Abstract

Objectives

Despite the possibility of early detection of cervical cancer, participation in screening programmes among young Koreans is low. We sought to identify associations between risk factors and participation in screening for cervical cancer among young Koreans.

Design

Nationwide cross-sectional study.

Setting

Republic of Korea.

Participants

3734.

Main outcome measures

The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V: 2010–2012) was used to evaluate factors associated with attendance for cervical cancer screening among women aged 15–39. After excluding those who were previously diagnosed with cervical cancer and those with incomplete responses to questionnaires, a total of 3734 subjects were eligible. Multi-dimensional covariates as potential predictors of cervical cancer screening were adjusted in multiple logistic regression analysis.

Results

The participation rate for cervical cancer screening was 46% among women aged 40 or younger. The logistic analyses showed that age, education, total household income, smoking and job status among women aged 15–39 were associated with participation in cervical cancer screening (p<0.05). After age stratification, the associated factors differed by age groups. Moreover, a dose–response between participation in cervical cancer screening and high total household income in the 30–39 age group was seen.

Conclusions

Predictive factors differed among young women (aged 15–29 vs 30–39). Thus, age-specific tailored interventions and policies are needed to increase the participation rate in screening for cervical cancer.

Keywords: Screening, Risk factors, KNHANES V, Cervical cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study results are based on a large representative sample, reducing the possibility of selection bias.

Predictors for cervical cancer screening were estimated in a multi-dimensional structure.

Because the information was derived from self-reported health surveys, information bias, such as acquiescence bias or recall bias, cannot be ruled out.

Introduction

Despite trends of decreasing incidence and mortality from cervical cancer, it remains a major health issue. Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide, resulting in around 528 000 incident cases and 266 000 deaths in 2012.1 In Korea, more than 3584 new cervical cancer cases (age-standardised incidence, 9.5 per 100 000 persons) were diagnosed in 2012, accounting for 3.2% of all new female cancer cases.2

Screening programmes help in early detection of cervical cancer, contributing to decreases in both the incidence and mortality of the disease.3 Since 1988, the Korean government has conducted population-based cervical cancer screening. The Korea National Health Insurance (NHI) programme initially provided this service to employees and their lineal ascendants and descendants. As part of a 10-year plan for cancer management, the National Cancer Screening Programme (NCSP) for Medical Aid Programme (MAP) receivers was introduced in 1999.4 Currently, there are two organised cancer screening programmes in Korea.4 5 One is NCSP, whose target population includes MAP receivers and NHI beneficiaries in the lower 50% income bracket, and the other is the NHI Cancer Screening Programme (NHICSP), whose target population includes those in the upper 50% income bracket.4 5 These two programmes together provide free cervical cancer screening to all Korean women aged 30 and over (since 2016, women aged 20–29 have been included in the cervical cancer screening programme) biennially by Papanicolaou (Pap) smear test.4 5

Despite evidence that the government's NCSP and NHICSP can reduce the mortality from cervical cancer, participation in Korea is much lower than in Western countries.6–8 Participation for cervical cancer screening is relatively low in women aged 40 or less, despite these women being a potential risk group for cervical cancer. To promote cervical cancer screening, an effort to increase the participation rate of the younger generations is necessary. Thus, it is important to understand potential barriers to participation in young women. Although the Pap smear is a preventive test, women rarely feel comfortable with it because they have to expose their genitalia to a healthcare provider, which is especially problematic if the doctor is male.9 In addition, several studies have reported that a woman's decision to seek a cervical cytology examination is negatively affected by fear and embarrassment of the procedures and test results. Negative emotions, such as shame, embarrassment and discomfort with a male doctor, are among the obstacles hindering cervical cytology examinations in eligible women.9–11

Some countries, including Korea, have reported increasing rates of cervical cancer in women under the age of 30 years.12–14 The risk factors are associated with their level of sexual activity.13 A worldwide study reported that because of later marriage, more men and women have premarital sex, and they often have multiple sexual partners.13 15 In addition, rapid cultural changes have affected sexual and social activities in Korea.8 For example, the age of first sexual intercourse is decreasing in Korea.13 16 These changes may influence the risk of developing cervical cancer and may help to explain the increasing incidence of cervical cancer in young women over the last two decades. Thus, efforts should be made to increase participation in screening among women in their 20s.

However, few studies have investigated individual and environmental factors that predict participation in screening for cervical cancer.5 17 Two previous studies were of limited usefulness because they did not include women younger than 30 years. Thus, we examined the participation rate in cervical cancer screening and identified associations between participation and relevant risk factors for cervical cancer among a young Korean population using data from the Fifth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES V, 2010–2012).

Methods

Data sources and study subjects

The Health Interview Survey sub-dataset, derived from the publicly available KNHANES V (2010–2012), was used. KNHANES is a nationwide cross-sectional survey conducted by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare. A stratified multistage clustered probability design is used to select representative samples of non-institutionalised Korean civilians for KNHANES, and the survey is performed periodically to assess the health and nutritional status of Koreans. The sampling framework for the subjects was derived from the 2005 Population and Housing Survey. Details of the survey have been published elsewhere.18–20

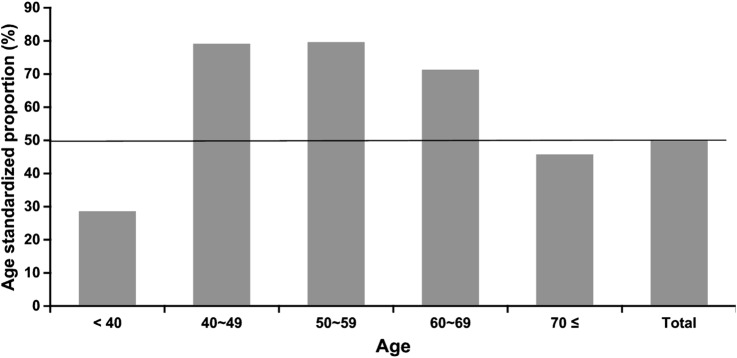

The raw data for KNHANES are publicly available on the KNHANES website.18 In total, 25 534 individuals participated in the health examination surveys between 2010 and 2012, and the response rates were 81.9%, 80.4% and 80.0% in 2010, 2011 and 2012, respectively. For our study, 1361 women were excluded due to incomplete responses regarding cervical cancer screening, weight or height. Men (n=10 875), women aged ≥40 and girls aged <15 years were also excluded (n=9564). Finally, 3734 women were eligible for inclusion in this study. The prevalence of cervical cancer screening was estimated in a total of 13 298 Korean women (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age-standardised proportion for participation in cervical cancer screening.

Definition of cervical cancer screening

Study participants were asked the question, ‘When was the last time you had a cervical cancer screening examination?’ The possible responses were ‘never’, ‘<1 year’, ‘1–2 years’ and ‘more than 2 years.’ Cervical cancer screening was assessed using a structured questionnaire.18–20 According to the guidelines of the NCSP, those who had undergone screening, including a Pap smear, within 2 years were defined as the participation group.

Demographic and socioeconomic factors

Participants were divided into two age groups: 15–29 and 30–39 years. The level of education was classified into four categories: elementary school or less (6 years' schooling or less), middle school (6–9), high school (9–12), and college or higher (12 or more years). Household income was grouped into four quartiles (low, middle-low, middle-high and high). Household income was estimated according to the equalised gross household income per month (household income divided by the number of individuals in the family) for each year.18–20 Current employment status (yes/no) was also evaluated. Other variables included age, body mass index (BMI) and age at menarche.

Health behaviours

The following health behaviours were assessed: alcohol consumption (less than/more than once per month in the past year), current smoking status (current smokers, ex-smokers, never smokers).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SAS software (V.9.4; SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) to evaluate the results of the multi-level stratified questionnaire with survey weights. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. The age-standardised proportion of the women participating in screening for cervical cancer in Korea was estimated using direct standardisation methods and the reference population of the 2005 Korean Population Census. For demographic features, categorical variables were described by sample count, estimated population, estimated percentages (%) and estimated standard error (SE) using the survey analysis tools in SAS (SAS syntax as ‘proc SURVEYFREQ’ and ‘proc SURVEYMEANS’).

Simple logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between cervical cancer screening and independent variables. Those factors identified as statistically significant by univariate analysis (p<0.05) were included as independent variables in multiple logistic regression analysis (SAS syntax as ‘proc SURVEYLOGIST’). The survey data are publicly available.

Results

General characteristics of the study subjects are presented in table 1. The mean age at menarche of the study population was 13.6 years and BMI was 21.9 kg/m² in the 15–39 age groups. Over 46% of the study population had participated in the cervical cancer screening programme. Those aged 30–39 years (n=1464, 73.3%) were more likely to have been screened than those aged 15–29 years (n=266, 15.3%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of young Korean females (aged 15–39)

| Age groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–29 |

30–39 |

Total |

||||

| N (%) (mean) |

Weighted no (SE) | N (%) (mean) |

Weighted no (SE) |

N (%) (mean) |

Weighted no (SE) | |

| Age | (22.3) | (0.1) | (34.6) | (0.1) | (27.8) | (0.2) |

| 15–29 | 1737 | 2 660 008 | 1737 (46.5%) | 2 660 008 | ||

| 30–39 | 1997 | 2 142 747 | 1997 (53.5%) | 2 142 747 | ||

| Menarche age | (13.6) | (0.3) | (13.7) | (0.1) | (13.6) | (0.1) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | (21.4) | (0.1) | (22.6) | (0.1) | (21.9) | (0.1) |

| Education levels | ||||||

| <6 | 60 (3.5%) | 78 811 | 10 (0.5%) | 17 925 | 70 (2.0%) | 96 736 |

| 6–9 | 367 (21.7%) | 571 868 | 25 (1.3%) | 38 998 | 392 (10.7%) | 610 866 |

| 10–12 | 643 (37.9%) | 1 029 906 | 766 (39.2%) | 884 053 | 1409 (38.6%) | 1 913 959 |

| >12 | 625 (36.9%) | 912 657 | 1152 (59.0%) | 1 137 606 | 1777 (48.7%) | 2 050 263 |

| Total household income | ||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 172 (10.0%) | 314 580 | 103 (5.2%) | 143 533 | 275 (7.5%) | 458 113 |

| 2Q | 434 (25.4%) | 719 372 | 558 (28.3%) | 647 924 | 992 (26.9%) | 1 367 296 |

| 3Q | 528 (30.8%) | 780 705 | 748 (37.9%) | 780 036 | 1276 (34.6%) | 1 560 740 |

| 4Q (highest) | 579 (33.8%) | 801 415 | 564 (28.6%) | 540 223 | 1143 (31.0%) | 1 341 638 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | 1453 (83.6%) | 2 180 333 | 1669 (83.6%) | 1 732 637 | 3122 (83.6%) | 3 912 970 |

| Ex-smoker | 116 (6.7%) | 192 018 | 168 (8.4%) | 196 330 | 284 (7.6%) | 388 347 |

| Current-smoker | 168 (9.7%) | 287 657 | 160 (8.0%) | 213 781 | 328 (8.8%) | 501 438 |

| Alcohol consumption (per month) | ||||||

| 1 or less | 975 (56.1%) | 1 466 194 | 1059 (53.0%) | 1 111 771 | 2034 (54.5%) | 2 577 965 |

| 1 or more | 762 (43.9%) | 1 193 814 | 938 (47.0%) | 1 030 976 | 1700 (45.5%) | 2 224 790 |

| Current job | ||||||

| No | 980 (56.4%) | 1 489 081 | 1096 (54.9%) | 1 161 981 | 2076 (55.6%) | 2 651 062 |

| Yes | 757 (43.6%) | 1 170 927 | 901 (45.1%) | 980 766 | 1658 (44.4%) | 2 151 693 |

| Cervical screening | ||||||

| No | 1471 (84.7%) | 2 256 700 | 533 (26.7%) | 649 545 | 2004 (53.7%) | 2 906 245 |

| Yes | 266 (15.3%) | 403 308 | 1464 (73.3%) | 1 493 202 | 1730 (46.3%) | 1 896 511 |

| Total | 1737 (100.0%) | 2 660 008 | 1997 (100.0%) | 2 142 747 | 3734 (100.0%) | 4 802 755 |

Table 2 shows the distribution of general characteristics by participation in cervical cancer screening and age group. In the 15–29 and 30–39 groups, age was associated with participation (p<0.001). For those aged 15–39, 51.1% of those participating in cervical cancer screening had more than 12 years of education. The participation rate was highest for those with a total household income in the third quartile, 45.3% for those aged 15–39. Ex-smoker and current smoker status were associated with participating in screening (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Distribution of participation for cervical cancer screening among young Korean women by age group

| Age groups |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–29 |

30–39 |

Total |

|||||||||||||

| No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

||||||||||

| Cervical cancer screening | e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

p Value | e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

p Value | e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

e% (e mean) |

e%SE (eSE) |

p Value |

| Age | (21.5) | (0.1) | (26.6) | (0.2) | <0.001 | (34.1) | (0.1) | (34.8) | (0.1) | <0.001 | (24.3) | (0.2) | (33.1) | (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Menarche age | (13.6) | (0.3) | (13.6) | (0.2) | 0.849 | (13.7) | (0.1) | (13.7) | (0.1) | 0.710 | (13.6) | (0.2) | (13.7) | (0.1) | 0.764 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) | (21.4) | (0.1) | (21.6) | (0.3) | <0.001 | (22.6) | (0.2) | (22.6) | (0.1) | 0.902 | (21.7) | (0.1) | (22.4) | (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Education levels | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| <6 | 96.6 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 57.7 | 18.4 | 42.3 | 18.4 | 89.4 | 5.1 | 10.6 | 5.1 | |||

| 6–9 | 97.5 | 1.0 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 65.7 | 10.4 | 34.3 | 10.4 | 95.4 | 1.2 | 4.6 | 1.2 | |||

| 10–12 | 83.2 | 1.7 | 43.0 | 1.7 | 27.9 | 2.1 | 72.1 | 2.1 | 57.6 | 1.7 | 42.4 | 1.7 | |||

| >12 | 76.7 | 1.6 | 52.7 | 1.6 | 26.6 | 1.7 | 26.6 | 1.7 | 48.9 | 1.5 | 51.1 | 1.5 | |||

| Total household income | 0.062 | 0.018 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | 91.8 | 2.8 | 8.2 | 2.8 | 44.7 | 6.2 | 55.3 | 6.2 | 77.1 | 3.2 | 22.9 | 3.2 | |||

| 2Q | 85.0 | 1.9 | 15.0 | 1.9 | 30.8 | 2.3 | 69.2 | 2.3 | 59.3 | 1.9 | 40.7 | 1.9 | |||

| 3Q | 81.7 | 2.0 | 18.3 | 2.0 | 27.7 | 2.2 | 72.3 | 2.2 | 54.7 | 1.9 | 45.3 | 1.9 | |||

| 4Q (highest) | 84.4 | 1.7 | 15.6 | 1.7 | 28.0 | 2.4 | 72.0 | 2.4 | 61.6 | 1.8 | 38.4 | 1.8 | |||

| Smoking status | <0.001 | 0.016 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| Never smoker | 88.2 | 0.9 | 11.8 | 0.9 | 29.8 | 1.5 | 70.2 | 1.5 | 62.5 | 1.1 | 37.5 | 1.1 | |||

| Ex-smoker | 58.6 | 5.2 | 41.4 | 5.2 | 24.9 | 3.8 | 75.1 | 3.8 | 41.8 | 3.4 | 58.2 | 3.4 | |||

| Current smoker | 75.5 | 4.3 | 24.5 | 4.3 | 40.8 | 4.5 | 59.2 | 4.5 | 59.8 | 3.4 | 40.2 | 3.4 | |||

| Alcohol consumption (per month) | 0.023 | 0.038 | <0.001 | ||||||||||||

| 1 or less | 86.9 | 1.3 | 13.1 | 1.3 | 32.9 | 2.0 | 67.1 | 2.0 | 63.6 | 1.4 | 36.4 | 1.4 | |||

| 1 or more | 82.3 | 1.5 | 17.7 | 1.5 | 27.5 | 1.8 | 72.5 | 1.8 | 56.9 | 1.4 | 43.1 | 1.4 | |||

| Current job | 0.035 | 0.052 | 0.524 | ||||||||||||

| No | 86.8 | 1.3 | 13.2 | 1.3 | 28.1 | 1.8 | 71.9 | 1.8 | 61.0 | 1.4 | 39.0 | 1.4 | |||

| Yes | 82.4 | 1.5 | 17.6 | 1.5 | 33.0 | 1.9 | 67.0 | 1.9 | 59.9 | 1.5 | 40.1 | 1.5 | |||

e%, estimated per cent with weights; eSE, estimated SE with weight.

The factors associated with participation in screening by simple survey logistic regression are presented in table 3. Age (per year), education level, total house income, smoking status, drinking frequency (per month) and job status were associated with participation in the simple survey logistic analysis (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Factors associated with participation in cervical cancer screening by simple logistic regression analysis

| Age groups |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–29 |

30–39 |

Total |

|||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | ||

| Age | (per 1 year) | 1.463 | (1.388 to 1.542) | 1.096 | (1.054 to 1.140) | 1.270 | (1.249 to 1.293) |

| 15–29 | Reference | ||||||

| 30–39 | 12.861 | (10.582 to 15.630) | |||||

| Menarche age (per 1 year) | 1.017 | (0.988 to 1.048) | 1.028 | (0.965 to 1.096) | 1.042 | (0.927 to 1.172) | |

| Body mass index (per kg/m²) | 1.015 | (0.974 to 1.058) | 0.998 | (0.963 to 1.034) | 1.054 | (1.030 to 1.077) | |

| Education levels | |||||||

| <6 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 6–9 | 0.749 | (0.118 to 4.746) | 0.711 | (0.116 to 4.361) | 0.404 | (0.121 to 1.353) | |

| 10–12 | 5.818 | (1.128 to 30.004) | 3.522 | (0.778 to 15.940) | 6.210 | (2.128 to 18.124) | |

| >12 | 8.735 | (1.686 to 45.262) | 3.754 | (0.854 to 16.497) | 8.824 | (3.032 to 25.684) | |

| Total household income | |||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 2Q | 1.987 | (0.890 to 4.436) | 1.817 | (1.053 to 3.138) | 2.306 | (1.565 to 3.399) | |

| 3Q | 2.516 | (1.152 to 5.495) | 2.108 | (1.237 to 3.593) | 2.779 | (1.865 to 4.143) | |

| 4Q (highest) | 2.090 | (0.958 to 4.560) | 2.081 | (1.214 to 3.567) | 2.091 | (1.416 to 3.087) | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Ex-smoker | 4.903 | (3.064 to 7.845) | 1.284 | (0.833 to 1.980) | 2.242 | (1.680 to 2.992) | |

| Current smoker | 2.530 | (1.616 to 3.960) | 0.625 | (0.442 to 0.885) | 1.097 | (0.844 to 1.426) | |

| Alcohol consumption (per month) | |||||||

| 1 or less | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 1 or more | 1.421 | (1.048 to 1.925) | 1.296 | (1.015 to 1.655) | 1.324 | (1.140 to 1.537) | |

| Current job | |||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Yes | 1.403 | (1.024 to 1.922) | 0.793 | (0.627 to 1.001) | 1.050 | (0.903 to 1.222) | |

Table 4 shows the results of the multiple survey logistic regression analysis, including the adjusted OR and 95% CI after adjustment for age, menarche age, BMI, education, total household income, smoking, alcohol consumption and job status. The ORs for age (per year) among those aged 15–29 and 30–39 were 1.511 (95% CI 1.41 to 1.62) and 1.096 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.1), respectively. Those with total household incomes in the third and fourth quartiles (OR 1.96, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.45 and OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.19 to 3.83, respectively) in the 30–39 age group were more likely to participate in screening. Job status was also associated with participation in screening in both the 15–29 and 30–39 age groups (p<0.05).

Table 4.

Factors associated with participation in cervical cancer screening by multiple logistic regression analysis

| Age groups |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–29 |

30–39 |

Total |

||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.511 | (1.411 to 1.617) | 1.096 | (1.049 to 1.144) | ||

| 15–29 | Reference | |||||

| 30–39 | 10.823 | (8.851 to 13.234) | ||||

| Menarche age | 1.011 | (0.994 to 1.028) | 1.034 | (0.963 to 1.111) | 1.009 | (0.995 to 1.024) |

| Body mass index (per 1 kg/m²) | 0.974 | (0.929 to 1.020) | 1.002 | (0.964 to 1.042) | 1.011 | (0.983 to 1.041) |

| Education levels | ||||||

| <6 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 6–9 | 0.424 | (0.065 to 2.768) | 0.699 | (0.125 to 3.903) | 0.542 | (0.170 to 1.729) |

| 10–12 | 0.551 | (0.117 to 2.589) | 3.397 | (0.816 to 14.135) | 4.055 | (1.456 to 11.292) |

| >12 | 0.377 | (0.077 to 1.850) | 3.646 | (0.883 to 15.057) | 5.154 | (1.855 to 14.317) |

| Total household income | ||||||

| 1Q (lowest) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 2Q | 1.227 | (0.494 to 3.048) | 1.765 | (0.992 to 3.139) | 1.803 | (1.118 to 2.906) |

| 3Q | 1.375 | (0.551 to 3.433) | 1.958 | (1.111 to 3.451) | 2.010 | (1.231 to 3.283) |

| 4Q (highest) | 1.293 | (0.530 to 3.157) | 2.135 | (1.190 to 3.830) | 1.929 | (1.186 to 3.138) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Never smoker | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Ex-smoker | 2.894 | (1.621 to 5.168) | 1.205 | (0.761 to 1.907) | 2.253 | (1.507 to 3.369) |

| Current smoker | 1.741 | (0.966 to 3.139) | 0.707 | (0.478 to 1.046) | 1.329 | (0.909 to 1.943) |

| Alcohol consumption (per month) | ||||||

| 1 or less | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| 1 or more | 0.946 | (0.656 to 1.363) | 1.235 | (0.938 to 1.625) | 1.045 | (0.839 to 1.301) |

| Current job | ||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Yes | 0.534 | (0.349 to 0.816) | 0.554 | (0.425 to 0.722) | 0.649 | (0.532 to 0.793) |

Discussion

Data from KNHANES V showed that the participation rate in screening for cervical cancer was especially low (46%) in women aged 15–39 years. This result was associated with demographic factors, such as age, socioeconomic status (education, income, and occupation), and health behavioural factors (smoking, drinking frequency). An additional analysis showed that the participation rate in screening for cervical cancer among Korean women aged 15–80 was 58.6%. This is extremely low compared with those observed in other developed countries; for example, the screening rate is approximately 82.9% in the USA,21 80% in the UK22 and 70% in Finland.23 Other studies from Asia suggest that participation in screening for cervical cancer is low (42.1% in Japan, 2013, 52.9% in Taiwan, 2006).24 25 The low rate of cervical cancer among young women may explain the overall low rate of participation in the cervical cancer screening programme.

Why is the rate of screening for cervical cancer lower in Asia? For Asian women, there are several barriers, such as knowledge about screening; emotional barriers, such as fear/social stigma; social barriers, such as support of family and friends; and cultural barriers, such as taboos regarding discussing sexually related topics.26 Employment status was also associated with participation in screening for cervical cancer. Women who were employed had lower screening participation than those without jobs. In Asian cultures, it can be difficult to attend a cancer screening programme during working hours because companies do not provide leave for such appointments. Thus, to increase screening in Asian countries, a comprehensive approach to reduce these barriers is needed.

In Korea, national clinical guidelines recommend the frequency of cervical cancer screening.4 Since the introduction of screening for cervical cancer, opportunistic and systematic screening have become widespread.5 Currently, there are two organised cancer screening programmes in Korea: the NCSP, whose target populations include MAP receivers and NHI beneficiaries with income in the lower 50%, and the NHICSP, which is offered to NHI beneficiaries with income in the upper 50%.4 5 These two programmes provide screening free of charge to all Korean women aged 20–70 every 2 years. HPV-DNA testing programmes are also in place, such as Hybrid Capture 2 (HC2), the DNA Chip test, and HPV Genotyping (COBAS). If the result of a Pap smear shows more than atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US), the patient can apply for an HPV-DNA test if she is insured by NHI.4

In the present study, participation in cervical cancer screening was positively associated with age (per year) in both age groups. However, the impact of age differed in the two groups. Women older than 30 are eligible for the cervical cancer screening covered by the NHICSP. Thus, the OR (per 1 year) for participation in screening was higher for the 30–39 age group than for the 15–29 group (OR 1.511, 95% CI 1.411–1.617 vs OR 1.096, 95% CI 1.049 to 1.144). Women eligible for organised cancer screening programmes are likely to participate in screening for cervical cancer; therefore, the absolute participation rate in screening was higher among those aged 30–39 than among those aged 15–29. Indeed, the participation rate was up to 70% in females aged 30 or more. Whether age over 30 was important was assessed by considering the effect of age per year. The ORs for women aged 30 or older (reference: aged 15–29) was 10.823 (95% CI 8.851 to 13.234). However, in women aged 15–29, increasing age may be associated with a greater likelihood of obstetric and gynaecological problems and thus a higher likelihood of visiting a clinic, where they would likely undergo cancer screening. This might be the reason for the positive association between increasing age and participation in cervical cancer screening among women aged 15–29 years.

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) was related to lower participation in screening for cervical cancer in women aged 30–39 (for income levels, ORs were 1.95 with 3Q income and 2.13 with 4Q income) and aged 15–39 (for education, ORs were 4.055 with 10–12 years' schooling and 5.154 with 12 or more years' schooling). There are several possible reasons for this relationship.27–29 Low SES may influence health outcomes through a lack of knowledge about the health impact of lifestyle risk factors, behaviours or routine screening, and reduced access to healthcare due to financial, physical or social barriers to healthcare system access. Therefore, women of higher SES would be more likely to participate in screening. For those aged 30–39 of high SES, the likelihood of visiting a clinic for obstetrical or gynaecological problems, and therefore undergoing cervical cancer screening, increases with age. For women of lower SES, however, the absence of patient education and reduced access to care may mean that women aged 30–39 are less likely to visit a clinic for similar problems and therefore less likely to be screened for cervical cancer. To overcome these barriers, the Korean government provides organised cervical cancer screening programmes without cost to encourage participation by women of lower SES. The present study did not distinguish between organised and opportunistic participation among women aged 30–39. Therefore, the impact of organised cancer screening in this age group could not be determined. However, the impact of opportunistic cervical screening participation and SES-related disparities in opportunistic cervical cancer screening was implied by our study. Participation in cervical cancer screening among women aged 15–29 is entirely opportunistic in Korea. Total household income might have positively influenced participation in screening in the 15–29-year age group, but the relationship was not statistically significant. A study with a larger number of 15–29-year-old cervical cancer screening participants is needed to assess the significance of this trend.

Smoking status was associated with participation in screening for cervical cancer (ex-smoker: OR 2.253 vs current smoker: OR 1.329). Consistent with previous studies,30 31 we found that women who were 30–39 years old and current smokers were less likely to participate in screening. Although women are aware of the negative health outcomes associated with smoking, those who are unwilling or unable to stop smoking may be less likely to participate in health screening in general.30 31 However, they need to understand the risk factors for cervical cancer in women who smoke to encourage them to use screening services. Among those aged 15–29, ex-smokers tended to have higher participation in screening than current smokers and non-smokers. This may be because the ex-smoker has decided to adopt a healthier lifestyle.32 The ex-smoker visits the hospital relatively frequently if interested in personal healthcare, so participation in cervical cancer screening through consultation may also be higher than for others. However, several studies conducted in the USA, Italy and Puerto Rico have reported that cervical cancer screening is not associated with smoking status.32–34 A young current smoker may be a little less worried about the potential risk to her health or may have excessive confidence in her health.

Job status was also associated with participation in screening for cervical cancer in both age groups. Those who had a job had lower attendance behaviour in screening than those without jobs. Why is this so? There may be a cultural difference between Western and Asian countries. In Asian cultures, it can be difficult to attend a cancer screening programme during work, because companies do not provide leave for such things. Thus, to increase participation in cervical cancer screening, we must take into account screening opportunities for women with jobs.

There are several limitations to this study. First, because all of the information was derived from self-reported surveys, there may have been information bias, such as acquiescence or recall bias. To minimise these biases in screening for cervical cancer, the KNHANES was conducted by educated and well-trained interviewers. However, recall and acquiescence bias may have remained, resulting in misclassification. Another limitation was the lack of detailed information concerning risk factors (family history of cervical cancer or history of HPV testing). In addition, given the lack of access to clinical records, Pap smear results could not be confirmed. Also, other factors that were not taken into account in our study might have impacted healthcare utilisation, such as insurance status and type and urban/rural differences. There may also be selection bias because screening for cervical cancer is recommended after the age of 30.

However, our research has several strengths. First, the results are based on a large representative sample. Because a stratified multi-staged clustered probability design was used to select representative samples of non-institutionalised Koreans for KNHANES V, the possibility of selection bias was reduced.8 Second, predictors of screening for cervical cancer were estimated in a multi-dimensional structure, including both individual and environmental levels. Third, the age-standardised proportion of those participating in screening for cervical cancer was analysed to fit age effects.

Conclusions

Age and job status were associated with participation in screening for cervical cancer in women aged 15–29 and 30–39 years. In addition, there was an association between participation and high total household income in the 30–39 age group. To improve the participation rate in screening for cervical cancer, continuous efforts such as public campaigns and educational programmes for young women are needed. Finally, more aggressive age-based interventions and policies aimed at improving participation in screening, particularly in young working women, are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Research Fund of Seoul St Mary's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea.

Footnotes

Contributors: HKC and J-PM conceived and designed the study. Data were analysed by HKC and J-PM. Conception and design summary: SWB, S-JL, YSL, H-NL, KHL, DCP, CJK and SYH. Analysis and interpretation of data: HKC, J-PM, KHL, JSP and TCP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Research Fund of Seoul St Mary's hospital, The Catholic University of Korea.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The KNHANES data are depersonalised and publicly available. Ethics approval and consent to participate were not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All relevant materials are provided in the manuscript. Data access for the KNHANES V is available from http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R. , et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E359–86. 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Korea Central Cancer Registry National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2012 Ilsan: Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anttila A, Ronco G, Clifford G et al. Cervical cancer screening programmes and policies in 18 European countries. Br J Cancer 2004;91:935–41. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim Y, Jun JK, Choi KS et al. Overview of the National Cancer Screening Programme and the cancer screening status in Korea. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:725–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee YH, Choi KS, Lee HY et al. Current status of the National Cancer Screening Program for cervical cancer in Korea, 2009. J Gynecol Oncol 2012;23:16–21. 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.1.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown ML, Klabunde CN, Cronin KA et al. Challenges in meeting Healthy People 2020 objectives for cancer-related preventive services, National Health Interview Survey, 2008 and 2010. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:E29 10.5888/pcd11.130174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simou E, Maniadakis N, Pallis A et al. Factors associated with the use of Pap smear testing in Greece. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:1577–85. 10.1089/jwh.2009.1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myong JP, Shin JY, Kim SJ. Factors associated with participation in colorectal cancer screening in Korea: the Fourth Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV). Int J Colorectal Dis 2012;27:1061–9. 10.1007/s00384-012-1428-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SJ, Park WS. Identifying barriers to Papanicolaou smear screening in Korean women: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005. J Gynecol Oncol 2010;21:81–6. 10.3802/jgo.2010.21.2.81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitch MI, Greenberg M, Cava M et al. Exploring the barriers to cervical screening in an urban Canadian setting. Cancer Nurs 1998;21:441–9. 10.1097/00002820-199812000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holroyd E, Twinn SF, Shia AT. Chinese women's experiences and images of the Pap smear examination. Cancer Nurs 2001;24:68–75. 10.1097/00002820-200102000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbert A. The value of cervical screening to young women. Br J Cancer 2004;90:1108; author reply 9–10 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han CH, Cho HJ, Lee SJ et al. The increasing frequency of cervical cancer in Korean women under 35. Cancer Res Treat 2008;40:1–5. 10.4143/crt.2008.40.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan PG, Sung HY, Sawaya GF. Changes in cervical cancer incidence after three decades of screening US women less than 30 years old. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E et al. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet 2006;368:1706–28. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69479-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CJ, Kim BG, Kim SC et al. Sexual behavior of Korean young women: preliminary study for the introducing of HPV prophylactic vaccine. Korean J Gynecol Oncol 2007;18:209–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M, Chang HS, Park EC et al. Factors associated with participation of Korean women in cervical cancer screening examination by age group. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011;12:1457–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. http://knhanes.cdc.go.kr (accessed 28 Jun 2016).

- 19.Jeong H, Hong S, Heo Y et al. Vitamin D status and associated occupational factors in Korean wage workers: data from the 5th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES 2010-2012). Ann Occup Environ Med 2014;26:28 10.1186/s40557-014-0028-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JY, Lee DH. Factors associated with the use of gastric cancer screening services in Korea: the Fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008 (KNHANES IV). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2012;13:3773–9. 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross JS, Bradley EH, Busch SH. Use of health care services by lower-income and higher-income uninsured adults. JAMA 2006;295:2027–36. 10.1001/jama.295.17.2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda Y, Sobue T, Morimoto A et al. Evaluation of a free-coupon program for cervical cancer screening among the young: a nationally funded program conducted by a local government in Japan. J Epidemiol 2015;25:50–6. 10.2188/jea.JE20140080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virtanen A, Anttila A, Luostarinen T et al. Improving cervical cancer screening attendance in Finland. Int J Cancer 2015;136:E677–84. 10.1002/ijc.29176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka Y, Ueda Y, Kishida H et al. Trends in the cervical cancer screening rates in a city in Japan between the years of 2004 and 2013. Int J Clin Oncol 2015;20:1156–60. 10.1007/s10147-015-0842-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung SD, Pfeiffer S, Lin HC. Lower utilization of cervical cancer screening by nurses in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Prev Med 2011;53:82–4. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu M, Moritz S, Lorenzetti D et al. A systematic review of interventions to increase breast and cervical cancer screening uptake among Asian women. BMC Public Health 2012;12:413 10.1186/1471-2458-12-413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung HM, Lee JS, Lairson DR et al. The effect of national cancer screening on disparity reduction in cancer stage at diagnosis by income level. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0136036 10.1371/journal.pone.0136036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kwak MS, Park EC, Bang JY et al. [Factors associated with cancer screening participation, Korea]. J Prev Med Public Health 2005;38:473–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee M, Park EC, Chang HS et al. Socioeconomic disparity in cervical cancer screening among Korean women: 1998–2010. BMC Public Health 2013;13:553 10.1186/1471-2458-13-553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark MA, Rakowski W, Ehrich B. Breast and cervical cancer screening: associations with personal, spouse's, and combined smoking status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2000;9:513–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messina CR, Kabat GC, Lane DS. Perceptions of risk factors for breast cancer and attitudes toward mammography among women who are current, ex- and non-smokers. Women Health 2002;36:65–82. 10.1300/J013v36n03_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damiani G, Federico B, Basso D et al. Socioeconomic disparities in the uptake of breast and cervical cancer screening in Italy: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:99 10.1186/1471-2458-12-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rakowski W, Clark MA, Ehrich B. Smoking and cancer screening for women ages 42–75: associations in the 1990–1994 National Health Interview Surveys. Prev Med 1999;29:487–95. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortiz AP, Hebl S, Serrano R et al. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening in Puerto Rico. Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7:A58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]