Abstract

Incisional hernia remains a very common postoperative complication. These are encountered with an incidence of up to 20 % following laparotomy. These hernias enlarge over time, making the repair difficult, and serious complications like bowel obstruction, strangulation and enterocutaneous fistula can occur. Hence, elective repair is indicated to avoid these complications. Implantation of a prosthetic mesh is nowadays considered as the standard treatment due to low hernia recurrence. The most common mesh repair techniques used are the onlay repair, sublay repair and laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM). However, it is still not clear which technique among the three is superior. A study consisting of 30 patients who underwent incisional hernia repair by onlay, laparoscopic and preperitoneal mesh repair with abdominoplasty was conducted in the Coimbatore Medical College and Hospital. Of the three groups, the preperitoneal repair with abdominoplasty was found to have better patient compliance and satisfaction with regard to occurrence of complications and appearance of the abdominal wall without laxity in a single sitting.

Keywords: Preperitoneal mesh repair, Laparoscopic IPOM, Onlay mesh repair, Incisional hernia

Background

Incisional hernia remains a very common postoperative complication. These are encountered with an incidence of up to 20 % following laparotomy [1]. These hernias enlarge over time, making the repair difficult, and serious complications like bowel obstruction, strangulation and enterocutaneous fistula can occur. Hence, elective repair is indicated to avoid these complications. The recurrence rates after suture repair are as high as 58 % [2]. Implantation of a prosthetic mesh is nowadays considered as the standard treatment due to low hernia recurrence. The lower recurrence rate in mesh repair is somewhat flawed by a slightly increased wound infection rate. Surgical repair of incisional and ventral hernias includes the type and technique of repair if prosthetic mesh is to be used. The use of mesh for abdominal wall reconstruction has significantly reduced hernia recurrence as compared to primary repair. The most common mesh repair techniques used are the onlay repair, sublay repair and laparoscopic intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM). However, it is still not clear which technique among the three is superior.

Study Objective

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate prospectively the early and late postoperative complication of three different techniques in repair of incisional hernia: onlay repair, preperitoneal repair and laparoscopic IPOM.

Methods and Materials

This study was designed as a prospective, double-blind, randomised study on patients undergoing incisional hernia mesh repair. Inclusion criteria were the following: age ≥18 years and incisional hernia requiring surgical repair of size ≥4 cm. Exclusion criteria included previous mesh repair at the same site, acute incarcerated hernia, infected hernia, evidence of contaminated or clean-contaminated fields and additional surgical treatment at the same time. Written informed consent was taken from all participating patients.

The patients fulfiling the above criteria were randomised into three groups: first group undergoing onlay repair, second group preperitoneal repair and third group laparoscopic IPOM. Demographic, preoperative, operative, perioperative, postoperative and follow-up data were collected from each of the patients in the study.

Adverse events in this study were defined as any undesirable clinical events occurring in abdominal wall involving abdominal organs in the postoperative period. These adverse effects were classified into mild, moderate or severe based on intensity experienced by the subject. Mild events included awareness of a sign or symptom that does not interfere with the subject’s activity and is resolved without treatment or sequelae. Moderate events may interfere with the subject’s activity and require additional treatment or intervention, while severe events definitely cause significant discomfort to the subject and require additional treatment with additional sequelae.

Intraoperative parameters include operative time and blood loss. Perioperative adverse events occurred within 14 days of hernia repair. Early postoperative events occurred between 15 days and 6 months of hernia repair. Late postoperative adverse events occurred greater than 6 months after hernia surgery. These include seroma collection, increased drain, wound infection, mesh feeling, mesh rejection, sinus formation, recurrence of hernia and mesh migration.

Patient follow-up in postoperative visits was undertaken on the following time points: 2 weeks, 2 months and 6 months with specific days on which he/she was to report for follow-up. At each follow-up visit, an interim history and a physical exam were performed by the operating surgeon or a designated assistant.

To assess the quality of life after surgery, the Carolinas Comfort Scale (CCF) was used. The CCS is a 23-item, Likert-type questionnaire that measures severity of pain, sensation and movement limitations from the mesh in the following eight categories: laying down (LD), bending over (BO), sitting up (SU), activities of daily living (ADLs), coughing or deep breathing (CB), walking (W), stairs (S) and exercise (E). The CCS score is derived by adding the scores from each of the 23 items. The best possible score is 0, and the worst possible score is 115.

Surgical Procedure

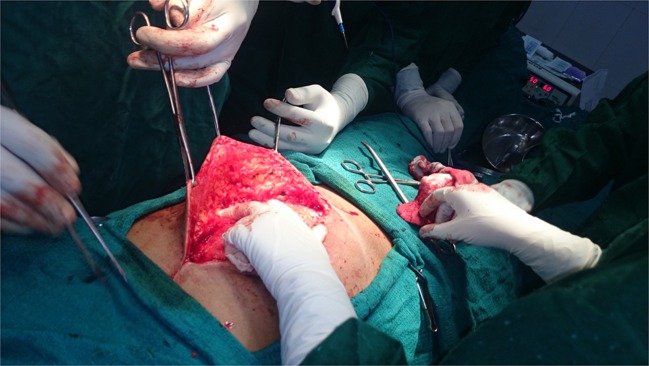

To assure comparability and minimise operator bias, the procedure and perioperative treatment were strictly standardised. The operation was initiated as a vertical median incision. In onlay repair, the hernia sac was identified, skin flaps were raised all around and the midline rectus wall defect was closed primarily. A mesh was placed anteriorly to the closed rectus defect with an overlap of 5 cm of the abdominal wall defect in each direction [3]. In preperitoneal repair, a space was created between both the posterior rectus sheaths and the peritoneum (Fig. 1). The peritoneum was closed with a running non-absorbable suture. The mesh was placed in position between the posterior rectal sheath and the peritoneum. Mesh was fixed by single knots every 3 cm using monofilament non-absorbable sutures with a 5-cm overlap in each direction of the abdominal wall defect. The anterior rectus sheath was closed using a continuous running monofilament non-absorbable suture with a ratio of 4:1 between the suture length and the incision length. Two suction drains were kept: one in the mesh bed and other in the subcutaneous plane.

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative picture of preperitoneal repair

In laparoscopic IPOM, a small incision was first made in the scar-free abdominal wall, laparoscopic camera and instruments were introduced, any adhesions were detached and then the contents of the hernial sac were exposed. Once the hernia opening was fully exposed, a mesh fitted with several sutures was introduced and unfolded over the defect with an overlap of 5 cm using a special instrument and the exposed double threads were guided out via tiny skin punctures through the abdominal wall and knotted via the small skin punctures to the abdominal wall fascia. For very big defects measuring more than 8 cm, the defect was first closed with a suture to provide greater support to the mesh.

Mesh

We used a polypropylene mesh with a size of 15 × 15 cm, weight of 80–85 g/m2, thickness of 0.6 mm, pore size of 1–2 mm and tension strength of 8 % at 16 N/cm. The mesh was used for all the three hernia repairs. For laparoscopic repair, a composite mesh was used.

Results

Between July 2013 and August 2014, 50 patients with incisional hernia were screened for the study. As shown in Table 1, 20 patients were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thirty patients were randomised and included in the study. Eighteen patients were women and 13 were men, and the mean age was 56.3 years (28–75). Thirteen patients underwent onlay mesh repair, 11 patients underwent preperitoneal repair and 6 patients underwent laparoscopic IPOM.

Table 1.

Adverse events in the study

| Onlay repair (n = 13) | Preperitoneal repair (n = 11) | Laparoscopic IPOM (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative (<14 days) | |||

| Days of retained drain | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Seroma | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Wound infection | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Peritonitis | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Early postoperative (15 days–6 months) | |||

| Seroma | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sinus formation | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Mesh rejection | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrence of hernia | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Late postoperative (>6 months) | |||

| Sinus formation | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Mesh rejection | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Mesh migration | 1 | 0 | Not available |

| Recurrence of hernia | 1 | 0 | Not available |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | 0 | 0 | 0 |

In the perioperative period, seroma collection occurred in 38.5 % of the patients undergoing onlay repair. The number of days of retained drain was observed to be longest in the onlay group. Wound infection in 16.7 % of the patients occurred equally among all the groups.

Sinus formation was the most common early postoperative period, which occurred in 46 and 9 % of the patients in onlay and preperitoneal groups, respectively. A single case of Prolene sinus formation was seen in the preperitoneal group which subsided with antibiotic treatment.

Adverse effects were rarely observed in the late postoperative period with only two Prolene sinus formations and one mesh rejection being observed in the onlay group. A single case of recurrence of hernia was observed in the onlay repair group during the 7th month of follow-up. There were no late postoperative complications in preperitoneal repair.

The Carolinas Comfort Scale score survey was completed satisfactorily (Table 2). The included study patients (30 in number) completed the questionnaire at end of the 2nd week. Only 27 patients completed the survey at the end of the 2nd and 6th months. The results of the symptoms for each activity in areas of mesh sensation, pain and movement limitation were observed. These scores were observed to decline gradually over a period of 6 months.

Table 2.

Carolinas Comfort Scale (CCF) mean values of score in the study

| Time of postoperative follow-up | Onlay repair (n = 13) | Preperitoneal repair (n = 11) | Laparoscopic IPOM (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carolinas Comfort Scale (CCF) mean (score range 0–115) | 2nd week | 40 | 45 | 35 |

| 2nd month | 35 | 30 | 32 | |

| 6th month | 20 | 15 | 30 |

The majority (74 %) of the patients undergoing any repair technique returned to normal daily routine activity within 2 weeks. At the end of 4 weeks, all were able to do their routine activity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Duration to return to various activities in the study

| Duration to return to activity | Onlay repair (n = 13) | Preperitoneal repair (n = 11) | Laparoscopic IPOM (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration to return to normal, daily activity | |||

| <2 weeks | 8 | 9 | 4 |

| 2–4 weeks | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| 4–8 weeks | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Duration to return to more vigorous or strenuous activity | |||

| <3 weeks | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 3–7 weeks | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| 7–11 weeks | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| >11 weeks | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Not applicable | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Patient’s physical job requirements | |||

| Minimal physical requirements | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Moderate physical requirements | 6 | 6 | 1 |

| Heavy physical requirements | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Not employed | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Patients undergoing preperitoneal repair (100 %) were able to perform vigorous or strenuous activity earlier compared to those who underwent an onlay repair (87 %) at the end of 11 weeks.

Discussion

The standard procedure for incisional hernia is implantation of prosthetic mesh. Various studies have concluded that mesh repair is superior to suture repair which has 85 % higher recurrence risk compared to mesh repair [4–6]. This can be done using various techniques like onlay mesh repair, sublay mesh repair and laparoscopic mesh repair.

The onlay technique involves primary closure of the fascial defect and subsequent reinforcement by placing the prosthetic mesh on top of the fascial repair and securing the mesh to anterior rectus sheath with sutures or facial staplers. The major advantage is that the mesh is separated well away from the intra-abdominal contents reducing complications. This technique has several disadvantages like extensive dissection of subcutaneous plane which leads to seroma collection, mesh infection in superficial wound breakdown, primary repair under tension and, hence, the presence of a more risk of recurrence.

The sublay technique includes the placement of prosthetic mesh being placed intraperitoneally or preperitoneally in the recto-rectus submucosal space. This preperitoneal technique has less recurrence rate and postoperative wound complications as supported by a study from a randomised, controlled trial which showed that onlay technique was associated with five times higher recurrence rates (10.5 vs. 2 %) and twice the rate of postoperative wound complications (49.1 vs. 24 %) when compared with placing the mesh in an underlay fashion [4, 6]. The preperitoneal mesh placement repair gives an opportunity for excision of the previous scar in the repair, a cosmetic placement of the surgical scar such as transverse elliptical or Pfannenstiel incision. Lax abdominal wall can be managed at the same time of surgery by judicious excision of skin, lipectomy and subcuticular closure. The dangers of peritonitis are practically nil.

Laparoscopic IPOM repair involves trained surgeons, expensive equipments and a long-learning curve. The advantages are short duration of postoperative period and early return to work. While the hernia is repaired with mesh, the abdominal wall is not repaired and continues to be lax. The cosmetic effect of a pendulous and lax abdominal wall cannot be overemphasised. Some patients require other surgical procedures to improve abdominal cosmesis. The potential danger of bowel injuries due to electrocautery going unnoticed leading to faecal peritonitis is formidable.

One case of recurrence in the onlay group without any recurrence in preperitoneal repair and laparoscopic IPOM was observed. Wound infection was observed to be 53.8 % in the onlay group, 27.8 % in the preperitoneal group and 33.4 % in the laparoscopic IPOM group. Peritonitis when occurred was managed by re-exploration and laparotomy.

Sinus formation in the postoperative period was observed to occur in 61 % at the end of 6 months with three cases of mesh rejection and one case of mesh exposure in the onlay group. The preperitoneal repair group had one case of sinus formation only.

Conclusion

A study consisting of 30 patients who underwent incisional hernia repair by onlay, laparoscopic and preperitoneal mesh repair with abdominoplasty was conducted in the Coimbatore Medical College and Hospital. Of the three groups, the preperitoneal repair with abdominoplasty was found to have better patient compliance and satisfaction with regard to occurrence of complications and appearance of the abdominal wall without laxity in a single sitting. The preperitoneal repair procedure can easily be performed by a surgeon by proper guidance and has a short learning curve.

The economic aspects of the treatment of complications, cost of composite mesh and need for plastic surgery later especially in young and middle-aged women have to be taken into consideration. More studies in this regard are needed as the learning curve among operating surgeons progresses.

Contributor Information

S. Natarajan, Phone: 9443013402, Email: swaminatarajan2003@gmail.com

S. Meenaa, Phone: 9442127238, Email: drsmeenaa@gmail.com

K. A. Thimmaiah, Phone: 8870736474, Email: deshthim@gmail.com

References

- 1.Mudge M, Hughes LE. Incisional hernia: a 10 year prospective study of incidence and attitudes. Br J Surg. 1985;72:70–71. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800720127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Read RC, Yoder G. Recent trends in the management of incisional herniation. Arch Surg. 1989;124:485–488. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1989.01410040095022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Den Hartog D, Dur AH, Tuinebreijer WE, et al (2008) Open surgical procedures for incisional hernias. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD006438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.de Vries Reilingh TS, van Geldere D, Langenhorst B, de Jong D, et al. Repair of large midline incisional hernias with polypropylene mesh comparison of three operative techniques. Hernia. 2004;8(1):56–59. doi: 10.1007/s10029-003-0170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kurzer M, Kark A, Selouk S, Belsham P, et al. Open mesh repair of incisional hernia using a sublay technique: long-term follow-up. World J Surg. 2008;32(1):31–36. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.'Wéber G, Baracs J, Horváth OP, et al. Onlay mesh provides significantly better results than sublay reconstruction. Prospective randomized multicenter study of abdominal wall reconstruction with sutures only, or with surgical mesh—results of a five-year follow-up [DOI] [PubMed]