Abstract

Background and aims

Pathological gambling is associated with comorbid disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and drug and alcohol abuse. Difficulties of emotion regulation may be one of the factors related to the presence of addictive disorders, along with comorbid symptomatology in pathological gamblers. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the difficulties of emotion regulation, drug and alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology in pathological gamblers, and the mediating role of difficulties of emotion regulation between anxiety and pathological gambling.

Methods

The study sample included 167 male pathological gamblers (mean age = 39.29 years) and 107 non-gamblers (mean age = 33.43 years). Pathological gambling (SOGS), difficulties of emotion regulation (DERS), drug and alcohol abuse (MUTICAGE CAD-4), and anxious and depressive symptomatology (SA-45) were measured. Student’s t, Pearson’s r, stepwise multiple linear regression and multiple mediation analyses were conducted. The study was approved by an Investigational Review Board.

Results

Relative to non-gamblers, pathological gamblers exhibited greater difficulties of emotion regulation, as well as more anxiety, depression, and drug abuse. Moreover, pathological gambling correlated with emotion regulation difficulties, anxiety, depression, and drug abuse. Besides, emotion regulation difficulties correlated with and predicted pathological gambling, drug and alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology. Finally, emotion regulation difficulties mediated the relationship between anxiety and pathological gambling controlling the effect of age, both when controlling and not controlling for the effect of other abuses.

Discussion and conclusions

These results suggest that difficulties of emotion regulation may provide new keys to understanding and treating pathological gambling and comorbid disorders.

Keywords: pathological gambling, drugs, alcohol, emotion regulation, anxiety, depression

Introduction

Pathological gambling is a behavioral addiction that is often accompanied by other disorders, such as anxious and depressive disorders, and drug and alcohol abuse (Barnes, Welte, Tidwell, & Hoffman, 2015; el-Guebaly et al., 2006; Griffiths, Wardle, Orford, Sproston, & Erens, 2011; Petry, 2007). Lorains, Cowlishaw, and Thomas (2011) conducted a meta-analysis in which they found that 57.5% of gamblers had a comorbid substance use disorder. This study also showed that 37.9% of gamblers suffered from a mood disorder, whereas 37.4% had anxiety disorders. Gambling and substance use disorders are related, with similarities at clinical, phenomenological, and biological levels (Wareham & Potenza, 2010). According to Problem-Behavior Theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), potentially harmful behaviors often co-occur, partly, because they share internal and external characteristics that would cause those behaviors.

Emotional disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are associated with concurrent difficulties in emotion regulation (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema & Schweizer, 2010; Hofmann, Sawyer, Fang, & Asnaani, 2012), that is, the process by which individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience these emotions (Gross, 2013). Emotion regulation is proving to be a central concept in most psychological disorders because difficulties in emotion regulation are related to their etiology and maintenance (Bradley, 2000). It has been suggested that emotion regulation may constitute a common transdiagnostic factor among all of them (Kring & Sloan, 2009; Trosper, Buzzella, Bennett, & Ehrenreich, 2009). Emotion dysregulation is also closely related to impulsive behaviors. Authors such as Schreiber, Grant, and Odlaug (2012) have noted that high punctuations in impulsivity are associated with greater difficulties in regulating emotions. In particular, pathological gamblers have been shown to have difficulties in emotion regulation in clinical samples (Estévez, Herrero, Sarabia, & Jauregui, 2014; Williams, Geisham, Eerskine, & Cassedy, 2012) although few studies exist on the topic. Emotion regulation has also been related to drug abuse (Weiss, Tull, Anestis, & Gratz, 2013), alcohol (Fox, Hong, & Sinha, 2008), and other impulsive behaviors such as binge eating (Whiteside et al., 2007), problematic internet use (Caplan, 2010), or risky sexual behavior (Messman-Moore, Walsh, & DiLillo, 2010).

It has been suggested that emotion regulation might be one of the factors that explains the presence of addictive disorders. Pathological gambling has been related to the expectancy of obtaining positive affective states or alleviating negative affective states through gambling (Shead, Callan, & Hodgins, 2008). Khantzian (1985) proposed that substance use could be a way of self-medication for its use may alleviate distress; therefore, aversive emotional states may predispose one to substance abuse (Colder, 2001; Robinson, Sareen, Cox, & Bolton, 2009). Drug intoxication, for example, may be a form of emotion regulation because substances may partly be used as a means of regulating one’s present emotional state, i.e., heightening positive affect, alleviating or improving negative affect, or reducing cravings (Kober & Bolling, 2014). Many models have followed this idea and considered that one’s desire to alter his/her mood may underlie addictive behavior (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1990; Simons, Gaher, Correia, Hansen, & Christopher, 2005). The same idea has been applied to pathological gambling (Stewart & Zack, 2008). Additionally, it has been found that individuals with both pathological gambling and another comorbid addictive disorder performed both addictive behaviors due to the same motives (Stewart, Zack, Collins, & Klein, 2008).

As noted, pathological gambling and alcohol and drug abuse are related to the presence of anxious and depressive symptomatology, as well as difficulties in emotion regulation. According to Tice, Bratslavsky, and Baumeister (2001), negative emotional states can lead to impulsive behaviors such as gambling, alcohol or drug use, as a way of regulating negative emotions and as a consequence of failures in self-control. In the same line, Weiss, Tull, Viana, Anestis, and Gratz (2012) found that difficulties in emotion regulation mediated the relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and impulsive behaviors. These authors suggested that impulsive behaviors are associated with maladaptive responses to emotions or difficulties controlling behaviors in the presence of emotional distress. In the case of pathological gambling, the only similar study is the one conducted by Estévez et al. (2014), which showed that difficulties in emotion regulation may be mediators of the relationship between pathological gambling, internet and mobile abuse, and dysfunctional psychological symptomatology in young adults and adolescents. However, adolescence is a period of emotional development (Silk, Steinberg, & Morris, 2003), so these results could be different in other age ranges. Additionally, in that study, the effect of other addictions was not measured, what may have affected to the results.

Therefore, this study had three primary aims. First, we aimed to measure the differences in emotion regulation and anxious and depressive symptomatology as a function of the presence or absence of pathological gambling. Second, we aimed to analyze the relationship and predictive role of emotion regulation with pathological gambling, drug and alcohol abuse, and depressive and anxious symptomatology. Finally, our third aim was to analyze the mediating role of emotion regulation between anxious and depressive symptomatology and pathological gambling, measuring the effect of drug and alcohol abuse.

Methods

Participants

The study sample contained 274 participants from centers of treatment for pathological gambling, mostly associated with FEJAR (Spanish Federation of Rehabilitated Gamblers), as well as social networks and university centers. Participants also had to be greater than 18 years of age to be eligible for the study. The sample was divided into two subsamples. Individuals who were rated as pathological gamblers on the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS; Lesieur & Blume, 1987) and came from centers for treatment for pathological gambling were included in the group of pathological gamblers. The other group comprised individuals who scored as non-gamblers and came from universities and social networks. Finally, to balance the groups, women were excluded because only 7 women with pathological gambling were recruited compared to 211 women in the non-gambler group. The group with pathological gambling consisted of 167 male participants between 18 and 69 years of age and the group without pathological gambling consisted of 107 male participants between 18 and 69 years of age. The sociodemographic data for the two subsamples are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of sociodemographic data between pathological gamblers and non-gamblers

| Age | Employment status | |||||

| M(SD) | Active workers | Unemployed | Retired | Students | Active working students | |

| Pathological gamblers (n = 167) | 39.29(11.84) | 51.3% | 27.2% | 8.2% | 10.7% | 2.5% |

| Non-gamblers (n = 107) | 33.43(11.93) | 49.1% | 10.4% | 0% | 28.4% | 13.2% |

| Education level | Marital status | |||||||||

| No studies | Primary studies | Secondary studies | Professional training | University studies | Single | Married | Separated/divorced | Common-law partnership | Widower | |

| Pathological gamblers (n = 167) | 12% | 18% | 25.7% | 32.3% | 12% | 45.2% | 32.5% | 10.2% | 11.4% | 0.6% |

| Non-gamblers (n = 107) | 0% | 1.9% | 4.7% | 34.6% | 58.9% | 69.2% | 22.4% | 1.9% | 6.5% | 0% |

Measures

Pathological gambling

Pathological gambling was assessed by the SOGS (Lesieur & Blume, 1987). The Spanish version was adapted by Echeburúa, Báez, Fernández-Montalvo, and Páez (1994). The SOGS is a tool for screening pathological gambling that was developed for clinical populations, containing 32 items. Scores above 4 points suggest the probable presence of pathological gambling. Regarding its reliability, the SOGS has high internal consistency, with a Cronbach α of .94. Moreover, its test–retest reliability over an interval of 4 weeks was .98 (p < .001), and the convergent validity with the DSM-IV criteria was .94. In this study, Cronbach’s α for the SOGS was .91.

Drug and alcohol abuse

The MULTICAGE CAD-4 (Pedrero-Pérez et al., 2007) is a measure of impulsivity and addictive behavior, with or without substance use, including pathological gambling, alcohol abuse or dependency, substance addiction, eating disorders, addiction to the internet, addiction to video games, compulsive shopping, and addiction to sex. It contains 32 items. The internal consistency of the MULTICAGE CAD-4 is satisfactory (Cronbach’s α for the total scale = .86 while subscales show values greater than .70). The test–retest reliability over 20 days is r = .89. The criterion validity is also adequate (it detects between 90 and 100% of cases already diagnosed). In this study, the alcohol (Cronbach’s α = .77) and drugs (Cronbach’s α = .85) subscales were used.

Emotion regulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, 2004) was used to measure emotion dysregulation through the analysis of different deficits that may affect optimal emotional regulation. We used the Spanish version of the DERS in this study (Hervás & Jódar, 2008). The total number of items was reduced (28 items) in the Spanish version compared to the original version (36 items). Items were rated along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Almost never/0–10% of the time” to “Almost always/90–100% of the time.” The distribution of items on the Spanish version was also different; specifically, the original version comprised six factors while the Spanish adaptation had five factors. Factors included: 1) Lack of emotional awareness: reflects an inattention to, and lack of awareness of, emotional responses; 2) Non-acceptance of emotional responses: reflects a tendency to have negative secondary emotional responses to one’s negative emotions, or nonaccepting reactions to one’s distress; 3) Lack of emotional clarity: reflects the extent to which individuals know (and are clear about) the emotions they are experiencing; 4) Difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior: reflects difficulties concentrating and accomplishing tasks when experiencing negative emotions; and 5) Lack of emotional control: reflects difficulties remaining in control of one’s behavior when experiencing negative emotions and the belief that there is little that can be done to regulate emotions effectively, once an individual is upset. The level of internal consistency of the DERS is optimal, with a Cronbach α of .93 for the total scale and ranging from .73 and .91 for the others. Moreover, test–retest reliability measured in a lapse of 6 months was adequate, indicating a good temporal stability (Hervás & Jódar, 2008). In this study, the Cronbach α was .94 for the overall scale and ranged from .79 and .93 in the five subscales.

Anxious and depressive symptomatology

Anxious and depressive symptomology was assessed using the Anxiety and Depression subscales of the Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire (SA-45; Davison et al., 1997), a short version of the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90-R; Derogatis, 2002), which was adapted into Spanish by Sandín, Valiente, Chorot, Santed, and Lostao (2008). It is an instrument for evaluating psychopathological symptomatology. On the SA-45, participants indicate the degree to which each of the 45 symptoms had been present during the last week along a Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Nothing at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”). The questionnaire measures the following nine factors: depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, psychoticism, paranoid ideation, and obsessive-compulsivity. In this study, two subscales were used, Anxiety and Depression. The SA-45 has high internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α of .95 for the total scale, .85 for the Depression subscale, and .84 for the Anxiety subscale. Moreover, the convergent validity and discriminant validity are adequate. In this study, Cronbach’s α was .83 in the Depression subscale and .84 in the Anxiety subscale.

Procedure

Participants were recruited to this study in different ways. Pathological gamblers, who were in treatment at the time of their participation (average months in treatment = 3.36), were recruited from centers and associations for the treatment of pathological gambling, where gamblers in treatment were invited to participate. Non-gamblers were recruited from university centers (12.1%) and social networks (87.9%). Participants completed a questionnaire, in either an online or offline format. In both cases, the questionnaire contained a cover letter that included an explanation of the study, its aims, the voluntary nature of participation, informed consent, and the confidentiality and anonymity of the obtained data. Contact details for the researchers were also provided.

Statistical analysis

A cross-sectional correlational analysis was conducted. All analyses were conducted in SPSS 22. First, Student’s t was used to measure the differences between gamblers and non-gamblers in pathological gambling, emotion regulation difficulties, anxiety, depression, drug abuse, and alcohol abuse. Effect sizes of identified differences were measured by using Cohen’s d, where a value lower than .20 indicates a small effect size, near .50 indicates a moderate effect size, and above .80 indicates a high effect size (Cohen, 1992). Second, correlation coefficients were calculated among all the variables by using Pearson’s r in the group of pathological gamblers. Third, stepwise multiple linear regression analyses were conducted in this group to evaluate the predictive role of difficulties in emotion regulation relative to pathological gambling, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology.

Second, after bivariate relationships were verified between the variables in the case of anxiety but not in the case of depression, a mediation analysis was conducted to analyze how the independent variable X (anxiety) affects the dependent variable Y (pathological gambling) through multiple mediators M (lack of emotional awareness; non-acceptance of emotional responses; lack of emotional clarity; difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior; lack of emotional control) in the group of pathological gamblers. The analysis was conducted by using bootstrapping, which is an adequate technique for multiple mediation models and can be used in small and moderate samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Two separate models were examined using the macro INDIRECT for SPSS (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). First model included the subscales of Drugs and Abuse of the MULTICAGE (Pedrero-Pérez et al., 2007) as covariates to control for their potential effects in the relationship, and a second model did not include them. Age was included as a covariate in both models, in order to control its effect on the relationship. First, the significance of the effect of the independent variable on the mediator variables (a-path) and the effect of mediator variables on the dependent variable (b-path) was tested. Then, the total effect of X on Y along with the mediator variables (c-path) and the direct effect of X on Y while controlling for the effect of mediator variables (c’-path) were measured. Second, the indirect effect of the mediator variables was measured by bootstrapping with a sample of 5000 bootstraps, and the indirect effect of each mediator variable on the relationship between X and Y was analyzed.

Ethics

The study procedures were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of the University of Deusto approved the study. All subjects were informed about the study and all provided informed consent.

Results

First, mean differences were measured between pathological gamblers and non-gamblers in pathological gambling, emotion regulation, anxiety, depression, drug abuse, and alcohol abuse (Table 2). The results indicate that the differences were significant for all variables except alcohol. According to Cohen’s criterion (1992), the effect sizes were medium for drug abuse, anxiety, depression, lack of awareness, lack of clarity, and difficulties in goal-oriented behavior while effect sizes were high for non-acceptance, lack of control, total emotion dysregulation, and pathological gambling.

Table 2.

Comparison between pathological gamblers and non-gamblers in pathological gambling, emotion regulation, drug and alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology

| Pathological gamblers (n = 167) | Non-gamblers (n = 107) | |||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t(df) | d | |

| 1. Pathological gambling | 10.77 | 3.36 | .47 | .76 | 38.12(191.38)* | 4.23 |

| 2. Lack of awareness | 10.85 | 4.07 | 9.30 | 3.66 | 3.13(259)** | .40 |

| 3. Non-acceptance | 20.14 | 7.99 | 12.89 | 6.27 | 8.00(242.15)* | 1.00 |

| 4. Lack of clarity | 9.43 | 3.87 | 7.08 | 2.65 | 5.77(252.97)* | .71 |

| 5. Goal-oriented behavior | 10.77 | 4.39 | 9.31 | 3.73 | 2.85(242.88)** | .36 |

| 6. Lack of control | 20.26 | 14.80 | 8.72 | 6.02 | 5.78(241.96)* | 1.02 |

| 7. Total emotion reg. | 71.44 | 21.86 | 52.06 | 15.62 | 7.6(213.65)* | 1.02 |

| 8. Alcohol | 1.07 | 1.42 | 1.24 | 1.20 | −1.01(247.9) | −.13 |

| 9. Drugs | .83 | 1.36 | .28 | .76 | 4.01(232.8)* | .50 |

| 10. Anxiety | 5.25 | 4.32 | 3.60 | 3.70 | 3.27(239.9)** | .41 |

| 11. Depression | 6.65 | 5.11 | 3.94 | 3.33 | 5.15(255.93)* | .63 |

Total emotion reg. = Total emotion dysregulation.

p < .001.

p < .01.

The correlations among pathological gambling, emotion regulation, anxiety, depression, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse were then analyzed in the group of gamblers (Table 3). Difficulties of emotion regulation were found to correlate with all of these variables. Alcohol abuse and drug abuse correlated positively and significantly with difficulties of emotion regulation as well as with one another; drug abuse also correlated with depression, anxiety, and pathological gambling, while alcohol did not. Anxiety and depression correlated significantly with all of these variables except for lack of awareness and alcohol abuse, although depression did not correlate with pathological gambling.

Table 3.

Correlations among emotion regulation difficulties, pathological gambling, anxiety, depression, alcohol, and drugs in gamblers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1. Lack of awareness | — | |||||||||

| 2. Non-acceptance | −.07 | — | ||||||||

| 3. Lack of clarity | .43** | .43** | — | |||||||

| 4. Goal-oriented behavior | −.04 | .59** | .36** | — | ||||||

| 5. Lack of control | .00 | .68** | .49** | .78** | — | |||||

| 6. Total emotion dysregulation | .23** | .83** | .69** | .79** | .90** | — | ||||

| 7. Pathological gambling | −.08 | .26** | .05 | .15 | .25** | .22** | — | |||

| 8. Depression | .06 | .52** | .48** | .50** | .52** | .60** | .10 | — | ||

| 9. Anxiety | −.03 | .51** | .41** | .50** | .58** | .59** | .23** | .68** | — | |

| 10. Alcohol | .05 | .17* | .16 | .19* | .29* | .26** | .09 | .07 | .14 | — |

| 11. Drugs | .02 | .15 | .13 | .19* | .22* | .22** | .19* | .22* | .17* | .52** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Stepwise multiple linear regression analyses were also conducted to evaluate the predictive role of difficulties in emotion regulation relative to pathological gambling, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology. The results showed that difficulties in emotion regulation were predictive of all of these variables (Table 4).

Table 4.

Linear multiple regression of difficulties of emotion regulation and depression, anxiety, pathological gambling, drugs, and alcohol

| Depression (R = .63, R2 = .39, adjusted R2 = .38, p = .00) | B | β | t | Sig. |

| Non-acceptance | .18 | .28 | 3.33 | .00* |

| Lack of clarity | .36 | .27 | 3.66 | .00* |

| Goal-oriented behavior | .29 | .24 | 3.02 | .00* |

| Anxiety (R = .60, R2 = .36, adjusted R2 = .35, p = .00) | B | β | t | Sig. |

| Lack of control | .21 | .43 | 4.75 | .00* |

| Non-acceptance | .12 | .22 | 2.46 | .02** |

| Pathological gambling (R = .26, R2 = .07, adjusted R2 = .06, p = .00) | B | β | t | Sig. |

| Non-acceptance | .11 | .26 | 3.26 | .00* |

| Drugs (R = .24, R2 = .06, adjusted R2 = .05, p = .01) | B | β | t | Sig. |

| Lack of control | .04 | .24 | 2.82 | .01** |

| Alcohol (R = .28, R2 = .08, adjusted R2 = .07, p = .00) | B | β | t | Sig. |

| Lack of control | .05 | .28 | 3.49 | .00* |

p < .01.

p < .05.

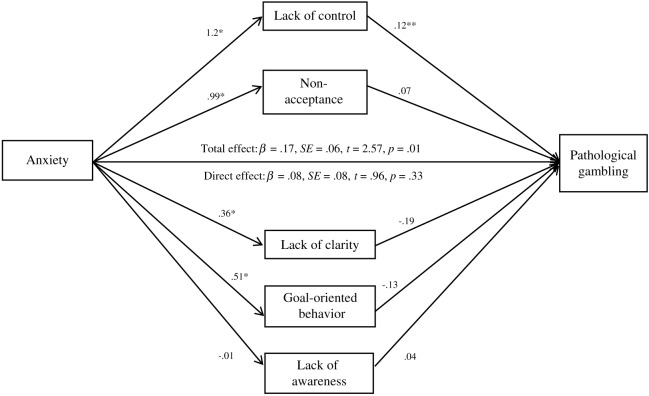

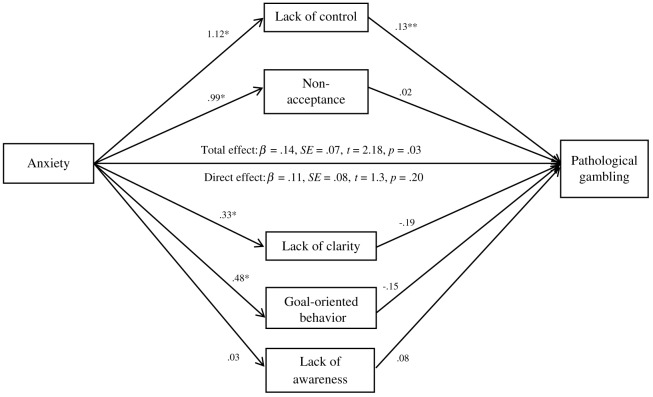

Based on correlational analyses, the mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation between anxiety and pathological gambling was measured through a multiple mediation model, controlling and not controlling for the effect of drug and alcohol. These analyses were not conducted in the case of depression, as it did not correlate with pathological gambling. In both models, a-path, b-path, and c-path were significant, and the c’-path was not significant, showing a full mediation effect of the difficulties in emotion regulation in the relationship between anxiety and pathological gambling, both controlling and not controlling for the effect of drug and alcohol abuse (Figures 1 and 2). The partial effect of control variables on the dependent variable was not significant in either model, meaning that none of the covariates included in both models had a significant effect on the relationship. Additionally, indirect effects were measured by employing 5000 bootstrap samples. A specific indirect effect of lack of control was found in the model controlling for the effect of drug and alcohol abuse [b = .15, 95% BC CI (.02–.31)] and in the model without controlling for drug and alcohol abuse [b = .15, 95% BC CI (.03–.31)].

Figure 1.

Mediational effect of emotion regulation between anxiety and pathological gambling (*p < .001, **p < .05)

Figure 2.

Mediational effect of emotion regulation between anxiety and pathological gambling, controlling for drugs and alcohol (*p < .001, **p < .05)

Discussion

The results showed significant differences between gamblers and non-gamblers in emotion regulation difficulties, anxiety, depression, and drug abuse. In the case of emotion regulation, the results were in accordance with those obtained by Williams, Geisham, Eerskine, and Cassedy (2012) who found that pathological gamblers scored higher on measures of emotion regulation difficulties. However, that study did not find significant differences in non-acceptance, whereas in this study, differences were found in that variable and with a high effect size. The results of this study support those from previous studies showing that individuals with addictions may have greater difficulties with emotion regulation. Previous studies of substance abuse disorders have found similar results, such as the study from Fox, Axelrod, Paliwal, Sleeper, and Sinha (2007), which found higher levels of emotion dysregulation, except for lack of clarity. As mentioned before, pathological gambling may be a way of regulating negative emotions and a consequence of failures in self-control (Tice, Bratslavsky, & Baumeister, 2001). Nevertheless, few studies have measured difficulties of emotion regulation in pathological gamblers (Estévez et al., 2014; Williams, Geisham, Eerskine, & Cassedy, 2012), so this study strengthens the scarce evidence in this field. Pathological gamblers also had more anxiety and depression, consistent with the scientific literature (Parhami, Mojtabai, Rosenthal, Afifi, & Fong, 2014). Moreover, there were significant differences in drug abuse, in accordance with previous studies that documented a co-occurrence of drug use and pathological gambling (Rush, Bassani, Urbanoski, & Castel, 2008). However, unexpectedly, significant differences were not found in alcohol use, despite previous studies that have reported comorbidity of alcohol abuse in gamblers (Griffiths, Wardle, Orford, Sproston, & Erens, 2011; Lorains, Cowlishaw, & Thomas, 2011)). According to previous research, pathological gambling and alcohol abuse are typically not concurrent in treatment-seeking samples (Ladd & Petry, 2003; Stinchfield & Winters, 2001) in spite of their epidemiological association. This finding may apply to the sample of this study, as pathological gamblers were recruited in centers of treatment for pathological gambling. Moreover, pathological gamblers with a high alcohol abuse may have sought treatment in or have been referred to centers of treatment for alcohol abuse. Also, the existence of differences in sociodemographic data such as age, educational level, or marital status may have biased these results. Further studies with more balanced samples and including pathological gamblers from different clinical settings may provide additional data on this result.

Besides, correlation analyses also showed that difficulties of emotion regulation correlated significantly with all of these variables: pathological gambling, alcohol and drug abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology. These results are consistent with the few previous studies available in this regard (Estévez et al., 2014; Veilleux, Skinner, Reese, & Shaver, 2014; Williams, Geisham, Eerskine, & Cassedy, 2012) and remark that difficulties of emotion regulation may be related to pathological gambling and the associated disorders. Regression analyses showed that emotion regulation difficulties predicted pathological gambling, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and anxious and depressive symptomatology in the group of gamblers. This supports previous theories that point to difficulties in emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic factor that may predict numerous psychological disorders (Kring & Sloan, 2009; Trosper, Buzzella, Bennett, & Ehrenreich, 2009). Nevertheless, the specific subscale that was predictive was not the same in each case. One variable that stood out was non-acceptance, which predicted pathological gambling, anxiety, and depression. This subscale measures the tendency of individuals to negatively judge their inner emotional experience, and as a consequence, to react with shame or discomfort to their own emotions. The non-acceptance of emotional experiences is a defining aspect of factors such as experiential avoidance or distress tolerance, which can drive individuals to engage in addictive behaviors to avoid unpleasant inner experiences (Luciano, Páez-Blarrina, & Valdivia-Salas, 2010). Pathological gambling has been associated with experiential avoidance (Riley, 2014), in the same line as other addictions that have also been related to experiential avoidance (Levin, Lillis, Seeley, Hayes, Pistorello, & Biglan, 2012) or lower distress tolerance (Howell, Leyro, Hogan, Buckner, & Zvolensky, 2010; Hsu, Collins, & Marlatt, 2013). Therefore, gambling as a way of avoiding unpleasant emotions may be related to a greater tendency to reject them. Gambling may be used by some gamblers as a coping strategy to regulate unwanted private events (Riley, 2014). In fact, the presence of emotion regulation difficulties may stem from the evaluation of internal experience, rather than actual greater levels of arousal and distress (Tull & Roemer, 2007). Previous research has point to gambling as a way of alleviating depression and anxiety (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002), but this is the first one to find non-acceptance as a common predictor of gambling, anxiety, and depression. Lack of control, for its part, was found to be a predictor of both drug and alcohol abuse in pathological gamblers. These results are also novel and may be in accordance with the pathway model postulated by Blaszczynski and Nower (2002). Pathway model proposes that gamblers with associated substance abuse would form a group of gamblers with an antisocial/impulsive profile characterized by higher impulsivity. The Lack of Control subscale includes items that in the original English version of the DERS were included in the subscale of “Difficulties in the Control of Impulsivity.” These results, therefore, are in accordance with the postulates of the pathway model (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002). These findings could be important in this field, since it is the first study to explore difficulties of emotion regulation as a common predictor of pathological gambling and the associated dysfunctional symptomatology. Future studies may be conducted exploring if the treatment of emotion regulation difficulties could be beneficial for reducing pathological gambling and comorbid disorders.

Finally, we found difficulties in emotion regulation to fully mediate the relationship between anxiety and pathological gambling. These results are similar to those obtained by Weiss, Tull, Viana, Anestis, and Gratz (2012) who also found a full mediation effect in the relationship between post-traumatic stress disorder and drug abuse. This is one of the first studies to point to difficulties of emotion regulation as mediators of the relationship between anxiety and pathological gambling. Previous research has found only a partial mediation effect between pathological gambling and anxiety in adolescents (Estévez et al., 2014). In our study, however, with adult pathological gamblers and controlling for the effects of drug and alcohol abuse and age, a full mediation effect was found. In both cases, lack of control stood out as a mediator variable of that relationship. This subscale measures the feeling of being overwhelmed due to the emotional intensity and persistence of negative emotional states. Therefore, greater difficulties to regulate emotions may result in greater attempts to gamble as a way of managing anxiety. These results are consistent with the literature that postulates that gambling may be a way to regulate emotions and cope with anxiety (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Shead, Callan, & Hodgins, 2008; Stewart & Zack, 2008).

This study has some limitations. First, due to its correlational design, causal relationships cannot be stated, and the relationships found could also be bidirectional. Longitudinal studies would help to determine the directionality of our findings. Additionally, drug and alcohol abuse, and anxiety and depression were measured with screening instruments. The instruments were also self-report measures, which may have biased the results and could have been affected by social desirability in the case of addictions. Moreover, the sample comprised pathological gamblers in treatment. Future replications with samples of gamblers who are not in treatment would be advisable to enhance the generalizability of these results. Another potential limitation is the lack of measures of other disorders, such as borderline personality disorder, which has also been associated with emotion regulation difficulties and addictive behaviors (Axelrod, Perepletchikova, Holtzman, & Sinha, 2011). That factor could have influenced our results; so, it should be included in future studies to measure its effect. Finally, the sample comprised only males. Future studies should also include women because it has been found that women may have a greater tendency to engage in gambling behavior as a form of escape (Zangeneh, Blaszcyznski, & Turner, 2008).

Conclusions

In conclusion, pathological gamblers may present emotion regulation difficulties, which may also constitute a common predictor of pathological gambling and comorbid disorders. Also, difficulties of emotion regulation mediated the relationship between anxious symptomatology and pathological gambling, either when controlling or not controlling for the effect of drug and alcohol abuse. These results are novel in pathological gambling and provide relevant information for clinical practice. The treatment of emotion regulation difficulties, included in approaches such as dialectic-behavioral therapy (Lynch, Chapman, Rosenthal, Kun, & Linehan, 2006) or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (Hayes & Feldman, 2004), might be useful for the common treatment of pathological gambling and other pathological entities associated with it. Authors such as Petry and Champine (2012) have suggested the integration and unification of treatments oriented to treat pathological gambling and other substance and alcohol use disorders, and emotion regulation may be a useful element in that integration. Therefore, the treatment of pathological gambling and comorbid disorders may benefit from an added focus on improving emotion regulation abilities.

Authors’ contribution

PJ contributed to study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, obtained funding. AE contributed to study concept and design, study supervision, analysis and interpretation of data. IU contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, study supervision. All authors had full access to all data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

Funding sources: This research was supported by grants from the University of Deusto “Programa de Ayudas para Formación de Personal Investigador” and Basque Government’s “Programa Predoctoral de Formación de Personal Investigador No Doctor.”

References

- Aldao A., Nolen-Hoeksema S., Schweizer S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod S. R., Perepletchikova F., Holtzman K., Sinha R. (2011). Emotion regulation and substance use frequency in women with substance dependence and borderline personality disorder receiving dialectical behavior therapy. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(1), 37–42. doi:10.3109/00952990.20.10.535582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes G. M., Welte J. W., Tidwell M. C. O., Hoffman J. H. (2015). Gambling and substance use: Co-occurrence among adults in a recent general population study in the United States. International Gambling Studies, 15(1), 55–71. doi:10.1080/14459795.2014.990396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A., Nower L. (2002). A pathways model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction, 97(5), 487–499. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley S. (2000). Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder C. R. (2001). Life stress, physiological and subjective indexes of negative emotionality, and coping reasons for drinking: Is there evidence for a self-medication model of alcohol use? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 15(3), 237–245. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.15.3.237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. L., Frone M. R., Russell M., Mudar P. (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990–1005. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W. M., Klinger E. (1990). Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: A model. In Cox W. M. (Ed.), Why people drink (pp. 291–311). New York, NY: Gardner Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davison M. K., Bershadsky B., Beiber J., Silversmith D., Maruish M. E., Kane R. L. (1997). Development of a brief, multidimensional, self-report instrument for treatment outcomes assessment in psychiatric settings: Preliminary findings. Assessment, 4(3), 259–276. doi:10.1177/107319119700400306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis L. R. (2002). SCL-90-R. Cuestionario de 90 ítems [SCL-90-5. 90 items questionnaire]. Madrid: TEA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Echeburúa E., Báez C., Fernández-Montalvo J., Páez D. (1994). El Cuestionario de Juego de South Oaks (SOGS): Validación española [South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): Spanish validation]. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 20, 769–791. [Google Scholar]

- el-Guebaly N., Patten S. B., Currie S., Williams J. A., Beck C. A., Maxwell C. J., Jian Li W. (2006). Epidemiological associations between gambling behavior, substance use and mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Gambling Studies, 22(3), 275–287. doi:10.1007/s10899-006-9016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. C., Axelrod S. R., Paliwal P., Sleeper J., Sinha R. (2007). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2), 298–301. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox H. C., Hong K. A., Sinha R. R. (2008). Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 33(2), 388–394. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz K. L., Roemer L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54. doi:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94 [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M., Wardle H., Orford J., Sproston K., Erens B. (2011). Internet gambling, health, smoking and alcohol use: Findings from the 2007 British Gambling Prevalence Survey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(1), 1–11. doi:10.1007/s11469-009-9246-9 [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2013). Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. M., Feldman G. (2004). Clarifying the construct of mindfulness in the context of emotion regulation and the process of change in therapy. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 255–262. doi:10.1093/clipsy.bph080 [Google Scholar]

- Estévez A., Herrero-Fernández D., Sarabia I., Jauregui P. (2014). El papel mediador de la regulación emocional entre el juego patológico, uso abusivo de Internet y videojuegos y la sintomatología disfuncional en jóvenes y adolescentes [Mediating role of emotional regulation between impulsive behavior in gambling, Internet and videogame abuse, and dysfunctional symptomatology in young adults and adolescents]. Adicciones, 26(4), 282–290. doi:10.20882/adicciones.26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervás G., Jódar R. (2008). Adaptación al castellano de la Escala de Dificultades en la Regulación Emocional [Adaptation into Spanish of the Difficulties of Emotion Regulation Scale]. Clínica y Salud, 19(2), 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann S. G., Sawyer A. T., Fang A., Asnaani A. (2012). Emotion dysregulation model of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 29(5), 409–416. doi:10.1002/da.21888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A. N., Leyro T. M., Hogan J., Buckner J. D., Zvolensky M. J. (2010). Anxiety sensitivity, distress tolerance, and discomfort intolerance in relation to coping and conformity motives for alcohol use and alcohol use problems among young adult drinkers. Addictive Behaviors, 35(12), 1144–1147. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. H., Collins S. E., Marlatt G. A. (2013). Examining psychometric properties of distress tolerance and its moderation of mindfulness-based relapse prevention effects on alcohol and other drug use outcomes. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1852–1858. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R., Jessor S. L. (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York, NY: Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian E. J. (1985). The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142(11), 1259–1264. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kober H., Bolling D. (2014). Emotion regulation in substance use disorders. In Gross J. J. (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed.) (pp. 428–446). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kring A. M., Sloan D. M. (2009). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd G. T., Petry N. M. (2003). A comparison of pathological gamblers with and without substance abuse treatment histories. Experimentaland Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11(3), 202–209. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. R., Blume S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9), 1184–1188. doi:10.1176/ajp.144.9.1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin M. E., Lillis J., Seeley J., Hayes S. C., Pistorello J., Biglan A. (2012). Exploring the relationship between experiential avoidance, alcohol use disorders, and alcohol-related problems among first-year college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(6), 443–448. doi:10.1080/07448481.2012.673522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorains F. K., Cowlishaw S., Thomas S. A. (2011). Prevalence of comorbid disorders in problem and pathological gambling: Systematic review and meta‐analysis of population surveys. Addiction, 106(3), 490–498. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciano C., Páez-Blarrina M., Valdivia-Salas S. (2010). La Terapia de Aceptación y compromiso (ACT) en el consumo de sustancias como estrategia de Evitación Experiencial. [Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in substance consumption as a strategy of Experiential Avoidance]. International Journal of Clinical Health & Psychology, 10(1), 141–165. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T. R., Chapman A. L., Rosenthal M. Z., Kuo J. R., Linehan M. M. (2006). Mechanisms of change in dialectical behavior therapy: Theoretical and empirical observations. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(4), 459–480. doi:10.1002/jclp.20243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T. L., Walsh K. L., DiLillo D. (2010). Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(12), 967–976. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parhami I., Mojtabai R., Rosenthal R. J., Afifi T. O., Fong T. W. (2014). Gambling and the onset of comorbid mental disorders: A longitudinal study evaluating severity and specific symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 20(3), 207–219. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000450320.98988.7c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrero Pérez E. J., Rodríguez Monje M. T., Gallardo Alonso F., Fernández Girón M., Pérez López M., Chicharro Romero J. (2007). Validación de un instrumento para la detección de trastornos del control de impulsos y adicciones: el MULTICAGE CAD-4[Validation of a tool for screening of impulse control disorders and addiction: The MULTICAGE CAD-4]. Trastornos Adictivos, 9(4), 269–278. doi:10.1016/S1575-0973(07)75656-8 [Google Scholar]

- Petry N. M. (2007). Gambling and substance use disorders: Current status and future directions. American Journal on Addictions, 16(1), 1–9. doi:10.1080/10550490601077668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N. M., Champine R. (2012). Drug abuse and addiction in medical illness. In Verster J. , Brady K. , Galanter M. , Conrod P. (Eds.), Gambling and Drug Abuse (pp. 489–496). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Hayes A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley B. (2014). Experiential avoidance mediates the association between thought suppression and mindfulness with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30(1), 163–171. doi:10.1007/s10899-012-9342-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J., Sareen J., Cox B. J., Bolton J. (2009). Self-medication of anxiety disorders with alcohol and drugs: Results from a nationally representative sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1), 38–45. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush B. R., Bassani D. G., Urbanoski K. A., Castel S. (2008). Influence of co‐occurring mental and substance use disorders on the prevalence of problem gambling in Canada. Addiction, 103(11), 1847–1856. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandín B., Valiente R. M., Chorot P., Santed M. A., Lostao L. (2008). SA-45: Forma abreviada del SCL-90 [SA-45: Short form of SCL-90]. Psicothema, 20(2), 290–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L. N., Grant J. E., Odlaug B. L. (2012). Emotion regulation and impulsivity in young adults. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(5), 651–658. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shead N., Callan M. J., Hodgins D. C. (2008). Probability discounting among gamblers: Differences across problem gambling severity and affect-regulation expectancies. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(6), 536–541. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.008. [Google Scholar]

- Silk J. S., Steinberg L., Morris A. S. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74(6), 1869–1880. doi:10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J. S., Gaher R. M., Correia C. J., Hansen C. I., Christopher M. S. (2005). An affective–motivational model of marijuana and alcohol problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(3), 326–334. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S. H., Zack M. (2008). Development and psychometric evaluation of a three‐dimensional Gambling Motives Questionnaire. Addiction, 103(7), 1110–1117. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02235.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S. H., Zack M., Collins P., Klein R. M. (2008). Subtyping pathological gamblers on the basis of affective motivations for gambling: Relations to gambling problems, drinking problems, and affective motivations for drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(2), 257–268. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R., Winters K. C. (2001). Outcome of Minnesota’s gambling treatment programs. Journal of Gambling Studies, 17(3), 217–245. doi:10.1023/A:1012268322509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice D. M., Bratslavsky E., Baumeister R. F. (2001). Emotional distress regulation takes precedence over impulse control: If you feel bad, do it! Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 53–67. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trosper S. E., Buzzella B. A., Bennett S. M., Ehrenreich J. T. (2009). Emotion regulation in youth with emotional disorders: Implications for a united treatment approach. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(3), 234–254. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0043-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull M. T., Roemer L. (2007). Emotion regulation difficulties associated with the experience of uncued panic attacks: Evidence of experiential avoidance, emotional nonacceptance, and decreased emotional clarity. Behavior Therapy, 38(4), 378–391. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux J. C., Skinner K. D., Reese E. D., Shaver J. A. (2014). Negative affect intensity influences drinking to cope through facets of emotion dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 59, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wareham J. D., Potenza M. N. (2010). Pathological gambling and substance use disorders. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 242–247. doi:10.3109/00952991003721118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N. H., Tull M. T., Anestis M. D., Gratz K. L. (2013). The relative and unique contributions of emotion dysregulation and impulsivity to posttraumatic stress disorder among substance dependent inpatients. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 128(1), 45–51. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss N. H., Tull M. T., Viana A. G., Anestis M. D., Gratz K. L. (2012). Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3), 453–458. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside U., Chen E., Neighbors C., Hunter D., Lo T., Larimer M. (2007). Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors, 8(2), 162–169. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A. D., Grisham J. R., Erskine A., Cassedy E. (2012). Deficits in emotion regulation associated with pathological gambling. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(2), 223–238. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8260.2011.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangeneh M., Blaszczynski A., Turner N. E. (2008). In the pursuit of winning. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]