Abstract

Aim

The p.P301L mutation in microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) is a common cause of frontotemporal dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17). We compare clinicopathologic features of five unrelated and three related (brother, sister and cousin) patients with FTDP-17 due to p.P301L mutation.

Methods

Genealogical, clinical, neuropathologic, and genetic data were reviewed from eight individuals.

Results

The series consisted of five men and three women with an average age of death of 58 years (52–65 years) and average disease duration of 9 years (3–14 years). The first symptoms were those of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia in seven patients and semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia in one. Three patients were homozygous for the MAPT H1 haplotype; five had H1/H2 genotype. The apolipoprotein E genotype was ε3/ε3 in seven and ε3/ε4 in one. The average brain weight was 1015 grams (876 – 1188 grams). All had frontotemporal lobar or more diffuse cortical atrophy. Except for one patient, the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus had minimal atrophy, while there was atrophy of middle and inferior temporal gyri. Dentate fascia neuronal dispersion was identified in three patients, two of whom had epilepsy. In one patient there was extensive white matter tau involvement with Gallyas-positive globular glial inclusions typical of globular glial tauopathy (GGT).

Conclusions

This clinicopathologic study shows inter- and intra-familial clinicopathologic heterogeneity of FTDP-17 due to MAPT p.P301L mutation, including GGT in one patient.

Keywords: MAPT, hereditary tauopathies, FTDP-17, GGT, FTLD

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17T (FTDP-17) is an umbrella term for hereditary tauopathies caused by mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) at chromosome 17q21.3 [1]. Of 14 MAPT exons, alternative splicing of exon 10 results in two functionally distinct isoforms that have either three or four 31-amino acid repeats depending on whether exon 10 is excluded (3R tau) or included (4R tau) [2]. To date more than 50 mutations in exons 1, 9–13 and introns 9 and 10 have been reported in about 200 families (see http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations) [3]. The p.P301L mutation in exon 10 is one of the most common [3]. The pathogenetic effect of this mutation includes reduced ability of mutated 4R tau to bind to microtubules and promote microtubule assembly [4], as well as enhanced in vitro heparin-induced assembly into pathological tau filaments [5].

FTDP-17 follows a pattern of autosomal dominant inheritance with clinical, biochemical and neuropathologic heterogeneity [3]. The phenotypes overlap with phenotypes of sporadic primary tauopathies, including progressive supranuclear palsy [6], Pick’s disease (PiD) [7], corticobasal degeneration (CBD) [8] and globular glial tauopathy (GGT) [9].

GGT is a newly recognized 4R tauopathy with extensive white matter tau pathology and characteristic glial inclusions, including Gallyas-positive globular oligodendroglial inclusions (GOI) and globular astrocytic inclusions (GAI). The latter are usually Gallyas-negative or at most show only weak staining with Gallyas silver method [10]. A proposed classification of GGT includes three clinicopathologic subtypes: subtype I with frontotemporal distribution of tau pathology and clinical features of frontotemporal dementia (“FTD-type”); subtype II with pyramidal features from motor cortex involvement and corticospinal tract degeneration (“motor neuron disease (MND)-type”); and subtype III with a combination of FTD and MND (“FTD & MND-type”) [10].

Here, we compare and contrast clinicopathologic features of five unrelated and three related patients with FTDP-17 due to p.P301L mutation, including one patient with a GGT phenotype.

Material and Methods

Subjects and samples

Brains from four unrelated patients with FTDP-17 due to p.P301L mutation were acquired from the brain bank for neurodegenerative disorders at Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville. Brains from the remaining patient and from three individuals of an affected family were acquired from the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester. All brains were collected between 2006 and 2012. Autopsies were performed after approval by the next-of-kin. All samples were received after informed consent according to protocols approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Genetic, genealogical, clinical and laboratory investigations

Genealogical, clinical and laboratory information was collected by medical chart review. TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assays were used to determine the MAPT H1/H2 haplotype (rs1052553) and the apolipoprotein-E (APOE) genotype (rs429358 and rs7412) following the manufacturer's instructions. Genotype data was analyzed on the QuantSudio 7 Flex Real-Time PCR system software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Tissue sampling and neuropathologic assessment

The brains of Patients 1 and 2 were divided in the midsagittal plane with the right hemibrains fixed in 10% formalin and the left half frozen at −80°C. The left hemisphere was fixed and the right hemisphere was frozen in the remaining six patients. All patients underwent standard methodological procedures for tauopathies. Formalin-fixed tissue was sampled with a standardized dissection and sampling method and embedded in paraffin blocks. The sampled regions included frontal, temporal, parietal, motor, visual and cingulate cortices, amygdala, hippocampus (two levels), nucleus accumbens, lentiform nucleus, thalamus at level of subthalamic nucleus, mesencephalon, pontomesencephalic junction, rostral pons, medulla oblongata, and two sections of cerebellum including vermis and deep nuclei.

Sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin were used for histologic evaluations of neuronal loss and gliosis. Alzheimer-type pathology was assessed with thioflavin-S fluorescent microscopy. Tract degeneration and white matter changes were assessed with Luxol fast blue for myelin and ionizing binding adapter protein 1 immunohistochemistry.

Tau immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed using a DAKO Autostainer (Universal Staining System, Carpinteria, CA, USA). Sections from paraffin embedded tissue were cut at a thickness of 5 microns and allowed to dry overnight in a 60 degree oven. Following deparaffinization and rehydration, antigen retrieval was performed by steaming the sections for 30 minutes in deionized water. For 3R tau and 4R tau antibodies, prior to steaming, tissue sections were incubated for 30 minutes in 98% formic acid. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked for 5 minutes with 0.03% hydrogen peroxide. Sections were then treated with 5% normal goat serum for 20 minutes. Subsequently, sections were incubated for 45 minutes at room temperature in the following antibodies: mouse monoclonal phospho-tau (CP13- phospho-serine 202; mouse IgG1, 1:1,000, gift form Peter Davies, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health Care System), 3R tau- and 4R tau antibody (RD3, RD4; 1:5000, Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA). After primary antibody incubation, sections were incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in Envision-Plus mouse or rabbit labeled polymer HRP (DAKO Autostainer). Peroxidase labeling was visualized with the chromogen solution 3, 3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB-Plus). The sections were then counterstained with Lerner 1 hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific) and coverslipped with Cytoseal mounting medium (Thermo Scientific).

In addition, Gallyas silver stain was used to assess argyrophilia of globular inclusions in Patient 1.

Results

Clinical, genealogical, genetic and neuropathologic data of all eight patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Anatomic distribution and severity of tau pathology is summarized in Table 3. In all eight patients the MAPT p.P301L (c.902C>T NM_005910) mutation was identified. No deoxyribonucleic acid was available from the relatives of Patients 1–5 to determine segregation pattern of the p.P301L mutation.

Table 1.

Clinical, genealogical and genetic data of eight patients with MAPT p.P301L mutation

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | F | M | M | M | F | F | M | M |

| Age of death (y) | 65 | 53 | 62 | 52 | 64 | 61 | 55 | 56 |

| Duration (y) | 12 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 5 | 14 |

| Initial presentation | personality/ behavior changes,short-term memory loss |

personality/ behavior changes, bradykinesia, hand tremor |

personality/ behavior changes |

personality/ behavior changes |

personality/behavi or changes |

personality/behavi or changes, mild cognitive impairment |

personality/behavi or changes |

short time memory loss, anomia |

| FTD type* | bvFTD | bvFTD | bvFTD | bvFTD | bvFTD | bvFTD | bvFTD | svPPA |

| Parkinsonism | bradykinesia, rigidity, hand tremor, postural instability, gait freezing, hypomimia |

rigidity, hand tremor, unsteady gait |

bradykinesia, unsteady gait, stooped posture |

none | arm rigidity, bradykinesia, reduced arm swing, hypomimia |

mild rigidity in upper limbs |

shuffling gait, multiple falls |

rigidity of right upper limb, hypomimia |

| Distribution of motor signs |

L > R | N/A | N/A | none | R > L | R = L | N/A | R>L |

| Other signs & symptoms |

long-term memory loss, dysphagia, secondary semantic dysfunction, dyscalculia, incontinence |

hallucinations, memory impairment, hyperphagia, incontinence |

paratonia, apraxia, epilepsy, secondary semantic dysfunction, incontinence |

mild cognitive decline |

secondary semantic dysfunction, reduced empathy, incontinence |

bilateral palmomental reflex, immobile, nonverbal (end stage) |

secondary semantic dysfunction |

poor hygiene, angry outbursts, food fads, epilepsy |

| Brain imaging | MRI (57y): ventriculo megaly; PET (54y): normal |

MRI (atrophy, no further details) |

MRI (60y): ventriculo- megaly, fronto- temporal atrophy; SPECT (60y): fronto- parietal & temporal hypoperfusion |

MRI (48y): frontotemporal atrophy L>R; PET (48y): frontotemporal hypometa- bolism |

MRI (60y): frontotemporal atrophy L> R, esp. L anterior temporal & hippocampal atrophy |

SPECT (55y): frontotemporal hypoperfusion; MRI (56y): frontotemporal atrophy R> L |

MRI (55y): moderate frontal & temporal atrophy, mild hippocampal atrophy |

MRI (49y): frontotemporal atrophy, left middle & anterior temporal |

| Family history of early onset dementia |

mother, maternal grandmother |

mother, several maternal aunts & uncles, cousin |

6 of 11 siblings, mother & maternal aunt |

mother, maternal grandfather & aunt |

father | father, 2 brothers, 2 paternal aunts, 3 cousins |

brother, sister, mother, maternal aunts, cousins |

father, brother, sister, 2 paternal aunts, 3 cousins |

| MAPT | H1/H1 | H1/H1 | H1/H2 | H1/H2 | H1/H2 | H1/H1 | H1/H2 | H1/H2 |

| APOE | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε4 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε3 |

Abbreviations.

defined on the basis of leading features at the initial clinical presentation;

APOE = apolipoprotein E gene; bvFTD = behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia; ε = epsilon (APOE allele); FTD = frontotemporal dementia; L = left; MAPT = microtubule-associated protein tau gene; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; N/A = not available; PET (FDG-PET) = fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography; R = right; SPECT (99mTc-HMPAO SPECT) = technetium hexamethylpropylene amine oxime single-photon emission computed tomography; svPPA = semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia; y = years (old)

Table 2.

Neuropathologic features of eight patients with MAPT p.P301L mutation

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | Patient 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain weight (g) | 880 | 1080 | 1050 | 1000 | 1040 | 880 | 1190 | 1010 |

| Braak stage | 0 | 0 | II | 0 | III | II | 0 | 0 |

| Cortical atrophy | lobar: severe frontal; mild temporal and parietal |

lobar: severe frontal and temporal |

lobar: severe frontal; mild to moderate temporal |

lobar: severe frontal; moderate temporal |

lobar: severe frontal and temporal |

lobar: severe frontal and temporal; mild parietal |

lobar: mild temporal and frontal |

global: severe frontal, temp- oral, parietal and occipital |

| Atrophy of middle and inferior temporal gyri |

mild | mild to moderate |

moderate to severe |

moderate | severe | severe | moderate to severe |

very severe |

| Hippocampal atrophy | none | none | severe | none | mild | mild | mild | none |

| Subthalamic neuron loss | severe | moderate | none | severe | none | N/A | none | none |

| Substantia nigra neuron loss | severe | severe | moderate | moderate | severe | severe | moderate | severe |

| Cerebral tau pathology | white matter ≤ gray matter |

gray matter > white matter |

gray matter > white matte |

gray matter > white matte |

white matter ≤ gray matter |

gray matter > white matter |

gray matter > white matte |

gray matter > white matter |

| Glial tau pathology | frequent GOI & GAI;rare CB |

frequent GFA; rare CB |

frequent GFA; rare CB |

sparse GFA; sparse CB |

frequent TA & GFA; rare CB |

sparse GFA; sparse CB |

sparse GFA; rare CB |

sparse GFA sparse CB |

| Other features | moderate CN atrophy; BN |

moderate CN atrophy; BN |

mild CN atrophy |

severe CN & thalamic atrophy; BN |

severe CN atrophy; BN |

severe CN atrophy; BN |

severe CN atrophy |

severe CN atrophy |

| Diagnosis | FTDP-17 (GGT) |

FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 | FTDP-17 |

Abbreviations. 3R = three repeat tau isoform; 4R = four repeat tau isoform; BN = ballooned neurons; CB = coiled bodies; GGT = globular glial tauopathy; CN = caudate nucleus; FTDP-17 = frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17; GAI = globular astrocytic inclusions; GFA = granular/fuzzy astrocytes; GOI = globular oligodendroglial inclusions; N/A = not available; TA = tufted astrocytes

Table 3.

Severity and anatomical distribution of neuronal and glial tau pathology in eight patients with MAPT p.P301L mutation

| Region | Tau (+) neurons | Tau (+) oligodendrocytes | Tau (+) astrocytes | Tau (+) threads | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Temporal cortex | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Mid frontal | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Striatum | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Globus pallidus | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ⋯ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | … |

| Basal nucleus | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ⋯ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | … |

| Hypothalamus | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | … | … |

| Thalamus | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ⋯ | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ⋯ | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | … | 3 | 3 |

| Subthalamic nucleus | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | ⋯ | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | … | … | 3 |

| Red nucleus | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Substantia nigra | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Midbrain tectum | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ⋯ | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | … | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | … | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Locus ceruleus | 2 | 3 | ⋯ | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | … | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | … | 3 | 3 | … | … | 3 | 3 | 2 | … |

| Pontine tegmentum | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ⋯ | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | … | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | … |

| Pontine base | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | … | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | … |

| Medullary tegmentum | ⋯ | 2 | 2 | 2 | ⋯ | 2 | 1 | ⋯ | … | 0 | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | 0 | 0 | ⋯ | … | 0 | 1 | 0 | … | 0 | 0 | … | … | 2 | 1 | 2 | … | 3 | 2 | … |

Abbreviations. 0 = negative; 1 = occasional; 2 = moderate numbers; 3 = frequent numbers; … = not available; IHC = tau immunohistochemistry; NFT = neurofibrillary tangles; pre-NFT = pre-tangles. Patient 1 with the GGT phenotype

Patient 1

Clinical and laboratory findings

Patient 1 was a 65-year-old right-handed white woman who at the age of 53 years noticed changes in personality and behavior consistent with behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD). This was followed by slow decline in her short-term memory. During the subsequent four years, she developed parkinsonian features such as bradykinesia, shuffling gait, symmetric rigidity, stooped posture, intermittent mild rest hand tremor, and hypomimia. Initial responsiveness to dopaminergic therapy and fluctuations of cognitive skills led to a tentative diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed moderate ventriculomegaly and fludeoxyglucose (FDG) brain positron emission tomography (PET) scan was normal in the early stage of the disease. As the disease progressed, she exhibited language difficulties, with impaired comprehension and dysnomia but fluent speech, consistent with secondary semantic dysfunction that later evolved to mutism. The family reported episodes of compulsive gambling, urinary incontinence and marked postural instability with backward falls. In the end-stage of the disease, she was wheelchair-bound, and she developed bilateral spastic contractures of her distal joints, worse on the left, which were treated with injections of botulinum toxin A to a moderate effect. Trials of dopaminergic (carbidopa/levodopa), antipsychotic (quetiapine, risperidone) and anti-dementia (rivastigmine) drugs as well as antioxidants (vitamins C, E, coenzyme Q), lorazepam were unsuccessful in the long-term.

The patient’s maternal grandmother and mother were clinically diagnosed with early-onset personality changes and dementia. The patient’s mother died at 58 years of age. The patient’s brother had no history of neurological disease. Genetic studies revealed homozygosity for MAPT H1 haplotype. Her APOE genotype was ε3/ε3.

Neuropathologic findings

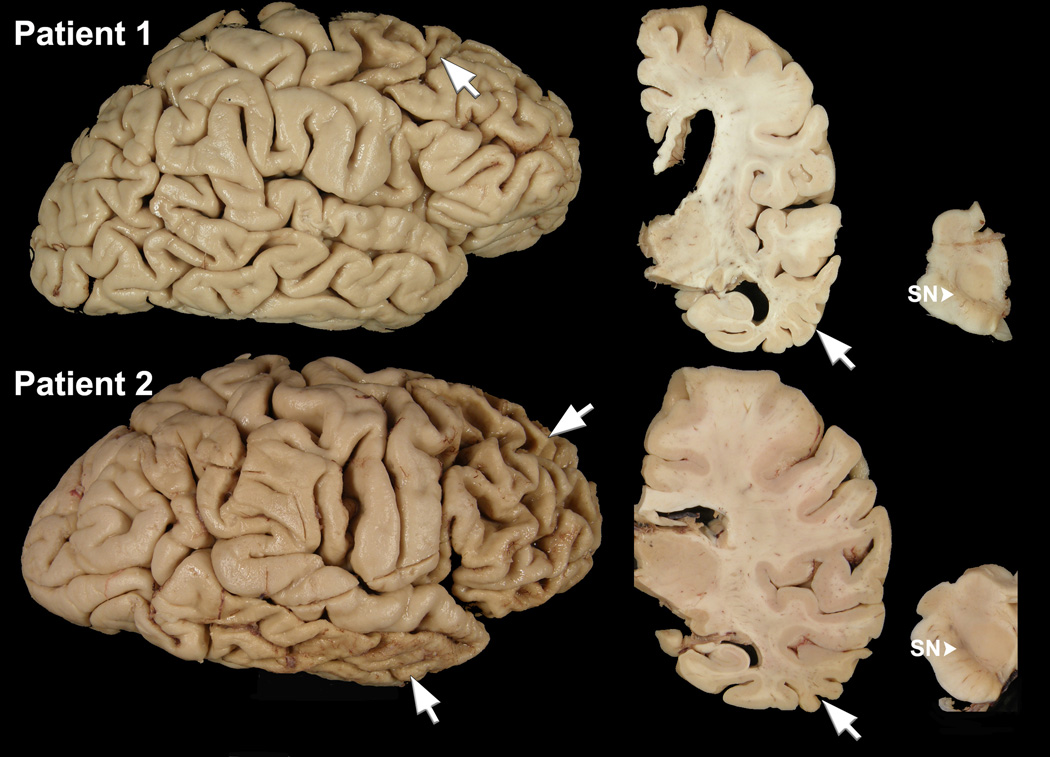

The calculated brain weight was 880 grams. There was cortical atrophy of the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, most marked in the superior frontal gyrus (Figure 1). The subjacent cerebral white matter showed tan discoloration and softening. There was moderate enlargement of the lateral ventricles, especially of the frontal horn, and moderate atrophy of the caudate nucleus. The hippocampal formation and amygdala were free of atrophy, but the middle and inferior temporal gyri had atrophy (Figure 1). The substantia nigra had decreased pigmentation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Macroscopic findings of Patient 1 who has GGT type microscopic pathology (top row). Lateral cerebral hemisphere view shows focal cortical affects most marked in the superior frontal gyrus (arrow). A coronal section at level of the lateral geniculate nucleus shows enlargement of frontal more than temporal horn of the lateral ventricle, atrophy of middle and inferior temporal gyri (arrow), but minimal atrophy of the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. A transverse section of midbrain shows marked decreased neuromelanin pigmentation of the substantia nigra (SN, arrowhead). Macroscopic findings of a more typical of FTDP-17 patient (Patient 2; bottom row). The lateral cerebral hemisphere shows severe (“knife-edge”) atrophy of the frontal lobe (arrow) and the inferior temporal lobe (arrow), with sparing of peri-Rolandic cortices and the posterior part of the superior temporal gyrus. A coronal section at level of the lateral geniculate nucleus shows atrophy of middle and inferior temporal gyri (arrow), but minimal atrophy of the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. A transverse section of midbrain shows moderately decreased neuromelanin pigmentation of the substantia nigra (SN, arrowhead).

Sections from frontal, temporal and parietal lobes, and to a lesser extent from the peri-Rolandic primary cortices, showed neuronal loss and gliosis as well as many ballooned neurons. The white matter was pale, vacuolated, gliotic and depleted of myelinated fibers in a distribution corresponding with the areas with the most severe cortical atrophy. Neither significant neuronal loss nor gliosis were seen in the hippocampus. There was subtle gliosis in the caudate nucleus. The subthalamic nucleus had severe neuronal loss and fibrillary astrogliosis. There was marked neuronal loss with extraneuronal neuromelanin, but no Lewy bodies, in the substantia nigra. No Alzheimer-type changes were appreciated with thioflavin-S fluorescent microscopy.

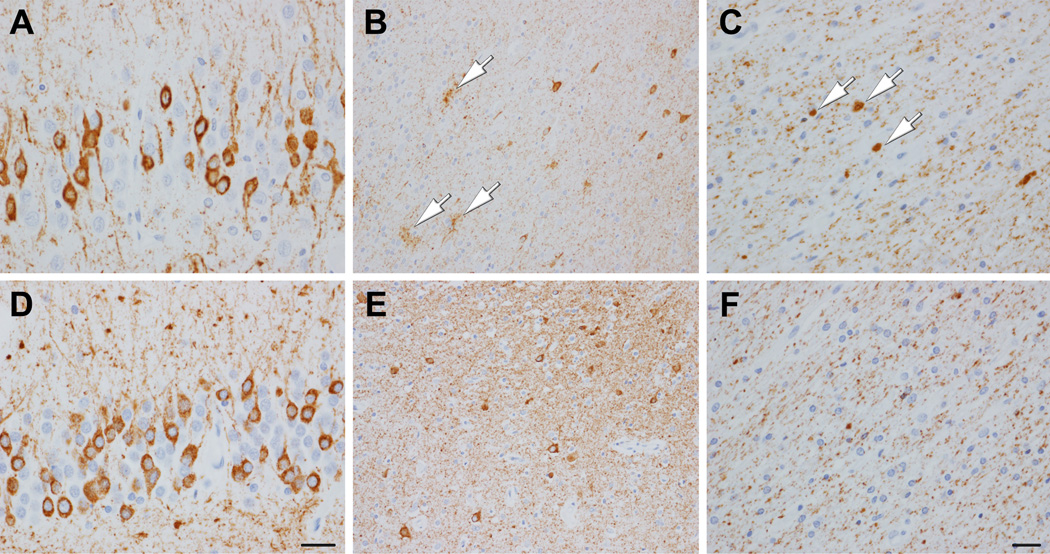

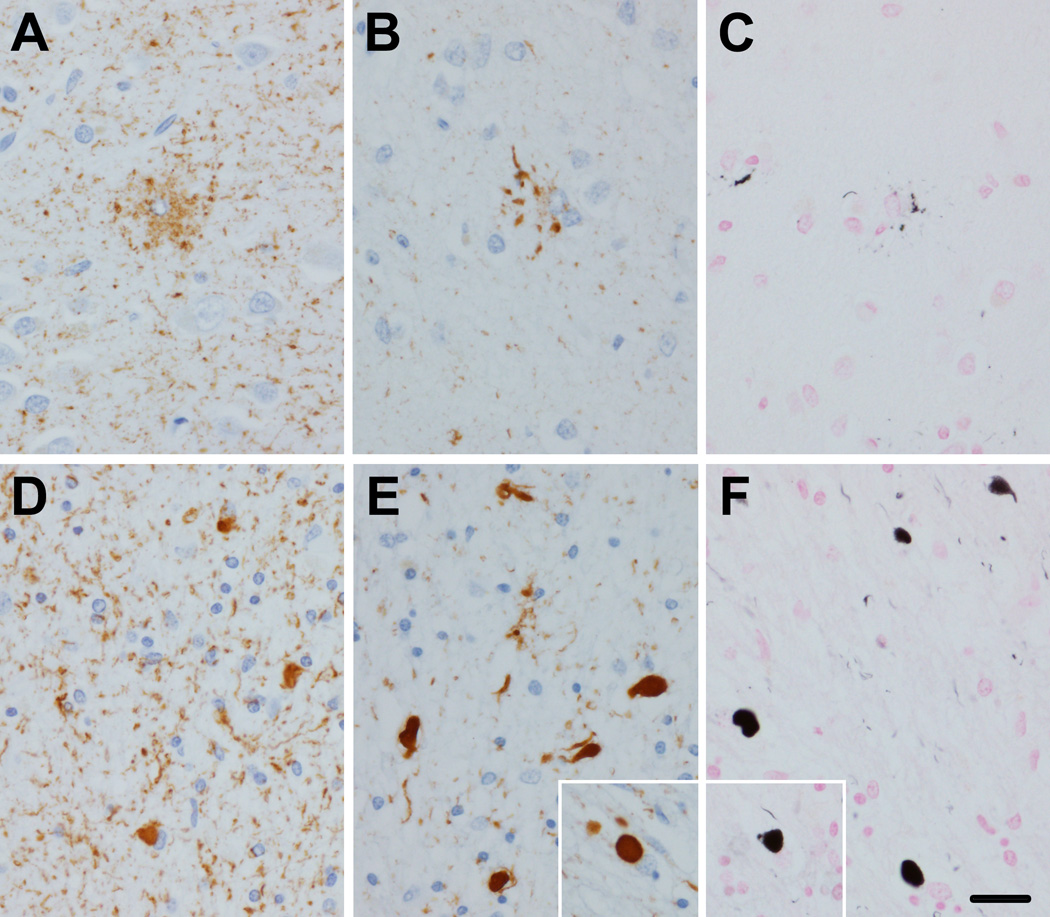

Tau IHC revealed a range of lesions, including a few grain-like lesions, a few neurofibrillary tangles, more common pretangles, and numerous threads. Glial pathology included sparse coiled bodies (CB) and more numerous GOI and GAI (Figure 2), which were strongly positive for 4R tau, but negative for 3R tau. GAI had minimal argyrophilia with Gallyas silver stain, whereas GOI and CB stained positively (Figure 3). Distribution of GOI included, among other regions, the frontal lobe, motor cortex and corticospinal tract at the level of the lower brainstem. In general, tau pathology was abundant in both gray and white matter.

Figure 2.

Immunohistochemistry with phospho-tau (CP13) of Patient 1 (A, B, C) and Patient 2 (D, E, F). Both patients have numerous pretangles (diffuse granular cytoplasmic immunoreactivity) in the dentate fascia (A, D), with extensive neuropil threads. The temporal neocortex in Patient 1 has neuropil threads, pretangles and GAI (B, arrows). The temporal neocortex in Patient 2 has many pretangles and neuropil threads (E). Temporal white matter of Patient 1 has GOI (C, arrows) and diffusely granular of tau immunoreactivity. Gray and white matter have similar tau burden. Temporal white matter in Patient 2 (F) shows diffusely granular of tau immunoreactivity, but no oligodendroglial lesions. Tau burden is greater in gray matter than white matter. (Bar in D = 50 µm, same for A; bar in F = 20 µm, same for B, C, and E)

Figure 3.

GGT like tau pathology in Patient 1. Immunohistochemistry of temporal neocortex with phospho-tau (CP13) shows GAI, with coarsely granular cytoplasmic processes (A). Immunohistochemistry for 4R tau (RD4) shows coarse granular staining of cell processes of GAI (B). Gallyas silver stain shows paucity of staining of GAI (C). In white matter phospho-tau shows many GOI as well as many cell processes with granular immunoreactivity (D). GOI have strong immunoreactivity with 4R tau (E, inset shows typical spherical GOI). GOI have robust argyrophilia with Gallyas stain (F, inset shows typical spherical GOI). Bar in F = 50 µm, same for A, B, C, D and E, and insets)

Summary of clinical and laboratory findings of other p.P301L mutation carriers

The seven other p.P301L mutation carriers included five men and two women. All Individuals were white. Patient 2 was of Hispanic ethnicity. Their average age at symptomatic onset was 49 years (42–56), and average disease duration was 8.5 years (3–14). Patients 2–4 were right-handed, and no information was available on the handedness of the remaining patients. Clinically, all patients presented with FTD syndromes. The most frequent FTD type based on the initial clinical presentation was bvFTD. It included changes in behavior and personality, poor executive functions, loss of judgment and insight, obsessive-compulsive behavior, impulsiveness, irritability, inattentiveness, disinhibition, social withdrawal, and apathy. Only Patient 8 presented at onset with language impairment that included anomia, reduced comprehension, surface dyslexia, but fluent speech and was suggestive of semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia (svPPA). His subsequent behavioral changes included anger outbursts and increased consumption of sweets. Of note, Patients 3, 5 and 7 developed later in the disease course secondary semantic dysfunction that included impairment of language comprehension, but not fluency, anomia, and surface dyslexia. Seven patients had parkinsonian features, but none had either features of motor neuron disease or gaze palsy. Patients 3 and 8 had generalized seizures, which were refractory in Patient 8. Trials of antidepressant, dopaminergic, anti-dementia, antioxidants and antipsychotic medications and mood stabilizers were unsuccessful. Brain imaging included MRI, FDG-PET and 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT were consistent with FTD. All seven patients had a positive family history of early-onset dementia. Patients 6 and 8 were siblings and Patient 7 was their cousin. The remaining patients were unrelated. Five carriers had a H1/H2 MAPT genotype and two were homozygous for the MAPT H1 haplotype. Their APOE genotype was ε3/ε3, except for ε3/ε4 of Patient 3.

Summary of neuropathologic findings of other p.P301L mutation carriers

The average calculated whole fixed brain weight was 1036 grams (880– 1190). Macroscopically, brains of all seven patients showed varying degrees of cortical atrophy of frontal and temporal lobes that in five patients resembled the pattern seen in PiD, with sparing of peri-Rolandic cortices and the posterior part of the superior temporal gyrus (Figure 1). All brains showed dilatation of the lateral ventricles and caudate nucleus atrophy. In most cases there was striking atrophy of middle and inferior temporal gyri, which contrasted with a relatively well-preserved hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus (Figure 1). Except for Patient 4, the substantia nigra had loss of neuromelanin depigmentation (Figure 1). The motor cortex was atrophic in Patients 4 and 8.

Microscopically, the hippocampus in Patients 3 and 8 was remarkable for neuronal loss and gliosis in CA1-CA4, with dispersion of dentate fascia neurons; in Patient 4 there was focal dentate fascia neuronal dispersion. Alzheimer-type neurofibrillary pathology was either absent or mild. Patients 2 and 4 had moderate to severe neuronal loss in the subthalamic nucleus. The substantia nigra showed varying degrees of neuronal loss, but no Lewy bodies. Except for Patient 5, tau pathology largely predominated in the cortical gray matter compared with the white matter. Almost all neuronal inclusions resembled pretangles, with only a few well-formed tangles. The lesions were mostly invisible with thioflavin S fluorescent microscopy. Granular fuzzy astrocytes (GFA) were the most frequent form of astrocytic tau pathology. Rare or at most sparse CB were noted in all patients. Patient 2 had astrocytes with proximal granular inclusions with tau immunohistochemistry, and Patient 5 had lesions that resembles tufted astrocytes. In four patients ballooned neurons were frequent.

Discussion

All eight patients in this study, including five unrelated and three related, were carriers of a c.902C>T mutation (p.P301L) in the MAPT gene, but they had varying clinicopathologic presentations. This is one of the largest series of unrelated autopsied p.P301L carriers published to date. This reflects the fact that our brain bank is a major referral site in North America for neurodegenerative tauopathies [11]. Patient 1 had clinical and neuropathologic features consistent with GGT [10]. This is the first report on GGT caused by the p.P301L mutation. To date thirty-nine sporadic [10, 13–15] and nine carriers of two exon 11 MAPT mutations (p.K317N (c.951G>C) [9] and p.K317M (c.950A>T) [12]) have been associated with a GGT phenotype. Of note, until recently GGT was considered a sporadic condition [10].

Compared to Patient 1 with p.P301L from this study, the p.K317N carrier was also a woman who died at 69 years of age following a shorter disease course of five years [9]. The eight family members with p.K317M included five men and three women with a mean age of symptomatic onset of 50 years and a mean disease duration of six years [12]. Patient 1 presented initially with bvFTD, whereas behavior and personality changes were not prominent in p.K317N and p.K317M carriers [9, 12]. Motor neuron disease and parkinsonism were noted in all ten hereditary patients with GGT [9, 12]. Patient 1 and the p.K317N carrier were homozygous for the H1 MAPT haplotype [9], while no data was available for p.K317M patients [12]. Clinicopathological and genetic findings of the ten hereditary GGT cases due to MAPT mutations is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of hereditary GGT cases due to MAPT mutations

| MAPT mutation |

p.P301L (c.902C>T) [Patient 1 from the present study] |

p.K317N (c.951G>C) [9] | p.K317M (c.950A>T) [12] |

| Number of cases | 1 | 1 | 8* |

| Sex | F | F | 5M & 3F |

| Age of onset (y) | 53 | 64 | 50 (range 39– 57) |

| Duration (y) | 12 | 5 | 6 (range 3– 11) |

| Initial presentation | personality/ behavior changes, short-term memory loss |

speech apraxia | dysarthria (n=5/8), hypokinesia (n= 2/8), tremor (n= 3/8) |

| FTD type** | bvFTD | PPAOS | MND, P (PSP, CBS) |

| Parkinsonism (symmetry) [dopaminergic responsiveness] |

hypomimia, postural instability, gait freezing, bradykinesia, rigidity, hand tremor (asymmetric L > R) [no] |

axial rigidity, postural instability, bradykinesia (symmetric) [no] |

generalized parkinsonism (n=8/8), including tremor, bradykinesia, postural instability (asymmetric in several cases) [no] |

| MND features (symmetry) | upper motor neuron syndrome: bilateral spastic contractures(asymmetric L > R) |

upper & lower motor neuron syndrome: fasciculations, spastic dysarthria (symmetric) |

upper (n=8/8)& lower motor neuron syndrome (amyotrophy)(n= 6/8) |

| Other signs & symptoms | long-term memory loss, dysphagia, secondary semantic dysfunction, dyscalculia, incontinence |

mild cognitive impairment, supranuclear gaze palsy, limb apraxia, apraxia of eyelid opening, frontal release signs |

ideomotor apraxia (n= 1/8), loss of verbal fluency (n=3/8), anomia (n=2/8), mutism (n= 2/8), echolalia (n= 1/8), dysphagia (n= 2/8), supranuclear gaze palsy (n= 3/8), eyelids apraxia (n= 1/8), hand dystonia (n= 1/8), focal reflex myoclonus (n= 1/8), spastic dysphonia (n= 1/8), apathy (n= 1/8), emotional lability (n= 3/8), compulsive feeding (n= 1/8) |

| Family history of early onset dementia |

mother, maternal grandmother | mother, maternal aunt | 13 cases from one family |

| MAPTgenotype | H1/H1 | H1/H1 | N/A |

| Brain weight (g) | 880 | 1220 | N/A |

| Braak stage | 0 | III | N/A |

| Thal phase | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cortical atrophy | lobar: severe frontal (esp. superior frontal, precentral & frontal pole); mild temporal & parietal |

lobar: severe frontal (esp. inferior frontal & precentral); mild temporal & parietal |

lobar: severe frontal &inferior frontal (n=1/8); moderate frontal,but severe precentral (n= 1/8); moderate temporal pole & inferior temporal (n=1/8); sever frontal (n=1/8); unremarkable (n= 4/8) |

| MTR/CST degeneration | severe/mild | severe/ mild | severe (n= 4/8), moderate (n= 4/8)/ severe (6/8), mild (n= 1) |

| Hippocampal atrophy | none | none | N/A |

| Subthalamic neuron loss | severe | minimal | N/A |

| Substantia nigra pigmentation (macroscopic) |

decreased | decreased | decreased (n= 8/8) |

| Substantia nigra neuron loss |

severe | moderate | severe (n= 8/8) |

| GOI | G(+); 4R(+); 3R(−) | G(±); 4R(+); 3R(−) | N/A*** |

| GAI | G(±);4R(+); 3R(−) | G(+); 4R(+);3R(−) | N/A*** |

| Other features | moderate CN atrophy; BN | milde CN atrophy, no BN | severe neuron loss in the motor bulbar nuclei and in the spinal anterior horn, demyelination of spinal anterolateral columns, no BN. |

| GGT subtype | III | III | III**** |

Abbreviations.

13 family members with p.K317M mutation, of whom eight were autopsied;

defined on the basis of leading features at the initial clinical presentation;

on Western blot two bands of 68 & 64 kDa consistent with 4R tau in [12], in subsequent immunohistochemical analysis [23] in p.K317M: 4R positive globular astro- and oligodendroglial inclusions with a few 3R positive oligodendroglial globular inclusions;

at least some of the eight cases represented GGT subtype III;

3R = three repeat tau isoform; 4R = four repeat tau isoform; BN = ballooned neurons; bvFTD = behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia; CBS = corticobasal syndrome; CN = caudate nucleus; CST = corticospinal tract; g = grams; F = female; FTD = frontotemporal dementia; G = Gallyas silver stain; GAI = globular astrocytic inclusions; GGT = globular glial tauopathy; GOI = globular oligodendroglial inclusions; L = left; M = male; MND = motor neurone disease; MTR = motor cortex; N/A = not available; P = parkinsonism; PPAOS = progressive apraxia of speech; PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy; R = right; y. = years

In contrast to Patient 1, the brain weight of the p.K317N carrier was within normal limits. Both brains showed frontotemporal lobar atrophy, as did half of p.K317M carriers (Table 4). Moreover, involvement of superior frontal gyrus and premotor cortex in Patient 1 resembled the atrophy pattern of CBD.

On tau IHC, there was widespread pathology in neurons and glia with GOI and GAI in all ten hereditary GGT cases [9, 12] (Table 4). In Patient 1 and p.K317N carrier, GOI and GAI were immunoreactive for 4R tau, but not 3R tau. GAI in p.K317N were argyrophilic [9] with Gallyas silver staining, whereas GAI in Patient 1 were mostly negative. These results suggest that Patient 1 could be referred to as “GGT caused by MAPT mutation” rather than “frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) with MAPT mutations” [10]. This distinction, however, seems to be largely semantic. Neither the Gallyas method nor IHC were included in the analysis of p.K317M [12]. On the other hand, a subsequent immunohistochemical study showed virtually indistinguishable characteristics of glial lesions in sporadic GGT individuals and p.K317M carriers in terms of a pattern of tau phosphorylation sites, conformation, truncation, and ubiquitination [23]. Patients with p.P301L and p.K317N and at least some the eight autopsied p.K317M carriers (see Table 2 and Figure 4 in [12]) were consistent with GGT subtype III (Table 4) [10].

There were no significant differences between Patient 1 with p.P301L from this study and previously published sporadic patients with GGT, including five patients from the Mayo Clinic brain bank [9, 10, 13–15, 18]. All sporadic patients with GGT had frontotemporal lobar atrophy with a brain weights ranging from 960 to 1300 grams [9, 10, 13–15, 18, 19]. The abundant 4R tau glial pathology in the five patients from the Mayo series all had Gallyas-positive GOI. In contrast, GAI were Gallyas-negative in three patients, and either argyrophilic or weakly argyrophilic in two patients [9]. GGT subtype III was found in three patients, while two patients had features of subtype I, the most common GGT subtype [9, 10]. Sporadic GGT reported to date have presented with FTD syndromes, predominantly with bvFTD, followed by agrammatic variant of primary progressive aphasia [9, 10, 13, 14, 18, 19]. In one patient, svPPA was diagnosed [15]. The overwhelming majority of sporadic GGT patients were homozygous for the H1 MAPT haplotype [9, 18, 19].

The clinicopathologic presentations of Patients 2 through 8 in this series were consistent with FTDP-17, but differed from Patient 1 [20]. Brains of Patients 2 through 8 also showed frontotemporal atrophy, but its pattern was more reminiscent of PiD, with sparing of the posterior parts of the superior temporal gyrus (Figure 1). A similar distribution of atrophy has been reported in a number of reports on p.P301L, notably in family member III-1 from the study of Bird et al. [21] and Family 2 member III:3 from the analysis of van Swieten et al. [16]. In general, p.P301L brains were thought to show little variation in appearance and severity of atrophy [16, 21, 22], which manifests early in the disease course. The typical course is five to ten years and is usually a rapidly progressive process [16].

Unlike Patient 1, tau pathology in the other patients affected gray matter more than white matter (Figure 2, Table 3) and the sparse glial tau pathology had the morphology of CB and GFA rather than of GOI or GAI of Patient 1 (Table 2). Two other forms of astrocytic lesions from our series were astrocytes with proximal granular inclusions in Patient 2 and tufted astrocytes in Patient 5. Most descriptions of the neuropathology of p.P301L carriers provide minimal information about glial tau pathology, suggesting that they are not usually a prominent neuropathologic feature. Although 4R tauopathies in general are characterized by both neuronal and glial pathology [16], it has been suggested that MAPT exon 10 missense mutations, including p.P301L, have less extensive glial pathology than exon 10 splice site mutations [17]. This was observed for all but two (Patients 1 and 5) of the eight patients from this series (Table 2 and 3). Glial tau pathology in p.P301L carriers has been described as “oligodendroglial inclusions,” “tau-positive glial inclusions,” “glial tangles” or “tau deposits in glial cells” that were either occasional [16] or abundant [24, 25]. In a few reports more specific terms were used, such as astrocytic plaque-like structures [22, 26, 27], tuft-shaped astrocytes [26], and astrocytes with proximal granular inclusions [23].

As in previously reported p.P301L carriers [21, 22, 25–28], the morphology of neuronal tau pathology in eight patients from this series was predominantly that of pretangles, with diffuse granular cytoplasmic immunoreactivity in a somatodendritic domain (Figure 2). Additionally, 4R tau cytoplasmic inclusions or aggregates referred to as non-argentophilic Pick-like bodies [25] or argentophilic ubiquitin-negative mini-Pick-like bodies were identified in the dentate gyrus of a few p.P301L carriers [26, 27, 29]. In general, MAPT mutations that affect only 4R tau or are associated with overexpression of 4R tau produce neuronal tau pathology that consists mostly of pretangles. In contrast, Alzheimer-type tangles tend to occur in MAPT mutations that affect all six isoforms [16, 25]. Our study confirms previous observations on frequent occurrence of ballooned neurons in P301L (Table 2) [21, 22, 25–27, 30].

In most FTDP-17 cases, the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus are relatively spared [25]. In this study all patients except Patient 3 showed either relative or total preservation of the hippocampus that contrasted with more severe atrophy of the middle and inferior temporal gyri (Table 2). In the correct circumstance, this feature may be suggestive of p.P301L. This pattern of neocortical atrophy has been noted in a number of previous reports of p.P301L carriers: in Patient 1 in the study by Mirra et al. (see Fig. 4b in [22]), Patient II-1 in the report by Kodama et al. (see Fig. 2a in [28]), and in a patient described by Ferrer et al. (see Fig. 1A in [27]). Sparing of the hippocampus with prominent or at least moderate involvement of the temporal lobe has commonly been reported in p.P301L carriers [16, 21, 22, 24, 28, 30].

Like in many previous publications on p.P301L, all eight brains from this study had reduced weight (median weight of 1015 grams (range 876– 1188 grams) vs.1035 grams in 14 patients from hereditary frontotemporal dementia Family I [30], 915 grams in Patient 1, and 1060 grams in Patient 2 [22]). Variable caudate nucleus atrophy and moderate to marked enlargement of the lateral ventricles were observed in all eight patients from this series (Table 2) and in most previously reported p.P301L carriers [16, 22, 25, 28, 30]. Three out of the eight patients from this study had neuronal loss in the subthalamic nucleus, which was severe in two patients. In most p.P301L carriers from the literature, the subthalamic nucleus was only mildly affected [21, 22]. Our series confirmed frequent degeneration of the substantia nigra in FTDP-17 due to p.P301L mutation (Table 2) [16]. Despite degeneration, most p.P301L carriers do not have prominent parkinsonian features, at least early in the disease [16, 21, 25, 30, 31]. In our series, parkinsonism was observed only in two patients and gaze palsy was absent. The latter has rarely been seen in p.P301L carriers [25]. The most common clinical presentation in both the present series and published studies was bvFTD (Table 1) [16, 25, 28, 30]. Patient 8 from our study had language impairment and anomia suggestive of svPPA, which in patients with tauopathies is rarely seen, if ever, in PiD, a 3R tauopathy [15]. Except for Patient 1 with GGT, no signs of upper motor dysfunction were documented; however, motor cortex atrophy or corticospinal tract degeneration was also observed in Patients 3, 4 and 8. Pyramidal signs have rarely been noted in p.P301L carriers and mainly in the late stage of the disease [30].

Patients 3 and 8 from this series had generalized seizures and both had pathologic features of hippocampal sclerosis with dentate fascia neuronal dispersion. Of note, epileptic seizures are rare in FTDP-17, but have been reported in carriers of another MAPT codon 301 mutation, p.P301S [32].

Our study confirms previous observations on intra- and inter-familial phenotypic heterogeneity of p.P301L carriers, but its explanation is largely unknown [31]. It is likely that environmental or genetic factors other than the mutation play a role in the phenotypic diversity. Disease duration may be a contributing factor. Individuals with p.P301L mutation and longer disease durations seem to have more severe clinicopathologic findings [25]. Other factors to consider are MAPT and APOE haplotypes as well as race. Of the two major MAPT haplotypes, H2 occurs in Caucasian populations with allele frequencies of 20%–30% and in of less than 5% in Asian populations [33]. All eight patients from this study were white, as are the majority of previously reported p.P301L carriers [30]. Previous reports showed that p.P301L may be more frequent on the H2 haplotype [33]; however, there are a number of reported patients with H1 haplotype [29, 31, 33]. In our series, the H1/H2 genotype was identified in five p.P301L carriers, whereas three individuals were homozygous for H1 haplotype (Table 1). Previous suggestions that H1 is associated with parkinsonism and H2 with dementia in p.P301L carriers [33] could not be confirmed either in our series or in Asian patients with p.P301L and H1 haplotype who had dementia as the most common phenotype [28, 31, 34]. The APOE ε4 allele is considered a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer-type pathology and reducing the average age of onset [35, 36]. This observation could not be confirmed either by Bird et al. [21] or Patient 3 from our series.

In conclusion, the major finding of this study is that MAPT p.P301L mutation is associated with clinical and pathologic heterogeneity, including a GGT phenotype that is indistinguishable from sporadic GGT. This finding confirms previous observations that GGT is not always a sporadic condition, but can be caused by MAPT mutations. Sparing of the hippocampus with severe involvement of adjacent inferior and middle temporal gyri is the most striking macroscopic finding suggestive of p.P301L mutation. The p.P301L mutation may lead to different clinicopathologic phenotypes in both unrelated and related carriers. It is likely that some environmental and genetic factors other than the mutation itself play a role in the phenotypic heterogeneity of the p.P301L carriers.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients, family members, and caregivers who agreed to brain donation; without their donation these studies would have been impossible. We also acknowledge expert technical assistance of Linda Rousseau and Virginia Phillips for histology and Monica Castanedes-Casey for immunohistochemistry.

This study was founded by NIH grants P50-NS072187 and P50-AG016574. PT is supported by a Jaye F. and Betty F. Dyer Foundation Fellowship in progressive supranuclear palsy research, an Allergan Medical Educational Grant, and a Max Kade Foundation postdoctoral fellowship. MEM is supported by the Florida Department of Health, Ed and Ethel Moore Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program (6AZ01). OAR is supported by the NIH grant R01-NS078086. ZKW is supported by the grants NIH/NIA (primary) and NIH/NINDS (secondary) 1U01AG045390-01A1, the Mayo Clinic Center for Regenerative Medicine, the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, the Mayo Clinic Neuroscience Focused Research Team (Cecilia and Dan Carmichael Family Foundation, and the James C. and Sarah K. Kennedy Fund for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at the Mayo Clinic in Florida), the gift from Carl Edward Bolch, Jr., and Susan Bass Bolch, and the Sol Goldman Charitable Trust. DSK serves on a Data Safety Monitoring Board for Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals and for the DIAN study; is an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Biogen, TauRX Pharmaceuticals, Lilly Pharmaceuticals and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study; and receives research support from the NIH. RCP works as a consultant for Roche, Inc., Merck, Inc., Genentech, Inc., Biogen, Inc., and Eli Lilly Company.

List of abbreviations

- 3R tau

three repeat tau isoforms

- 4R tau

four repeat tau isoforms

- APOE

apolipoprotein E gene

- bvFTD

behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia

- CA

Cornu ammonis

- CB

coiled bodies

- CBD

corticobasal degeneration

- FDG-PET

fludeoxyglucose brain positron emission tomography

- FTD

frontotemporal dementia

- FTDP-17

frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

- GAI

globular astrocytic inclusions

- GFA

granular, fuzzy astrocytes

- GGT

globular glial tauopathy

- GOI

globular oligodendroglial inclusions

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MAPT

microtubule-associated protein tau gene

- MND

motor neuron disease

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PiD

Pick’s disease

- svPPA

semantic variant of primary progressive aphasia

- 99mTc-HMPAO SPECT

technetium hexamethylpropylene-amine-oxime single-photon emission computed tomography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests

None.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed substantially to this research study. Study concept and design (DWD). Drafting of the manuscript (PT). Acquisition of clinical data (PT, DSK, RCP). Acquisition of genetic data (PT, MSC). Acquisition of neuropathologic data (DWD, JEP, MEM, PT, MDT). Analysis and interpretation of clinical data (DSK, RCP, ZKW, PT). Analysis and interpretation of genetic data (OAR, RR, PT, MSC). Analysis and interpretation of neuropathologic data (DWD, JEP). Revising of the manuscript (PT, MSC, MDT, MEM, RR, OAR, ZKW, JEP, DSK, RCP, DWD).

References

- 1.Foster NL, Wilhelmsen K, Sima AA, Jones MZ, D'Amato CJ, Gilman S. Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: a consensus conference. Conference Participants. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:706–715. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreadis A, Brown WM, Kosik KS. Structure and novel exons of the human tau gene. Biochemistry. 1992;31:10626–10633. doi: 10.1021/bi00158a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghetti B, Oblak AL, Boeve BF, Johnson KA, Dickerson BC, Goedert M. Invited review: Frontotemporal dementia caused by microtubule-associated protein tau gene (MAPT) mutations: a chameleon for neuropathology and neuroimaging. Neuropath Appl Neuro. 2015;41:24–46. doi: 10.1111/nan.12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Goedert M. Tau proteins with FTDP-17 mutations have a reduced ability to promote microtubule assembly. Febs Lett. 1998;437:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goedert M, Jakes R, Crowther RA. Effects of frontotemporal dementia FTDP-17 mutations on heparin-induced assembly of tau filaments. Febs Lett. 1999;450:306–311. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spina S, Farlow MR, Unverzagt FW, Kareken DA, Murrell JR, Fraser G, Epperson F, Crowther RA, Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Ghetti B. The tauopathy associated with mutation +3 in intron 10 of Tau: characterization of the MSTD family. Brain. 2008;131:72–89. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tacik P, DeTure M, Hinkle KM, Lin WL, Sanchez-Contreras M, Carlomagno Y, Pedraza O, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW. A Novel Tau Mutation in Exon 12, p.Q336H, Causes Hereditary Pick Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:1042–1052. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouri N, Carlomagno Y, Baker M, Liesinger AM, Caselli RJ, Wszolek ZK, Petrucelli L, Boeve BF, Parisi JE, Josephs KA, Uitti RJ, Ross OA, Graff-Radford NR, DeTure MA, Dickson DW, Rademakers R. Novel mutation in MAPT exon 13 (p.N410H) causes corticobasal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:271–282. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1193-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tacik P, DeTure M, Lin WL, Sanchez Contreras M, Wojtas A, Hinkle KM, Fujioka S, Baker MC, Walton RL, Carlomagno Y, Brown PH, Strongosky AJ, Kouri N, Murray ME, Petrucelli L, Josephs KA, Rademakers R, Ross OA, Wszolek ZK, Dickson DW. A novel tau mutation, p.K317N, causes globular glial tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:199–214. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed Z, Bigio EH, Budka H, Dickson DW, Ferrer I, Ghetti B, Giaccone G, Hatanpaa KJ, Holton JL, Josephs KA, Powers J, Spina S, Takahashi H, White CL, 3rd, Revesz T, Kovacs GG. Globular glial tauopathies (GGT): consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:537–544. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Josephs KA, Dickson DW. Diagnostic accuracy of progressive supranuclear palsy in the Society for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy brain bank. Mov Disord. 2003;18:1018–1026. doi: 10.1002/mds.10488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarranz JJ, Ferrer I, Lezcano E, Forcadas MI, Eizaguirre B, Atares B, Puig B, Gomez-Esteban JC, Fernandez-Maiztegui C, Rouco I, Perez-Concha T, Fernandez M, Rodriguez O, Rodriguez-Martinez AB, de Pancorbo MM, Pastor P, Perez-Tur J. A novel mutation (K317M) in the MAPT gene causes FTDP and motor neuron disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1578–1585. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000160116.65034.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi R, Toyoshima Y, Tada M, Tanaka H, Shimizu H, Shiga A, Miura T, Aoki K, Aikawa A, Ishizawa S, Ikeuchi T, Nishizawa M, Kakita A, Takahashi H. Globular Glial Mixed Four Repeat Tau and TDP-43 Proteinopathy with Motor Neuron Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Brain Pathol. 2016;26:82–94. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark CN, Lashley T, Mahoney CJ, Warren JD, Revesz T, Rohrer JD. Temporal Variant Frontotemporal Dementia Is Associated with Globular Glial Tauopathy. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2015;28:92–97. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0000000000000060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graff-Radford J, Josephs KA, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Giannini C, Boeve BF. Globular Glial Tauopathy Presenting as Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia. Jama Neurol. 2016;73:123–125. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Swieten JC, Stevens M, Rosso SM, Rizzu P, Joosse M, de Koning I, Kamphorst W, Ravid R, Spillantini MG, Niermeijer MF, Heutink P. Phenotypic variation in hereditary frontotemporal dementia with tau mutations. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:617–626. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199910)46:4<617::aid-ana10>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goedert M. Tau gene mutations and their effects. Movement Disord. 2005;20:S45–S52. doi: 10.1002/mds.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs GG, Majtenyi K, Spina S, Murrell JR, Gelpi E, Hoftberger R, Fraser G, Crowther RA, Goedert M, Budka H, Ghetti B. White matter tauopathy with globular glial inclusions: a distinct sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:963–975. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318187a80f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmed Z, Doherty KM, Silveira-Moriyama L, Bandopadhyay R, Lashley T, Mamais A, Hondhamuni G, Wray S, Newcombe J, O'Sullivan SS, Wroe S, de Silva R, Holton JL, Lees AJ, Revesz T. Globular glial tauopathies (GGT) presenting with motor neuron disease or frontotemporal dementia: an emerging group of 4-repeat tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:415–428. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0857-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spillantini MG, Bird TD, Ghetti B. Frontotemporal Dementia and Parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17: A new group of tauopathies. Brain Pathol. 1998;8:387–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1998.tb00162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bird TD, Nochlin D, Poorkaj P, Cherrier M, Kaye J, Payami H, Peskind E, Lampe TH, Nemens E, Boyer PJ, Schellenberg GD. A clinical pathological comparison of three families with frontotemporal dementia and identical mutations in the tau gene (P301L) Brain. 1999;122:741–756. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirra SS, Murrell JR, Gearing M, Spillantini MG, Goedert M, Crowther RA, Levey AI, Jones R, Green J, Shoffner JM, Wainer BH, Schmidt ML, Trojanowski JQ, Ghetti B. Tau pathology in a family with dementia and a P301L mutation in tau. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:335–345. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199904000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrer I, Lopez-Gonzalez I, Carmona M, Arregui L, Dalfo E, Torrejon-Escribano B, Diehl R, Kovacs GG. Glial and neuronal tau pathology in tauopathies: characterization of disease-specific phenotypes and tau pathology progression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2014;73:81–97. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spillantini MG, Crowther RA, Kamphorst W, Heutink P, van Swieten JC. Tau pathology in two Dutch families with mutations in the microtubule-binding region of tau. American Journal of Pathology. 1998;153:1359–1363. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65721-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasreddine ZS, Loginov M, Clark LN, Lamarche J, Miller BL, Lamontagne A, Zhukareva V, Lee VM, Wilhelmsen KC, Geschwind DH. From genotype to phenotype: a clinical pathological, and biochemical investigation of frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism (FTDP-17) caused by the P301L tau mutation. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:704–715. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199906)45:6<704::aid-ana4>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamec E, Murrell JR, Takao M, Hobbs W, Nixon RA, Ghetti B, Vonsattel JP. P301L tauopathy: confocal immunofluorescence study of perinuclear aggregation of the mutated protein. J Neurol Sci. 2002;200:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferrer I, Hernandez I, Boada M, Llorente A, Rey MJ, Cardozo A, Ezquerra M, Puig B. Primary progressive aphasia as the initial manifestation of corticobasal degeneration and unusual tauopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;106:419–435. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0756-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kodama K, Okada S, Iseki E, Kowalska A, Tabira T, Hosoi N, Yamanouchi N, Noda S, Komatsu N, Nakazato M, Kumakiri C, Yazaki M, Sato T. Familial frontotemporal dementia with a P301L tau mutation in Japan. J Neurol Sci. 2000;176:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llado A, Sanchez-Valle R, Rey MJ, Ezquerra M, Tolosa E, Ferrer I, Molinuevo JL, Grp CCS. Clinicopathological and genetic correlates of frontotemporal lobar degeneration and corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol. 2008;255:488–494. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heutink P, Stevens M, Rizzu P, Bakker E, Kros JM, Tibben A, Niermeijer MF, vanDuijn CM, Oostra BA, vanSwieten JC. Hereditary frontotemporal dementia is linked to chromosome 17q21-q22: A genetic and clinicopathological study of three Dutch families. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:150–159. doi: 10.1002/ana.410410205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi T, Mori H, Okuma Y, Dickson DW, Cookson N, Tsuboi Y, Motoi Y, Tanaka R, Miyashita N, Anno M, Narabayashi H, Mizuno Y. Contrasting genotypes of the tau gene in two phenotypically distinct patients with P301L mutation of frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17. J Neurol. 2002;249:669–675. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0687-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperfeld AD, Collatz MB, Baier H, Palmbach M, Storch A, Schwarz J, Tatsch K, Reske S, Joosse M, Heutink P, Ludolph AC. FTDP-17: An early-onset phenotype with parkinsonism and epileptic seizures caused by a novel mutation. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:708–715. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<708::aid-ana5>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walker RH, Friedman J, Wiener J, Hobler R, Gwinn-Hardy K, Adam A, DeWolfe J, Gibbs R, Baker M, Farrer M, Hutton M, Hardy J. A family with a tau P301L mutation presenting with parkinsonism. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;9:121–123. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(02)00003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka R, Kobayashi T, Motoi Y, Anno M, Mizuno Y, Mori H. A case of frontotemporal dementia with tau P301L mutation in the Far East. J Neurol. 2000;247:705–707. doi: 10.1007/s004150070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roses AD. Apolipoprotein-E Affects the Rate of Alzheimer-Disease Expression - Beta-Amyloid Burden Is a Secondary Consequence Dependent on Apoe Genotype and Duration of Disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:429–437. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199409000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar NT, Liestol K, Loberg EM, Reims HM, Maehlen J. Apolipoprotein E allelotype is associated with neuropathological findings in Alzheimer's disease. Virchows Arch. 2015;467:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s00428-015-1772-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]