Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the level of awareness of outpatients, and their preferences regarding the appropriate time for discussions regarding do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in Saudi Arabia.

Methods:

This cross-sectional, self-administered survey was conducted at King Fahd Medical City, a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between December 2012 and January 2013. Demographic parameters of the participants were analyzed by frequency distribution, and the data on their responses by percentage analysis.

Results:

The survey participants constituted 307 randomly selected outpatients/caregivers presenting for outpatient care at primary and tertiary care centers, 70% were female. Three-fourths of the participants had heard of DNR order, of which 50% defined it accurately. Ninety percent preferred a discussion while ill, and 10% while healthy. More than 70% expressed willingness to share the decision with their spouses/family members. Almost one-third believed DNR orders were consistent with Islamic beliefs, almost as many believed they were inconsistent, and almost a third did not take either position. Almost all the participants showed a willingness to learn more about the order.

Conclusion:

A divided opinion exists regarding religious and ethical aspects of the issue among the participants. However, almost all the participants showed a willingness to learn more about the DNR order.

The do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order is a decision by the patient or an individual regarding his/her end of life medical care to opt out of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in the event of cardiac, or pulmonary arrest, or both. The treatise Fundamentals of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation, declared in 1965 that, “the physician should concentrate on resuscitating patients who are in good health preceding arrest, and who are likely to resume a normal existence”.1 This implies by default, in the absence of a DNR order agreement, that the physician proceeds with CPR with hospitalized patients in the case of cardiopulmonary arrest. However, it has been observed that many patients with a terminal illness would opt for a DNR order if an informal discussion takes place at the right time between the patient and the physician. A patient may prefer chemotherapy, surgery, or other kinds of treatments, and still also wish to sign a DNR order agreement. The patients’ preferences before a cardiac arrest may not reflect his standpoint on a DNR order. Such discussions are often delayed in the hospital setting, which compromises patient autonomy.2

Most patients are never asked by a physician about their wishes regarding CPR. According to the SUPPORT (Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment),3 only 25% of the seriously ill elderly patients ever discussed CPR with their physician. During most of the cases, a decision on the DNR order is made by family members, and not by the patients.3 However, numerous large-scale studies on outpatients have suggested that patients wish to directly discuss CPR with their physicians while they are still healthy.4 This tendency further increases in patients when the patient realizes his health condition is deteriorating. The desire of the patients to participate in clinical decision-making, especially when life-sustaining treatments are involved, is widespread and the DNR order is the only framework that provides such an opportunity under legal means.4 In the absence of an informed discussion between a patient and physician, the patient, and his family are left with little knowledge on the possibilities of entering into a DNR order agreement.2 This is clearly reflected in the fact that television is the major source of information on CPR for the public.5 Communication between physicians, patients, and families is crucial to establish clarity on the nature of the patient’s illness and its prognosis, which would help them to make a decision about a DNR order. This is an issue that requires further attention and faces many challenges in implementation.4,6

Religious declarations or fatwas are accepted as a source for laws in Saudi Arabia in many ethical, including end-of-life, issues. In 1988, a fatwa was issued by the General Presidency of Scholarly Research and Ifta in Riyadh (Fatwa 12086).7 This has been considered as the basis for the DNR order policy in this country since then. The policy stipulates that judging resuscitative efforts to be of no avail and issuing a DNR order is carried out by 3 “specialized and trustworthy” physicians. The patient’s family or legal guardian needs not be consulted while issuing the order. The same fatwa indicates 6 situations for issuing a DNR order: if the patient arrives dead at the hospital, if the panel of physicians certifies that the illness is untreatable and death is imminent, if the patient is medically unfit for resuscitation, if the patient is suffering from advanced heart or lung disease or repeated cardiac arrest, if the patient is in a vegetative state, and if resuscitation is considered pointless.8 The local guidelines regarding issuing a DNR order entitle a DNR patient to all treatments except for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. All interventions that ensure patient’s comfort and dignity will be offered.8 In practice, all hospitals in Saudi Arabia abide by the core of this policy, namely, 3 consultants signing a DNR order. However, case study data on DNR orders revealed a considerable extent of heterogeneity in implementing the law, particularly on patient autonomy, the involvement of the patient and his family in the decision-making, and the characteristics of the patient that may influence the physician’s decision in signing a DNR order.8,9

Earlier studies from Saudi Arabia have evaluated the perspectives and practices of interns and residents toward DNR policies.4,8,10 However, the level of awareness of Saudi outpatients regarding DNR remains to be understood. Hence, this study was planned to determine the level of awareness of outpatients, their preferences regarding the appropriate time for discussions regarding DNR order, and to explore their ethical standpoints.

Methods

This study was conducted at King Fahd Medical City, Riyadh, a major tertiary care hospital in Saudi Arabia with the permission of the Institutional Review Board (IRB; numberH-01-R-012) between December 2012 and January 2013. Across-sectional survey was conducted with a self-administered questionnaire. Three hundred and seven visitors from the outpatient unit of the hospital were randomly enrolled. Inclusion criteria were outpatients (medical, surgical, cardiovascular and oncology patients) and caregivers (sons and daughters of the patients) attending the outpatient unit and willing to participate. Individuals below 15 years and above 70 years were excluded. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Nine questions including open ones demanding specific answers were structured to collect data on demographics; the definition of a DNR order if they had ever heard of it; whether they would prefer to inform their parents regarding the DNR order decision; when, and with whom they would prefer DNR order discussions to take place; whether they perceived DNR order decisions to be anti-religious; and whether they would like to learn more about DNR orders. A response was considered as complete if all the questions were answered. Demographic parameters of the participants were analyzed by frequency distribution, and the data on their responses by percentage analysis.

Descriptive statistical analysis in the form of frequency distribution analysis was used and data were summarized to describe the data characteristics. Categorical data were expressed as frequency (percentage). The Statistical Package for Social Science v.19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

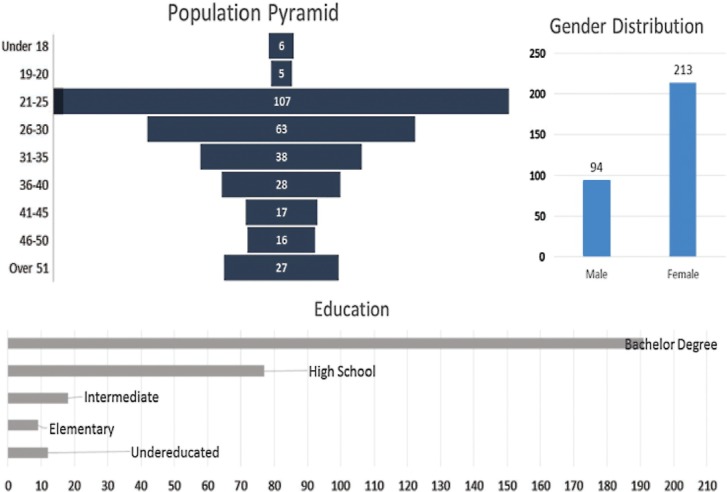

All the 307 participants completed the survey (100% response rate). Seventy percent of the participants were females. One third of the subjects were young adults aged 21-25 years, whereas 62% were bachelors (Figure 1). Most respondents (75%) had heard the term do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order, of which only 50% were able to provide a correct definition of the term. Almost half (51.7%) felt that they would not mind informing their parents regarding the DNR order decision. Regarding the best time to have a discussion about a decision on DNR order, almost 90% thought of it as when a person is diagnosed with any illness. Only 10% felt that the discussion should be carried out when the patient is healthy. Most participants (42.6%) were willing to share their knowledge regarding CPR with their spouse, followed by other family members (30%). Among others, elder sons were the preferred members to share the decision. Participants expressed divided opinion regarding the association of religion (namely, Islam) with the DNR order, 34.4% endorsing its agreement with Islamic regulations, 34.3% pointing to disagreement, and 31.3% expressing neutrality on the issue.

Figure 1.

Demographic structure of the participants completing a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order questionnaire.

Discussion

The introduction of the DNR order is a paradigm shift in medical practice worldwide that creates opportunities for better care for terminally ill patients and more judicious use of overstretched resources.11 However, practical implementation of this crucial process often gets hampered, or deviated due to reasons including, but not limited to lack of awareness and clarity of its execution among the stakeholders.12,13 Therefore, there is a need for assessing and enhancing public awareness of this issue.

This study reveals that most of the participants had heard of the terms DNR order (74.9%), and approximately half of them (50.4%) were knowledgeable of the correct definition. Similar trends of awareness and knowledge on the issues of DNR order and CPR have been reported by earlier studies from different parts of the world.14-22 These results highlight the level of awareness among the patient population regarding DNR order and its implications. However, a huge gap exists between awareness and execution of the process.5

In our study, most respondents preferred to discuss the DNR order after developing an illness (90%). This disagrees with the findings from numerous previous studies where patients preferred to discuss the DNR order while they are healthy.10 A possible reason for this may be lack of awareness of the importance of DNR among the public. Hence, increasing public awareness of DNR may motivate people into making a decision on a DNR order even when they are healthy. Most patients preferred discussing DNR orders with either their spouse or the eldest son. A similar preference of family members for any discussion on DNR order was also noted in prior studies.14 Most of the respondents (93%) expressed their desire to receive further information regarding DNR orders, and this could be related to their divided opinions from the religious and ethical points of view.

Study limitations

The major limitations of the current study include small sample size from a single-center with a bias toward a younger age group.

The current study has elucidated the state of awareness regarding DNR order among the general public in Riyadh. Half of the respondents could define the order, but most felt they required more in-depth knowledge. The opinion of the participants regarding compatibility of DNR order in terms of religion and ethics was divided. More education about DNR orders may be needed, including about ethical, religious, and medical aspects.

Further studies should be multi-centered with a larger diverse population. Statistical analysis of correlations between gender, education, ethnicity, and age with DNR order will help in the development of strategies for more effective DNR order implementation.

Footnotes

Ethical Consent.

All manuscripts reporting the results of experimental investigations involving human subjects should include a statement confirming that informed consent was obtained from each subject or subject’s guardian, after receiving approval of the experimental protocol by a local human ethics committee, or institutional review board. When reporting experiments on animals, authors should indicate whether the institutional and national guide for the care and use of laboratory animals was followed.

References

- 1.Jude J, Elam J. Fundamentals of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Philadelphia (PA): F. A. Davis; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead GE, Turnbull CJ. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the elderly: patients’ and relatives’ views. J Med Ethics. 1995;21:39–44. doi: 10.1136/jme.21.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherniack EP. Increasing use of DNR orders in the elderly worldwide: whose choice is it? J Med Ethics. 2002;28:303–307. doi: 10.1136/jme.28.5.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loertscher L, Reed DA, Bannon MP, Mueller PS. Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders: A Guide for Clinicians. Am J Med. 2010;123:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller DL, Jahnigen DW, Gorbien MJ, Simbartl L. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: how useful? Attitudes and knowledge of an elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 1992;152:578–582. doi: 10.1001/archinte.152.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasule OHK. Outstanding ethico-legal-fiqhi issues. Journal of Taibah University Medical Sciences. 2012;6:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alifta.net [webpage on the Internet] Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: The General Presidency of Scholarly Research and Ifta. Fatwas on Medical Issues and the Sick [Fatwa no. 12086] [[Accessed 2016 September 16]]. pp. 322–324. Available from: http://www.alifta.net/Fatawa/FatawaChapters.aspx?languagename=en&View=Page&PageID=299&PageNo=1&BookID=17 .

- 8.Amoudi AS, Albar MH, Bokhari AM, Yahya SH, Merdad AA. Perspectives of interns and residents toward do-not-resuscitate policies in Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2016;7:165–170. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S99441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takrouri MSM, Halwani TM. An Islamic medical and legal prospective of do not resuscitate order in critical care medicine. Internet J Health. 2008;7:1. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aljohaney A, Bawazir Y. Internal medicine residents’ perspectives and practice about do not resuscitate orders: survey analysis in the western region of Saudi Arabia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:393–397. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S82948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwartz SJ, Sieber F. Manual of Geriatric Anaesthesia. Ch. 12. New York (NY): Springer; 2013. The Elderly Patient and the Intensive Care Unit; pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolasora N, Pannala R, Mountantonakis S, Shanmugam B, DeGirolamo A, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, et al. If asked, hospitalized patients will choose whether to receive life-sustaining therapies. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:161–167. doi: 10.1002/jhm.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sivakumar R, Raha R, Funaki A, Ghosh P, Khan SA. Communicating information on cardiopulmonary resuscitation to hospitalised patients. Clin Med (Lond) 2006;6:627–628. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.6-6-627a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shmerling RH, Bedell SE, Lilienfeld A, Delbanco TL. Discussing cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a study of elderly outpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:317–321. doi: 10.1007/BF02595786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gouda A, Al-Jabbary A, Fong L. Compliance with DNR policy in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:2149–2153. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1985-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Mobeireek AF. Physicians’ attitudes towards ‘do-not-resuscitate’ orders for the elderly: a survey in Saudi Arabia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2000;30:151–160. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4943(00)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo B, McLeod GA, Saika G. Patient attitudes to discussing life-sustaining treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1613–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly BM, Magnussen CR, Ross J, Ash J, Papa L, Wagner M. Can we talk? Inpatient discussions about advance directives in a community hospital. Attending physicians’ attitudes, their inpatients’ wishes, and reported experience. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2299–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamel MB, Lynn J, Teno JM, Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Galanos A, et al. Age-related differences in care preferences, treatment decisions, and clinical outcomes of seriously ill hospitalized adults: lessons from SUPPORT. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 Suppl):S176–S182. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siegler EL, Levin BW. Physician-older patient communication at the end of life. Clin Geriatr Med. 2000;16:175–204. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(05)70016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godkin MD, Toth EL. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and older adults’ expectations. Gerontologist. 1994;34:797–802. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.6.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebell MH, Doukas DJ, Smith MA. The do-not-resuscitate order: a comparison of physician and patient preferences and decision-making. Am J Med. 1991;91:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90124-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]