Abstract

Objectives:

To identify and describe the hospital disaster preparedness (HDP) in major private hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Methods:

This is an observational cross-sectional survey study performed in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia between December 2015 and April 2016. Thirteen major private hospitals in Riyadh with more than 100 beds capacity were included in this investigation.

Results:

The 13 hospitals had HDP plan and reported to have an HDP committee. In 12 (92.3%) hospitals, the HDP covered both internal and external disasters and HDP was available in every department of the hospital. There were agreements with other hospitals to accept patients during disasters in 9 facilities (69.2%) while 4 (30.8%) did not have such agreement. None of the hospitals conducted any unannounced exercises in previous year.

Conclusion:

Most of the weaknesses were apparent particularly in the education, training and monitoring of the hospital staff to the preparedness for disaster emergency occasion. Few hospitals had conducted an exercise with casualties, few had drilled evacuation of staff and patients in the last 12 months, and none had any unannounced exercise in the last year.

A mass casualty incident (MCI) is any incident in which emergency medical services resources, such as personnel and equipment, are overwhelmed by the number and severity of casualties.1 During recent decades, major emergencies, crises, terrorist attacks, and disasters are becoming a possibility in any community including Saudi community. These emergency incidents are affecting many people and causing MCIs. This can disrupt the health sector programs and essential services in the community.2 Many lives could be saved if the affected communities were better prepared, with an organized scalable response system and emergency plans. Riyadh is not an exception and might be vulnerable to different types of MCIs. Riyadh is the capital of Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and also its largest city with over 7 million populations that accounts for more than 22% of the population of the whole country. There are 11 governmental hospitals with more than 100 beds capacity in Riyadh. It is considered a strategic and economic requirement to make our hospitals and health facilities, including the private sector, prepared to emergency situations.3

In Saudi Arabia most hospitals in Jeddah faced a critical situation in 2009 due to floods. This raised many questions in the Ministry of Health (MOH) and higher authorities about the preparedness of hospitals not in Jeddah area only, but also in the entire Kingdom. The role and importance of hospitals during disasters is essential to save as many lives as possible.4 Emergency preparedness in the hospitals is a key success factor for any effective emergency and MCI management practices. In fact, hospitals play a significant role in health care infrastructure in a community.5

Recently, Saudi Arabia has become a typical region for natural hazards (floods, storms, earthquake, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), landslides, and so forth) and/or human-made hazards (fires, explosives, structural collapse, transportation event, and so forth) that markedly could affect a large number of people. The MOH realized that making hospitals and health facilities safe from disasters is an essential strategic and economic requirement. The failure of hospitals to face disasters and MCIs and save lives cost KSA too high as compared to the cost of making hospitals safe and well prepared to face MCI.6

The aim of this work was to investigate the hospital disaster preparedness (HDP) in 13 major Riyadh private hospitals in case of MCIs. Although there are controversies on the difference between disasters and MCI, the present study focused on having many casualties as sudden casualties of trauma only in urban healthcare system. Since there are no Saudi national standards for disaster management, this study was carried out as a part of MOH supervising the private hospitals to assess the current situation. This research was carried out as part of Master of Public Health (MPH) requirements and sponsored by the MOH. This study endeavored to establish a better knowledge about the capabilities of private hospitals in Riyadh to respond to MCIs that might occur.

Methods

The present research was an observational cross sectional study involving major private hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. This study was conducted in Riyadh from December 2015 to April 2016. Thirteen private hospitals in Riyadh were included in this investigation. According to information from MOH, there were 15 major large private hospitals (more than 100 beds) in Riyadh. All of them were included, but 2 of them were excluded as it was new and not all specialties and operations were established yet, and there was a fire accident near the place at the time of data collection. The study was limited to hospitals with a capacity of 100 or more beds as such organizations were assumed to be more inclusive in their technical, administrative, and institutional structures and could have a role during disaster of MCIs.

The inclusion criteria were: Riyadh Private Hospitals more than 100 beds capacity, all the specialties Hospitals (covering all medical and surgical services), full operation, had emergency department and intensive care unit (ICU), and with in-patient pharmacy. The exclusion criteria were: hospitals less than 100 beds, and restricted specialty hospitals.

Data was collected through a questionnaire with both open ended and closed questions through an interview with key informants in the hospital such as the hospital administrators, emergency managers and/or a member of the hospital emergency preparedness and response committee. Data were recorded via taking notes during interviews and collected through semi-structured interviews. Personal site visits and contact with subjects were used to approach the participants. All of the subjects who were approached agreed to participate in the study. The main researcher himself conducted the interviews and he was not a worker at any of the hospitals, and relationships between him and participants were not established before the interviews. All interviews were conducted in the offices of the participants while ensuring a private and secure environment. Interviews lasted for a minimum of 30 minutes and maximum for an hour. Data collection was ended after interviewing the hospital key informants.

Interview questions were adopted from WHO toolkit for assessing health-system capacity for crisis management and hospital emergency response checklist.7,8 Questions were mainly related to preparedness of the hospital to MCI and the capacity of the hospital for surge in emergency events. The tool was modified for use reviewed by experts in the field, and a pilot study was conducted at King Saud University Medical City Emergency and Disaster Preparedness Committee, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the College of Medicine, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia (Ref. No. 16/0526/IRB on 25.01.2016). The participants were assured that the name of the hospital, or the participants will not be declared and cannot be traced by any mean. They were reminded that there are no standards for disaster management were issued by the MOH, and appreciated that all activities in this regards are carried out by the hospital eager to improve and secure their operations and meet any international quality accreditation they chose. No negative implications of any mean were intended to the participating hospitals.

The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Science Software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The findings of the present research were based on the information obtained during interviews with the hospitals key informant that answered the open-ended and closed questions in the questionnaire and the disaster plan checklist prepared by the researcher.

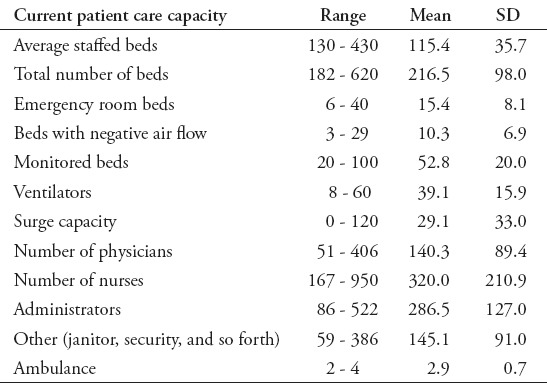

Regarding the staff workers power, the total hospital physician ranged from 51 to 406 (140.6 ± 89.4), while the total number of nurses ranged from 167 to 950 (320 ± 210.9). The number of ambulances owned by the 13 hospitals ranged from 2 to 4 (2.9 ± 0.7). There was only one hospital of the thirteen had an on-site helipad. Two hospitals of the 13 have no blood bank and if they needed blood they had an agreement with another hospital to supply them; however, they did not know how long it will take to receive the blood from them. All of the 13 hospitals had fatalities management. All the hospitals have internal pharmacy. Eight (61.5%) have a stockpile of antidotes (for organophosphate and cyanide) maintained by the pharmacy. Most of the pharmacies (92.3%) monitored daily medication usage on a changing baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Current patient care capacity and total hospital staff in the studied hospitals.

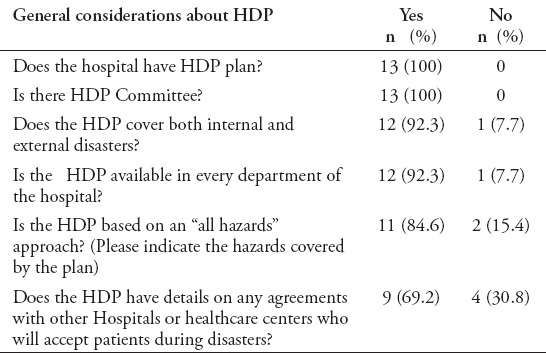

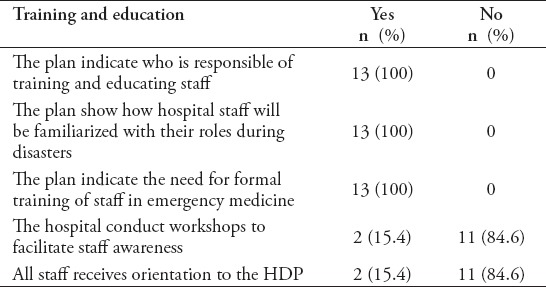

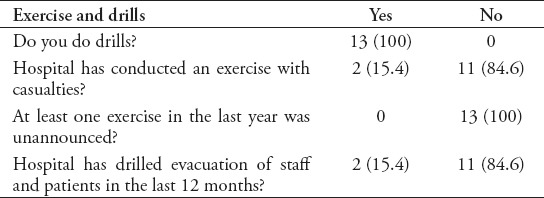

Table 2 demonstrated that all the 13 hospitals had HDP plan and reported to have HDP committee. In 12 (92.3%) hospitals the HDP covered both internal and external disasters and HDP was available in every department of the hospital. The HDP in 11 hospitals (84.6%) was based on an “all hazards” approach. There were an agreements with other hospitals to accept patients during disasters in 9 facilities (69.2 %) while 4 (30.8%) did not have such agreement. All hospitals reported who was responsible of training and educating of the staff about the HDP to make the hospital staff familiarized with their roles during disasters. All hospitals had plan indicate the need for formal training of staff in emergency medicine. In only 2 (15.4%) hospitals the key informants said that it had conducted workshops to facilitate staff awareness and to make their staff receive orientation to HDP (Table 3). All hospitals reported to do drills for the HDP, but when asked about their reference only 2 hospitals showed it. Moreover, none of the hospitals conducted any unannounced exercises in the last year. Moreover, only 2 (15.4%) of the studied hospitals had conducted exercise with casualties, and had drilled evacuation of staff and patients in the last 12 months (Table 4).

Table 2.

Hospital disaster plan (HDP) in the studied hospitals.

Table 3.

Training and education about HDP in the studied hospitals.

Table 4.

Exercise and drills about HDP in the studied hospitals.

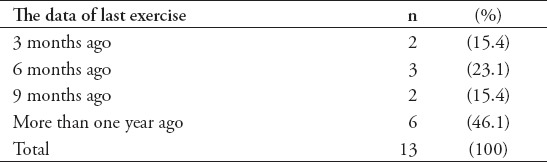

Two (15.4%) hospitals did exercise for the HDP in the last 3 months, 3 (23.1%) did it in the last 6 months, 2 hospitals (15.4%) did it in the last 9 months, and 6 (46.1%) did not perform any exercise to the HDP during the last 12 months (Table 5).

Table 5.

The date of last exercise for HDP in the studied hospitals.

Discussion

Despite that MCIs were rare in the last decades in Riyadh, it is essential that hospitals are prepared to disasters due to the possibility of an emergency event causing increase in MCI. The number of private hospitals is increasing in Riyadh and this prompted the researcher to study disaster preparedness at its large private hospitals. The present study used a HDP assessment toolkit to determine the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the hospital managers at 13 major private hospitals in Riyadh regarding disaster and emergency preparedness in case of MCI.

The present work showed that there was no single hospital of the studied ones faced an actual disaster, or MCIs since it were established, and so the emergency disaster plan (EDP) was not experienced until now. This study found that there was a plan for HDP in each of the 13 hospitals included in the study; however, certain components of the plan were deficient or missing in some hospitals. During the interview, it was noticed that many of the respondents did not believe that MCI’s is expected in Riyadh and they only prepared the plan and make sure that it would be implemented. This was confirmed when it was noticed that exercises and drills for the HDP were not performed in most hospitals in the last year and may be ever. Hospitals need a well-documented and tested plan in order to respond effectively and efficiently to disasters. A disaster plan is not an aim by itself and having one does not mean that the hospital is prepared when MCI occurs.9,10

The results of the present work showed that most of the plans in the studied hospitals were set its disaster risk profile of the hospital and objective in relation to motor vehicle accidents and floods and is not adequately cover the “all hazards” process and “whole health” approach as recommended by the WHO.11 The HDP might need to be reconstructed and reviewed in order to include response to internal disasters such as fire, collapse of hospital, flooding and external disasters such as terrorist attack, storms, earthquake, landslides, explosives, structural collapse, transportation event and so forth).12 According to Adini et al13 the national healthcare systems in a country were required to prepare an effective response model to manage emergencies due to MCIs. Planning for disaster preparedness should be envisioned as a process rather than a production of a solid plan. To guarantee proper emergency preparedness necessitates a structured methodology to put EDP. This plan will enable an objective assessment of the level of readiness to respond during MCIs.

Most of the studied hospitals were found to have weaknesses in terms of training and education, and monitoring and evaluation of EDP. There was weakness in the disaster preparedness in conducting no workshops and training to assist staff awareness and to make them receive orientation to the hospital EDP. The present results were in agreement with the study of Bajow and Alkhalil14 that investigated the HDP in Jeddah area. They reported that hospitals in Jeddah area had tools and indicators in hospital preparedness, but with lack of training and management during disaster.

Most of the key informants that have been interviewed from the private hospitals in Riyadh believed that Riyadh was less subjected to natural disasters as it had no history of natural disasters. However, they admitted of the possibility of man-made catastrophe, or terrorism attack as a cause of MCIs. One of the raised worry of the private hospitals’ administrations was the cost and bills for management of victims from MCIs. They proposed that there should be a clear written agreement, or memorandum between MOH and private hospitals on the hospital bills for patients received during MCIs. Such agreement will protect the patients send to private hospitals during disasters from facing huge hospital bills and high fees in the private sector and will also keep the rights of the private hospitals to receive back what it spent to treat patients from MCIs.6

Abosuliman et al15 reported that the disaster preparedness in Saudi Arabia is a key success factor for any effective disaster management practices. The authors stressed on the top 5 areas for future attention: training of response teams, identification and coordination of the organizational responsibilities, community awareness, and preparedness. Their results showed that the disaster mitigation was found to be very important for the representatives of public authorities. They found that the population acknowledged the risk of natural and human-initiated disasters, and were generally responsive to disaster threats, but lacked community-based organization. They concluded that continually training disaster responders with best practices and preparedness is paramount to successful disaster crisis prevention and management.

The Saudi government represented in the MOH is the decisive ultimate authority in the management of health effects from emergency events such as MCIs as part of its overall responsibilities for the safety and security of the country. There is a need for financial framework for funding private hospital preparedness and mass casualty costs. In the present financial situation, the pay is directed only for the immediate costs of patients; however, there is a need for a means to pay also for the planning, education, standby supply, and training costs of preparedness.16

The study was limited by the inadequate local literature. Few researches in KSA have been performed on the preparedness of the Governmental hospital and none were found about private hospitals up to the date of performing the study. Moreover, not all private hospitals in Riyadh were included in the study and no comparison with performed Governmental hospitals.

In conclusion, all of the hospitals had well prepared documents to prove that it was prepared to face the emergency event of MCIs. However, most of the weaknesses were apparent particularly in the education, training, and monitoring of the hospital staff to the preparedness for disaster emergency occasion. Most of the hospitals did not conduct workshops to facilitate staff awareness on the EDP. Few hospitals included disaster drills in their EDP or drills involving communication and coordination with other organizations in the region dealing with disasters. Further research is recommended to be carried out in order to investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of the healthcare workers at these private hospitals regarding EDP and the hospital disaster preparedness.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Mistovich JJ, Karren KJ, Hafen B, editors. Prehospital Emergency Care. 10th ed. New Jersey (NJ): Prentice Hall; 2013. p. 866. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zane RD, Prestipino AL. Implementing the hospital emergency incident command system: An integrated delivery system’s experience. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19:311–317. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Born CT, Briggs SM, David L, Ciraulo DL, Frykberg ER, Hammond JS, Hirshberg A, et al. Disasters and mass casualties: i. general principles of response and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:388–396. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welzel TB, Koenig K L, Bey T, Visser E. Effect of staff surge capacity on preparedness for a conventional mass casualty event. West J Emerg Med. 2010;11:189–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adini B, Goldberg A, Laor D, Cohen R, Zadok R, Bar-Dayan Y. Assessing levels of hospital emergency preparedness. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2006;21:451–457. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00004192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. International Strategy for Disaster Reduction and World Health Organization (WHO) 2008-2009 World Disaster Reduction Campaign. Hospitals safe from disasters, reduce risk, protect health facilities, save lives. [[cited 2009]]. Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/2009/campaign/pdf/wdrc-2008-2009-information-kit.pdf .

- 7.World Health Organization. Hospital emergency response checklist. An all-hazards tool for hospital administrators and emergency managers. [[cited 2011]]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/148214/e95978.pdf?ua=1 .

- 8.World Health Organization. Strengthening health-system emergency preparedness. Toolkit for assessing health-system capacity for crisis management. [[cited 2012]]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/chafea/documents/health/leaflet/who-toolkit.pdf .

- 9.Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, DeAtley C, Barbisch D, Bogdan GM, et al. Health care facility and community strategies for patient care surge capacity. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bagaria J, Heggie C, Abrahams J, Murray V. Evacuation and sheltering of hospitals in emergencies: a review of international experience. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2009;24:461–467. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00007329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaji AH, Lewis RJ. Hospital disaster preparedness in Los Angeles county. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:1198–1203. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neill PA. The ABC’s of disaster response. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:259–266. doi: 10.1177/145749690509400403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adini B, Goldberg A, Laor D, Cohen R, Bar-Dayan Y. Factors that may influence the preparation of standards of procedures for dealing with mass-casualty incidents. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2007;22:175–180. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00004611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajow NA, Alkhalil SM. Evaluation and analysis of hospital disaster preparedness in Jeddah. Health. 2014;6:2668–2687. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abosuliman SS, Kumar A, Alam F. Disaster preparedness and management in Saudi Arabia: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic and Management Engineering. 2013;7:1979–1983. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta S. Disaster and Mass casualty management in a Hospital: How well are we prepared. J Postgrad Med. 2006;52:89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]