were underrepresented, consistent with demographic data on service utilization in eating disorders (41). Third, because this study focused solely on individuals with AN, we cannot comment on characteristics that might contribute to the classification of severe and enduring eating disorders more broadly. Fourth, post-treatment follow-up data were available only for participants recruited at the Pittsburgh site; consequently, we did not have sufficient statistical power to test whether the categories and dimensions identified in this study predicted clinical outcomes following discharge from treatment. Nevertheless, the current findings suggest that dimensional indices of SE-AN have utility for predicting initial response to inpatient or partial hospital care. Finally, as is the case for any empirical classification study, our results reflect the indicators included in our model. It is possible that variables we did not consider might contribute to the classification of SE-AN.

In closing, this study provides the first empirical evidence for the structure of severity and chronicity in AN. Results suggest that chronicity varies continuously among patients with AN, whereas severity, as defined by eating disorder behaviors and quality-of-life, varies both continuously and categorically. The current findings are an important initial step toward our goal of developing an evidence-based definition of SE-AN, but additional research is needed. In particular, studies to test whether the current model replicates in independent samples, especially community-based samples and samples that include a full range of eating disorder psychopathology, are needed. In addition, research using different statistical methods (e.g., SDT analyses) and alternative indicators and validators is needed to elucidate whether thresholds for defining an ‘enduring’ class of AN can be identified. For example, a staging model of eating disorders has been described in which severe and enduring presentations are characterized by neuro-progressive changes that were not evaluated in the current study (42). If the inclusion of different indicators helped to distinguish SE-AN from more acute presentations, this might suggest criteria for an evidence-based definition. Research comparing the predictive validity of various models of SE-AN (e.g., empirically based versus theoretically driven) also is needed to develop an evidence-based definition.

At a conceptual level, it is important to acknowledge limitations inherent in the construct ‘SE-AN’. In particular, severity and enduringness are dimensional concepts. Although it may be possible to ‘carve nature at its joints’ in a way that has utility for clinicians and investigators in the field, patients can present at any point along each of these continua. Thus, aspects of a SE-AN definition (e.g., illness duration) may need to be conceptualized dimensionally. Furthermore, severity and enduringness are not necessarily correlated in AN. There are enduring, but mild forms of the illness (e.g., a person who maintains a BMI of 17.0 for 20+ years through dietary restriction and moderate exercise, but has no significant medical problems or psychosocial impairment). Likewise, there are severe, but shorter-term AN presentations (e.g., a teenager with symptom onset in the last year who presents with a BMI of 13.0 and serious medical complications secondary to purging). Thus, when we use the term SE-AN, it must be with an awareness of these other groups and the complicated nature of the constructs we are studying.

From a clinical perspective, our findings underscore the importance of a holistic approach to the assessment of severity and chronicity in eating disorders. Although factors like illness duration and repeated treatment failures play a role in explaining heterogeneity in AN, other variables that might be overlooked in routine practice also should be considered. In particular, our findings highlight the importance of quality-of-life in distinguishing subgroups of AN.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements/Disclosure of Conflicts

Research supported, in part, by National Institute of Mental Health grants K01MH080020 and T32MH096679.

Dr. Attia receives research support from Eli Lilly & Co. The other authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

To test whether sample recruitment source influenced validation analysis results, we re-ran the MANOVA with recruitment source entered as a covariate. Results were largely unchanged as a result of controlling for recruitment site, with the exception that lifetime presence of any substance use disorder was significantly greater for participants in LP2 and EDE Weight Concern no longer differed significantly between groups (data available upon request).

References

- 1.Touyz S, Le Grange D, Lacey H, Hay P, Smith R, Maguire S, et al. Treating severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2501–2511. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Myers TC, Kadlec K, LaHaise K, et al. Minimizing and treating chronicity in the eating disorders: A clinical overview. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:467–475. doi: 10.1002/eat.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hay P, Touyz S. Treatment of patients with severe and enduring eating disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:473–477. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson HJ, Bulik CM. Update on the treatment of anorexia nervosa: Review of clinical trials, practice guidelines and emerging interventions. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2477–2500. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712002620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strober M. Managing the chronic, treatment-resistant patient with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36:245–255. doi: 10.1002/eat.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arkell J, Robinson P. A pilot case series using qualitative and quantitative methods: Biological, psychological and social outcome in severe and enduring eating disorder (anorexia nervosa) Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:650–656. doi: 10.1002/eat.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bamford BH, Mountford VA. Cognitive behavioural therapy for individuals with longstanding anorexia nervosa: Adaptations, clinician survival and system issues. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20:49–59. doi: 10.1002/erv.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox JR, Diab P. An exploration of the perceptions and experiences of living with chronic anorexia nervosa while an inpatient on an eating disorders unit: An interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) study. J Health Psychol. 2015;20:27–36. doi: 10.1177/1359105313497526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dawson L, Rhodes P, Touyz S. “Doing the impossible”: The process of recovery from chronic anorexia nervosa. Qual Health Res. 2014;24:494–505. doi: 10.1177/1049732314524029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andries A, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A, Stoving RK. Dronabinol in severe, enduring anorexia nervosa: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:18–23. doi: 10.1002/eat.22173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tierney S, Fox JR. Chronic anorexia nervosa: A Delphi study to explore practitioners’ views. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:62–67. doi: 10.1002/eat.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguire S, Touyz S, Surgenor L, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Lacey H, et al. The clinician administered staging instrument for anorexia nervosa: Development and psychometric properties. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:390–399. doi: 10.1002/eat.20951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keel PK, Crosby RD, Hildebrandt TB, Haedt-Matt AA, Gravener JA. Evaluating new severity dimensions in the DSM-5 for bulimic syndromes using mixture modeling. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:108–118. doi: 10.1002/eat.22050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubke GH, Muthen B. Investigating population heterogeneity with factor mixture models. Psychol Methods. 2005;10:21–39. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.10.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway C, Hammen C, Brennan P. A comparison of latent class, latent trait, and factor mixture models of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a community setting: Implications for DSM-5. J Pers Disord. 2012;26:793–803. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frazier TW, Youngstrom EA, Speer L, Embacher R, Law P, Constantino J, et al. Validation of proposed DSM-5 criteria for autism spectrum disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:28–40. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Legrand LN, Iacono WG, McGue M. Are the symptoms of cannabis use disorder best accounted for by dimensional, categorical, or factor mixture models? A comparison of male and female young adults. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:68–77. doi: 10.1037/a0026230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubke GH, Muthen B, Moilanen IK, McGough JJ, Loo SK, Swanson JM, et al. Subtypes versus severity differences in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the Northern Finnish Birth Cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1584–1593. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815750dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McBride O, Teesson M, Baillie A, Slade T. Assessing the dimensionality of lifetime DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and a quantity-frequency alcohol use criterion in the Australian population: A factor mixture modelling approach. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:333–341. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muthen B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allan NP, Raines AM, Capron DW, Norr AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Identification of anxiety sensitivity classes and clinical cut-scores in a sample of adult smokers: Results from a factor mixture model. J Anxiety Disord. 2014;28:696–703. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildes JE, Forbush KT, Markon KE. Characteristics and stability of empirically derived anorexia nervosa subtypes: Towards the identification of homogeneous low-weight eating disorder phenotypes. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:1031–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0034676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Becker AE, Thomas JJ, Pike KM. Should non-fat-phobic anorexia nervosa be included in DSM-V? Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:620–635. doi: 10.1002/eat.20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders - Patient Edition (With Psychotic Screen) (SCID-I/P (W/PSYCHOTIC SCREEN) New York: Biometrics Research Department; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User’s Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders - Research Version - (SCID-I for DSM-IV-TR, November 2002 Revision) New York: Biometrics Research Department; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor ME. Eating Disorder Examination (Edition 16.0D) In: Fairburn CG, editor. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 265–308. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchison D, Hay P, Engel S, Crosby R, Le Grange D, Lacey H, et al. Assessment of quality of life in people with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A comparison of generic and specific instruments. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:284. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén;; 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding L, Velicer WF, Harlow LL. Effects of estimation methods, number of indicators per factor, and improper solutions on structural equation modeling fit indices. Struct Equ Modeling. 1995;2:119–143. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swanson SA, Lindenberg K, Bauer S, Crosby RD. A Monte Carlo investigation of factors influencing latent class analysis: An application to eating disorder research. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:677–684. doi: 10.1002/eat.20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan HG, Russell GF. Value of family background and clinical features as predictors of long-term outcome in anorexia nervosa: Four-year follow-up study of 41 patients. Psychol Med. 1975;5:355–371. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700056981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wildes JE, Marcus MD, Crosby RD, Ringham RM, Dapelo MM, Gaskill JA, et al. The clinical utility of personality subtypes in patients with anorexia nervosa. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:665–674. doi: 10.1037/a0024597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McFall RM, Treat TA. Quantifying the information value of clinical assessments with signal detection theory. Annu Rev Psychol. 1999;50:215–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keel PK, Brown TA, Holland LA, Bodell LP. Empirical classification of eating disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:381–404. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marques L, Alegria M, Becker AE, Chen CN, Fang A, Chosak A, et al. Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across US ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2011;44:412–420. doi: 10.1002/eat.20787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treasure J, Cardi V, Leppanen J, Turton R. New treatment approaches for severe and enduring eating disorders. Physiol Behav. 2015;152(Pt B):456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raftery AE. Bayes factors and BIC. Sociol Methods Res. 1999;27:411–417. [Google Scholar]