Abstract

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase) complex functions as a coactivator during Gal4-activated transcription. A functional interaction between the SAGA component Spt3 and TATA-binding protein (TBP) is important for TBP binding at Gal4-activated promoters. To better understand the role of SAGA and other factors in Gal4-activated transcription, we selected for suppressors that bypass the requirement for SAGA. We obtained eight complementation groups and identified the genes corresponding to three of the groups as NHP10, HDA1, and SRB9. In contrast to the srb9 suppressor mutation that we identified, an srb9Δ mutation causes a strong defect in Gal4-activated transcription. Our studies have focused on this requirement for Srb9. Srb9 is part of the Srb8-Srb11 complex, associated with the Mediator coactivator. Srb8-Srb11 contains the Srb10 kinase, whose activity is important for GAL1 transcription. Our data suggest that Srb8-Srb11, including Srb10 kinase activity, is directly involved in Gal4 activation. By chromatin immunoprecipitation studies, Srb9 is present at the GAL1 promoter upon induction and facilitates the recruitment or stable association of TBP. Furthermore, the association of Srb9 with the GAL1 upstream activation sequence requires SAGA and specifically Spt3. Finally, Srb9 association also requires TBP. These results suggest that Srb8-Srb11 associates with the GAL1 promoter subsequent to SAGA binding, and that the binding of TBP and Srb8-Srb11 is interdependent.

The SAGA (Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase) complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a large multiprotein complex that is required for the normal transcription of many genes and is conserved from yeast to humans (27, 34, 54). The SAGA complex functions in vivo as a coactivator for transcriptional activation by the Gal4 protein, playing a key role in activating genes that allow S. cerevisiae to metabolize galactose as a carbon source (9, 32). Past work has shown that upon induction by galactose, Gal4 recruits SAGA and the Spt3 component of SAGA facilitates TBP binding to the GAL1 promoter (9, 10, 12, 18, 32). Spt3 has also recently been implicated in nucleosome remodeling (59).

Mutations in genes encoding structural components of SAGA, such as SPT20, cause a severe Gal− phenotype (51, 57). However, after prolonged galactose induction, spt20Δ mutants can induce GAL1 to approximately 40% of wild-type levels (E. Larschan and F. Winston, unpublished results). This result is consistent with evidence that several other factors also play roles in Gal4-mediated activation, including the general factors TATA-binding protein (TBP) and TFIIB (2, 3, 33, 38, 43, 64), Swi/Snf (61), Cti6 (47), Mediator (29, 31, 38), and Srb8-Srb11 (1, 6, 25, 30, 39). To learn more about factors involved in Gal4-mediated activation and their possible relationship to the role of SAGA, we performed a selection for suppressors of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype and identified eight complementation groups. These studies identified one group as the SRB9 gene and led us to analyze the requirement for Srb9 in GAL1 activation.

Srb9 is part of the Srb8-Srb11 complex, which has been shown to be involved in many aspects of transcription in vivo (reviewed in reference 13). Although this complex is physically associated with Mediator, it is both biochemically and genetically separable from the core Mediator (11, 13, 39). Phenotypic analysis has shown that srb8Δ-srb11Δ mutants possess many common phenotypes, including slow growth on galactose-containing medium and flocculence (6, 30, 39). Transcriptional studies have demonstrated that Srb8-Srb11 plays both positive and negative roles in transcription (13), affecting genes involved in carbon metabolism (30, 39, 56), stationary-phase entry (15), and the nitrogen starvation pathway (46). Srb10, a member of Srb8-Srb11, is a protein kinase that shares homology with cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), particularly mammalian CDK8 (reviewed in reference 44). One putative role for Srb10 in transcription was suggested by the demonstration that it can phosphorylate the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II on its carboxy-terminal domain on serine 2 and serine 5 in vitro (11, 30, 39). In vivo targets of the Srb10 kinase include the activators Gcn4 (17), Msn2 (17), Ste12 (46), Gal4 (25), and the Mediator component Med2 (22). Furthermore, in vitro transcription experiments have suggested both positive and negative roles for Srb10 (23, 40). A mutant of Srb10 that lacks kinase activity shares phenotypes with srb8Δ, srb9Δ, srb10Δ, and srb11Δ mutants, indicating that Srb10 kinase activity is required for Srb8-Srb11 function (39).

To further understand the role of Srb8-Srb11 and SAGA during Gal4 activation, we examined the binding of Srb9 to the Gal4-activated GAL1 promoter by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Our results suggest that Srb8-Srb11 associates with the GAL1 promoter in a SAGA-dependent fashion. Furthermore, the association is dependent on the SAGA component Spt3, but not Gcn5. We also show that Srb10 kinase activity is required for activation of GAL1 and the association of TBP with the GAL1 TATA element, consistent with previous results indicating that Srb10 kinase activity stimulates activity of reporter genes fused to the GAL1 promoter (30, 39). In contrast to SAGA, Srb8-Srb11 requires TBP binding for its association with the GAL1 promoter, indicating that these factors mutually stabilize each other at the GAL1 promoter. Taken together, these studies expand our understanding of the steps required for Gal4 activation of transcription initiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and plasmids.

All S. cerevisiae strains used in this study (Table 1) are congenic to FY2, an S288C derivative (62). To avoid obtaining gal80 mutations in the selection for suppressors of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype, the GAL80 gene was duplicated. To create strains that contain two copies of GAL80, the integrating plasmid pEL17, containing GAL80, was linearized at the unique StuI site in URA3 and used to transform strain FY2324. Southern blot analysis was conducted to assure correct integration of a single copy of the plasmid at ura3-52. One of the Ura+ transformants was used to generate strains FY2322 and FY2323 by crosses. The srb10-3 mutant strain (FY2347) was constructed by a two-step gene replacement with the integrating plasmid pEL22. Candidates were tested for Gal− and flocculence phenotypes, and the correct integration event was confirmed by sequencing. One-step gene replacement was used to construct the srb8Δ, srb9Δ, and srb11Δ strains (FY2346, FY2345, and FY2350) using the KANMX gene (5). The srb10Δ strain FY2340 was a gift from Grant Hartzog. The SRB9-13xMyc strain was constructed using a one-step integration of the 13xMyc-KANMX construct (41). This epitope-tagged version of Srb9 is functional based on testing the following phenotypes exhibited by srb9Δ: (i) Gal−, (ii) flocculence, and (iii) suppression of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype. Standard protocols for transformation and tetrad analysis were used for strain constructions (53).

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains

| Name | Genotype |

|---|---|

| FY1976 | MATα his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY1977 | MATα SPT20-3xHA his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2083 | MATasnf2Δ::LEU2 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 his3Δ200 met15Δ0 |

| FY2322 | MATaspt20Δ200::ARG4 [ura3-52 GAL80 URA3] his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 |

| FY2323 | MATα spt20Δ200::ARG4 [ura3-52 GAL80 URA3] his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2324 | MATaspt20Δ200::ARG4 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3-52 |

| FY2325 | MATα spt20Δ200::ARG4 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 |

| FY2326 | MATα SPT20-3xHA SRB9-13xMyc::KANMX his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2327 | MATα SRB9-13xMyc::KANMX SPT20-3xHA srb10-3 his4-917δ lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2328 | MATaSRB9-13xMyc::KANMX gal1Δ::TRP1 trp1Δ63 ura3 lys2-173R2 arg4-12 |

| FY2329 | MATα SRB9-13xMyc::KANMX spt20Δ100::URA3 ura3 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ0 |

| FY2330 | MATaSRB9-13xMyc::KANMX lys2-173R2 his4-917δ ura3-52 |

| FY2331 | MATaSRB9-13xMyc::KANMX gcn5Δ::HIS3 lys2-173R2 his3Δ200 his-917δ ura3-52 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2332 | MATaSpt3-3xHA srb9Δ::KANMX lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ1 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2333 | MATα Spt3-3xHA lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ1 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2334 | MATaSRB9-13xMyc::KANMX SPT20-3xHA spt15-21 lys2-173R2 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2335 | MATaSPT20-3xHA srb9Δ::KANMX lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2336 | MATasrb9-31 spt20Δ200::ARG4 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3-52 |

| FY2337 | MATα srb9Δ::KANMX spt20Δ100::URA3 lys2-173R2 his4-917δ leu2Δ0 ura3-52 trp1Δ63 |

| FY2338 | MATahda1Δ::KANMX ura3-52 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2339 | MATaspt20Δ200::ARG4 srb8Δ::KANMX ura3Δ0 lys2-173R2 trp1Δ63 met15Δ0 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2340 | MATα srb10Δ::TRP1 spt20Δ::ARG4 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 leu2Δ1 his4-917δ lys173R2 |

| FY2341 | MATα srb10-3 spt20Δ100::URA3 ura3Δ0 leu2Δ0 lys2-173R2 |

| FY2342 | MATα snf2Δ::LEU2 srb9-31 his4-917δ lys173R2 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 |

| FY2343 | MATaspt20Δ200::ARG4 srb11Δ::KANMX his4-917δ lys173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3-52 |

| FY2344 | MATα gal11Δ::TRP1 srb9-31 his4::Ty912-lacZ ura3 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 |

| FY2345 | MATα srb9Δ::KANMX trp1Δ63 leu2Δ1 ura3-52 his4-917δ lys173R2 |

| FY2346 | MATasrb8Δ::KANMX ura3-52 lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 his4-917δ lys173R2 |

| FY2347 | MATα srb10-3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2348 | MATα srb9-31 3 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ0 |

| FY2349 | MATα hda1Δ::KANMX spt20Δ100::URA3 leu2Δ0 his3Δ200 ura3-52 |

| FY2350 | MATα srb11Δ::KANMX SPT20-3xHA his4-917δ lys2-173R2 leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| FY2351 | MATα srb10Δ::TRP1 trp1Δ63 ura3-52 lys2-173R2 |

| L1093 | MATanhp10Δ::KANMX his3Δ1 leu2Δ1 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 |

| L1094 | MATα nhp10Δ::KANMX spt20Δ200::ARG4 met15Δ0 his4-917δ lys2-173R2 ura3-52 leu2Δ0 |

Rich (yeast extract-peptone-dextrose [YPD]), minimal (synthetic dextrose), and sporulation media were prepared as described previously (53). Yeast extract-peptone-galactose (YPgal) medium contains 2% galactose and antimycin A (1 μg/ml), and yeast extract-peptone-raffinose (YPraf) medium contains 2% raffinose. YPD-caffeine (YPcaf) medium contains 15 mM caffeine, and SD-Ino media is minimal (synthetic dextrose) media that lacks inositol (24).

Plasmid constructions used standard techniques (4). pEL17 contains the GAL80 gene on a 2.4-kb MunI/XhoI fragment from pGP15Δ (49), cloned into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of pRS406 (55). pEL22 contains a 5-kb ClaI/BamHI fragment of RY7099 containing the srb10-D304A gene (39) cloned into pRS406. The SGP4 plasmid was previously described and contains three consensus Gal4-binding sites within pRS416 (9).

Isolation and genetic characterization of spt20Δ Gal+ suppressor mutants.

To select for suppressors of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype, 50 independent cultures (each) of FY2322 and FY2323 were grown to saturation in YPD. Cells were washed two times in sterile water, and then 5 × 106 cells from each of the 100 independent cultures were spread on YPgal plates containing 1 μg of antimycin A/ml. Twenty-five plates for each strain were irradiated with UV light (300 ergs/mm2) and incubated at 30°C for 4 days. The remaining 50 plates did not receive UV treatment and were also incubated for 4 days to select for spontaneous mutants. Plates subjected to UV mutagenesis contained an average of 35 colonies per plate; plates that contained spontaneous mutants had an average of 7 colonies per plate. The stimulation in the mutant frequency by the UV treatment suggests that most of the UV-induced mutants from a single culture are likely independent. One hundred independent mutants from UV treated plates (two colonies from each of 50 plates) and 100 spontaneous mutants (two colonies from each of 50 plates) were single-colony purified and retested for suppression of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype. Gal+ suppression phenotypes were all of similar strength, with all suppressor mutants able to grow on YPgal medium 3 days after replica plating. All mutant strains were also tested for suppression of additional spt20Δ phenotypes, including the Spt phenotype, and failure to grow on YPcaf and SD-Ino media. For parent strains and every mutant strain tested, the extra copy of the GAL80 gene at the URA3 locus was lost by growth on medium containing 5-fluoroorotic acid, and all phenotypes were retested. All phenotypes were similar to those present in strains with two copies of GAL80, except that all strains grew 1 day faster on YPgal medium.

To test for dominance, all mutant strains were mated to FY2325 or FY2324, and the diploids were tested for their Gal phenotype. To perform complementation tests, a subset of MATa mutants was mated by all of the MATα mutants. Iterative rounds of complementation were conducted until 146 mutants were placed into eight complementation groups. For at least two members of each complementation group, 2:2 segregation of the Gal+ suppression phenotype was demonstrated by tetrad analysis in backcrosses to either the FY2325 or FY2324 parent strain.

Cloning three of the suppressor genes.

The genes corresponding to the group C and group H complementation groups were cloned with a genomic library (52). Group C was cloned by complementation of the weak Gal− phenotype in an SPT20+ background and was identified as SRB9. The mutation was designated srb9-31, but is hereafter referred to as srb9sup. Tetrad analysis in several crosses demonstrated that the two phenotypes conferred by srb9sup, suppression of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype and a Gal− phenotype in SPT20+ strains, are tightly linked to the SRB9 gene. Group H was cloned by complementation of the suppression of the caffeine-sensitive phenotype in the spt20Δ group H double mutant. The complementing plasmids suggested that the mutation was near the centromere of chromosome IV. DNA sequence analysis identified an amber mutation in codon 30 of the NHP10 open reading frame. Subsequent complementation, linkage analysis, and the phenotype of the spt20Δ nhp10Δ double mutant confirmed the identity of the mutation. Group D was identified as HDA1 by linkage analysis. The group D mutation was initially mapped to 7.6 centimorgans from its centromere, relative to trp1Δ63. Subsequently, linkage was demonstrated with centromere XIV, and candidate genes in the adjacent genomic loci were sequenced. A mutation in the HDA1 gene was identified that causes an R89I change in a highly conserved residue. Many attempts were made to clone the genes corresponding to the other five complementation groups by complementation of the Gal+ phenotype. However, for reasons not understood, there was a high background of unstable Gal− colonies among transformants that did not allow us to identify correct clones.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis.

RNA isolation and Northern analysis were performed as previously described (4, 58). Cells were grown at 30°C to a density of 1 × 107 to 2 × 107 cells per ml in YPraf, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min at a final concentration of 2%. Probes used for the GAL1 mRNAs were as previously described (18).

ChIP.

ChIP experiments were performed as previously described (32). Cells were grown at 30°C to a density of 1 × 107 to 2 ×107 cells per ml in YPraf, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min at a final concentration of 2%. For all ChIP experiments, Western blot analayses were conducted to assure that equal levels of immunoprecipitated proteins were present in wild-type and mutant strains. The following antibodies were used for ChIP: (i) HA (12CA5), (ii) TBP (provided by S. Buratowski), (iii) Rox3 (provided by R. Kornberg), (iv) Myc (A14; Santa Cruz), and (v) Ada1 (26). GAL1 upstream activation sequence (UAS) primers produce a PCR product that spans −536 to −276 relative to ATG and the GAL1 TATA primers produce a PCR product that extends from −190 to + 54 relative to the GAL1 ATG. Primer sequences are available upon request.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of suppressors of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype.

Before conducting a selection for mutants that bypass the requirement for SAGA during Gal4 activation, we examined whether mutations that impair two known repressors of Gal4-activated transcription, Gal80 and Tup1, can bypass the requirement for SAGA (20, 60). Therefore, we constructed spt20Δ gal80Δ and spt20Δ tup1Δ double mutants. Our results show that the gal80Δ mutation but not the tup1Δ mutation can suppress the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype (data not shown). Therefore, to avoid isolating gal80 mutations in our selection for spt20Δ suppressors, we integrated a second copy of the GAL80 gene at the URA3 locus (Materials and Methods).

We isolated 146 recessive spt20Δ Gal+ suppressors and placed them into eight complementation groups, designated groups A to H (Table 2). Eight dominant mutants were also obtained that have not been further characterized. Members of five complementation groups (groups B, C, F, G, and H) also suppress the caffeine sensitivity of the spt20Δ mutant. Group C, which contains only one member, suppresses the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype, caffeine sensitivity, and failure to grow in the absence of inositol. The single group C mutant also exhibits a very weak Gal− phenotype in a wild-type SPT20+ background that will be discussed below.

TABLE 2.

Complementation groups of spt20Δ Gal+ suppressor mutants

| Group | No. of isolates | Phenotypes in spt20Δ backgrounda | Phenotype in SPT20+ background | Identity of gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 34 | Gal+ | None | |

| B | 9 | Gal+ Cafr | None | |

| C | 1 | Gal+ Cafr Ino+ | Gal− | SRB9 |

| D | 40 | Gal+ | None | HDA1 |

| E | 29 | Gal+ | None | |

| F | 15 | Gal+ Cafr | None | |

| G | 4 | Gal+ Cafr | None | |

| H | 14 | Gal+ Cafr | None | NHP10 |

The phenotypes of suppressor mutants in each complementation group are classified as follows: (i) Gal+, if they allow the spt20Δ mutant to grow on medium containing galactose as a carbon source; (ii) Cafr, if they suppress the failure of the spt20Δ mutant to grow on medium containing the drug caffeine; and (iii) Ino+, if they suppress the failure of the spt20Δ mutant to grow in the absence of inositol.

Three of the genes, corresponding to groups C, D, and H, were identified by cloning and linkage approaches (Materials and Methods). These three genes are (i) SRB9, encoding a component of Srb8-Srb11, which is associated with Mediator (56); (ii) HDA1, encoding a histone deacetylase (14); and (iii) NHP10, encoding an HMG box protein (42). Because Srb9 is part of Srb8-Srb11, we tested the remaining complementation groups to determine if they contain srb8, srb10, or srb11 mutants. Based on both plasmid and diploid complementation tests, none of them have mutations in these three genes.

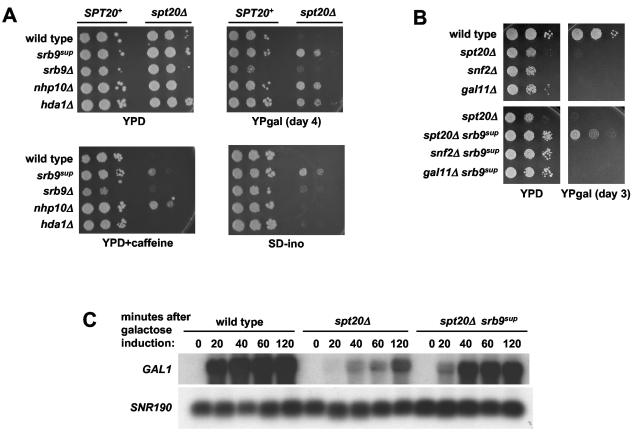

For SRB9, HDA1, and NHP10, we wanted to test if suppression is caused by loss of function. Therefore, we constructed double mutants that contain spt20Δ combined with deletions of each of these three genes and analyzed their Gal phenotypes. The phenotypes of the nhp10 and hda1 suppressor alleles are identical to those of nhp10Δ and hda1Δ mutations, strongly suggesting that suppression of spt20Δ is due to loss of function (Fig. 1A and data not shown). However, the srb9 suppressor allele, srb9sup, differs significantly from srb9Δ. First, in contrast to srb9sup, srb9Δ suppresses the Gal−, Ino−, and caffeine sensitivity phenotypes of the spt20Δ mutant extremely weakly, detectable only after prolonged growth (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Second, srb9Δ causes a much stronger Gal− phenotype than srb9sup in an SPT20 wild-type background (described below).

FIG. 1.

(A) Phenotypes of suppressors of the spt20Δ Gal− phenotype. Ten-fold serial dilutions of the indicated yeast strains were spotted on medium containing glucose (YPD), galactose (YPgal), caffeine (YPcaf), and lacking inositol (SD-Ino). The most concentrated spot contains cells from a culture at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells/ml. The srb9Δ mutants cause a weak Ino− phenotype. (B) The srb9sup allele does not suppress the Gal− phenotypes of the gal11Δ and snf2Δ mutants. Ten-fold serial dilutions of the indicated yeast strains were spotted on medium containing glucose or galactose as described for panel A. (C) The srb9sup allele partially bypasses the requirement for Spt20 in GAL1 transcription. Yeast strains were grown in YPraf medium and induced with galactose for 20, 40, 60, and 120 min. Samples were removed for RNA extraction and Northern analysis at each time point. SNR190 served as the loading control.

To further characterize suppression by srb9sup, we tested whether srb9sup could suppress the Gal− phenotype of several coactivator mutants. First, we examined whether it could suppress the Gal− phenotype caused by spt7Δ, which like spt20Δ abolishes SAGA function. The srb9sup spt7Δ double mutant is Gal+ (data not shown), demonstrating that suppression of SAGA defects by srb9sup is not specific for spt20Δ. Second, we tested for suppression of gal11Δ, which impairs Mediator function (28), and snf2Δ, which abolishes Swi/Snf function (reviewed in reference 45). Our results show that the srb9sup mutation does not suppress the Gal− phenotype caused by either deletion (Fig. 1B). Therefore, among three coactivator complexes required for transcription of GAL genes (SAGA, Mediator, and Swi/Snf), srb9sup specifically bypasses the requirement for SAGA.

To determine whether srb9sup suppresses the spt20Δ defect at the level of GAL1 transcription and TBP binding, we performed Northern hybridization analysis and ChIP experiments. Our Northern hybridization results indicate that srb9sup suppresses the GAL1 transcriptional defect in the spt20Δ mutant three- to fivefold, depending on the time after induction (Fig. 1C). TBP ChIP experiments indicate that there is a highly reproducible, modest increase in TBP binding in the spt20Δ srb9sup double mutant compared to that of the spt20Δ single mutant alone. In these ChIP experiments, we obtained the following levels of enrichment for TBP binding to the GAL1 TATA: spt20Δ, 1.2 ± 0.2; spt20Δ srb9sup, 2.0 ± 0.3; wild type, 11.8 ± 1.9. We also attempted to perform ChIP analysis of Srb9sup with wild-type and spt20Δ strains; however, phenotypic analysis demonstrated that an epitope tag at either end of Srb9sup abolished its suppression phenotype (data not shown). Overall, our Northern hybridization and ChIP data indicate that there is significant rescue of the transcriptional defects caused by the loss of SAGA in the spt20Δ srb9sup double mutant at the level of transcription and TBP binding.

The Srb8-Srb11 complex is required for Gal4-activated transcription.

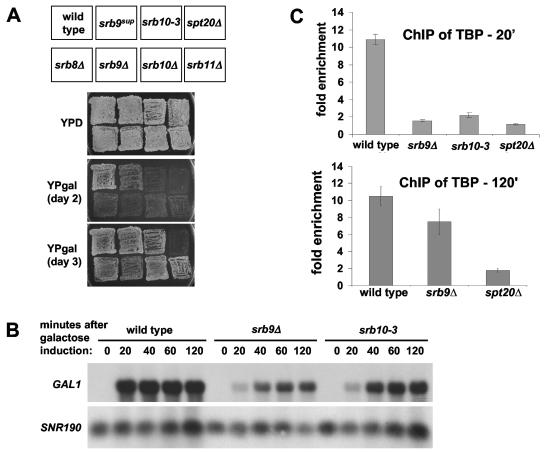

Given the strong Gal− phenotype caused by srb9Δ, we focused the remainder of our experiments on the role of Srb8-Srb11 in Gal4-mediated activation at GAL1. Previous genetic analysis suggested that the four members of Srb8-Srb11 are similarly required in transcriptional regulation (13). Therefore, we compared the Gal− phenotypes of srb8Δ, srb9Δ, srb10Δ, and srb11Δ mutants. We also included srb10-3, a mutant that abolishes the kinase activity of Srb10 (39). Our results show that the srb8Δ-srb11Δ mutants and srb10-3 mutant have strong Gal− phenotypes (Fig. 2A). These phenotypes are significantly more severe than the srb9sup mutant but less severe than an spt20Δ mutant. These results suggest that Srb8-Srb11 has a positive role in Gal4 activation in a wild-type strain, consistent with previous genetic results indicating that Srb8-Srb11 is required for GAL gene expression (6, 30, 39).

FIG. 2.

(A) The srb8Δ-srb11Δ mutants and the srb10-3 mutant all have Gal− phenotypes. Indicated strains were patched onto YPD medium and replica plated to YPD and YPgal plates. Photographs were taken on days 2 and 3 after replica plating to show that the srb8Δ-srb11Δ mutants and the srb10-3 mutants have Gal− phenotypes (day 2), but these phenotypes are weaker than that observed with an spt20Δ strain (day 3). (B) Srb9 protein and Srb10 kinase activity are important for transcription of the GAL1 gene. Yeast strains were grown in YPraf medium and induced with galactose for 20, 40, 60, and 120 min. Samples were removed for RNA extraction and Northern blotting at each time point. SNR190 served as the loading control. (C) The Srb9 protein and Srb10 kinase activity are important for TBP binding to the GAL1 TATA box. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown in medium containing raffinose, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min (top) or 120 min (bottom) prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. All ChIP experiments have been quantified as the ratio of the percentage of immunoprecipitation DNA of the sample primer set (e.g., GAL1 TATA) compared to the percentage of immunoprecipitation of a control primer set that amplifies a region on chromosome V. Each data point represents the mean and standard error of at least three independent experiments.

To test if the Gal− phenotype is caused by defects in transcription initiation and TBP binding, we conducted Northern hybridization and TBP ChIP analyses of srb9Δ and srb10-3 mutants, examining the GAL1 gene. Our results show that both srb9Δ and srb10-3 mutants have severe decreases in GAL1 mRNA levels when measured over 120 min after galactose induction (Fig. 2B). ChIP experiments also show a defect in TBP binding to the GAL1 TATA box early after induction (20 min) but not late after induction (120 min) (Fig. 2C). These defects are weaker than those exhibited by an spt20Δ mutant (Fig. 2C), correlating with the weaker Gal− phenotype in an srb9Δ mutant (Fig. 2A). Gal4 binding is largely unaffected in an srb9Δ mutant (data not shown), as was observed for an spt20Δ mutant (18). These data establish that Srb8-Srb11 functions positively in Gal4-activated transcription subsequent to Gal4 binding and is important for TBP binding. Furthermore, Srb10 kinase activity is important for these functions at GAL1, although its target remains unidentified.

One report suggests that phosphorylation of Gal4 by Srb10 activates transcription (25). However, when Gal4 phosphorylation site mutant strains were tested, they failed to exhibit a Gal− phenotype (data not shown). Therefore, in our strain background, the Gal− phenotype caused by loss of Srb8-Srb11 is not via a defect in Gal4 phosphorylation.

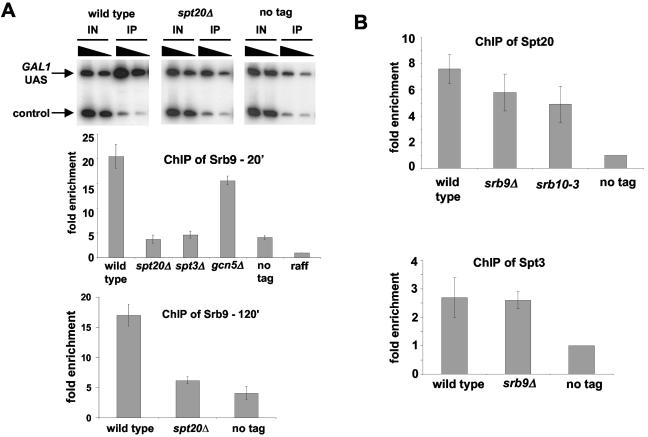

Association of Srb8-Srb11 with the GAL1 UAS is dependent on Spt3 and TBP.

To investigate whether Srb8-Srb11 functions directly to activate GAL1 transcription, we conducted ChIP experiments. These were done by assaying whether Srb9 is physically associated with the GAL1 UAS, using an epitope-tagged, functional version of Srb9 (Srb9-13xMyc). Our results show that Srb9 is indeed associated with the GAL1 UAS upon galactose induction (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

(A) Srb9 associates with the GAL1 UAS and requires SAGA for its binding. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown to mid-log phase in medium containing raffinose, followed by the addition of galactose, for 20 min (middle) or 120 min (bottom) prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. An anti-Myc antibody that recognizes the Myc epitope on Srb9-13xMyc was used for immunoprecipitation. As a control, a strain lacking the Srb9-13xMyc-tagged protein was used (no tag). Shown is an example of the radioactive PCRs for Srb9 ChIP. The mean and standard error of at least three independent experiments are shown in the bar graph. The triangles above the bands indicate twofold differences in the level of input chromatin in the reaction, to ensure that the PCR was in the linear range. (B) Spt20 and Spt3 can bind to the GAL1 UAS largely independently of Srb9. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown in YPraf medium, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. An antibody that recognizes the hemagglutinin epitope on Spt20 and Spt3 used for immunoprecipitation. The mean and standard error of at least three experiments are shown.

To test if this association is dependent upon SAGA, we performed ChIP experiments with three SAGA mutants (spt20Δ, spt3Δ, and gcn5Δ) previously characterized for their effect on Gal4 activation (9, 18, 32). Spt20 is required for SAGA integrity, affecting the association of most SAGA components, while Gcn5 and Spt3 are required for only a subset of SAGA functions (21, 57, 63). Our results show that Srb9 association at GAL1 is greatly impaired in the spt20Δ and spt3Δ mutants but not significantly reduced in a gcn5Δ strain (Fig. 3A). Even at 120 min after induction, Srb9 recruitment is significantly impaired in the spt20Δ mutant (Fig. 3A, bottom). These results correlate well with previous results showing that Spt20 and Spt3 are important for GAL1 transcription, while Gcn5 plays a more minor role (9, 18). Thus, Srb9 requires the Spt3 and Spt20 SAGA components for its association with the GAL1 UAS. Unlike Spt20, Spt3 is not required for recruitment of SAGA to the promoter, and therefore our data suggest that Spt3 may have a specific role in Srb8-Srb11 recruitment.

To test whether SAGA binding requires Srb8-Srb11, we conducted ChIP assays of Spt20 and Spt3 of SAGA in wild-type, srb9Δ, and srb10-3 strains. Our results (Fig. 3B) show that Srb9 and Srb10 kinase activity are not strongly required for the association of SAGA with the GAL1 promoter. Thus, SAGA association at the GAL1 UAS is largely independent of Srb8-Srb11. These results, then, establish a dependency pathway at GAL1: SAGA association depends upon the Gal4 activation domain (9, 32), and Srb8-Srb11 association depends upon Spt3.

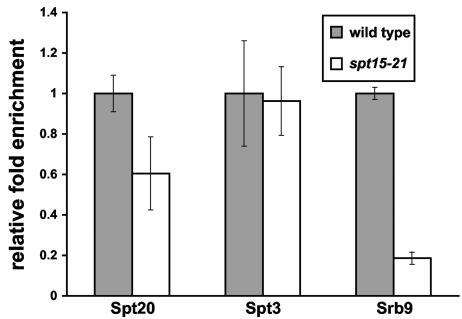

Previous studies suggested that SAGA binding to the GAL1 promoter during activation is independent of TBP binding (9, 12, 32). Therefore, we examined whether the same is true for Srb8-Srb11. To do this, we measured Srb9 association with GAL1 in an spt15-21 mutant, which encodes TBP-G174E, a TBP mutation that fails to bind to the GAL1 TATA box (32). Surprisingly, the association of Srb9 with GAL1 is severely impaired in the absence of detectable TBP binding (Fig. 4). Therefore, the binding of Srb8-Srb11 and TBP are mutually dependent. As previously shown, SAGA is still able to bind at GAL1 under these conditions (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Srb9 association with the GAL1 UAS requires TBP binding. A ChIP assay was conducted on strains grown in YPraf medium, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. An antibody that recognizes the hemagglutinin epitope on Spt20 and Spt3 in respective strains was used for immunoprecipitation, and a Myc antibody was used to immunoprecipitate the Srb9-13xMyc protein. The data shown are the relative fold enrichments, where the value for the wild-type strain has been set to 1. The actual fold enrichment values for Srb9 ChIP are 20.5 ± 6.5 for the wild type and 3.8 ± 0.7 for spt15-21. For the Spt3 ChIP, the values are 2.7 ± 1.2 for the wild type and 2.6 ± 0.8 for spt15-21. For the Spt20 ChIP, the values are 7.6 ± 1.2 for the wild type and 4.6 ± 2.4 for spt15-21.

To test whether Spt3 and Srb9 function independently or in the same pathway in GAL1 activation, we conducted Northern analysis of the srb9Δ spt3Δ double mutant and the srb9Δ and spt3Δ single mutants. Our Northern results (data not shown) indicate that there is no additional transcription defect in the srb9Δ spt3Δ double mutant compared to the srb9Δ and spt3Δ single mutants. These data correlate with the ChIP analysis that suggests that Spt3 is required for Srb8-Srb11 association with the promoter (Fig. 3A). Thus, our genetic studies, Northern data, and ChIP analysis all suggest a model in which Srb8-Srb11 acts in the same functional pathway as SAGA during Gal4 activation.

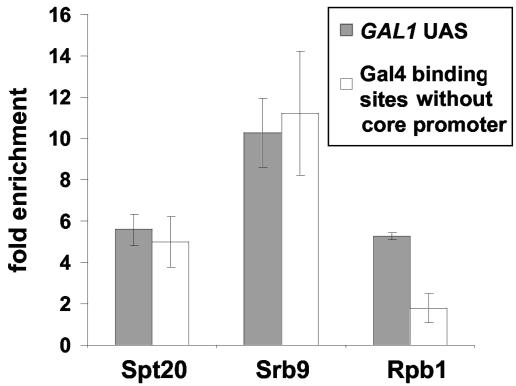

The mutual dependence of TBP and Srb8-Srb11 association with the GAL1 promoter suggested that Srb8-Srb11 association might be dependent upon the formation of a preinitiation complex. Therefore, we tested whether Srb8-Srb11 can bind to a promoter independently of RNA polymerase II (Pol II). To do this, we used a previously described plasmid that contains three consensus Gal4-binding sites but no other promoter elements. In agreement with previous studies (9), our results suggest that SAGA can associate with these isolated Gal4-binding sites, while RNA Pol II cannot. Our results also show that Srb9 associates with the Gal4-binding sites on this plasmid (Fig. 5), suggesting that the association of Srb8-Srb11 with Gal4-binding sites can occur independently of RNA Pol II.

FIG. 5.

SAGA and Srb9 associate with Gal4-binding sites in the absence of RNA Pol II. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown in YPraf medium, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. Antibodies that recognize the hemagglutinin epitope on Spt20-3xHA, the Myc epitope on Srb9-13xMyc, and the 8WG16 anti-Rbp1 antibody were used for immunoprecipitation. Binding of factors to the isolated Gal4-binding sites is shown in white bars, and binding to the endogenous GAL1 UAS is shown in gray bars. The mean and standard error are shown for at least three experiments.

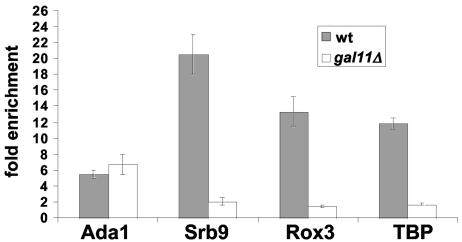

The Mediator core complex is required for association of Srb8-Srb11 but not of SAGA.

Previous studies have established that Srb8-Srb11 is associated with the core Mediator complex (11, 39) and that Mediator can be recruited to the GAL1 promoter independently of RNA Pol II and general transcription factors (31). Other studies have tested whether SAGA is required for the association of the core Mediator with the GAL1 UAS (10, 12), with different results (see Discussion). Therefore, we examined the relationship between Srb8-Srb11 and core Mediator at GAL1 by ChIP assays. First, we tested whether Mediator is required for the association of Srb8-Srb11 at GAL1 by measuring Srb9 association in wild-type and gal11Δ strains. While the Mediator complex is largely intact in a gal11Δ strain, it cannot be recruited to the GAL1 promoter (35, 48). Our data are consistent with these results and show that the Rox3 core Mediator component fails to associate with the GAL1 promoter in the gal11Δ strain (Fig. 6). Furthermore, Srb9 association is severely reduced in the gal11Δ mutant (Fig. 6). Consistent with these data, the level of TBP association is also greatly reduced, as previously demonstrated (12). In contrast, the level of SAGA association is unaffected (Fig. 6). Thus, core Mediator is required for the association of Srb8-Srb11 and TBP but not of SAGA.

FIG. 6.

The Gal11 core Mediator component is not required for the association of SAGA but is required for the association of Srb8-Srb11, the Rox3 core Mediator component, and TBP. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown in YPraf medium, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. Antibodies that recognize the Ada1 SAGA component, the Myc epitope on Srb9-13xMyc, TBP, and Rox3 were used for ChIP. Data shown represent the mean and standard error of at least three experiments.

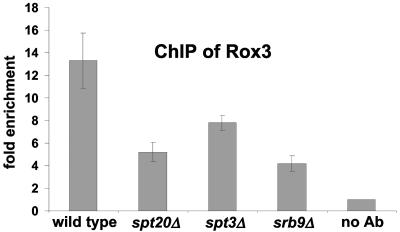

To test whether Mediator association at GAL1 is dependent upon Srb8-Srb11 and SAGA, we conducted ChIP experiments measuring Rox3 of Mediator in srb9Δ, spt3Δ, and spt20Δ mutants. Our results (Fig. 7) show that, although the level of Rox3 association is reduced in these mutants, there is still significant binding at GAL1. Therefore, core Mediator can still associate, albeit to a limited extent, in the absence of SAGA or Srb8-Srb11. The reduced level of association may reflect slower kinetics in the spt20Δ mutant, as recently demonstrated by Lemieux and Gaudreau (36). In contrast to core Mediator, the association of Srb8-Srb11 at GAL1 is completely dependent upon SAGA (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the requirements for Mediator and Srb8-Srb11 association are different.

FIG. 7.

Rox3 binding to the GAL1 UAS is partially dependent on SAGA and Srb8-Srb11. A ChIP assay was conducted with strains grown in medium containing raffinose, followed by the addition of galactose for 20 min prior to cross-linking with formaldehyde. Antibodies that recognize the Rox3 protein were used for the ChIP assay. Data represent the mean and standard error of at least three experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our results have provided strong evidence for a direct role for Srb8-Srb11 in Gal4-activated transcription. Previous results, using genetic tests and GAL1 promoter fusions to reporter genes, had suggested that srb8Δ-srb11Δ mutants have defects in GAL1 transcription (6, 30, 39). Our results have extended these conclusions in several ways. First, in mutants lacking Srb8-Srb11, the level of GAL1 mRNA is greatly reduced. Second, ChIP experiments have shown that Srb8-Srb11 is recruited to the GAL1 UAS under activating conditions, suggesting that Srb8-Srb11 plays a direct role in Gal4-mediated activation. Third, the physical association of Srb8-Srb11 at the GAL1 promoter is dependent upon several factors, including SAGA, core Mediator, and TBP. Our data also suggest that the association of Srb8-Srb11 is not dependent upon RNA Pol II. Fourth, Srb8-Srb11 is required for a normal level of association of TBP at the GAL1 promoter. Fifth, the requirements for the physical association of Srb8-Srb11 and core Mediator are distinct. Taken together, these results suggest a model in which Srb8-Srb11 plays a critical role in Gal4-mediated activation via recruitment or stabilization of TBP. Furthermore, this role requires interactions with several other factors known to play roles in Gal4-mediated activation.

Our results are consistent with a model in which a significant and necessary role of core Mediator in Gal4-mediated activation is to help recruit the Srb10 kinase activity. Our analysis of an Srb10 mutant that lacks kinase activity has demonstrated that it has the same phenotype as null mutations in SRB8-SRB11 with respect to its Gal− phenotype, reduced levels of GAL1 mRNA, and defects in TBP recruitment. Since loss of Srb8-Srb11 results in only partial impairment of core Mediator recruitment while causing a severe defect in TBP recruitment, Srb8-Srb11 may play a more significant direct role than core Mediator in Gal4-mediated activation. The strong defect in TBP recruitment to GAL1 previously shown to occur in an srb4 mutant (38) could be caused via a defect in recruitment of Srb8-Srb11. Previous evidence does suggest some direct role for core Mediator, as direct interactions between Srb4 and Gal4 (29) have been shown.

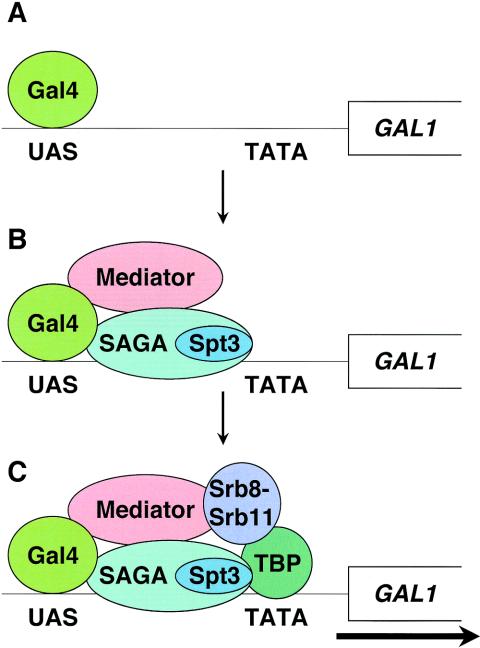

The assembly of SAGA, core Mediator, Srb8-Srb11, and TBP at the GAL1 promoter is unlikely to occur in a linear dependency pathway, as the association of Srb8-Srb11 is dependent upon all three other factors studied. With respect to SAGA, the physical association of Srb8-Srb11 at GAL1 is dependent upon Spt3 but not Gcn5. However, previous studies have shown that Spt3 is required for the association of TBP at the GAL1 promoter and have suggested direct interactions between Spt3 and TBP (9, 18, 19, 32). Therefore, the dependence of Srb8-Srb11 on Spt3 may be indirect, via the role of Spt3 in TBP recruitment. One model consistent with our data (Fig. 8) suggests multiple interactions during assembly of these factors at GAL1. In this model, Srb8-Srb11 is recruited to the promoter by its association with Mediator, TBP is recruited by Spt3, and Srb8-Srb11 and TBP are required for mutual stabilization. Recent results have suggested a mutually dependent role for Mot1 and Spt3 in recruitment to GAL1 (59).

FIG. 8.

A dependency pathway model for assembly of factors required for activation at GAL1. (A) Prior to induction, only Gal4 is bound to the GAL1 promoter. (B) Upon induction by galactose, Gal4 recruits SAGA. The recruitment of Mediator is dependent upon both SAGA and Gal4. (C) Spt3 of SAGA recruits TBP, and SAGA and Mediator recruit Srb8-Srb11. In the assembled structure, Srb8-Srb11 and TBP are mutually required for their association at the GAL1 promoter.

Our ChIP experiments suggest that core Mediator can still associate with the GAL1 promoter in the absence of SAGA, although at a lower level. The ability of Mediator to associate with the GAL1 promoter has also recently been examined in several other studies (10, 12, 16, 36). Most of these studies have also concluded that at least some Mediator association still occurs in the absence of SAGA (12, 16, 36). In contrast, one study concluded that the association of the core Mediator is very strongly dependent on SAGA (10). The reasons for the two different types of results are not understood but could be caused by ChIP analysis of different Mediator subunits or different ChIP conditions. Regardless of this particular result, all of these studies conclude that Mediator plays a significant role in Gal4-mediated activation. Our results suggest that a critical aspect of this role is via the association of core Mediator with Srb8-Srb11.

Several candidates exist for the Srb10 substrate at the GAL1 promoter, including RNA Pol II (11, 30, 39), TBP, and any other initiation factors at the GAL1 UAS. Some of the known Srb10 substrates are unlikely to play a role. For example, two TFIID components, Bdf1 and Taf2, are known in vitro targets for Srb10 phosphorylation (40). However, TFIID components are unlikely to be the relevant Srb10 targets at the GAL1 promoter because TFIID is neither required for GAL1 transcription nor associated with the GAL1 promoter (8, 32, 37). Med2, a component of core Mediator, is another in vivo target of Srb10, but a Med2 mutation that cannot be phosphorylated fails to exhibit a Gal− phenotype (22). Finally, Gal4 has been shown to be a substrate for Srb10 (25) and a Gal4 mutation that cannot be phosphorylated by Srb10 was reported to exhibit 25% of wild-type normal activity (25). However, this Gal4 mutation does not cause any detectable phenotype in our strain background (data not shown). The identification of the Srb10 target in Gal4-mediated activation will provide an important advance in understanding the role of Srb8-Srb11.

We initially identified Srb9 by a selection for suppressor mutations that could bypass the loss of SAGA activity at GAL genes. The srb9 suppressor mutant that we identified causes phenotypes quite distinct from that of an srb9Δ mutant. Additional experiments are required to understand how this Srb9 mutant, Srb9sup, partially bypasses the requirement for SAGA during Gal4 activation. Perhaps the Srb9sup protein has a neomorphic function that allows it to facilitate Gal4-mediated activation, either directly or indirectly. Additional studies of this class of Srb9 mutation may elucidate additional aspects of Srb8-Srb11 function. In addition, analysis of the other seven genes identified in this selection seem likely to yield additional insights into Gal4-mediated activation.

Finally, further studies are required to determine whether the relationships between SAGA, core Mediator, Srb8-Srb11, and TBP at GAL1 also occur at other promoters. Recent genome-wide expression studies indicated that the majority of the SAGA regulated promoters also require Mediator and Srb10 kinase activity but not TFIID (7, 27). However, in contrast to the situation with Gal4, another recent study suggested that SAGA and Srb10 play a significant role in stabilizing RNA Pol II independently of TBP during activation by Gcn4 (50). Thus, the nature of the relationship between SAGA and Srb10 in transcriptional activation may differ, depending upon the transcriptional activator involved.

Acknowledgments

We thank Krista Dobi, Natalie Kuldell, and Jenny Wu for helpful comments on the manuscript. We thank Steve Buratowski for providing the TBP antisera, and James Hopper, Michael Green, Grant Hartzog, Ivan Sadowski, and Richard Young for providing plasmids and strains.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM45720 to F.W. E.L. was supported by a Genetics of Cancer and Inherited Diseases training grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansari, A. Z., S. S. Koh, Z. Zaman, C. Bongards, N. Lehming, R. A. Young, and M. Ptashne. 2002. Transcriptional activating regions target a cyclin-dependent kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14706-14709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ansari, A. Z., R. J. Reece, and M. Ptashne. 1998. A transcriptional activating region with two contrasting modes of protein interaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:13543-13548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arndt, K. M., S. Ricupero-Hovasse, and F. Winston. 1995. TBP mutants defective in activated transcription in vivo. EMBO J. 14:1490-1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1988. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates, New York, N.Y.

- 5.Baganz, F., A. Hayes, D. Marren, D. C. Gardner, and S. G. Oliver. 1997. Suitability of replacement markers for functional analysis studies in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13:1563-1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balciunas, D., and H. Ronne. 1995. Three subunits of the RNA polymerase II mediator complex are involved in glucose repression. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4421-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basehoar, A. D., S. J. Zanton, and B. F. Pugh. 2004. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell 116:699-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green. 2002. Differential requirement of SAGA components for recruitment of TATA-box-binding protein to promoters in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7365-7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhaumik, S. R., and M. R. Green. 2001. SAGA is an essential in vivo target of the yeast acidic activator Gal4p. Genes Dev. 15:1935-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhaumik, S. R., T. Raha, D. P. Aiello, and M. R. Green. 2004. In vivo target of a transcriptional activator revealed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Genes Dev. 18:333-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borggrefe, T., R. Davis, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and R. D. Kornberg. 2002. A complex of the srb8, -9, -10, and -11 transcriptional regulatory proteins from yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 277:44202-44207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryant, G. O., and M. Ptashne. 2003. Independent recruitment in vivo by Gal4 of two complexes required for transcription. Mol. Cell 11:1301-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson, M. 1997. Genetics of transcriptional regulation in yeast: connections to the RNA polymerase II CTD. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13:1-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carmen, A. A., S. E. Rundlett, and M. Grunstein. 1996. HDA1 and HDA3 are components of a yeast histone deacetylase (HDA) complex. J. Biol. Chem. 271:15837-15844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang, Y. W., S. C. Howard, Y. V. Budovskaya, J. Rine, and P. K. Herman. 2001. The rye mutants identify a role for Ssn/Srb proteins of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme during stationary phase entry in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 157:17-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng, J. X., M. Gandolfi, and M. Ptashne. 2004. Activation of the gal1 gene of yeast by pairs of ‘non-classical’ activators. Curr. Biol. 14:1675-1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chi, Y., M. J. Huddleston, X. Zhang, R. A. Young, R. S. Annan, S. A. Carr, and R. J. Deshaies. 2001. Negative regulation of Gcn4 and Msn2 transcription factors by Srb10 cyclin-dependent kinase. Genes Dev. 15:1078-1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley, A. M., C. Rougeulle, and F. Winston. 1999. The Spt components of SAGA facilitate TBP binding to a promoter at a post-activator-binding step in vivo. Genes Dev. 13:2940-2945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenmann, D. M., K. M. Arndt, S. L. Ricupero, J. W. Rooney, and F. Winston. 1992. SPT3 interacts with TFIID to allow normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 6:1319-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukasawa, T., K. Obonai, T. Segawa, and Y. Nogi. 1980. The enzymes of the galactose cluster in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. II. Purification and characterization of uridine diphosphoglucose 4-epimerase. J. Biol. Chem. 255:2705-2707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant, P. A., L. Duggan, J. Cote, S. M. Roberts, J. E. Brownell, R. Candau, R. Ohba, T. Owen-Hughes, C. D. Allis, F. Winston, S. L. Berger, and J. L. Workman. 1997. Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes Dev. 11:1640-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallberg, M., G. V. Polozkov, G.-Z. Hu, J. Beve, C. M. Gustafsson, H. Ronne, and S. Björklund. 2004. Site-specific Srb10-dependent phosphorylation of the yeast Mediator subunit Med2 regulates gene expression from the 2-μm plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:3370-3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hengartner, C. J., V. E. Myer, S. M. Liao, C. J. Wilson, S. S. Koh, and R. A. Young. 1998. Temporal regulation of RNA polymerase II by Srb10 and Kin28 cyclin-dependent kinases. Mol. Cell 2:43-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henry, S. A., T. F. Donahue, and M. R. Culbertson. 1975. Selection of spontaneous mutants by inositol starvation in yeast. Mol. Gen. Genet. 143:5-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirst, M., M. S. Kobor, N. Kuriakose, J. Greenblatt, and I. Sadowski. 1999. GAL4 is regulated by the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme-associated cyclin-dependent protein kinase SRB10/CDK8. Mol. Cell 3:673-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horiuchi, J., N. Silverman, B. Pina, G. A. Marcus, and L. Guarente. 1997. ADA1, a novel component of the ADA/GCN5 complex, has broader effects than GCN5, ADA2, or ADA3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:3220-3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huisinga, K. L., and B. F. Pugh. 2004. A genome-wide housekeeping role for TFIID and a highly regulated stress-related role for SAGA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 13:573-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim, Y. J., S. Bjorklund, Y. Li, M. H. Sayre, and R. D. Kornberg. 1994. A multiprotein mediator of transcriptional activation and its interaction with the C-terminal repeat domain of RNA polymerase II. Cell 77:599-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh, S. S., A. Z. Ansari, M. Ptashne, and R. A. Young. 1998. An activator target in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol. Cell 1:895-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuchin, S., P. Yeghiayan, and M. Carlson. 1995. Cyclin-dependent protein kinase and cyclin homologs SSN3 and SSN8 contribute to transcriptional control in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:4006-4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuras, L., T. Borggrefe, and R. D. Kornberg. 2003. Association of the Mediator complex with enhancers of active genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:13887-13891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larschan, E., and F. Winston. 2001. The S. cerevisiae SAGA complex functions in vivo as a coactivator for transcriptional activation by Gal4. Genes Dev. 15:1946-1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee, M., and K. Struhl. 1995. Mutations on the DNA-binding surface of TATA-binding protein can specifically impair the response to acidic activators in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:5461-5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, T. I., H. C. Causton, F. C. Holstege, W. C. Shen, N. Hannett, E. G. Jennings, F. Winston, M. R. Green, and R. A. Young. 2000. Redundant roles for the TFIID and SAGA complexes in global transcription. Nature 405:701-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, Y. C., J. M. Park, S. Min, S. J. Han, and Y. J. Kim. 1999. An activator binding module of yeast RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:2967-2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemieux, K., and L. Gaudreau. 2004. Targeting of Swi/Snf to the yeast GAL1 UAS(G) requires the Mediator, TAF(II)s, and RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 23:4040-4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, X. Y., S. R. Bhaumik, and M. R. Green. 2000. Distinct classes of yeast promoters revealed by differential TAF recruitment. Science 288:1242-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li, X. Y., A. Virbasius, X. Zhu, and M. R. Green. 1999. Enhancement of TBP binding by activators and general transcription factors. Nature 399:605-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao, S. M., J. Zhang, D. A. Jeffery, A. J. Koleske, C. M. Thompson, D. M. Chao, M. Viljoen, H. J. van Vuuren, and R. A. Young. 1995. A kinase-cyclin pair in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nature 374:193-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, Y., C. Kung, J. Fishburn, A. Z. Ansari, K. M. Shokat, and S. Hahn. 2004. Two cyclin-dependent kinases promote RNA polymerase II transcription and formation of the scaffold complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:1721-1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longtine, M. S., A. McKenzie III, D. J. Demarini, N. G. Shah, A. Wach, A. Brachat, P. Philippsen, and J. R. Pringle. 1998. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14:953-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu, J., R. Kobayashi, and S. J. Brill. 1996. Characterization of a high mobility group 1/2 homolog in yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 271:33678-33685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Melcher, K., and S. A. Johnston. 1995. GAL4 interacts with TATA-binding protein and coactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:2839-2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Naar, A. M., B. D. Lemon, and R. Tjian. 2001. Transcriptional coactivator complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:475-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narlikar, G. J., H. Y. Fan, and R. E. Kingston. 2002. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell 108:475-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nelson, C., S. Goto, K. Lund, W. Hung, and I. Sadowski. 2003. Srb10/Cdk8 regulates yeast filamentous growth by phosphorylating the transcription factor Ste12. Nature 421:187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papamichos-Chronakis, M., T. Petrakis, E. Ktistaki, I. Topalidou, and D. Tzamarias. 2002. Cti6, a PHD domain protein, bridges the Cyc8-Tup1 corepressor and the SAGA coactivator to overcome repression at GAL1. Mol. Cell 9:1297-1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park, J. M., H. S. Kim, S. J. Han, M. S. Hwang, Y. C. Lee, and Y. J. Kim. 2000. In vivo requirement of activator-specific binding targets of mediator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8709-8719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peng, G., and J. E. Hopper. 2000. Evidence for Gal3p's cytoplasmic location and Gal80p's dual cytoplasmic-nuclear location implicates new mechanisms for controlling Gal4p activity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:5140-5148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu, H., C. Hu, S. Yoon, K. Natarajan, M. J. Swanson, and A. G. Hinnebusch. 2004. An array of coactivators is required for optimal recruitment of TATA binding protein and RNA polymerase II by promoter-bound Gcn4p. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:4104-4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roberts, S. M., and F. Winston. 1997. Essential functional interactions of SAGA, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae complex of Spt, Ada, and Gcn5 proteins, with the Snf/Swi and Srb/mediator complexes. Genetics 147:451-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rose, M. D., and J. R. Broach. 1991. Cloning genes by complementation in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194:195-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rose, M. D., F. Winston, and P. Hieter. 1990. Methods in yeast genetics: a laboratory course manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 54.Roth, S. Y., J. M. Denu, and C. D. Allis. 2001. Histone acetyltransferase complexes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70:81-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sikorski, R. S., and P. Hieter. 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122:19-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song, W., I. Treich, N. Qian, S. Kuchin, and M. Carlson. 1996. SSN genes that affect transcriptional repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae encode SIN4, ROX3, and SRB proteins associated with RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:115-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sterner, D. E., P. A. Grant, S. M. Roberts, L. J. Duggan, R. Belotserkovskaya, L. A. Pacella, F. Winston, J. L. Workman, and S. L. Berger. 1999. Functional organization of the yeast SAGA complex: distinct components involved in structural integrity, nucleosome acetylation, and TATA-binding protein interaction. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:86-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swanson, M. S., E. A. Malone, and F. Winston. 1991. SPT5, an essential gene important for normal transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encodes an acidic nuclear protein with a carboxy-terminal repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3009-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Topalidou, I., M. Papamichos-Chronakis, G. Thireos, and D. Tzamarias. 2004. Spt3 and Mot1 cooperate in nucleosome remodeling independently of TBP recruitment. EMBO J. 23:1943-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treitel, M. A., and M. Carlson. 1995. Repression by SSN6-TUP1 is directed by MIG1, a repressor/activator protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:3132-3136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Winston, F., and M. Carlson. 1992. Yeast SNF/SWI transcriptional activators and the SPT/SIN chromatin connection. Trends Genet. 8:387-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Winston, F., C. Dollard, and S. L. Ricupero-Hovasse. 1995. Construction of a set of convenient Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that are isogenic to S288C. Yeast 11:53-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu, P. Y., and F. Winston. 2002. Analysis of Spt7 function in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae SAGA coactivator complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:5367-5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu, Y., R. J. Reece, and M. Ptashne. 1996. Quantitation of putative activator-target affinities predicts transcriptional activating potentials. EMBO J. 15:3951-3963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]