Abstract

Objectives

A number of observational studies have reported that, in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), β blockers (BBs) decrease risk of mortality and COPD exacerbations. To address important methodological concerns of these studies, we compared the effectiveness and safety of cardioselective BBs versus non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (non-DHP CCBs) in patients with COPD and acute coronary syndromes (ACS) using a propensity score (PS)-matched, active comparator, new user design. We also assessed for potential unmeasured confounding by examining a short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome.

Setting and participants

We identified 22 985 patients with COPD and ACS starting cardioselective BBs or non-DHP CCBs across 5 claims databases from the USA, Italy and Taiwan.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Stratified Cox regression models were used to estimate HRs for mortality, cardiovascular (CV) hospitalisations and COPD hospitalisations in each database after variable-ratio PS matching. Results were combined with random-effects meta-analyses.

Results

Cardioselective BBs were not associated with reduced risk of mortality (HR, 0.90; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.02) or CV hospitalisations (HR, 1.06; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.23), although statistical heterogeneity was observed across databases. In contrast, a consistent, inverse association for COPD hospitalisations was identified across databases (HR, 0.54; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.61), which persisted even within the first 30 days of follow-up (HR, 0.55; 95% CI 0.37 to 0.82). Results were similar across a variety of sensitivity analyses, including PS trimming, high dimensional-PS matching and restricting to high-risk patients.

Conclusions

This multinational study found a large inverse association between cardioselective BBs and short-term COPD hospitalisations. The persistence of this bias despite state-of-the-art pharmacoepidemiologic methods calls into question the ability of claims data to address confounding in studies of BBs in patients with COPD.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute coronary syndromes, cardioselective β-blockers, mortality, COPD hospitalizations, unmeasured confounding

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A growing body of observational studies suggests that β blockers (BBs) may decrease risk of mortality and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations in patients with COPD; most studies compared prevalent BB users to non-users.

This study used an active comparator, new user cohort design to examine the association between BBs and clinical outcomes and to assess potential remaining unmeasured confounding using data from five claims databases in the USA, Italy and Taiwan.

The study applied a variety of sensitivity analyses, including propensity score (PS) trimming, an high-dimensional PS matching technique and restricting to high-risk patients, to evaluate the consistency of results.

Although this multinational study was conducted with a common protocol, the inherent variations in healthcare systems and data structures across countries necessitated certain database-specific modifications to the protocol.

Owing to analytic flexibility, we conducted sensitivity analyses in the three US databases only.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has profound health impacts worldwide1 2 and usually coexists with cardiovascular (CV) morbidity.3–6 CV risk reduction is therefore a major focus in COPD management. β blockers (BBs) are a cornerstone treatment for improving survival and reducing CV morbidity in patients with coronary artery disease.7–10 The cardioprotective benefits of BBs are expected to extend to patients with COPD. However, those with COPD have generally been excluded from randomised controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of BBs in patients experiencing myocardial infarction (MI).7 9 In addition, while the targets of BBs in treating CV disease are β-1 receptors predominantly found in cardiac tissues, BBs can also block β-2 receptors in the respiratory system, causing bronchospasm and increasing the risk of COPD exacerbations.11 Therefore, in clinical practice, physicians may be reluctant to prescribe BBs to patients with COPD.6 12 One study found that, among patients hospitalised for acute MI, those with COPD had 56% lower odds of being treated with BBs as compared to those without COPD.12

Despite these safety concerns, a growing body of observational studies suggests that BBs may have cardioprotective effects in COPD patients.13–22 One meta-analysis of observational studies reported a 36% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with BB use in patients with coronary heart disease and COPD.23 However, these studies have important methodological limitations. In particular, most of these studies focused on prevalent users of BBs13–22 and used non-users of BBs as the comparator group.13–21 Patients who remain on BB treatment for a long time may be less susceptible to an outcome of interest as compared to those just starting the drug. The prevalent user design is therefore vulnerable to biases due to depletion of susceptible patients.24 25 Treated patients may also differ from untreated patients in important ways, which can create strong confounding, especially when the indication for treatment is a risk factor for the outcome(s) of interest.24 The non-user comparator approach is also vulnerable to immortal time bias.26 These methodological issues may explain the paradoxical COPD hospitalisation findings reported in these studies and perhaps even the reported survival advantage.

Drug safety and comparative effectiveness studies are increasingly using multiple databases across various countries.27–29 The larger sample size afforded by multidatabases studies facilitates the application of robust study designs and, by using a common protocol, such studies enable investigators to leverage differences in the healthcare systems in the assessment of unmeasured confounding, treatment effect heterogeneity and generalisability across diverse populations, while holding constant the design and analytic approach. In the present study, we used multiple databases from three countries to: (1) address important shortcomings of prior studies by comparing the effectiveness and safety of BBs in patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and COPD using a propensity score (PS)-matched, active comparator, new user cohort design; and (2) assess for potential remaining unmeasured confounding by examining a short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome.

Methods

Data source

We identified eligible cohorts from five databases in the USA, Italy and Taiwan: (1) the Optum Research Database (Optum); (2) pharmacy claims data from the Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly program (PACE) in Pennsylvania linked to Medicare claims data; (3) pharmacy claims data from the Pharmaceutical Assistance for the Aged and Disabled program in New Jersey (PAAD) linked to Medicare claims data; (4) the population-based Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy, database (RER) and (5) the population-based Taiwan National Health Insurance database (NHI). These databases contain demographic and enrolment records, hospital admissions, outpatient visits (except in RER), outpatient pharmacy dispensing claims and death information. These five databases cover the period from 1994 through the end of 2013 and represent diverse source populations across countries with different health insurance programmes (see the online supplementary materials for details).

bmjopen-2016-012997supp.pdf (2.1MB, pdf)

Study population and study drugs

From each database, we identified patients who were hospitalised for ACS, had a COPD diagnosis before the ACS hospitalisation discharge date and initiated a cardioselective BB or non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (non-DHP CCB) within 90 days following hospital discharge (see the online supplementary materials for details). Codes used to identify study drugs are provided in online supplementary table S1. The index date was defined as the date of the first postdischarge prescription of a study drug. To focus on initiators, patients with any use of these drugs before the first postdischarge prescription were excluded. Cardioselective BBs were chosen as the exposure of interest in alignment with prior studies.13–22 Initiators of non-DHP CCBs were selected as the referent group since guidelines recommend non-DHP CCB treatment in patients with ACS who have a contraindication to BBs and have no other contraindications (eg, severe left ventricular dysfunction).30 31

We excluded patients without continuous enrolment for at least 180 days before the ACS hospitalisation admission date (see the online supplementary materials for details), those with age <20 years (Optum, RER, NHI) or 65 years (PACE, PAAD) or more than 120 years, and those who simultaneously initiated study drugs from both exposure groups on the index date.

Outcomes and follow-up

We selected all-cause mortality and CV hospitalisations as outcomes of interest. CV hospitalisations were defined as first hospitalisation for a composite CV event, including acute MI, unstable angina and congestive heart failure (CHF) following the index date. We conducted analyses for the composite CV event and individual components of the outcomes separately. We also examined hospitalisation for COPD as an outcome. CV and COPD hospitalised events were defined using validated claims-based algorithms with positive predictive values of 80% for acute MI,32 88–94% for CHF33 and 86% for COPD34 (see the online supplementary materials for outcome ascertainment; all outcomes were based on primary inpatient diagnoses). While animal models have suggested that chronic BB use may upregulate β-2 adrenoceptors and attenuate pulmonary inflammation,35 36 meta-analyses of randomised trials have found that there is no significant effect of cardioselective BB on pulmonary function in the short term (single dose to 4 months).37 38 We therefore assessed for the presence of bias by using a short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome as a negative control, defined as a COPD hospitalisation within 30 days following the index date. We assumed that, even if BBs improve COPD in the long term, a large apparent protective association in the short term would not be causal and would reflect bias, such as confounding due to unmeasured baseline differences between treatment groups.

In the primary ‘first exposure carried forward’ analysis, we followed patients from the index date to the earliest of outcome occurrence, death, disenrollment from the health insurance programme or the end of study. In the secondary ‘as-treated’ analysis, follow-up ended on the first of treatment discontinuation or change, outcome occurrence, death, disenrollment from the health insurance programme or the end of study. Treatment discontinuation was defined using a grace period of up to 14 days between the end of one prescription and the date of the next prescription, if any. Treatment change was defined as a dispensation of a drug in the other exposure group. Given the absence of information on days supply in the RER database, we assigned a proxy based on the WHO's Defined Daily Dose methodology (online supplementary table S1). This approach has shown good concordance with days supply for chronically used medications.39

Covariates

Information on potential confounders included demographic data, year of index date, enrolment duration, resource utilisation, comorbidities and other medication use. Resource utilisation was evaluated during the 180-day baseline period preceding the index date. CV-related comorbidities and medication use were assessed in two separate periods: a chronic phase before the ACS hospitalisation admission date (data were traced back as far as possible within each database); and an acute phase between the ACS hospitalisation date and the index date. Non-CV comorbidities and medication use were evaluated using all available data prior to the index date. Using all available claims information has been found to better reduce bias under most conditions as compared to a fixed look-back period.40 41 Details on covariate ascertainment are provided in online supplementary tables S2 and S3.

Statistical analysis

Using the predefined covariates described above, we estimated baseline PSs using logistic regression models to predict the probability of receiving cardioselective BBs versus non-DHP CCBs. Non-categorical covariates (eg, age) were included in the PS model as linear terms. Since we had many more cardioselective BB initiators than non-DHP CCB initiators, we conducted variable-ratio matching (up to 10 cardioselective BB users to each non-DHP CCB user) using a nearest-neighbour algorithm with a maximum matching caliper of 0.01 on the PS scale.42

Variable-ratio matching produces covariate balance within matched sets but not marginally in the overall matched population.42 We therefore randomly sampled one cardioselective BB user from each set of patients matched to each non-DHP CCB user and examined whether adequate balance in covariates was achieved between treatment groups using standard differences43 among this sample (1:1 random-sample matched cohort). We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate HRs and 95% CIs. To account for the variable-ratio matching, the Cox model was stratified on PS-matched sets.

We identified study cohorts, extracted information on variables, fit PS models and performed PS matching separately within each database. We computed standardised differences across the databases for each variable using pooled means and SDs. The random-effects meta-analysis was used to generate summary estimates across all databases. Statistical heterogeneity across databases was quantified using the I2 statistic.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

To mitigate potential unmeasured confounding, four sensitivity analyses were performed in the US databases. First, the maximum matching caliper was reduced to 0.005. Second, before PS matching, asymmetric PS trimming44 was applied to exclude those with PS values less than the 2.5th centile or greater than the 97.5th centile of the PS distribution in cardioselective BB users and non-DHP CCB users, respectively. Third, high-dimensional PSs (hd-PSs) were used to identify and include an additional 100 empirically identified variables in the PS model.42 45 Finally, we restricted to high-risk patients, defined as those with COPD hospitalisations and use of bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids in the window between 180 days before the index hospital admission date and the index date. To examine the influence of prescribing patterns and treatment strategies over time, we also conducted subgroup analyses by year of the index date.

Results

Patients

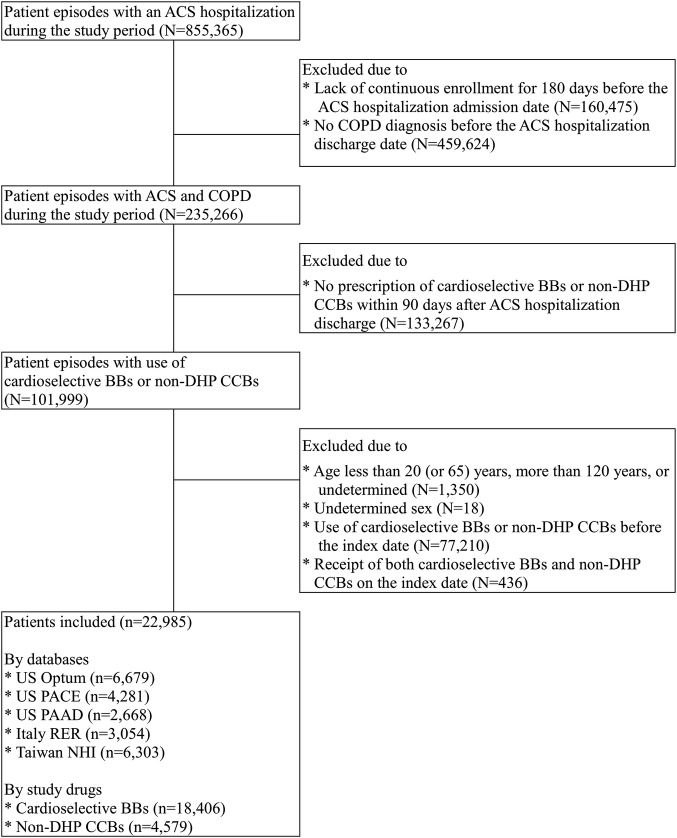

Among 22 985 eligible patients, 18 406 initiated cardioselective BBs (80.1%) and 4579 initiated non-DHP CCBs (18.9%) (figure 1 and see online supplementary table S4). Most patients (>80%) started treatment within 30 days after the ACS hospitalisation discharge. The mean age of the cohort was 71 years and 59% were men. In general, non-DHP CCB initiators were older and had a longer length of stay for the index ACS hospitalisation, a longer history of COPD and higher resource utilisation. Cardioselective BB initiators were more likely to have received coronary revascularisation procedures, have had a diagnosis of MI, peripheral vascular disease and hyperlipidaemia and have used ACE inhibitors, fibrates and statins. Non-DHP CCB initiators were more likely to have had a diagnosis of angina, arrhythmia and CHF and taken antihypertensive agents, nitrates, antiarrhythmic agents and antiplatelet agents. Non-DHP CCB initiators were also more likely to have had asthma and used bronchodilators or corticosteroids (table 1 and see online supplementary table S5a–S5e).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study cohort assembly. ACS, acute coronary syndromes; BBs, β blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. N and n represented number of patient episodes and number of patients remained and excluded in each step.

Table 1.

Selected baseline demographics, resource utilisation, comorbidities and medication use between cardioselective BB or bon-DHP CCB initiators*

| Before matching |

After matching |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total study cohort (n=22 985) |

1:1 Random-sample† matched cohort (n=7176) |

|||||

| Cardioselective BBs (n=18 406) | Non-DHP CCBs (n=4579) | STD | Cardioselective BBs (n=3588) | Non-DHP CCBs (n=3588) | STD | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 70.4 (9.9) | 73.8 (10.2) | −0.34 | 73.7 (10.2) | 73.5 (10.4) | 0.02 |

| Male, % | 59.6 | 55.4 | 0.09 | 56.1 | 55.7 | 0.01 |

| Length of stay of ACS hospitalisation, day, mean (SD) | 8.6 (7.9) | 10.5 (12.6) | −0.18 | 10.0 (11.4) | 10.2 (12.4) | −0.02 |

| COPD duration, day, mean (SD) | 998.1 (773.7) | 1374.0 (967.6) | −0.43 | 1384.4 (962.9) | 1367.2 (988.1) | 0.02 |

| Resource utilisation | ||||||

| Number of hospitalisation due to any episodes, mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.6 (1.0) | −0.25 | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 0.01 |

| Number of outpatient visits due to any episodes, mean (SD) | 8.2 (6.2) | 14.5 (9.6) | −0.78 | 14.0 (9.2) | 13.9 (9.4) | 0.02 |

| Number of outpatient visits due to CV episodes,‡ mean (SD) | 3.9 (4.3) | 5.2 (4.9) | −0.29 | 5.4 (4.8) | 5.3 (4.9) | 0.02 |

| Number of outpatient visits due to pulmonary-related episodes,§ mean (SD) | 1.2 (2.6) | 2.7 (3.9) | −0.44 | 2.0 (3.6) | 2.1 (3.2) | −0.01 |

| Number of drugs, mean (SD) | 14.4 (6.7) | 21.0 (9.4) | −0.81 | 20.4 (9.3) | 20.1 (9.0) | 0.03 |

| Comorbidities, % | ||||||

| Before the ACS admission date | ||||||

| MI | 17.3 | 17.1 | 0.01 | 18.3 | 17.5 | 0.02 |

| PTCA | 4.7 | 6.6 | −0.09 | 7.0 | 7.0 | <0.01 |

| Stent | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.04 | 2.6 | 2.8 | −0.01 |

| CABG | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.01 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 1.8 | 2.8 | −0.07 | 2.8 | 2.8 | <0.01 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 12.5 | 14.3 | −0.06 | 14.8 | 14.7 | <0.01 |

| TIA | 10.3 | 12.1 | −0.06 | 12.2 | 12.2 | <0.01 |

| Between the ACS admission date and the index date | ||||||

| MI | 76.3 | 58.2 | 0.40 | 62.2 | 62.8 | −0.01 |

| PTCA | 44.0 | 25.9 | 0.41 | 29.1 | 30.4 | −0.03 |

| Stent | 37.0 | 16.0 | 0.52 | 17.9 | 18.3 | −0.01 |

| CABG | 17.3 | 7.8 | 0.30 | 8.7 | 9.1 | −0.01 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 0.5 | 0.6 | −0.01 | 0.5 | 0.6 | −0.02 |

| Ischaemic stroke | 4.7 | 4.5 | 0.01 | 5.0 | 4.5 | 0.02 |

| TIA | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 2.0 | −0.02 |

| Before the index date | ||||||

| Hypertension | 82.0 | 81.0 | 0.03 | 83.0 | 82.3 | 0.02 |

| Angina | 52.1 | 62.8 | −0.22 | 60.7 | 59.8 | 0.02 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 86.1 | 84.2 | 0.06 | 84.9 | 84.5 | 0.01 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmia | 44.1 | 50.8 | −0.14 | 49.7 | 48.9 | 0.02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 19.1 | 25.7 | −0.17 | 25.4 | 24.4 | 0.02 |

| CHF | 45.3 | 53.7 | −0.18 | 53.8 | 53.7 | <0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 36.9 | 38.8 | −0.04 | 39.4 | 39.5 | <0.01 |

| PVD | 18.4 | 12.7 | 0.21 | 13.3 | 13.1 | 0.01 |

| Disorders of lipid metabolism | 65.5 | 52.9 | 0.27 | 56.9 | 56.1 | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 41.1 | 42.4 | −0.03 | 44.3 | 43.6 | 0.01 |

| Asthma | 23.3 | 40.5 | −0.40 | 37.0 | 35.9 | 0.02 |

| Medication use, % | ||||||

| Before the ACS admission date | ||||||

| ACEIs/ARBs/renin inhibitors | 51.6 | 56.5 | −0.10 | 58.2 | 57.6 | 0.01 |

| Non-cardioselective BBs | 19.0 | 32.2 | −0.37 | 33.9 | 32.7 | 0.03 |

| DHP CCBs | 35.4 | 46.0 | −0.24 | 47.5 | 47.1 | 0.01 |

| Diuretics | 44.8 | 56.0 | −0.23 | 56.2 | 55.3 | 0.02 |

| Other antihypertensive agents | 15.9 | 24.9 | −0.26 | 25.3 | 25.0 | 0.01 |

| Nitrates | 30.2 | 46.8 | −0.36 | 45.9 | 45.8 | <0.01 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 7.2 | 11.3 | −0.14 | 10.5 | 10.3 | <0.01 |

| Digoxin | 9.3 | 16.6 | −0.23 | 14.7 | 15.0 | −0.01 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 33.1 | 51.1 | −0.48 | 50.9 | 50.7 | 0.01 |

| Anticoagulants | 7.0 | 7.6 | −0.02 | 8.5 | 7.5 | 0.04 |

| Fibrates/statins | 37.2 | 32.8 | 0.10 | 35.7 | 35.1 | 0.01 |

| Between the ACS admission date and the index date | ||||||

| ACEIs ARBs/renin inhibitors | 48.5 | 36.2 | 0.26 | 41.9 | 40.3 | 0.03 |

| Non-cardioselective BBs | 4.2 | 8.7 | −0.23 | 9.2 | 8.7 | 0.02 |

| DHP CCBs | 11.6 | 8.8 | 0.10 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 0.01 |

| Diuretics | 27.1 | 29.4 | −0.05 | 30.9 | 30.0 | 0.02 |

| Other antihypertensive agents | 3.3 | 4.2 | −0.06 | 4.1 | 4.4 | −0.01 |

| Nitrates | 47.5 | 59.7 | −0.25 | 59.2 | 59.0 | <0.01 |

| Antiarrhythmic agents | 6.2 | 7.1 | −0.04 | 6.9 | 7.0 | <0.01 |

| Digoxin | 6.1 | 10.5 | −0.17 | 9.0 | 9.4 | −0.02 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 60.6 | 56.9 | 0.10 | 59.5 | 59.8 | −0.01 |

| Anticoagulants | 6.1 | 6.6 | −0.02 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 0.03 |

| Fibrates/statins | 48.2 | 25.6 | 0.51 | 29.4 | 29.4 | <0.01 |

| Before the index date | ||||||

| Antidiabetic agents | 27.1 | 27.2 | <0.01 | 29.4 | 29.3 | <0.01 |

| Short-acting bronchodilators | 34.3 | 49.8 | −0.32 | 45.7 | 44.2 | 0.03 |

| Long-acting bronchodilators | 19.6 | 27.7 | −0.21 | 24.9 | 23.6 | 0.03 |

| ICS | 23.8 | 34.3 | −0.25 | 30.8 | 29.6 | 0.03 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 44.6 | 64.4 | −0.45 | 61.4 | 61.4 | <0.01 |

| Oral bronchodilators | 25.8 | 61.7 | −1.16 | 57.0 | 56.7 | 0.01 |

*Presenting as summary estimates for mean, SD and STD across databases.

†One randomly sampled cardioselective BBs user: 1 non-DHP CCBs user in each matched subset.

‡CV episodes included: MI, coronary revascularisation (PTCA, stent, CABG), haemorrhagic stroke, ischaemic stroke, TIA, hypertension, angina, IHD, cardiac dysrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, CHF, cerebrovascular disease and PVD.

§Pulmonary-related episodes included COPD, asthma, pneumonia, influenza and acute bronchitis.

ACEIs, ACE inhibitors; ACS, acute coronary syndromes; ARBs, angiotensin II receptor blockers; BBs, β blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Cox, cyclooxygenase; CV, cardiovascular; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; IHD, ischaemia heart disease; MI, myocardial infarction; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PVD, peripheral vascular disease; STD, standardised differences; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

The PS-matched cohort included 11 479 cardioselective BB initiators and 3588 non-DHP CCB initiators (66% of the total study cohort). Most, but not all, covariates had standardised differences of <0.1 in the matched cohort with random sampling of comparator patients (table 1 and see online supplementary table S5a–S5e). Summaries of the PS distributions across study drugs and databases are provided in online supplementary table S6.

Follow-up and incidence rates

The mean follow-up duration ranged from 1.9 to 3.5 years across databases, with 7489 death, 4970 CV hospitalisation and 1829 COPD hospitalisation events. Incidence rates of individual outcomes for each treatment group are presented in table 2 and online supplementary table S7.

Table 2.

Follow-up and outcome event rates for cardioselective BB or non-DHP CCB initiators

| Cardioselective BBs (n=18 406) |

Non-DHP CCBs (n=4579) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database | Number of patients | Number of events | Follow-up person-years | Crude incidence (per 1000 person-years) | Number of patients | Number of events | Follow-up person-years | Crude incidence (per 1000 person-years) |

| All-cause mortality* | ||||||||

| US Optum | 6383 | 384 | 12 298 | 31.2 (28.3 to 34.5) | 296 | 35 | 445 | 78.7 (56.5 to 109.5) |

| US PACE | 3372 | 1909 | 11 616 | 164.3 (157.1 to 171.9) | 909 | 717 | 3301 | 217.2 (201.9 to 233.7) |

| US PAAD | 2108 | 957 | 6264 | 152.8 (143.4 to 162.8) | 560 | 353 | 2128 | 165.9 (149.4 to 184.1) |

| Italy RER | 2489 | 989 | 8042 | 123.0 (115.6 to 130.9) | 565 | 352 | 2181 | 161.4 (145.4 to 179.2) |

| Taiwan NHI | 4054 | 1003 | 11 403 | 88.0 (82.5 to 93.4) | 2249 | 790 | 6491 | 121.7 (113.2 to 130.2) |

| Summary estimate | 96.9 (61.9 to 151.8) | 145.0 (111.1 to 189.3) | ||||||

| CV hospitalisations* | ||||||||

| US Optum | 6383 | 476 | 11 534 | 41.3 (37.7 to 45.2) | 296 | 27 | 402 | 67.2 (46.1 to 97.9) |

| US PACE | 3372 | 1144 | 9155 | 125.0 (117.9 to 132.4) | 909 | 312 | 2582 | 120.9 (108.2 to 135.0) |

| US PAAD | 2108 | 633 | 4986 | 127.0 (117.4 to 137.2) | 560 | 169 | 1724 | 98.0 (84.3 to 114.0) |

| Italy RER | 2489 | 761 | 6267 | 121.4 (113.1 to 130.4) | 565 | 225 | 1608 | 139.9 (122.8 to 159.4) |

| Taiwan NHI | 4054 | 816 | 10 055 | 81.2 (75.6 to 86.7) | 2249 | 407 | 5763 | 70.3 (63.4 to 77.1) |

| Summary estimate | 91.7 (63.4 to 132.5) | 96.8 (72.1 to 129.9) | ||||||

| COPD hospitalisations* | ||||||||

| US Optum | 6383 | 192 | 12 035 | 15.95 (13.9 to 18.4) | 296 | 35 | 395 | 88.5 (63.6 to 123.3) |

| US PACE | 3372 | 274 | 11 023 | 24.9 (22.1 to 28.0) | 909 | 214 | 2808 | 76.2 (66.7 to 87.1) |

| US PAAD | 2108 | 155 | 5938 | 26.1 (22.3 to 30.6) | 560 | 146 | 1823 | 80.1 (68.1 to 94.2) |

| Italy RER | 2489 | 240 | 7529 | 31.9 (28.1 to 36.2) | 565 | 145 | 1804 | 80.4 (68.3 to 94.6) |

| Taiwan NHI | 4054 | 154 | 11 145 | 13.8 (11.6 to 16.0) | 2249 | 274 | 6022 | 45.5 (40.1 to 50.9) |

| Summary estimate | 21.5 (15.9 to 29.1) | 71.5 (54.6 to 93.6) | ||||||

BBs, β blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; NHI, National Health Insurance; PAAD, Pharmacy Assistance for the Aged and Disabled; PACE, Pharmacy Assistance Contract for the Elderly; RER, Emilia-Romagna Region.

*Based on the analysis that considered first exposure carried forward.

All-cause mortality and CV hospitalisations

In the primary analysis considering first exposure carried forward, the crude HRs comparing cardioselective BBs to non-DHP CCBs on all-cause mortality and CV hospitalisations were 0.73 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.83) and 0.98 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.14), respectively. After PS matching, the adjusted HRs were 0.90 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.02) for mortality and 1.06 (95% CI 0.91 to 1.23) for CV hospitalisations. We observed substantial statistical heterogeneity across databases, with HRs and 95% CIs for mortality below one in the PACE and RER databases. In the as-treated analysis, the adjusted HRs for mortality and CV hospitalisations were 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.96) and 1.07 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.36), respectively. We did not observe statistical heterogeneity for mortality, although the HR in the Taiwan NHI database was statistically significantly <1 (0.70; 95% CI 0.67 to 0.96) (table 3). HRs for CV hospitalisations due to acute MI, unstable angina and CHF were similar to those for the composite outcomes (see online supplementary table S8).

Table 3.

Risk of all-cause mortality, CV hospitalisations and COPD hospitalisations comparing cardioselective BB versus non-DHP CCB initiators

| Crude HR (95% CI) | HR after PS matching (95% CI) | Crude HR (95% CI) | HR after PS matching (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Database | First exposure carried forward |

As-treated analysis |

||

| All-cause mortality | ||||

| US Optum | 0.42 (0.30 to 0.60) | 1.05 (0.65 to 1.68) | 0.71 (0.31 to 1.61) | 1.23 (0.47 to 3.20) |

| US PACE | 0.76 (0.69 to 0.82) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98) | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.87) | 0.90 (0.64 to 1.27) |

| US PAAD | 0.91 (0.81 to 1.03) | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.36) | 0.94 (0.69 to 1.30) | 0.93 (0.58 to 1.52) |

| Italy RER | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.84) | 0.74 (0.64 to 0.85) | 0.86 (0.68 to 1.11) | 0.74 (0.52 to 1.05) |

| Taiwan NHI | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.78) | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.02) | 0.63 (0.51 to 0.78) | 0.70 (0.51 to 0.96) |

| Summary estimate | 0.73 (0.65 to 0.83) | 0.90 (0.78 to 1.02) | 0.75 (0.64 to 0.87) | 0.80 (0.67 to 0.96) |

| I2, % | 81.9 | 68.5 | 35.1 | 0.0 |

| P for heterogeneity | <0.001 | 0.013 | 0.187 | 0.649 |

| CV hospitalisations | ||||

| US Optum | 0.70 (0.47 to 1.02) | 0.96 (0.59 to 1.56) | 0.76 (0.41 to 1.39) | 0.84 (0.41 to 1.71) |

| US PACE | 1.01 (0.89 to 1.14) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.22) | 0.96 (0.81 to 1.13) | 1.09 (0.85 to 1.39) |

| US PAAD | 1.16 (0.97 to 1.37) | 1.30 (1.03 to 1.65) | 1.27 (0.97 to 1.67) | 1.41 (0.95 to 2.11) |

| Italy RER | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.93) | 0.86 (0.73 to 1.01) | 0.77 (0.59 to 0.99) | 0.75 (0.56 to 1.02) |

| Taiwan NHI | 1.12 (1.00 to 1.26) | 1.17 (1.00 to 1.36) | 1.06 (0.87 to 1.29) | 1.31 (1.00 to 1.71) |

| Summary estimate | 0.98 (0.84 to 1.14) | 1.06 (0.91 to 1.23) | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.15) | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.36) |

| I2, % | 78.2 | 63.8 | 51.0 | 59.5 |

| P for heterogeneity | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.086 | 0.043 |

| COPD hospitalisations | ||||

| US Optum | 0.19 (0.13 to 0.27) | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.87) | 0.16 (0.09 to 0.31) | 0.53 (0.19 to 1.47) |

| US PACE | 0.32 (0.27 to 0.39) | 0.51 (0.39 to 0.67) | 0.22 (0.17 to 0.29) | 0.54 (0.34 to 0.86) |

| US PAAD | 0.30 (0.24 to 0.38) | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.62) | 0.23 (0.15 to 0.34) | 0.54 (0.30 to 0.98) |

| Italy RER | 0.38 (0.31 to 0.48) | 0.56 (0.44 to 0.73) | 0.29 (0.19 to 0.46) | 0.40 (0.20 to 0.77) |

| Taiwan NHI | 0.30 (0.25 to 0.37) | 0.60 (0.47 to 0.78) | 0.24 (0.16 to 0.34) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.13) |

| Summary estimate | 0.30 (0.26 to 0.36) | 0.54 (0.47 to 0.61) | 0.23 (0.19 to 0.27) | 0.54 (0.41 to 0.70) |

| I2, % | 62.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| P for heterogeneity | 0.030 | 0.721 | 0.639 | 0.877 |

BBs, β blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; NHI, National Health Insurance; PAAD, Pharmacy Assistance for the Aged and Disabled; PACE, Pharmacy Assistance Contract for the Elderly; PS, propensity score; RER, Emilia-Romagna Region.

COPD hospitalisation outcome

In the first exposure carried forward and as-treated analyses, the crude HRs comparing cardioselective BBs to non-DHP CCBs for COPD hospitalisations were 0.30 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.36) and 0.23 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.27), respectively. After PS matching, HRs were still substantially <1: 0.54 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.61) for the first exposure carried forward analysis and 0.54 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.70) for the as-treated analysis (table 3). The adjusted HR for COPD hospitalisations restricted to the first 30 days of follow-up was 0.55 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.82) (table 4).

Table 4.

Results for 30-day COPD hospitalisations comparing cardioselective BB versus non-DHP CCB initiators*

| Database | Crude HR (95% CI) | HR after PS matching (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| US Optum | 0.28 (0.06 to 1.23) | 1.33 (0.17 to 10.70) |

| US PACE | 0.27 (0.15 to 0.47) | 0.70 (0.31 to 1.54) |

| US PAAD | 0.19 (0.09 to 0.37) | 0.43 (0.18 to 0.99) |

| Italy RER | 0.22 (0.10 to 0.48) | 0.37 (0.16 to 0.84) |

| Taiwan NHI | 0.28 (0.15 to 0.51) | 0.67 (0.32 to 1.38) |

| Summary estimate | 0.25 (0.18 to 0.34) | 0.55 (0.37 to 0.82) |

*Based on the analysis that considered first exposure carried forward.

BBs, β blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; NHI, National Health Insurance; PAAD, Pharmacy Assistance for the Aged and Disabled; PACE, Pharmacy Assistance Contract for the Elderly; PS, propensity score; RER, Emilia-Romagna Region.

Sensitivity and subgroup analyses

Sensitivity analyses applying a narrower PS caliper, asymmetric PS trimming, hd-PS matching and restricting to high-risk patients did not materially change the primary analysis results. The hd-PS sensitivity analysis yielded an estimate for COPD hospitalisations that was closest to the null at 0.62 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.76) (table 5). See online supplementary table S9a–S9c for baseline characteristics of patients in sensitivity analyses. The association of cardioselective BBs and each outcome was similar across periods before 2000, between 2001–2005 and after 2006 (see online supplementary table S10).

Table 5.

Results of sensitivity analyses comparing cardioselective BB versus non-DHP CCB initiators in three US databases*

| Type of analysis | Main analysis† | Sensitivity analysis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS matching caliper of 0.005 | Asymmetric PS trimming | hd-PS with additional 100 empirical covariates | Restricting to high-risk patients | ||

| Database | HR after PS matching (95% CI) |

||||

| All-cause mortality | |||||

| US Optum | 1.05 (0.65 to 1.68) | 1.06 (0.65 to 1.73) | 0.92 (0.54 to 1.56) | 1.02 (0.61 to 1.72) | 1.11 (0.53 to 2.33) |

| US PACE | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.98) | 0.85 (0.75 to 0.97) | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.97) | 0.86 (0.76 to 0.99) | 0.91 (0.73 to 1.14) |

| US PAAD | 1.12 (0.93 to 1.36) | 1.13 (0.93 to 1.36) | 1.00 (0.82 to 1.23) | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.40) | 1.02 (0.73 to 1.42) |

| Summary estimate | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.21) | 0.98 (0.78 to 1.23) | 0.90 (0.80 to 1.00) | 0.99 (0.78 to 1.26) | 0.95 (0.80 to 1.14) |

| CV hospitalisations | |||||

| US Optum | 0.96 (0.59 to 1.56) | 0.92 (0.56 to 1.49) | 0.81 (0.48 to 1.38) | 0.99 (0.60 to 1.65) | 0.70 (0.31 to 1.62) |

| US PACE | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.22) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.22) | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.23) | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.21) | 1.03 (0.76 to 1.39) |

| US PAAD | 1.30 (1.03 to 1.65) | 1.33 (1.04 to 1.69) | 1.31 (1.01 to 1.69) | 1.10 (0.86 to 1.43) | 1.31 (0.82 to 2.10) |

| Summary estimate | 1.11 (0.94 to 1.32) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.36) | 1.08 (0.87 to 1.35) | 1.04 (0.90 to 1.19) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.35) |

| COPD hospitalisations | |||||

| US Optum | 0.54 (0.37 to 0.87) | 0.59 (0.35 to 0.97) | 0.67 (0.37 to 1.23) | 0.77 (0.44 to 1.34) | 0.61 (0.30 to 1.22) |

| US PACE | 0.51 (0.39 to 0.67) | 0.52 (0.40 to 0.67) | 0.50 (0.37 to 0.66) | 0.61 (0.46–0.80) | 0.56 (0.39 to 0.81) |

| US PAAD | 0.45 (0.32 to 0.62) | 0.46 (0.33 to 0.64) | 0.36 (0.25 to 0.51) | 0.59 (0.41 to 0.84) | 0.52 (0.31 to 0.88) |

| Summary estimate | 0.50 (0.41 to 0.69) | 0.51 (0.42 to 0.61) | 0.47 (0.35 to 0.64) | 0.62 (0.51 to 0.76) | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.73) |

*Based on the analysis that considered first exposure carried forward.

†Main analysis used maximum PS matching caliper of 0.01, no PS trimming and a predefined PS model.

BBs, β blockers; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; DHP CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; hd, high dimensional; NHI, National Health Insurance; PAAD, Pharmacy Assistance for the Aged and Disabled; PACE, Pharmacy Assistance Contract for the Elderly; PS, propensity score; RER, Emilia-Romagna Region.

Discussion

This large-scale, multinational study employed state-of-the-art pharmacoepidemiologic methods, including an active comparator, new user cohort design, PS trimming and hd-PS matching, and found potential evidence of bias when comparing cardioselective BBs and non-DHP CCBs in patients with ACS and COPD as reflected by an apparent large protective effect of cardioselective BBs on a short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome. The observed association was highly consistent across different methods used to address confounding and across the five databases encompassing diverse populations from different health systems. Cardioselective BBs were not associated with reduced risk of mortality or CV hospitalisations, although statistical heterogeneity was observed across data sources.

While there may be several reasons for the apparent large protective effect of cardioselective BBs on a short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome, we believe bias due to unmeasured confounding is a major contributor. We cannot exclude the possibility that CCBs may worsen oxygenation and lead to an increased risk of COPD hospitalisations.46 47 However, this likely would not fully explain the observed association. In addition, this large finding is not likely to be due to chance given that we observed consistent point estimates across databases and statistical approaches and the CIs around the estimates were narrow. In expectation, if there is non-differential exposure or outcome misclassification, it would lead to bias towards the null and therefore it is unlikely to explain the observed findings. Moreover, our finding is unlikely to be explained by surveillance bias because healthcare professionals or patients themselves may be more attuned to respiratory-related effects when cardioselective BBs are given. Any resulting bias would be in the opposite direction of the observed association. It is possible that, since clinicians are more likely to prescribe CCBs than BBs to patients with more severe COPD, an anchoring bias48 could occur where CCB-treated patients may be more closely monitored for respiratory function and COPD exacerbations. However, our study outcomes were all defined by requiring hospitalisation, reducing the likelihood that such differential surveillance could fully explain the results. We did observe important differences between cardioselective BB and non-DHP CCB initiators at baseline. As compared to non-DHP CCB initiators, cardioselective BB initiators were younger, had less health resource utilisation and had less prior COPD medication use. While we were able to account for these differences in measured factors, we suspect that other important unmeasured risk factors for COPD hospitalisation remained imbalanced, such as differences in COPD severity and smoking status, which therefore led to a bias due to unmeasured confounding. However, since these variables are not captured in claims data, we cannot verify this.

In terms of pharmacological effects of BB treatment, animal models and meta-analyses of published randomised trials do not support the notion that BB treatment can have such a large and immediate effect on respiratory function.35–38 A prior study did not observe significant differences in pulmonary function or symptoms of wheezing or dyspnoea after acute administration of BB treatment in patients with cardiac disease and COPD.49 Our study, however, showed an apparent 45% reduction in COPD exacerbations comparing cardioselective BB to non-DHP CCB, which is similar to the 40% reduction observed in other observational studies in which BB use was compared to non-BB use.12 15 17 18 20 21 23 This apparent benefit associated with BB treatment is even considerably larger than that conferred by the most effective known treatment—long-acting bronchodilators—which reduce COPD hospitalisations by only 14–17%.50 51 An ongoing randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial is examining whether BB treatment can prevent COPD exacerbations.52 The results will help determine the extent to which the observed association between BB treatment and reduced COPD hospitalisation is due to actual clinical benefits of BBs versus bias in observational studies. Our study suggests the latter to be a major contributor.

A prior meta-analysis of observational studies suggested that BB use was associated with a 36% reduction in mortality in patients with coronary diseases and COPD.23 However, our PS-matched as-treated analysis of mortality yielded an HR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.96) and our PS-matched first exposure carried forward analysis yielded an HR of 0.90 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.02). Our results also suggested no benefit of cardioselective BBs on CV hospitalisations. These findings were similar to a recent population-based observational study that included 107 902 patients with COPD (only 3% of whom having concomitant MI diagnosis) and found no difference in CV hospitalisations (HR, 0.98 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.03)) and CV mortality (HR, 1.05 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.13)) between cardioselective BBs and non-DHP CCBs.53 An important difference between our study and most prior studies is that we used an active comparator group of non-DHP CCB initiators whereas most other studies compared BB users to non-users. To the best of our knowledge, only one published randomised trial has compared the efficacy of cardioselective BBs and non-DHP CCBs in patients with MI, who also had hypertension, and found similar results for mortality (HR, 1.01 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.16)) and MI (HR, 0.97 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.18)).54 Our mortality and CV hospitalisation results are in line with comparable bradycardic effects between cardioselctive BBs and non-DHP CCBs and are similar to those of the trial; however, given the potential unmeasured confounding observed for the short-term COPD hospitalisation outcome, our results are likely biased downward to the extent that COPD severity and smoking status, if imbalanced between treatment groups, are also risk factors for mortality and CV hospitalisations.5 55

A strength of our multinational study is that it permits examination of heterogeneity in results across databases and across countries. While the overall summary estimate did not indicate a survival benefit comparing cardioselective BBs to non-DHP CCBs, the database-specific HRs for mortality in the US PACE and Italy RER databases were 0.86 (95% CI 0.76 to 0.98) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.85), respectively. These findings are similar to those of some prior observational studies.14 16 While it is possible that this variation in results may be due to true heterogeneity in treatment effects across databases and populations, publication of these results in isolation could have led to very different and potentially misleading conclusions. The multidatabase approach protects against this potential problem. As prescribing patterns and patient characteristics vary across different health systems and geographical areas, true treatment effects and confounding can also vary across databases. Results can also vary across studies due to differences in design and analytic choices. In contrast to meta-analyses, which usually combine results from various study designs, our approach using a common protocol eliminates differences in design and analytic choices as an explanation for differences in results across databases.

Our study had several additional limitations. First, while we used a common protocol to implement our study across databases, the inherent variations in healthcare systems and data structures across countries necessitated certain database-specific modifications to the protocol. For example, some databases required different definitions for continuous enrolment and different coding methods for ascertainment of drug use. Also, we could only access information on inpatient diagnoses in the RER database, which likely resulted in the identification of a more severe COPD population than in the other databases. Moreover, information on drug days supply was not available in the RER database, which we inferred based on the defined daily dose. Second, as drug data during hospitalisation are usually not available in healthcare claims databases, we could not accurately capture inpatient drug information in all five databases. Also, patients may not fully adhere to their index drugs and may add or switch medications during follow-up. However, our first exposure carried forward and as-treated analyses yielded similar results, which partially mitigates concerns about exposure misclassification. Third, owing to analytic flexibility, we conducted sensitivity analyses in the three US databases only. However, results restricted to these three databases were similar to the main analyses, which also included the RER and Taiwan NHI databases. In addition to COPD severity and smoking status, we could not rule out the influence of unmeasured confounding from other clinical parameters, such as cardiac function. Finally, previous research suggests that non-DHP CCBs may increase the risk of CHF in patients experiencing acute MI,56 which may limit non-DHP CCBs as a comparison group.

In conclusion, this multinational study found a strong inverse association between cardioselective BB use and COPD hospitalisations, even in the first 30 days of follow-up, suggestive of bias likely due to unmeasured confounding. This apparent bias persisted across diverse populations and health systems and could not be fully removed by state-of-the-art design and analysis methods. This finding calls into question the validity of prior observational studies of the effectiveness of BBs and also the ability of claims data, in general, to address questions related to outcomes of BBs in COPD patients. Data from randomised trials are needed to elucidate the benefits and risks of BBs in patients with COPD.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-HD, MA, VM, C-HC, M-SL and JJG designed the study. VM, M-SL and JJG acquired data. Y-HD, MA, JL, ML and L-CW analysed data. Y-HD, MA, VM, C-HC, M-SL and JJG interpreted data. Y-HD and JJG drafted the manuscript. MA, VM, JL, ML, L-CW, C-HC and M-SL provided critical suggestion on the manuscript.

Funding: This study was in part supported by Taiwan National Science Council grant (103-2917-I-564-0-25), which did not play any role in the conception and design of study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Data retrieved from the Regional database of the Emilia-Romagna Region was provided through a collaborative agreement between the Regional Health Care and Social Agency, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, the Health Care Authority, Emilia-Romagna, Italy, and Thomas Jefferson University.

Competing interests: JJG was supported by a KL2/Catalyst Medical Research Investigator Training award (an appointed KL2 award) from Harvard Catalyst, The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award KL2 TR001100). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University, and its affiliated academic healthcare centres, or the National Institutes of Health. JJG was also previously Principal Investigator of grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation to the Brigham and Women's Hospital for work unrelated to this study and is a consultant to Aetion, a software company, and to Optum. All other authors declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Brigham and Women's Hospital, Thomas Jefferson University and the National Taiwan University Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases 2013. http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD_Report_2013_Feb20.pdf (accessed 5 Jul 2014).

- 2.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2008. http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2008/en/ (accessed 5 Jul 2014).

- 3.Sin DD, Man SFP. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circulation 2003;107:1514–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sidney S, Sorel M, Quesenberry CP Jr et al. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitalizations and mortality: Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program. Chest 2005;128:2068–75. 10.1378/chest.128.4.2068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Murray RP. Smoking and lung function of Lung Health Study participants after 11 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:675–9. 10.1164/rccm.2112096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reed RM, Eberlein M, Girgis RE et al. Coronary artery disease is under-diagnosed and under-treated in advanced lung disease. Am J Med 2012;125:1228.e13–.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P et al. Beta blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ 1999;318:1730–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottlieb SS, McCarter RJ, Vogel RA. Effect of beta-blockade on mortality among high-risk and low-risk patients after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998;339:489–97. 10.1056/NEJM199808203390801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bangalore S, Makani H, Radford M et al. Clinical outcomes with β-blockers for myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am J Med 2014;127:939–53. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SC Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO et al. , World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. Circulation 2011;124:2458–73. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318235eb4d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Woude HJ, Zaagsma J, Postma DS et al. Detrimental effects of beta-blockers in COPD: a concern for nonselective beta-blockers. Chest 2005;127:818–24. 10.1378/chest.127.3.818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stefan MS, Bannuru RR, Lessard D et al. The impact of COPD on management and outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: a 10-year retrospective observational study. Chest 2012;141:1441–8. 10.1378/chest.11-2032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quint JK, Herrett E, Bhaskaran K et al. Effect of β blockers on mortality after myocardial infarction in adults with COPD: population based cohort study of UK electronic healthcare records. BMJ 2013;347:f6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J, Radford MJ, Wang Y et al. Effectiveness of beta-blocker therapy after acute myocardial infarction in elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:1950–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angeloni E, Melina G, Roscitano A et al. β-blockers improve survival of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:525–31. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.07.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Gestel YR, Hoeks SE, Sin DD et al. Impact of cardioselective beta-blockers on mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:695–700. 10.1164/rccm.200803-384OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Short PM, Lipworth SI, Elder DH et al. Effect of beta blockers in treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2011;342:d2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutten FH, Zuithoff NP, Hak E et al. Beta-blockers May reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:880–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks TW, Creekmore FM, Young DC et al. Rates of hospitalizations and emergency department visits in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease taking beta-blockers. Pharmacotherapy 2007;27:684–90. 10.1592/phco.27.5.684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dransfield MT, Rowe SM, Johnson JE et al. Use of beta blockers and the risk of death in hospitalised patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2008;63:301–5. 10.1136/thx.2007.081893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL et al. β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD exacerbations. Thorax 2016;71:8–14. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Au DH, Bryson CL, Fan VS et al. Beta-blockers as single-agent therapy for hypertension and the risk of mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 2004;117:925–31. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.07.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du Q, Sun Y, Ding N et al. Beta-blockers reduced the risk of mortality and exacerbation in patients with COPD: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One 2014;9:e113048 10.1371/journal.pone.0113048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Stürmer T et al. Increasing levels of restriction in pharmacoepidemiologic database studies of elderly and comparison with randomized trial results. Med Care 2007;45:S131–142. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318070c08e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:915–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suissa S. Immortal time bias in observational studies of drug effects. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:241–9. 10.1002/pds.1357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Platt R, Carnahan RM, Brown JS et al. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Mini-Sentinel program: status and direction. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21(Suppl 1):1–8. 10.1002/pds.2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coloma PM, Schuemie MJ, Trifirò G et al. U-ADR Consortium. Combining electronic healthcare databases in Europe to allow for large-scale drug safety monitoring: the EU-ADR Project. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:1–11. 10.1002/pds.2053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen M, Bergman U, Choi NK et al. , AsPEN collaborators. The Asian Pharmacoepidemiology Network (AsPEN): promoting multi-national collaboration for pharmacoepidemiologic research in Asia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:700–4. 10.1002/pds.3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Non–ST-Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Executive Summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:2645–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.GAC Guideline Advisory Committee. ACS: unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation MI. 2008. http://www.gacguidelines.ca/site/GAC_Guidelines/assets/pdf/AMI07-ACS_-_Unstable_angina_Non-ST-Elevation_Mar_5_08_Final.pdf (accessed 5 Jul 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floyd JS, Blondon M, Moore KP et al. Validation of methods for assessing cardiovascular disease using electronic health data in a cohort of Veterans with diabetes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:467–71. 10.1002/pds.3921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DS, Donovan L, Austin PC et al. Comparison of coding of heart failure and comorbidities in administrative and clinical data for use in outcomes research. Med Care 2005;43:182–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein BD, Bautista A, Schumock GT et al. The validity of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes for identifying patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations. Chest 2012;141:87–93. 10.1378/chest.11-0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin R, Peng H, Nguyen LP et al. Changes in beta 2-adrenoceptor and other signaling proteins produced by chronic administration of ‘beta-blockers’ in a murine asthma model. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2008;21:115–24. 10.1016/j.pupt.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen LP, Omoluabi O, Parra S et al. Chronic exposure to beta-blockers attenuates inflammation and mucin content in a murine asthma model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;38:256–62. 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0279RC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ni Y, Shi G, Wan H. Use of cardioselective β-blockers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled, blinded trials. J Int Med Res 2012;40:2051–65. 10.1177/030006051204000602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardioselective beta-blockers in patients with reactive airway disease: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:715–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinnott SJ, Polinski JM, Byrne S et al. Measuring drug exposure: concordance between defined daily dose and days’ supply depended on drug class. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;69:107–13. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kent ST, Safford MM, Zhao H et al. Optimal use of available claims to identify a Medicare population free of coronary heart disease. Am J Epidemiol 2015;182:808–19. 10.1093/aje/kwv116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunelli SM, Gagne JJ, Huybrechts KF et al. Estimation using all available covariate information versus a fixed look-back window for dichotomous covariates. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;22:542–50. 10.1002/pds.3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Pharmacoepidemiology Toolbox. http://www.drugepi.org/dope-downloads/ (accessed 28 Feb 2015).

- 43.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P et al. Readers’ guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 2005;330:960–2. 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stürmer T, Rothman KJ, Avorn J et al. Treatment effects in the presence of unmeasured confounding: dealing with observations in the tails of the propensity score distribution—a simulation study. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:843–54. 10.1093/aje/kwq198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ et al. High-dimensional propensity score adjustment in studies of treatment effects using health care claims data. Epidemiology 2009;20:512–22. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a663cc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Melot C, Hallemans R, Naeije R et al. Deleterious effect of nifedipine on pulmonary gas exchange in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis 1984;130:612–6. 10.1164/arrd.1984.130.4.612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalra L, Bone MF. Effect of nifedipine on physiologic shunting and oxygenation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med 1993;94:419–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furnham A, Boo HC. A literature review of the anchoring effect. J Socio Econ 2011;40:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gold MR, Dec GW, Cocca-Spofford D et al. Esmolol and ventilatory function in cardiac patients with COPD. Chest 1991;100:1215–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B et al. ORCH investigators. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:775–89. 10.1056/NEJMoa063070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S et al. , UPLIFT Study Investigators. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:1543–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bhatt SP, Connett JE, Voelker H et al. β-Blockers for the prevention of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (βLOCK COPD): a randomised controlled study protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012292 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong YH, Chang CH, Wu LC et al. Use of cardioselective β-blockers and overall death and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with COPD: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2016;72:1265–73. 10.1007/s00228-016-2097-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bangalore S, Messerli FH, Cohen JD et al. , INVEST Investigators. Verapamil-sustained release-based treatment strategy is equivalent to atenolol-based treatment strategy at reducing cardiovascular events in patients with prior myocardial infarction: an INternational VErapamil SR-Trandolapril (INVEST) substudy. Am Heart J 2008;156:241–7. 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schünemann HJ, Dorn J, Grant BJ et al. Pulmonary function is a long-term predictor of mortality in the general population: 29-year follow-up of the Buffalo Health Study. Chest 2000;118:656–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldstein RE, Boccuzzi SJ, Cruess D et al. Diltiazem increases late-onset congestive heart failure in postinfarction patients with early reduction in ejection fraction. Circulation 1991;83:52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012997supp.pdf (2.1MB, pdf)