Abstract

Objectives

There was a large outbreak of measles in Liverpool, UK, in 2012–2013, despite measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) immunisation uptake rates that were higher than the national average. We estimated measles susceptibility of a cohort of children born in Liverpool between 1995 and 2012 to understand whether there was a change in susceptibility before and after the outbreak and to inform vaccination strategy.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The city of Liverpool, North West UK.

Participants

All children born in Liverpool (72 101) between 1995 and 2012 inclusive who were identified using the Child Health Information System (CHIS) and were still resident within Liverpool in 2014.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We estimated cohort age-disaggregated and neighbourhood-disaggregated measles susceptibility according to WHO thresholds before and after the outbreak for children aged 1–17 years.

Results

Susceptibility to measles was above WHO elimination thresholds before and after the measles outbreak in the 10+ age group. The proportion of children susceptible before and after outbreak, respectively: age 1–4 years 15.0% before and 14.9% after; age 5–9 years 9.9% before and 7.7% after; age 10+ years 8.6% before and 8.5% after. Despite an intensive MMR immunisation catch-up campaign after the 2012–2013 measles outbreak, the overall proportion of children with no MMR remains high at 6.1% (4390/72 351). Across all age groups and before and after the outbreak, measles susceptibility was clustered by neighbourhood, with deprived areas having the greatest proportion of susceptible children.

Conclusions

The risk of sustained measles outbreaks remains, especially as large pools of susceptible older children will start leaving secondary education and continue to aggregate in higher education, employment and other community settings and institutions resulting in the potential for a propagated measles outbreak.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY, PUBLIC HEALTH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a robust, prospectively collected data set comprising individual-level data on over 70 000 children over a period of 18 years.

This is a simple, repeatable and resource light data source and methodology assessing local area level susceptibility of vaccine preventable diseases that could be used by researchers, public health commissioners and policymakers across the UK.

We excluded infants too young for MMR1 at each time point as they were ineligible for measles, mumps and rubella vaccination, meaning that measles susceptibility may be underestimated.

We did not account for age–sex and geospatial mixing patterns that may influence the risk of measles susceptibility and infection.

Introduction

Measles is highly infectious, yet is preventable through the measles component of the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine. The measles vaccine was introduced in England in 1968 and led to an immediate reduction in cases of, and deaths attributed to, measles. MMR vaccination was introduced in the UK in 1988 as a single dose, with a second dose introduced in 1996.1 At present, in the UK, MMR is offered as a single dose at 13 months (MMR1) with the second dose offered at 40 months (MMR2).2 Routine monitoring data collected in England, COVER data3 have shown that by 1995, the uptake of a single dose of MMR reached a plateau at ∼92% within the UK at 2 years of age.

The prevention of spread of measles requires low levels of population susceptibility, most effectively achieved through a minimum of 95% uptake of second dose of MMR. In 1998, a paper claimed an alleged association between MMR and autism.4 The methods used and the alleged association were flawed, and widely criticised5 6 and the paper was subsequently discredited and retracted, with further studies showing no evidence of associations between MMR and either autism or bowel disease.7–10 However, the findings of this paper adversely affected MMR vaccination uptake across the UK, and MMR uptake remained below herd protection levels for several years.11

In 2012, the city of Liverpool had an estimated population of 469 690, and 83 344 (18%) were between the ages of 1 and 17 years.12 In Liverpool, MMR1 uptake at 2 years of age was 89.2% in 1997–1998 and this declined to 79.2% in 2003–2004, but subsequently improved to 96.0% in 2012–2013.11 The uptake of MMR2 at 5 years of age was 67.7% in 1999–2000 when records began, and dropped to 61.7% in 2003–2004, before increasing to 91.5% in 2012–2013. Liverpool has had above national average uptake for MMR1 for over a decade,11 but this was still below the 95% level required for herd protection, and high uptake in all neighbourhoods has not been achieved consistently.13

In 2012, there was a large outbreak of measles, initially concentrated in the Liverpool area, which subsequently spread to surrounding communities in the North West of England.14 Most cases occurred in older unvaccinated children, or infants too young for vaccination. During the outbreak, there were 651 laboratory-confirmed cases, of which 202 (31%) were born between 1995 and 2010.15

Population susceptibility to measles is dependent on the uptake of MMR1 and MMR2, vaccine effectiveness, immunity as a result of prior infection and protection by maternal antibodies in infants. Therefore, using these factors, it is possible to estimate population susceptibility to measles using a well-defined formula.16

We set out to estimate population susceptibility by cohort of eligible children for MMR vaccination before and after a large measles outbreak, using robust individual-level immunisation records from the Liverpool Child Health Information System (CHIS).17

Methods

We used the CHIS data to undertake a retrospective cohort study.

Study population

We established a birth cohort of children that were born in Liverpool between 1 January 1995 and 31 December 2012 and were still resident in the city in 2014. We included all children that were at least 13 months of age and so were eligible for MMR1. We excluded children under the age of 13 months as they were not eligible for MMR vaccination in the UK.18 The full vaccination history of those included was recorded prospectively through CHIS.17 In the UK, the CHIS data set holds a unique record for each child born in a defined geographical area up to the age of 18 years. Data from the CHIS are used for a variety of child health services, including immunisation services. We used codes within the CHIS that allowed us to exclude stillbirths, children who were born in the city but subsequently moved away and children who were born outside but moved into the city. The records include late vaccinations.

Uptake of MMR

We extracted pseudoanonymised data from CHIS, including: unique identifier; year and month of birth; year and month of MMR1 vaccination; year and month of MMR2 vaccination; and neighbourhood of residence based on lower super output area.19

Population susceptibility to measles

WHO has set maximum guideline thresholds for population susceptibility to measles based on age-structured mixing models that are required to achieve elimination of measles from the European region. Population susceptibility thresholds are based on age groups, with maximum susceptibility thresholds being 15% in those aged 1–4 years, 10% in those aged 5–9 years and 5% in those aged over 10 years.20

Statistical analysis

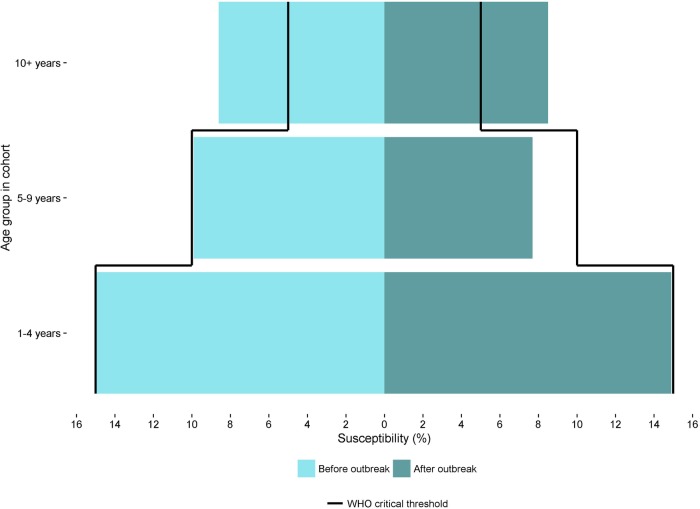

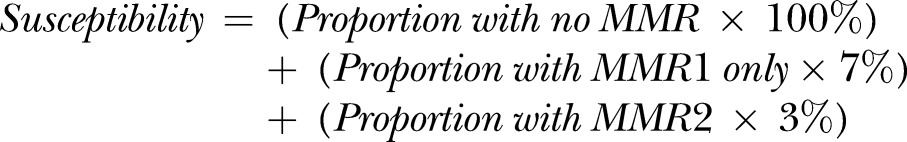

To estimate annual birth cohort susceptibility to measles before and after the outbreak, we calculated the number of children who had not received MMR, those who had received MMR1 only and those who had received MMR1 and MMR2 at two defined points in time: 31 December 2011 for the preoutbreak calculations and 31 December 2013 for the postoutbreak calculations. To estimate population susceptibility, we used a formula previously published based on WHO thresholds.16

|

We assumed vaccine efficacy to be 93% and 97% for the measles components of MMR1 and MMR2, respectively.21 Although data were pseudoanonymised, we knew from earlier work22 that confirmed cases were most likely not to have been vaccinated. Therefore, using birth year and age of cases, we classified these children as insusceptible for the calculation. Susceptibility was calculated first by birth year and then by age groups for comparability with WHO guideline thresholds. We additionally estimated susceptibility at the neighbourhood level before and after the outbreak, and plotted on neighbourhood maps. All data handling and statistical analyses were performed using R V.3.1.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 62 689 children were born and remained resident in Liverpool between 1995 and 2010. Using historical case management records, we identified 10 laboratory-confirmed cases from prior to the outbreak cohort.

A total of 72 351 children were born and remained resident in Liverpool between 1995 and 2012. In addition to the 10 cases that were laboratory-confirmed before the outbreak, there were a further 240 laboratory-confirmed cases reported during the outbreak.

Preoutbreak population measles susceptibility

At 31 December 2011, 1 month before the outbreak began, and including children born between 1995 and 2010, there were 4289 (6.8%) eligible children with no MMR, 16 907 (27.0%) children with MMR1 only and 41 483 (66.2%) children who had received MMR1 and MMR2. Across the population, susceptibility by birth year ranged from 7.0% for children born in 1995 to 27.9% for children born in 2010 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Susceptibility preoutbreak and postoutbreak by birth year, estimated using Child Health Information System data.

In relation to figure 2 which presents susceptibility by age group, preoutbreak susceptibility to measles was above the WHO susceptibility threshold for children in the 10+ years age group, at 8.6% (3.6% above the WHO threshold). Susceptibility was 15% (at the WHO threshold) for children born aged 1–4 years, and was 9.9% (0.1% below the WHO threshold) for children aged 5–9 years. Additionally, when looking at individual birth years, susceptibility was above the WHO thresholds in those born in years between 1995 and 2003 (figure 1).

Figure 2.

Susceptibility preoutbreak and postoutbreak by age groups, estimated using the Child Health Information System.

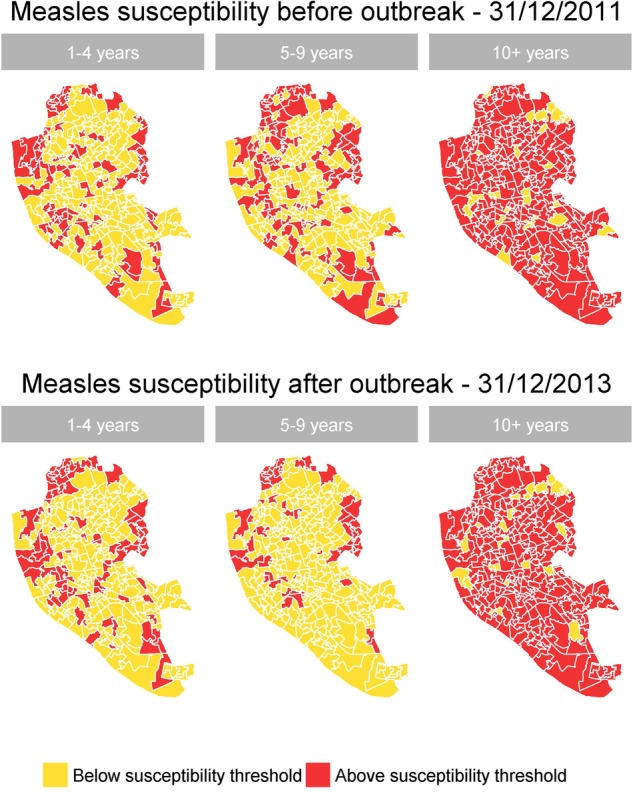

When we estimated susceptibility to measles by neighbourhood of residence, preoutbreak population susceptibility was above the threshold in: 267/291 (92%) in the 10+ age group; 97/291 (33%) neighbourhoods in the 1–4 years age group and 110/291 (38%) neighbourhoods in the 5–9 years age group (figure 3 and table 1).

Figure 3.

Measles susceptibility in Liverpool preoutbreak and postoutbreak by age groups and neighbourhood, estimated using Child Health Information System data.

Table 1.

Number and percentage of neighbourhoods above WHO measles susceptibility thresholds by age group (n=291), estimated using the Child Health Information System

| Age groups | Preoutbreak (%) | Postoutbreak (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1–4 | 97 (33.3) | 92 (31.6) |

| 5–9 | 110 (37.8) | 57 (19.6) |

| 10+ | 267 (91.8) | 269 (92.4) |

Postoutbreak population measles susceptibility

After the outbreak, there were 4390 (6.1%) children with no MMR, 18 027 (25.0%) children with MMR1 only and 49 684 (68.9%) children with MMR1 and MMR2. Across this eligible population, susceptibility by birth year ranged from 6.4% for those born in 2008 to 28.4% for those born in 2012 (figure 1).

In relation to figure 2, postoutbreak susceptibility remained above the WHO susceptibility threshold among children in the 10+ years age group at 8.5% (3.5% above the WHO threshold). Susceptibility was 14.9% (0.1% below the WHO threshold) for children aged 1–4 years and 7.7% (2.3% below the WHO threshold) for children aged 5–9 years. When examining individual, birth year's susceptibility remained above WHO thresholds for those born in years between 1995 and 2003 (figure 1).

By neighbourhood of residence, postoutbreak population susceptibility to measles was above the susceptibility threshold in: 269/291 (92%) neighbourhoods for children aged 10 years and older; in 92/291 (32%) neighbourhoods for children aged 1–4 years and in 57/291 (20%) neighbourhoods for children aged 5–9 years (figure 3 and table 1).

Changes in MMR vaccine uptake preoutbreak and postoutbreak

Before and after the outbreak period, the percentage of children with no MMR decreased from 6.8% (4289/62 689) to 6.1% (4390/72 351), the percentage of children with MMR1 only decreased from 27.0% (16 907/62 689) to 25.0% (18 027/72 351) and the percentage of children with MMR1 and MMR2 increased from 66.2% (41 483/62 689) to 68.7% (49 684/72 351).

Discussion

Historically and in comparison to the England and Wales average, Liverpool had high uptake of MMR vaccination; however, evidence from vaccination records demonstrated that there was a substantial pool of susceptible children to sustain an outbreak that affected the city and surrounding areas in 2012. Despite intensified vaccination campaigns during and following the outbreak, the pool of susceptible children remains above WHO susceptibility threshold, that is, large enough to sustain future measles outbreaks, especially among older children.

During the outbreak, there were 651 confirmed cases, of which 281 (43%) were born between 1995 and 2010 inclusive. Some of the additional vaccinations that were administered during 2012–2013 include: postexposure prophylaxis; and for those younger eligible and unexposed children, part of routine immunisations. These additional vaccination campaigns reduced population susceptibility for birth year cohorts and neighbourhoods, but it was inadequate to provide population protection. Catch-up campaigns have been more successful with children who had already received one dose of MMR and were therefore already engaged with vaccination services. Campaigns were less successful, however, with those children who had no MMR; and particularly children over the age of 9 years. Although NICE guidance on reducing the differences in immunisation uptake has highlighted the need for prioritising vaccination for deprived populations,23 a recent study in Liverpool has shown that children from most deprived neighbourhoods are still least likely to receive MMR vaccination.13 This also mirrors findings from the present study, where susceptibility was clustered by neighbourhood in the younger age groups, predominantly in the deprived neighbourhoods of the city.

The main susceptible age group remains those aged 10 years and over, particularly those born between 2000 and 2003. One possible explanation for this is the historically lower rates of MMR uptake in this age group as a consequence of the 1998 MMR scare, and we hypothesise that this group has not been effectively reached by catch-up campaigns. Older children are particularly vulnerable to measles as they move from childhood to young adulthood and mix with new groups in different congregate environments. According to the UK Department of Education, over 90% of children over the age of 16 years transited into further education and ∼65% of those over the age 19 transited into further educational studies.24 If the susceptibility pattern we uncovered in this study is repeated across the country, then it is possible that we are entering a period where large pools of measles-susceptible individuals are entering further education settings where social mixing patterns may be intense, and with high potential for generating and sustaining measles outbreaks. Indeed, at the time of writing (August 2016), there are already cases of measles in teenagers and young people linked to music festivals in the UK where this age group is predominant and mixing patterns are intense.25 26 Moreover, children from this age group who go on to enter employment in educational or healthcare settings may mix with highly vulnerable infants too young to be vaccinated.

The CHIS data contain individual-level records and vaccination status of all children residing within the city. Therefore, with targeted vaccination campaigns specifically aimed at groups and neighbourhoods where susceptibility is highest, it is possible to mitigate the risk of future measles outbreaks among populations with the greatest susceptibility. Work with local NHS and public health services to implement this approach is currently in progress.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study has a number of strengths including the use of a robust, prospectively collected data set comprising of individual-level data of over 70 000 children over a period of 18 years. This allowed us to estimate measles susceptibility before and after a large outbreak. Furthermore, the study design uses a simple, repeatable and resource light data source and methodology for estimating local area level susceptibility of vaccine preventable diseases that could be used by researchers, public health commissioners and policymakers across the UK.

However, we excluded infants too young for MMR1 under 13 months of age at each time point as they were not eligible to receive MMR vaccination (∼5000 in total). It is acknowledged that maternal antibodies provide measles protection, but this wanes during the first year of life. Therefore, it is possible that some of these infants, particularly those over the age of 6 months, may be susceptible.27 Further modelling could estimate the effect of including these infants, in addition to expanding analysis to account for age–sex and geospatial mixing patterns.16 Although immunisation data held by CHIS are more up to date and timely than COVER data, there may be delays in the reporting of information from GP practices to CHIS; however, this is unlikely to be significant to impact on WHO susceptibility thresholds for this analysis.

Implications for policymakers/immunisation commissioners

Responding to measles outbreaks is extremely challenging and costly for health services. The total cost of the Liverpool measles outbreak was estimated to be £4.4 million, whereas the cost of providing all missing MMR vaccinations over the 5 years prior to the outbreak would have been ∼4% of the cost of the outbreak.28 Therefore, commissioners and policymakers need to urgently consider the need for robust and well-resourced vaccination programmes to improve vaccination uptake rates in order to consistently achieve herd protection across all settings and population groups.

Conclusions

Using robust vaccination records for children born between 1995 and 2012, we have established that population susceptibility to measles remains high and has only diminished slightly since the outbreak. Therefore, this cohort remains vulnerable to future outbreaks of measles. Susceptible children and young adults who are now beginning to enter higher and further education and the workplace are vulnerable to contracting and spreading measles infection. Therefore, further public health measures such as targeted and timely catch-up vaccination campaigns to reduce the level of susceptible population are needed if we are going to prevent future measles outbreaks.

Recommendations

Catch-up campaigns in local areas, such as Liverpool, aimed towards young adults entering higher and further education establishments are required as a matter of urgency. This could be combined with existing routine higher education vaccination campaigns such as vaccination against meningococcal disease. For those young adults who neither engage in further/higher education, nor enter employment, a catch-up campaign before leaving school needs to be considered.

Following the catch-up campaigns, and in order to maintain improved uptake rates, there is a need for a robust system in schools (school entry and school leaving immunisation checks) to be established and strengthened.

Footnotes

Contributors: The study was designed and implemented by AK, with support and input from DH, PM and SG. AK, DH and PM undertook the analysis, and all coauthors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. PM was supported by The Farr Institute for Health Informatics Research (MRC grant: MR/M0501633/1).

Competing interests: AK, SG and RV are all directly employed by Public Health England; PM and DH have honorary contracts with Public Health England.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not required as this was undertaken as part of outbreak investigation and management, and personal identifiable data were not used.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data were accessed through Liverpool Child Health Information System (CHIS) with agreement from Liverpool Community Health NHS Trust.

References

- 1.Health Protection Agency. Health Protection Agency Health Protection Agency, 2010. (cited 11 March 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.GOV.UK. NHS Choices. (cited 6 October 2015). http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vaccinations/pages/vaccination-schedule-age-checklist.aspx

- 3.GOV.UK. Research and Analysis 2015. (cited 6 October 2015). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/cover-of-vaccination-evaluated-rapidly-cover-programme-annual-data

- 4.Wakefield A, Murch SH, Anthony A et al. . Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. Lancet 1998;351:637–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen RT, De Stefano F. Vaccine adverse events: causal or coincidental? Lancet 1998;351:611–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78423-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicoll A, Elliman D, Ross E. MMR vaccination and autism 1998. Lancet 1998;316:715–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bower M. MMR vaccine policy is backed. BMJ 1998;316:955 10.1136/bmj.316.7136.955a9550949 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Metcalf J. Is measles infection associated with Crohn's disease? BMJ 1998;316:166 10.1136/bmj.316.7126.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fombonne E. Inflammatory bowel disease and autism. Lancet 1998;351:166 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60608-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Editors of The Lancet. Retraction—ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive development disorder in children. Lancet 2010;375:445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.HPA. HPA—Vaccine coverage and COVER. (cited 28 March 2013). http://www.hpa.org.uk/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/VaccineCoverageAndCOVER/

- 12.Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics. (cited 8 February 2016). http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/population-estimates-for-uk--england-and-wales--scotland-and-northern-ireland/mid-2011-and-mid-2012/stb---mid-2011---mid-2012-uk-population-estimates.html

- 13.Hungerford D, MacPherson P, Farmer S et al. . Effect of socioeconomic deprivation on uptake of measles, mumps and rubella vaccination in Liverpool, UK over 16 years: a longitudinal ecological study. Epidemiol Infect 2016;144:1201–11. 10.1017/S0950268815002599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vivancos R, Keenan A, Farmer S et al. . An ongoing large measles outbreak of measles in Merseyside, England, January to June 2012. Eurosurveillance 2012;17:pii: 20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vivancos R. Merseyside Measles Outbreak Report January 2012 to September 2013 2014. Internal Report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gay NJ. The theory of measles elimination: implications for the design of elimination strategies. J Infect Dis 2004;189:S27–35. 10.1086/381592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health. Public health functions to be exercised by NHS England 2013. (cited 8 February 2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/192979/28_CHIS_service_specification_VARIATION_130422.pdf

- 18.World Health Organization. The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series. Module 7: Measles Update 2009 2009. (cited 22 July 2016). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44038/1/9789241597555_eng.pdf

- 19.Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics Super Output Area (SOA) 2016. (cited 22 June 2016). http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160129193951/http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/geography/beginner-s-guide/census/super-output-areas--soas-/index.html

- 20.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Measles. A Strategic Framework for the Elimination of measles in the European Region 1999. (cited 20 June 2016). http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/119802/E68405.pdf

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014. (cited 8 February 2016). http://www.cdc.gov/measles/vaccination.html

- 22.Hungerford D, Cleary P, Ghebrehewet S et al. . Risk factors for transmission of measles during an outbreak: matched case-control study. J Hosp Infect 2014;86:138–43. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Immunisations: reducing differences in under 19s 2009. (cited 3 August 2016). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph21/resources/immunisations-reducing-differences-in-uptake-in-under-19s-1996231968709

- 24.Department for Education. Destinations of key stage 4 and key stage 5 students in state-funded and independent institutions, England, 2013/14 2016. (cited 5 July 2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/493181/SFR052016_Text.pdf

- 25.GOV.UK. News Story: Measles Vaccination advice for young people 2016. (cited 8 August 2016). https://www.gov.uk/government/news/measles-vaccination-advice-for-young-adults

- 26.le Polain de Waroux O, Saliba V, Cottrell S et al. . Summer music and arts festivals as hot spots for measles transmission: experience from England and Wales, June to October 2016. Euro Surveill 2016;21:pii: 30390 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.44.30390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manikkavasagan G, Ramsay M. Protecting infants against measles in England and Wales: a review. Arch Dis Child 2009;94:681–5. 10.1136/adc.2008.149880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghebrehewet S, Thorrington D, Farmer S et al. . The economic cost of measles: healthcare, public health and societal costs of the 2012–13 outbreak in Merseyside, UK. Vaccine 2016;34:1823–31. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]