Abstract

Introduction:

This study provides the first overview of the perceived general and mental health, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and level of disability, as well as factors associated with disability severity, among Canadian adults with mood and/or anxiety disorders, using a population-based household sample.

Methods:

We used data from the 2014 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada– Mood and Anxiety Disorders Component. The sample consists of Canadians aged 18 years and older with self-reported mood and/or anxiety disorders from the 10 provinces (n = 3361; response rate 68.9%). We conducted descriptive and multinomial multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Results:

Among Canadian adults with mood and/or anxiety disorders, over one-quarter reported “fair/poor” general (25.3%) and mental (26.1%) health; more than one-third (36.4%) reported one or more activity limitations; half (50.3%) stated a job modification was required to continue working; and more than one-third (36.5%) had severe disability. Those with concurrent mood and anxiety disorders reported poorer outcomes: 56.4% had one or more activity limitations; 65.8% required a job modification and 49.6% were severely disabled. Upon adjusting for individual characteristics, those with mood and/or anxiety disorders who were older, who had a household income in the lowest or lower-middle adequacy quintile or who had concurrent disorders were more likely to have severe disability.

Conclusion:

Findings from this study affirm that mood and/or anxiety disorders, especially concurrent disorders, are associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes. Results support the role of public health policy and programs aimed at improving the lives of people living with these disorders, in particular those with concurrent disorders.

Keywords: mood disorders, anxiety disorders, health status, activity limitations, work restrictions, disability, health utilities index, health survey, population-based survey

Highlights

Canadian adults with mood and/or anxiety disorders were more likely to report having “fair/poor” general and mental health and more likely to have severe disability compared to the general population.

Those with concurrent mood and anxiety disorders were more likely to report having “fair/poor” perceived general and mental health, more activity limitations and work-related restrictions and severe disability compared to those with one type of disorder.

The majority of those with concurrent disorders required a job modification to continue working, and nearly half had to stop work altogether because of their disorders.

Severe disability was the most prevalent disability category among those with concurrent disorders.

Adjusting for individual characteristics, those with mood and/or anxiety disorders who were older, who had a household income in the lowest or lower-middle adequacy quintile and/or who had concurrent disorders were more likely to have severe disability.

Introduction

Mood and anxiety disorders can have a significant impact on physical and mental health, level of disability and overall quality of life.1,2 These disorders are also associated with significant economic costs relating to the use of medical resources and to productivity losses.3 Mood disorders include depressive and bipolar disorders, and anxiety disorders encompass a variety of conditions among which generalized anxiety disorder is the most common. In 2012, an estimated 3.5 million (12.6%) Canadians aged 15 years and older reported having symptoms consistent with a mood disorder, and 2.4 million (8.7%) reported having symptoms consistent with generalized anxiety disorder at some point during their life.4,* Given their high prevalence and wide-ranging impacts, mood and anxiety disorders are a major public health challenge in Canada.

Globally, unipolar depression and anxiety disorders were ranked first and sixth, respectively, as main contributors to years of life lost to disability in the 2012 Global Burden of Disease Study.5 In Canada, approximately 4 million person-years were lost to disability overall, of which 12% were attributed to unipolar depression and bipolar disorder and about 3% to anxiety disorders. Furthermore, the Canadian Survey on Disability estimated that in 2012, 3.8 million (13.7%) Canadians aged 15 years and older had some type of disability; 1.1 million (3.9%) reported having a disability related to mental health for which depression, bipolar and anxiety disorders were the most commonly reported underlying conditions.6

Disability is a complex, multi-dimensional concept. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities defines people with disabilities as “those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”7

Many studies have used measures of activities of daily living (ADLs)† and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs)‡ to define disability based on necessary functional activities that permit a person to lead an independent life.8-10 These measures are usually derived from self-reported data collected in health surveys. The sets of activities assessed vary across surveys; therefore, it is difficult to compare results between different studies. However, studies that have used these measures have reported strong associations between depression and activity limitations.8,9,11 An alternate measure of disability is the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI).12,13 The disability categories based on this instrument allow for the systematic measurement and comparison of disability levels between populations.

A large body of research has shown a consistent association between depression and limitations in ADLs, IADLs and disability.8-10,14 Furthermore, mood and anxiety disorders have been found to be associated with a loss in work productivity. 15-17 However, to our knowledge, only a few Canadian studies have examined the association between depression and activity limitations14 and none have examined the association between mood and/or anxiety disorders, work-related restrictions and level of disability. Therefore, there is a need to obtain information regarding these relationships at a population level in Canada to inform policy and practice initiatives, facilitate the development of interventions that could diminish disability related to mood and anxiety disorders and assist in monitoring potential improvements over time.

Using data from a population-based household sample of Canadian adults living with mood and/or anxiety disorders, we had the following objectives: (1) describe the general and mental health status, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and disability; and (2) identify the sociodemographic characteristics associated with severe levels of disability.

Methods

Data source and study sample

We used data from the 2014 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada– Mood and Anxiety Disorders Component (SLCDC-MA). The 2014 SLCDC-MA surveyed Canadians aged 18 years and older living in private dwellings in the 10 provinces identified through the 2013 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) – Annual Component as having responded “yes” to having received a mood and/or anxiety disorder diagnosis from a health professional that had lasted or was expected to last 6 months or more. The final sample included 3361 respondents (68.9% response rate) with 508 from the Atlantic region, 593 from Quebec, 1162 from Ontario, 690 from the Prairie region and 408 from British Columbia. The methodology of the 2014 SLCDC-MA and the sociodemographic characteristics of the final sample have been described elsewhere.18 The term “mood and/or anxiety disorders” used throughout this article refers to those who have self-reported, professionally diagnosed mood disorders only, anxiety disorders only or concurrent mood and anxiety disorders.

Measures

Health status was assessed using the indicators of perceived general health and mental health. Both were measured by asking respondents, “In general, would you say your health [or mental health] is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?”19

Activity limitations were measured by asking respondents how much (“a lot,” “a little,” or “not at all”) in the past 12 months had their mood and/or anxiety disorders limited them in seven activities: recreation/leisure/hobbies; exercise/playing sports; social activities with family/ friends; doing household chores; running errands or shopping; travelling/taking vacations; and bathing or dressing. These questions were based on the Health Status (SF-36) module in the 2013 CCHS–Annual Component and designed to capture activity limitations attributable to mood and/or anxiety disorders.19

Work-related restrictions were evaluated by asking respondents if they, in their current or past work environments, ever required a job modification including changing the number of hours (“yes” or “no”); the type of work (“yes” or “no”) and/or the way in which they carried out their tasks at work (“yes” or “no”); or whether they had ever stopped working (“yes” or “no”) altogether because of their mood and/or anxiety disorders. These questions were based on the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and designed to capture work-related restrictions attributable to mood and/or anxiety disorders.20

Level of disability was based on the HUI, which describes functional health based on eight domains: vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, cognition and pain.21 Each domain has five to six levels of functioning ranging from the lowest level to full capacity. The scores for each domain are combined into a single global utility score that ranges from 1 (perfect health) through 0 (death) to −0.36 (a state worse than death). HUI values in the negative range reflect health states in which death might be preferable. HUI disability categories were proposed by Feeny and Furlong,12,13 and validated by Feng et al.22 using Canadian data. Four disability categories (“no disability,” “mild disability,” “moderate disability,” and “severe disability”) were defined based on global utilities scores. Participants were considered to have “no disability” if all domains were scored at their highest functional level (HUI = 1); “mild disability” if at least one domain was scored at a reduced level of functioning that can be corrected and does not prevent any activities (0.89 ≤ HUI ≤ 0.99); “moderate disability” if at least one domain was scored at a reduced level of functioning that cannot be corrected and prevents some activities (0.70 ≤ HUI ≤ 0.88); and “severe disability” if at least one domain was scored at a reduced level of functioning that cannot be corrected and prevents many activities (HUI < 0.70).

Statistical analysis

To describe respondents’ health status, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and level of disability by sociodemographic characteristics, we performed a descriptive cross-tabulation analysis. We stratified data by disorder type, i.e. mood disorder only, anxiety disorder only, and concurrent disorders. The sociodemographic characteristics included sex (women, men); age groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–64 and 65+ years); marital status (single/ never married, widowed/divorced/separated, married/living common-law); respondent’s level of education (less than secondary school graduation, secondary school graduation, some post-secondary, post-secondary graduation); adjusted household income adequacy quintiles; Canadian regions (Atlantic region, Quebec, Ontario, Prairie region, British Columbia); area of residence (urban, rural); Aboriginal status (yes, no); and immigrant status (yes, no). We divided respondents into adjusted household income adequacy quintiles based on Statistics Canada’s household income distribution in deciles, i.e. adjusted ratio of respondents’ total household income to the low-income cut-off corresponding to their household and community size.23 We used chi-square tests to determine whether there was an association between the respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and level of disability. A p-value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

To examine the association between level of disability and respondent characteristics, we conducted a multinomial multivariate logistic regression analysis. We adjusted the model for all sociodemographic characteristics and disorder types. Results from the goodness-of-fit tests demonstrated that the model was significant and fit the data well. The likelihood ratio score and Wald tests confirmed that the model with the selected covariates was superior to the model with the intercept only. Odds ratios (ORs) with a p-value less than .05 were deemed statistically significant.

To account for sample allocation and survey design, and to generalize for the total Canadian adult population with mood and/or anxiety disorders, all estimates were weighted§ to represent the study population and the bootstrap methodology was used for variance estimation.24 Only results with a coefficient of variation (CV) less than 33.3% are reported as per Statistics Canada guidelines.25 We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Health status, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and level of disability by disorder type

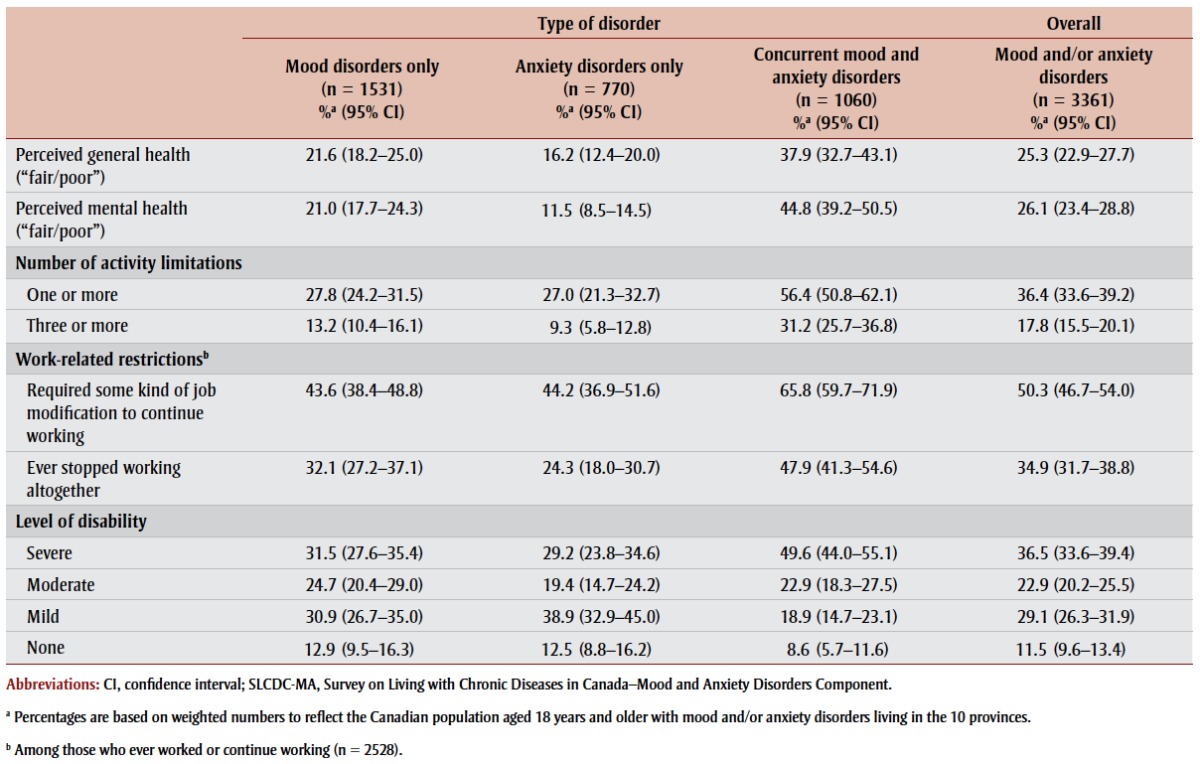

Overall, one in four Canadians aged 18 years and older with self-reported, professionally diagnosed mood and/or anxiety disorders reported “fair/poor” general and mental health (25.3% and 26.1%, respectively) (Table 1). These results varied by type of disorder. Those with concurrent disorders demonstrated poorer health outcomes: 37.9% reported “fair/poor”general health and 44.8% reported “fair/poor” mental health.

TABLE 1. Health status, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and level of disability among Canadians aged 18 years and older with mood and/or anxiety disorders, stratified by type of disorder (n = 3361), 2014 SLCDC-MA.

|

Of those with one type of disorder (i.e. either mood disorders only or anxiety disorders only), fewer than 30% reported that they had “a lot” of limitations in at least one of the seven previously described activity categories, and between 9% and 13% reported they had “a lot” of limitations in at least three of these activities. Among those with concurrent disorders (i.e. co-occurring mood and anxiety disorders), more than half (56.4%) reported limitations in at least one activity and one-third (31.2%) had limitations in at least three. Regardless of the type of disorder, “recreation, leisure or hobbies” and “social activities with family and friends” were among the top three activities for which people reported “a lot” of limitations. The third activity among the top three varied by type of disorder.

In terms of work-related restrictions, half (50.3%) of those with mood and/or anxiety disorders who ever worked or were currently working required some kind of job modification to continue working. More than one-third (34.9%) stopped working altogether because of their disorder(s). The greatest impact on work was observed among those with concurrent disorders, where two-thirds (65.8%) required a job modification to continue working and close to half (47.9%) reported that they had to stop working because of their disorders.

Overall, people with mood and/or anxiety disorders had severe disability more often than other levels of disability (36.5%). Less than one-third of those with only one type of disorder and about half (49.6%) of those with concurrent disorders had severe disability. Only one in 10 people (11.5%) with mood and/or anxiety disorders had no disability.

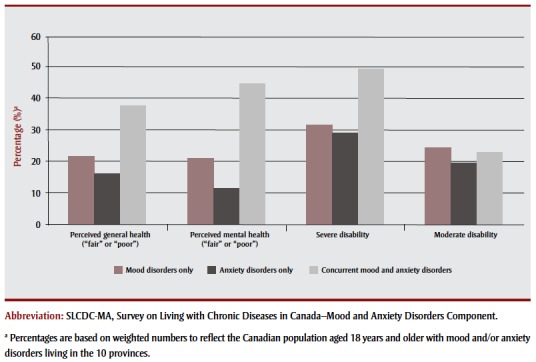

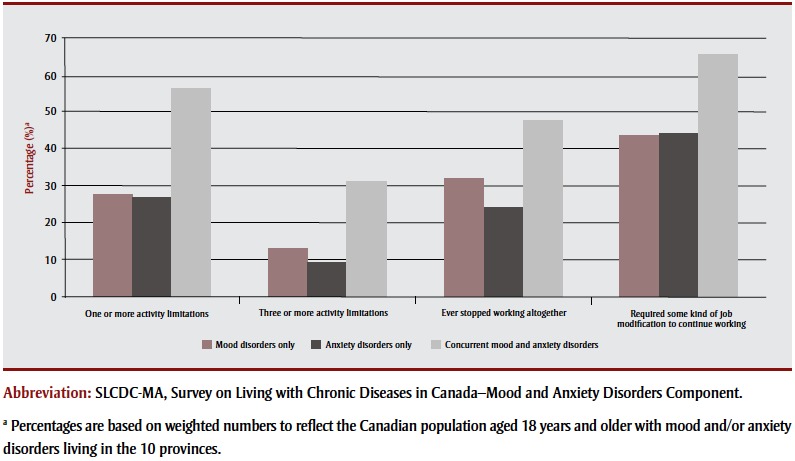

In summary, those with concurrent disorders were more likely to report “fair/poor” general and mental health and a greater number of activity limitations and workrelated restrictions, and more likely to have severe disability compared to those with one type of disorder (Figures 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1. Health status and disability, by type of disorder among Canadians aged 18 and older with mood/or anxiety disorders (n = 3361), 2014 SLCDC-MA.

FIGURE 2. Activity limitations (n = 3361) and work-related restrictions (n = 2528) by type of disorder among Canadians aged 18 years and older with mood and/or anxiety disorders, 2014 SLCDC-MA.

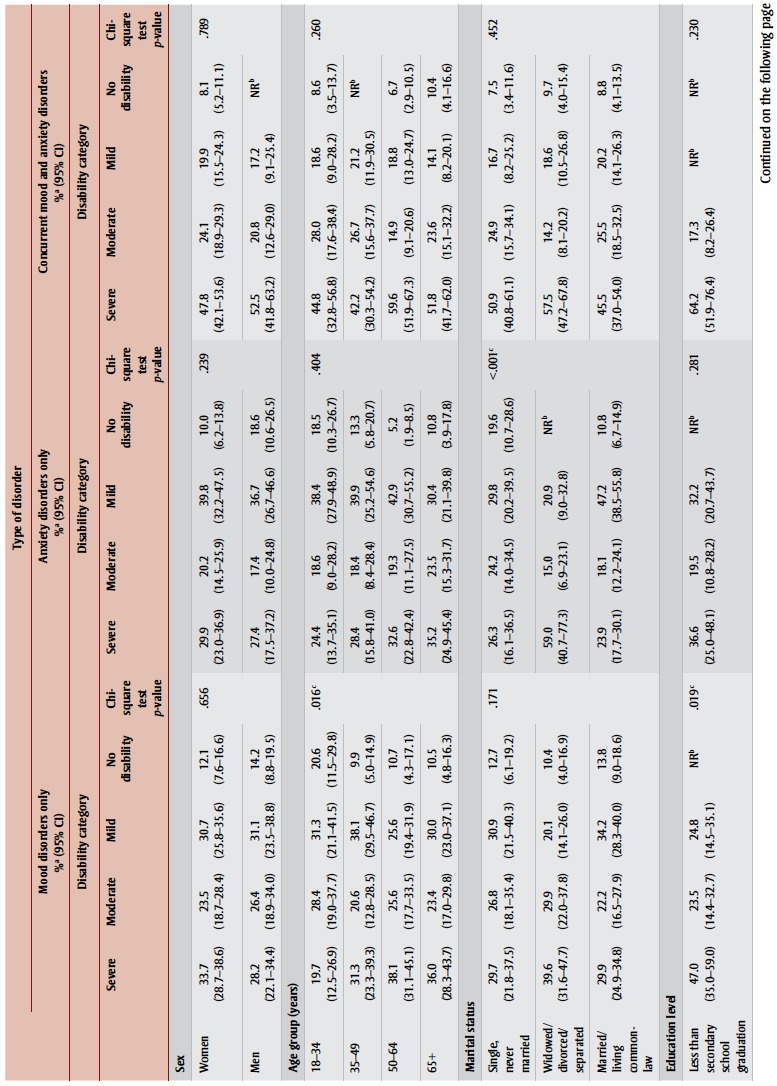

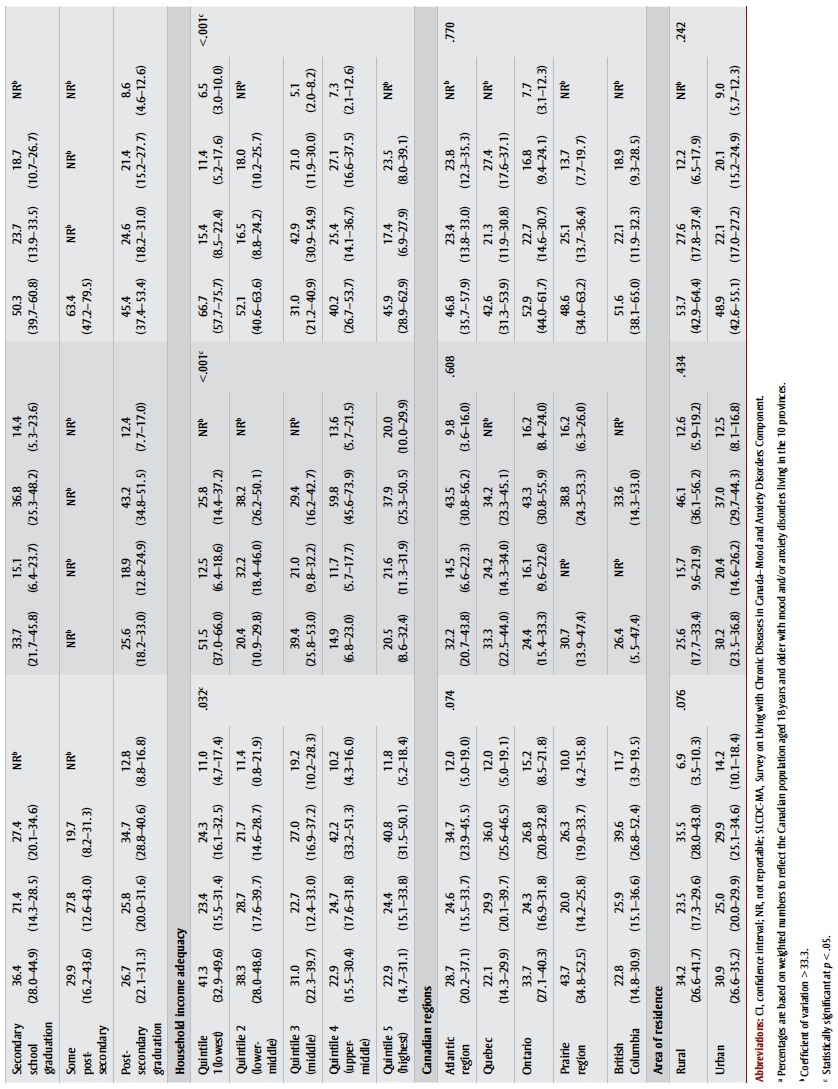

Sociodemographic characteristics by disorder type and level of disability* *

Among those with mood disorders only, significant relationships were found between level of disability and age, level of education, and household income adequacy (Table 2). Those aged 50 years and older were more likely to have severe disability compared to those in the youngest age group. Also, those with less than secondary school education and those in the lowest household income adequacy quintile were more likely to have severe disability compared to those with a post-secondary education and those in the two highest household income adequacy quintiles.

TABLE 2. Sociodemographic characteristics among Canadians aged 18 years and older with mood and/or anxiety disorders, stratified by type of disorder and level of disability (n = 3361), 2014 SLCDC-MA.

|

For those with anxiety disorders only, we found significant relationships between the level of disability and marital status, and level of disability and household income adequacy. Those who were widowed/ divorced/separated were more likely to have severe disability compared to those who were single/never married or married/living common-law. In addition, those in the lowest household income adequacy quintile were more likely to have severe disability than those in the two highest household income adequacy quintiles.

Among those with concurrent disorders, we found a significant relationship between level of disability and household income adequacy only; those in the lowest household income adequacy quintile were more likely to have severe disability than those in the three highest household income adequacy quintiles.

We found no significant relationships between levels of disability and sex, geographical region or area of residence. Due to small sample sizes, a cross-tabulation analysis for immigrant and Aboriginal populations was not possible.

In summary, we observed a higher proportion of those with severe disability to be in the lowest household income adequacy quintile (mood and/or anxiety disorders); to be 50 years of age and older or have less than secondary school level of education (mood disorders only); or to be widowed, divorced or separated (anxiety disorders only).

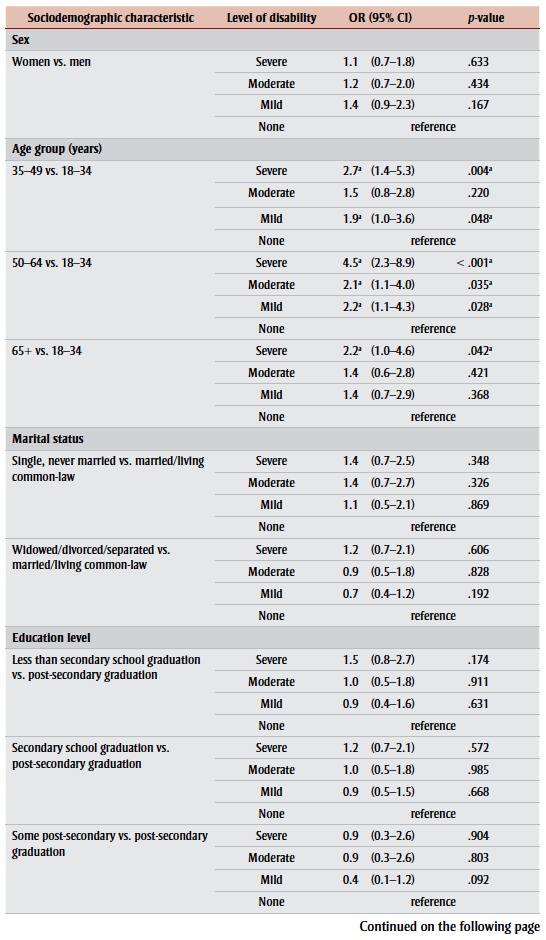

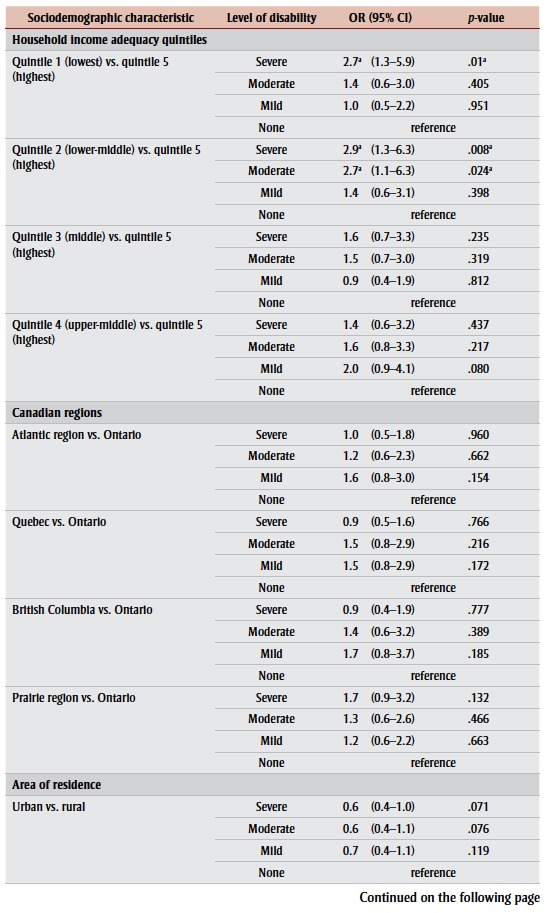

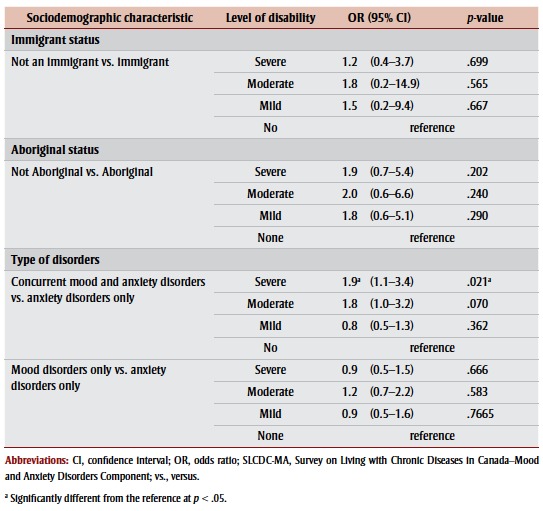

Factors associated with varying levels of disability

Upon adjusting for all sociodemographic characteristics and types of disorder, the results from the multinomial multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that those aged 50 to 64 years were 4.5 times more likely to have severe disability compared to those 18 to 34 years of age (Table 3). To a lesser extent, those aged 35 to 49 and 65 years and older were also more likely to have severe disability compared to the youngest age group (OR = 2.7 and 2.2, respectively). In addition, those in the lowest and lower-middle household income adequacy quintiles were more likely to fall into the severe disability category compared to those in the highest household income adequacy quintile (OR = 2.7 and 2.9, respectively). Lastly, those with concurrent disorders were 1.9 times more likely to be severely disabled compared to those with anxiety disorders only.

TABLE 3. Adjusted odds ratio of falling into “severe,” “moderate” or “mild” disability categories compared to “no disability,” by sociodemographic characteristics and type of disorder among Canadians aged 18 years and older with mood and/or anxiety disorders (n = 3361), 2014 SLCDC-MA.

|

There were no significant ORs found between the individuals’ level of disability and sex, marital status, level of education, immigrant status, Aboriginal status, area of residence or geographical region, with the exception of the Canadian Prairies. When compared to their counterparts living in Ontario, those with mood and/or anxiety disorders in the Prairies were 1.7 times more likely to have severe disability; however, the OR was only marginally statistically significant.

In summary, those at highest risk for severe disability were older in age, especially those between 50 and 64 years, were in the lowest and lower middle household income adequacy quintiles, and had concurrent disorders.

Discussion

The results of our study affirm that mood and anxiety disorders play a significant role in an individual’s perceived general and mental health status. Compared to the general Canadian population surveyed in the 2013 CCHS–Annual Component (i.e. the source survey for the 2014 SLCDC-MA), a significantly greater proportion (2–4 times) of the population affected by mood and/or anxiety disorders reported “fair/poor” general and mental health (data not shown). Similarly, the level of disability found among those with mood and/or anxiety disorders in this study was substantially higher than that found in the general Canadian population. People with mood and/or anxiety disorders had “severe” disability more often than other levels of disability, while the general Canadian household population were more likely to have “mild” disability.22 Furthermore, the findings from this study are consistent with results from previous research indicating that mood and anxiety disorders are associated with substantial limitations in activities8,9,14 and disability.10,26-28

The causal association between mood and anxiety disorders and activity limitations and disability is complex and likely bidirectional. Chronic disease, functional limitations and disability can lead to mood fluctuations, depression8,26 and anxiety.29 On the other hand, longitudinal and cohort studies have demonstrated that mood disorders lead to impairments in a range of activities, even when controlling for potential confounders.14 This relationship may be due to the core symptoms of mood disorders, which include feelings of hopelessness, loss of interest and motivation, indecisiveness, sleep disturbances and difficulty concentrating. Similarly, anxiety disorders may impair activity due to intrusive and uncontrollable worries or fears that interfere with the ability to undertake tasks and the ability to leave the house. Our study demonstrated that mood and/or anxiety disorders are positively associated with an increase in the number of activity limitations and level of disability.

Mood disorders and concurrent mood and anxiety disorders were associated with particularly high rates of moderate to severe disability. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies that show coexisting mood and anxiety disorders increase the level of disability of those affected and have been found to increase resource consumption and health care costs to a greater degree than having either of the conditions alone.30,31 Since epidemiological studies have found both mood and anxiety disorders to be prevalent with high rates of comorbidity,32-35 we anticipate that comorbid mood and anxiety disorders result in substantial disability at the population level.

A similar distribution of disability was observed among men and women, despite the fact that the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders is generally higher among women than men.36 There is no consensus in the literature about the sex pattern in terms of the association between disability and mood and anxiety disorders, or between disability and mental disorders overall. While some studies suggest that women with depression are more likely to have a social and physical disability than their male counterparts,27 others provide evidence of the opposite pattern.8,10,14 The differences across studies may be due to differences in the way they define disability and in the composition of the study populations.

We found that age was associated with level of disability, that is, those who were older, especially those aged 50 to 64 years, had higher levels of disability compared to the youngest age group. These results are in concordance with age-related findings about the use of health services for mood and anxiety disorders37 and may relate to the specific challenges this subpopulation faces, including the higher rates of concurrent physical conditions and conditions related to mental health.7 It has previously been found that people with combined physical and mental conditions have increased odds of disability after controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, occupation and region.38

In addition, a study that explored the association between work stress and mental disorders found that working-age people who reported an imbalance between work and personal and/or family life were at greatest risk for mental disorders, regardless of gender.39 People who must fill multiple roles, such as working and caring for aging parents or in-laws and children at the same time, tend to be between the ages of 45 and 65.40 These individuals, known as the “sandwich generation,” are expected to grow in number as people delay childbearing and as the government advocates for a shift from formal to informal caregiving for older adults.41

When the data were stratified by socioeconomic status, the household income adequacy and level of education were negatively associated with the level of disability among those with mood and/or anxiety disorders. Those with the lowest household income adequacy and an education graduation had higher levels of disability than people with higher household income adequacy and level of education. The association between disability levels and education, however, may be confounded by household income as the OR of falling into severe, moderate or mild disability categories compared to the no disability category for those with less than post-secondary education was not statistically significant when adjusted for other factors including household income adequacy. In general, the results related to socioeconomic status from this study are consistent with other research that has found lower income and level of education to be associated with negative health outcomes.42,43

Another important finding from this study is the profound impact of mood and/or anxiety disorders on work function, especially among those with concurrent disorders. Mood and anxiety disorders vary in regard to their duration and severity; therefore, individuals with recurrent or chronic symptoms and those who have more severe symptoms might be particularly prone to work disability. While the survey data did not permit an examination of workplace absenteeism and presenteeism, the literature suggests that people with depressive and anxiety disorders have an elevated risk of work absence and impaired work performance.44-46 Furthermore, it has been estimated that about 500 000 Canadians are absent from their workplace every day because of depression.47 It was not possible to consider the potential impact of underemployment (i.e. people with qualifications that would allow them to attain better career opportunities had it not been for their mental illness), as this information was not collected in the 2014 SLCDC-MA.

The high rates of work-related restrictions and disability found among those with mood and/or anxiety disorders in this study underscore the importance of initiatives such as the 2013 National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety.48 The Standard, championed by the Mental Health Commission of Canada, is a voluntary set of guidelines, tools and resources for promoting employees’ overall psychological health and preventing psychological harm due to workplace factors. It applies to everyone, regardless of their mental health status. The Standard supports Canada’s mental health priorities as outlined in Changing Directions, Changing Lives: The Mental Health Strategy for Canada,49 which recommends the wide adoption of psychological health and safety standards in Canadian workplaces.50

Strengths and limitations

One of the many strengths of this study is that we were able to stratify the analyses by type of disorder, permitting a comparison of the separate and combined impact of mood and anxiety disorders on health status, activity limitations, work-related restrictions and level of disability. A second strength of this study is its use of the HUI to define disability categories. The HUI is one of the leading instruments in the measurement of functional health, and the disability categories that are based on HUI have been validated for the assessment of disability and health-related quality of life.22 It allows for the systematic measurement and comparison of disability between populations with specific characteristics.

Nevertheless, the results should be interpreted in light of several limitations. For instance, the identification of people with mood or anxiety disorders and their health activity, work-related and disability status were dependent on self-disclosure, with no third-party corroboration or verification. While this is the most practical method of assessing these health-related issues in a large population, self-report is susceptible to error due to social-desirability bias, recall bias and/or conscious nonreporting, resulting in potential under- or overestimation of disorder burden both individual and societal. Furthermore, since individuals affected by mood and/or anxiety disorders (particularly those with severe symptoms) may be less inclined to participate in such a survey, the estimates within are likely conservative.51

Of the respondents selected for the 2014 SLCDC-MA, 17% were deemed to be outof- scope for any one of the following reasons: being incorrectly classified as having the condition in the 2013 CCHS, deliberately providing answers to be screened out of the survey, having emigrated or having died. Because the data were not adjusted for these out-of-scope cases, a comparison of the health outcomes between the adult population without mood and anxiety disorders based on the 2013 CCHS and the adult population with mood and/or anxiety disorders based on the 2014 SLCDC-MA was not performed in this study. While the findings from this study suggest that mood and anxiety disorders have a substantial impact on the health and well-being of those affected, we could not evaluate the difference between these two populations.

Another limitation of the study relates to the generalizability of the findings to the entire Canadian population. Individuals living in the three territories, and some populations known to be at risk for mental illness such as Aboriginal people living on reserves or Crown lands,52,53 the homeless,54 institutionalized residents55,56 and full-time members of the Canadian Forces57 were not included. For instance, it is well known that the prevalence of major depression among Canadian seniors living in long-term care facilities is higher (3–4 times) than those living in private dwellings,55,58 and that the level of disability among those living in correctional facilities is much higher than those living in the community.56,59 In light of this, the results of this study likely underestimate the impacts of mood and anxiety disorders on affected Canadians.

Conclusion

This is the first population-based Canadian study that provides a comprehensive overview of the general and mental health status, usual and work-related activities and level of disability among those with mood and/or anxiety disorders.

Findings highlight the importance of early detection of symptoms and timely access to treatment in mitigating the negative impact of these disorders on people’s health and ultimately, improving their well-being and participation in the workplace and day-to-day life. In addition, results will help to inform policies and programs that aim to promote positive mental health and well-being in the workplace, including workplace accommodations. Keeping those at highest risk for severe disability in the workplace longer may help mitigate some of the issues that challenge older adults’ mental health (e.g. financial stress, social isolation).

The significant levels of disability associated with mood and/or anxiety disorders also point to the importance of tailoring treatment efforts to address activity and work limitations rather than focus too narrowly on symptom reduction. Furthermore, results emphasize the importance of promoting Canadians’ mental health throughout the life course and in various life settings (i.e. school, workplace, community, senior residence, etc.) through anti-stigma strategies, public awareness, education and training.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Financial and material support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Authors’ contributions

L. Loukine contributed to the paper concept, conducted statistical analysis and contributed to the manuscript writing. S. O’Donnell and E. Goldner contributed to the manuscript writing and revisions. L. McRae and H. Allen critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Prevalence rates were based on a modified World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO-CIDI), which is a standardized instrument for assessment of mental disorders and conditions according to an operationalization of the definitions and criteria of the DSM-IV. Prevalence estimates based on WHO-CIDI may be incomparable to the self-reported prevalence of professionally diagnosed mood and anxiety disorders.

ADLs include basic self-care tasks, e.g. “the things we normally do in our day-to-day life such as feeding ourselves, bathing, dressing, grooming, work, homemaking, and leisure” (MedTerms Medical Dictionary. [cited 2015 Aug 28]. Available from http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=2131)

IADLs include complex life skills required to live independently successfully and consist of domains such as housework, taking medications, managing money, shopping for groceries or clothing and using communication devices and transportation. (Bookman A, Harrington M, Pass L, Reisner E. The family caregiver handbook: finding elder care resources in Massachusetts. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 2007.)

Sample weights adjusted by Statistics Canada for exclusions, sample selection, in-scope rates, non-response and permission to link and share.

Due to small sample size, some estimates had a high CV (> 33.3%), indicating high sampling variability and estimates of unacceptable quality.

References

- Government of Canada. Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2006. The Human Face of Mental Health and Mental Illness in Canada. p. 188 p. [Google Scholar]

- Steensma C, Loukine L, Orpana H, et al. Describing the population health burden of depression: health-adjusted life expectancy by depression status in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36((10)):201–09. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.10.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim K-L, Jacobs P, Ohinmaa A, Schopflocher D, Dewa CS. A new population-based measure of the economic burden of mental illness in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2008;28((3)):92–98. Available from: http:// publications.gc.ca/collections /collection_2009/aspc-phac/H12-27 -28-3E.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C, Janz T, Ali J. Ottawa (ON):: [released 2013 Sept 18; cited 2015 Sept 19]. Mental and substance use disorders in Canada [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www. s t a t c a n . g c . c a / p u b / 8 2 -624-x/2013001/article/11855 -eng.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Global burden of disease [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2012 [cited 2015 Sept 19] . Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo /global_burden_disease/gbd/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Survey on Disability, 2012. Fact sheet [Internet]. Statistics Canada. cited 2015 Sept 19] . Available from: http:// www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-654-x /89-654-x2013002-eng.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Article 1–Purpose [Internet]. United Nations. [cited 2016 Jul 29] . Available from: http:// www.un.org/disabilities/documents /convention/convoptprot-e.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Yaffe K, Lindquist K, Cherkasova E, Yelin E, Blazer DG. Depressive symptoms in middle age and the development of later-life functional limitations: the long-term effect of depressive symptoms. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Mar;;58((3)):551–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BS, Loeb M. Mood disorders and physical functioning difficulties as predictors of complex activity limitations in young U.S. adults. Disabil Health J. 2010 Jul;;3((3)):171–78. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Collings S. Gender and the association between mental disorders and disability. J Affect Disord. 2010;125((1-3)):207–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya M, Kawakami N, Ono Y, et al. Impact of mental disorders on work performance in a community sample of workers in Japan: the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2005. Psychiatry Res. 2012;198((1)):140–45. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny D. Unpublished [Google Scholar]

- Feeny D, Furlong W. Unpublished [Google Scholar]

- Breslin FC, Gnam W, Franche R-L, Mustard C, Lin E. Depression and activity limitations: examining gender differences in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41((8)):648–655. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier I, Beekman A, de Graaf R, Smit JH, van Dyck R, Penninx BW. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125((1-3)):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier I, de Graaf R, de Bruijn J, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders on-the-job: the importance of job characteristics for good work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2012 Dec;;200((2-3)):382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson K, Tilse E, Nicholson J, Oldenburg B, Graves N. Which presenteeism measures are more sensitive to depression and anxiety? J Affect Disord. 2007 Aug;;101((1–3)):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell S, Cheung R, Bennett K, Lagacé C. The 2014 Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada on Mood and Anxiety Disorders: a methodological overview. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36((12)):275–88. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.12.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada; 2014 June. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)–Annual Component: questionnaire. p. 373 p. [Google Scholar]

- Adams PF, Kirzinger WK, Martinez ME. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2013;10((259)) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsman J, Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G: The Health Utilities Index (HUI): concepts. measurement properties and applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1((54)):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Bernier J, McIntosh C, Orpana H. Validation of disability categories derived from Health Utilities Index Mark 3 scores. Health Rep. 2009 Jun;;20((2)):43–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2014. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)–Annual Component: derived variable (DV) specifications 2013. p. 117 p. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R. Bootstrap methods for standard errors, confidence intervals, and other measures of statistical accuracy. Statist Sci. 1986;1:54–75. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada; 2014 Oct. Ottawa (ON): Survey on Living with Chronic Diseases in Canada: user guide. p. 42 p. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264((19)):2524–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JA. Depression, disability and rehabilitation services for women. Psychol Women Q. 2003;27:121–29. [Google Scholar]

- el-Guebaly N, Currie S, Williams J, et al. Association of mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders with occupational status and disability in a community sample. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 May;;58((5)):659–67. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jean D, Giacomini M, Vanstone M, Brundisini F. Patient experiences of depression and anxiety with chronic disease: a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2013;13((16)):1–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin TP, Khandker RK, Kruzikas DT, Tummala R. Overlap of anxiety and depression in a managed care population: prevalence and association with resource utilization. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Aug;;67((8)):1187–93. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lépine JP. 4- discussion 11-2. 2001;62 Suppl 13: 10. Epidemiology, burden, and disability in depression and anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, D’Arcy C. Common and unique risk factors and comorbidity for 12-month mood and anxiety disorders among Canadians. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57((8)):479–87. doi: 10.1177/070674371205700806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;;62((6)):617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watterson RA, Williams JV, Lavorato DH, Patten SB. Epub ahead of print. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0706743716645304. [Google Scholar]

- Patten SB, Wang JL, Williams JV, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of major depression in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;;51((2)):84–90. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell S, Vanderloo S, McRae L, Onysko J, Patten SB, Pelletier L. Comparison of the estimated prevalence of mood and/or anxiety disorders in Canada between self-report and administrative data. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016 Aug;;25((4)):360–9. doi: 10.1017/S2045796015000463. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017 /S2045796015000463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2016. Report from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: mood and anxiety disorders in Canada, 2016. p. 44 p. [Google Scholar]

- Dewa CS, Lin E, Kooehoorn M, Goldner E. Association of chronic work stress, psychiatric disorders, and chronic physical conditions with disability among workers. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 May;;58((5)):652–8. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JL, Lesage A, Schmitz N, Drapeau A. The relationship between work stress and mental disorders in men and women: findings from a population-based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008 Jan;;62((1)):42–7. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.050591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha M. Statistics Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2013. Spotlight on Canadians: results from the General Social Survey: portrait of caregivers, 2012. p. [Catalogue No. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner A. Wilfrid Laurier University; Waterloo (ON): 2015. The lived experiences of sandwich generation women and their health behaviours [master’s thesis]. Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). Paper 1722. Available from: http://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2817 &context=etd. [Google Scholar]

- Humphries KH, van Doorslaer E. Income-related health inequality in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50((5)):663–71. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjepkema M, Wilkins R, Long A. Cause-specific mortality by education in Canada: a 16-year follow-up study. Health Rep. 2012;23((3)):3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier I, Beekman A, de Graaf R, Smit J, R. van Dyck R, Penninx B. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125((1-3)):198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisier I, de Graaf R, de Bruijn J, et al. Depressive and anxiety disorders on-the-job: the importance of job characteristics for good work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2012 Dec;;200((2-3)):382–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks SM, Spijker J, Licht CM, et al. Long-term work disability and absenteeism in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2015 Jun. 1;178:121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HealthPartners. HealthPartners. Available from: https://healthpartners.ca/sites/default/files/HealthPartners_Chronic_Disease_and_Mental_Health_Report_June17_2015.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Standards Association (CSA) and the Bureau de normalisation du Québec. CSA; Mississauga (ON): 2013 [cited 2015 Nov 12]. National standard of Canada for psychological health and safety in the workplace. p. 17 p. Available from: http://www .csagroup.org/documents/codes-and -standards/publications/CAN_CSA -Z1003-13_BNQ_9700-803_2013 _EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada; Calgary (AB): 2012. Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. p. 152 p. [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Available from: http://www.mentalhealthcommission .ca/sites/default/files/2016-06 /Workplace_MHCC_Aspiring _Workforce_Report_ENG_0.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Korkeila K, Suominen S, Ahvenainen J, et al. Non-response and related factors in a nation-wide health survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;17((11)):991–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1020016922473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Jamieson E, Walsh CA, et al. First Nations women’s mental health: results from an Ontario survey. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11((2)):109–15. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0004-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2006. The mental health and well-being of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. In: The human face of mental health and mental illness in Canada 2006. pp. 159–79. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc .ca/publicat/human-humain06/index -eng.php . [Google Scholar]

- Krausz RM, Clarkson AF, Strehlau V, Torchalla I, Li K, Schuetz CG. Mental disorder, service use, and barriers to care among 500 homeless people in 3 different urban settings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013 Aug;;48((8)):1235–43. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0649-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz D, Purandare N, Conn D. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older adults in long-term care homes: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010 Nov;;22((7)):1025–39. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AIF, McMaster JJ, Cohen SN. Challenges for Canada in meeting the needs of persons with serious mental illness in prison. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2013;41((4)):501–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C, Zamorski M, Janz T. Ottawa (ON):: 2014 [Catalogue No.: 82-624-X]. Mental health of the Canadian Armed Forces [Internet]. . Available from: http:// www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-624-x /2014001/article/14121-eng.htm . [Google Scholar]

- Conn D. An overview of common mental disorders among seniors. Writ Gerontol. 2002;18:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Schimmele CM, Chappell NL. Aging and late-life depression. J Aging Health. 2012;24((1)):3–28. doi: 10.1177/0898264311422599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]