Abstract

Background:

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a disorder characterized by progressive cicatricial alopecia (CA). Its classification as a clinical variant of lichen planopilaris (LPP) or as a unique disorder is controversial. The presence of Langerhans cells within the bulge area and the sebaceous epithelium and the presence of lymphocytic infiltrate in this area in CA have led to a series of hypotheses, although limited, about their development. To our knowledge, scarce is the literature demonstrating immunoanalytical studies comparing both disorders.

Objective:

The authors sought to describe diagnostic findings, comorbidities, and immunopathological features of female patients with FFA as compared to LPP.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective single-center study included patients given the diagnosis of FFA or LPP. The LPP activity index was used to evaluate objective signs and subjective symptoms. Biopsy specimens were obtained from active, inflammatory areas of the scalp, and the inflammatory infiltrate intensity and quality were compared. Direct immunofluorescence for IgA, IgM, and IgG and immunohistochemistry to demonstrate the expression of CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68, and 2,3-dioxygenase indoleamine were performed.

Results:

Twenty female patients (10 patients with FFA and 10 patients with LPP) were included in the study. Histopathological findings evidenced reduced number of hair follicles and perifollicular fibrosis in both disorders. Immunofluorescence findings resulted positive in 50% of FFA cases and 40% of LPP cases.

Conclusion:

Although clinically different, our findings suggest that there are, to date, no histological or immunological findings that allow us to accurately separate these two forms of scarring alopecia, namely FFA and LPP.

Key words: Alopecia, comparative study, immune response, lichen planus, scar

INTRODUCTION

Alopecias can be broadly classified into noncicatricial and cicatricial forms. Pathologically, a scar constitutes the end point of reparative fibrosis with permanent destruction of the preexisting tissue. Cicatricial alopecias (CAs) address complex and chronic inflammatory diseases that lead to permanent hair loss, subdivided into primary and secondary types. Primary CA is further classified into three groups: Lymphocytic (chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, lichen planopilaris [LPP], classic pseudopelade of Brocq, central centrifugal alopecia, alopecia mucinosa, and keratosis follicularis decalvans), neutrophilic (folliculitis decalvans, dissecting folliculitis), and mixed (folliculitis keloidalis, folliculitis necrotica, and erosive pustular dermatosis). There is little knowledge on the etiology and pathogenesis of these types of alopecia. Besides, in the late phase of many CAs, a histopathologic diagnosis is difficult because the main criteria of classification cannot be accurately evaluated. In these cases, additional criteria, such as the evaluation of the perifollicular elastic sheet and the fibrosis, can be useful.[1,2]

In CAs, routine biopsy examination reveals that the affected hair follicles are involved by an intense inflammatory infiltrate, and the infiltrate composition (lymphocytic and/or neutrophilic) suggests a specific type of CA.[1] The infiltration is often observed in the upper and permanent portion of the pilosebaceous unit, where the stem cells of follicular bulge are located. The presence of Langerhans cells within the bulge area and the sebaceous epithelium and the presence of lymphocytic infiltrate in this area in CA have led to a series of hypotheses, although limited, about their development: Autoimmune-mediated CA, immune privilege breakdown leading to scarring alopecia, and bulge stem cell destruction hypothesis of scarring alopecia development.[3]

LPP presents as an isolated manifestation of lichen planus (LP) at the scalp or may be further associated with cutaneous, mucosal, or ungueal forms of LP. The condition called frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is sometimes regarded as being a clinical variant of LPP. It has been reported more often in postmenopausal Caucasian women who present progressive alopecia along the front line of hair implantation and loss of eyebrows.

Despite different clinical characteristics between FFA and LPP patients, the histopathological findings of both entities tend to be similar. Current comparative studies still diverge from the existing classification of the two entities. In some cases, studies of FFA biopsies showed less intensity of the follicular inflammation and a higher number of apoptotic cells as compared to patients with LPP. Besides, in patients with FFA, the interfollicular epidermis tends not to be affected by the inflammatory infiltrate, unlike what happens in cases of LPP.[4]

Current efforts are focused on setting new standards for the classification of CA based on hypotheses about the pathogenesis, but this is only possible if the clinical, histological, and immunological characteristics are better understood. The objectives of this study are to outline demographic data and the main clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical differences between LPP and FFA patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective study including a thorough medical history of patients with LPP or FFA. Histopathological and immunohistochemistry analyses on biopsy specimens obtained from patients of the Hair and Scalp Unit of the Dermatology Department of University of São Paulo Medical School (HC-FMUSP) were undertaken between 2009 and 2013.

The data collected from medical history included age and onset time, extent of scalp involvement, signs and symptoms of affected areas, and associated comorbidities. The LPP activity index[5] was used to evaluate objective signs (redness, scaling, and hair loss) and subjective symptoms (itching and burning).

All blocks and blades were obtained from scalp samples by biopsy with 4 mm punch with representation of the hypodermis. The specimen thus obtained was immediately divided into two, a half sent to histological analysis stained by hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid-Schiff, and Weigert's method with prior oxidation by peracetic acid. The other half of the biopsy specimen went to direct immunofluorescence (DIF). Results of DIF of samples from all twenty patients of affected sites on the scalp were compared.

A review of the histological preparations was done in a blinded manner, evaluating the presence, quality, and intensity of the following findings: Perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (IF), perifollicular fibrosis (FI), apoptosis in hair follicles (AP), infundibular dilatation (DI), lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrate at the interface between the interfollicular epidermis and the dermis (IL), and perifollicular foreign body granulomatous reaction (EC). This semiquantitative analysis of histological signs was graded in intensity from signal ±3; the negative (−), mild (1+), moderate (2+), and severe (3+).

To demonstrate the expression of Langerhans cells (CD1a) and T-cells (CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68) and 2,3-dioxygenase indoleamine (IDO) in skin specimens, immunohistochemistry was done in all biopsy specimens. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-micra paraffin-embedded samples, as described elsewhere [Table 1 displays the chosen antibody specifications, dilution]. The Novolink Polymer Detection Systems was used.

Table 1.

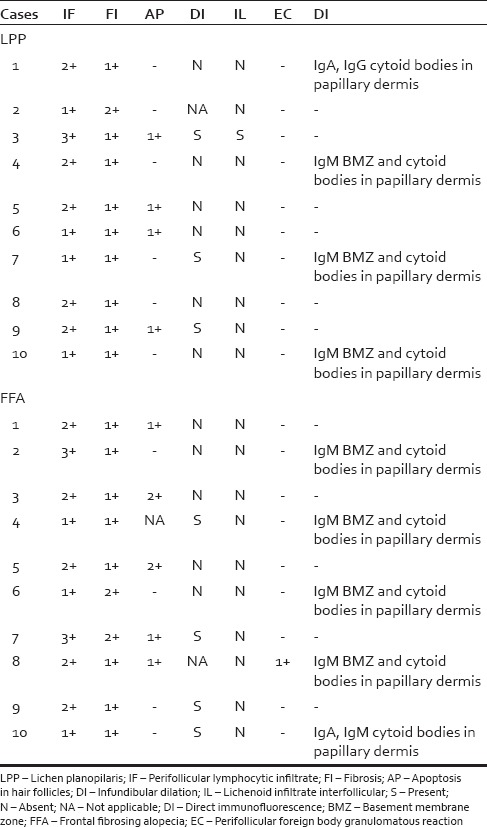

Histological and directed immunofluorescence comparative analysis of lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia

Three oil-emersion high-power fields were examined for each section without the knowledge of the diagnosis or antibody applied. The percentage of stained cells in the infiltrate was counted and expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells in the inflammatory infiltrate.

Statistical analysis of the results was performed using Student's t-test and Fisher's exact test for parametric data and G-test for the nonparametric data for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Clinical evaluation

FFA cases included seven Caucasian and three Mulatto patients and LPP cases included six Pardas and four Caucasian patients. The age of onset ranged from 42 to 67 years (average of 60 years). As for as the disease duration is concerned, it ranged from 1 to 17 years (average of 4.5 years), nine patients had more than 5 years of disease duration. Neither early menopause nor a history of hysterectomy could be elicited in any case.

Laboratory tests and clinical history revealed the following comorbidities: Hypothyroidism (30%), type 2 diabetes (20%), hypertension (20%), and nodosa poliarteritis (10%) in LPP, and hypothyroidism (20%), type 2 diabetes (10%), and hypertension (10%) in FFA patients.

As for as the involvement of the scalp is concerned, in LPP, there was a predominance of a multifocal pattern diffusely affecting the scalp in 50% of patients; conversely, FFA cases had a frontotemporal involvement in 100% of cases. Patients with LPP presented burning in 30% and rash in 30% as the main symptoms. The main signal was peripilar desquamation in 80% of LPP cases and 50% of FFA cases. Facial papules were present in four FFA patients, and the majority of patients presented mild FFA with a recession of <3 cm of the temporal hairline.

Histopathothological findings

The main histological findings included inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrates interfaced between the follicular epithelium and dermis involving the isthmus and the follicular infundibulum with lichenoides standard, perifollicular fibrosis, apoptotic keratinocytes in the outer root sheath, and destruction of the hair follicle. The comparative histological findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantity/study area of distribution of CD1a and CD3 in lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia

Direct immunofluorescence findings

DIF was performed on twenty specimens of scalp biopsies. Concerning LPP, three of the ten patients showed the presence of moderate, granulous, and continuous IgM immunofluorescence in the epidermal and follicular basement membrane zone and four had cytoid bodies in the papillary dermis of IgG, IgA, and IgM. Among patients with FFA, four showed the presence of moderate, granulous, and continuous IgM immunofluorescence in the epidermal and follicular basement membrane zone and five had cytoid bodies in the papillary dermis of IgM [Table 2].

Immunochemistry findings

The counting of CD1a- and IDO-positive cells was performed in all immune marked follicles, and the CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD68 positive count was demonstrated by reading at least three fields affected by inflammatory infiltrate. Upon completion of the staining procedure, ratios of CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68, and IDO to total areas were obtained by one observer. Where there was no inflammatory infiltrate, no count was undertaken. Analysis of immunohistochemical findings which evaluated the CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68, and IDO of the collected biopsy specimens of twenty patients (10 LPP and 10 FFA) was carried out [Table 2]. Immunohistochemical studies showed no significant differences. The histological preparations were verified by noting the presence or absence of histological criteria that show the usual performance of the inflammatory infiltrate in the two diseases. Studies of DIF and demonstration of expression of CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68, and IDO in skin specimens were also executed; we have used immunohistochemistry.

Comments

Twenty female patients (10 patients with FFA and 10 patients with LPP) were included with a mean age of 55.6 ± 6.87 years in FFA cases (range: 45–69) and 63.3 ± 8.69 years in LPP cases (range: 50–81). The average disease duration was 4.5 ± 5.8 years in FFA patients (range: 1–17). Pruritus of the scalp was the most commonly reported symptom, occurring in 3 cases (30%) of LPP and in 6 cases (60%) of FFA. Comorbidities mainly included hypothyroidism in 3 cases (30%) and type 2 diabetes in 1 case (10%) of LPP, and hypothyroidism in 1 case (10%) of FFA.

LP is a disorder of unknown etiology, sometimes referred as a “reaction pattern” belonging to the autoimmune group of conditions. It occurs worldwide but there are marked variations in its incidence and clinical manifestations. Significant involvement of the scalp is relatively infrequent – only 10 of 807 in one series. On the other hand, when considering two unusual variants of LP, the bullous or erosive form and LPP, scalp involvement occurs in over 40% of patients.[6]

LPP classically manifests as follicular plugs, hair loss in a patchy or diffuse pattern, and perifollicular violaceus erythema. In this disorder, association can be observed on other parts of the body in 17%–50% of cases LP.[7] Graham Little syndrome is a controversial disorder presents with lesions of classic LPP on the scalp, non-CA of axillary and pubic hair, and keratosis pilarison on the trunk and extremities.[1]

FFA has been originally reported by Kossard et al. in 1997 and refers to a well clinically characterized disorder presenting an inflammatory and lichenoid pattern on histology. The clinical picture presents as symmetric recession of the frontal and temporal hairlines. It is much debated in literature whether FFA represents a variant of LPP or if it is a unique disorder.[8,9]

Although both FFA and the LPP have histological evidence demonstrating that they are the same disease, distinct clinical findings and some arguments of immunological findings from histology leave doubts as to distinguish these entities.[8,10] Comparative studies[12] of scarring alopecia with Langerhans cells and T-lymphocytes argue that each type of scarring alopecia should be carefully evaluated to elucidate cellular components and its effects on stem cells of the bulge region.

In this study, the authors compared the main demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of ten patients with LPP and ten with FFA. Compared to previous studies, our population comprised solely menopausal women in both groups, although there are reports of the disease affecting both men and women in the reproductive phase in 5% of cases, with no consistent association grounded in hormonal changes to date.[12]

The main clinical signs observed in our patients with FFA were similar to those commonly described in literature,[10] including symmetrical and progressive frontotemporal recession, also known as a “band-like” distribution, follicular keratosis and erythema, atrophic and pale skin devoid of hair follicles, thinning or total loss of eyebrows, and absence of vellus hair in the hairline. This clinical pattern of involvement occurred in 100% of cases clinically classified with FFA. The patients with LPP presented had multifocal pattern alopecia, localizated, mainly in the parietal region and vertex, and most often diffuse plaques that progressively coalesced producing large areas of alopecia.[8]

The patients with FFA presented pruritis on the scalp (60% of cases) and the patients with LPP presented burning (30%) and pruritis (30%) as the symptoms. Perifollicular scaling stands out in 80% of LPP cases and 50% of FFA cases.[9] The involvement of other areas by LPP was not reported in any FFA case, unusual association in other reports in literature.[8] In our series, two patients with LPP presented manifestations of oral LPP, less than the literature in which it varies from 28% to 50% in LPP cases with other sites in the body manifestations of lichen planus (LP).[12,13] Partial or complete loss of eyebrows could be seen in most patients with FFA, but the loss of hair in other parts of the body occurred in only two patients with FFA, one with loss of axillary and vulvar hair and another one with loss of additional hair on the upper limbs, compared to the frequency in the literature that presents a range of 0%–37%.[8] Hypothyroidism was present in 20% of cases studied, suggesting an autoimmune mechanism in the pathogenesis of these diseases.[8] Other authors show a variation of 16.5%–30%.[12]

Histopathology findings evidenced reduced number of hair follicles and perifollicular fibrosis in both disorders. Immunofluorescence findings resulted positive in 50% of FFA cases, showing predominantly cytoid bodies in the papillary dermis of IgM and in 40% showing presence of moderate, granulous, and continuous IgM immunofluorescence in the epidermal and follicular basement membrane zone. In 30% of LPP cases, there was moderate, granulous, and continuous IgM immunofluorescence in the epidermal and follicular basement membrane zone and 40% had cytoid bodies in the papillary dermis of IgG, IgA, and IgM [Table 1]. Vañó-Galván et al. in a multicenter review hypothesized that FFA, although presenting identical histopathology, is not a simple variant of LPP but a distinct entity within several differences.[12] According to Poblet et al., in general, FFA tends to show much more apoptosis and less inflammatory infiltrate than LPP.[10] For them, it is questionable whether FFA can be a considerade variant of LPP just because they share a common inflammatory reaction pattern. Although there are controversial findings in literature regarding inflammatory infiltrate density and apoptosis, our evaluation did not show statistical significance in the comparative analysis of the intensity of infiltration.[10] The DIF findings are nonspecific showing IgM deposit and less frequently IgA, IgG, and C3 representing the cytoid bodies around the follicle.[11] In our study, 40% of LPP cases and 50% of FFA cases showed a positive ID to some immunoglobulin and/or complement. Further studies will be needed to draw definite conclusions.

The Langerhans cells are responsible for antigen presentation for reaction mediated by T-lymphocytes.[14] Some studies demonstrate the presence of Langerhans cells (positive CD1a) in normal follicle predominantly in the infundibulum region.[14] An increase in these inflammatory cells in the infundibulum and in the bulge in LPP has been demonstrated,[4] the area where the follicular stem cells are located which may explain atrophy and the scar as a result from the damage to these cells. The various classes of alopecia have similar mechanisms of inflammation but diverge at some point in its pathogenesis.[15,16]

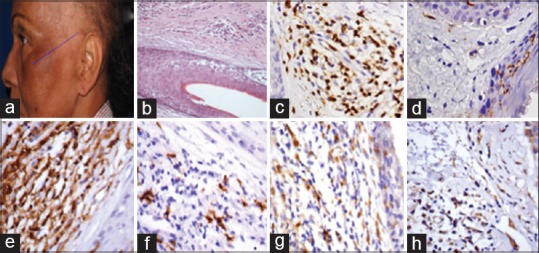

Concerning the expression of CD1a, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD68, and IDO, no significant differences could be elicited in immunohistochemical studies [Table 2 and Figures 1, 2].[6]

Figure 1.

Patient with lichen planopilaris (a); transversal section from a lichen planopilaris case (H and E, ×60) (b); expression of CD1a (c), CD3 (d), CD4 (e), CD8 (f), CD68 (g), 2,3-dioxygenase indoleamine (h) tested by immunohistochemistry

Figure 2.

Patient with frontal fibrosing alopecia (a); transversal section from a frontal fibrosing alopecia case (H and E, ×60) (b); expression of CD1a (c), CD3 (d), CD4 (e), CD8 (f), CD68 (g), 2,3-dioxygenase indoleamine (h) tested by immunohistochemistry

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Otberg N, Wu WY, McElwee KJ, Shapiro J. Diagnosis and management of primary cicatricial alopecia: Part I. Skinmed. 2008;7:19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2007.07163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moure ER, Romiti R, Machado MC, Valente NY. Primary cicatricial alopecias: A review of histopathologic findings in 38 patients from a clinical university hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63:747–52. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000600007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElwee KJ. Etiology of cicatricial alopecias: A basic science point of view. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:212–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harries MJ, Meyer K, Chaudhry I, E Kloepper J, Poblet E, Griffiths CE, et al. Lichen planopilaris is characterized by immune privilege collapse of the hair follicle's epithelial stem cell niche. J Pathol. 2013;231:236–47. doi: 10.1002/path.4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiang C, Sah D, Cho BK, Ochoa BE, Price VH. Hydroxychloroquine and lichen planopilaris: Efficacy and introduction of Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index scoring system. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:387–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dawber R, Van Neste D, editors. Hair and Scalp Disorders. Boca Raton, USA: Taylor and Francis; 2004. Cicatricial alopecia; pp. 140–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assouly P, Reygagne P. Lichen planopilaris: Update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2009;28:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: A frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehregan DA, Van Hale HM, Muller SA. Lichen planopilaris: Clinical and pathologic study of forty-five patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27(6 Pt 1):935–42. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70290-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poblet E, Jiménez F, Pascual A, Piqué E. Frontal fibrosing alopecia versus lichen planopilaris: A clinicopathological study. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:375–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF. Histopathologic evaluation of alopecias. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:236–59. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200606000-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vañó-Galván S, Molina-Ruiz AM, Serrano-Falcón C, Arias-Santiago S, Rodrigues-Barata AR, Garnacho-Saucedo G, et al. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A multicenter review of 355 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:670–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: A review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:955–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moresi JM, Horn TD. Distribution of Langerhans cells in human hair follicle. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:636–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1997.tb01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mobini N, Tam S, Kamino H. Possible role of the bulge region in the pathogenesis of inflammatory scarring alopecia: Lichen planopilaris as the prototype. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:675–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutchens KA, Balfour EM, Smoller BR. Comparison between Langerhans cell concentration in lichen planopilaris and traction alopecia with possible immunologic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;33:277–80. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181f7d397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]