Abstract

Advancement in imaging techniques and interventional cardiology procedures have generated renewed interest in anatomy of tricuspid valve complex. The purpose of the present study was to characterize the morphology of tricuspid valve leaflets using objective criteria. Thirty-six embalmed cadaveric hearts were utilized for the present study. Leaflet morphology was studied using newly defined criteria. Commissural zones were identified and leaflets were delineated. Presence of scallops was also recorded. Single leaflet was observed in six cases, double in 26 cases, and triple in four cases. The anterior leaflet is large with multiple scallops and frequently accrues portion of inferior leaflet. The septal leaflet is in the form of a plateau and also frequently accrues parts of inferior leaflet. The inferior leaflet rarely occurs as independent leaflet. A wide un-indented basal zone exists across the valve leaflets. The study found that the tricuspid valve is rarely tricuspid. It also generated the hypotheses that the tricuspid valve does not open completely due to presence of a wide basal zone and the valve does not close completely owing to incongruence and lack of coaptation of leaflets. The findings provide clear understanding of leaflet morphology of tricuspid valve. This will help imaging specialists for interpretation of images and cardiologists for interventional procedures. The findings also enhance our understanding of pathophysiology of conditions like functional tricuspid regurgitation.

Keywords: Annulus, Commissure, Leaflet, Scallop

Introduction

The right atrio-ventricular valve has been traditionally referred to as having three cusps in all standard anatomical texts. The three leaflets referred to as anterior, inferior, and septal, conform to the anterior/sterno-costal, inferior/diaphragmatic, and septal walls of right ventricle, respectively. The leaflets are said to be separated by three commissures and fit snugly together; the pattern of zone of apposition confirms the trifoliate arrangement of right atrio-ventricular valve [1,2,3]. However, this standard description has been challenged by some [4,5,6,7,8].

While studying the literature and observing the human tricuspid valves during routine anatomical dissections, it was observed that the tricuspid valve leaflets do not usually comply to their respective surfaces. The commissures (a widely used and accepted term) between the adjacent leaflets also do not conform to their accepted positions. Review of literature revealed that commissure, though a widely used term that delineates the cusps, has been hardly elaborated upon.

It is also widely accepted that chordae tendinae arising from apex of papillary muscle gains attachment to the depth of commissure [9,10,11]. Romanes described commissures as lines at which adjacent valves leaflets are continuous with each other at their bases [3].

However, papillary muscles, on which the definition of a commissure rests, are documented to be highly variable. While describing the variability of cuspal tissue and cordal/papillary support of this valve Victor and Nayak [5] have likened the interior of right ventricle “as unique to each individual as one's fingerprints.” Joudinaud et al. [6] also reported that “endless variations were found in number, size, shape, fusion, and location of papillary muscles.” Needless to say that morphology of the valve can be described only after unambiguous description of its constituent parts that is commissure and leaflets. The present study was planned to characterize the tricuspid valve morphology based on newly defined criteria for commissures, leaflets, and scallops.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted on 36 adult human hearts procured from the collection of embalmed cadavers available in the Department of Anatomy. Since the heart specimens were already removed from the cadaver before the commencement of the study, the sex could not be ascertained. Hearts with any grossly identifiable anomaly and calcific tricuspid valves were excluded from the study. Hearts were cleaned and cleared from any clots within the chambers. The right atrium and the right ventricle were opened.

The junctional areas between the three walls of the right ventricles viz anterior, inferior, and septal were marked with pins from the exterior. These were actually the expected positions of the commisures as per the standard texts. Now visualizing from the atrial aspect these junctional areas were marked with a coloured marker onto the leaflet surface. This was intended to identify and delineate the leaflet portion abutting the respective wall of the ventricle and also to ascertain whether the major commisures complied to the expected positions.

Annular attachment of the leaflets was ascertained by palpating the annular ring from the atrial side. The attached margin of the valve leaflets was cut along the annular ring. The papillary muscles were cut at their bases to remove the valve leaflets along with chordae tendinae and papillary muscles. The valve leaflets were then cut at the junction of septal and anterior wall so as to spread it open for further study. It was spread over a white thermacol sheet and the atrial side of the leaflets facing the observer. It was then opposed to a transparent glass plate. The annular margin and free margin of the leaflets were marked with a marker pen over the glass plate and subsequently transferred over a translucent butter paper. Following observations were recorded from each tricuspid valve tracing.

(1) Number of commissures and their positions: the commissures were defined as major and minor based on following criteria—commissures are any indentation in the free margin of the valve.

- Major commissures: indentation more than 2/3 of maximum height of the larger of the two adjacent leaflets in question.

- Minor commissures: indentation between 1/3 to 2/3 of maximum height of the larger of the two adjacent leaflets in question.

- Indentations less than 1/3 of the maximum height of the larger of the two adjacent leaflets in question were disregarded.

(2) The number and position of major commissures was noted. The number and position of leaflets was also noted. A leaflet was defined as part of valve situated between two major commissures.

(3) Number and position of minor commissures in each leaflet was also observed. A scallop was defined as a part of leaflet separated out from the main leaflet by a minor commissure.

The above criterion was devised for objective classification of major and minor commissures, leaflets, and scallops. It is assumed that the functional independence of the adjacent leaflets is attained by virtue of depth of indentations along its margins.

Results

Following observations were made based on the newly defined criteria.

Number of major commissures

Variable numbers of major commissures were observed ranging from one to three. Accordingly the number of leaflets also varied from one to three.

Position of major commissures

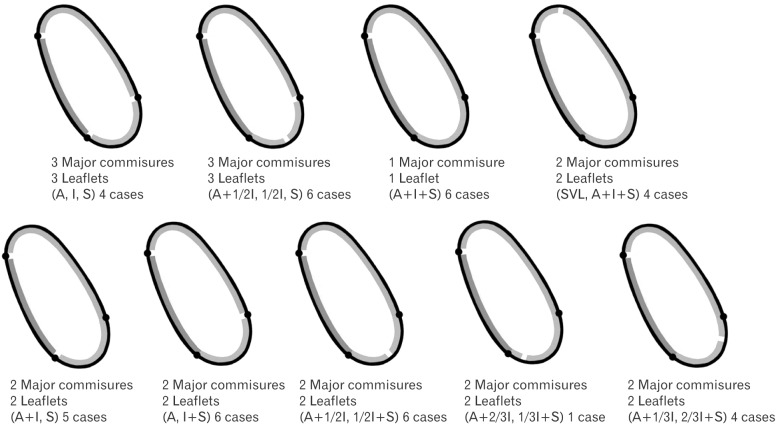

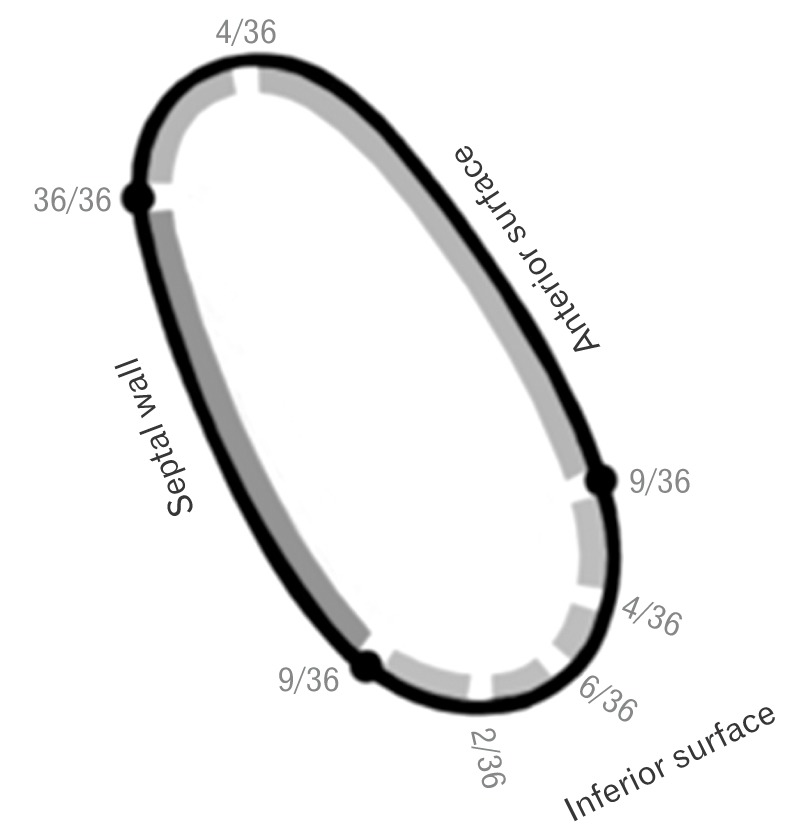

Fig. 1 shows the position and frequency of major commissures. A constant major commissure was observed in all hearts at the junction of septal and anterior walls. This commissure was characterized by a deep indentation that reached close to the annulus.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram showing position of major commissural zone along with their frequency along the annular circumference. Gaps represent the site of commissural zone and thickened continuous areas denote the leaflets. Black dots represent conventional positions (at the junction of different surfaces of the ventricular wall) of commissures.

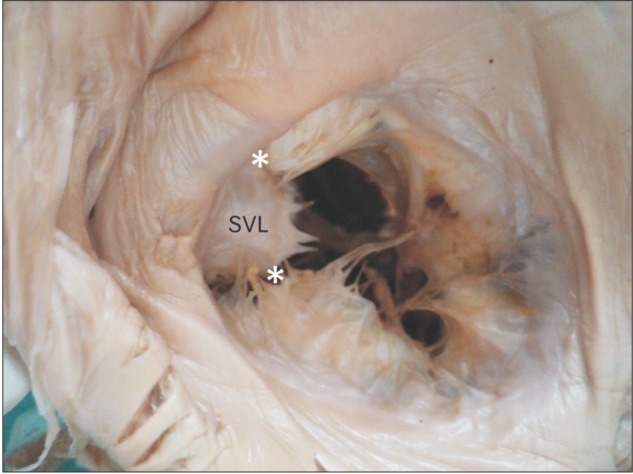

In four cases, the major commissure appeared in left corner of anterior wall separating out a small leaflet between the constant commissure and itself. This small leaflet was seen abutting supraventricular crest inferiorly (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Supraventricular leaflet (SVL) overlying the supraventricular crest between the two major commissures (asterisks).

Other major commissures, when present, were mostly observed on the inferior wall either at its margin or somewhere in between. Consequently, it was observed that inferior leaflet displayed variations ranging from it being an independent leaflet to getting apportioned with anterior or septal leaflet completely or partially.

Major commissures other than the constant one were generally not so deep so as to reach the annular margin.

Number of leaflets

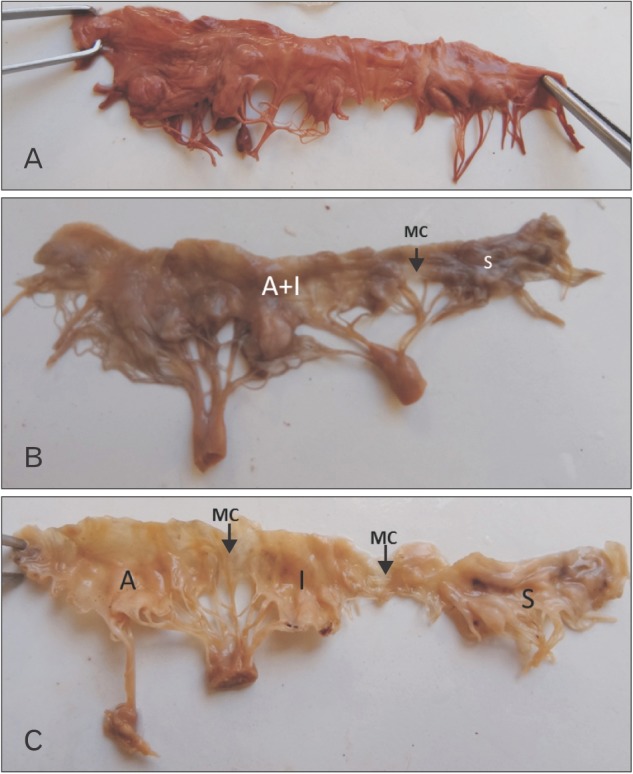

Single leaflet were observed in six cases, double in 26 cases and triple in four cases (Figs. 3A–C, 4).

Fig. 3. Single (with wide unindented basal zone) (A), double (B), and three (C) leaflets. The valve has been cut open at the constant major commissure. MC, major commissure; A, anterior leaflet; I, inferior leaflet; S, septal leaflet; A+I, anterior has completely accrued the inferior leaflet.

Fig. 4. Schematic diagram depicting the pattern, characterization and number of leaflets and major commissures in the hearts studied. Gaps represent the site of major commissural zone and thickened continuous areas denote the leaflets. A, anterior leaflet; I, inferior leaflet; S, septal leaflet; SVL, supraventricular leaflet.

One major commissure: one leaflet

In six hearts, only a single major commissure was observed at the junction of anterior and septal wall. The single leaflet observed in these hearts had a wide basal zone continuous across the valve surface, uninterrupted by any major commissure, showing minimal indentations in free margin (Figs. 3A, 4).

Three major commissures: three leaflets

Three major commissures positioned at junctions of respective ventricular walls were separating three leaflets, complying the standard description, were observed in three hearts (Figs. 3C, 4). In one heart, the three leaflets were of the composition: anterior+1/2 inferior, 1/2 inferior, septal.

Two major commissures: two leaflets

In cases of two major commissures when present; one was constant at septal-anterior wall junction and the second major commissure was found to be variable separating out different patterns of leaflets depending upon its position (Figs. 3B, 4).

Characterization of leaflets

Depending on the number and position of the major and minor commissures, the pattern of leaflets and their characterization is depicted in Table 1 and Fig. 4.

Table 1. Pattern and characterization of valve leaflets.

| Leaflet | Pattern | Characterization | Frequency of occurrence (case) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior | Anterior (9 cases) | 1 Scallop | 6 |

| 2 Scallops | 2 | ||

| 3 Scallops | 1 | ||

| Anterior with one-third posterior (4 cases) | 2 Scallops | 3 | |

| 3 Scallops | 1 | ||

| Anterior with one-half posterior (7 cases) | 1 Scallops | 1 | |

| 2 Scallops | 5 | ||

| 4 Scallops | 1 | ||

| Anterior with two-third posterior (1 case) | 2 Scallops | 1 | |

| Anterior with complete posterior (5 cases) | 2 Scallops | 1 | |

| 3 Scallops | 4 | ||

| Posterior | Posterior (3 cases) | 1 Scallop with plateau | 2 |

| 2 Scallops | 1 | ||

| One-half posterior (1 case) | 1 Scallop | 1 | |

| Septal | Septal (9 cases) | 1 Scallop | 5 |

| 1 Scallop+1 plateau | 2 | ||

| Plateau on sides with scallop | 1 | ||

| 1 Plateau | 1 | ||

| Septal with one-third posterior (1 case) | 1 Scallop+1 plateau | 1 | |

| Septal with one-half posterior (6 cases) | 1 Scallop | 1 | |

| 2 Scallops | 1 | ||

| 1 Plateau | 1 | ||

| Septal with two-third posterior (4 cases) | 2 Scallops | 2 | |

| 1 Plateau | 1 | ||

| Septal with complete posterior (6 cases) | 2 Scallops | 2 | |

| 3 Scallops | 3 | ||

| 1 Scallop+1 plateau | 1 |

Anterior leaflet

It was separate in nine hearts; in 17 hearts, the position of major commissure was such that either complete or part of inferior leaflet was apportioned with anterior leaflet.

Inferior leaflet

In three cases, major commissure were positioned at the margins of inferior surface separating out an independent inferior leaflet. In 12 cases, posterior leaflet was split to be apportioned with adjacent leaflets. In six cases, it merged with entirely with septal leaflet; in five cases, it merged entirely with anterior (Fig. 3).

Septal leaflet

The septal leaflet was more often in the form of the plateau with shorter peaks. It was independent in nine cases with two major commissures positioned at the margins of septal wall. In 17 cases, it was apportioned with inferior leaflet.

Minor commisures and wide basal zone

Besides the regions of major commissures which were relatively deeper indentations in the valve margin, other indentations were shallower classified as minor commisures—separating out scallops, in the present study. The tendency to form scallops increased as increasingly larger portions of inferior leaflet were accrued either by anterior or septal leaflets. The larger leaflets, having a wider annular attachment showed multiple scallops and wide basal zone (unindented basal part of the leaflet) (Fig. 3A).

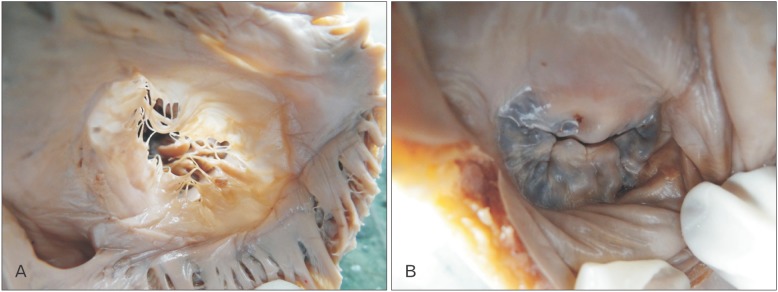

Coaptation of leaflets

An appreciable difference in coaptation of leaflets was also observed between mitral and tricuspid. While mitral leaflets exhibited a perfect congruence and coaptation, the tricuspid valve leaflets appeared to be poorly congruent showing minimal coaptation (Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 5. Difference in coaptation of leaflets between tricuspid and mitral valve. (A) Poorly congruent tricuspid with minimum coaptation. (B) Perfectly congruent and coapted mitral valve.

Discussion

Though conventionally considered to be tricuspid, some authors have questioned the trifoliate arrangement of this valve [4,5,6,7,8]. While Victor and Nayak [5] have proposed a bicuspid model, Skwarek et al. [7] have proposed a quadricuspid model. Victor and Nayak's [5] assumption of tricuspid valve to be bicuspid appears to be oversimplification of a highly variable valve. They have described the valve to have a mural leaflet and a septal leaflet; however, they have not accounted for the commissures which separate these leaflets and/or also extra commissures when present.

Joudinaud et al. [6] assumed the valve to be tricuspid and essentially having three cusps. All the extra cuspal tissue of smaller height was described by them as commissural leaflets and their basal attachment was considered to be a commissure. While doing so they inadvertently described very wide commissural areas having up to four leaflets. They also did not consider the presence of scallops in single leaflet.

The newly defined criteria to describe commissure and leaflet helped us to overcome the variability. The present study thus clearly defined the number and position of major commissures and the leaflets hence helped to count and characterize the leaflets.

The present study while utilizing the newer criteria also utilized the conventional terminology of leaflets and has tried to document the variability in terms of accepted nomenclature.

The tendency to form scallops increased as the anterior/septal leaflets accrued increasingly larger portions of posterior leaflet. This was probably to ensure mobility of leaflet which otherwise would be compromised because of longer inter commissural length.

The wide basal zone as observed in all cases across the bases of leaflets appears to be a potential hindrance to the mobility of leaflets. This fact has not been described in available literature. This is different from mitral valve where deep commissures delineate the leaflets and is also evidence that the functional dynamics of tricuspid valve are very different from that of mitral. Authors believe that this wide basal zone inhibits the mobility of valve leaflets thus compromising the opening of tricuspid orifice.

The seemingly incongruent poorly coapted leaflets of tricuspid valve as observed in the present study might be a predisposing factor for regurgitation during ventricular systole. Support to this hypothesis comes from the observations of studies [12,13,14] by documenting trivial to mild tricuspid regurgitation on Doppler echo in 80%–90% of normal subjects. Fukuda et al. [15] have stated that tricuspid annular circumference and area are all larger than that of mitral annulus by 20%; however, during atrial systole, the tricuspid annulus displays 19% reduction in annular circumference and 30% reduction in annular area. This mechanism might aid the closure of valve orifice in otherwise incongruent and malcoapted leaflets.

The study concludes that the tricuspid valve is rarely tricuspid. It also generates following hypothesis.

(1) The tricuspid valve does not open completely due to presence of a wide basal zone.

(2) Tricuspid valve does not close completely owing to incongruence and lack of coaptation of leaflets.

These hypotheses warrant further studies for confirmation.

References

- 1.Hollinshead WH. Anatomy for surgeons. Vol. 2. The thorax, abdomen and pelvis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1971. p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Standring S. Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice. 39th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. pp. 1163–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinnatamby CS. Last's anatomy: regional and applied. 10th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2001. p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutton JP, 3rd, Ho SY, Vogel M, Anderson RH. Is the morphologically right atrioventricular valve tricuspid? J Heart Valve Dis. 1995;4:571–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Victor S, Nayak VM. The tricuspid valve is bicuspid. J Heart Valve Dis. 1994;3:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joudinaud TM, Flecher EM, Duran CM. Functional terminology for the tricuspid valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2006;15:382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skwarek M, Hreczecha J, Dudziak M, Jerzemowski J, Wilk B, Grzybiak M. The morphometry of the accessory leaflets of the tricuspid valve in a four cuspidal model. Folia Morphol (Warsz) 2007;66:323–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lama P, Tamang BK, Kulkarni J. Morphometry and aberrant morphology of the adult human tricuspid valve leaflets. Anat Sci Int. 2016;91:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusted IE, Scheifley CH, Edwards JE, Kirklin JW. Guides to the commissures in operations upon the mitral valve. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1951;26:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranganathan N, Lam JH, Wigle ED, Silver MD. Morphology of the human mitral valve. II. The value leaflets. Circulation. 1970;41:459–467. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver MD, Lam JH, Ranganathan N, Wigle ED. Morphology of the human tricuspid valve. Circulation. 1971;43:333–348. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein AL, Burstow DJ, Tajik AJ, Zachariah PK, Taliercio CP, Taylor CL, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Age-related prevalence of valvular regurgitation in normal subjects: a comprehensive color flow examination of 118 volunteers. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1990;3:54–63. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80299-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rogers JH, Bolling SF. The tricuspid valve: current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119:2718–2725. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, Larson MG, Freed LA, Fuller DL, Lehman B, Benjamin EJ. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)01064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuda S, Saracino G, Matsumura Y, Daimon M, Tran H, Greenberg NL, Hozumi T, Yoshikawa J, Thomas JD, Shiota T. Three-dimensional geometry of the tricuspid annulus in healthy subjects and in patients with functional tricuspid regurgitation: a real-time, 3-dimensional echocardiographic study. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I492–I498. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]