Abstract

ING1 was identified as an inhibitor of growth and has been described as a tumor suppressor. Furthermore, the expression of ING1 is induced in senescent cells and antisense ING1 extends the proliferative life span of primary human fibroblasts. Cooperation of p33ING1 with p53 has been suggested to be an important function of ING1 in cell cycle control. Intriguingly, it has been shown that p33ING1 is associated with histone acetylation as well as with histone deacetylation function. Here we show that p33ING1 is a potent transcriptional silencer in various cell types. However, the silencing function is independent of the presence of p53. By use of deletion mutants two potent autonomous and transferable silencing domains were identified, but no evidence of an activation domain was found. The amino (N)-terminal silencing domain is sensitive to the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) whereas the carboxy-terminal silencing function is resistant to TSA, suggesting that p33ING1 confers gene silencing through both HDAC-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Interestingly, the presence of oncogenic Ras, which is able to induce premature senescence, increases the p33ING1-mediated silencing function. Moreover, ING1-mediated silencing was reduced by coexpressing dominant-negative Ras or by treatment with the mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitor PD98059 but not by treatment with SB203580, an inhibitor of the p38 pathway. In addition, we show that both silencing domains of ING1 are involved in cell cycle control, as measured by inhibition of colony formation of immortalized cells and by thymidine incorporation of primary human diploid fibroblasts (HDF). Interestingly, p33ING1 expression induces features of cellular senescence in HDFs.

p33ING1 (for “inhibitor of growth 1”) was identified in a selection system for genes whose inactivation promotes neoplastic transformation (9, 15, 18). p33ING1 is a nuclear protein that has been shown to interact with the tumor suppressor p53, and overexpression of p33ING1 inhibits cell cycle progression in the G1 phase in a p53-dependent manner (17, 35). The human p33ING1 locus encodes three different splice variants, leading to the production of proteins that share a common carboxy-terminal region but have various N termini with sizes of 47 kDa (p47ING1), 33 kDa (p33ING1), and 24 kDa (p24ING1) (21, 48). The C termini of these ING isoforms share homologies to the plant homeodomain zinc finger motif that is commonly found in chromatin-associated proteins (9). Recently other ING1-related genes termed p33ING2, p47ING3, p29ING4, and p28ING5 that are encoded by different genes were identified (15, 22). The ING protein family shows high conservation in the C termini, suggesting an important functional role of the C terminus of the ING gene family.

Aberrant expression of p33ING1 or mutations of p33ING1 have been found in primary tumors and tumor cell lines of different origins, including neuroblastoma, lymphoid cell lines, breast cancer and cell lines, gastric cancer, and head and squamous cell carcinomas (6, 8, 21, 24, 28, 37-39, 41-43, 49, 55, 57). The human ING1 locus maps to chromosome 13q33-34, a site that is frequently associated with loss of heterozygosity in various types of cancers (16, 30, 47, 64).

Besides the interplay of p33ING1 and p53 in cell cycle control, both cooperate for other cellular functions. p33ING1 can sensitize cells to genotoxic stress in a p53-dependent manner (17). Furthermore, the repair mechanism induced by UV damage is enhanced by overexpression of p33ING1 and requires the participation of p53 (9).

Moreover, p33ING1 was shown to be involved in cellular life-span regulation. p33ING1 levels are increased in human senescent fibroblasts and epithelial cells, while inhibition of ING1 gene expression leads to replicative life-span extension of primary human fibroblasts (19, 50). Premature senescence was originally found to be induced by expression of the oncogenic Ras (Ras-Val12, RasV12) in primary human diploid fibroblasts (51).

Interestingly, it was reported that p33ING1 is associated with chromatin-modifying activity. p33ING1 is associated with the Sin3A corepressor complex and was shown to harbor a transcriptional repression function (29, 54, 62). Thereby, human p33ING1 associates in vivo with Sin3A, SAP30, HDAC1, RbAp48, and other proteins to form large protein complexes, whereas the splice variant p24ING1 does not. The association with the Sin3A complex and histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity is mediated by the p33ING1 N terminus, which is lacking in the splice variant p24ING1. In contrast, p33ING1 has also been shown to be associated with histone acetyltransferase activity (61) and to coactivate the estrogen receptor (56, 58).

We investigated the transcriptional properties of p33ING1 to define the protein domains involved in transcriptional regulation. We show that human p33ING1 harbors a strong transferable silencing function. The repression function is independent of the presence of functional p53. Deletion mapping revealed two transferable repression domains. One is localized in the N terminus and is TSA sensitive, while the other is located in the conserved C terminus and is TSA insensitive, indicating an HDAC-independent repression mechanism. In addition, the repression function of p33ING1 is enhanced by the Ras/Raf pathway. Furthermore, we show that both silencing domains are involved in cell cycle regulation by p33ING1 in immortalized and primary cells.

(Part of this work is included in the Ph.D. thesis of F. Goeman, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

cDNAs of human p33ING1 and p33ING1 deletions were cloned in frame into the pAB-gal1-94 linker (1) or the pLPC vector (51) by use of standard cloning techniques. The reporter 17mer6x-tkCAT was described earlier (2). Expression vectors for Ras and Raf and the reporter UAS4x-tk-Luc were kindly provided by S. Tenbaum and P. Crespo. The telomerase promoter reporter construct (10) was obtained from S. Bacchetti and A. Farsetti, and the expression vector for human p53 was obtained from M. Dobbelstein.

Cell culture.

The human lung carcinoma cell line H1299, monkey kidney cell line CV1, NIH 3T3 immortalized mouse fibroblasts, Ltk- transformed mouse fibroblasts, human kidney HEK 293T cells, and IMR90 primary human diploid fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Chicken erythrocyte HD3 cells were grown in 8% fetal calf serum and 2% chicken serum supplemented with penicillin-streptomycin at 41°C with 5% CO2. DEAE-dextran transfection was carried out as described elsewhere (3). Calcium phosphate transfection was performed with minor changes according to the method of Baniahmad et al. (4). Briefly, 6-well dishes were plated 4 to 12 h prior to addition of the DNA transfection cocrystals, which were generated by mixing DNA and HeBS (final concentrations, 0.137 M NaCl, 6 mM glucose, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) with CaCl2 (final concentration, 100 mM) through a 5-s vortexing and 20-min incubation step at room temperature. The following amounts of DNA were used: 0.9 μg of reporter, 0.9 μg of expression vector for Gal4 DNA-binding domain fusions, and 3.5 μg for Ras/Raf expression plasmids. The reporter pCMV-lacZ (0.2 μg) was used to standardize for transfection efficiency.

For trichostatin A (TSA) (Biomol) treatment, 0.9 μg of reporter and 2 μg of Gal expression vector were used. After overnight incubation with the DNA-CaPO4 crystals, cells were washed and incubated for an additional 24 h (chloramphenicol acetyltransferase [CAT] reporter), 48 h (Luc reporter), or 72 h for Ras or Raf expression prior to harvest. Kinase inhibitors PD98059 and SB203580 (Calbiochem) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and used at final concentrations of 10 and 25 μM, respectively. PD98059 and SB203580 were incubated for 25 h prior to cell harvest. DMSO-treated cells were used as controls. TSA dissolved in ethanol was added to the cells at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml 16 h after transfection. Cells were harvested 10.5 h after TSA or ethanol treatment.

Each set of experiments was performed at least three times. At least two different double-CsCl-gradient-purified plasmid preparations were used.

Retroviral transduction.

Retroviral infection of human primary fibroblasts was done essentially as described elsewhere (44, 51), with minor modifications. In brief, IMR90 early-passage (<40 population doubling levels) human lung diploid fibroblasts, which had previously been infected with a retroviral vector driving expression of the ecotropic receptor, were used for retroviral transduction. For the production of virus, 293T cells were transiently transfected with the appropriate retroviral vector together with the pCLEco vector that encodes the ecotropic envelope protein (36). After 48 h, the supernatant containing viral particles was filtered, diluted 1 in 4 with fresh medium in the presence of 4 μg of Polybrene/ml, and added to IMR90 cells seeded the previous day at a density of 8 × 105 cells per 10-cm-diameter dish. This procedure was repeated 24 h later. Successfully infected cells were selected with puromycin (2 μg/ml) for 3 to 5 days and used for the indicated assays. Senescence-associated β-Gal (SA-β-Gal) staining was carried out as described previously (11) by use of 40,000 cells per well in a 6-well plate.

Thymidine incorporation.

For [3H]thymidine incorporation assays, 2 × 103 cells per well were seeded in triplicate in 96-well plates and the rate of [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured at several time points thereafter. For each point, 1 μCi of methyl-[3H]thymidine (Amersham) (46 Ci/mmol) was added to each well, and the amount of [3H]thymidine incorporated into DNA was measured 24 h later by use of an Inotech cell harvester apparatus and a Wallac Trilux 1450 Microbeta scintillation counter.

Colony formation assays.

NIH 3T3 cells were plated into 6-well dishes (9 × 104cells/well) and 24 h later were transfected with 3 μg of pLPC (empty vector control), pLPC-p33ING1 (full length), pLPC-p33ING1 (amino acids [aa] 1 to 171), and pLPC-p33ING1 (aa 171 to 279) by employing the CaPO4 method. The transfection efficiency was controlled using cotransfected pCMV-lacZ and assayed for β-Gal activity prior to selection. At 48 h posttransfection the cells were transferred to 10-cm-diameter dishes and selected on 2 μg of puromycin/ml. After 2 weeks of selection the resistant colonies were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, stained with crystal violet (0.1% in phosphate-buffered saline), and counted. The experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated three times.

RESULTS

The p33ING1 tumor suppressor protein is a potent transcriptional silencer in various cells.

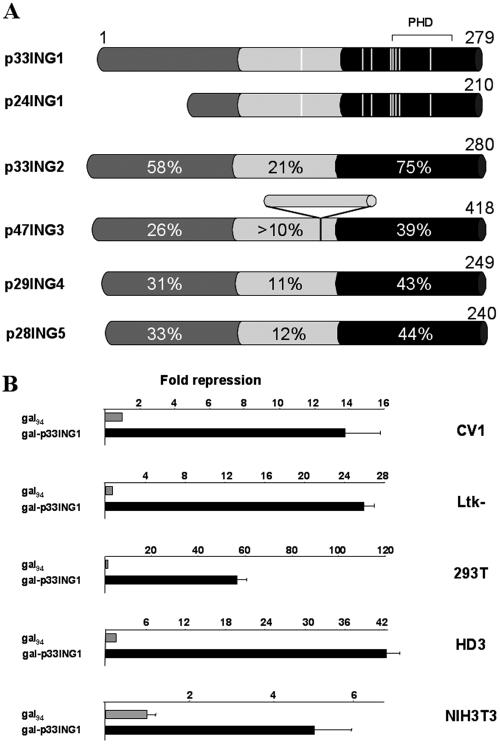

Members of the p33ING1 protein family are encoded by different genes with high sequence conservation in the carboxy-terminal region (Fig. 1A). The C termini exhibit homologies to the plant homeodomain. Also, the N termini of the p33ING1 family share significant sequence conservation, especially between p33ING1 and p33ING2, while the central parts share no or only limited homologies. Notably, the identified p33ING1 mutations isolated from tumors are mostly located in the highly conserved C-terminal part (Fig. 1A), indicating an important role for the p33ING1 C terminus (7, 8, 15, 21, 23). Since p24ING1 is a splice variant of p33ING1, the mutations are also present in that splice variant.

FIG. 1.

The p33ING1 tumor suppressor protein harbors a potent transferable silencing domain functional in various cell types. (A) Schematic view of p33ING1 and its splice variant p24ING1 and homologies to other members of the ING1 protein family, which are encoded by different genes. The ING1 protein family shares a tripartite structure: a conserved N terminus, a nonconserved central part, and a highly conserved carboxy terminus. The percentages of identical amino acids in relation to p33ING1 are indicated. The positions of the previously identified mutations of p33ING1 are highlighted (white lines). PHD, plant homeodomain. (B) Various cell lines were cotransfected with expression vectors coding for the Gal4 DNA binding domain Gal94 (amino acids 1 to 94) or the Gal-p33ING1 fusion together with the reporter 17mer6x-tkCAT. The mean of the values obtained with Gal94 was set arbitrarily at 1, and the repression by the p33ING1 fusion is indicated. The data were normalized to the values obtained with the cotransfected β-Gal expression vector (pCMV-lacZ). The error bars represent deviations of the means from two independent transfections. Please note the different scaling parameters for individual graphs.

To test the transcriptional properties of p33ING1 in various cells we used the established Gal4 fusion system and generated a fusion of full-length p33ING1 with the DNA binding domain of Gal4 encompassing amino acids 1 to 94 that lacks the weak transactivation function between amino acid 94 and 147 (1). We have tested these fusions in various cell types, including CV1, Ltk-, HEK 293T, HD3, and NIH 3T3 cells, by use of the 17mer6x-tkCAT reporter (2). Compared to the Gal vector control, p33ING1 exhibited transcriptional silencing function in all cell types tested (Fig. 1B). The silencing function mediated by p33ING1 is dependent on the Gal fusion (data not shown). This effect was very high in 293T and HD3 cells (40- to 60-fold), whereas it was only moderate (5-fold) in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts, with CV1 and Ltk- cells giving intermediate values.

Thus, p33ING1 harbors transcriptional silencing function in various cell types.

The silencing function of p33ING1 is independent of the presence of p53.

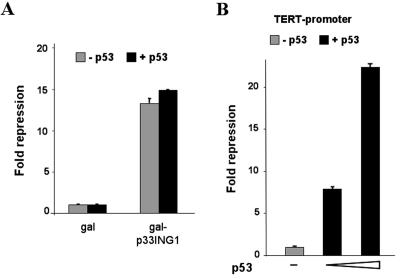

Because various p33ING1 functions have been shown to be dependent on the presence of the tumor suppressor p53, we analyzed whether the silencing function is dependent on p53 and/or whether the silencing can be modulated by p53. For this purpose we used the p53-negative human lung carcinoma cell line H1299 (34). Cotransfection experiments revealed that p33ING1 exhibits a strong silencing function in H1299 cells, suggesting that the ING-mediated repression is not dependent on the presence of p53 (Fig. 2A). Also, cotransfection of p53 did not significantly change the silencing function of p33ING1 (Fig. 2A). We have used a range from 50 to 500 ng of p53 expression plasmid without a significant effect on ING-mediated silencing (data not shown). As a positive control for p53 action in these cells we used the human TERT promoter, which is known to be repressed by p53 (26). As expected, coexpression of 50 or 500 ng of p53 expression plasmid led to a strong repression of the human TERT promoter (Fig. 2B), indicating that p53 is functional in these cells. Thus, it suggests that p53 is not involved in p33ING1-mediated silencing and is not a corepressor for p33ING1.

FIG. 2.

Silencing function of p33ING1 is independent of the tumor suppressor p53. (A) The human lung carcinoma cell line H1299, lacking functional p53, was cotransfected with either Gal-1-94 or Gal-p33ING1 together with the reporter 17mer6x-tkCAT. The mean of the values obtained with Gal94 was set arbitrarily at 1, and the severalfold repression obtained by the p33ING1 fusion is indicated. Black bars indicate values obtained with cotransfected p53 expression vector (100 ng), and gray-shaded bars indicate the values obtained with the empty control vector. The transfection efficiency was normalized with lacZ values. (B) As a control for p53 function in H1299 cells, the human telomerase promoter (Δ1009 TERT-Luc) was used. The mean value obtained in the absence of p53 (empty vector) was set arbitrarily at 1 (gray bar). Cotransfection of 50 and 500 ng of the p53 expression vector led to repression of the TERT promoter (black bars). The error bars represent deviations of the means from two independent transfections.

To analyze the possibility of a vice versa situation—i.e., to determine whether p33ING1 acts as a corepressor for p53-mediated repression—specific promoters which are repressed by p53 were investigated. We chose three promoters, human TERT (Δ1009), multidrug resistance promoter (−1202), and the cyclin B1 (−287) promoter, previously established to contain p53 response elements and to be repressed by p53 (25, 33, 63). All three promoters were repressed by the presence of wild-type human p53 in H1299 cells. Since coexpression of full-length p33ING1 expression did not significantly change the repression mediated by p53 (unpublished data), this result indicates that p33ING1 does not act as a corepressor for p53.

Taken together, the data suggest that the transcriptional silencing mediated by p33ING1 is independent of the tumor suppressor p53 and vice versa; i.e., the p53-mediated gene repression is independent of p33ING1.

p33ING1 harbors two transferable silencing domains.

To identify functional domains of p33ING1 with regard to activation and/or repression, a battery of overlapping and nonoverlapping Gal-p33ING1 fusions was generated and tested with different cell types (Fig. 3). In CV1 cells, both the N-terminal mutant (aa 1 to 76) and the C-terminal mutant (aa 171 to 279) harbor a transcriptional silencing function, while the central p33ING1 part (aa 76 to 171) exhibits only a weak repression function. This indicates that p33ING1 harbors at least two separable transcriptional silencing functions. To analyze the C-terminal conserved domain in more detail, overlapping deletions (aa 76 to 279 and 110 to 264) were created. These mutants exhibit similar abilities to silence transcription, as seen with the C-terminal conserved domain. However, the smaller p33ING1 mutant (aa 189 to 264) showed no significant repression function (Fig. 3). For 293T cells, both the N and C termini harbor strong silencing function, albeit at a reduced level compared to that seen with full-length p33ING1. The central part of ING1 (aa 76 to 171) and the mutant aa 189 to 264 only weakly repress promoter activity. Use of the combined central and C-terminal parts (aa 76 to 279) leads to a strong repression function to an extent similar to that seen with full-length p33ING1. As a control, the expression of those Gal-p33ING1 deletion mutants that exhibited weak or no silencing function was verified by Western blotting with cell extracts by use of an anti-Gal4 antibody (data not shown), indicating that the lack of transcriptional repression by the ING1 mutants is not due to lack of expression.

FIG. 3.

Delineation of the silencing domains of p33ING1. The transcriptional effect of the indicated gal-p33ING1 deletion mutants on the activity of the reporter, 17mer6x-tkCAT, was analyzed in CV1, HEK 293T, and H1299 cells. The values obtained with Gal alone were set arbitrarily at 1. Values were normalized for transfection efficiency with lacZ values. The error bars represent the variations from the means of three independent transfections. The numbers indicate the positions of amino acids of the p33ING1 deletions. The gray underlying shadowed boxes indicate the two strong silencing domains in the N and C terminus of p33ING1. The error bars represent deviations of the means from two independent transfections.

In H1299 cells, the N-terminal p33ING1 domain (aa 1 to 76) harbored a repression function, which is similar to the results seen with full-length p33ING1. The central part (aa 76 to 171) and the C terminus (aa 171 to 279) tested individually revealed weak repression function. In line with that result, the combination of the central part with the C terminus (aa 76 to 279), which corresponds to the p24ING1 splice variant, or the mutant aa 110 to 264 exhibited a silencing function, while the mutant aa 189 to 264 lacks a repression function (Fig. 3). This suggests that p33ING1 harbors two separable and strong transrepression domains located in the N and C terminus. The central part has only a weak repression function but synergistically increases that of the conserved C terminus.

Taken together, these results indicate that p33ING1 harbors at least two strong repression domains and that one is localized in the N terminus and the other is localized in the conserved C terminus.

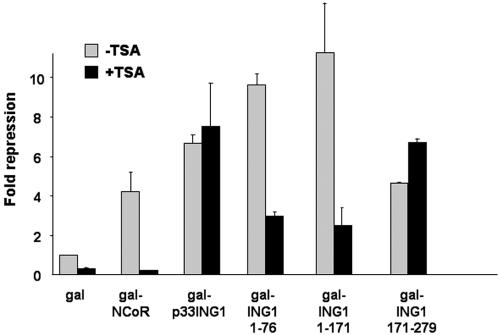

TSA-sensitive and -resistant silencing mediated by the p33ING1 tumor suppressor.

It was previously shown that the Sin3A complex binds to the N terminus of p33ING1 but not to p24ING1, suggesting that the first 70 aa of p33ING1 are essential for recruiting Sin3A and HDAC activity (29, 54). To delineate the mode of transcriptional repression of each of the p33ING1 silencing domains, the specific HDAC inhibitor TSA was used. As a positive control for HDAC-mediated repression and inhibition by TSA, the nuclear corepressor NCoR fused to the Gal4 DNA binding domain was included (Fig. 4). Addition of TSA led to a reduction of transcriptional repression by NCoR. Surprisingly, the full-length p33ING1 showed resistance to TSA treatment. Interestingly, the N- and C-terminal silencing domains exhibited differences in their responses to TSA. The activity of the p33ING1 N terminus (aa 1 to 76) was significantly reduced by the presence of TSA, which is in agreement with previous findings (29, 54). Similar results were obtained using p33ING1 aa 1 to 171. In contrast to NCoR results, we did not observe a complete relief of N-terminal-mediated silencing by TSA. Notably, the C-terminal silencing function exhibits resistance to TSA treatment, indicating the presence of a silencing mechanism independent of HDAC activity. Although the promoter activity was in general enhanced by TSA treatment, an observation we made with several other promoters (13), the overall transcriptional silencing by p33ING1 remained potent.

FIG. 4.

Differential effects of TSA on the C- and N-terminal p33ING1 silencing domains. The HDAC inhibitor TSA (100 ng/ml) was used to test for HDAC-sensitive or -resistant silencing by treatment of CV1 cells transfected with full-length p33ING1 or deletions lacking the N-terminal or C-terminal silencing domain of p33ING1. Values obtained with Gal94 in the absence of TSA were set arbitrarily at 1. As a positive control for TSA-sensitive silencing, Gal-NCoR was used. The error bars represent deviations of the means from two independent transfections.

Taken together, these results indicate that the N terminus of p33ING1 showed TSA sensitivity while the conserved C terminus exhibited TSA resistance. This indicates that p33ING1 uses HDAC-dependent and -independent mechanisms for transcriptional repression.

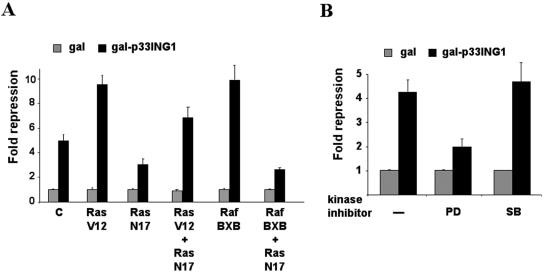

Ras increases p33ING1-mediated silencing.

Prolonged expression of the oncogenic form of Ras in primary cells triggers a cell cycle arrest reminiscent of cellular senescence (51), which is mediated by the Raf-mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (31). As mentioned above, p33ING1 has been linked to cellular senescence. Furthermore, the particulars of regulation of p33ING1 function and its possible connection to mitogenic or antimitogenic pathways are largely unknown. On the basis of these findings, we decided to explore whether p33ING1 function might be influenced by Ras signaling. For this purpose, RasV12, the dominant active Ras, and, as a control, RasN17, the dominant-negative Ras, were each coexpressed together with Gal-p33ING1. Interestingly, coexpression of the dominant active RasV12 enhances the repression function of p33ING1 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the dominant-negative RasN17 in part inhibits p33ING1-mediated silencing, most likely by interfering with endogenous Ras signaling. Since Ras mediates the signal transduction pathway through the Raf-MAPK pathway, we also tested Raf-BXB, the constitutively active Raf (12, 59) (Fig. 5A). The enhancement of p33ING1-mediated silencing by Raf-BXB was similar to the effect observed with RasV12. Coexpression of RasV12 or Raf-BXB together with RasN17 also led to a reduced silencing of p33ING1. This might be explained either through effects on the endogenous Ras signaling or through possible indirect effects of RasN17 on Raf action via other effector pathways (14). These results indicate that the Ras signal transduction pathway can modulate the silencing function of p33ING1.

FIG. 5.

The Ras signal transduction pathway enhances p33ING1-mediated gene silencing. (A) The effect of dominant active Ras (RasV12), dominant-negative Ras (RasN17), or constitutive active Raf (Raf BXB) on the Gal-p33ING1 full-length fusion in CV1 cells was analyzed. Expression vectors were cotransfected with the reporter UAS4x-tkLuc, and each experimental setup contained four independent transfections. The values obtained with Gal alone were set arbitrarily at 1. Values were normalized for transfection efficiency with lacZ. C, empty expression vector. (B) The inhibitor of MAPK (MEK) signaling PD98059 (PD) (10 μM), the p38 kinase inhibitor SB203580 (SB) (25 μM), and DMSO (vehicle) as a control were tested for their influence on p33ING1-mediated silencing in a setup similar to that described for panel A. The values obtained with Gal alone were set arbitrarily at 1. Values were normalized for transfection efficiency with lacZ. Only PD98059 inhibits p33ING1-mediated silencing.

As an additional verification, we used inhibitors of the endogenous MAPK-activated pathway in the presence of 10% serum (Fig. 5B). Treatment of cells with PD98059, a specific inhibitor of the ERK signaling pathway, led to reduced silencing function of p33ING1 to an extent similar to that seen with the coexpression of RasN17, suggesting that the p33ING1-mediated silencing is modulated by the Ras-ERK signaling. Notably, treatment with SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK, had no effect on p33ING1-mediated transcriptional silencing. These data indicate that activation of the Ras-Raf signal transduction pathway enhances p33ING1-mediated silencing through the ERK pathway.

The silencing domains of p33ING1 are involved in cell growth regulation.

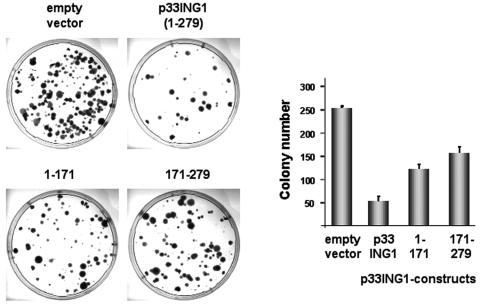

To analyze whether the silencing domains of p33ING1 are involved in cell cycle regulation, both immortalized NIH 3T3 and primary human diploid fibroblasts were used. Immortalized NIH 3T3 cells were stably transfected with either empty vector or expression vectors for full-length p33ING1, p33ING1 lacking the conserved C terminus, or the conserved C terminus alone. Cells were selected for stable integration for 2 weeks. The obtained colonies were stained and counted (Fig. 6). Compared to the results seen with the empty vector, expression of p33ING1 strongly reduced colony numbers. This is in agreement with previous observations (29). Interestingly, the expression of the ING1 deletion lacking the C-terminal silencing domain (aa 1 to 171) resulted in reduced colony numbers, indicating that the C terminus plays an important role in inhibiting cell proliferation. In line with that result, expressing the highly conserved C terminus of ING1 (aa 171 to 279) alone led to reduced colony formation numbers. This indicates that the p33ING1 C terminus is involved in colony formation and cooperates with the N terminus in the full-length protein. No colonies were detected using untransfected or mock NIH 3T3 cells.

FIG. 6.

The highly conserved ING1 C terminus is involved in cell growth regulation. A colony formation assay was performed using immortalized NIH 3T3 cells transfected with selectable expression vectors for full-length p33ING1 and the indicated ING1 deletions. The cell colonies were stained with crystal violet after selection with antibiotics for 2 weeks (left panel); the colony numbers were then counted and plotted in a graph (right panel). Each experiment set contained triplicates for the procedures performed for each of the constructs, which were repeated three times.

Taken together, these results indicate that p33ING1 and each of its silencing domains individually inhibit cell growth of immortalized cells.

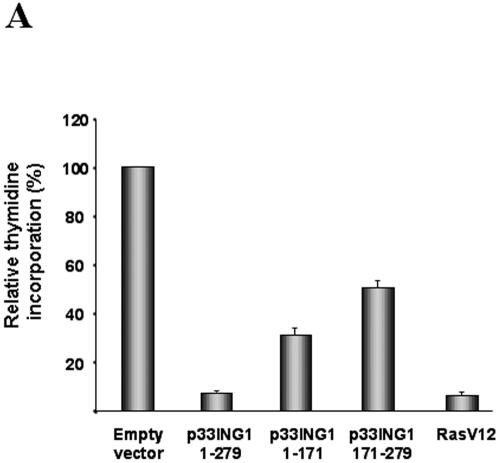

To obtain more information about the importance of the silencing domains of p33ING1 in its antiproliferative action, we ectopically expressed p33ING1 and the deletion mutants in IMR90 human primary fibroblasts by retroviral transduction. As a control, we used a vector expressing oncogenic Ras, which causes a well-characterized cell cycle arrest reminiscent of senescence in this cell type (51). After a short selection, we analyzed the DNA synthesis rate and the morphology of infected cells. To estimate the division rate, we measured thymidine incorporation into newly synthesized DNA. This analysis revealed that full-length p33ING1 is a potent inhibitor of DNA synthesis in IMR90 cells comparable to oncogenic Ras (Fig. 7A). The thymidine uptake was inhibited approximately 10-fold relative to the results seen with empty-vector-infected cells. Next, we determined the consequences of the deletion of the C-terminal (aa 1 to 171) or the N-terminal (aa 171 to 279) silencing domain. In similarity to the results seen with NIH 3T3 cells, independent deletion of either silencing domain resulted in a partial reduction in the ability of p33ING1 to cause cell cycle arrest in IMR90 fibroblasts. The expression of p33ING1 and p33ING1 deletions was confirmed by both Western analysis (data not shown) and immunofluorescence (unpublished data), revealing that expression of the C-terminal silencing domain is weaker than that seen with full-length protein. This may be indicative of an even more potent role of the C-terminal silencing domain in this aspect. These observations underline the important function of both transcriptional silencing domains in p33ING1 biological function.

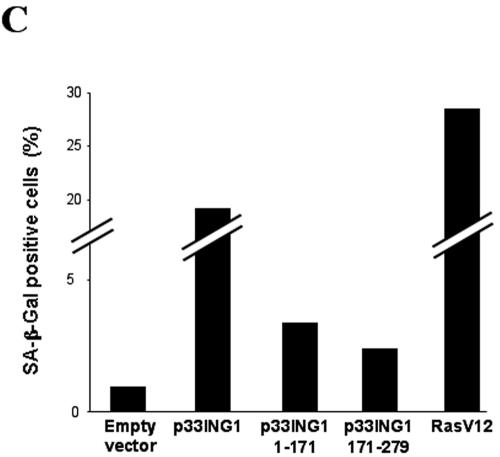

FIG. 7.

ING1 induces morphological changes and growth arrest of primary human diploid fibroblasts. The human primary diploid fibroblasts expressing an ecotropic receptor were retrovirally transformed with selectable expression plasmids for the oncogenic Ras, RasV12, full-length p33ING1, and the indicated ING1 deletions. (A) Thymidine incorporation as an indicator of DNA synthesis. Triplicate experiments were performed, and the values obtained with the empty vector control were set arbitrarily at 100%. (B) Phase-contrast pictures of transduced human diploid fibroblasts with the indicated expression vectors. (C) Expression of SA-β-Gal. A total of 200 human primary diploid fibroblasts were counted each time; the percentages of cells expressing SA-β-Gal are shown.

Senescent human fibroblasts acquire a distinct cell morphology. In contrast to the thin, elongated shape of normal, actively growing early-passage IMR90 cells, senescent counterparts display a flat, enlarged phenotype. As mentioned above, there are indications of a possible role of p33ING1 in senescence (19, 50). Therefore, we wished to determine whether the arrest induced by p33ING1 displays features of cellular senescence. Retroviral transduction with p33ING1 resulted in a change to senescence-like cell morphology, as documented by phase-contrast microscopy (Fig. 7B). Notably, the N terminus of p33ING1 induced morphological changes similar to those seen with the full-length protein, in agreement with its ability to cause cell cycle arrest, albeit at a reduced level. The changes in cell morphology caused by p33ING1 were similar to but not identical to those provoked by oncogenic Ras. In both cases, cells lost their normal thin and long shape; p33ING1-infected cells showed a morphology more similar to that seen with IMR90 cells that have reached senescence because of accumulation of population doublings, whereas Ras-infected cells were even larger and with a more irregular shape, in agreement with previous reports (31, 51).

A further characteristic of cellular senescence is the expression of specific senescence-associated SA-β-Gal (11). We tested for expression of SA-β-Gal activity in p33ING1-infected primary human fibroblasts by use of RasV12 as a control (Fig. 7C). In accordance with the previous observations, p33ING1 induces SA-β-Gal activity to a extent similar to that seen with oncogenic Ras, suggesting that p33ING1 has potency similar to that of RasV12. In addition, we analyzed the consequences of the deletion of either the C terminus (aa 1 to 171) or the N terminus (aa 171 to 279) in this assay. Both domains retain some ability to induce SA-β-Gal activity but to a much lesser extent than that seen with full-length p33ING1, which indicates that each of the silencing domains is involved in induction of SA-β-Gal activity.

Taken together, these results indicate that ectopic expression of p33ING1 in human diploid fibroblasts causes a cell cycle arrest with some features of cellular senescence and that the N and C termini cooperate in inducing cell cycle arrest.

DISCUSSION

We have characterized the transcriptional potential and effects on cell cycle regulation of the tumor suppressor p33ING1. Using a battery of ING1 deletion mutants, we have identified two potent silencing domains that were transferable to a heterologous protein and which are therefore defined as true functional silencing domains. Interestingly, these silencing domains are likely to exhibit their silencing function through different mechanisms. The N terminus of p33ING1 is associated with HDAC activity that is lost when the first 70 amino acids are deleted. The C terminus of ING1 harbors a potent silencing domain that is not TSA sensitive, suggesting that the highly conserved ING1 C terminus exerts an HDAC-independent mechanism for gene silencing which has not yet been elucidated. Since the full-length p33ING1-mediated silencing is TSA resistant, this result suggests that the C-terminal, TSA-resistant, silencing domain dominates over the N-terminal, TSA-sensitive, silencing domain in the full-length protein. Interestingly, comparing the ING proteins reveals that the C termini are highly conserved, indicating an important role for the C terminus. In line with that finding, naturally occurring and tumor-associated mutations of p33ING1 were predominantly identified in its C terminus. This strongly points towards an important function localized in the C terminus of the ING family. We have observed a potent silencing function in the C terminus, implying that gene silencing is one of the important ING functions.

The association of p33ING1 with both HDACs and histone acetyltransferases has been described previously (29, 40, 54, 61). This suggests that p33ING1 may harbor intrinsically both transrepression and transactivation functions (27). However, under the conditions used we were unable to detect a transactivation function. This indicates either that p33ING1 does not harbor a transferable transactivation function or that p33ING1 associates with histone acetyltransferase activity under different conditions. Recently, it was reported that some ING proteins harbor a ligand-binding domain for phosphoinositides in the C terminus (20). However, the relevance of this interaction on ING1 protein function remains to be established.

Although a large number of p33ING1 functions are dependent on the presence of p53 (9, 17, 35, 52, 53, 60), the silencing function of p33ING1 is shown here to be independent of p53. This strongly suggests that silencing mediated by p33ING1 is one of the few known functions that are independent of p53 and is in agreement with recent reports of p53-independent transcriptional control by p33ING1 (27).

We have investigated the role of the Ras signal machinery in p33ING1 silencing and observed that activation of the Ras-Raf pathway enhances the silencing function of p33ING1. Using the dominant-negative Ras or the MEK-specific inhibitor PD98059 revealed that p33ING1-mediated silencing is reduced whereas significant silencing function is still being retained despite inhibiting the Ras signaling. This indicates that p33ING1 exerts its silencing function through both Ras-dependent and Ras-independent mechanisms. At present, we do not know the mechanism linking Ras to p33ING1 function, but it is not likely to involve a direct phosphorylation of p33ING1, since we have not been able to detect phosphorylation of p33ING1 by immunoprecipitates of p38, ERK, or JNK (data not shown). This suggests that the connection between the Ras transduction machinery and p33ING1 might instead involve the regulation of other genes and/or modification of other cellular factors.

In this report, we have also explored the correlation between the transcriptional repression of p33ING1 and its antiproliferative action. Supporting an important role for the two silencing domains we have described, we find that independent deletion of each of the domains severely impairs the effect of ING1 on cell cycle progression, both in mouse immortal cells and human primary fibroblasts. Having used the two separated silencing domains in combination, we have evidence that in the full-length protein each domain is more effective in mediating silencing as well as growth inhibition (unpublished data), indicating that some degree of cooperation exists in the full-length p33ING1. Our results have led us to a working model in which each silencing domain interacts with a distinct protein complex, allowing each silencing domain to act independently, whereas these protein complexes are able to interact with each other to enhance the silencing capability and growth regulation by p33ING1 only in the full-length situation.

The use of human primary fibroblasts has also allowed us to investigate the possible involvement of p33ING1 in the implementation of cellular senescence. A participation of p33ING1 has previously been suggested on the basis of the increased levels of the protein with accumulation of population doublings in several cell types. Here, we have shown that ectopic expression of p33ING1 is sufficient to induce cell cycle arrest in human primary fibroblasts with some features of cellular senescence, suggesting an important role of p33ING1 in the implementation of the senescence arrest.

Chronic activation of the Ras promitogenic signaling pathway causes a senescence-like cell cycle arrest in primary fibroblasts (31, 51, 65). This response is associated with the induction of cell cycle inhibitors such as p16INK4a, p15INK4b, and p21CIP (5, 32, 45, 51) or the PML protein (46), among other changes. Here, we have shown on the one hand that ectopic expression of p33ING1 can similarly induce a cell cycle arrest with some features of cellular senescence and on the other hand that the p33ING1-mediated silencing is modulated by the Ras pathway. Taken together, these observations raise the possibility of an interplay between Ras and p33ING1 in the induction of senescence which we intend to explore in depth.

Acknowledgments

We greatly thank J. M. Freije and C. Lopez-Otin for providing the p33ING1 cDNA, M. Dobbelstein for the p53 expression vector and H1299 cells, S. Bacchetti and A. Farsetti for providing the human telomerase promoter (TERT) construct, P. Crespo for Ras and Raf expression vectors, M. Rosenfeld for pCMX-gal-NCoR, G. Piaggio and K. Katula for the cyclin B1 reporter, and K. W. Scotto for the MDR1 reporter plasmid.

Part of this work was supported by the Graduiertenkolleg 370 (F.G.). This work has been supported by grants from the Spanish Ministry of Education (SAF03-00801) and the Cooperative Cancer Network of the Spanish Ministry of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baniahmad, A., I. Ha, D. Reinberg, S. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and B. W. O'Malley. 1993. Interaction of human thyroid hormone receptor beta with transcription factor TFIIB may mediate target gene derepression and activation by thyroid hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 90:8832-8836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baniahmad, A., A. C. Kohne, and R. Renkawitz. 1992. A transferable silencing domain is present in the thyroid hormone receptor, in the v-erbA oncogene product and in the retinoic acid receptor. EMBO J. 11:1015-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baniahmad, A., C. Steiner, A. C. Kohne, and R. Renkawitz. 1990. Modular structure of a chicken lysozyme silencer: involvement of an unusual thyroid hormone receptor binding site. Cell 61:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baniahmad, A., D. Thormeyer, and R. Renkawitz. 1997. τ4/τc/AF-2 of the thyroid hormone receptor relieves silencing of the retinoic acid receptor silencer core independent of both τ4 activation function and full dissociation of corepressors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4259-4271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookes, S., J. Rowe, M. Ruas, S. Llanos, P. A. Clark, M. Lomax, M. C. James, R. Vatcheva, S. Bates, K. H. Vousden, D. Parry, N. Gruis, N. Smit, W. Bergman, and G. Peters. 2002. INK4a-deficient human diploid fibroblasts are resistant to RAS-induced senescence. EMBO J. 21:2936-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campos, E. I., K. J. Cheung, Jr., A. Murray, S. Li, and G. Li. 2002. The novel tumour suppressor gene ING1 is overexpressed in human melanoma cell lines. Br. J. Dermatol. 146:574-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, B., E. I. Campos, R. Crawford, M. Martinka, and G. Li. 2003. Analyses of the tumour suppressor ING1 expression and gene mutation in human basal cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 22:927-931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L., N. Matsubara, T. Yoshino, T. Nagasaka, N. Hoshizima, Y. Shirakawa, Y. Naomoto, H. Isozaki, K. Riabowol, and N. Tanaka. 2001. Genetic alterations of candidate tumor suppressor ING1 in human esophageal squamous cell cancer. Cancer Res. 61:4345-4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheung, K. J., Jr., and G. Li. 2001. The tumor suppressor ING1: structure and function. Exp. Cell Res. 268:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cong, Y. S., and S. Bacchetti. 2000. Histone deacetylation is involved in the transcriptional repression of hTERT in normal human cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275:35665-35668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimri, G. P., X. Lee, G. Basile, M. Acosta, G. Scott, C. Roskelley, E. E. Medrano, M. Linskens, I. Rubelj, O. Pereira-Smith, et al. 1995. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 92:9363-9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorman, C. M., and S. E. Johnson. 1999. Activated Raf inhibits avian myogenesis through a MAPK-dependent mechanism. Oncogene 18:5167-5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dressel, U., R. Renkawitz, and A. Baniahmad. 2000. Promoter specific sensitivity to inhibition of histone deacetylases: implications for hormonal gene control, cellular differentiation and cancer. Anticancer Res. 20:1017-1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du, J., B. Jiang, R. J. Coffey, and J. Barnard. 2004. Raf and RhoA cooperate to transform intestinal epithelial cells and induce growth resistance to transforming growth factor beta. Mol. Cancer Res. 2:233-241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feng, X., Y. Hara, and K. Riabowol. 2002. Different HATS of the ING1 gene family. Trends Cell Biol. 12:532-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garkavtsev, I., D. Demetrick, and K. Riabowol. 1997. Cellular localization and chromosome mapping of a novel candidate tumor suppressor gene (ING1). Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 76:176-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garkavtsev, I., I. A. Grigorian, V. S. Ossovskaya, M. V. Chernov, P. M. Chumakov, and A. V. Gudkov. 1998. The candidate tumour suppressor p33ING1 cooperates with p53 in cell growth control. Nature 391:295-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garkavtsev, I., A. Kazarov, A. Gudkov, and K. Riabowol. 1996. Suppression of the novel growth inhibitor p33ING1 promotes neoplastic transformation. Nat. Genet. 14:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garkavtsev, I., and K. Riabowol. 1997. Extension of the replicative life span of human diploid fibroblasts by inhibition of the p33ING1 candidate tumor suppressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:2014-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gozani, O., P. Karuman, D. R. Jones, D. Ivanov, J. Cha, A. A. Lugovskoy, C. L. Baird, H. Zhu, S. J. Field, S. L. Lessnick, J. Villasenor, B. Mehrotra, J. Chen, V. R. Rao, J. S. Brugge, C. G. Ferguson, B. Payrastre, D. G. Myszka, L. C. Cantley, G. Wagner, N. Divecha, G. D. Prestwich, and J. Yuan. 2003. The PHD finger of the chromatin-associated protein ING2 functions as a nuclear phosphoinositide receptor. Cell 114:99-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunduz, M., M. Ouchida, K. Fukushima, H. Hanafusa, T. Etani, S. Nishioka, K. Nishizaki, and K. Shimizu. 2000. Genomic structure of the human ING1 gene and tumor-specific mutations detected in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 60:3143-3146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunduz, M., M. Ouchida, K. Fukushima, S. Ito, Y. Jitsumori, T. Nakashima, N. Nagai, K. Nishizaki, and K. Shimizu. 2002. Allelic loss and reduced expression of the ING3, a candidate tumor suppressor gene at 7q31, in human head and neck cancers. Oncogene 21:4462-4470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hara, Y., Z. Zheng, S. C. Evans, D. Malatjalian, D. C. Riddell, D. L. Guernsey, L. D. Wang, K. Riabowol, and A. G. Casson. 2003. ING1 and p53 tumor suppressor gene alterations in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction. Cancer Lett. 192:109-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jager, D., E. Stockert, M. J. Scanlan, A. O. Gure, E. Jager, A. Knuth, L. J. Old, and Y. T. Chen. 1999. Cancer-testis antigens and ING1 tumor suppressor gene product are breast cancer antigens: characterization of tissue-specific ING1 transcripts and a homologue gene. Cancer Res. 59:6197-6204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson, R. A., T. A. Ince, and K. W. Scotto. 2001. Transcriptional repression by p53 through direct binding to a novel DNA element. J. Biol. Chem. 276:27716-27720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanaya, T., S. Kyo, K. Hamada, M. Takakura, Y. Kitagawa, H. Harada, and M. Inoue. 2000. Adenoviral expression of p53 represses telomerase activity through down-regulation of human telomerase reverse transcriptase transcription. Clin. Cancer Res. 6:1239-1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kataoka, H., P. Bonnefin, D. Vieyra, X. Feng, Y. Hara, Y. Miura, T. Joh, H. Nakabayashi, H. Vaziri, C. C. Harris, and K. Riabowol. 2003. ING1 represses transcription by direct DNA binding and through effects on p53. Cancer Res. 63:5785-5792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishnamurthy, J., K. Kannan, J. Feng, B. K. Mohanprasad, N. Tsuchida, and G. Shanmugam. 2001. Mutational analysis of the candidate tumor suppressor gene ING1 in Indian oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 37:222-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuzmichev, A., Y. Zhang, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and D. Reinberg. 2002. Role of the Sin3-histone deacetylase complex in growth regulation by the candidate tumor suppressor p33ING1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:835-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leonard, C., J. L. Huret, and Gfco. 2002. [From cytogenetics to cytogenomics of bladder cancers]. Bull. Cancer 89:166-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, A. W., M. Barradas, J. C. Stone, L. van Aelst, M. Serrano, and S. W. Lowe. 1998. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 12:3008-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malumbres, M., I. Pérez De Castro, María I. Hernández, María Jiménez, T. Corral, and A. Pellicer. 2000. Cellular response to oncogenic Ras involves induction of the Cdk4 and Cdk6 inhibitor p15INK4b. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2915-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manni, I., G. Mazzaro, A. Gurtner, R. Mantovani, U. Haugwitz, K. Krause, K. Engeland, A. Sacchi, S. Soddu, and G. Piaggio. 2001. NF-Y mediates the transcriptional inhibition of the cyclin B1, cyclin B2, and cdc25C promoters upon induced G2 arrest. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5570-5576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moore, M., N. Horikoshi, and T. Shenk. 1996. Oncogenic potential of the adenovirus E4orf6 protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 93:11295-11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nagashima, M., M. Shiseki, K. Miura, K. Hagiwara, S. P. Linke, R. Pedeux, X. W. Wang, J. Yokota, K. Riabowol, and C. C. Harris. 2001. DNA damage-inducible gene p33ING2 negatively regulates cell proliferation through acetylation of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci USA 98:9671-9676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naviaux, R. K., E. Costanzi, M. Haas, and I. M. Verma. 1996. The pCL vector system: rapid production of helper-free, high-titer, recombinant retroviruses. J. Virol. 70:5701-5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nouman, G. S., J. J. Anderson, S. Crosier, J. Shrimankar, J. Lunec, and B. Angus. 2003. Downregulation of nuclear expression of the p33(ING1b) inhibitor of growth protein in invasive carcinoma of the breast. J. Clin. Pathol. 56:507-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nouman, G. S., J. J. Anderson, J. Lunec, and B. Angus. 2003. The role of the tumour suppressor p33 ING1b in human neoplasia. J. Clin. Pathol. 56:491-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nouman, G. S., B. Angus, J. Lunec, S. Crosier, A. Lodge, and J. J. Anderson. 2002. Comparative assessment expression of the inhibitor of growth 1 gene (ING1) in normal and neoplastic tissues. Hybrid. Hybrid. 21:1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nourani, A., Y. Doyon, R. T. Utley, S. Allard, W. S. Lane, and J. Cote. 2001. Role of an ING1 growth regulator in transcriptional activation and targeted histone acetylation by the NuA4 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:7629-7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohmori, M., M. Nagai, T. Tasaka, H. P. Koeffler, T. Toyama, K. Riabowol, and J. Takahara. 1999. Decreased expression of p33ING1 mRNA in lymphoid malignancies. Am. J. Hematol. 62:118-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oki, E., Y. Maehara, E. Tokunaga, Y. Kakeji, and K. Sugimachi. 1999. Reduced expression of p33(ING1) and the relationship with p53 expression in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 147:157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oren, M. 1998. Tumor suppressors. Teaming up to restrain cancer. Nature 391:233-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmero, I., and M. Serrano. 2001. Induction of senescence by oncogenic Ras. Methods Enzymol. 333:247-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paramio, J. M., C. Segrelles, S. Ruiz, J. Martin-Caballero, A. Page, J. Martinez, M. Serrano, and J. L. Jorcano. 2001. The ink4a/arf tumor suppressors cooperate with p21cip1/waf in the processes of mouse epidermal differentiation, senescence, and carcinogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 276:44203-44211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson, M., R. Carbone, C. Sebastiani, M. Cioce, M. Fagioli, S. Saito, Y. Higashimoto, E. Appella, S. Minucci, P. P. Pandolfi, and P. G. Pelicci. 2000. PML regulates p53 acetylation and premature senescence induced by oncogenic Ras. Nature 406:207-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasheed, B. K., and S. H. Bigner. 1991. Genetic alterations in glioma and medulloblastoma. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 10:289-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saito, A., T. Furukawa, S. Fukushige, S. Koyama, M. Hoshi, Y. Hayashi, and A. Horii. 2000. p24/ING1-ALT1 and p47/ING1-ALT2, distinct alternative transcripts of p33/ING1. J. Hum. Genet. 45:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarela, A. I., S. M. Farmery, A. F. Markham, and P. J. Guillou. 1999. The candidate tumour suppressor gene, ING1, is retained in colorectal carcinomas. Eur. J. Cancer. 35:1264-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwarze, S. R., S. E. DePrimo, L. M. Grabert, V. X. Fu, J. D. Brooks, and D. F. Jarrard. 2002. Novel pathways associated with bypassing cellular senescence in human prostate epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277:14877-14883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serrano, M., A. W. Lin, M. E. McCurrach, D. Beach, and S. W. Lowe. 1997. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell 88:593-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimada, H., T. L. Liu, T. Ochiai, T. Shimizu, Y. Haupt, H. Hamada, T. Abe, M. Oka, M. Takiguchi, and T. Hiwasa. 2002. Facilitation of adenoviral wild-type p53-induced apoptotic cell death by overexpression of p33(ING1) in T.Tn human esophageal carcinoma cells. Oncogene 21:1208-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shinoura, N., Y. Muramatsu, M. Nishimura, Y. Yoshida, A. Saito, T. Yokoyama, T. Furukawa, A. Horii, M. Hashimoto, A. Asai, T. Kirino, and H. Hamada. 1999. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of p33ING1 with p53 drastically augments apoptosis in gliomas. Cancer Res. 59:5521-5528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Skowyra, D., M. Zeremski, N. Neznanov, M. Li, Y. Choi, M. Uesugi, C. A. Hauser, W. Gu, A. V. Gudkov, and J. Qin. 2001. Differential association of products of alternative transcripts of the candidate tumor suppressor ING1 with the mSin3/HDAC1 transcriptional corepressor complex. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8734-8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tokunaga, E., Y. Maehara, E. Oki, K. Kitamura, Y. Kakeji, S. Ohno, and K. Sugimachi. 2000. Diminished expression of ING1 mRNA and the correlation with p53 expression in breast cancers. Cancer Lett. 152:15-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toyama, T., and H. Iwase. 2004. p33ING1b and estrogen receptor(ER)alpha. Breast Cancer 11:33-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toyama, T., H. Iwase, P. Watson, H. Muzik, E. Saettler, A. Magliocco, L. DiFrancesco, P. Forsyth, I. Garkavtsev, S. Kobayashi, and K. Riabowol. 1999. Suppression of ING1 expression in sporadic breast cancer. Oncogene 18:5187-5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toyama, T., H. Iwase, H. Yamashita, Y. Hara, H. Sugiura, Z. Zhang, I. Fukai, Y. Miura, K. Riabowol, and Y. Fujii. 2003. p33(ING1b) stimulates the transcriptional activity of the estrogen receptor alpha via its activation function (AF) 2 domain. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 87:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Troppmair, J., J. Hartkamp, and U. R. Rapp. 1998. Activation of NF-kappa B by oncogenic Raf in HEK 293 cells occurs through autocrine recruitment of the stress kinase cascade. Oncogene 17:685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsang, F. C., L. S. Po, K. M. Leung, A. Lau, W. Y. Siu, and R. Y. Poon. 2003. ING1b decreases cell proliferation through p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. FEBS Lett. 553:277-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vieyra, D., R. Loewith, M. Scott, P. Bonnefin, F. M. Boisvert, P. Cheema, S. Pastyryeva, M. Meijer, R. N. Johnston, D. P. Bazett-Jones, S. McMahon, M. D. Cole, D. Young, and K. Riabowol. 2002. Human ING1 proteins differentially regulate histone acetylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277:29832-29839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xin, H., H. G. Yoon, P. B. Singh, J. Wong, and J. Qin. 2004. Components of a pathway maintaining histone modification and heterochromatin protein 1 binding at the pericentric heterochromatin in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:9539-9546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu, D., Q. Wang, A. Gruber, M. Bjorkholm, Z. Chen, A. Zaid, G. Selivanova, C. Peterson, K. G. Wiman, and P. Pisa. 2000. Downregulation of telomerase reverse transcriptase mRNA expression by wild type p53 in human tumor cells. Oncogene 19:5123-5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeremski, M., S. K. Horrigan, I. A. Grigorian, C. A. Westbrook, and A. V. Gudkov. 1997. Localization of the candidate tumor suppressor gene ING1 to human chromosome 13q34. Somat. Cell Mol. Genet. 23:233-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu, J., D. Woods, M. McMahon, and J. M. Bishop. 1998. Senescence of human fibroblasts induced by oncogenic Raf. Genes Dev. 12:2997-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]