Abstract

Background and aims

This study examined the prevalence of, and factors associated with, men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography.

Methods

Using an Internet-based data-collection procedure, we recruited 1,298 male pornography users to complete questionnaires assessing demographic and sexual behaviors, hypersexuality, pornography-use characteristics, and current interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography.

Results

Approximately 14% of men reported an interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography, whereas only 6.4% of men had previously sought treatment for use of pornography. Treatment-interested men were 9.5 times more likely to report clinically significant levels of hypersexuality compared with treatment-disinterested men (OR = 9.52, 95% CI = 6.72–13.49). Bivariate analyses indicated that interest-in-seeking-treatment status was associated with being single/unmarried, viewing more pornography per week, engaging in more solitary masturbation in the past month, having had less dyadic oral sex in the past month, reporting a history of seeking treatment for use of pornography, and having had more past attempts to either “cut back” or quit using pornography completely. Results from a binary logistic regression analysis indicated that more frequent cut back/quit attempts with pornography and scores on the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory – Control subscale were significant predictors of interest-in-seeking-treatment status.

Discussion and conclusions

Study findings could be used to inform current screening practices aimed at identifying specific aspects of sexual self-control, impulsivity, and/or compulsivity associated with problematic use of pornography among treatment-seeking individuals.

Keywords: hypersexuality, treatment-seeking men, pornography, sexual behaviors

Introduction

Pornography refers to written material or pictorial content of a sexually explicit nature that is intended to elicit sexual arousal in the reader or viewer. When surveyed, 30%–70% of heterosexual and gay/bisexual men report recreational use of pornography, whereas fewer women report viewing pornography recreationally (<10%) (Morgan, 2011; Ross, Mansson, & Daneback, 2012; Wright, 2013). Although watching pornography is a healthy sexual outlet for many individuals (Hald & Malamuth, 2008), some people report having difficulty managing their behavior. For these individuals, excessive/problematic use of pornography is characterized by craving, diminished self-control, social or occupational impairment, and use of sexually explicit material to cope with anxiety or dysphoric mood (Kor et al., 2014; Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015; Kraus, Potenza, Martino, & Grant, 2015; Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014). Problematic use of pornography is frequently reported by those seeking treatment for compulsive sexual behavior/hypersexuality (de Tubino Scanavino et al., 2013; Kraus, Potenza, et al., 2015; Morgenstern et al., 2011). For example, researchers found that excessive use of pornography (81%), compulsive masturbation (78%), and frequent casual/anonymous sex (45%) were among the most common behaviors reported by persons seeking treatment for hypersexuality (Reid et al., 2012).

Hypersexuality is more common among men (Kafka, 2010), and those seeking treatment are more likely to be Caucasian/white than from other ethnic/racial backgrounds (Farré et al., 2015; Kraus, Potenza, et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2012). Rates of hypersexuality among the general population are estimated around 3%–5%, with adult males comprising of the majority (80%) of affected persons (Kafka, 2010). Those seeking treatment for hypersexuality are more likely to meet the criteria for psychiatric comorbid disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression, substance use, and gambling) (>50%) (de Tubino Scanavino et al., 2013; Kraus, Potenza, et al., 2015; Raymond, Coleman, & Miner, 2003) and engage in HIV-risk behaviors (e.g., condomless anal sex and multiple sexual partners per occasion) (Coleman et al., 2010; Parsons, Grov, & Golub, 2012).

Currently, there is little consensus regarding the definition and symptom presentation of hypersexuality (Kingston, 2015). Excessive/problematic engagement in sexual behaviors has been considered as an impulsive–compulsive disorder (Grant et al., 2014), a feature of hypersexual disorder (HD) (Kafka, 2010), a non-paraphilic compulsive sexual behavior (Coleman, Raymond, & McBean, 2003), or as an addiction (Kor, Fogel, Reid, & Potenza, 2013). Multiple criteria proposed for HD share similarities with those for substance-use disorders (SUDs) (Kor et al., 2013; Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016). Specifically, SUDs (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and HD (Kafka, 2010) include diagnostic criteria assessing impaired control (i.e., unsuccessful attempts to moderate or stop a behavior, difficulty controlling urges/cravings) and risky use (i.e., use/behavior that leads to hazardous situations, e.g., overdose, engaging in condomless sex). HD and SUDs also include criteria used to assess social impairment linked to drug use or sexual behavior, respectively. However, SUD criteria assess physiological dependence (i.e., tolerance and withdrawal), whereas HD does not. In contrast, HD uniquely includes criteria measuring dysphoric mood states associated with excessive/problematic engagement in sexual behaviors.

Despite a successful field trial supporting the reliability and validity of criteria for HD (Reid et al., 2012), the American Psychiatric Association (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) rejected HD from DSM-5. Multiple concerns were raised about the lack of research including anatomical and functional imaging, molecular genetics, pathophysiology, epidemiology, and neuropsychological testing (Piquet-Pessôa, Ferreira, Melca, & Fontenelle, 2014), as well as the concern that HD could lead to forensic abuse or produce false positive diagnoses, given the absence of clear distinctions between normal range and pathological levels of sexual desires and behaviors (Moser, 2013; Wakefield, 2012; Winters, 2010). A recent review of the literature found clinical and neurobiological similarities between HD and SUDs; however, currently insufficient data are available, thus complicating classification, prevention and treatment efforts for researchers and clinicians (Kraus et al., 2016).

Currently, little is known about what factors are associated with individuals’ perceived need to seek treatment for untreated hypersexual behaviors – in this case, excessive/problematic use of pornography. To date, only one study has examined factors associated with men’s interest in seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography. Gola, Lewczuk, and Skorko (2016) found that negative symptoms (e.g., preoccupation, affect, and relationship disturbances because of sexual behaviors and impaired control) associated with problematic use of pornography were more robustly associated with treatment-seeking than quantity of pornography consumption. Although excessive/problematic use of pornography is commonly reported by those seeking treatment, little is known about the characteristics of these individuals. For example, it is not known which features (e.g., repeated failed attempts to quit, strong urges/cravings, and psychosocial impairments) are associated with desires for treatment seeking for excessive/problematic use of pornography. Are there specific features that might help to identify individuals who need and desire treatment for problematic use of pornography? Currently, screening practices and clinical interventions designed to ameliorate problems associated with excessive pornography use and untreated hypersexuality, in general, are lacking in the United States and abroad (Hook, Reid, Penberthy, Davis, & Jennings, 2014). Other factors such as religiosity and moral disapproval may also complicate the diagnosis and treatment of problematic use of pornography. For example, a recent study found that religiosity and moral disapproval of pornography statistically predicted “perceived addiction” to Internet pornography while being unrelated to the levels of use among young males using pornography (Grubbs, Exline, Pargament, Hook, & Carlisle, 2015). Understanding how factors such as religiosity/spirituality and moral disapproval affect individuals’ desire to seek treatment for possible hypersexual behavior remains poorly understood.

Using data from 1,298 male pornography users, this study sought to identify factors (e.g., demographics and sexual history characteristics) associated with individuals’ self-reported interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography. First, we examined what percentage of men would report a current interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography. We expected the rate to be relatively low because we recruited participants from a non-treatment seeking sample of men. Second, we investigated the prevalence of hypersexuality among our samples using the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI) (Reid, Garos, & Carpenter, 2011). We hypothesized that treatment-interested men would report significantly higher scores on the HBI than would treatment-disinterested men. Third, given the scarcity of data available in the literature, we explored whether any demographic and sexual-history factors distinguished between men who were interested or disinterested in treatment for the use of pornography. Specifically, we examined relationships between participant characteristics as a function of self-reported interest in treatment for use of pornography. We hypothesized that individuals interested in seeking treatment for pornography use would be more likely to report: (a) a higher weekly frequency and duration of use; (b) higher numbers of past attempts to either cut back or quit using pornography; and (c) higher frequency of solitary masturbation in the past month.

Methods

Procedure

Data were collected from 1,298 men recruited as part of a simultaneous investigation which investigates the psychometric properties of a questionnaire (Self-initiated Pornography Use-Reduction Strategies Self-Efficacy Questionnaire) designed to measure individuals’ self-efficacy to employ self-initiated cognitive-behavioral strategies intended to reduce their pornography use (Kraus, Rosenberg, & Tompsett, 2015). Criteria for inclusion were being male, being at least 18 years old, and having viewed pornography at least once in the previous 6 months. We posted a short description of the study during the months of June–July (2013) on several social media, psychology research, and health-related websites. The majority of the sample (88%) was recruited using notices posted on Craigslist® (i.e., a classified advertisement website with sections devoted to jobs, personals, and volunteer opportunities). The notices included a brief description of the study with a web link under the “Community Volunteer” section of Craigslist that includes requests for participation in research studies and non-research activities. The remaining 12% of respondents came from posting a brief description of the study and link on two psychology-based research sites (e.g., Psych Research and Psych Hanover) and other health-related websites (e.g., American Sexual Health Association).

We intentionally did not offer one or more large prizes as an incentive because we wanted to minimize the likelihood that non-users of pornography would participate in the study with hope of winning the prize. Therefore, as an incentive, we informed men that $2.00 would be donated to the American Cancer Society for every completed survey, with a maximum of a $150 donation. After consenting, men completed a series of questionnaires that were randomized to reduce order effects. An online survey tool randomized the order of all questionnaires for each participant with the exception of the demographic questionnaire, which came last.

Participants

Participant mean age was 34.4 years (SD = 13.1). Approximately 81% of men were from the United States, 8% were from Canada, and 11% were from other English-speaking countries (e.g., United Kingdom and Australia). Approximately 80% of men reported viewing pornography at least once a week or more.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

This questionnaire assessed participants’ demographic (e.g., age, marital status, and level of highest education) information.

Sexual questionnaires

We used a questionnaire employed in previous studies to measure participants’ sexual history (e.g., number of sexual partners, frequency of masturbation, and history of sexually transmitted infection) (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2016; Kraus, Rosenberg, et al., 2015; Rosenberg & Kraus, 2014).

Pornography history questionnaire

We used a questionnaire employed in previous studies to assess participants’ pornography history characteristics (e.g., frequency of pornography viewing, time spent watching pornography per week, number of attempts to “cut back” using pornography, and quit attempts for using pornography) (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2016; Kraus, Rosenberg, et al., 2015; Rosenberg & Kraus, 2014).

Hypersexual behavior inventory (HBI)

The HBI is a 19-item inventory that measures characteristics of hypersexuality – that is, engaging in sexual behavior in response to stress or dysphoric mood, repeated unsuccessful attempts to control sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors, and sexual behavior leading to impairment in functioning (Reid et al., 2011). Respondents rate how often they have experienced each sexual behavior (1 = never; 5 = very often). Scores on the HBI range from 19 to 95 with a score of 53 (or higher) suggesting the presence of a potential “hypersexual disorder.” HBI total and its subscales had excellent internal reliability (total = α = 0.95; coping α = 0.91; consequences α = 0.86; control α = 0.93).

Current interest in seeking treatment for pornography use

We assessed men’s current interest in seeking treatment for pornography use by asking them to indicate “yes” or “no” to the following question: “Would you like to seek professional help for your pornography use, BUT have not yet done so due to various reasons (e.g., shame, embarrassment, and not sure where to go).”

Past treatment for pornography use

We assessed participants’ past history of seeking treatment for pornography use by asking them to indicate “yes” or “no” to the following question: “Have you ever sought out professional help because of your use of pornography (by professional we mean seen a counselor, therapist, psychologist, and psychiatrist)?” For individuals who indicated “yes” for this question, they were asked how helpful was their treatment (“If yes, how helpful was the professional treatment you received?”) on a five-point scale (“not at all helpful,” “a little helpful,” “somewhat helpful,” “very helpful,” and “extremely helpful”).

Statistical analyses

We used SPSS-22 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0) for descriptive statistics, Mann–Whitney U test, Pearson chi-square test, and a binary logistic regression analysis. Our main hypotheses involve comparisons between treatment-interested and treatment-disinterested men. Two-sided tests and overall α level of 0.05 for all primary hypotheses were employed.

Ethics

All procedures in this study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Bowling Green State University approved the study. All participants were informed about the scope of the study and all provided written informed consent.

Results

Hypersexuality and pornography use characteristics in men stratified by interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography

Out of the 1,298 individuals surveyed, 14.3% (n = 186) reported a current interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography. Fewer men (6.4%, n = 83) reported having previously sought treatment for use of pornography, and on average, those who had received treatment rated it as only marginally helpful (M = 2.7, SD = 1.2). Of the 83 men who had previously sought treatment for use of pornography, 48.2% (n = 40) indicated they were currently interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography.

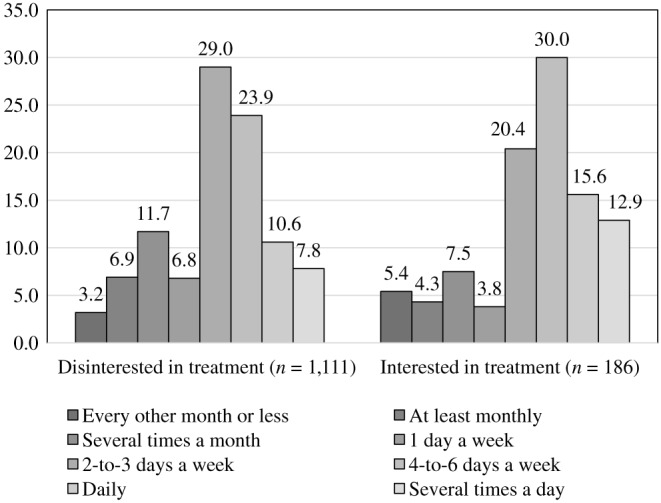

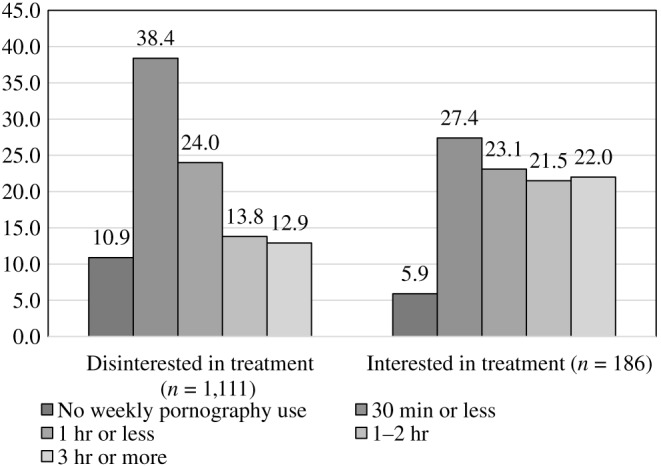

Using the whole sample, we found that mean scores for frequency of pornography use was 5.1 (SD = 1.8, skewness = −0.46, kurtosis = −0.34) and 1.9 (SD = 1.4, skewness = 0.86, kurtosis = 0.34) for amount of time spent each week watching pornography. Figures 1 and 2 show percentages for men’s use of pornography and amount of time they spent each week watching pornography by men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography.

Figure 1.

Percentages of men interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography by frequency of pornography use

Figure 2.

Percentages of men interested in seeking treatment for use of pornography by amount of time spent watching pornography

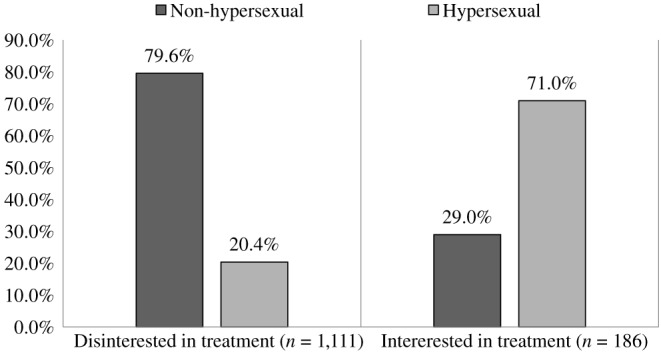

HBI scores were also calculated. Scores were as follows: HBI total (M = 43.2, SD = 17.9, skewness = 0.74, kurtosis = −0.13), coping (M = 17.6, SD = 7.4, skewness = 0.41, kurtosis = −0.61), consequences (M = 7.8, SD = 4.0, skewness = 1.2, kurtosis = 0.74), and control (M = 17.8, SD = 8.7, skewness = −0.46, kurtosis = −0.24). Approximately 28% (n = 359) of men scored at (or above) the suggested HBI total clinical cutoff (≥53) indicating the presence of a possible HD. As Figure 3 shows, men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography was positively associated with meeting or exceeding the HBI total clinical cutoff score [χ2 (1) = 203.27, p < 0.001, Cramer’s V = 0.40, OR = 9.52, 95% CI = 6.72–13.49].

Figure 3.

Percentages of men interested in treatment for use of pornography by HBI clinical cutoff score (≥53)

Demographic and sexual characteristics in men stratified by interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography

Although the skewness and kurtosis scores were within reason (±1.5) for continuous variables (reported above), we decided to conduct a Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K–S) test to determine whether we had a normal distribution for the sample. Results for the K–S test were significant (all ps < 0.001), indicating that the assumption of normal distribution was not met for the HBI total, HBI subscales, frequency of pornography use, and the amount of time spent each week watching pornography. Therefore, we used non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test) for the continuous variables, and employed Pearson chi-square tests for the categorical variables.

Analyses indicated that compared with treatment-disinterested men, treatment-interested men were more likely to be single and have had less dyadic oral sex (last 30 days), more “cut back” attempts with pornography, and more quit attempts with pornography. They were also more likely to have previously sought treatment for use of pornography, engaged in more solitary masturbation (last 30 days), and had higher scores on the HBI total and three subscales. We found no significant differences between treatment-interested and treatment-disinterested men for education level, living situation, sexual orientation, recent dyadic sexual activity (vaginal, anal, or mutual masturbation), history of sexually transmitted infections, and number of lifetime sexual intercourse partners (see Table 1 for complete details).

Table 1.

Demographic and sexual history factors associated with individuals’ interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography

| Interested in treatment for use of pornography | ||||

| Yes (n = 186) | No (n = 1,111) | |||

| Study characteristics | % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | χ2 / Z | p-Value |

| Age | 32.8 (11.6) | 34.6 (13.3) | 1.37 | 0.17 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, not currently dating | 37.1 | 29.3 | 9.27 | <0.05 |

| Some dating but not exclusive | 21.0 | 16.7 | ||

| Married/partnered | 41.9 | 54.0 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| High school graduate | 22.2 | 15.9 | 4.72 | 0.19 |

| Some college | 28.6 | 32.5 | ||

| Associate’s degree | 13.0 | 12.7 | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 36.2 | 38.8 | ||

| Living situation | ||||

| Alone | 21.6 | 21.5 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| With roommates | 17.3 | 17.6 | ||

| With partner/family members | 61.1 | 60.8 | ||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 70.3 | 71.8 | 0.25 | 0.88 |

| Gay | 11.6 | 11.7 | ||

| Bisexual | 18.0 | 16.5 | ||

| Country of origin | ||||

| USA | 78.0 | 81.7 | 1.76 | 0.41 |

| Canada | 10.8 | 8.1 | ||

| Other English speaking countries | 11.3 | 10.3 | ||

| Website recruitment | ||||

| Craigslist® | 91.9 | 87.4 | 3.10 | 0.08 |

| Other site | 8.1 | 12.6 | ||

| Sexually transmitted infection | ||||

| Yes | 11.3 | 15.2 | 1.95 | 0.18 |

| No | 88.7 | 84.8 | ||

| Lifetime sexual intercourse partners | ||||

| 10 or less partners | 58.1 | 53.3 | 3.75 | 0.15 |

| 11–20 partners | 18.3 | 24.6 | ||

| 30+ partners | 23.7 | 21.9 | ||

| Vaginal intercourse (past month) | ||||

| Yes | 48.1 | 55.2 | 3.21 | 0.08 |

| No | 51.9 | 44.8 | ||

| Anal intercourse (past month) | ||||

| Yes | 25.3 | 20.8 | 1.89 | 0.17 |

| No | 74.7 | 79.2 | ||

| Oral sex (past month) | ||||

| Yes | 54.6 | 63.5 | 5.29 | <0.05 |

| No | 45.5 | 36.5 | ||

| Mutual masturbation (past month) | ||||

| Yes | 46.7 | 54.0 | 3.35 | 0.08 |

| No | 53.3 | 46.0 | ||

| Past month masturbation | ||||

| 10 times or less | 31.0 | 36.8 | ||

| 11–20 times | 25.5 | 30.3 | 7.88 | <0.05 |

| 21+ times | 43.5 | 32.9 | ||

| Hypersexual Behavior Inventory | ||||

| HBI total scorea | 62.4 (17.8) | 40.0 (15.8) | 14.16 | <0.001 |

| HBI coping subscaleb | 22.7 (7.5) | 16.8 (7.1) | 9.50 | <0.001 |

| HBI consequences subscalec | 11.6 (4.5) | 7.1 (3.5) | 12.43 | <0.001 |

| HBI control subscaled | 28.1 (8.4) | 16.1 (7.5) | 15.23 | <0.001 |

| Ever sought treatment for porn | ||||

| Yes | 21.5 | 3.9 | 82.83 | <0.001 |

| No | 78.5 | 96.1 | ||

| Frequency of weekly pornography use | 5.5 (1.9) | 5.1 (1.8) | 3.68 | <0.001 |

| Amount of time spent watching porn each week | 2.4 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.3) | 4.95 | <0.001 |

| Cut back attempts with porn | ||||

| 0 attempts (“never”) | 12.9 | 65.5 | 216.04 | <0.001 |

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 40.9 | 23.4 | ||

| 4+ past attempts | 46.2 | 11.2 | ||

| Quit attempts with porn | ||||

| 0 attempts (“never”) | 25.3 | 75.0 | 251.05 | <0.001 |

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 34.4 | 19.2 | ||

| 4+ past attempts | 40.3 | 5.8 | ||

Note. Pearson chi-square test was used for dichotomous variables. Mann–Whitney U test (Z score) was used for continuous variables. Bold values represent statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Absolute range, 19–95.

Absolute range, 7–35.

Absolute range, 4–20.

Absolute range, 8–40.

Statistical predictors of men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography

Next, we conducted a binary logistic regression analysis to identify variables related to interest-in-seeking-treatment status. To reduce effects of Type I error, we entered into the model only variables significant at p < 0.001. The model was statistically significant, χ2 = 394.0, p < 0.001, with df = 10, and explained 46.7% (Nagelkerke’s R2) of the total variance. Classification was 43.5% of those interested in treatment; 96.6% for those disinterested in treatment; and total classification was 89.0%. As Table 2 displays significant predictors of interest-in-seeking-treatment status included 1-to-3 and 4+ “cut back” attempts with pornography, 4+ quit attempts with pornography, and scores on the HBI control subscale.

Table 2.

Statistical predictors of interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography

| Study characteristics | B | SE B | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Frequency of pornography use | 0.04 | 0.07 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) |

| Amount of time each week watching porn | 0.12 | 0.08 | 1.12 (0.96, 1.32) |

| Ever sought treatment for porn | 0.43 | 0.30 | 1.54 (0.86, 2.77) |

| Cutback attempts | |||

| 0 attempts | 1.61 | 0.30 | 1.00 |

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 1.43 | 0.36 | 4.98 (2.76, 8.99)* |

| 4+ past attempts | 4.18 (2.05, 8.55)* | ||

| Quit attempts | |||

| 0 attempts | 0.48 | 0.27 | 1.00 |

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 1.17 | 0.35 | 1.61 (0.95, 2.73) |

| 4+ past attempts | 3.23 (1.63, 6.38)* | ||

| HBI coping subscale | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) |

| HBI consequences subscale | 0.01 | 0.04 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) |

| HBI control subscale | 0.13 | 0.02 | 1.14 (1.10, 1.18)* |

Note. Logistic regression predicting likelihood of men’s expressed interest in seeking professional help for pornography use. Model summary: χ2 = 394.0, p < 0.001 with df = 10. Nagelkerke’s R2 = 46.7%. Classification: 43.5% of those wanting professional help; 96.6% those not wanting professional help; and total was 89.0%. Bold values represent statistically significant at p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Associations of select sexual-history variables by men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography by hypersexuality

In order to explore relationships between groups differing on hypersexuality and treatment-seeking status, men were categorized into four groups: (a) treatment-interested men with hypersexuality (n = 132); (b) treatment-disinterested men with hypersexuality (n = 227); (c) treatment-interested men without hypersexuality (n = 54); and lastly, (d) treatment-disinterested men without hypersexuality (n = 884). In an attempt to identify distinguishing clinical characteristics among these four groups, we conducted exploratory analyses with select sexual-history variables. As shown in Table 3, we found that treatment-interested men with hypersexuality masturbated more often and reported more past attempts to either cutback or quit using pornography completely compared with the other groups.

Table 3.

Select sexual-history factors associated with individuals’ interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography by hypersexual status

| Study characteristics | Tx-interested hypersexual (n = 132) | Tx-disinterested hypersexual (n = 227) | Tx-interested non-hypersexual (n = 54) | Tx-disinterested non-hypersexual (n = 884) | χ2/F | p-Value |

| % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | % / M (SD) | |||

| Sexual partners | 10.93 | 0.09 | ||||

| 10 or less partners | 53.8 | 48.0 | 68.5 | 54.6 | ||

| 11–20 partners | 20.5 | 26.0 | 13.0 | 24.5 | ||

| 30+ partners | 25.8 | 26.0 | 18.5 | 20.8 | ||

| Monthly masturbation | 15.89 | <0.05 | ||||

| 10 times or less | 28.2 | 32.4 | 37.1 | 38.0 | ||

| 11–20 times | 26.0 | 27.5 | 24.5 | 31.0 | ||

| 21+ times | 45.8 | 40.1 | 37.7 | 31.1 | ||

| Frequency of porn use | 5.7 (1.8)a | 5.6 (1.7)a | 4.9 (2.0)b | 4.9 (1.7)b | 14.12 | <0.001 |

| Amount of time watching pornography | 2.4 (1.2)d | 2.2 (1.2)d,c | 1.9 (1.2)c,e | 1.7 (1.2)e | 20.64 | <0.001 |

| Cut back attempts | 299.8 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 attempts (“never”) | 10.6 | 47.6 | 18.5 | 70.0 | ||

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 32.6 | 31.3 | 61.1 | 21.4 | ||

| 4+ past attempts | 56.8 | 21.1 | 20.4 | 8.6 | ||

| Quit attempts | 323.1 | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 attempts (“never”) | 22.0 | 56.8 | 33.3 | 79.6 | ||

| 1-to-3 past attempts | 30.3 | 29.1 | 44.4 | 16.6 | ||

| 4+ past attempts | 47.7 | 14.1 | 22.2 | 3.7 |

Note. Pearson chi-square test was used for dichotomous variables. One-way ANOVA was used for continuous variables.

Post hoc analyses (least significant difference) were conducted to denote where means were significantly different (p < 0.05). We used superscripts to indicate where means that were not statistically significant (p < 0.05). Bold values denote significance at p < 0.05.

Discussion

This study examined the prevalence of, and factors associated with, men’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography. The study found that approximately one of seven men reported a current interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography, but had not yet done so, possibly due to shame, embarrassment, or lack of knowledge regarding where to go for help. Fewer men in the study (6.4%) reported previously seeking treatment for use of pornography. We found that about half of those men who had previously sought treatment still expressed a desire for professional help, even though most indicated that the treatment was only marginally helpful.

Next, we examined reports of hypersexuality as measured on the HBI (Reid et al., 2011). As hypothesized, we found that treatment-interested men reported significantly higher scores on the HBI total and subscales compared with treatment-disinterested men. When using the suggested clinical-cut off score of 53 or higher on the HBI, we found that approximately 28% (n = 359) of all men screened positive for a possible HD. This rate is considerably higher than estimates of hypersexuality in the general population, which ranges from 3% to 5% for non-treatment-seeking men (Kafka, 2010). We believe our rate is much higher because of our recruitment method (i.e., online website study which targeted male pornography users) and should not be interpreted as reflecting regular pornography users in the general population. Current findings should not be interpreted as suggesting that 28% of all pornography users experience problems with hypersexuality; instead, our findings can only speak to the relationship between hypersexuality and problematic use of pornography that occurs in some individuals. As one example, we found that 71% of men who expressed an interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography met or exceeded the HBI clinical cutoff score. This finding suggests that, in general, men reporting an interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography were objectively reporting symptoms associated with hypersexuality.

We also explored whether any demographic and sexual-history factors distinguished between men who were interested or disinterested in treatment for the use pornography. Our hypotheses were supported. Specifically, we found that compared with treatment-disinterested men, treatment-interested men used more pornography (both frequency and duration), had more cut-back attempts with pornography, had more quit attempts with pornography, and engaged in higher rates of solitary masturbation in the past month. We also found men’s interest in treatment was associated with relationship status (single), frequency of oral sex within the last 30 days, and previous history of seeking treatment for use of pornography. Next, a binary logistic regression analysis found that 1-to-3 and 4+ “cut back” attempts with pornography, reporting 4+ quit attempts with pornography, and scores on the HBI control subscale were significant predictors of interest-in-seeking-treatment status. Lastly, we examined whether there were differences in clinical characteristics of men with and without hypersexuality by treatment-seeking-interest status. Specifically, we found that treatment-interested men masturbated more often and reported more past attempts to either cut back or quit using pornography completely compared with all other groups.

Overall, current findings suggest that interest in treatment may be explained, in part, by pornography users’ sense of “loss of control” over their sexual thoughts and behaviors related to pornography. Specifically, men interested in treatment reported behaviors (e.g., repeated failed attempts to either cut back or quit using pornography completely) and hypersexual symptoms (e.g., strong cravings and desires and intrusive sexual thoughts) associated with having difficulty regulating their use of pornography. Both SUD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and HD (Kafka, 2010) diagnostic criteria include impaired self-control, suggesting that problematic use of pornography may share similarities with other addictive behaviors. Poor impulse control is also a central feature of HD, which proposes that those affected by the condition experience numerous unsuccessful attempts to limit time spent engaging in sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors in response to dysphoric mood or stressful events (Kafka, 2010). Similar with another study (Gola et al., 2016), we found that impaired self-control over sexual behaviors could be an important consideration for persons interested in treatment for use of pornography and might be important to identify users who may require professional assistance. Moreover, the degree to which feeling “out of control” with one’s sexual behavior catalyzes pornography treatment-seeking behavior remains unexplored in the literature. Our findings suggest those behaviors such as repeated failed attempts to moderate or quit using pornography act as objective indicators for individuals who are weighing the pros/cons of seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography or other dysregulated sexual behaviors.

Additional research is needed to understand why 29% of men who reported an interest in treatment for use of pornography did not meet (or exceed) the suggestive cutoff on a measure of hypersexuality. Specifically, it would be important to understand whether additional factors (e.g., relationship status, level of religiosity, and personal values/beliefs) may relate to men’s self-reported interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography. In line with these possibilities, religiosity and moral disapproval of pornography statistically predicted perceived addiction to Internet pornography while being unrelated to levels of use among young males using pornography (Grubbs et al., 2015). Understanding what factors, both objective and subjective, contribute to one’s decision to seek help for problematic use of pornography or other problematic sexual behavers awaits future research.

Current findings have implications for clinical practice. Given frequent co-occurring psychiatric disorders among patients seeking treatment for problematic use of pornography (Kraus, Potenza, et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2012), developing effective screening practices to detect behaviors and psychological factors associated with perceived loss of control could be useful for identifying persons with untreated hypersexuality relating to pornography use. Public health awareness campaigns could focus on highlighting signs/symptoms associated with hypersexuality or problematic pornography viewing, since certain features appear linked to desire-for-treatment status. Additionally, designing screening items assessing for specific aspects of sexual self-control, impulsivity, and/or compulsivity may better inform approaches for engaging treatment-seeking patients, particularly those ambivalent about treatment (Reid, 2007).

One potential limitation of the current study includes the use of self-report measures to collect data on users’ demographic and sexual history characteristics and hypersexuality. Self-report data rely on individuals’ recollection of and willingness to disclose their sexual behaviors. However, using an Internet-based approach may have helped increase anonymity and reduced underreporting by study participants; however, this possibility remains speculative. The use of cross-sectional data cannot speak to causation or directionality of associations observed. Findings may also not generalize to individuals wanting treatment for other kinds of hypersexual behaviors (e.g., frequent casual/anonymous sex, compulsive masturbation, and paid sex). In addition, this study did not include women. Although HD is more typically reported in men, hypersexual women report high masturbation frequency, number of sexual partners, and use of pornography (Klein, Rettenberger, & Briken, 2014). Currently, additional research is needed to study the prevalence of, and factors associated with, women’s interest in seeking treatment for use of pornography or other hypersexual behaviors. A final limitation of the current study is that we did not measure race/ethnicity of participants, but instead, asked about their country of residence. Limited data suggest that individuals seeking treatment for hypersexuality may be more likely among white/Caucasian individuals compared with other groups (Farré et al., 2015; Kraus, Potenza, et al., 2015; Reid et al., 2012); however, caution is advised given the lack of available epidemiological data and because sociodemographic or racial/ethnic differences reported elsewhere may be explained, in part, by other factors such as having access to treatment providers (Kraus et al., 2016). Future research should include variables assessing race/ethnicity because their relationships with interest in treatment for problematic use of pornography or hypersexuality are unclear.

Conclusions

This study identified features in men associated with self-reported interests in seeking treatment for use of pornography. Additional research is needed to examine these features among women and persons reporting problems with other types of sexual behaviors (e.g., paid sex and anonymous sex). Future research is needed to identify possible barriers to care (e.g., treatment availability, financial means, psychological factors relating to shame and embarrassment, and perceived stigma) and facilitators for treatment engagement for those interested in obtaining help managing their use of pornography.

Authors’ contribution

SWK (Principal Investigator) contributed to the initial study design, data collection, interpretation of the results, and drafted the manuscript. SM and MNP contributed to the interpretation of results, manuscript development, and final draft approval. SWK had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest with respect to the content of this manuscript. SWK and SM have no relationships to disclose. MNP has consulted for and advised Ironwood, Lundbeck, INSYS, Shire, and RiverMend Health, and has received research support from Mohegan Sun Casino, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, and Pfizer, but none of these entities supported the current research.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, VISN 1 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, the National Center for Responsible Gaming, and CASAColumbia. SWK and SM are full-time employees of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views of the funding agencies and reflect the views of the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM 5. Arlington, VA: bookpointUS. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E., Horvath K. J., Miner M., Ross M. W., Oakes M., Rosser B. R. S., Men’s INTernet Sex (MINTS-II) Team (2010). Compulsive sexual behavior and risk for unsafe sex among internet using men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(5), 1045–1053. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9507-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E., Raymond N., McBean A. (2003). Assessment and treatment of compulsive sexual behavior. Minnesota Medicine, 86(7), 42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Tubino Scanavino M., Ventuneac A., Abdo C. H. N., Tavares H., do Amaral M. L. S., Messina B., dos Reis S. C., Martins J. P. L. B., Parsons J. T. (2013). Compulsive sexual behavior and psychopathology among treatment-seeking men in São Paulo, Brazil. Psychiatry Research, 209(3), 518–524. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farré J. M., Fernández-Aranda F., Granero R., Aragay N., Mallorquí-Bague N., Ferrer V., More A., Bouman W. P., Arcelus J., Savvidou L. G., Penelo E., Aymamí M. N., Gómez-Peña M., Gunnard K., Romaguera A., Menchón J. M., Vallès V., Jimenez-Murcia S. (2015). Sex addiction and gambling disorder: Similarities and differences. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 56, 59–68. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gola M., Lewczuk K., Skorko M. (2016). What matters: Quantity or quality of pornography use? Psychological and behavioral factors of seeking treatment for problematic pornography use. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 815–824. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J. E., Atmaca M., Fineberg N. A., Fontenelle L. F., Matsunaga H., Janardhan Reddy Y. C., Simpson H. B., Thomsen P. H., van den Heuvel O. A., Veale D., Woods D. W., Stein D. J. (2014). Impulse control disorders and “behavioural addictions” in the ICD-11. World Psychiatry, 13, 125–127. doi:10.1002/wps.20115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs J. B., Exline J. J., Pargament K. I., Hook J. N., Carlisle R. D. (2015). Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 125–136. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hald G. M., Malamuth N. M. (2008). Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(4), 614–625. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9212-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook J. N., Reid R. C., Penberthy J. K., Davis D. E., Jennings D. J., II. (2014). Methodological review of treatments for nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 40(4), 294–308. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.751075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafka M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. doi:10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston D. A. (2015). Debating the conceptualization of sex as an addictive disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 2, 195–201. doi:10.1007/s40429-015-0059-6 [Google Scholar]

- Klein V., Rettenberger M., Briken P. (2014). Self‐reported indicators of hypersexuality and its correlates in a female online sample. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(8), 1974–1981. doi:10.1111/jsm.12602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kor A., Fogel Y., Reid R. C., Potenza M. N. (2013). Should hypersexual disorder be classified as an addiction? Sex Addict Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 27–47. doi:10.1080/10720162.2013.768132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kor A., Zilcha-Mano S., Fogel Y. A., Mikulincer M., Reid R. C., Potenza M. N. (2014). Psychometric development of the problematic pornography use scale. Addictive Behaviors, 39(5), 861–868. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S. W., Meshberg-Cohen S., Martino S., Quinones L. J., Potenza M. N. (2015). Treatment of compulsive pornography use with naltrexone: A case report. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(12), 1260–1261. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15060843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S. W., Potenza M. N., Martino S., Grant J. E. (2015). Examining the psychometric properties of the Yale-Brown obsessive–compulsive scale in a sample of compulsive pornography users. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 59, 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S., Rosenberg H. (2014). The pornography craving questionnaire: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(3), 451–462. doi:10.1007/s10508-013-0229-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S. W., Rosenberg H. (2016). Lights, camera, condoms! Assessing college men’s attitudes toward condom use in pornography. Journal of American College Health, 64(2), 1–8. doi:10.1080/07448481.2015.1085054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S. W., Rosenberg H., Tompsett C. J. (2015). Assessment of self-efficacy to employ self-initiated pornography use-reduction strategies. Addictive Behaviors, 40, 115–118. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus S. W., Voon V., Potenza M. N. (2016). Should compulsive sexual behavior be considered an addiction? Addiction. Advance online publication. doi:10.1111/add.13297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan E. M. (2011). Associations between young adults’ use of sexually explicit materials and their sexual preferences, behaviors, and satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 48(6), 520–530. doi:10.1080/00224499.2010.543960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J., Muench F., O’Leary A., Wainberg M., Parsons J. T., Hollander E., Blain L., Irwin T. (2011). Non-paraphilic compulsive sexual behavior and psychiatric co-morbidities in gay and bisexual men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18(3), 114–134. doi:10.1080/10720162.2011.593420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser C. (2013). Hypersexual disorder: Searching for clarity. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 48–58. doi:10.1080/10720162.2013.775631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J. T., Grov C., Golub S. A. (2012). Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. American Journal of Public Health, 102(1), 156–162. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquet-Pessôa M., Ferreira G. M., Melca I. A., Fontenelle L. F. (2014). DSM-5 and the decision not to include sex, shopping or stealing as addictions. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 172–176. doi:10.1007/s40429-014-0027-6 [Google Scholar]

- Raymond N. C., Coleman E., Miner M. H. (2003). Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44(5), 370–380. doi:10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid R. C. (2007). Assessing readiness to change among clients seeking help for hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 14(3), 167–186. doi:10.1080/10720160701480204 [Google Scholar]

- Reid R. C., Carpenter B. N., Hook J. N., Garos S., Manning J. C., Gilliland R., Cooper E. B., McKittrick H., Davtian M., Fong T. (2012). Report of findings in a DSM‐5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(11), 2868–2877. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02936.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid R. C., Garos S., Carpenter B. N. (2011). Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the hypersexual behavior inventory in an outpatient sample of men. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18(1), 30–51. doi:10.1080/10720162.2011.555709 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H., Kraus S. (2014). The relationship of “passionate attachment” for pornography with sexual compulsivity, frequency of use, and craving for pornography. Addictive Behaviors, 39(5), 1012–1017. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross M. W., Mansson S. A., Daneback K. (2012). Prevalence, severity, and correlates of problematic sexual Internet use in Swedish men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(2), 459–466. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9762-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield J. C. (2012). The DSM-5’s proposed new categories of sexual disorder: The problem of false positives in sexual diagnosis. Clinical Social Work Journal, 40(2), 213–223. doi:10.1007/s10615-011-0353-2 [Google Scholar]

- Winters J. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A more cautious approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(3), 594–596. doi:10.1007/s10508-010-9607-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright P. J. (2013). US males and pornography, 1973–2010: Consumption, predictors, correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 50(1), 60–71. doi:10.1080/00224499.2011.628132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]