Abstract

One unique feature of the shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) genome is the presence of a giant open reading frame (ORF) of 18,234 nucleotides that encodes a long polypeptide of 6,077 amino acids with a hitherto unknown function. In the present study, by applying proteomic methodology to analyze the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis profile of purified WSSV virions by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), we found that this giant polypeptide, designated VP664, is one of the viral structural proteins. The existence of the corresponding 18-kb transcript was confirmed by sequencing analysis of reverse transcription-PCR products, which also showed that vp664 was intron-less. A time course analysis showed that this transcript was actively transcribed at the late stage, suggesting that this gene product should contribute primarily to the assembly and morphogenesis of the virion. Several polyclonal antisera against this giant protein were prepared, and one of them was successfully used for immunoelectron microscopy analysis to localize the protein in the virion. Immunoelectron microscopy with a gold-labeled secondary antibody showed that the gold particles were regularly distributed around the periphery of the nucleocapsid with a periodicity that matched the characteristic stacked ring subunits that appear as striations. From this and other evidence, we argue that this giant ORF in fact encodes the major WSSV nucleocapsid protein.

White spot syndrome virus (WSSV) is one of the most devastating shrimp pathogens, and it has caused serious damage to the worldwide shrimp culture industry. Although this virus can infect several crustacean species, including shrimp, crab, and crayfish (9, 12, 19, 24, 42), its virulence is particularly high in infected penaeid shrimp, and mortality can reach 90 to 100% within 3 to 7 days of infection (9, 46). The WSSV virion is a nonoccluded, enveloped particle of approximately 275 by 120 nm with an olive-to-bacilliform shape, and it has a nucleocapsid (300 by 70 nm) with periodic striations perpendicular to the long axis (42, 43). The most prominent feature of WSSV is the presence of a tail-like extension at one end of the virion (10, 43), which gives this virus the family name Nimaviridae (27) (“nima” is Latin for “thread”).

The complete genome sequences of three WSSV isolates have been determined, and 532 open reading frames (ORFs) that contain >60 amino acids have been identified for the Taiwan isolate (GenBank accession number AF440570). Homology searches against the NCBInr database suggest possible roles or functions for only a few of these ORFs, and most of the ORFs posted for the Taiwan isolate show no significant similarity to other known proteins. Similar results have been reported for the other two isolates (40, 44). Until recently, <5% of the ORFs had been shown to encode either nonstructural proteins (ribonucleotide reductase, protein kinase, the chimeric thymidine kinase/thymidylate kinase, and DNA polymerase [8, 22, 35, 36]) or structural proteins (VP28, VP26, VP24, VP19, and VP15 [38, 39, 41, 47, 48, 49]). Recently, however, thanks to the introduction of proteomic methods, the total number of known viral structural proteins has increased to 39 (17, 18, 21, 34). Tsai et al. (34) also reported a protein that was much larger than the largest (220 kDa) marker protein, and by using liquid chromatography-nano-electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (LC-nano-ESI-MS/MS), they found that this corresponded to a giant ORF that encodes a long polypeptide of 6,077 amino acids with a theoretical mass of 664 kDa. In this paper, we further investigate the gene expression and function of this protein, designated VP664, and present evidence that it is associated with one of the unique features of the WSSV virion, i.e., the stacked ring subunits that appear as striations on the WSSV nucleocapsid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus.

The virus used for this study was isolated from a batch of WSSV-infected Penaeus monodon shrimp collected in Taiwan in 1994 (42) and is now known as the WSSV Taiwan isolate (25). The complete genome sequence (307,287 bp) of this isolate is available in GenBank under accession number AF440570.

Proliferation and purification of WSSV virions.

Gill and epithelial tissues from shrimp (Penaeus monodon; mean weight, 10 g) infected with the WSSV Taiwan isolate were homogenized in TNE buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1 M NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) at 0.25 g/ml. After centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was filtered (0.45-μm-pore-size filter) and injected (0.2 ml; 1:10 dilution in TNE) intramuscularly into healthy Procambarus clarkii crayfish. After propagation of the virus in the crayfish for 4 to 6 days, the virions in the hemolymph were purified as described previously (34). (Procambarus clarkii was a convenient host for this study because it can sustain a heavy WSSV viral load indefinitely, whereas in Penaeus monodon, once virus replication is triggered, the disease progresses along a fixed course and ends in mortality in just a few days.)

Mass analysis.

Identification of the WSSV structural protein by LC-nano-ESI-MS/MS was performed as described previously (34).

Antibody preparation.

PCR fragments representing six different coding regions of vp664 were amplified by use of the primer sets listed in Table 1, digested with restriction enzymes, and cloned into pET-28b(+). The resulting pET clones were transformed into BL21 Codon Plus Escherichia coli cells (Stratagene). For protein expression and purification, the cells were grown overnight at 37°C in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 50 μg of kanamycin/ml and 34 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. The cells were inoculated into new medium at a ratio of 1:300 and grown at 37°C for 1.5 to 2 h. Expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), and incubation was continued for another 1.5 to 3 h. The induced bacteria were spun down at 4°C, suspended in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 10% glycerol and a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche Molecular Biochemicals), and sonicated for 30 s on ice. The insoluble debris was collected by centrifugation, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1.5% sodium lauryl sarcosine, and solubilized by shaking at 4°C for 2 h. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation and mixed with Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose beads on a rotating wheel at 4°C for 16 h or overnight. The beads were then washed several times with ice-cold wash buffer (1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) to remove unbound material. The fusion proteins were eluted directly from the beads with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and then were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. The protein bands containing the fusion proteins were sliced from the gel, minced, mixed with Freund's adjuvant, and used for antibody production.

TABLE 1.

Primer sets for amplicons used to generate recombinant proteins for antibody production

| Antibody | Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Location (positions) | Size (bp) of PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 664-1 | WSSV419-1.NdelF | CCATATGGACCAGTACCCAGAAG | 1-19 | |

| WSSV419-1.Xhol R | CCTCGAGTTAGGCTGCTCTAGCCTGTTC | 937-954 | 954 | |

| 664-8 | WSSV419-8.SalIF | ATGTCGACATGACCTCCGCTTTGAC | 8161-8177 | |

| WSSV419-8.Xhol R | ATCTCGAGGTCCATCACGATAGTGC | 9101-9117 | 957 | |

| 664-9 | WSSV419-9.Ndel F | CCATATGTCCGAGACACGCGCAGTCG | 9322-9340 | |

| WSSV419-9.Xhol R | CCTCGAGTTAAGCTTGATTATGAGACGC | 10261-10278 | 957 | |

| 664-10 | WSSV419-10.BamHI F | CCGGATCCTGTCAGGCTTAACCAGTACG | 10491-10510 | |

| WSSV419-10.Hind III R | CCAAGCTTTTAAACTGTCCCCGAGTTATCA | 11430-11450 | 960 | |

| 664-12 | WSSV419-12.SallF | ATGTCGACGCCATCATTTCTGGTATG | 12811-12831 | |

| WSSV419-12.XhoI R | ATCTCGAGATCCACAGCAGTATCGG | 13754-13770 | 960 | |

| 664-14 | WSSV419-14.BamHI F | CCGGATCCCAACTCTGGCATGACAACGG | 15179-15199 | |

| WSSV419-14 Hind III R | CCAAGCTTTTACAAATAGATGGCTACTTTCTC | 16117-16138 | 960 |

Underlining indicates the incorporated restriction enzyme sites at the 5′ ends of the primers.

Western blot analysis.

Purified virions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the separated proteins were then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (MSI). The membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin, 5% skim milk, 50 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with a polyclonal rabbit anti-VP664-1 antibody (1:5,000 dilution in blocking buffer, or as indicated in Results) for 1 h at room temperature. After the membrane was washed three times with TBS-T (0.1% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline), it was incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody diluted 5,000-fold in blocking buffer. The membrane was washed as described above, and proteins were visualized by use of a chemiluminescence reagent (Perkin-Elmer, Inc.).

Localization of WSSV VP664 by immunoelectron microscopy (IEM).

A purified WSSV virion suspension was adsorbed to Formvar-supported and carbon-coated nickel grids (150 mesh) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The primary antibody and preimmune rabbit serum were diluted 1:50 in incubation buffer (0.1% Aurion Basic-c, 15 mM NaN3, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The grids were blocked with blocking buffer (5% bovine serum albumin, 5% normal serum, 0.1% cold water skin gelatin, 10 mM phosphate buffer, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) for 15 min and then incubated with a diluted primary antibody or preimmune rabbit serum for 1 h at room temperature. After several washes with incubation buffer, the grids were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with 6- or 15-nm-diameter gold particles (1:40 dilution in incubation buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. The grids were then washed extensively with incubation buffer, washed twice more with distilled water to remove excess salt, and stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.2) for 30 s. Specimens were examined with a transmission electron microscope.

Time course analysis of vp664 by RT-PCR.

Since temporal WSSV gene expression has already been widely studied with Penaeus monodon (e.g., see references 7, 8, 22, 35, and 36), for a more direct comparison we continued to use Penaeus monodon in this study for a time course analysis of vp664 by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). Briefly, Penaeus monodon specimens were experimentally infected by intramuscular injection with WSSV and subsequently collected at the indicated times postinfection according to a procedure described by Tsai et al. (35). Total RNAs were isolated from the pleopods (swimming legs) of WSSV-infected shrimp or healthy shrimp by use of the TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen Corp.). The isolated RNAs (20 μg) were treated with DNase I (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) at 37°C for 1 h and then recovered by phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and ethanol precipitation. The total RNAs were reverse transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp.) and an oligo(dT) anchor primer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The first-strand cDNA products were subjected to PCRs with the primer set 5′-CGGCGCAACAACAACAAGCA-3′ and 5′-GTAGTTGGGGGCTAAACACG-3′ for WSSV vp664. The WSSV dna pol transcript was amplified with the primer set 5′-CCCCCGGGATGCTTCACTTTAATGAAAA-3′ and 5′-CCCCCGGGCTTTTTGTAAGGGGTGAAAG-3′. The WSSV vp28 transcript was amplified with the primer set 5′-ATCCTCGCCATCACTGCTGT-3′ and 5′-TTACTCGGTCTCAGTGCCAG-3′. The β-actin transcript was amplified with the primer set 5′-GAYGAYATGGAGAAGATCTGG-3′ and 5′-CCRGGGTACATGGTGGTGCC-3′ and was used as an internal control for RNA quality and amplification efficiency.

Full-length analysis of the 18-kb vp664 transcript by RT-PCR.

Total RNAs isolated from WSSV-infected shrimp at 36 h postinfection (hpi) were treated with DNase I, extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, and precipitated with ethanol. The total RNAs were primed with both an oligo(dT) anchor primer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) and a random primer (Promega) and were reverse transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp.). The first-strand cDNA products were subjected to PCRs with the 15 primer sets listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primer sets used for RT-PCR analysis

| Primer set | Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′)a | Location (positions) | Size (bp) of PCR product |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1/R2 | WSSV419-1.NdelF | CCATATGGACCAGTACCCAGAAG | 1-19 | |

| WSSV419-2 HindlII R | CCAAGCTTTAATACCCATACTGGGCATCA | 2106-2124 | 2,124 | |

| F2/R3 | WSSV419-2 BamHI F | CCGGATCCAGATTTTGAAGCATTGAGAGG | 1167-1187 | |

| WSSV419-3-R | AAAAGCTTTTAGGCGGACAAGGCATT | 3283-3298 | 2,132 | |

| F3/R4 | WSSV419-3-F1 | AAGGATCCAGGAGGAGGATATGAAATG | 2324-2343 | |

| WSSV419-4.XhoI R | ATCTCGAGCCATACCTTTGCAGGG | 4431-4446 | 2,123 | |

| F4/R5 | WSSV419-4.SalIF | ATGTCGACTATCTTAGGAGATATAGG | 3490-3507 | |

| WSSV419-5.Xhol R | CCTCGAGTTAAGAGCTCAGAGCTGCGTAG | 5589-5606 | 2,117 | |

| F5/R6 | WSSV419-5.Ndel F | CCATATGAACAACCGTTCATTCAATTTG | 4651-4671 | |

| WSSV419-6 HindIII R | CCAAGCTTTTAAATCATCATCATGAATCCTCC | 6748-6768 | 2,118 | |

| F6/R7 | WSSV419-6 BamHI F | CCGGATCCTGACTGCGCTAAAATCATGAA | 5811-5831 | |

| WSSV419-7-R | CTAAGCTTTTATTTGGCATCGGCCATC | 7935-7950 | 2,140 | |

| F7/R8 | WSSV419-7-F | AAGGATCCTACTGCCATTTACGGGTGC | 6969-6987 | |

| WSSV419-8.Xhol R | ATCTCGAGGTCCATCACGATAGTGC | 9101-9117 | 2,149 | |

| F8/R9 | WSSV419-8.SallF | ATGTCGACATGACCTCCGCT TTGAC | 8161-8177 | |

| WSSV419-9.Xhol R | CCTCGAGTTAAGCTTGATTATGAGACGC | 10261-10278 | 2,118 | |

| F9/R10 | WSSV419-9.NdelF | CCATATGTCCGAGACACGCGCAGTCG | 9322-9340 | |

| WSSV419-10 HindIII R | CCAAGCTTTTAAACTGTCCCCGAGTTATCA | 11430-11450 | 2,129 | |

| F10/R11 | WSSV419-10 BamHI F | CCGGATCCTGTCAGGCTTAACCAGTACG | 10491-10510 | |

| WSSV419-11-R | AGAAGCTTTTATCCTGGGCAGTTAAAC | 12624-12639 | 2,149 | |

| F11/R12 | WSSV419-11-F | TCGAATCCTGTGGAGAGGAGACAG | 11649-11664 | |

| WSSV419-12.XhoI R | ATCTCGAGATCCACAGCAGTATCGG | 13754-13770 | 2,122 | |

| F12/R13 | WSSV419-12.SallF | ATGTCGACGCCATCATTTCTGGTATG | 12811-12831 | |

| WSSV419-13.Xhol R | CCTCGAGTTAATGCTCGTTATCTGAGGG | 14932-14949 | 2,139 | |

| F13/R14 | WSSV419-13.Ndel F | CCATATGAACTCTTTCCTTCGTTCTTC | 13993-14012 | |

| WSSV419-14 HindIII R | CCAAGCTTTTACAAATAGATGGCTACTTTCTC | 16117-16138 | 2,146 | |

| F14/R15 | WSSV419-14 BamHI F | CCGGATCCCAACTCTGGCATGACAACGG | 15179-15199 | |

| WSSV419-15-R | ACAAGCTTTTACCTTCAGAGATGCCTG | 17285-17300 | 2,122 | |

| F15/R16 | WSSV419-15-F | CAGAATTCACAAATGGACCCCGAT | 16341-16356 | |

| WSSV419-16.Xhol R | ATCTCGAGCCGAAAATAAAGGCGGTT | 18211-18228 | 1,888 |

Underlining indicates the incorporated restriction enzyme sites at the 5′ ends of the primers.

5′ and 3′ RACE.

The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of vp664 were determined by use of a commercial 5′/3′ random amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) kit according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Total RNAs were isolated and treated with DNase I as described above. In the case of 3′ RACE, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized by use of an oligo(dT) anchor primer. The resulting cDNA was amplified with the specific forward primer 5′-CGCCTCAACCCCTACATC-3′ and the anchor primer. For 5′ RACE, the first-strand cDNA was synthesized with the vp664 gene-specific primer 1 (5′-TTCTGACGCAGCACGAAGAG-3′) and then purified by use of a High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche). The cDNA was given a 3′ tail of dTTPs by the use of terminal transferase and was subjected to a first round of PCR with an oligo(dA) anchor primer and the vp664 gene-specific primer 2 (5′-CTGAATCGTATGTGGTCGTGGA-3′). The PCR product was diluted and subjected to a second round of PCR with the anchor primer and the vp664 gene-specific primer 3 (5′-GATCCAGCACGAAGCTGCGATTG-3′). The final PCR products of 5′ and 3′ RACE were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) and then sequenced.

RESULTS

Identification of WSSV VP664 by mass spectrometry.

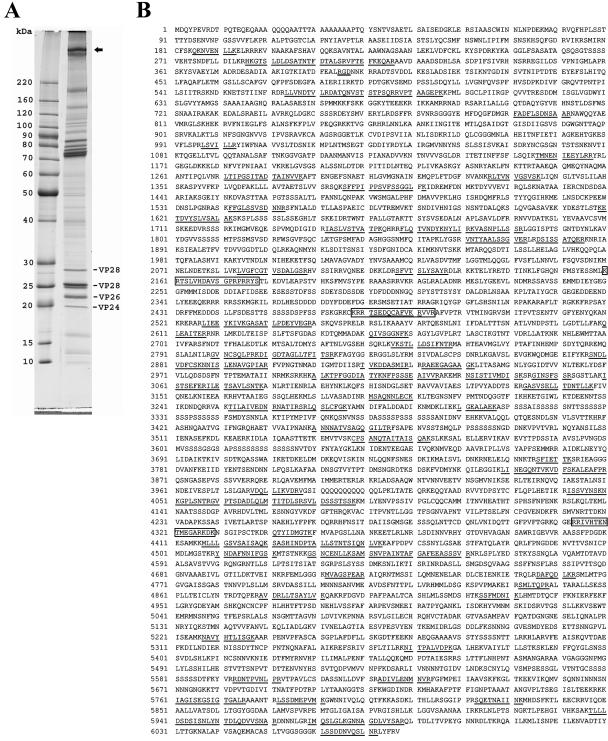

Figure 1A shows the protein profile of the WSSV virion, as analyzed by gradient SDS-PAGE (8 to 18% acrylamide). At least 34 discrete bands were identified. These protein bands were excised from the gel and subjected to trypsin digestion. The resulting peptides were then sequenced by LC-nano-ESI-MS/MS. The peptide sequences obtained from the MS/MS data were then analyzed against the NCBInr database by use of the Mascot server, and 33 protein bands were identified as containing WSSV-encoded peptides (31). The uppermost band in Fig. 1A (indicated with an arrow) contained peptide sequences encoded by vp664, with matching peptide sequences (Fig. 1B) that covered 14% of this giant protein. As shown in Fig. 1B, the matched sequences were evenly distributed along the entire protein, from the N terminus to the C terminus, which confirms the expression of the full 6,077 amino acids of this giant viral structural protein.

FIG. 1.

(A) SDS-PAGE profile of purified WSSV virion. The uppermost band (VP664; arrow) was excised from the gel and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. The peptide sequences suggested that this protein was the translated product of the vp664 ORF. Several other major structural proteins, VP28, VP26, and VP24, are also indicated. (B) Amino acid sequence of VP664. The peptide sequences identified by LC-MS/MS are indicated by underlining. Three bipartite nuclear targeting sequences are boxed. The RGD motif at positions 395 to 397 is indicated by double underlining.

Preparation of VP664-specific antibodies and Western blot analysis.

To further characterize this giant structural protein, we prepared antibodies against the coding region. A series of pET expression plasmids harboring different parts of the coding regions of the WSSV vp664 gene were constructed. The expressed proteins were purified, separated by SDS-PAGE, extracted from the gel, and injected into a rabbit to produce antibodies.

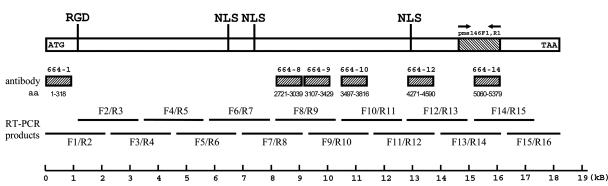

A total of six antibodies were produced (Table 1; Fig. 2). The antigenic specificity of each antibody was determined by Western blotting. Purified virions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, transferred onto a PVDF membrane, and probed with 5,000-fold-diluted antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3, a protein band with a relatively high molecular mass, far larger than the 180-kDa marker, was recognized by all six antibodies. The VP664-10 antibody also identified a minor protein band with a slightly lower molecular mass. A more complex pattern was produced by the VP664-1 antibody: in addition to a smear pattern in the upper part of the membrane blot, there were also about 20 other immunoreactive bands. We interpreted these as either degraded or C-terminally truncated VP664 proteins, in all of which the N-terminal region was presumably preserved intact. Decreasing the exposure time of the 664-1 blot revealed that the protein band with the strongest signal intensity was the same size as those recognized by the other antibodies (data not shown). Dilution of the 664-1 antibody (10,000-, 50,000-, and 100,000-fold) produced a similar result (Fig. 3B). The 664-1 antibody, which had a titer that was at least 10-fold higher than those of the other antibodies, was chosen for subsequent immunogold labeling analyses.

FIG. 2.

Schematic diagram showing the regions of VP664 used for antibody preparation and RT-PCR analysis. The separate shaded boxes represent the amino acid sequences corresponding to the recombinant proteins used for antibody production. The labeling of the RT-PCR products shows the primer sets that were used for amplification (Table 2). The locations of two structural features, the RGD motif and bipartite NLSs, are indicated on the protein, and the WSSV diagnostic PCR primer set developed by our laboratory, pms146F1 and pms146R1 (23), is also indicated.

FIG. 3.

Specificities of six VP664 antibodies as tested by Western blotting. (A) The purified virions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the separated viral proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane and probed with different antibodies diluted 5,000-fold. (B) Results of probing with the 664-1 antibody at higher dilutions (10,000, 50,000, and 100,000).

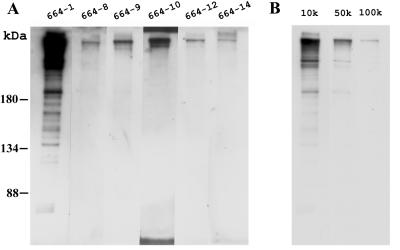

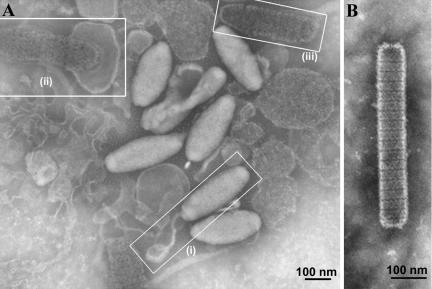

Localization of VP664 in the virion by IEM.

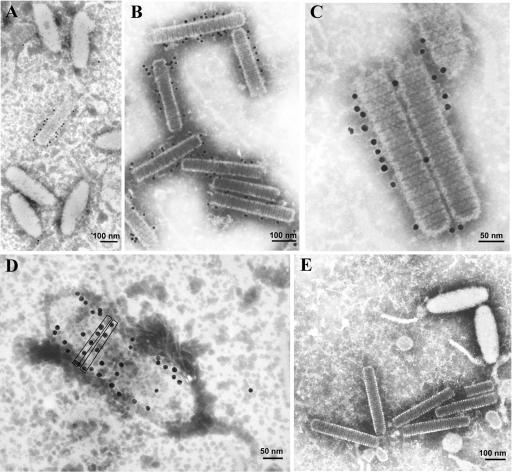

The localization of VP664 in the virions of WSSV was studied by IEM with the 664-1 antibody and a gold particle-conjugated secondary antibody. During the procedures for virus purification and immunoelectron microscopy, some viral envelopes spontaneously detached from their virions and released their nucleocapsids into the preparation. Figure 4A shows a WSSV preparation from Penaeus monodon (the WSSV isolate used to infect Penaeus monodon for Fig. 4 was the same Taiwan isolate that was used to infect the crayfish Procambarus clarkii in the other parts of this study) that very clearly illustrates this phenomenon, with examples of both entire and ruptured mature virions. Figure 4B, on the other hand, shows an example of an immature naked nucleocapsid, i.e., a nucleocapsid that has not yet become enveloped. Note that immature nucleocapsids can easily be distinguished from exposed mature nucleocapsids by their shape: immature nucleocapsids are thin and rod-shaped while mature nucleocapsids are fatter and rounder. These morphological observations apply to both Penaeus monodon and Procambarus clarkii. The IEM results for the crayfish preparations (Fig. 5) showed that the gold particles were almost all associated with the viral nucleocapsids, and no gold particles were found attached to the envelopes (Fig. 5A and B). The gold particles were often distributed quite regularly along the periphery of the nucleocapsids and were not confined to any specific regions (Fig. 5C). In these immature nucleocapsids, the periodicity of the gold particles also corresponded to the periodicity of the stacked ring-like structures. Occasionally, regularly spaced gold particles were also seen across the “top” of a mature nucleocapsid in a pattern that appeared to follow the periodicity of the stacked ring-like structures (Fig. 5D). These results strongly suggest that VP664 is a nucleocapsid—as opposed to an envelope—protein. In the negative control (Fig. 5E), the preimmune rabbit antiserum showed limited background cross-reactivity when tested against the WSSV virions and nucleocapsids.

FIG. 4.

Electron micrographs of purified virions. (A) The white outlines indicate (i) a complete mature virion with a characteristic tail, (ii) a ruptured mature virion with more than half of the nucleocapsid exposed outside of the envelope, and (iii) a completely exposed mature nucleocapsid. (B) Immature, naked nucleocapsid prior to being enveloped.

FIG. 5.

Immunoelectron microscopy analysis of purified virions probed with VP664 antibody. (A and B) The antibody specifically binds to the nucleocapsid and not to the viral envelope. (C) Most of the gold particles are localized to the perimeter of the nucleocapsid. (D) Occasionally, the gold particles are localized across the top of a nucleocapsid. (E) A preimmune rabbit antibody or gold-conjugated secondary antibody does not bind to virions.

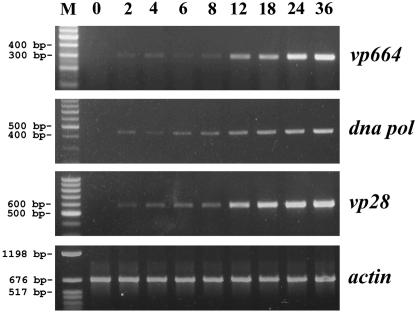

Time course analysis of vp664 transcript.

The expression profiles of the vp664 transcript in pleopods of adult Penaeus monodon shrimp at various stages of infection with WSSV were analyzed by RT-PCR. Two previously identified WSSV genes, dna polymerase (dna pol) and vp28, were also included in this assay for comparison. The results (Fig. 6) showed that a small amount of vp664 transcript could be detected as early as 2 hpi and that the expression level remained unchanged until 8 hpi. After that, the amount of vp664 transcript dramatically increased at 12 hpi and continued to increase until the end of the analysis. The dna pol gene, an early expressed gene, was transcribed as early as 2 hpi and steadily increased up to 36 hpi. The transcript of vp28, a gene that encodes a WSSV viral envelope protein, was also detected at 2 hpi, albeit at a low level, and like vp664, this low level of expression remained unchanged until 8 hpi. After that, the amount of vp28 transcript increased at 12 hpi and continued to increase until the end of the analysis. The expression kinetics of the vp664 transcript were thus quite similar to those of vp28: they were both highly expressed at the late stage and both translated into large amounts of viral structural proteins.

FIG. 6.

Time course analysis of vp664 transcripts by RT-PCR. Total RNAs were extracted from the pleopods of WSSV-infected shrimp and were subjected to RT-PCR analysis with the indicated primers, i.e., vp664, dna pol, and vp28. Shrimp actin was also included as a template control. Lane headings show times postinfection (hours). M, DNA marker.

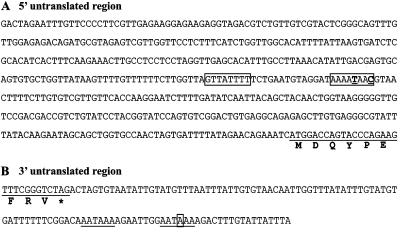

Mapping the 5′ and 3′ ends of the transcript by using RACE.

The 5′ and 3′ ends of the vp664 transcript were determined by the RACE method. Due to the presence of a long stretch of thymidines in the 5′ upstream region, the usual 5′ RACE protocol (22, 35) was modified slightly, as described in Materials and Methods. The RACE products were cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector, six clones were randomly chosen for sequencing, and the results are shown in Fig. 7. Two transcription initiation sites of the vp664 transcript were located 196 and 199 nucleotides upstream of the translational start codon (TAAC [initiation sites are shown in bold and underlined]). To identify possible motifs that are important for transcriptional regulation, we compared the 5′ upstream region of vp664 with the upstream regions of several structural protein genes, including vp28, vp26, vp24, vp19, and vp15 (26). A consensus sequence, AATAAC, was identified at the transcription initiation sites of both vp664 and another major structural protein gene, vp28, suggesting the importance of this consensus sequence in regulating the transcription of both of these highly expressed (Fig. 1A) late genes. (The major transcription initiation site of vp28 occurs at the C residue [26].) In vp664, the consensus sequence also formed part of an inverted repeat (boxed sequence in Fig. 7). Another sequence feature shared by both genes is the presence of a T track in the 5′ upstream region, although the importance of this T track remains to be determined. In the 3′ untranslated region, two polyadenylation signals (AATAAA) were found 73 and 90 bp downstream of the vp664 stop codon. 3′ RACE analysis showed that the poly(A) tail addition site was located 12 bp downstream of the first polyadenylation signal.

FIG. 7.

Partial nucleotide sequences of 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of vp664. (A) Sequencing results for six RT-PCR clones showed that there are two transcription initiation sites for vp664. The putative transcription initiation sites are shown in bold and underlined. The inverted repeats are boxed. (B) Underlining indicates the locations of two polyadenylation signals (AATAAA) downstream of the stop codon. The poly(A) addition site, as determined by 3′ RACE, occurs 12 bp downstream of the first polyadenylation signal and is indicated by a box.

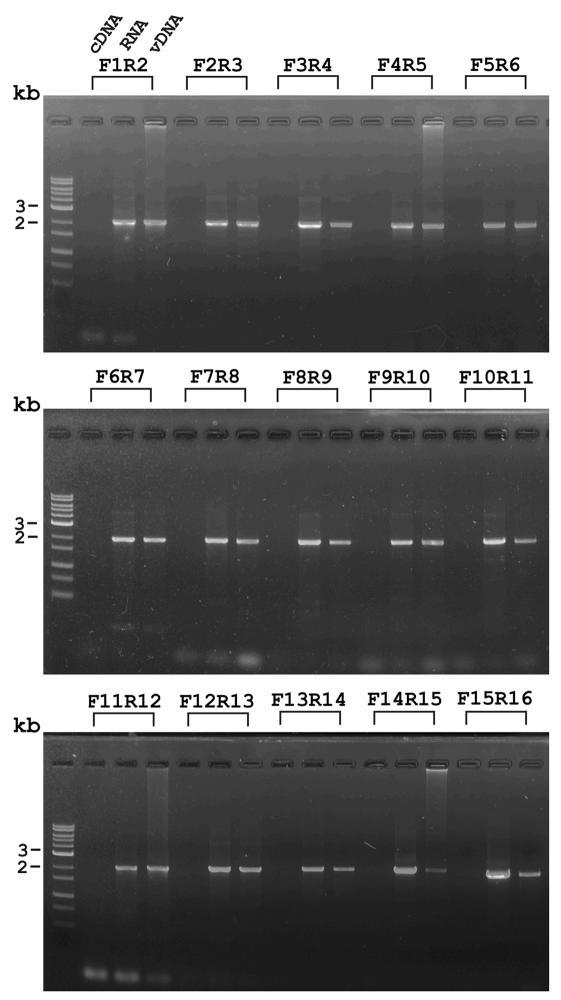

Splicing events in the vp664 transcript.

To demonstrate the existence of the long vp664 transcript as well as to study whether any splicing events had occurred, we conducted a series of RT-PCR analyses to verify its structure. A total of 15 primer pairs were used to generate 15 overlapping RT-PCR products (Fig. 2) that provided complete coverage of the entire coding region. The locations of the primers and the sizes of the predicted amplified products are shown in Table 2, and the results of the analyses are shown in Fig. 8. The fact that no size differences could be discerned between the PCR products amplified from cDNAs and those amplified from the virus genomic DNA suggests that no splicing events occurred. The absence of any amplified PCR products from the RNA-only (negative control) sample means that the PCR products amplified from the cDNAs were not due to contamination by DNA from the viral genome. Sequencing of the overlapping amplicons (data not shown) also completely matched the peptide sequence shown in Fig. 1B, further confirming that there were no deletions and thus that the gene is intron-free.

FIG. 8.

Analysis of the entire 18-kb vp664 transcript by RT-PCRs with 15 sets of primer pairs. Lane headings show the primer pairs, as listed in Table 2. Three reactions were carried out for each primer pair as follows: RNA lanes, total RNA as a negative control; vDNA lanes, viral genomic DNA as a positive control; and cDNA lanes, reverse-transcribed cDNA as a PCR template.

Amino acid sequence analysis.

After BestFit (32) was used to confirm that the amino acid sequence of VP664 has no repeat sequences, the entire sequence was analyzed by several homology searches against various databases to identify the functional motifs and structural features of this giant polypeptide. A search using TMpred against the TMbase database (15) did not find any predicted transmembrane domains; a search using SignalP V1.1 (28) against the SwissProt database (2) was negative for signal peptide prediction; and the results of a search using BLASTP showed that there was no significant homology to any known proteins in the nonredundant NCBI database. However, a search of the PROSITE database by the use of InterProScan identified a cell attachment site signature, the RGD motif, in the N-terminal region, at positions 395 to 397. This motif has been shown to be involved in virus binding to cellular integrins during infection by several viruses, such as rotaviruses (14), papillomaviruses (11), foot-and-mouth disease virus (13), and human herpesvirus 8 (1). Further research will be needed, however, to investigate whether the RGD motif in VP664 mediates the binding of WSSV to shrimp cells or to some extracellular matrix proteins. Three bipartite nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequences were also identified from the PROSITE database, located at positions 2160 to 2176, 2468 to 2484, and 4313 to 4329. Again, the functionality of these domains will need to be determined experimentally, but since an NLS serves to direct nuclear proteins into the nucleus and since the assembly of WSSV virus particles occurs in the nucleus, we would expect this major viral nucleocapsid protein to contain at least one NLS that was functional.

DISCUSSION

For this paper, we used LC-nano-ESI-MS/MS analysis to confirm the existence of the giant polypeptide encoded by vp664 (Fig. 1). A time course analysis of this viral structural protein gene (Fig. 6) showed that vp664 was actively transcribed at the late stage, suggesting that its product is involved primarily in the assembly and morphogenesis of the virion. Immunoelectron microscopy analysis showed that VP664 was localized to the viral nucleocapsid, with numerous gold particles distributed fairly evenly along the periphery of the entire nucleocapsid and not confined to any specific or preferred region (Fig. 5). Transmission electron micrographs published in earlier studies (10, 16, 42) have already shown that the rod-shaped WSSV nucleocapsid is divided into about 15 to 16 vertical segments that are perpendicular to the long axis and about 18 to 20 nm thick. It has been argued that each segment is composed of double rows of 14 globular subunits of 8 nm in diameter (10). In the present study, it was very difficult to confirm unequivocally the existence of these discrete globular subunits. Each segment was characterized, however, by a pattern that repeated itself approximately five times across the width of the virion (Fig. 5C). Curiously, in some of the mature virions, the gold particles had a similar periodicity to this repeating pattern (Fig. 5D), from which we hypothesize that this pattern may in fact arise from the conformation and packaging of the giant VP664 proteins. This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that when WSSV nucleocapsids are purified by CsCl gradient centrifugation and subjected to SDS-PAGE, the only major band (there are several much fainter minor bands) corresponds to VP664 (data not shown), which implies that VP664 is the major component of the nucleocapsid. Thus, the giant polypeptide encoded by vp664 must account for the stacked, patterned rings that characterize the naked WSSV nucleocapsid, if only because there are no other candidate proteins in the nucleocapsid to account for this feature. The distribution of the gold particles further suggests that the N terminus of this protein is left exposed and that each of these gold particles is attached (via the linked VP664 N-terminus-specific antibody) to the exposed N terminus of a single VP664 molecule. We note here, also, that in the immunoelectron microscopy results for the other five antibodies (664-8, 664-9, 664-10, 664-12, and 664-14) (Fig. 3), bound gold particles were not detected (data not shown). We interpret this as further evidence that while the N-terminal region remains exposed, the bulk of this giant molecule is folded in such a way that the binding sites for these other antibodies are inside the protein and thus inaccessible. Another curious observation is that while gold particles were sometimes seen across the top of a mature exposed nucleocapsid (Fig. 5D), gold particles were hardly ever seen across the top of an immature nucleocapsid (e.g., see Fig. 5A, B, and C). From this observation, we infer that the antibody was less tightly bound to the immature nucleocapsid and was thus more easily washed away. The reason for this is unclear, but we speculate that it may be related to changes in the conformation of VP664 as the nucleocapsid matures.

Now that the complete WSSV genome is available, the application of proteomic methodology has led to the identification of many novel viral structural proteins (17, 18, 21; this paper). Most of these viral structural proteins are associated with the viral envelope, and only three, VP26, VP24, and VP15, are considered viral nucleocapsid proteins. For three of these proteins, this determination was made by treating the virions with NP-40 to remove the envelope and then analyzing them by SDS-PAGE or Western blotting (38, 39, 41). However, a more recent study using IEM showed that VP26 is actually localized to the envelope (47). In fact, until now, immunoelectron microscopy has only been successful in locating WSSV envelope proteins, and VP664 is the first WSSV viral nucleocapsid protein to be directly localized by this technique. The present demonstration that the anti-VP664 antibody can be used with IEM to locate the protein in WSSV virions suggests that this antibody will be an invaluable tool for studying the assembly and morphogenesis of WSSV in infected shrimp.

Proteins with molecular masses of >600 kDa have been reported for vertebrates (3, 20, 30, 31, 33, 45, 50), invertebrates (29, 37), and protists (4, 5, 6). The largest known polypeptide identified so far is the titin molecule (38,138 amino acids and 4.2 MDa in humans [3]), which is found in striated muscle. Some invertebrates also have giant molecules (0.5 to 2.0 MDa) that are functionally related to titin although they are not true homologs (29, 37). However, large proteins are much less common in viruses, and so far there are no other known viral proteins whose size comes close to the 6,077 amino acids and (estimated) 664 kDa of VP664. It is tempting to speculate that this uniquely large viral protein is also related to another unique aspect of WSSV, that is, the ability of the WSSV nucleocapsid to change its physical form from a compact naked nucleocapsid (Fig. 4B) to the olive-shaped structure of the mature virion (the volume of which is approximately twice that of the naked nucleocapsid) (Fig. 4A, panel i, and Fig. 5E) to the even larger, loosely packed, exposed mature nucleocapsid (Fig. 4A, panels ii and iii). VP664 is especially implicated in these physical changes because, as argued above, its molecules evidently form the subunits of the stacked rings (Fig. 5C and D). We anticipate that an investigation of the conformational changes in the VP664 protein during viral morphogenesis will help to elucidate these phenomena.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported financially by National Science Council grants (NSC92-2311-B-002-014, NSC92-2317-B-002-001, and NSC-92-2317-B-002-018). Proteomic mass spectrometry analyses were performed by the Core Facilities for Proteomics Research located at the Institute of Biological Chemistry, Academia Sinica, which are supported by a National Science Council grant (91-3112-P-001-009-Y).

We thank Shin-Jen Lin and Chia-Wei Chang for help with the expression and purification of the recombinant VP664 protein. We are indebted to Paul Barlow for his helpful criticism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akula, S. M., N. P. Pramod, F. Z. Wang, and B. Chandran. 2002. Integrin alpha3beta1 (CD 49c/29) is a cellular receptor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV/HHV-8) entry into the target cells. Cell 108:407-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bairoch, A., and B. Boeckmann. 1994. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank—current status. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3578-3580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bang, M. L., T. Centner, F. Fornoff, A. J. Geach, M. Gotthardt, M. McNabb, C. C. Witt, D. Labeit, C. C. Gregorio, H. Granzier, and S. Labeit. 2001. The complete gene sequence of titin, expression of an unusual approximately 700-kDa titin isoform, and its interaction with obscurin identify a novel Z-line to I-band linking system. Circ. Res. 89:1065-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baqui, M. M., N. De Moraes, R. V. Milder, and J. Pudles. 2000. A giant phosphoprotein localized at the spongiome region of Crithidia luciliae thermophila. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 47:532-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baqui, M. M., C. S. Takata, R. V. Milder, and J. Pudles. 1996. A giant protein associated with the anterior pole of a trypanosomatid cell body skeleton. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 70:243-249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barale, J. C., D. Candelle, G. Attal-Bonnefoy, P. Dehoux, S. Bonnefoy, R. Ridley, L. Pereira da Silva, and G. Langsley. 1997. Plasmodium falciparum AARP1, a giant protein containing repeated motifs rich in asparagine and aspartate residues, is associated with the infected erythrocyte membrane. Infect. Immun. 65:3003-3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L. L., J. H. Leu, C. J. Huang, C. M. Chou, S. M. Chen, C. H. Wang, C. F. Lo, and G. H. Kou. 2002. Identification of a nucleocapsid protein (VP35) gene of shrimp white spot syndrome virus and characterization of the motif important for targeting VP35 to the nuclei of transfected insect cells. Virology 293:44-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L. L., H. C. Wang, C. J. Huang, S. E. Peng, Y. G. Chen, S. J. Lin, W. Y. Chen, C. F. Dai, H. T. Yu, C. H. Wang, C. F. Lo, and G. H. Kou. 2002. Transcriptional analysis of the DNA polymerase gene of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. Virology 301:136-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chou, H. Y., C. Y. Huang, C. H. Wang, H. C. Chiang, and C. F. Lo. 1995. Pathogenicity of a baculovirus infection causing white spot syndrome in cultured penaeid shrimp in Taiwan. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 23:165-173. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durand, S., D. V. Lightner, R. M. Redman, and J. R. Bonami. 1997. Ultrastructure and morphogenesis of white spot syndrome baculovirus (WSSV). Dis. Aquat. Organ. 29:205-211. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evander, M., I. H. Frazer, E. Payne, Y. M. Qi, K. Hengst, and N. A. McMillan. 1997. Identification of the alpha6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J. Virol. 71:2449-2456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flegel, T. W. 1997. Major viral diseases of the black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) in Thailand. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 13:433-442. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox, G., N. R. Parry, P. V. Barnett, B. McGinn, D. J. Rowlands, and F. Brown. 1989. The cell attachment site on foot-and-mouth disease virus includes the amino acid sequence RGD (arginine-glycine-aspartic acid). J. Gen. Virol. 70:625-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerrero, C. A., E. Mendez, S. Zarate, P. Isa, S. Lopez, and C. F. Arias. 2000. Integrin αvβ3 mediates rotavirus cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14644-14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann, K., and W. Stoffel. 1993. TMbase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 347:166. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang, C., L. Zhang, J. Zhang, L. Xiao, Q. Wu, D. Chen, and J. K. Li. 2001. Purification and characterization of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) produced in an alternate host: crayfish, Cambarus clarkii. Virus Res. 76:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, C., X. Zhang, Q. Lin, X. Xu, and C. L. Hew. 2002. Characterization of a novel envelope protein (VP281) of shrimp white spot syndrome virus by mass spectrometry. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2385-2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang, C., X. Zhang, Q. Lin, X. Xu, Z. Hu, and C. L. Hew. 2002. Proteomic analysis of shrimp white spot syndrome viral proteins and characterization of a novel envelope protein VP466. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1:223-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inouye, K., S. Miwa, N. Oseko, H. Nakano, T. Kimura, K. Momoyama, and M. Hiraoka. 1994. Mass mortalities of cultured kuruma shrimp Penaeus japonicus in Japan in 1993: electron microscopic evidence of the causative virus. Fish Pathol. 29:149-158. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labeit, S., and B. Kolmerer. 1995. The complete primary structure of human nebulin and its correlation to muscle structure. J. Mol. Biol. 248:308-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li, Q., Y. Chen, and F. Yang. 2004. Identification of a collagen-like protein gene from white spot syndrome virus. Arch. Virol. 149:215-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, W. J., H. T. Yu, S. E. Peng, Y. S. Chang, H. W. Pien, C. J. Lin, C. J. Huang, M. F. Tsai, C. H. Wang, J. Y. Lin, C. F. Lo, and G. H. Kou. 2001. Cloning, characterization, and phylogenetic analysis of a shrimp white spot syndrome virus gene that encodes a protein kinase. Virology 289:362-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo, C. F., J. H. Leu, C. H. Ho, C. H. Chen, S. E. Peng, Y. T. Chen, C. M. Chou, P. Y. Yeh, C. J. Huang, H. Y. Chou, C. H. Wang, and G. H. Kou. 1996. Detection of baculovirus associated with white spot syndrome (WSBV) in penaeid shrimps using polymerase chain reaction. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 25:133-141. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo, C. F., C. H. Ho, S. E. Peng, C. H. Chen, H. C. Hsu, Y. L. Chiu, C. F. Chang, K. F. Liu, M. S. Su, C. H. Wang, and G. H. Kou. 1996. White spot syndrome baculovirus (WSBV) detected in cultured and captured shrimp, crabs and other arthropods. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 27:215-225. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo, C. F., H. C. Hsu, M. F. Tsai, C. H. Ho, S. E. Peng, G. H. Kou, and D. V. Lightner. 1999. Specific genomic DNA fragment analysis of different geographical clinical samples of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 35:175-185. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marks, H., M. Mennens, J. M. Vlak, and M. C. van Hulten. 2003. Transcriptional analysis of the white spot syndrome virus major virion protein genes. J. Gen. Virol. 84:1517-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayo, M. A. 2002. A summary of taxonomic changes recently approved by ICTV. Arch. Virol. 147:1655-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. von Heijne. 1997. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 10:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pudles, J., M. Moudjou, S. Hisanaga, K. Maruyama, and H. Sakai. 1990. Isolation, characterization, and immunochemical properties of a giant protein from sea urchin egg cytomatrix. Exp. Cell Res. 189:253-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosa, J. L., and M. Barbacid. 1997. A giant protein that stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on ARF1 and Rab proteins forms a cytosolic ternary complex with clathrin and Hsp70. Oncogene 15:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosa, J. L., R. P. Casaroli-Marano, A. J. Buckler, S. Vilaro, and M. Barbacid. 1996. p619, a giant protein related to the chromosome condensation regulator RCC1, stimulates guanine nucleotide exchange on ARF1 and Rab proteins. EMBO J. 15:4262-4273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith, T. F., and M. S. Waterman. 1981. Comparison of biosequences. Adv. Appl. Math. 2:482-489. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun, Y., J. Zhang, S. K. Kraeft, D. Auclair, M. S. Chang, Y. Liu, R. Sutherland, R. Salgia, J. D. Griffin, L. H. Ferland, and L. B. Chen. 1999. Molecular cloning and characterization of human trabeculin-alpha, a giant protein defining a new family of actin-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 274:33522-33530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai, J. M., H. C. Wang, J. H. Leu, H. H. Hsiao, A. H. J. Wang, G. H. Kou, and C. F. Lo. 2004. Genomic and proteomic analysis of thirty-nine structural proteins of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J. Virol. 78:11360-11370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai, M. F., C. F. Lo, M. C. van Hulten, H. F. Tzeng, C. M. Chou, C. J. Huang, C. H. Wang, J. Y. Lin, J. M. Vlak, and G. H. Kou. 2000. Transcriptional analysis of the ribonucleotide reductase genes of shrimp white spot syndrome virus. Virology 277:92-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai, M. F., H. T. Yu, H. F. Tzeng, J. H. Leu, C. M. Chou, C. J. Huang, C. H. Wang, J. Y. Lin, G. H. Kou, and C. F. Lo. 2000. Identification and characterization of a shrimp white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) gene that encodes a novel chimeric polypeptide of cellular-type thymidine kinase and thymidylate kinase. Virology 277:100-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tskhovrebova, L., and J. Trinick. 2003. Titin: properties and family relationships. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 4:679-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Hulten, M. C., R. W. Goldbach, and J. M. Vlak. 2000. Three functionally diverged major structural proteins of white spot syndrome virus evolved by gene duplication. J. Gen. Virol. 81:2525-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Hulten, M. C., M. Westenberg, S. D. Goodall, and J. M. Vlak. 2000. Identification of two major virion protein genes of white spot syndrome virus of shrimp. Virology 266:227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Hulten, M. C., J. Witteveldt, S. Peters, N. Kloosterboer, R. Tarchini, M. Fiers, H. Sandbrink, R. K. Lankhorst, and J. M. Vlak. 2001. The white spot syndrome virus DNA genome sequence. Virology 286:7-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Hulten, M. C., M. Reijns, A. M. Vermeesch, F. Zandbergen, and J. M. Vlak. 2002. Identification of VP19 and VP15 of white spot syndrome virus (WSSV) and glycosylation status of the WSSV major structural proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 83:257-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, C. H., C. F. Lo, J. H. Leu, C. M. Chou, P. Y. Yeh, H. Y. Chou, M. C. Tung, C. F. Chang, M. S. Su, and G. H. Kou. 1995. Purification and genomic analysis of baculovirus associated with white spot syndrome (WSBV) of Penaeus monodon. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 23:239-242. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wongteerasupaya, C., J. E. Vickers, S. Sriurairatana, G. L. Nash, A. Akarajamorn, V. Boonsaeng, S. Panyim, A. Tassanakajon, B. Withyachumnarnkul, and T. W. Flegel. 1995. A non-occluded, systemic baculovirus that occurs in cells of ectodermal and mesodermal origin and causes high mortality in the black tiger prawn Penaeus monodon. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 21:69-77. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang, F., J. He, X. Lin, Q. Li, D. Pan, X. Zhang, and X. Xu. 2001. Complete genome sequence of the shrimp white spot bacilliform virus. J. Virol. 75:11811-11820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young, P., E. Ehler, and M. Gautel. 2001. Obscurin, a giant sarcomeric Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor protein involved in sarcomere assembly. J. Cell Biol. 154:123-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhan, W. B., Y. H. Wang, J. L. Fryer, K. K. Yu, H. Fukuda, and Q. X. Meng. 1998. White spot syndrome virus infection of cultured shrimp in China. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 10:405-410. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang, X., C. Huang, X. Xu, and C. L. Hew. 2002. Transcription and identification of an envelope protein gene (p22) from shrimp white spot syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 83:471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang, X., C. Huang, X. Xu, and C. L. Hew. 2002. Identification and localization of a prawn white spot syndrome virus gene that encodes an envelope protein. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1069-1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang, X., X. Xu, and C. L. Hew. 2001. The structure and function of a gene encoding a basic peptide from prawn white spot syndrome virus. Virus Res. 79:137-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhen, Y. Y., T. Libotte, M. Munck, A. A. Noegel, and E. Korenbaum. 2002. NUANCE, a giant protein connecting the nucleus and actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 115:3207-3222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]