Abstract

Reconstitution of a DNA fragment containing a 5S RNA gene from Xenopus borealis into a nucleosome greatly restricts binding of the primary 5S transcription factor, TFIIIA. Consistent with transcription experiments using reconstituted templates, removal of the histone tail domains stimulates TFIIIA binding to the 5S nucleosome greater than 100-fold. However, we show that tail removal increases the probability of 5S DNA unwrapping from the core histone surface by only approximately fivefold. Moreover, using site-specific histone-to-DNA cross-linking, we show that TFIIIA binding neither induces nor requires nucleosome movement. Binding studies with COOH-terminal deletion mutants of TFIIIA and 5S nucleosomes reconstituted with native and tailless core histones indicate that the core histone tail domains play a direct role in restricting the binding of TFIIIA. Deletion of only the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain dramatically stimulates TFIIIA binding to the native nucleosome, while further C-terminal deletions or removal of the tail domains does not lead to further increases in TFIIIA binding. We conclude that the unmodified core histone tail domains directly negatively influence TFIIIA binding to the nucleosome in a manner that requires the C-terminal transcription activation domain of TFIIIA. Our data suggest an additional mechanism by which the core histone tail domains regulate the binding of trans-acting factors in chromatin.

The highly evolutionarily conserved N-terminal tail domains of the core histones are known to play important roles in defining and stabilizing multiple levels of chromatin structure. These domains comprise approximately 20 to 25% of the mass of each core histone protein and contain an excess of lysine and arginine residues. Thus, the tails are thought to neutralize the negative charge associated with the phosphodiester backbone of DNA in chromatin, thereby increasing the stability of nucleosomes, condensed chromatin fibers, and higher order structures (8, 16). Some tail functions appear to be specific, as oligonucleosomes lacking the tail domains are unable to form fully condensed 30-nm chromatin fibers, even in solutions with elevated levels of divalent cations (1, 12, 14).

Compaction of eukaryotic DNA within chromatin directly influences critical nuclear activities, such as transcription, DNA replication, recombination, and DNA repair. The effect of chromatin on these processes is modulated by posttranslational modifications of the core histones, primarily within the core histone tails. These domains extend outside the main body of the nucleosome and provide targets for acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation, among other modifications (37, 40). These posttranslational modifications can either directly affect chromatin structure or provide recognition codes to direct the binding of ancillary proteins which alter the structural and functional state of the chromatin template or direct the binding of additional activities (25, 40). Such modifications can affect accessibility of DNA within individual nucleosomes (28, 43) or the stability of higher order chromatin structures (42). Thus, the core histone tail domains indirectly mediate accessibility of trans-acting factors to DNA within nucleosomes and chromatin.

DNA fragments containing a Xenopus borealis somatic-type 5S RNA gene have been used to study how the core histone tail domains affect the binding of a transcription factor to nucleosomal DNA in vitro (23, 36, 41, 45). Reconstitution of DNA fragments containing this gene with core histones yields nucleosomes in which a majority of the population adopts a unique translational position along the DNA, with the center of dyad symmetry located near the start site of transcription of the 5S gene (22, 36) (Fig. 1). Indeed, histone-DNA contacts within the 5S nucleosome can be detected throughout most of the 5S internal promoter, the cognate target of the primary 5S transcription factor, TFIIIA (Fig. 1) (23). Accordingly, binding of TFIIIA to the 5S gene assembled into a nucleosome is highly impeded (48). However, TFIIIA binding is greatly stimulated by the removal of H2A/H2B dimers from the 5S nucleosome (23) or acetylation or removal of the core histone tail domains (28, 45), consistent with results from other in vitro systems (30, 43, 44). Interestingly, removal of only the H3 and H4 tail domains is sufficient to restore high-affinity binding of TFIIIA to the nucleosome, while removal of the H2A or H2B tail domain has little effect on binding (45). However, while acetylation or removal of the tails drastically alters the ability of TFIIIA to bind the nucleosomal DNA, these modifications have only marginal effects on the stability of histone-DNA interactions within the nucleosome (7, 34). Thus, the mechanism by which histone tail acetylation or removal stimulates binding of TFIIIA is unclear.

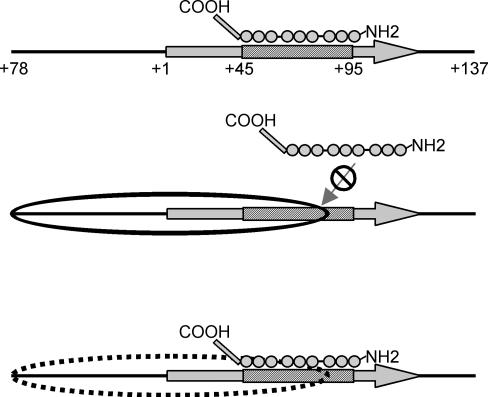

FIG. 1.

The core histone tail domains impede TFIIIA binding to the 5S nucleosome. Summary of how the core histone tail domains affect binding of the primary 5S transcription factor TFIIIA to a nucleosome containing a Xenopus somatic-type 5S rRNA gene. The 5S internal promoter (striped box) and the DNA region assembled into the nucleosome (oval) are indicated. Each of the nine zinc finger domains of TFIIIA (circles) and the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain (rectangle) are shown. TFIIIA is greatly restricted from binding to the nucleosome (solid-border oval) but binds with high affinity 5S nucleosomes lacking core histone tail domains (dashed-border oval) (28).

Here we present evidence that the core histone tails can influence binding of a transcription factor by a mechanism other than simple modulation of the stability of DNA wrapping in a nucleosome (7, 34) or the stability of higher order chromatin folding (17, 42). We find that the tail domains negatively influence TFIIIA binding to nucleosomes containing 5S DNA in a manner that depends on the C-terminal transcriptional activation domain of TFIIIA. These results highlight a potentially new way in which the tail domains may regulate transcription factor activity on chromatin substrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of radiolabeled DNA fragments.

A 215-bp DNA fragment was prepared from the plasmid pXP-10 and contains nucleotides −78 to +137 of an X. borealis somatic-type 5S RNA gene repeat (22). pXP-10 was digested with EcoRI (New England Biolabs), and then it was incubated with alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim) and subsequently phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) using [γ-32P]ATP. The radioactively labeled 215-bp fragment was produced by digestion with DdeI (New England Biolabs) and then was purified in 8% polyacrylamide gels in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer.

Preparation of 5S nucleosomes and H3/H4 tetramer-5S DNA complexes.

Core histones were purified from chicken erythrocytes as H2A/H2B dimers or H3/H4 tetramers (39). In addition, H2A, H2B, and the cysteine substitution mutants H2A-A12C and H2B-S56C (see Results) were expressed in Escherichia coli and then purified as H2A/H2B dimers (20, 29). Dimers containing H2A-A12C or H2B-S56C were modified with the cross-linking agent 4-azidophenacyl bromide (APB) as described previously (20, 29). Recombinant dimers were used in place of native proteins for nucleosome reconstitution, where indicated. 5S nucleosomes or H3/H4 tetramer-DNA complexes were reconstituted with the labeled 215-bp 5S DNA fragment by salt dialysis (48). To remove minor translational positions, reconstituted 5S nucleosomes (5 ml; ∼42.5 μg/ml) were concentrated to 1.0 ml by using a centrifugal filtration unit (Millipore Micron YM-50) and then were digested with 0.01 ml of BamHI (500 U/ml; New England Biolabs) for 15 min at 37°C (4). This effectively removes the radiolabel from nucleosomes occupying minor translational positions on the 5S DNA fragment (4). The nucleosomes were purified on sucrose gradients, and fractions containing nucleosomes were combined (2 ml total). Sucrose was then removed by repeated buffer exchange with 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0) through the filtration unit, and the sample was concentrated to 750 μl. To prepare tailless nucleosomes, 500 μl of the sample was incubated with trypsin-agarose beads (Sigma) for 15 min at room temperature and then briefly microcentrifuged (12 kg for 2 min) to remove the beads (45). Removal of core histone tail domains was verified by running a portion of the sample on sodium dodecyl sulfate-18% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-18% PAGE). Translational positions were analyzed by nondenaturing PAGE (5% polyacrylamide, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) electrophoresed at 106 V for 2 h at 25°C.

Restriction enzyme accessibility assays.

Restriction enzyme digestion of nucleosomes was carried out with an internal naked DNA control generated by digesting the 215-bp DNA fragment with RsaI to release a 154-bp fragment containing 5S sequences from −78 to +76 (7). Intact or tailless 5S nucleosomes and the 154-bp DNA fragment were incubated together with EcoRV (5,000 U/ml or 10 U/ml) or BbvI (600 U/ml or 10 U/ml) in the manufacturer's recommended buffer (New England BioLabs) for the times indicated in the legend to Fig. 2. The equilibrium constant describing the probability of nucleosomal DNA unwrapping (Kconfeq) was determined based on the rate of cleavage of naked versus nucleosomal DNA as described previously (7, 35).

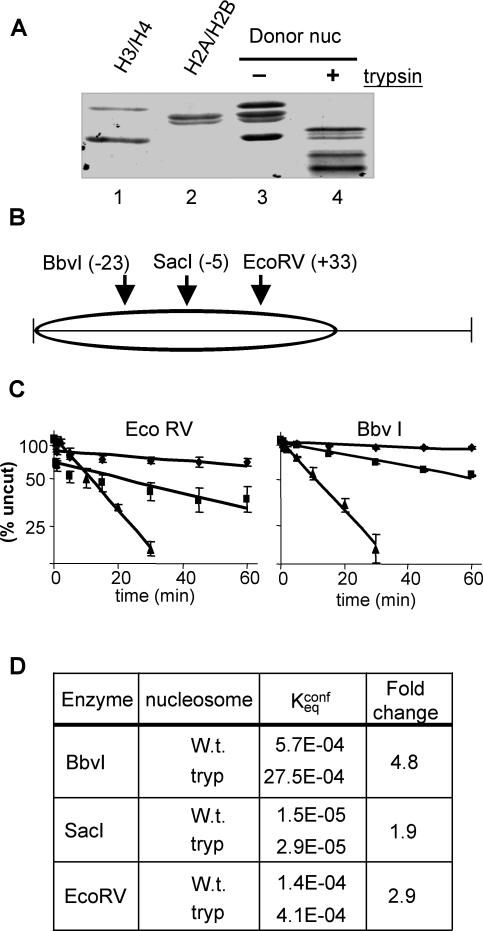

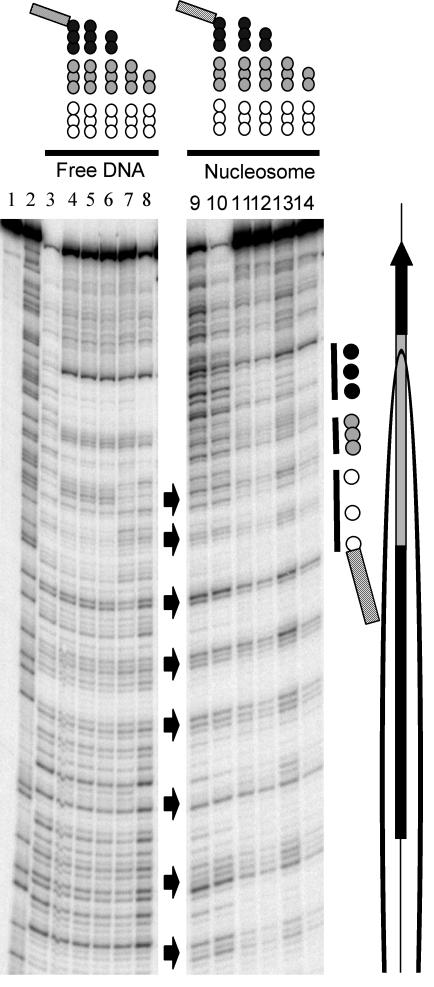

FIG. 2.

Spontaneous DNA unwrapping from the 5S nucleosome (nuc) is stimulated two- to fivefold upon removal of the core histone tail domains. Nucleosomes reconstituted with the 215-bp 5S DNA fragment were selected to eliminate minor translational positions, incubated with trypsin agarose beads to remove core histone tail domains, and digested with either EcoRV or BbvI. A 154-bp truncated 5S DNA fragment was included in each digest as a naked DNA reference. (A) Proteins within intact or tailless nucleosomes were examined on SDS-18% PAGE. Lane 1, (H3/H4)2 tetramer; lane 2, H2A/H2B dimer; lanes 3 and 4, intact or trypsinized 5S nucleosomes. (B) Schematic showing the locations of restriction enzyme sites used in this and a previous study (7). (C) Intact or tailless 5S nucleosomes and 154-bp DNA fragments were digested with the indicated enzymes, and the logarithm of the uncut fraction was plotted versus digestion times. Note that the nucleosomal curves were generated from digests containing 5,000 or 600 U of EcoRV or BbvI, respectively, while the naked DNA curves were generated from identical reaction mixtures containing 10-U/ml concentrations of each enzyme. Diamonds, intact nucleosome; squares, tailless nucleosome; and triangles, naked DNA. (C) Kconfeq and the relative increase in site exposure was determined as described previously (7). The SacI data was taken from reference 7. W.t. and tryp, intact and tailless nucleosomes, respectively.

Binding assays with TFIIIA and deletion mutants.

Labeled naked 5S DNA fragments or purified nucleosomes (∼3 ng each; ∼6,000 cpm total) were incubated with various dilutions of native and mutant TFIIIAs as described in the figure legends for 30 min at room temperature in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 70 mM NH4Cl, 7 mM MgCl2, 20 μM ZnCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.02% Nonidet P-40, 2 ng of bovine serum albumin/ml, 5% glycerol) in a total volume of 10 μl. The complexes were then separated by electrophoresis through 0.7% agarose nucleoprotein gels run in 0.5× TB buffer (0.045 M Tris base, 0.045 M borate) for 90 min at room temperature. The gels were dried and analyzed by a phosphorimager. The extent of binding was quantitated as described previously (41).

Mapping of cross-link positions.

Intact or tailless nucleosomes containing H2AA-12C-APB or H2B-S56C-APB were incubated in the absence or presence of TFIIIA. The resulting complexes were then separated by electrophoresis on 0.7% agarose nucleoprotein gels. Portions of the nucleosome samples were irradiated at 365 nm for 30 s before or after the removal of core histone tail domains and prior to TFIIIA binding. Another portion was irradiated directly in the gel after TFIIIA binding and electrophoresis. The DNA in each band of the agarose gel was purified and loaded into SDS-6% PAGE gels to separate cross-linked and non-cross-linked DNA. Radiolabeled species from each band were purified from the gel and then were treated with 1 M NaOH to cause DNA strand breaks at the sites of cross-linking, and products were separated on 6% sequencing gels. The gels were then dried, and cross-linking patterns were analyzed by a phosphorimager (29). Controls containing native histones were treated in the same manner.

DNase I footprinting.

Full-length TFIIIA or deletion mutants (∼100 ng) were incubated with the labeled naked 5S DNA fragment or purified nucleosomes (∼20 fmol each) in a total volume of 20 μl for 30 min at 25°C in TFIIIA binding buffer as described above. The reactions were treated with DNase I (0.04 U) for 3 min at 25°C and then were quenched by adding stop buffer (20 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS). Digested DNAs precipitated and separated on 6% sequencing gels, the gels dried, and cleavage patterns were analyzed by a phosphorimager. Alternatively, the proteins were incubated with reconstituted nucleosomes (∼40 fmol) in binding buffer in a total volume of 40 μl and treated with DNase I. The nucleosomes were then isolated on preparative nucleoprotein gels. After electrophoresis, the DNAs from each band were purified and cleavage patterns were analyzed as described above (48).

Purification of 3H-labeled TFIIIA and 1-9zf.

Bacteria containing TFIIIA or 1-9zf expression plasmids were grown in 50 ml of minimal medium at 37°C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reached approximately 0.6. Protein expression was then induced by addition of 20 μl of 1 M isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Thirty minutes after the induction, 2.5 ml of [3H]lysine (Net-3760; Perkin Elmer) was added, and the culture was further incubated for 3.5 h at 37°C. [3H]TFIIIA or [3H]1-9zf was purified by previously published methods (9, 10), and proteins were analyzed on SDS-12% PAGE. To determine the specificity and specific radioactivity of 3H incorporation into TFIIIA or 1-9zf peptide, samples were resolved on SDS-12%PAGE, gels were treated with 1 M salicylic acid for 10 min at room temperature, and the gels were dried and autoradiographed.

Binding assays with radiolabeled TFIIIA and deletion mutants.

A 304-bp DNA fragment containing the 5S RNA gene, including nucleotides −78 to +226, was cleaved from pXP10 by EcoRI and HindIII double digestion and then was purified on an 0.8% agarose gel. The fragment was further cleaved by DdeI digestion to 215-bp (−78 to +137) and 89-bp (+138 to +226) fragments. To reconstitute cold 5S nucleosomes, 5.6 μg of (H3/H4)2, 5.6 μg of H2A/H2B, and 10 μg of DNA templates (mixtures of 215- and 89-bp DNA fragments) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in 2 M NaCl buffer in a total volume of 400 μl, and then the sample was subjected to the standard salt dialysis method (48). To prepare cold, tailless 5S nucleosomes, reconstitutions were carried out as described above, except in a larger scale (6×) in a total volume of 2.4 ml, concentrated to 500 μl using a centrifugally based filter (YM-50; Millipore) and then treated with trypsin-agarose beads to cleave core histone tails as described previously (50).

Unlabeled intact or tailless 5S nucleosomes (0.5 nM) were incubated with decreasing amounts of [3H]TFIIIA or [3H]1-9zf and then were electrophoresed as described above. After electrophoresis, the agarose nucleoprotein gel was stained with ethidium bromide (1 μg/ml) for 20 min in 0.5× TB buffer containing 5% glacial acetic acid and 22.5% methanol. The gels were photographed upon UV illumination. The gels were then treated with 1 M salicylic acid for 10 min, dried, and exposed to film (KODAK BioMax XAR) for 10 to 14 days at −80°C. The autoradiographs were analyzed by densitometry. Apparent activity of the proteins was estimated from the point of 50% loading of the naked DNA template (9).

RESULTS

Stimulation of TFIIIA binding to the 5S nucleosome upon removal of the core histone tail domains is not due to an increase in the general accessibility of nucleosomal DNA.

Assembly of a DNA fragment containing an X. borealis 5S RNA gene into a nucleosome has been shown to greatly restrict the binding of TFIIIA (23, 41, 48), such that the affinity of TFIIIA for binding the nucleosome is at least 100-fold less than that for binding to free 5S DNA (45) (Fig. 1). In contrast to the large effect on TFIIIA binding, Chafin et al. previously found that removal of the core histone tail domains had a comparatively small effect on the probability of partial DNA unwrapping from the edge of the 5S nucleosome (7), consistent with other nucleosomes (34). To further investigate this issue, we determined the effect of removal of the tail domains on the probability of 5S DNA site exposure at two additional sites by using a sample of 5S nucleosomes highly enriched for a single translational position (4) (see Materials and Methods). EcoRV and BbvI sites are located about 30 and 40 bp, respectively, from each side of the dyad axis (Fig. 2B). The accessibility of EcoRV was increased 3-fold, while that of BbvI was increased 4.8-fold by the removal of the tail domains (Fig. 2C and D), consistent with previous data (7, 35). Moreover, we note that hydroxyl radical footprints of native and tailless nucleosomes do not indicate extensive changes in histone-DNA interactions upon tail removal (6, 23). Thus, the large enhancement of TFIIIA binding upon tail removal does not appear to be due to a drastic increase in DNA unwrapping from the edge of the nucleosome.

TFIIIA binding does not require or induce nucleosome movement.

We next considered the possibility that tail removal facilitates nucleosome repositioning upon TFIIIA binding, resulting in greater exposure of the internal promoter. To this end, nucleosomes were reconstituted with one histone modified with a photoactivatable cross-linking agent to allow the position of the nucleosome before and after TFIIIIA binding to be ascertained. Nucleosomes containing derivatized H2A (H2A-A12C-APB) were reconstituted, and then a portion of the sample was treated with trypsin-agarose beads to remove the core histone tails. The binding of TFIIIA to nucleosomes containing H2A-A12C-APB is highly stimulated by tail removal in a manner identical to that observed with native histones (46). Similar results were obtained when the cross-linker was located within the histone fold domain of H2B (H2B-S56C-APB; see below). The nucleosomes containing APB-modified histones were then used to examine whether the binding of TFIIIA induces nucleosome movement, leading to greater exposure of the internal promoter. It was previously shown that the fraction of DNA cross-linked in H2A-A12C-APB-containing 5S nucleosomes bound by TFIIIA was similar to that of unbound nucleosomes (46). This suggests that TFIIIA does not require nucleosome movement as a prerequisite to binding, because cross-linked nucleosomes are expected to be severely restricted in their ability to slide along the DNA (3). To verify this result and to determine if different translational positions within the cross-linked population are perhaps selectively bound by TFIIIA, 5S nucleosomes containing H2A-A12C-APB were irradiated before tail removal by trypsinization, and then TFIIIA-bound and unbound fractions were isolated from preparative nucleoprotein gels and positions of cross-links were determined by base elimination (Fig. 3A). (Note that about 20% of the sample is cross-linked.) As expected because samples were irradiated before trypsinization, identical cross-linking patterns were observed for both the intact and tailless nucleosomes (Fig. 3B, lanes 5 and 6); a major cross-link at position +40 corresponds to the main translational position of the nucleosome, while a signal at +60 corresponds to a possible minor position (4, 7). Importantly, the positions and yields of cross-links were identical in both the TFIIIA-bound and unbound nucleosome fractions (Fig. 3B, lanes 6 and 7), indicating that TFIIIA does not selectively bind to non-cross-linked nucleosomes or any particular translational position. Unexpectedly, when the H2A-A12C-APB-containing nucleosomes were irradiated after the removal of core histone tail domains, we observed that the positions of cross-links were drastically altered (Fig. 3B, lane 8), with cross-links now appearing at positions +120, +107, +98, +35, −1, and −30. These data suggest that removal of the core histone tail domains affects the positioning and mobility of histone octamer on 5S DNA (15; Z. Yang and J. J. Hayes, unpublished data). Nevertheless, cross-linking patterns obtained before and after TFIIIA binding (Fig. 3B, lanes 8 and 9) are virtually identical, indicating that further nucleosome movement is not induced upon TFIIIA binding to the tailless 5S nucleosome.

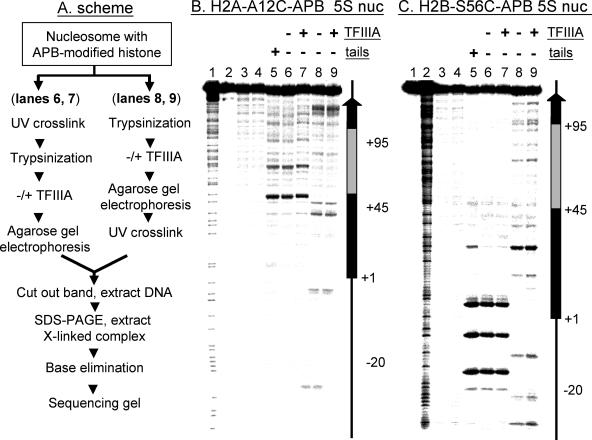

FIG. 3.

TFIIIA binding does not induce or require nucleosome (nuc) repositioning. Intact or tailless 5S nucleosomes containing H2A-A12C-APB or H2B-S56C-APB were prepared, and the translational positions of the nucleosomes were determined before and after TFIIIA binding. Alternatively, the effect of fixing the translational position of the nucleosome by cross-linking on subsequent TFIIIA binding was examined. (A) Experimental scheme. (B and C) Analysis of cross-linked products from nucleosomes containing H2A-A12C-APB or H2B-S56C-APB, respectively, on 6% sequencing gels. (B and C) Lanes 1 and 2, G-reaction marker and free DNA not treated with NaOH; lanes 3 and 4, naked 5S DNA and native nucleosome cross-linking controls treated with NaOH; lane 5, cross-linking within nucleosomes containing H2A-A12C-APB or H2B-S56C-APB, respectively; lanes 6 to 9, tailless H2A-A12C-APB or H2B-S56C-APB nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in lanes 6 and 7 were irradiated before trypsinization, incubated without or with TFIIIA as indicated, and the complexes were isolated from a nucleoprotein gel. Nucleosomes in lanes 8 and 9 were irradiated after trypsinization, TFIIIA binding, and gel electrophoresis (see the text for details). The locations of internal promoter and 5S gene are indicated (right).

To substantiate these results, the cross-linking experiments were repeated with nucleosomes containing H2B-S56C-APB, in which an amino acid in the histone fold domain of H2B was mutated to cysteine and modified with APB (26). When these nucleosomes were irradiated before removal of the core histone tail domains, we again found that TFIIIA did not selectively bind to non-cross-linked nucleosomes or a subset of cross-linked nucleosomes (Fig. 3C, lanes 6 and 7). As before, we also found that after removal of the tails, the positions and yields of cross-links were drastically altered (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 6 and 8). However, the cross-linking pattern was again identical in TFIIIA-bound and unbound tailless nucleosomes (Fig. 3C, lanes 8 and 9). Together, results from cross-linking experiments indicate that while removal of the core histone tail domains does affect nucleosome positioning along the DNA (15), nucleosome movement is neither induced by nor is required for TFIIIA binding to the tailless nucleosome.

COOH-terminal deletion mutants of TFIIIA bind to the 5S nucleosome with high affinity.

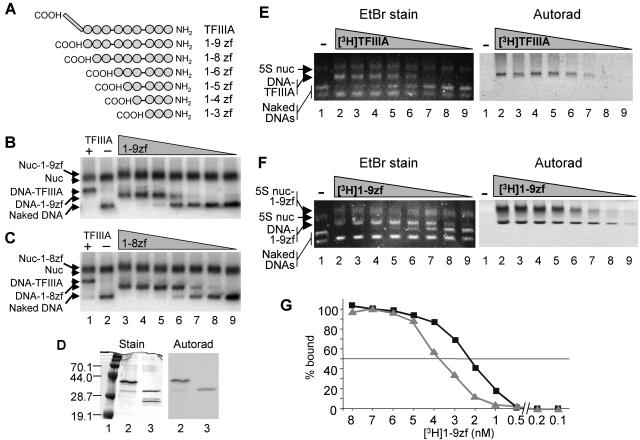

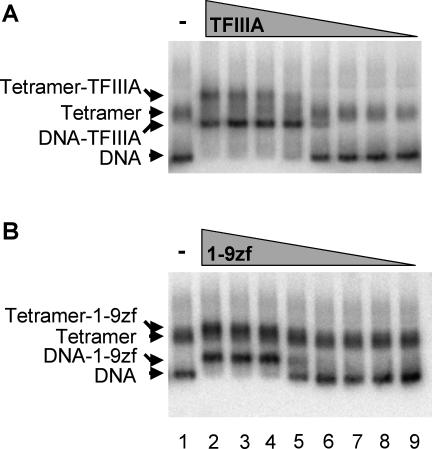

Having eliminated the possibility that removal of the tail domains causes a significant increase in the stability of DNA wrapping within the nucleosome or allows TFIIIA-induced nucleosome mobilization, we next investigated the possibility that a domain or region within TFIIIA may restrict binding to the nucleosome, possibly via direct interaction with some element of nucleosome structure, such as the core histone tail domains. Given the orientation of TFIIIA at the downstream edge of the nucleosome (Fig. 1), we first determined whether any of six COOH-terminal deletion mutants of TFIIIA containing zinc fingers 1 to 9, 1 to 8, 1 to 6, 1 to 5, 1 to 4, or 1 to 3 (9) (Fig. 4A) exhibit binding to the 5S nucleosome by gel shift assays. Binding studies with the zinc finger 1 to 9 peptide (1-9zf), lacking only the 7-kDa COOH-terminal transcription activation domain, revealed a small but detectable shift in the position of the naked 5S DNA and nucleosome bands on the gel, suggesting that this peptide bound both with high affinity to both species (Fig. 4B). Likewise, a peptide containing zinc fingers 1 to 8 also appeared to bind to the 5S nucleosome with similar affinity but also produced a small shift in the position of the nucleosome on the gel (Fig. 4C). The remaining zinc finger deletion mutants exhibited similar behavior in the nucleosome binding assays (results not shown). In contrast, TFIIIA bound to the naked DNA fragment but apparently did not bind to the nucleosome, consistent with previous results (23, 28, 45). To substantiate binding of the deletion mutants to the 5S nucleosomes, we repeated the electrophoretic mobility shift assay with radiolabeled TFIIIA and 1-9zf peptide and unlabeled nucleosomes (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 4D). The autoradiograph clearly shows that TFIIIA is bound to the naked DNA fragment containing the 5S gene but does not associate with a nonspecific 89-bp DNA fragment or with the 5S DNA nucleosome (Fig. 4E). In contrast, the 1-9zf radiolabeled peptide clearly associates with both the naked 5S DNA fragment and the 5S nucleosome (Fig. 4F). These data indicate that removal of only the C-terminal activation domain of TFIIIA results in a large stimulation of TFIIIA binding to the native, unmodified 5S nucleosome, while further deletions had little or no additional effect on relative binding affinity.

FIG. 4.

COOH-terminal deletion mutants of TFIIIA bind to the unmodified 5S nucleosome with high affinity. 5S nucleosomes (nuc) containing unmodified, native histones were incubated with TFIIIA deletion mutants (9), and binding was assessed by nucleoprotein gel shift. (A) Schematic of the TFIIIA deletion mutants showing the COOH-terminal activation domain (rectangle) and zinc fingers (circles). (B and C) Comparison of the binding of full-length TFIIIA and COOH-terminal deletion mutants to that of radiolabeled naked 5S DNA and 5S nucleosomes. Lanes 1 and 2, 5S nucleosomes and naked DNA incubated with or without TFIIIA, respectively; lanes 3 to 9, nucleosomes and naked DNA incubated with 50, 25, 12.5, 6, 3, 1.5, or 0.75 ng of either the 1-9zf (B) or 1-8zf (C) peptide. (D) Preparations of radiolabeled full-length TFIIIA and 1-9zf peptide. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2 and 3, TFIIIA and 1-9zf peptide preparations. (E and F) Comparisons of the binding of radiolabeled TFIIIA and 1-9zf peptide to that of unlabeled naked 5S DNA and 5S nucleosomes. All lanes contain naked 5S DNA, 5S nucleosomes, and a nonspecific 89-bp naked DNA fragment. Lanes 1 to 9 contain 0, 4, 3.5, 3, 2.5, 2, 1.5, 1, and 0.5 ng, respectively, of TFIIIA or 1-9zf. (G) The percentage of 1-9zf protein bound to naked DNA (squares) or nucleosomes (triangles) in panel F was quantified and plotted versus the apparent activity of the 1-9zf peptide. The maximum density of bound peptide was taken as 100%. EtBr, ethidium bromide; Autorad, autoradiography.

To further substantiate these results, we performed DNase I footprinting studies with full-length TFIIIA and the deletion mutants. Previous studies have shown that nucleotides from +45 to +96 on the noncoding strand of the 5S RNA gene are protected from DNase I cleavage by the binding of TFIIIA (13) and that this footprint is truncated in a linear fashion as fingers are deleted from the COOH end of the protein (9, 47). Free 5S DNA and 5S nucleosomes purified on sucrose gradients were incubated with TFIIIA or the zinc finger 1 to 9, 1 to 8, 1 to 6, and 1 to 5 peptides. The complexes were digested with DNase I, and cleavage patterns were analyzed on sequencing gels. The TFIIIA binding site on naked 5S DNA was clearly protected in the presence of full-length TFIIIA and the zinc finger 1 to 9 and 1 to 8 peptides (Fig. 5, lanes 4 to 6), while nucleotides from +92 to +75 or +71 to +61 were protected when the zinc finger 1 to 6 or 1 to 5 peptide was incubated with 5S DNA, respectively (lanes 7 and 8). As expected, no binding was detected when the 5S nucleosome was incubated with full-length TFIIIA (Fig. 5, lane 10). However, in striking contrast, a clear footprint was observed when the TFIIIA deletion mutants were incubated with the 5S nucleosome containing full-length core histones (lanes 11 to 14). Note that periodic cleavage patterns due to core histone-DNA interactions are observed immediately adjacent to the TFIIIA footprints. Similar results were obtained when ternary complexes treated with DNase I were isolated on nucleoprotein gels prior to sequencing gel electrophoresis (results not shown). These results indicate that, unlike native TFIIIA, all of the TFIIIA deletion mutants lacking the COOH transcription activation domain bind specifically and with high affinity to 5S nucleosomes containing unmodified, full-length core histone proteins.

FIG. 5.

TFIIIA deletion mutants bind to the native 5S nucleosome. Purified 5S nucleosomes containing native, unmodified core histones were incubated with the indicated proteins, and binding was assessed by DNase I footprinting and sequencing gel electrophoresis. Lane 1, naked 5S DNA fragment; lane 2, G-reaction marker; lanes 3 to 8 or 9 to 14, footprints of naked 5S DNA or nucleosomes, respectively, without protein or with TFIIIA, 1-9zf, 1-8zf, 1-6zf, and 1-5zf, respectively, as indicated.

The C-terminal activation domain of TFIIIA affects the migration of the 5S tetramer-TFIIIA complex.

In the gel shift experiments, the binding of the TFIIIA deletion mutants causes a rather small but detectable shifting of the nucleosome band on the gel (Fig. 4 and results not shown). Previous data have shown that when full-length TFIIIA binds to acetylated or tailless 5S nucleosomes, the complex is obviously shifted upwards on the gel in relation to the free nucleosome (28, 41, 45). Although the C-terminal activation domain comprises approximately 20% of the mass of TFIIIA, it is possible that it has a large effect on the migration of the 5S nucleosome-TFIIIA ternary complex. To assess the contribution of the C-terminal activation domain to the migration of these complexes, H3/H4 tetramer-5S DNA complexes were reconstituted. TFIIIA binds to the 5S tetramer with high affinity, likely because most of the TFIIIA binding site is more exposed than it is in the 5S nucleosome (23, 28). Indeed, addition of increasing amounts of TFIIIA yields TFIIIA-5S tetramer complexes that were obviously shifted compared to the unbound 5S tetramer (Fig. 6A). Likewise, as increasing amounts of the zinc finger 1 to 9 peptide were added, all free DNA as well as all 5S tetramer complexes were apparently bound, but these complexes were shifted to a much smaller extent compared to the shift induced by binding of full-length TFIIIA (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that the C-terminal activation domain of TFIIIA has a proportionately large effect on the migration of the ternary complex through the nucleoprotein gels, while the nine-zinc-finger DNA binding domain, which comprises 80% of the mass of the protein, causes only a modest change in the migration of the nucleosome. These data are consistent with models in which the nine-zinc-finger domain binds very compactly along the 5S internal promoter (9, 21, 32), whereas the C-terminal activation domain projects away from the complex to provide an unobstructed binding surface for transcription factor TFIIIC (18, 27).

FIG. 6.

The 1-9zf peptide binds to the 5S H3/H4-tetramer complex but causes a very small electrophoretic mobility shift. 5S DNA-H3/H4 tetramer complexes were incubated with either full-length TFIIIA (A) or the 1-9zf protein (B). Lane 1 contains the tetramer-DNA complexes incubated without protein; lanes 2 to 9, tetramer-DNA complexes incubated with decreasing amounts of TFIIIA or the 1-9zf peptide as described in the legend to Fig. 4B.

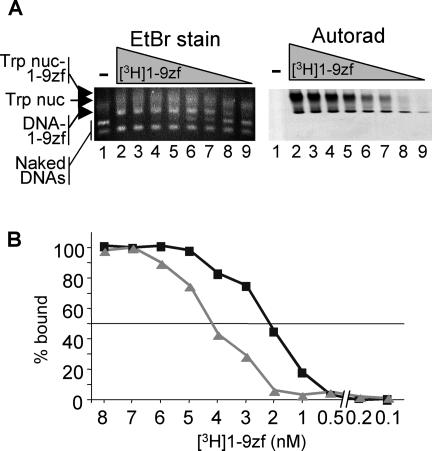

Binding of zinc finger 1 to 9 peptide to the 5S nucleosome is not affected by core histone tail domains.

The above results suggest that the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain negatively interacts with a nucleosomal component and that this negative interaction is eliminated when the tail domains are removed. Interestingly, we noted that the affinity with which the zinc finger 1 to 9 peptide binds to the 5S tetramer was similar to the affinity with which this peptide binds free DNA, while full-length TFIIIA binds the 5S tetramer with an affinity approximately three- to fourfold lower than that for binding free DNA (Fig. 6 and results not shown). This suggests that the C-terminal activation domain has a small negative influence on TFIIIA binding, even with the 5S tetramer. To further investigate this issue, we examined the effect of the tails on the binding of the radiolabeled 1-9zf peptide to 5S nucleosomes containing or lacking the core histone tail domains. The 1-9zf peptide binds to 5S nucleosomes with an affinity two to three times less than that for naked DNA, regardless of the presence or absence of the tails (compare Fig. 7 and 4G).

FIG. 7.

Binding of the 1-9zf peptide to the 5S nucleosome is not dependent on the core histone tails. Nucleosomes were reconstituted and treated with trypsin to remove the histone tail domains, and the binding of 1-9zf peptide was then assessed by gel mobility shift and autoradiography (Autorad). (A) Comparison of binding of the radiolabeled 1-9zf peptide to unlabeled 5S DNA and tailless 5S nucleosomes. (B) The percentage of 1-9zf peptide bound to naked DNA (squares) or tailless 5S nucleosomes (triangles) is plotted versus the apparent activity of the peptide. The maximum density of bound peptide was taken as 100%. EtBr, ethidium bromide.

DISCUSSION

We present evidence that the core histone tail domains negatively influence TFIIIA binding to the 5S nucleosome via a mechanism that involves the COOH transcription activation domain of TFIIIA. Removal of this domain does not affect TFIIIA binding to naked DNA. However, the affinity with which TFIIIA binds to the 5S nucleosome is enhanced at least 100-fold by the removal of the C-terminal activation domain of TFIIIA or the removal of the core histone tails (Fig. 1 and 4). Removal of both tail domains and the COOH transcription activation domain does not result in a further increase in TFIIIA binding activity (Fig. 4 and 7). The large increase in affinity caused by tail removal cannot be accounted for by a simple decrease in the stability of DNA association with histones (i.e., the probability of spontaneous DNA unwrapping from the nucleosome) (Fig. 2). Indeed, site exposure in the 5S nucleosome or other nucleosomes is only increased two- to fivefold by the removal of core histone tail domains (7, 35).

The negative influence of the core histone tails may be due to steric hindrance between these domains and the COOH transcription activation domain of TFIIIA when the protein attempts to invade the nucleosome. Alternatively, the tails may actually associate with this domain in a manner that reduces the potential for productive DNA binding by the remainder of the protein. TFIIIA binds in a linear fashion to the 50-bp internal promoter, with the C-terminal transcription activation oriented toward the interior of the nucleosome binding site, in position to interact with selected tail domains (46). In addition, the C-terminal domain has been shown to modulate the stability of TFIIIA binding. Specifically, TFIIIC binds to the TFIIIA-DNA complex and greatly stabilizes TFIIIA association in a manner dependent upon the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain (18, 49). However, the exact molecular mechanism by which the unmodified tails, in conjunction with the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain, reduce the binding activity of TFIIIA remains unclear.

It has been well established that the tails indirectly mediate the accessibility of nucleosomal DNA. They affect stability of DNA wrapping within the nucleosome (5, 34) and are required for the folding of oligonucleosomal arrays into chromatin fibers (1, 14) and for mediating fiber-fiber association, perhaps relevant to higher order chromatin structures (16, 38). Our data suggest a new, direct mechanism by which the tail domains may regulate the association of critical trans-acting factors with nucleosomal DNA. Moreover, it has been reported that, similar to tail removal, acetylation of the core histone tail domains greatly stimulates TFIIIA binding (28) and that transcriptionally active somatic-type 5S genes in vivo are associated with acetylated histones while inactive 5S genes are not (24). Our data raise the possibility that acetylation of tails reduces negative interactions between these domains and the COOH-terminal domain of TFIIIA, perhaps by eliminating the positive charge of critical lysines within the tails.

There are at least two general mechanisms for how TFIIIA (and other similar factors) may invade the nucleosome and bind to its target site. One possibility is that binding is coupled to the spontaneous unwrapping of DNA from the edge of the nucleosome to partially or fully expose the binding site (35). In the case of TFIIIA, such binding may be initiated at the edge of the nucleosome by the first (most N-terminal) zinc finger, and then histone-DNA interactions are sequentially detached while the remaining fingers associate with their cognate sites (46). This may allow for a gradual unpeeling of the DNA from the histone surface. A second possibility is that the binding of TFIIIA is coupled to movement of histone octamer along the 5S RNA gene, resulting in exposure of the internal promoter. However, our cross-linking data clearly show that TFIIIA binding to the nucleosome does not require or induce nucleosome movement (Fig. 3). Moreover, recent results show that nucleosome mobility is negligible compared to site exposure by DNA release from the histone surface, especially in buffers that contain Mg2+ (2).

Generally, the positioning of nucleosomes has been thought not to be dependent on the core histone tail domains (11, 19). However, recent evidence indicates that the tails can affect nucleosome positioning and mobility (15, 31). Here we observed that the core histone tails drastically affect the positioning and mobility of the 5S nucleosomes by using a highly sensitive cross-linking technique to map positions before and after removal of the tail domains (Fig. 3B and C and Yang and Hayes, unpublished data). Note that in our experiment, bona fide nucleosome movement is detected upon removal of the tail domains from canonical nucleosomes. However, this mobility was not required for TFIIIA binding to the tailless nucleosome, as nucleosomes cross-linked before tail removal bound TFIIIA as efficiently as non-cross-linked nucleosomes. Moreover, cross-linking after complex formation revealed that TFIIIA binding had little effect on the final position of the tailless nucleosome. These results suggest that the critical parameter with respect to TFIIIA binding to the nucleosome appears to be the lack of the core histone tail domains or the COOH-terminal transcription activation domain of TFIIIA and not the precise position of the nucleosome, as has been suggested previously (33). Nevertheless, a detailed molecular understanding of the role of the histone tails in defining nucleosome position is not yet available.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joel Gottesfeld (Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute) for providing the TFIIIA deletion mutants and plasmids.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM52426.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan, J., N. Harborne, D. C. Rau, and H. Gould. 1982. Participation of the core histone tails in the stabilization of the chromatin solenoid. J. Cell Biol. 93:285-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, J. D., A. Thastrom, and J. Widom. 2002. Spontaneous access of proteins to buried nucleosomal DNA target sites occurs via a mechanism that is distinct from nucleosome translocation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7147-7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aoyagi, S., and J. J. Hayes. 2002. hSWI/SNF-catalyzed nucleosome sliding does not occur solely via a twist diffusion mechanism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7484-7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoyagi, S., P. A. Wade, and J. J. Hayes. 2003. Nucleosome sliding catalyzed by the xMi-2 complex does not occur exclusively via a simple twist-diffusion mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 278:30562-30568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ausio, J., F. Dong, and K. E. van Holde. 1989. Use of selectively trypsinized nucleosome core particles to analyze the role of the histone “tails” in the stabilization of the nucleosome. J. Mol. Biol. 206:451-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bauer, W. R., J. J. Hayes, J. H. White, and A. P. Wolffe. 1994. Nucleosome structural changes due to acetylation. J. Mol. Biol. 236:685-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chafin, D. R., J. M. Vitolo, L. A. Henricksen, R. A. Bambara, and J. J. Hayes. 2000. Human DNA ligase I efficiently seals nicks in nucleosomes. EMBO J. 19:5492-5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark, D. J., and T. Kimura. 1990. Electrostatic mechanism of chromatin folding. J. Mol. Biol. 211:883-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens, K. R., X. Liao, V. Wolf, P. E. Wright, and J. M. Gottesfeld. 1992. Definition of the binding sites of individual Zn-fingers in the transcription factor IIIA-5S RNA gene complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10822-10826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del Rio, S., and D. R. Setzer. 1991. High yield purification of active transcription factor IIIA expressed in E. coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6197-6203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong, F., J. C. Hansen, and K. E. van Holde. 1990. DNA and protein determinants of nucleosome positioning on sea urchin 5S rRNA gene sequences in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:5724-5728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dorigo, B., T. Schalch, K. Bystricky, and T. J. Richmond. 2003. Chromatin fiber folding: requirement for the histone H4 N-terminal tail. J. Mol. Biol. 327:85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engelke, D. R., S.-Y. Ng, B. S. Shastry, and R. G. Roeder. 1980. Specific interaction of a purified transcription factor with an internal control region of 5S RNA genes. Cell 19:717-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Ramirez, M., F. Dong, and J. Ausio. 1992. Role of the histone “tails” in the folding of oligonucleosomes depleted of histone H1. J. Biol. Chem. 267:19587-19595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamiche, A., J. G. Kang, C. Dennis, H. Xiao, and C. Wu. 2001. Histone tails modulate nucleosome mobility and regulate ATP-dependent nucleosome sliding by NURF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:14316-14321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen, J. C. 2002. Conformational dynamics of the chromatin fIber in solution: determinants, mechanisms, and functions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31:361-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen, J. C., and A. P. Wolffe. 1992. Influence of chromatin folding on transcription initiation and elongation by RNA polymerase III. Biochemistry 31:7977-7988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayes, J., T. D. Tullius, and A. P. Wolffe. 1989. A protein-protein interaction is essential for stable complex formation on a 5S RNA gene. J. Biol. Chem. 264:6009-6012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayes, J. J., D. J. Clark, and A. P. Wolffe. 1991. Histone contributions to the structure of DNA in the nucleosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:6829-6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes, J. J., and K. M. Lee. 1997. In vitro reconstitution and analysis of mononucleosomes containing defined DNAs and proteins. Methods 12:2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes, J. J., and T. D. Tullius. 1992. The structure of the TFIIIA/5S DNA complex. J. Mol. Biol. 227:407-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayes, J. J., T. D. Tullius, and A. P. Wolffe. 1990. The structure of DNA in a nucleosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7405-7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes, J. J., and A. P. Wolffe. 1992. Histones H2A/H2B inhibit the interaction of transcription factor IIIA with the Xenopus borealis somatic 5S RNA gene in a nucleosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:1229-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe, L., T. A. Ranalli, C. D. Allis, and J. Ausio. 1998. Transcriptionally active Xenopus laevis somatic 5S ribosomal RNA genes are packaged with hyperacetylated histone H4, whereas transcriptionally silent oocyte genes are not. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20693-20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenuwein, T., and C. D. Allis. 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kassabov, S. R., N. M. Henry, M. Zofall, T. Tsukiyama, and B. Bartholomew. 2002. High-resolution mapping of changes in histone-DNA contacts of nucleosomes remodeled by ISW2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7524-7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lassar, A. B., P. L. Martin, and R. G. Roeder. 1983. Transcription of class III genes: formation of preinitiation complexes. Science 222:740-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, D. Y., J. J. Hayes, D. Pruss, and A. P. Wolffe. 1993. A positive role for histone acetylation in transcription factor access to nucleosomal DNA. Cell 72:73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee, K. M., D. R. Chafin, and J. J. Hayes. 1999. Targeted cross-linking and DNA cleavage within model chromatin complexes. Methods Enzymol. 304:231-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lefebvre, P., A. Mouchon, B. Lefebvre, and P. Formstecher. 1998. Binding of retinoic acid receptor heterodimers to DNA. A role for histones NH2 termini. J. Biol. Chem. 273:12288-12295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lomvardas, S., and D. Thanos. 2001. Nucleosome sliding via TBP DNA binding in vivo. Cell 106:685-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nolte, R. T., R. M. Conlin, S. C. Harrison, and R. S. Brown. 1998. Differing roles for zinc fingers in DNA recognition: structure of a six-finger transcription factor IIIA complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:2938-2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panetta, G., M. Buttinelli, A. Flaus, T. J. Richmond, and D. Rhodes. 1998. Differential nucleosome positioning on Xenopus oocyte and somatic 5 S RNA genes determines both TFIIIA and H1 binding: a mechanism for selective H1 repression. J. Mol. Biol. 282:683-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polach, K. J., P. T. Lowary, and J. Widom. 2000. Effects of core histone tail domains on the equilibrium constants for dynamic DNA site accessibility in nucleosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 298:211-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polach, K. J., and J. Widom. 1995. Mechanism of protein access to specific DNA sequences in chromatin: a dynamic equilibrium model for gene regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 254:130-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rhodes, D. 1985. Structural Analysis of a triple complex between the histone octamer, a Xenopus gene for 5S RNA and transcription factor IIIA. EMBO J. 4:3473-3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth, S. Y., J. M. Denu, and C. D. Allis. 2001. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:81-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarz, P. M., A. Felthauser, T. M. Fletcher, and J. C. Hansen. 1996. Reversible oligonucleosome self-association: dependence on divalent cations and core histone tail domains. Biochemistry 35:4009-4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R. H., and G. Felsenfeld. 1979. A new procedure for purifying histone pairs H2A + H2B and H3 + H4 from chromatin using hydroxylapatite. Nucleic Acids Res. 6:689-696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strahl, B. D., and C. D. Allis. 2000. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403:41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thiriet, C., and J. J. Hayes. 1998. Functionally relevant histone-DNA interactions extend beyond the classically defined nucleosome core region. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21352-21358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tse, C., T. Sera, A. P. Wolffe, and J. C. Hansen. 1998. Disruption of higher-order folding by core histone acetylation dramatically enhances transcription of nucleosomal arrays by RNA polymerase III. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4629-4638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vettese-Dadey, M., P. A. Grant, T. R. Hebbes, C. Crane-Robinson, C. D. Allis, and J. L. Workman. 1996. Acetylation of histone H4 plays a primary role in enhancing transcription factor binding to nucleosomal DNA in vitro. EMBO J. 15:2508-2518. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vettese-Dadey, M., P. Walter, H. Chen, L. J. Juan, and J. L. Workman. 1994. Role of the histone amino termini in facilitated binding of a transcription factor, GAL4-AH, to nucleosome cores. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:970-981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vitolo, J. M., C. Thiriet, and J. J. Hayes. 2000. The H3-H4 N-terminal tail domains are the primary mediators of transcription factor IIIA access to 5S DNA within a nucleosome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:2167-2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vitolo, J. M., Z. Yang, R. Basavappa, and J. J. Hayes. 2004. Structural features of transcription factor IIIA bound to a nucleosome in solution. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:697-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vrana, K. E., M. E. Churchill, T. D. Tullius, and D. D. Brown. 1988. Mapping functional regions of transcription factor TFIIIA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:1684-1696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolffe, A. P., G. Almouzni, K. Ura, D. Pruss, and J. J. Hayes. 1993. Transcription factor access to DNA in the nucleosome. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 58:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolffe, A. P., and D. D. Brown. 1988. Developmental regulation of two 5S ribosomal RNA genes. Science 241:1626-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang, Z., and J. J. Hayes. 2004. Large scale preparation of nucleosomes containing site-specifically chemically modified histones lacking the core histone tail domains. Methods 33:25-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]